Exhibition dates: 4th April – 2nd July 2023

Curators: Christine Barthe: Head of the Photography Heritage Department at the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac; Annabelle Lacour: Head of the Photography Collection at the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

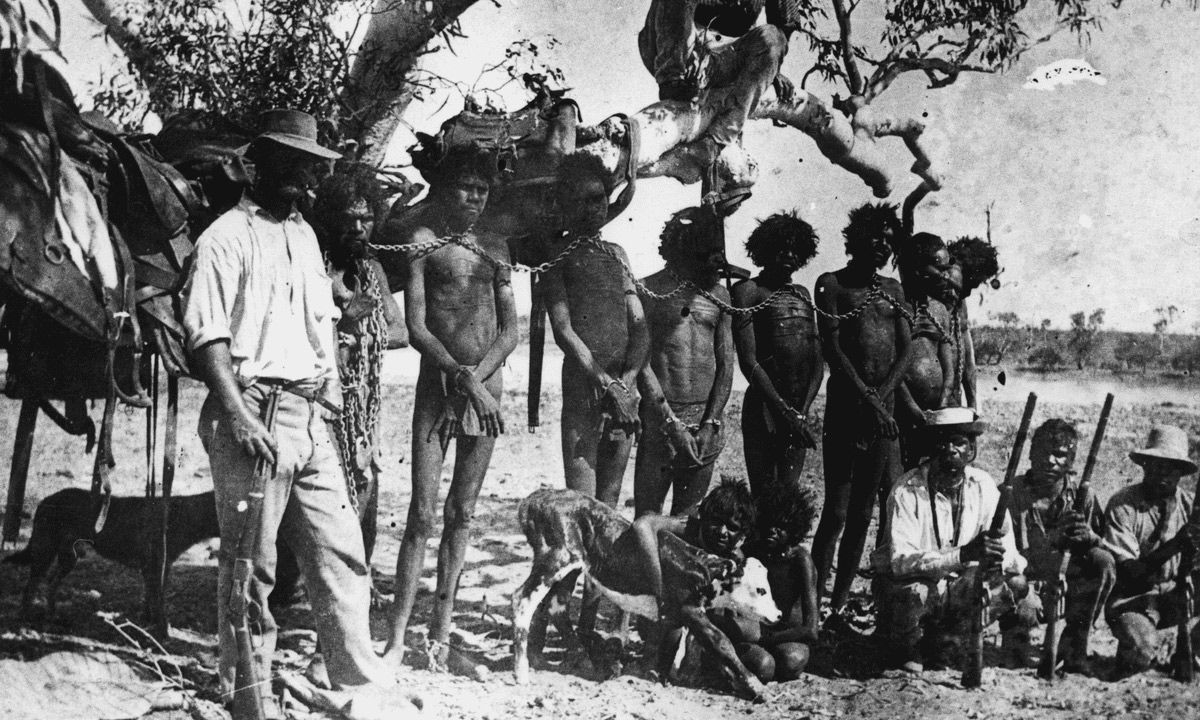

Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this posting contains images and names of people who may have since passed away.

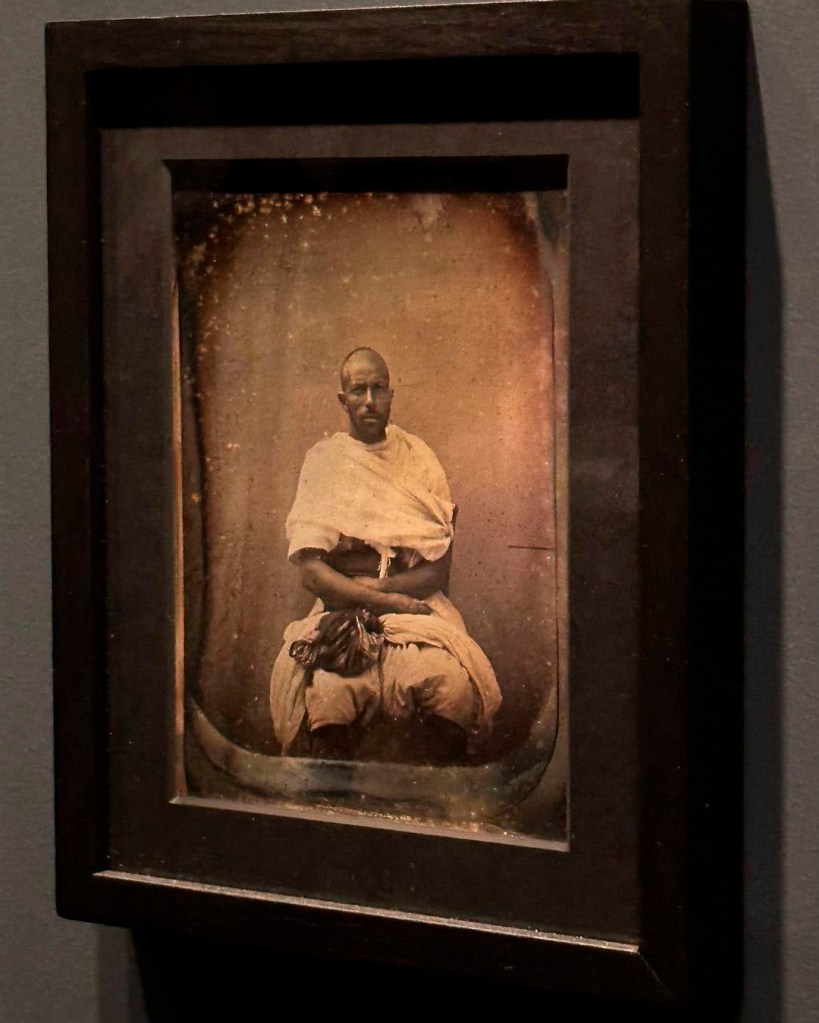

Unknown photographer

Portrait of a Persian Dignitary

Tehran, 1848

Daguerreotype

Photo: RMN – Grand Palais (Musée d’Orsay) Hervé Lewandowski

I wish we had tele-transportation so that I could go and see this incredible exhibition about the beginnings of photography practiced outside Europe.

It took me many hours to construct this posting. Placing the information into a logical order was an important consideration, matching the installation photographs with the exhibition texts and individual images so that the story makes sense. Finding country of origin and dates for the photographers was another issue. Further bibliographic information has been added from sources around the internet to fill out life stories and sometimes this information was difficult to find.

Congratulations to the curators for assembling a photographic tour de force in which “the production of these images is diverse and responds to different wishes, desires, and fits into various different contexts.” In other words what was the force majeure, the greater force, that directed the what, where, when, how, who and for whom of their production. Here, force is the operative word… for many of the foremost contexts are both anthropological and geographic (to record what people and places looked like) under the guise of European colonial conquest: to “capture” the spirit of the people and conquered lands under force of occupation.

More interesting are the photographs taken by photographers of their own people, for example different Indian “casts” taken by a Indian born photographer. How did they picture themselves using a European machine? In this context we must remember that the images were usually taken to fulfil a commercial brief, either taken for a rich patron or to be sold through the photographers studio to local and foreign clients.

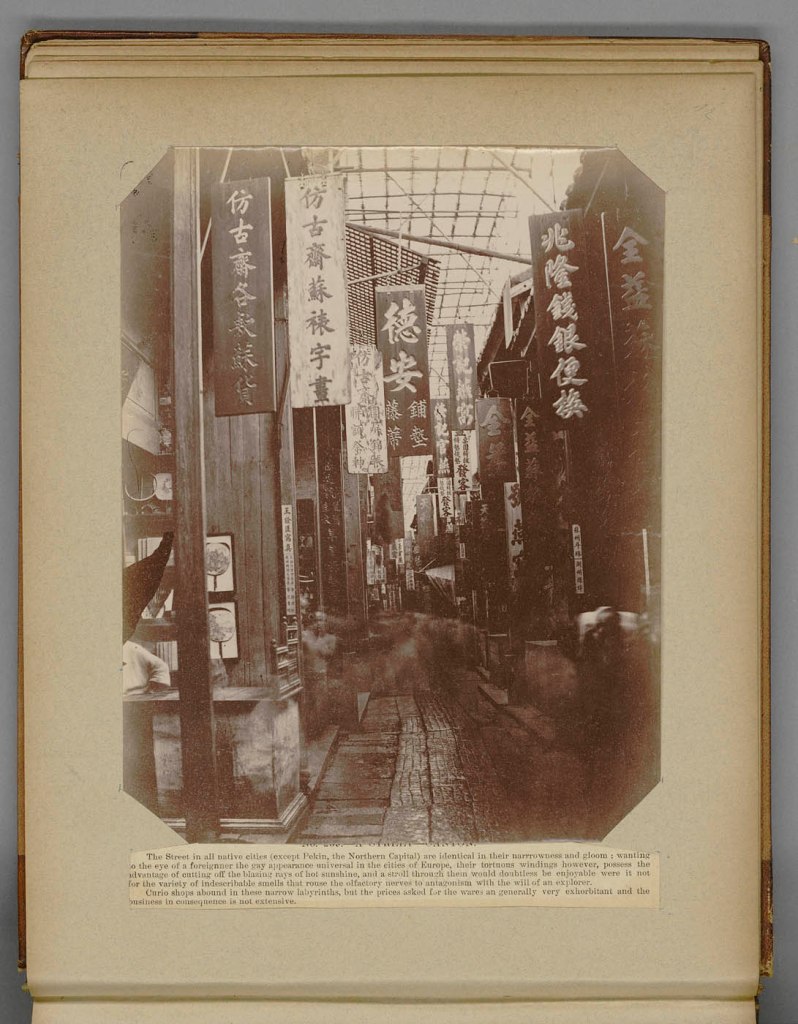

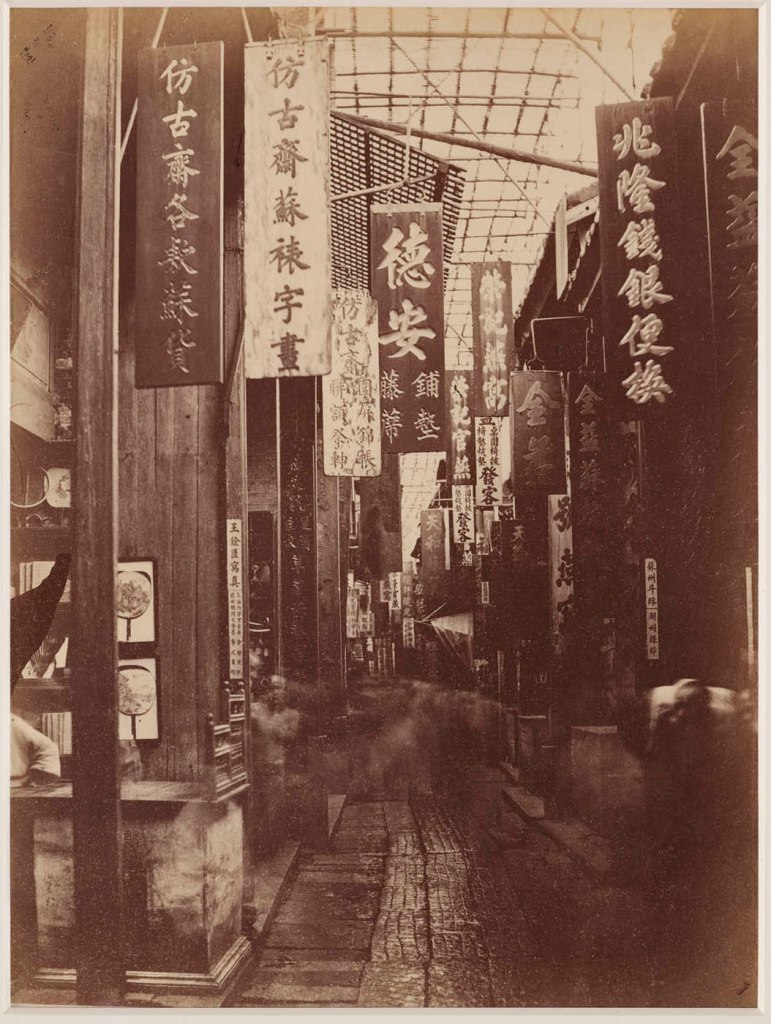

Predominantly using a Western pictorial language, sometimes these local photographers step outside the mould of making a portrait or casting a ‘type’ or recording a monument within the landscape by embodying within their art the aesthetics of their own cultural history. For example, “Lai Afong’s photographic compositions show the technical and aesthetic influence of traditional Chinese painting, known as guóhuà.” (Wikipedia) “In many regions, from Colombia to West Africa to Madagascar, and from Iran to Japan to India, photography was adopted and sometimes adapted to social uses and local cultures and in many places seems to satisfy the desire for self-representation and the construction of modern identities.” (Exhibition text)

Undoubtedly this was the exception rather than the rule – for the rule of the lawful image was usually Western in power and aesthetic. As the exhibition text notes, “The 19th century in Europe was characterised by a need to accumulate objects, knowledge and also territory. Through photography, landscapes became lands to be mapped and conquered, and their inhabitants subjects to be studied. In the scientific field, the natural history model influenced the use of photography. It contributed to the myth of virgin territories and was a tool in the growing geographical discipline, making claims of exhaustivity: see everything, photograph everything.” And one might add, own everything, both physically and visually (through the photographers and viewers gaze).

Thus the European photographer of the 19th century taxonomically ordered the world around him through a classification of the visual culture of the exotic. Anthropologically, “within the framework of a science then racial, and in a project typology inherited from natural history classification methods, photography is a tool that establishes visual categories that shape racial stereotypes.” This racial science was to have a lasting impact well into the 20th century through the now debunked theory of eugenics (which has no association with anthropology) – “the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations” (Galton) – influencing cultures around the world with devastating impact especially through the genocide of untermensch, or what were seen as racial subhumans, by the Nazi party in Germany in the 1930s-1940s.

What is undeniable is the inalienable presence of the sitter in these powerful portraits. This is William Lane in the here and now, with his strong face and sorrowful eyes. This is Botcudo “brought to France by a certain Mr. Porte and are going to stay in Paris for a few months.” This is his representation but also his spirit from the past, this impression all that is left of his life force today. But it is enough. We pay reverence to his life. This is a half-length portrait of a 77-year-old Japanese man… what did he do in his life, what journey led him to be present in front of the camera in February 1890, the learnt lines on his open face evidence of a hard life well lived. And these are Majeerteen Woman trapped in silver like ghosts in a machine, a movement of mutable energy through time and space that still has me engaging with their life even today. Bless them all.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Among the 101 photographers on show, 52 are Westerners and 49 are indigenous. This near-parity was made possible by the rise, over the last decade, of acquisitions of works by artists from the four continents.”

Quotation by curator Christine Barthe, head of the heritage unit at the Quai Branly’s photographic collection and co-curator of the exhibition with Anabelle Lacour, head of the photographic collection

Installation views of the exhibition Photographs. An Early Album of the World (1842-1911) at the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris showing in the two bottom images the section ‘Daguerreotypes for anthropology’ and in the bottom image the daguerreotypes of Henri Jacquart (French, 1809 – died after 1873) from September 1851 (below)

Many places in the world became accessible through photography as soon as it was invented in 1839. From the 1840s, darkrooms were taken on official expedition ships and crossed the borders of Europe. From Mexico to Gabon, the camera served the taste of the time for archaeological and geographical description and curiosity about the models encountered. In the second half of the 19th century, photography was used to examine all areas of the globe. This thirst for images was notably fuelled by the European colonial conquest.

Starting from the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac’s photograph collection, completed by exceptional loans from public and private collections, the exhibition considers the routes and the dissemination of photography outside Europe in the 19th century. Through a selection of photographs produced between 1842 and 1911 in Asia, Africa, Oceania and the Americas, it aims to understand better the development and the different appropriations of the medium locally by bringing to light less well-known photographs, patrons, phenomena and forms of photography in different parts of the world. An attempt to rebalance the history of photography, too often centred on Europe and the United States.

This exhibition is an adaptation of the exhibition Photographs. 1842-1896: An Early Album of the World designed by the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac and presented at the Louvre Abu Dhabi from 25 April to 13 July 2019.

Text from the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac website

There was a time without photography, and there were places without cameras. Even if it is hard to imagine nowadays, it was not so long ago. Since its invention in 1839, photography has extended its reach at varying paces into all the visible spaces and every corner of the globe: starting in familiar places, spreading to nearby regions and neighbouring countries, and finally making it way into more far-flung lands as well. From the most extraordinary scenes to the most trivial, from breathtaking scenery to the food on our plates, nothing is too intimate or too grandiose to escape our desire to take a picture of it.

But how did it all start? How did photography spread, contributing to our view of the world? Who are the players who make this “photo album of the world”?

Since the 1840s, photography has accompanied countless scientific and military expeditions and trips. It was part of the usual conquest of the world, in the context of colonial expansion by the European powers, which intensified in the second half of the 19th century. As a tool to describe landscape and map territories, it contributed to the knowledge and control of Indigenous populations. Europe did not have a monopoly over this modern technology, however. Photography travelled and was transformed. In many regions, from Mexico and Colombia to Sierra Leone and Madagascar, Iran, Japan and India, it was adopted and sometimes adapted to social practices and local cultures, to create, control and conserve an image of the self and one’s environment.

The exhibition revisits some of this early histories of photography outside of Europe.

Text from the exhibition

Henri Jacquart (French, 1809 – died after 1873)

Mohamed ben Said (installation view)

Paris, France, 1851

Daguerreotype

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

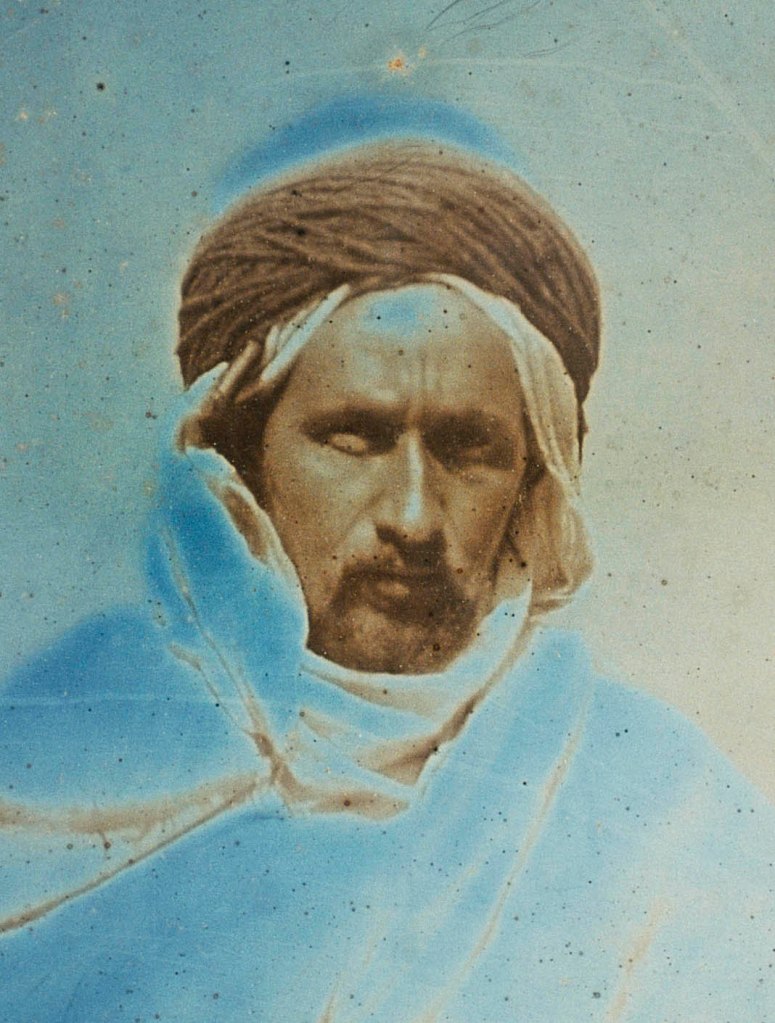

Henri Jacquart (French, 1809 – died after 1873)

Ibrahim Nascer, mozabite (installation view)

Paris, France, September 1851

Daguerreotype

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Exhibition introduction

There was a time without photography and places without a camera. Even if it is difficult to imagine it today, this period is not so far away.

Since the announcement of its invention in 1839, photography has more or less quickly invaded all visible spaces, penetrated all places on the scale of the globe: familiar places, nearby regions, then neighbouring countries, also the most distant. From the most extraordinary to the most trivial, from the sublime landscape to the content of our plates, nothing was too intimate or too grandiose to escape the desire to create its image.

How did it all start? How did photography come about? propagated, participating in the global geographical imagination? Who are the actors who make up this “world album”?

Since the 1840s, photography has accompanied the countless voyages and scientific and military expeditions. It participates in the visual conquest planetary, in the context of the colonial expansion of the European powers which accelerated in the second half of the 19th century. Description tool landscapes, territorial mapping, it supported the knowledge and population control. But Europe did not have a monopoly on this modern technology. Photography travels, transforms, takes root. In many regions, Mexico, Colombia, West Africa in Madagascar, from Iran to Japan via India, it has been adopted and sometimes adapted to social uses and local cultures to build, control and maintain an image of oneself and one’s environment.

This exhibition proposes to return to some of these stories from the beginnings of photography practiced outside Europe.

First appearances

The first technique that was widely used in the early days photography, between the 1840s and 1850s, takes its name “daguerreotype” of its inventor Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre. It’s about of a copper plate coated with silver and made sensitive to light. Relatively expensive to manufacture and requiring learning, this technique was widely used to produce portraits. The long exposure time made it difficult to apply it to the landscape. These images are unique because formed directly on the silver plate, they cannot therefore give rise to several tests. The difficulty of their realisation as well as their cost explain their rarity today. European and American practice in its very beginnings, the daguerreotype quickly exported around the world. new technique modifying the relationship to its own image, the daguerreotype is also used as a tool of scientific description. Practiced by travellers and traveling photographers, it was also adopted very early in many photographic studios of major world cities, such as Mexico City, Bogotá and Lima. In Tehran, the daguerreotype is practiced at the court of the Shah of Persia from 1845.

Daguerreotypes for anthropology

If photography is quickly adopted by travellers and offers a new vision of the real world, it also serves a new discipline: anthropology. In France, the first scientific applications of photography to this burgeoning field are experienced in the years 1840-1850. Within the framework of a science then racial, and in a project typology inherited from natural history classification methods, photography is a tool that establishes visual categories, that shape racial stereotypes. Daguerreotypes made on demand from the anthropology laboratory of the National Museum of Natural History show the importance attached by scientists to skulls, casts and human skeletons, central in a discipline marked by the medicine and comparatism. Produced by professionals like Louis-Auguste Bisson, or by employees of the Museum like Henri Jacquart, these examples testify of an objectification of bodies that photography reinforces. These daguerreotypes are produced or collected by the institution in the same way as the portraits of living people.

Text from the exhibition

Henri Jacquart (French, 1809 – died after 1873)

Ali ben Mohamed, 29 ans, Arab from the plain

September 1851

Daguerreotype

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Henri Jacquart (French, 1809 – died after 1873)

Ali ben Mohamed, 29 ans, Arab from the plain (detail)

September 1851

Daguerreotype

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Twenty years after the conquest of Algeria, the Arab horsemen have stopped fighting, and are but the shadows of those who for years thwarted the French army. They came to Paris for a show set up by the Museum, Children of the Desert, a fantasia on the Champ de Mars in June, 1851. They too are photographed, and casts of their bodies taken for science – but as popular artists, these horsemen leave their names under their portraits and are paid to pose.

Catherine Darley. “Ghosts (1) – Shadows,” on the Poemas del río Wang blog 10/08/2012 [Online] Cited 07/05/2023

Installation views of the exhibition Photographs. An Early Album of the World (1842-1911) at the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris showing in the bottom image the section ‘Recreated worlds: photo studios’ (below)

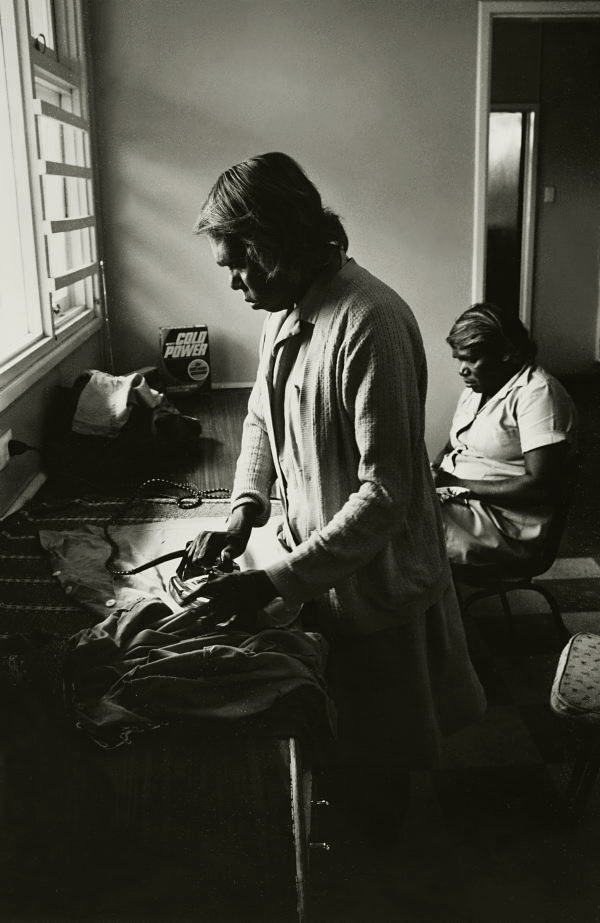

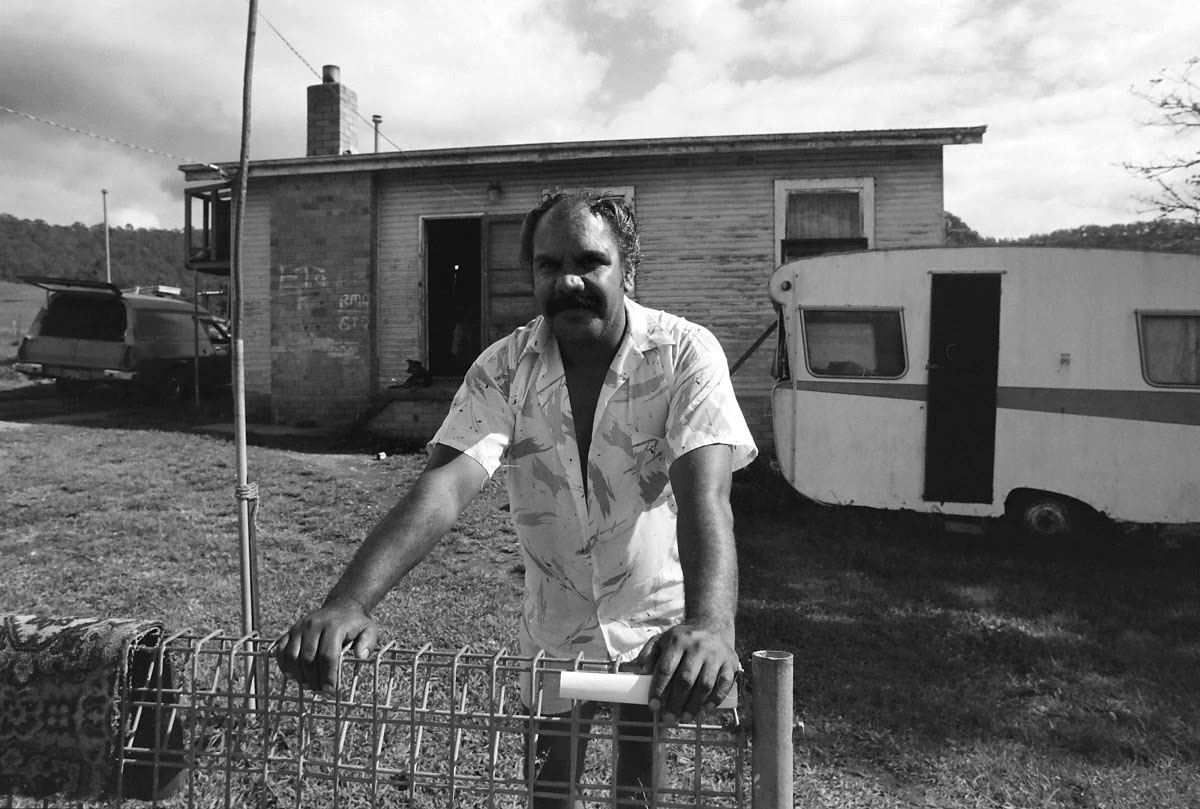

Recreated worlds: photo studios

In the second half of the 19th century, travel by land and sea developed considerably. European colonial expansion was one of the drivers behind the rise in global photographic coverage, not only did cameras and photographers travel, but so did their models. Members of the Indigenous elites made regular diplomatic trips or came to Europe to study. At the major colonial world’s fairs between 1870 and the early 20th century, groups were brought to European cities to be exhibited.

From the 1860s onwards, a great number of photo studios were set up in major cities. Those involved in this new commercial practice adapted to demand from a tourist clientele in search of exoticism, and sets and accessories were used to recreate artificial worlds. These widely distributed images with simplistic, sometimes demeaning captions, transmitted and perpetuated stereotypes. Photos with the frame centred on the face were often taken to respond to the need for description expressed in the field of physical anthropology. But studio decors also attracted a local clientele keen to create souvenirs with their loved ones.

Looking at these portraits, many questions remain today: Who are these individuals? What can we find out about their interactions with the photographer and their participation when being photographed?

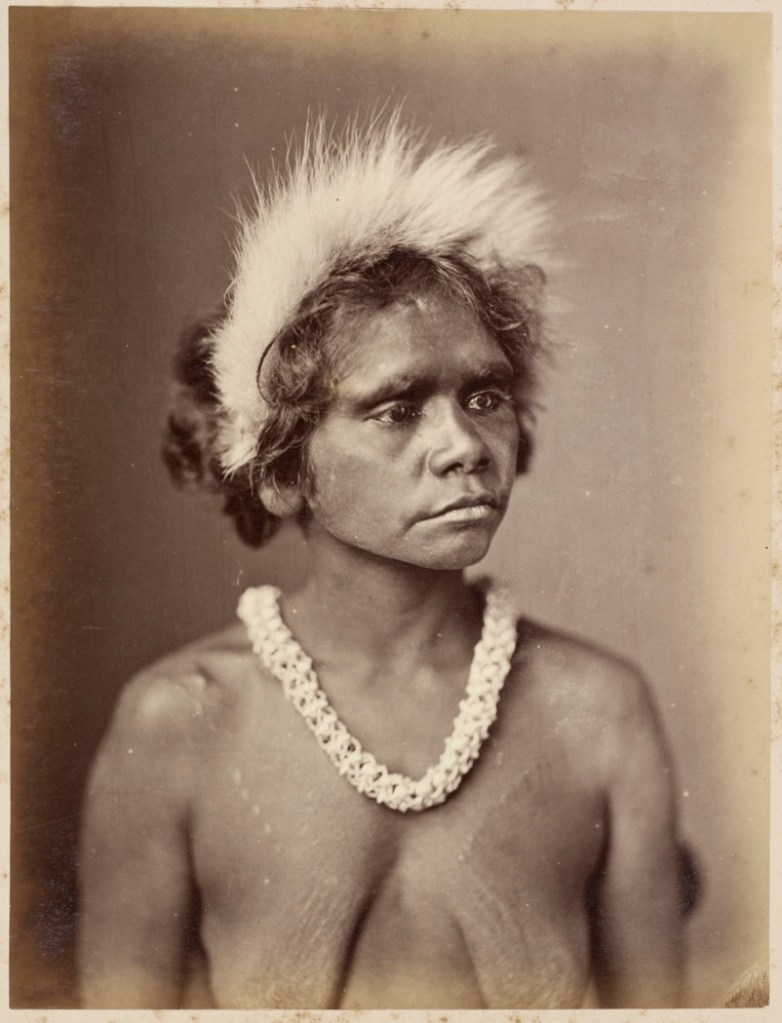

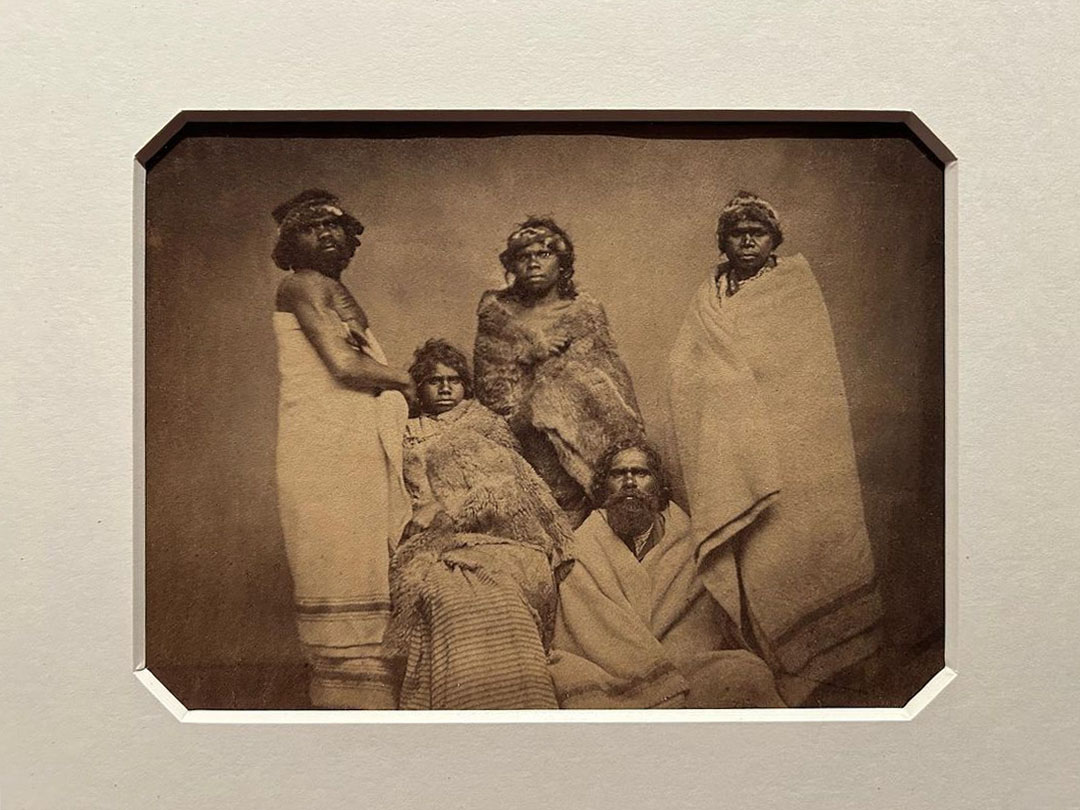

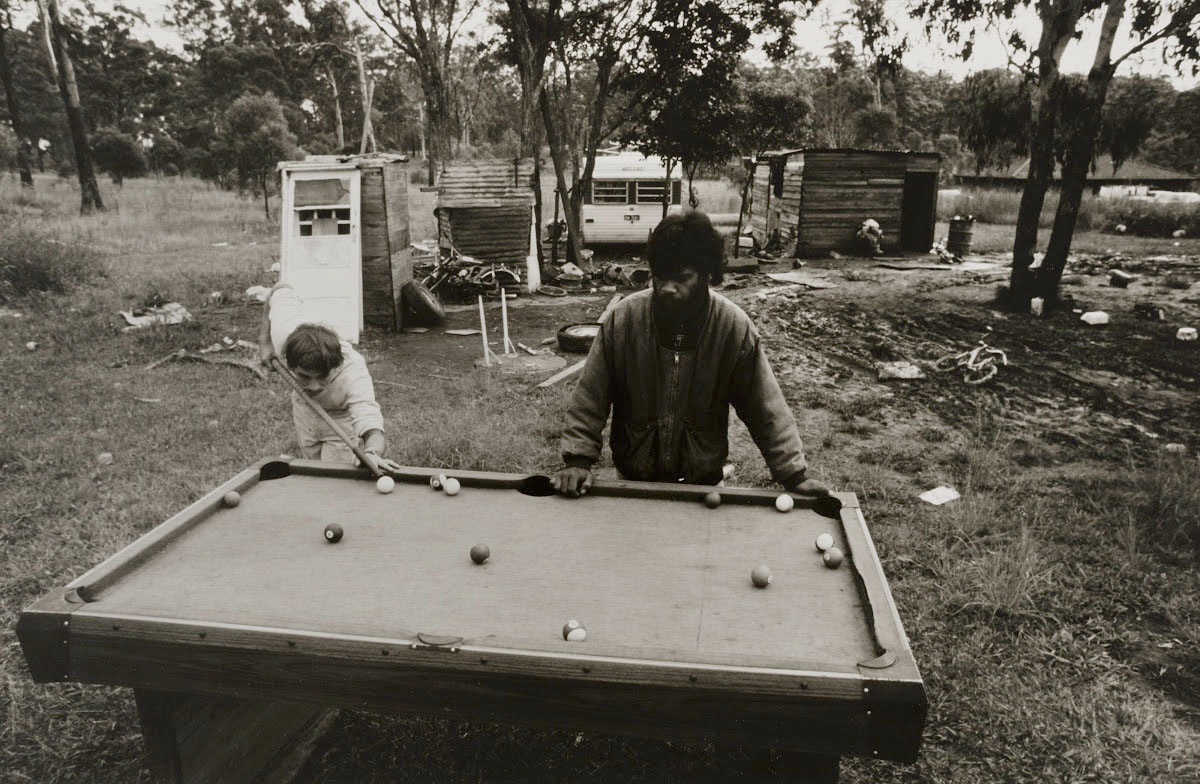

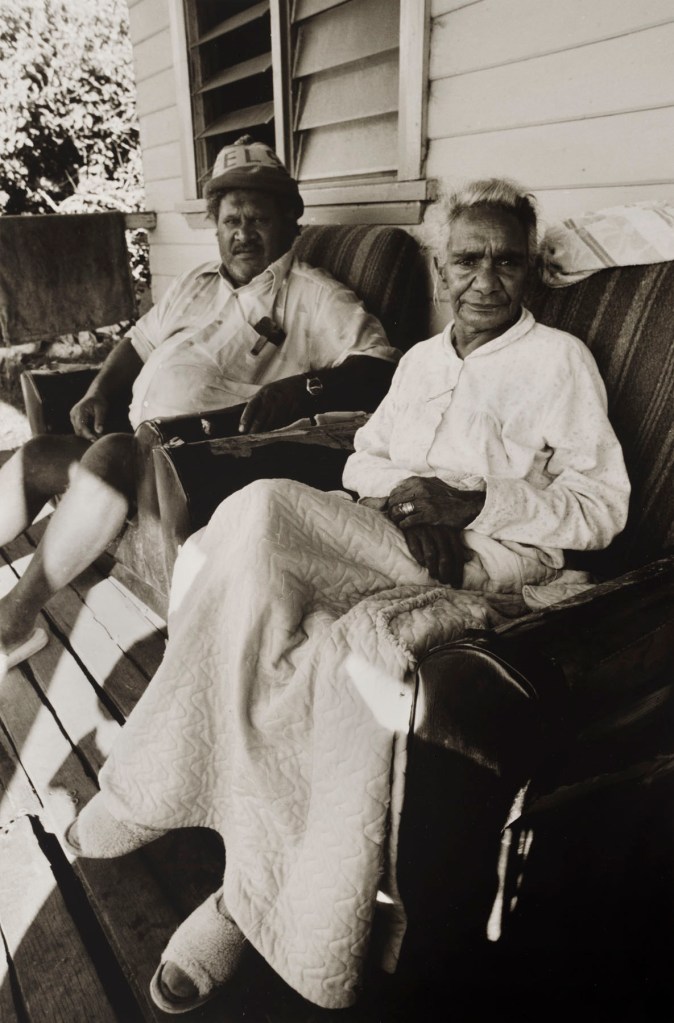

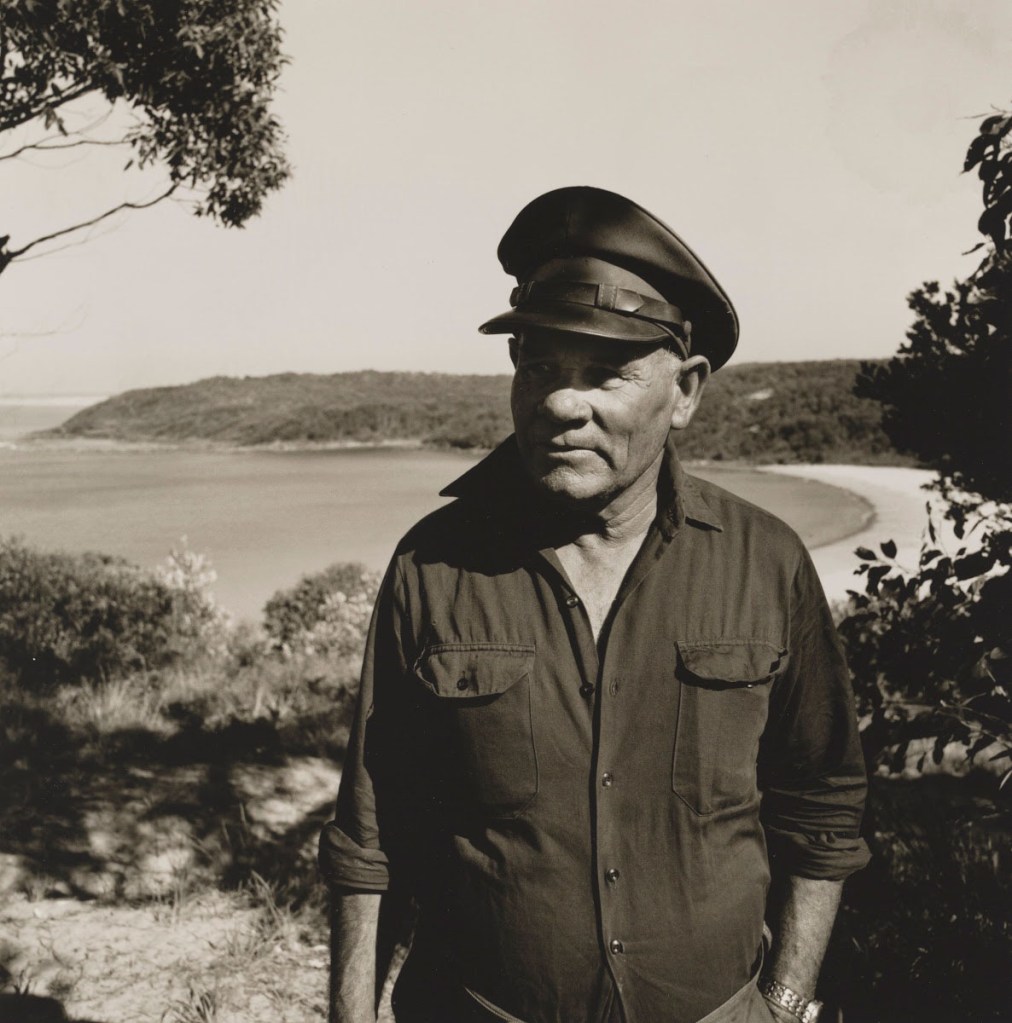

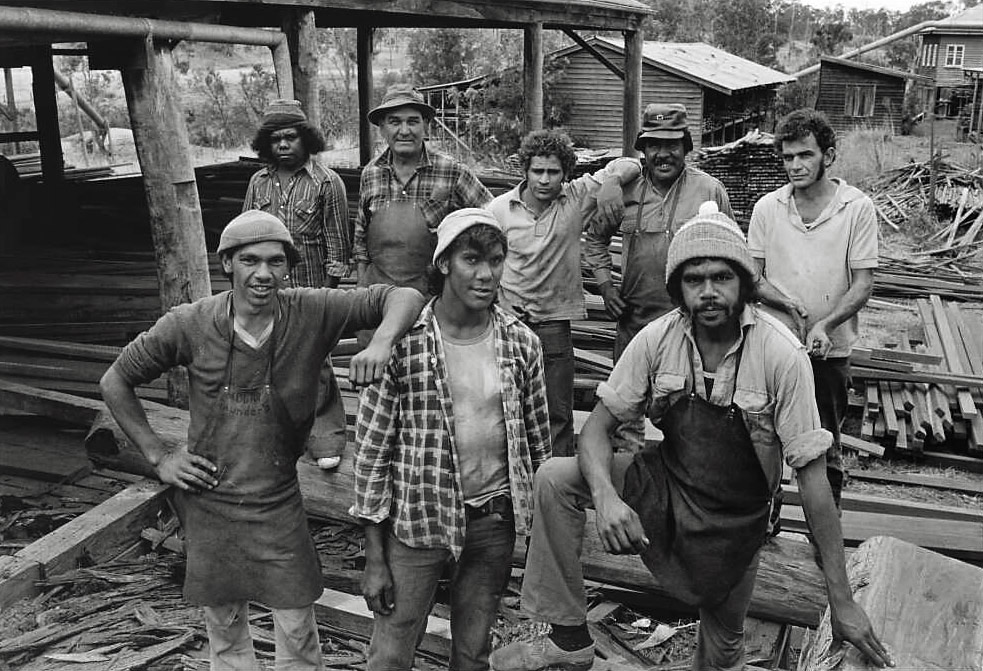

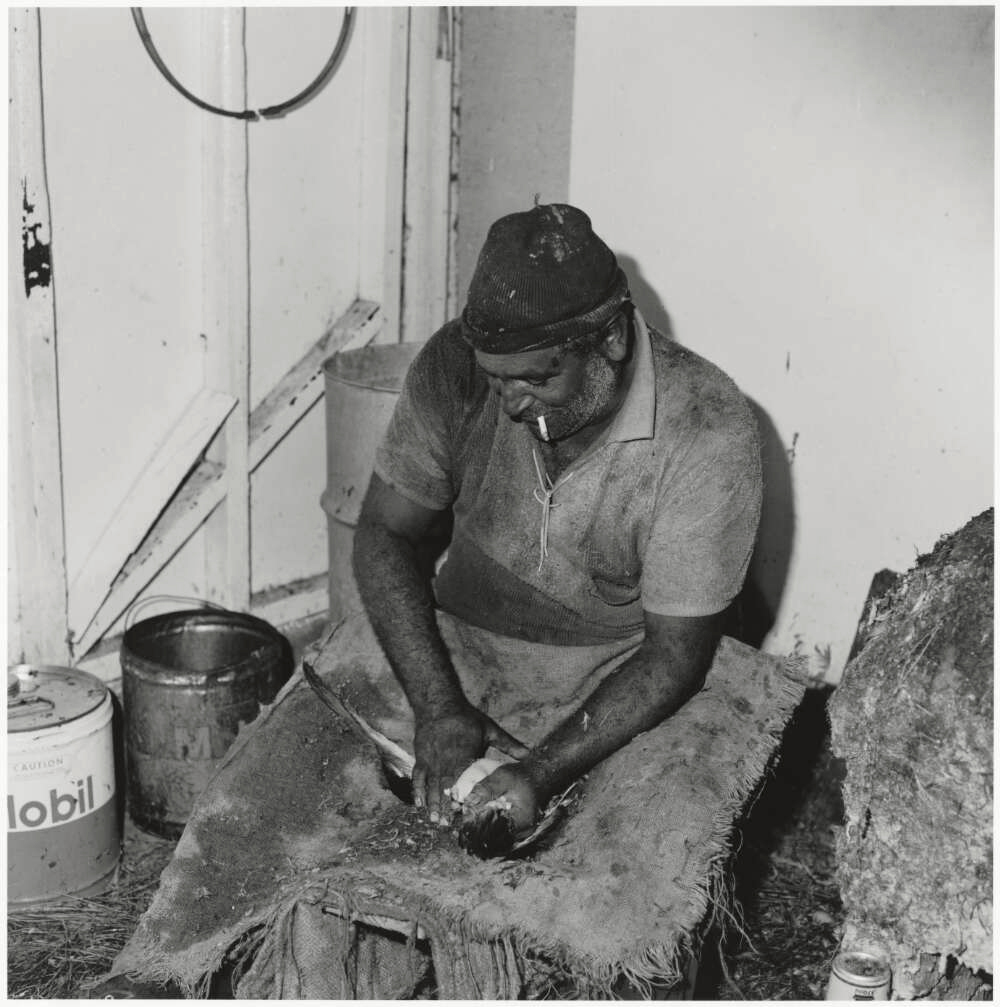

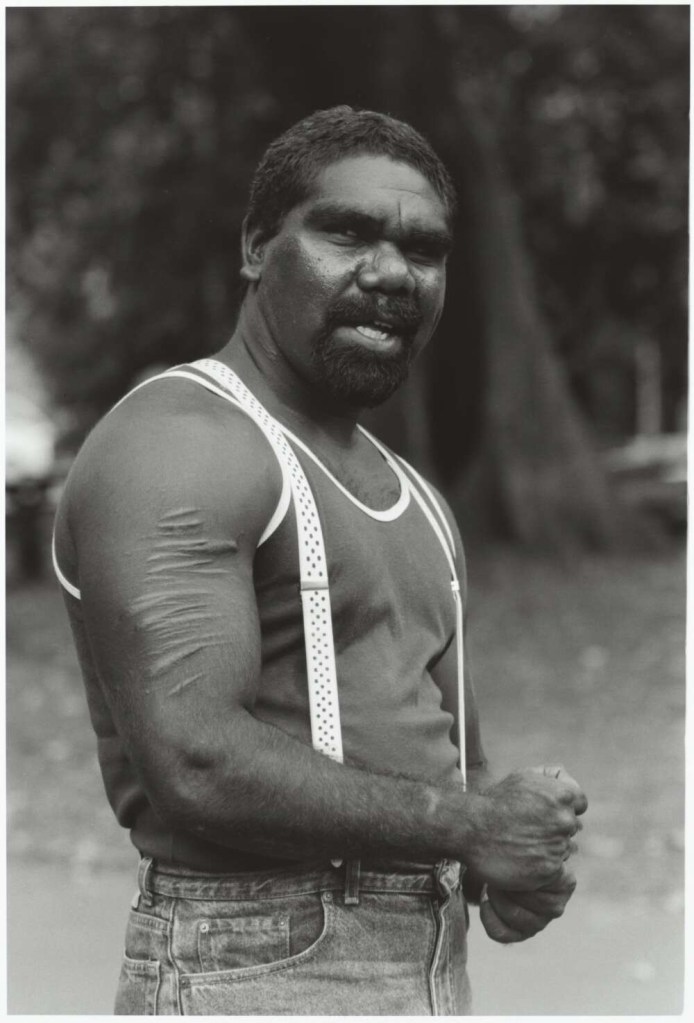

Portraits of Aboriginal Australians

The aboriginal populations were privileged subjects of the first commercial photographers in Australia. Produced in the studio, these portraits obey 19th century racialist scientific interests; they are designed to document what was then considered to be an endangered population. German photographer John William Lindt, based in Grafton, New Wales of the South, produces a series of portraits of the aboriginal populations of Clarence Valley, marketed in the form of portfolios from the 1870s.

Combining exoticism and pictorial tradition, his pictures met with great success. Despite this problematic production context and the sometimes artificial nature stagings, this visual heritage is now a resource important for the descendants of the communities. In Australia, research have been undertaken since the 1990s to obtain information on the models, their identity and their territory of origin. The photography model known as “Mary Ann of Ulmarra” was identified in 2013 as Mary Ann Williams, née Cowan, through research conducted by one of his descendants.

Text from the exhibition

John William Lindt (Australian born Germany, 1845-1926)

Mary Ann of Ulmarra (Mary Ann Williams, née Cowan)

1873

Albumen print

Lindt took at least sixty photographs in this series of studio portraits of Clarence River Aborigines, although extant albums usually contain fewer than a dozen each. When first published, these studio tableaux were regarded as accurate. Reference: An Eye for Photography: the camera in Australia / Alan Davies. Carlton, Vic: Melbourne University Press, 2004, p. 60.

Antoine Julien Nicolas Fauchery (French, 1823-1861) and Richard Daintree (Australian born United Kingdom, 1832-1878)

Untitled (Two Aborginal Australian men and three women posing in front of a studio backdrop)

Victoria possibly Mt Franklin, 1858

9.20 x 21.20cm

John Watt Beattie (Australian born Scotland, 1859-1930)

The Pinnacle & Dream Pipes, Mt Wellington, Hobart, Tasmania

Australia, 1880-1890

Albumen paper print

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

John Beattie

John Beattie (1859-1930) came to Tasmania from Scotland at the age of nineteen, in 1878. Within a year, he was using the brand-new dry-plate photographic technique to take a series of views of Lake St Clair. He joined the Anson Brothers studio, and worked with the three siblings until he bought them out in 1891. In the 1890s he established a museum of curiosities he had collected. The first of the island’s wilderness photographers – with a keen interest in preservation of the environment – Beattie became the ‘official’ photographer for the Tasmanian Government. In addition to his well-known series of photographs of convicts, he made a number of portraits of Aboriginal people, of whom he said ‘for about thirty years this ancient people held their ground bravely against the invaders of their beautiful domain.’

Text from the National Portrait Gallery

Of Scottish origin, John Watt Beattie landed in Australia in 1878. The following year, he moved to Tasmania to a farm in New Norfolk, northwest of Hobart. Feeling more interest in going out in the bush than for the work of the farm, he then devotes himself to the photography of countryside. He was appointed official government photographer of Tasmania in 1896. Able to promote his work, he also enthusiastically supported the development of the tourism industry. In 1906, he traveled to Melanesia, Polynesia and the Norfolk Islands and derives hundreds of widely distributed photographs.

Text from the exhibition

Charles Woolley (Australian, 1834-1922)

William Lanne

1866

Albumen silver photograph

William Lanne (1834-1869), also known as King Billy or William Laney, is said to have been Truganini’s third partner. Lanne was captured along with his family in 1842 and taken to the Aboriginal camp at Wybelenna on Flinders Island. He moved for a time to Oyster Cove in 1847, before spending the years until 1851 in a Hobart orphanage. Four years later he joined a whaling ship. Regarded as the last surviving male of the Oyster Cove clan, Lanne died in March 1869 from a combination of cholera and dysentery. Following his death an argument broke out between England’s Royal College of Surgeons and Tasmania’s Royal Society over who should have his remains for scientific purposes. A member of the College of Surgeons, William Crowther, managed to break into the morgue where Lanne’s body was kept, decapitating the corpse, removing the skin and inserting a skull from a white body into the remnants. The Royal Society, discovering Crowther’s work, moved to thwart any further violations by amputating the hands and feet and discarding them separately. In this state, Lanne’s body was buried.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

Charles Alfred Woolley (17 December 1834-1922) was born in Hobart Town, Tasmania, Australia. He was an Australian photographer but also created drawings, portraits and visual art. He is best known for his photographic portraits of the five surviving Oyster Cove Aboriginal people taken in August 1866 and exhibited at the Intercolonial Exhibition of Australasia colonial exhibition in Melbourne the same year. …

In August 1866, Woolley took photographic portraits in his studio of the five surviving Oyster Cove Aboriginal people which became his best known work. These were exhibited at the Intercolonial Exhibition of Australasia colonial exhibition in Melbourne later that year. Two of the portraits were of Truganini, a female, and William Lanne, also known as King Billy.

These works are now exhibited in the National Library, and the State Libraries of New South Wales, Tasmania and Victoria. James Bonwick’s publication The Last of the Tasmanians (1870) included several of the photographs and shortly after engravings started to appear. Woolley exhibited the prints again in 1875 at the Victorian Intercolonial Exhibition. A few of the original sets survive, mainly in English collections, as well as copies that J. W. Beattie made.

After Lanne’s death in 1869, his grave was desecrated and his body mutilated and a full sized bust was produced by an artist named Francisco Santé. The Evening Mail advertised that it could be seen for a “small fee”. Though Woolley was not known as a sculptor, the Hobart Town Examiner reported that “numerous” busts he had produced were at Walch and Sons and Birchall’s bookshops.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Installation view of the exhibition Photographs. An Early Album of the World (1842-1911) at the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris showing the section ‘Conquering souls and spreading the word’ with, at left, three photographs by Augustine Dyer (Australian, 1858-1931) of Papua New Guinea (1884, see below)

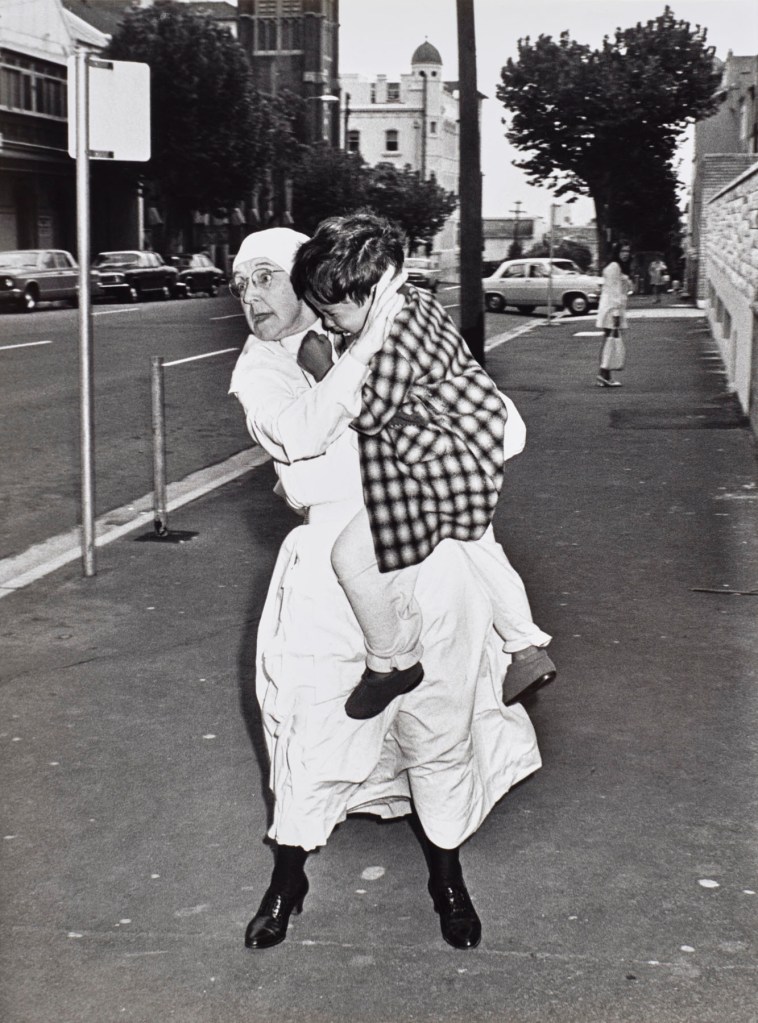

Conquering souls and spreading the word

The movement of colonial conquest also proceeded through missionary work where competition between congregations and between nations played out, much like at the political level. The Pacific was a place of rivalry between the United Kingdom and France. Protestant societies established from 1875 onwards in south-eastern New Guinea found themselves in competition with the Catholic missionaries. National alliances were formed between explorers and missionaries, promoting each other’s work. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the development of illustrated travel press allowed these heroic stories to be shared with a wide audience. Conferences with photo projections organised by the Geographical and Anthropological Societies were part of this process, combining different sources of images and narratives and establishing a lasting visual culture of the exotic.

Text from the exhibition

Augustine Dyer (Australian, 1858-1931)

View from Dinner Island, China Strait, H.M. Ships “Nelson” and “Espiègle” at anchor, Papua New Guinea

1884

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Dyer was the Australian Government Printing Office photographer who went to British New Guinea with John Paine (a studio photographer), for the purpose of recording the British annexation of the territory. He travelled more extensively with Paine in 1884 through PNG visiting Port Moresby, Motu-Motu, Kerepunu, etc.

Augustine Dyer (Australian, 1858-1931)

View from Dinner Island, China Strait, H.M. Ships “Nelson” and “Espiègle” at anchor, Papua New Guinea (detail)

1884

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Taking as its starting point the photography collection of the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, a reference collection for the representation of the extra-European world in the early years of photography, the exhibition focuses on the trajectories and geographies of the medium outside Europe in the 19th century, from its invention. Through a selection of nearly 300 photographs taken between 1842 and 1911 in Asia, Africa, Oceania, and the Americas, it seeks to better understand the phenomenon of the global dissemination of photography and the regional histories of non-European photography.

A visual collection of the world

Many places in the world became accessible through photography after the official announcement of its invention. The technical details of the daguerreotype were revealed in Paris in August 1839 and, in September, the darkrooms were loaded onto ships and crossed the borders of Europe. A tool associated with Western technological modernity, taken on countless voyages and scientific and military expeditions around the world, the medium of photography was used in the second half of the 19th century to investigate everywhere on the globe. From Mexico to Gabon, photography was in turn an instrument of description and the visual appropriation of landscapes and monuments, a tool for knowledge and the control of populations, and an object of diplomacy with the local elite. European colonial expansion was one of the driving forces that greatly accelerated global photography.

Dissemination and local appropriation

The new medium spread throughout the world from the 19th century, with very varied adoption rates in different regions. Europeans were no longer the only ones experimenting with, commissioning and marketing photography. Its local roots can be linked to the relations of countries with the West and to the relationship of societies to images. The exhibition, which presents the work of European and local photographers on four continents, seeks to better understand the development and appropriation of the medium around the world on a local scale by bringing to light lesser-known photographers, sponsors, phenomena and photographic forms, in an attempt to rebalance a history of photography that too often focuses on Europe and the United States. In many regions, from Colombia to West Africa to Madagascar, and from Iran to Japan to India, photography was adopted and sometimes adapted to social uses and local cultures and in many places seems to satisfy the desire for self-representation and the construction of modern identities. If cameras and photographers travelled, their models also travelled. The indigenous elites made regular diplomatic visits or came to Europe for training. From the 1860s, many photography studios were set up in large cities to meet the demands of tourists looking for exoticism. But the studios’ decor also attracted a local clientele wanting to preserve the memory of their loved ones.

How far should photography be taken?

The 19th century in Europe was characterised by a need to accumulate objects, knowledge and also territory. Through photography, landscapes became lands to be mapped and conquered, and their inhabitants subjects to be studied. In the scientific field, the natural history model influenced the use of photography. It contributed to the myth of virgin territories and was a tool in the growing geographical discipline, making claims of exhaustivity: see everything, photograph everything. But this thirst for images, which began in 1840 in Europe and then spread rapidly throughout the world, met with contrasting situations. From the beginning, the question of limits arose: how far to go, under what conditions and for what purposes should a photograph be taken? This was sometimes a technical challenge, but above all an ethical question when it involved showing the horrors of wars or producing the image of scenes or objects that were supposed to remain hidden. Some photographers may have tricked, coerced or negotiated to get an image.

The selection of works, mostly taken from the quai Branly photography collection, highlights the diversity of photographic practices outside Europe at their origins and reveals early testimonies of indigenous photographers. By revealing the scientific, military and commercial uses, as well as the memorial and social functions of photography, and by presenting a wide range of objects and techniques, the exhibition invites us to re-examine today the meaning of the photographic gesture in these different non-European contexts.

Publication

Mondes photographiques, histoires des débuts

The book that accompanies the exhibition broadens its scope of study to offer the first decentralised history of early world photography. Taking as its base the photography collection of the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, a reference collection for the representation of the extra-European world in the early years of photography, it deepens this study to focus on the trajectories and geographies of the medium outside Europe from the 19th century. Co-publication musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac / Actes Sud 400 pages. €69

Text from the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Eugene Thiesson (French, 1822-1877)

Botocudo

1844

Daguerreotype

10.5 x 8cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Eugene Thiesson

In 1844, two Brazilian Indians were brought to France by a certain Mr. Porte and are going to stay in Paris for a few months. This man baptised Manuel (and the young woman baptised Marie) in the press, will arouse interest certain among the anthropologists of the Natural History Museum. Werner, painter from the Museum, paints their portrait in watercolour, while Thiesson photographs them using the daguerreotype. They also lend themselves at a moulding session in the anthropology laboratory. The five daguerreotypes that remain today from the photography session show us two people with the top of the body undressed, and the bottom dressed of what appears to be European clothing.

Text from the exhibition

This man from the Canaries counts among the very first non-Europeans to have been photographed, probably in Paris. His portrait illustrates the first scientific publication offering daguerreotypes to visually appreciate the anatomic characteristics of human skulls. The Botocudo Indian from Brazil was photographed in Lisbonne, in 1844, but he visited Paris; his name was Manuel, and his wife was Maris. They lodged with some man called Porte, who brought them to the Museum. There, people wanted to make casts of their faces, their torsos, their arms and legs. Manuel and Marie walked across Marville’s Paris – across that city that was to disappear; they walked on the Boulevard du Temple and might have even visited the theaters. Actors, spectators? Dressed, costumed, naked? Under applause, mockery, examination, or measurement?

Catherine Darley. “Ghosts (1) – Shadows,” on the Poemas del río Wang blog 10/08/2012 [Online] Cited 07/05/2023

Luis Garcia Hevia (Colombian, 1816-1887)

Untitled (portrait of a man)

c. 1843-1850

Colourized daguerreotype, mounted under passe-partout and under glass, encased in a gutta-percha box

Dimensions of the plate: 7.5 x 10cm

Dimensions of the assembly: 10 x 12.4cm

Dimensions with box open: 20.2 x 12.4cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Luis Garcia Hevia

Luis Garcia Hevia is the first Colombian photographer and daguerreotypist. He exhibited his first “two essays of daguerreotypes” at the exhibition of industry in Bogota in November 1841. He was also a painter and miniaturist.

Recreated Worlds: The Studios

In the second half of the 19th century, land and sea travel grow considerably. European colonial expansion is one of the driving forces behind the acceleration of global photographic coverage. If cameras and photographers travel, their models also travel. The indigenous elites make regular diplomatic visits or come to

train in Europe. During major universal and colonial exhibitions, population groups are moved and exhibited in European metropolises, between the 1870s and the beginning of the 20th century.

From the 1860s, many photographic studios set up in the big cities. The actors of this new commercial practice adapt to the demand of a tourist clientele in search of exoticism. Staging and props recreate artificial worlds. When the framing refocuses on the face, it is often to respond to the descriptive need of physical anthropology. But the decor of the studio attracts also a local clientele anxious to preserve the memory of their loved ones.

Faced with these portraits, many questions persist today: who were these individuals? What can we know of their interaction with the photographer and their participation at the time of the shot?

Jacques-Philippe Potteau (French, 1807-1876)

Charles Ozbee

Nd

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Jacques-Philippe Potteau (1807-1876)

In photography, the portrait genre has from the outset brought together goals and very different situations. Like today, it may have been used at recreational or law enforcement purposes, as a personal memento or as a means of recording. The very ambiguity of the medium lies in this possible permeability of domains: a family album image can leave the private sphere, a photograph made for an anthropological description can sometimes also be a true portrait, shedding light on the personality of its subject.

The images of Jacques-Philippe Potteau, produced for scientific purposes between 1860 and 1869 at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, confer a undeniable dignity to their models, sometimes photographed as part of diplomatic functions (embassies of India, Siam, Japan). Jean Lagrêne, Philippe Colarossi are closely associated with the artistic world, as models. If Jacques-Philippe Potteau, a technician employed by the Museum, took care to note the names of the people he photographs, the reason for their presence in the photographic workshop, or in the Parisian capital is not always known to us. This is currently under research.

Text from the exhibition

Jacques Philippe Potteau (French, 1807-1876)

Mostapha Ahmed (21), Nubian born in Mudrici d’Ungle

Paris, France, 1862

Print on albumen paper

18 x 12.7cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Jacques-Philippe Potteau was a member of the anthropology department of the Muséum d’histoire naturelle, Paris. Between 1860 and 1869 he made a series of ethnographic portraits for the museum under the collective title Collection anthropologique du Muséum de Paris. In 1862 Potteau succeeded Louis Rousseau as the departmental photographer. Potteau showed his work at the London Photography Exhibit in 1862 and 1863, and the 1863 Paris International Photography Exhibit.

Jacques Philippe Potteau (French, 1807-1876)

Mostapha Ahmed (21), Nubian born in Mudrici d’Ungle (detail)

Paris, France, 1862

Print on albumen paper

18 x 12.7cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Jacques Philippe Potteau (French, 1807-1876)

Emir Abd el-Kader (57), born in Maskara (Province of Oran, Algeria)

Paris, 1865

Albumen paper print

Paris, musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Crédit photo: © musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN – Grand Palais / image musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Capture the distance

As early as the 1840s, cameras were on board on expedition ships departing from Europe. sailors, explorers, archaeologists, missionaries, artists are among the first experimenters of this new technology in remote regions, which are gradually passing under the yoke of the colonial powers. From Mexico to Gabon, photography is in turn an instrument of description and visual appropriation landscapes and monuments, a knowledge and control tool populations, or even an object of diplomacy vis-à-vis the local elite.

If the camera records with the same acuity the architectural detail, the landscape grandiose and the faces crossed, the authors gathered here turn out to be excellent technicians with a personal eye. Their travelogues relate the difficulties overcome: technical challenges, climatic constraints or even reluctance of local populations to pose. But these spectacular images, carried out in more or less accessible places, are also the result of a collaboration with many less visible local intermediaries: guides, interpreters, informants or porters – necessary to transport photographic equipment – played a decisive role.

Text from the exhibition

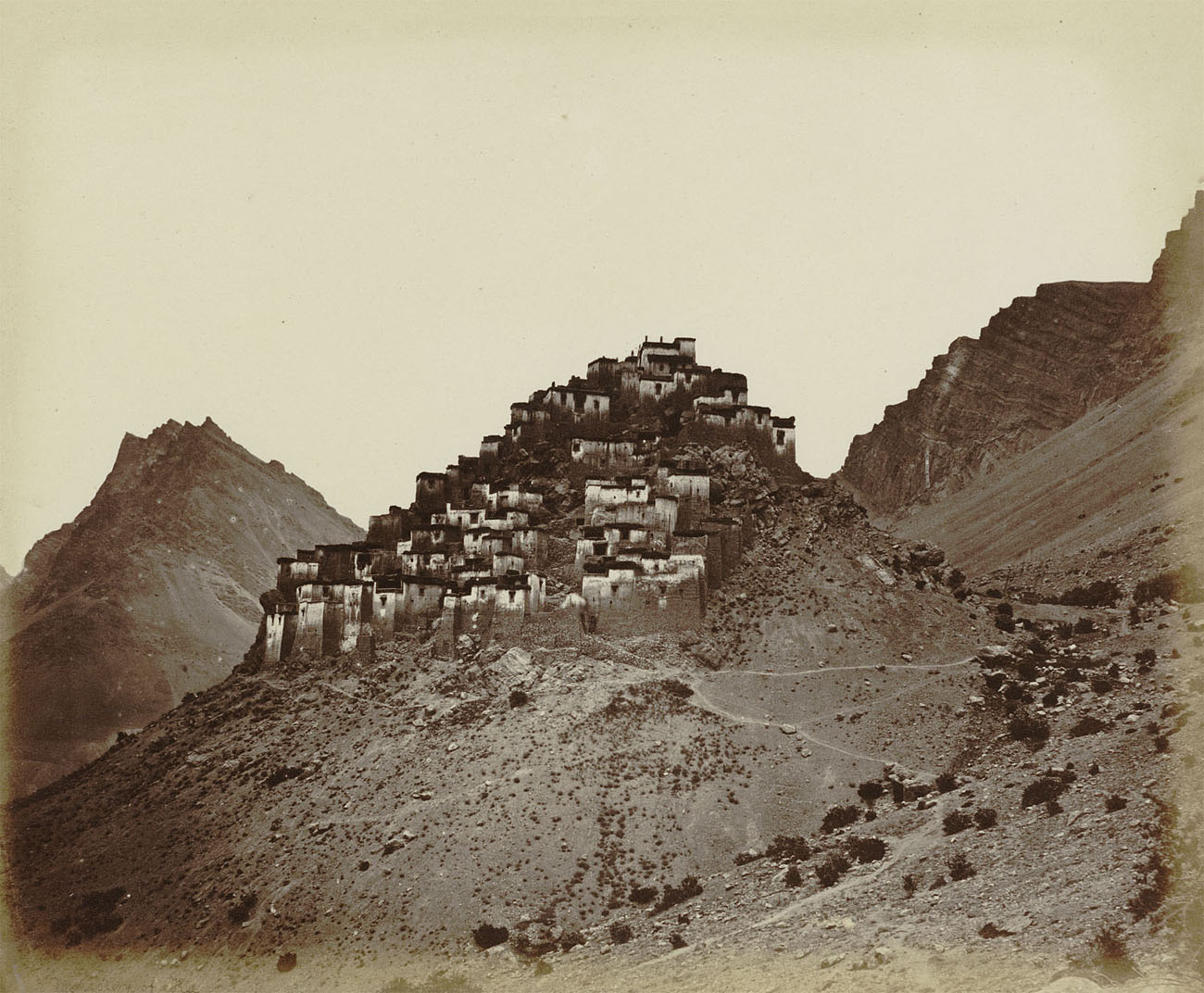

Philip Henry Egerton (Welsh, 1824-1893)

“Kee Monastery”, Pl. 22, Journal of a tour through Spiti, to the frontier of Chinese Tibet

Tibet, 1863

Album comprising 37 albumen prints

Dimensions of the album: 29 x 38.4cm

Dimensions of the prints: 21.6 x 26.7cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Philip Henry Egerton (Welsh, 1824-1893)

“Kee Monastery”, Pl. 22, Journal of a tour through Spiti, to the frontier of Chinese Tibet (detail)

Tibet, 1863

Album comprising 37 albumen prints

Dimensions of the album: 29 x 38.4cm

Dimensions of the prints: 21.6 x 26.7cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Philip Henry Egerton

The Briton Philip Henry Egerton worked for most of his life as senior civil servant for the colonial regime in northern India. He realises these photographs during a semi-official mission in the Himalayas, trying identify alternative routes for the wool trade across the border

India and Chinese Tibet. The Kangra and Kullu valleys, as well as the sites of Spiti and the Bara Shigri glacier are thus photographed for the first time. The images are published, accompanied by the story of their author, in 1864, with the support of the government of Punja.

Text from the exhibition

Philip Henry Egerton (Welsh, 1824-1893)

Shigri Glacier – From the River (Main View)

Negative June – August 1863; print 1863-1864

From Journal of a Tour Through Spiti, To The Frontier of Chinese Thibet, With Photographic Illustrations

Albumen silver print

21.6 × 26.5cm (8 1/2 × 10 7/16 in.)

Credit Line: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Philip Henry Egerton (Welsh, 1824-1893)

Shigri Glacier – Lower View

Negative June – August 1863; print 1863-1864

From Journal of a Tour Through Spiti, To The Frontier of Chinese Thibet, With Photographic Illustrations

Albumen silver print

21.6 × 26.5cm (8 1/2 × 10 7/16 in.)

Credit Line: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Désiré Charnay (French, 1828-1915)

Palace of governor in Uxmal Yucatán

Mexico, June 1860

Assembly of two prints on paper albumen

32.8 x 84.8cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Desire Charnay

Improvised archaeologist and photographer with a taste for travel, Désiré Charnay is known to be the first to have brought back from several archaeological sites Mexicans a harvest of spectacular images. He uses the process of the negative on wet collodion glass, which requires him to carry heavy equipment. His fame was ensured by the publication, in 1861-1862, of the album photographic American cities and ruins.

Local stories and self-images

Europeans are not the only ones to experiment, order and market photography from the 19th century. The new medium is spreading to scale across the globe and has very variable rates of adoption depending on the region. Its local roots can be linked to the countries’ relations with the West or the relationship of societies to images. In Qajar Iran, in Siam (Thailand present day), in the princely courts of India and Java, royalty has been a patron enthusiast of photography and accelerated its growth by designating official photographers and importing equipment. The leaders take awareness of the potential of photography for the representation of power and the assertion of their authority. In India, Japan, China, West Africa and in Madagascar, indigenous photographers are getting professional training to practice, open their commercial studio in the major port cities, and very often work for a wider clientele, among the local and colonial elite. Photography is appropriate and adapted to social uses, it sometimes mixes to local visual traditions – such as painting or calligraphy – and seems in many places respond to the desire for self-representation and construction modern identities.

Royal appropriations of photography in Iran and Thailand

The monarchs Naser al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896), in Iran, and Mongkut in Siam (Rama IV, r. 1851-1868), seduced by the technology and the possibilities of dissemination of the royal image, were important patrons. Naser al-Din Shah, defender of the arts and open to Europe, initiated himself into the practice, becoming an amateur keen. It promotes the development of photography through the diversity of actions which he led: in 1858, he established the Royal Photography Workshop within the of the Golestan Palace in Tehran, promotes the teaching of technique at school polytechnic of Dar ol-Fonoun, imports equipment, translates manuals, and appoints official court photographers who are given the title of Akkasbashi. Siam’s science-savvy King Mongkut also ramps up production photography at court. The Thai Francis Chit, who receives the title of “photographer of His Majesty the King of Siam”, produced several portraits of the royal family and views of official court events.

Text from the exhibition

Anonymous photographer

Half-length portrait of a 77-year-old man

Kyoto area, Japan, February 1890

Ambrotype

11 x 8.5cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

In Japan, a considerable boom during the Meiji era (1868-1912)

In Japan, photography developed as soon as the country opened up to trade international in 1859, and experienced considerable growth during the Meiji era (1868-1912), period of great modernisation. Uchida Kuichi and Ueno Hikoma, trained in Nagasaki, are among the most famous Japanese photographers of their time. They have developed a unique style with a pronounced taste for theatricality and sometimes humour. The production of ambrotypes, known as garasu shashin – “photography on glass” – is experiencing a particular boom in the field portraiture from the 1860s. Unique objects, they are mounted in boxes in raw paulownia wood, with traditional geometric shapes simple, used to preserve calligraphy or personal property.

The ambrotypes were intended for the private sphere of Japanese families, wishing to pass on the portraits of their loved ones as an inheritance. The tekagami-style accordion albums, richly decorated with gilding and sophisticated paintings, originally planned to accommodate calligraphy, have been diverted from their traditional use to receive prints large format photographs of Ichida Sota and Suzuki Shin’ichi II.

Anonymous photographer

Half-length portrait of a 77-year-old man (detail)

Kyoto area, Japan, February 1890

Ambrotype

11 x 8.5cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Tamoto Kenzō (Japanese, 1832-1912)

Ainu with boat

Hokaido, Japan, c. 1874

© Kenzo Tamoto © Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Tamoto Kenzō (田本 研造, 1832-1912) was a Japanese photographer. He was born in Kumano, in the Mie Prefecture of Honshu. When he was twenty-three, he moved to Nagasaki to study western culture. In 1859, he relocated to Hakodate, where he lost a foot due to frostbite. The surgeon who amputated his foot had an interest in photography, specifically ambrotypes, and Tamoto became his apprentice. It was not until 1866 that he began working as a photographer. In 1867, he photographed the construction of the last castle to be built in Japan, Fukuyama Castle. Tamoto took photographs of military leaders Enomoto Takeaki and Hijikata Toshizō during the Battle of Hakodate between 1868-1869. Tamoto opened his own portrait studio in Hakodate in 1869. Starting in 1871, he documented the improvements to infrastructure in the Hokkaido region, eventually presenting 158 photographs of the process to the Settlement Office.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Tamoto Kenzō (Japanese, 1832-1912)

Ainu with boat (detail)

Hokaido, Japan, c. 1874

© Kenzo Tamoto © Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

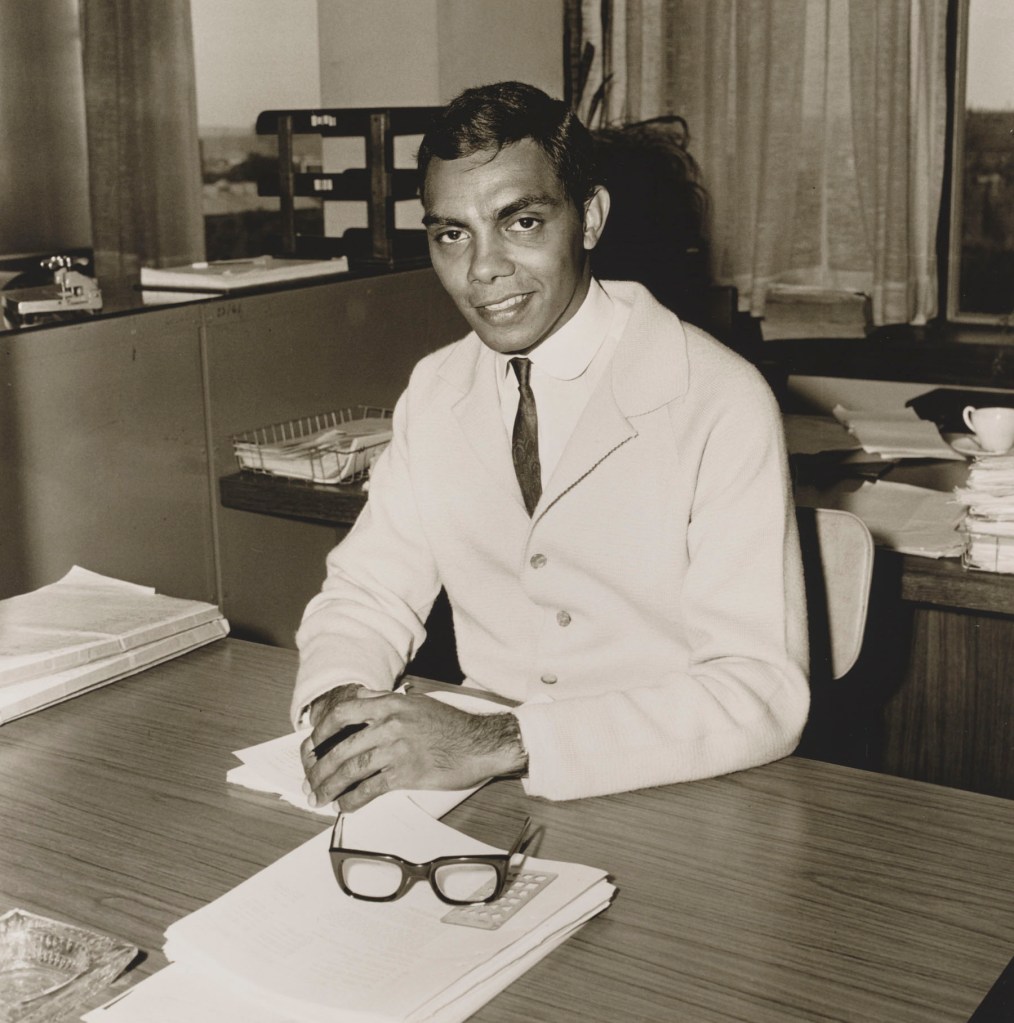

In India, a technology adopted by the elites

Introduced in India in 1840, photography was used by the authorities British and quickly adopted by the Indian elite. Studios set up in major port cities like Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. Active members of the Photographic Society of Bombay, Narayan Dajee and Hurrychund Chintamon are among the first native photographers to practice from the 1850s with the local elite, Brahmans, members of the government, and at the same time participate in colonial projects ethnographic documentation. The technology aroused enthusiasm very early on many maharajas. Famous Indian photographer Lala Deen Dayal received the title of official photographer of the ruler of Hyderabad in 1884. In some princely states like Indore, Udaipur and Mewar, photography of painted court is a great success and is part of the tradition of royal portraiture of pageantry. Enlarged prints are coated with a vivid layer of paint and opaque, which emphasises the abundance of jewels and the sumptuous character clothes.

Text from the exhibition

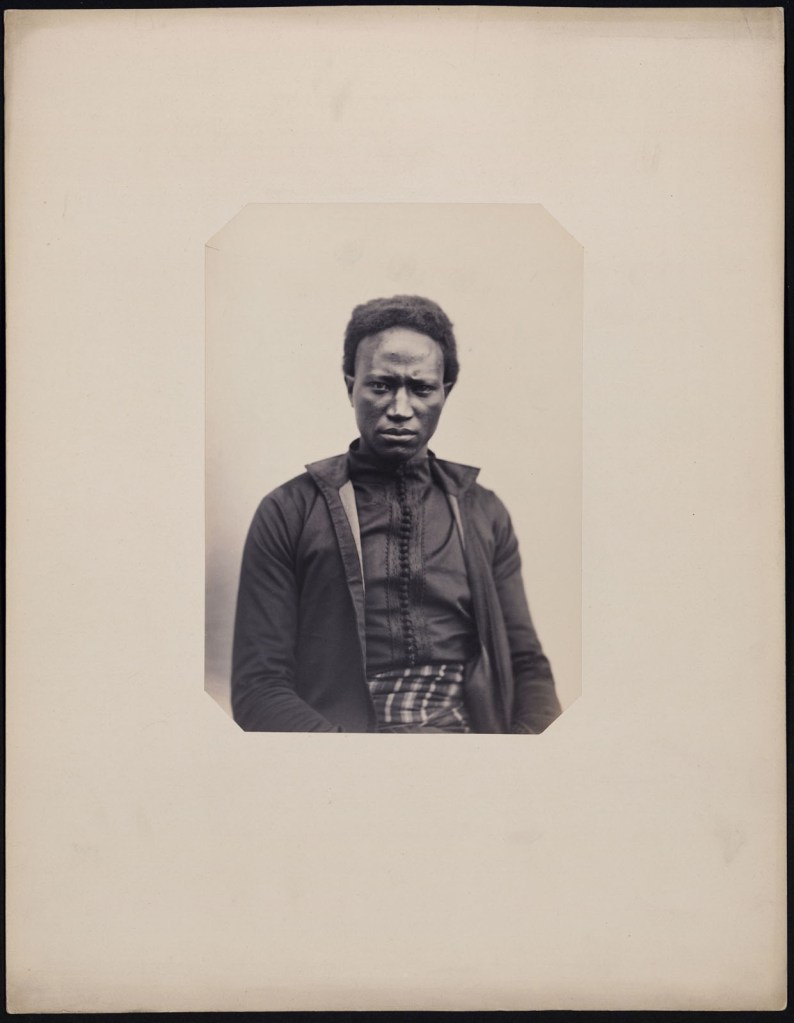

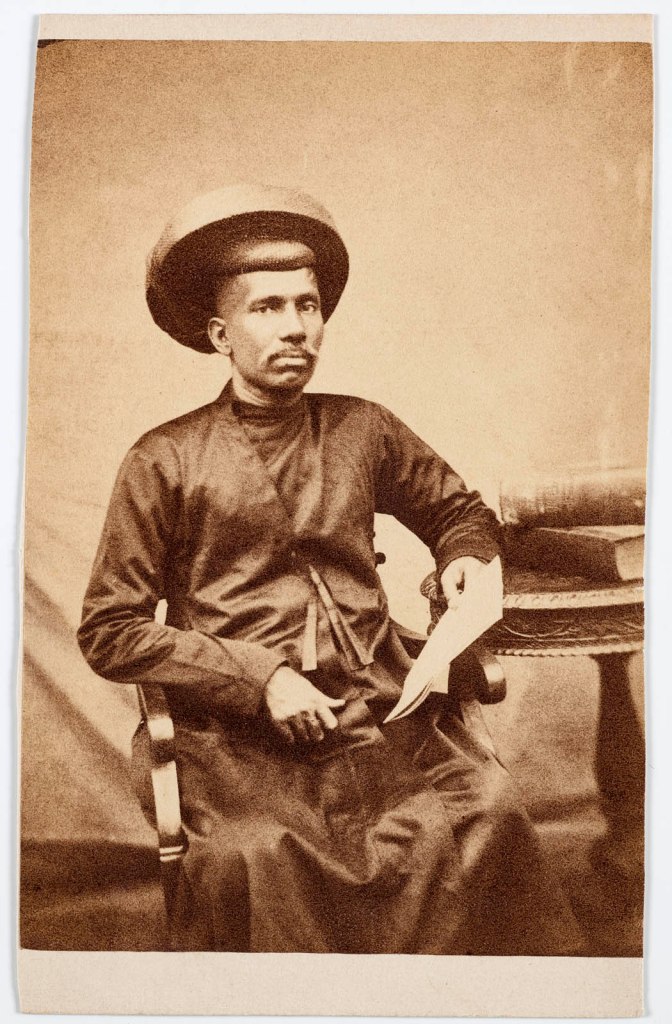

Hurrychund Chintamon (Indian)

Untitled (Portrait of a man)

1860s-1880s

Albumen print

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

One of India’s earliest commercial photographers who specialised in portraiture, Hurrychund Chintamon was based in Bombay (now Mumbai). He received his training at Elphinstone College in 1855 under WHS Crawford, a secretary of the Photographic Society of Bombay, where Chintamon also exhibited his work the following year. He subsequently set up his photography studio in the city, initially photographing members of local mercantile families and later expanding his clientele to aristocracy and important political, administrative and literary figures, including Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy and Manickjee Antarya.

When Elphinstone introduced a course in photography in 1855, under instruction from the British East India Company, Chintamon was among the first batch of forty students to enroll. He graduated in 1856 with distinction, having twice earned the best photographs prize. The same year, he exhibited his photographs at the Bombay Photographic Society, along with others such as Narayan Daji, gaining the visibility he needed to operate as an independent professional. He also went on to produce a number of ethnographic images, some of which were displayed at the Exposition Universelle, or the Paris International Exposition, of 1867 for industrial, art and craft manufactures. His studio, Hurrychund & Co., which he set up at Rampart Row in 1858 flourished until 1881, when it ceased operations. …

Accompanying the proliferation of independent photography studios in the mid-nineteenth century, was the development of a hybrid aesthetic, seen also in Chintamon’s work. He evolved a visual style that combined the Victorian iconographies of class and refinement with the Indian symbols of ethnicity, caste and status. In staging his sitters, he used the popular European conventions of painted backdrops as well as props such as printed carpets and flower vases. The sitters were often posed or arranged to suggest an air of casualness or informality, in conspicuous contrast to their own self-conscious formality – likely a result of having to hold still during extended individual exposure times. This unintended tension between setting and sitter is another notable characteristic of Chintamon’s portraits.

Anonymous. “Hurrychund Chintamon,” on the Mapacademy website April 21, 2022 [Online] Cited 27/05/2023

Anonymous photographer

Portrait of a Maharaja of the Royal Family. Holkar, princely state of Indore

1910-1920

Silver print enhanced with gouache

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Johnston & Hoffmann (active 1880-1950).

The Maharani of Nepal and her Ladies in Waiting

Nepal, 1885-1894

Albumen print

musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Image: Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Johnston & Hoffmann (active 1880-1950).

The Maharani of Nepal and her Ladies in Waiting (detail)

Nepal, 1885-1894

Albumen print

musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Image: Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

P.A. Johnston and Theodore Julius Hoffmann

Of British origin, P. A. Johnston and Theodore Julius Hoffmann founded the Johnston & Hoffmann studio, at its time the second largest European studio important in India. Established in Calcutta in 1882, they opened eight years later a annex to Darjeeling. Their studio is best known for its portraits of locals and royalty from Nepal, Sikkim and Tibet.

Text from the exhibition

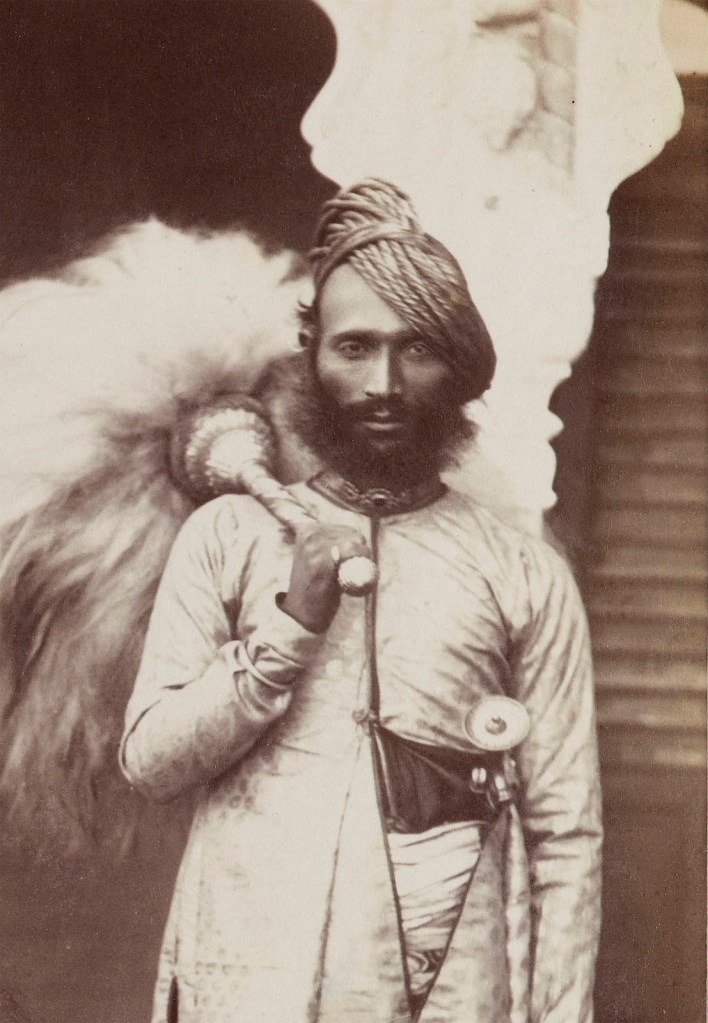

Lala Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Portrait of Sir Pratab Singh, Maharajah of Orchla, with his entourage

India, 1882

Albumen print

musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Lala Deen Dayal

Raja Lala Deen Dayal (Hindi: लाला दीन दयाल; 1844-1905; also written as ‘Din Dyal’ and ‘Diyal’ in his early years), famously known as Raja Deen Dayal) was an Indian photographer. His career began in the mid-1870s as a commissioned photographer; eventually he set up studios in Indore, Mumbai and Hyderabad. He became the court photographer to the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad, Mahbub Ali Khan, Asif Jah VI, who awarded him the title Raja Bahadur Musavvir Jung Bahadur, and he was appointed as the photographer to the Viceroy of India in 1885. He received the Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria in 1897.

Lala Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Portrait of Sir Pratab Singh, Maharajah of Orchla, with his entourage (detail)

India, 1882

Albumen print

musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Lala Deen Dayal (Indian, 1844-1905)

Portrait of Sir Pratab Singh, Maharajah of Orchla, with his entourage (detail)

India, 1882

Albumen print

musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Installation view of the exhibition Photographs. An Early Album of the World (1842-1911) at the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris showing the section ‘Composite photographs in Mexico’

Composite photographs in Mexico

In the history of painted photography practices, colourisation often aims to embellish the print considered monochromatic and dull. A set of photographs painted by landscape artist Conrad Wise Chapman show a association of these two techniques around picturesque and popular subjects. Other forms of formal hybridisation are attested in Mexico. Three shots set with a medallion were partially covered with feathers in the colours shimmering, to highlight clothes and certain elements of the decor. These composite objects are rare testimonies that combine the art of featherwork, widespread in Mexico during the pre-Hispanic and colonial periods, with the new technique of photography. The figure of the peddler is attributed to the photographer Augustin Péraire [below] and the image of the three women is a reproduction of a print of the popular figure showing the “China poblana”.

Wall text from the exhibition

Augustin Péraire (active c. 1860)

Portrait of a Man

c. 1867

Print on albumen paper enhanced with gouache and partially feather coloured, laminated on card size cardboard. Oval frame format, frame and gilt window, black and tan passe-partout swirl effect

13 x 9.2cm

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Installation view of the exhibition Photographs. An Early Album of the World (1842-1911) at the musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Paris showing at second left, W.J. Sawyer’s Mr Sawyer, photo man (Nigeria, 1880-1890, below)

W.J. Sawyer (Nigerian)

Mr Sawyer, photo man

Nigeria, 1880-1890

Albumen paper print

Print on aristotype paper

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Photo of W. J. Sawyer and his sons taken in Calabar (possibly at his studio). W. J. Sawyer was a photographer based in Calabar, mostly active during the late 19th century and early 20th century, having photographed the Oba of Benin during the period of his craft.

W.J. Sawyer

The biography of W. J. Sawyer is still quite incomplete. He takes, on demand of the Spanish Commander Francisco Romero, several photographs in Bioko (current Equatorial Guinea), in 1883. The images are shown the same year at the International Colonial and Export Exhibition in Amsterdam. The picture showing a man accompanied by two boys could be a self-portrait of the photographer, as the title on the back suggests.

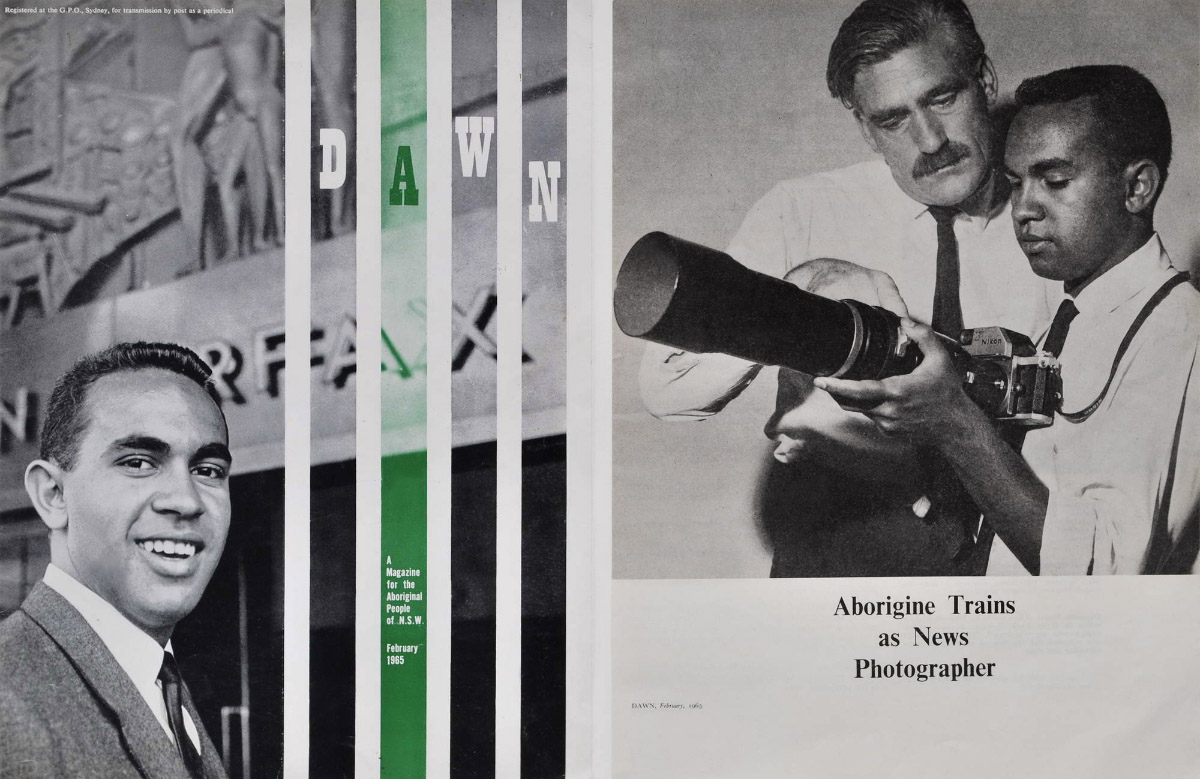

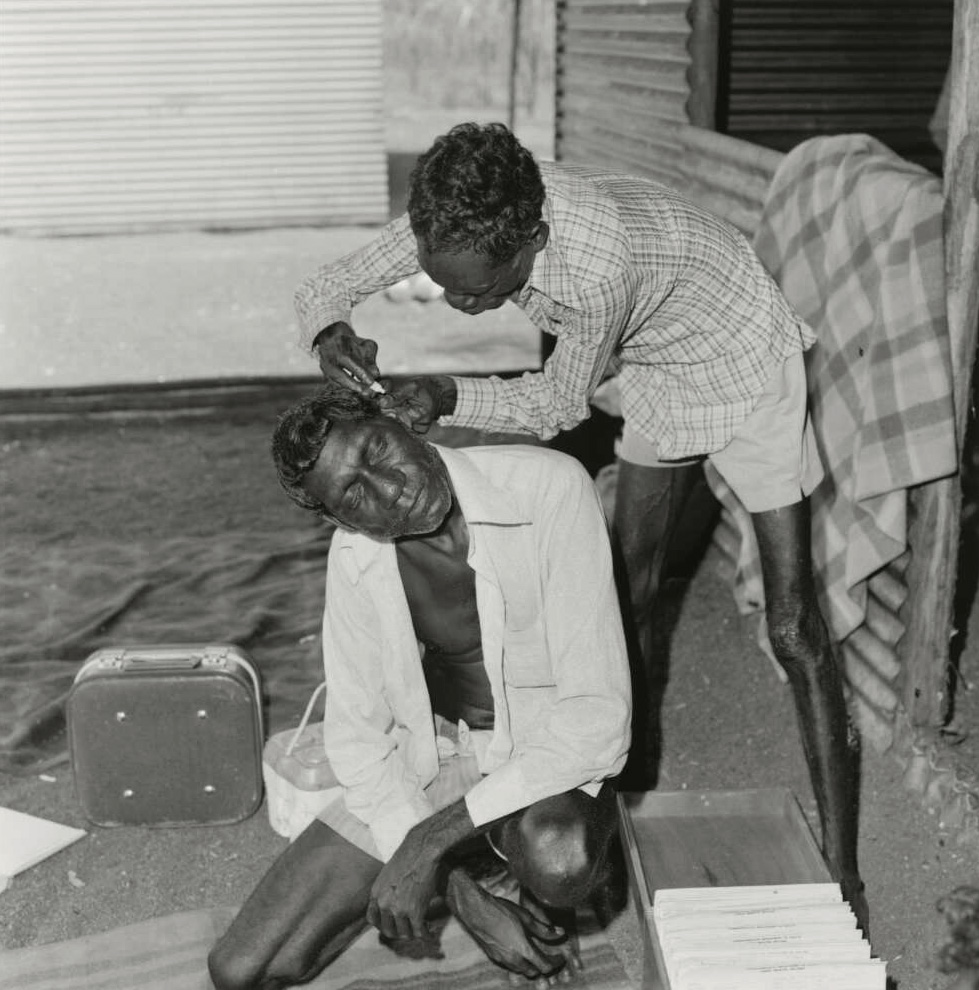

Rapid growth in West Africa

Photography was quickly adopted in many regions in the world from the 1840s to the 1860s. West Africa combines several factors which have fostered its rapid growth. Many ports connect the cities with each other and with the European continent, facilitating transatlantic and regional trade. In Freetown (current Sierra Leone), Lagos (current Nigeria), Libreville (current Gabon) established communities made up of elders freed and returning slaves from North and South America and the Caribbean. A cosmopolitan culture reigns in these cities where trade can develop.

As early as 1853, the African-American Augustus Washington left the United States and set up a daguerreotype studio in Monrovia. In the 1860s, Francis W. Joaque or J.P. Decker practice photography on an itinerant basis on the coast. These photographers respond to a local demand for photography loved ones or events to remember. They also include a clientele European, Joaque realising for example many portraits of the explorer Italian Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza. The Lutterodt dynasty establishes several studios photographers who operate in Accra (current Ghana) and Freetown between the years 1870 and 1940.

Text from the exhibition

Jonathan Adagogo Green (Nigerian, 1873-1905)

Last photo of Chief Henry Long John. Behind him stands his successor

Nigeria, 1895

Albumen print

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

J.A. Green

J. A. Green is one of West Africa’s most prolific photographers. Born in Nigeria, he is the son of a palm oil merchant. He practices photography from 1891 and provides images to a clientele African and European. He also trains other photographers. In this image, Green photographs a stage at the leader’s funeral slaver Amonibienye Ofori Long John. The tanda burial custom involves, for the elites, the public presentation of the body of the deceased dressed in his clothes of pageantry. Son Henry Obulu supports his father’s jaw to affirm his position as legitimate heir.

Text from the exhibition

Jonathan Adagogo Green

Jonathan Adagogo Green (J. A. Green), born in the village of Ayama (Peterside), Bonny (Rivers State, Nigeria) in 1873. The son of Chief Sunju Okoronkwoye Dublin Green and Madame Idameinye Green, he was looked after by his uncle Uruasi Dublin Green after his father’s death in 1875. He attended school in Lagos and possibly Sierra Leone. It is unknown where he trained as a photographer but by 1891 he had set up his photographic practice in Bonny. His work covered a range of themes including portraiture of British colonial officers, European merchants, prominent chiefs and their families, scenes of daily and ritual life, commerce and building – a body of work that appealed to both local elites and expatriate clients. Green died in 1905 at the age of 32, after practicing in the Niger Delta for 14 years. His work is in held in a number of collections in the UK, USA and Nigeria.

Text from the exhibition

Jonathan Adagogo Green (1873-1905) was according to some sources the first professional photographer in what is now Nigeria to have ethnic origins in that area. He is significant in being a pioneering photographer in what is now Nigeria, noted for his documentation of the colonial power and local culture, particularly his Ibani Ijo community.

Green was born in Bonny, present day Rivers State. “He studied photography in Sierra Leone and then established a studio in Bonny.” The area where he lived became part of the British Oil Rivers protectorate in 1884, which was renamed to the Niger Coast Protectorate in 1893. It was part of the Southern Nigeria Protectorate for the last few years of Green’s life, starting in 1900.

Green was active as a photographer for only a short lifetime, dying at the age of 32. “But during this period he was both energetically productive and remarkably adroit in serving both indigenous and colonial clienteles.” “When he set up shop his work was appreciated and rewarded by two very different communities.” His “strategic use of initials on his business cards and stamps… disguised his African origins”, part of his working with the colonial era officials.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Jonathan Adagogo Green (Nigerian, 1873-1905)

Last photo of Chief Henry Long John. Behind him stands his successor (detail)

Nigeria, 1895

Albumen print

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

William Ellis (British, 1794-1872)

Untitled (portrait of a woman)

1853-1865

Salted paper print

20.5 x 24cm

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

William Ellis (British, 1794-1872)

Untitled (portrait of a woman) (detail)

1853-1865

Salted paper print

20.5 x 24cm

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

William Ellis (29 August 1794 – 9 June 1872) was a British missionary and author. He travelled through the Society Islands, Hawaiian Islands, and Madagascar, and wrote several books describing his experiences.

Joseph Razafy (Madagascar, 1881-1949)

Untitled (portrait of two men and a woman)

Nd

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

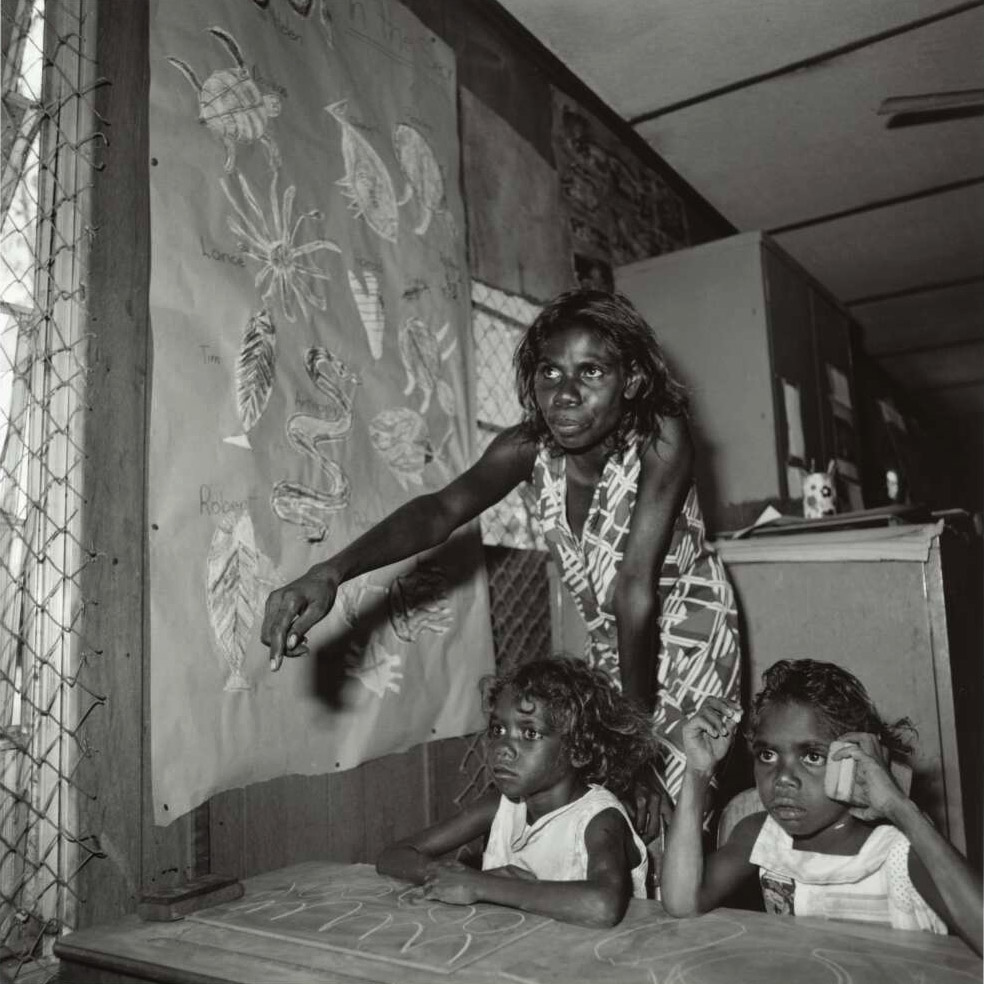

In Madagascar, photography as a tool of social distinction

Photography is introduced to Madagascar by the British missionary William Ellis [above]. First rejected by Queen Ranavalona I (r. 1828-1861), the technology was enthusiastically adopted during the reign of Radama II (r. 1861-1863) by the king himself, the court and the Malagasy elite, responding to the desire for individualisation and social distinction from high society. Several European photographers mentioned the ease and familiarity of the models with the device. From the 1890s, the first Malagasy studios won great success with a population wishing to design and maintain a self-image. The photos presented here are the work of this first generation Malagasy photographers, including Joseph Razaka based in Antananarivo and Joseph Razafy in Toamasina.

Text from the exhibition

Joseph Razafy (Madagascar, 1881-1949)

Untitled (portrait of two men and a woman) (detail)

Nd

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Joseph Razafy (Madagascar, 1881-1949)

Untitled (portrait of a woman)

Nd

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Ulke Brothers Studio (Julius Ulke and Henry Ulke)

Apsáalooke (Crow) delegation

1872

Albumen silver print from glass negative

8 x 10 in.

National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

Back row (standing) from left to right: Long Horse; Thin Belly; Bernard Prero (interpreter); unknown name, wife of Awé Kúalawaachish (Sits In The Middle Of The Land); Major F.D. Pease (agent); unknown name, wife of Uuwatchiilapish (Iron Bull); Frank Shane (interpreter); and Bear In The Water. Front row (seated in chairs) from left to right: Bear Wolf; White Calf; Awé Kúalawaachish (Sits In The Middle Of The Land); Uuwatchiilapish (Iron Bull); One Who Leads The Old Dog; and Peelatchixaaliash (Old Crow [Raven]). Front row (seated on the floor) from left to right: Stays With The Horses, wife of Bear Wolf; and Pretty Medicine Pipe, wife of Peelatchixaaliash (Old Crow [Raven])

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (American born Ireland, 1840-1882)

Photographs from Geographical explorations and surveys west of the 100th meridian Wheeler 1871-2-3

1871-1873

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Timothy H. O’Sullivan

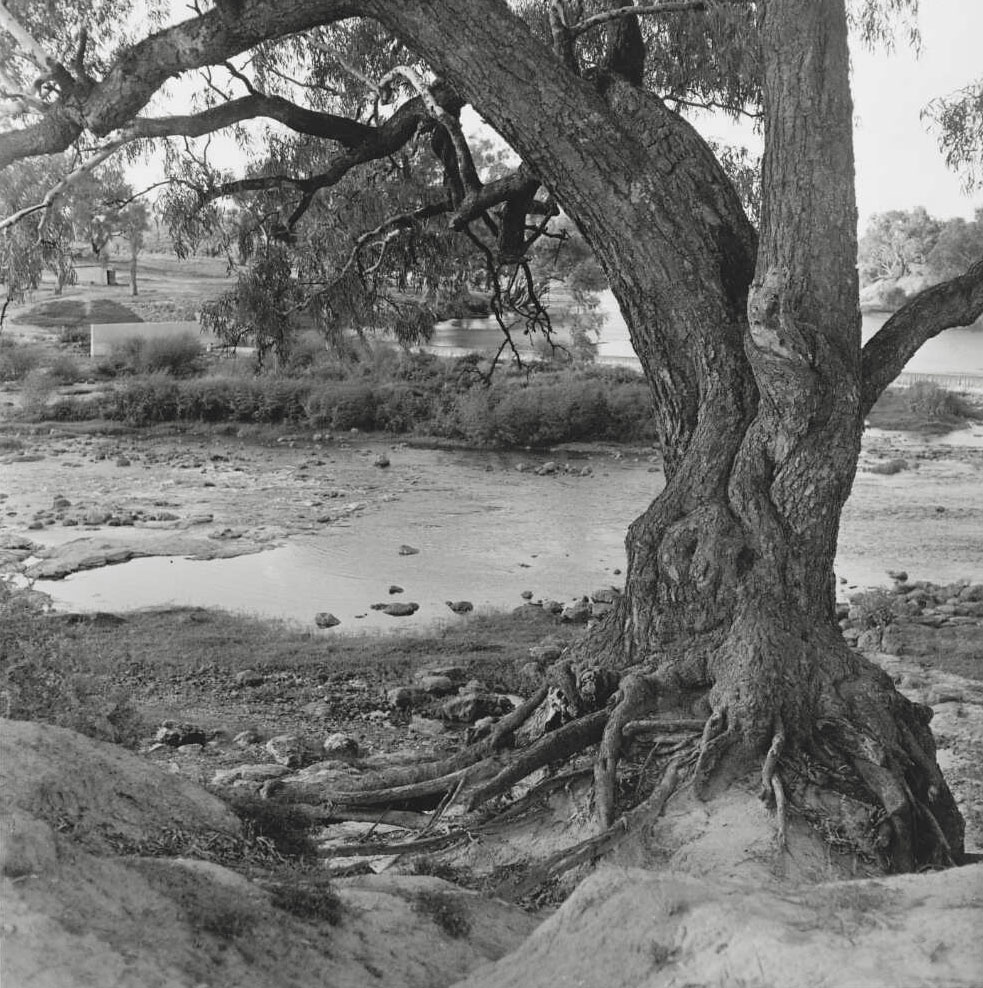

This series by Timothy H. O’Sullivan comes from the album Photographs from Geographical explorations and surveys west of the 100th meridian Wheeler 1871-2-3, consisting of fifty photographs of explorations in the Western United States (New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, etc.). The set shows mainly landscapes and natural sites, some portraits of Zunis, Apaches and Navajos, and views of architecture and monuments.

The limits of visibility

The thirst for images which manifested itself as early as 1840 in Europe and then rapidly in the whole world has encountered contrasting situations. From the beginning arose the question of limits: how far to go? Under what conditions do a photography ? For what purposes? Technical challenge sometimes but above all question ethics when it comes to bearing witness to the horrors of war, or when it comes to to produce the image of scenes or objects that are supposed to remain hidden. Some photographers could trick, coerce or negotiate. The images produced are remained secret or, conversely, circulated widely. The life of photographs after the shot is a fundamental element of this medium, they are led to undergo multiple changes of meaning depending on the way we perceives them, from which they are presented. In this section are photographs that evoke certain situations limits: images of conflicts shown or hidden, sacred places of which a part remains invisible, images obtained by trickery. These photographs are not shown as trophies but as traces of practices that we can re-examine today.

Uncover the Sacred

For many photographers, the attraction of the forbidden or the opportunity to attend a singular event played into the desire to create an image. We consider

today with a certain reserve these images of masks or places Holy. While they may still constitute factual documents, our attention now turns to the conditions of their realisation. In what contexts could they have been made, and what do they show us, apart from the very fact that they were produced in an exceptional way?

James album

The history of photography in Pueblo territory, in the United States, offers a rare example of strong reaction to the invasion of photography. The first reactions of mistrust from the Indian communities, from the 1890s, are linked to the dissemination of images and the tourist promotion of rituals supposed remain secret. The Hopi Snake Dance ceremony had become a major attraction. Often disrupted by ever-increasing numbers of visitors, it will be definitively prohibited to photographers in 1913, following the mobilisations of Hopi communities. The exhibition does not present here the photographs of this ritual that George Wharton James manages to capture, in order respect the Hopi restrictions. The exposed double page combines two times of shooting, the first image showing the perplexed waiting of the Indians in front the church of Acoma, and the second their reaction of just surprise and mistrust after shooting.

Text from the exhibition

F. Bonfils et Cie (French, 1831-1885)

Egyptian mummy, Medinet-Abou, Egypt

Cairo, 1870

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

Félix Adrien Bonfils was a French photographer and writer who was active in the Middle East. He was one of the first commercial photographers to produce images of the Middle East on a large scale and amongst the first to employ a new method of colour photography, developed in 1880. …

Maison Bonfils produced thousands of photographs of the Middle East. Bonfils worked with both his wife and his son. Their studio became “F. Bonfils et Cie” in 1878. They photographed landscapes, portraits, posed scenes with subjects dressed up in Middle Eastern regalia, and also stories from the Bible. Bonfils took photographs in Lebanon, Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Greece and Constantinople (now Istanbul). While Bonfils produced the vast majority of his work, his wife, Lydie, and son Adrien were also involved in photography produced by the studio. As few are signed, it is difficult to identify who is responsible for individual photographs. Lydie is thought to have taken some of the studio portraits, especially those of Middle Eastern women, who were more inclined to pose for a female photographer. Adrien became more involved in the landscape photography at age 17, when Félix returned to Alès to have compiled collections of their photographs published and then to open a collotype printing factory. Félix died in Alès on the 9th of April 1855.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Charles Guillain (French, 1808-1875)

Majeerteen Woman

East Coast of Africa, 1847-1848

Daguerreotype

Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Image: Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

As Christine Barthe observes, “In the first ten years of photography, from 1841 to 1851, many travelers would try their hands at daguerreotypes outside Europe. Guillain’s photographs, taken in very difficult conditions, are not always perfect from a technical point of view, but they nevertheless represent the pioneering works in the history of photography.” They offer extraordinary insight into the people, the policies, and the places along the east coast of Africa during the mid nineteenth-century.

Erin Rushing. “Swahili Coast: Exploration by French Captain Charles Guillain, 1846-1848. Part 3, Encounters and Partnerships,” on the Smithsonian Unbound blog May 13, 2015 [Online] Cited 22/05/2023

Ernest Benecke (German born England, 1817-1894)

Dead crocodile on a boat on the Nile

Egypt, 1852

Salt paper print

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Manuscripts Department

Émile Prisse d’Avennes Egyptian Collection

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Ernest Philipp Benecke may have been part of a well-known German banking family of the same name from the Hamburg and Hanover area. Benecke made his only known photographs in Egypt and Nubia in 1852, which consisted of portraits and studies of the daily life of the cultures he visited. His works are among the earliest surviving photographs of non-Western civilizations.

Muhammad Sadiq Bey (Egyptian, 1822-1902)

View of the Holy Shrine and the City of Mecca

Saudi Arabia, 1881

Photographic print

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Rare Books Reserve

© Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Muhammad Sadiq Bey

Muhammad Sadiq Bey (1832-1902) was an Ottoman Egyptian army engineer and surveyor who served as treasurer of the Hajj pilgrim caravan. As a photographer and author, he documented the holy sites of Islam at Mecca and Medina, taking the first ever photographs in what is now Saudi Arabia. …

Born in Cairo, Sadiq was educated in Cairo’s military college and at the Paris École Polytechnique. He qualified as an colonel in the Egyptian army and returned to the military college to teach cartographic drawing.

In 1861, he was assigned to visit the region of Arabia from Medina to the port of Al Wajh and conduct a detailed survey. He took a small team and some surveying equipment as well as his own camera; photography was not part of the official mission. His records of the expedition are the earliest known detailed accounts of the region’s climate and settlements. His photographs of Medina were the first ever taken there. In 1880 he was assigned to accompany the Hajj pilgrim caravan from Egypt to Mecca as its treasurer. He was responsible for the safe passage of the mahmal, a ceremonial passenger-less litter, to Mecca. Again he brought a camera, becoming the first person to photograph Mecca, the Great Mosque, the Kaaba, and pilgrim camps at Mina and Arafat. …

Sadiq used a wet-plate collodion camera, which had been invented in the 1850s. This produced negatives on wet glass plates, requiring a portable darkroom. From these negatives he made albumen prints which he signed or, later, stamped.

The sanctuaries of Mecca and Medina are the holiest sites of Islam. As part of the Hajj which is one of the five pillars of Islam, pilgrims perform rituals at Mecca and other nearby sites. On his expeditions from 1861 to 1881, Sadiq photographed the interiors and exteriors of sites on the Hajj pilgrimage route as well as at Medina. Photographing the Al-Masjid an-Nabawi (Prophet’s Mosque) and its surroundings in Medina on 11 February 1861, he noted in his diary that no-one had taken such photographs before.

He used walls and mosque roofs as vantage points to capture panoramas of the cities. He also photographed people connected to the holy sites. As well as the Hajj pilgrims walking around the Kaaba, he photographed Shaykh ‘Umar al-Shaibi, the keeper of the key of the Kaaba, and Sharif Shawkat Pasha, guardian of the Prophet’s Mosque.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Jules Borelli (French, 1853-1941)

Portrait of a young woman, Ethiopia

1885-1888

Photo: © Dist. RMN – Grand Palais/musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Jules Borelli

Jules Borelli (b. 1853, d. 1941) was a French traveller and explorer who travelled to Ethiopia from Egypt on 16 September 1885 to explore the Omo river. In this effort he was supported by his brother, a financier in Cairo and the owner of a fine collection of Egyptian antiquities. He was delayed from moving into western and southwestern Ethiopia by ase Ménilék II, who, out of political concerns, detained him at the capital of Éntotto for part of the period from July 1886 to November 1887. Finally, in November 1887. Borelli started out for the headwaters of the Omo river, and reached a point some 300 miles north of Lake Rudolf (Turkana) on 17 June 1888, three months after Count Samuel Teleki von Szek and Lieutenant Ludwig Ritter von Hohnel had arrived on the lake’s southern shore. Had Ménilék not detained him and had he not fallen ill with malaria, Borelli could have reached the lake well before Teleki and von Hohnel. During his travels, Borelli was given a good description of the lake by people in Ethiopia, who called it Lake Šambara.

Borelli arrived in Cairo on 15 November 1888, where he later met Teleki and von Hohnel who were returning to Europe from their trip. The latter assisted B. in drawing his maps of the country surrounding the Omo river. Borelli doubted von Hohnel’s unsubstantiated claim that two rivers flowed into Lake Rudolf, and, as was later proven, correctly deduced that only the Omo flowed into the lake. In 1889, Borelli invited von Hohnel to Paris to attend an international geographical congress, where both men lectured. Borelli described his Ethiopian travels in his beautifully illustrated and well documented book published in 1890.

Text from Encyclopaedia Aethiopica

Jules Borelli (French, 1853-1941)

Portrait of a young woman, Ethiopia (detail)

1885-1888

Photo: © Dist. RMN – Grand Palais/musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Unknown photographer

Malay Interior

Nd

Photo: musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN – Grand Palais image musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Isidore Van Kinsbergen (Dutch-Belgian, 1821-1905)

Baris, Warrior dancers Bali

Indonesia, 1865-1866

Albumen print

Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Image: Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Isidore van Kinsbergen (Bruges 1821-Batavia 1905) was a Dutch-Belgian engraver, who after an educational period in Bruges and Gent discovered the artistic wealth of the theatre. In Batavia (Jakarta) he proved to be a real all-rounder, combining decoration painting with singing, acting and management. In 1855, Van Kinsbergen also took up photography. He was invited to photograph ‘all peculiarities’ on the Dutch mission to Bangkok in 1862 and took part in two inspection tours covering Java, Madura and Bali (1862 and 1865). Between 1863 and 1867 and again in 1873 he was contracted by the Government of the Netherlands-Indies to photograph Java’s antiquities. Two series, together holding over 375 photos, constitute his art and archaeology legacy.

There is a less or even ‘unknown’ Van Kinsbergen as well, who commercially operated from a professional studio in Batavia. Thanks to research, more than 200 anonymous or wrongly attributed photos can now be assigned to him. How to recognize Van Kinsbergen in portraits, landscapes, views and ‘types’? After all, making a portrait or casting a ‘type’ is quite different from photographing monuments. Are characteristics found within his art and archaeology series evident in his so-called commercial work? Yes, but not in one stereotypical way. Besides a general artistic rendering of items and the careful use of light, his style is direct, full of contrast, academic and theatrical at the same time.

Gerda Theuns de Boer. “Isidore van Kinsbergen: photographs of Java and Bali, 1855-1880,” on the International Institute for Asian Studies website Newsletter #35 June 2005 [Online] Cited 21/05/2023

Isidore van Kingsbergen (1821-1905) is sometimes described as the “sleeping beauty” of nineteenth-century photography, because his remarkable body of work has never been presented in its entirety. Yet he was a flamboyant artist who appeals to the imagination. For the first time, this publication gives a broad overview of the exceptional qualities of this photo pioneer. Van Kinsbergen became famous for the almost four hundred photographs he took of Java’s antiquities at the behest of the Dutch colonial government and the Batavian Society. Detailed research has also brought to light a hitherto unknown part of his oeuvre, including the portraits he made at the courts of Yogyakarta, Surakarta, Bandung, Madura and Buleleng (Bali). In his studio, he used his experience as a theatre director to photograph people from various social backgrounds in an expressive manner. Due to his tireless efforts for new cultural projects, he has also been called as the “soul of colonial artistic life in Batavia.”

Text from the Brill website

Unknown photographer

Album of photographs of the Philippines

Nd

Photo: musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN – Grand Palais image musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Eugene Maunoury (French, 1830-1896)

Hitoro, King of the island Ua Pou in the Marquesas Archipelago

Peru, 1863

Albumen paper print

© Quai Branly Museum – Jacques Chirac

The text on the photo stating that this man is from Papua New Guinea is incorrect. He is from the Marquesas archipelago. Please see another photograph of Hitoro, King of the island Ua Pou by Eugene Maunoury on the Ua Pou Wikipedia entry.

Eugene Maunoury

Eugène Maunoury settled in Chile between 1858 and 1865, in Santiago and Valparaiso. Then, from 1861, he was at the head of a luxurious studio in Lima (Peru) which saw parade the elite of society. From 1862 he was a correspondent for the Nadar studio. However, these portraits of Marquesans taken in Peru are neither intended images exotic, or photographs intended for scientific use. They were made by Maunoury to protest against the kidnapping of these people intended for be employed in forced labor in the exploitation of guano, in Peru. Maunoury publishes in L’Illustration of August 29, 1863 an article denouncing the situation of the raid, using some of his portraits. We recognise the king of the island Ua Pou, in the Marquesas Archipelago.

Émile Colpaërt (French born 1830 – died after 1874, active 1858-1870)

Native of Urcos

Scientific Expedition, Peru, 1864

© Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais

Image: Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

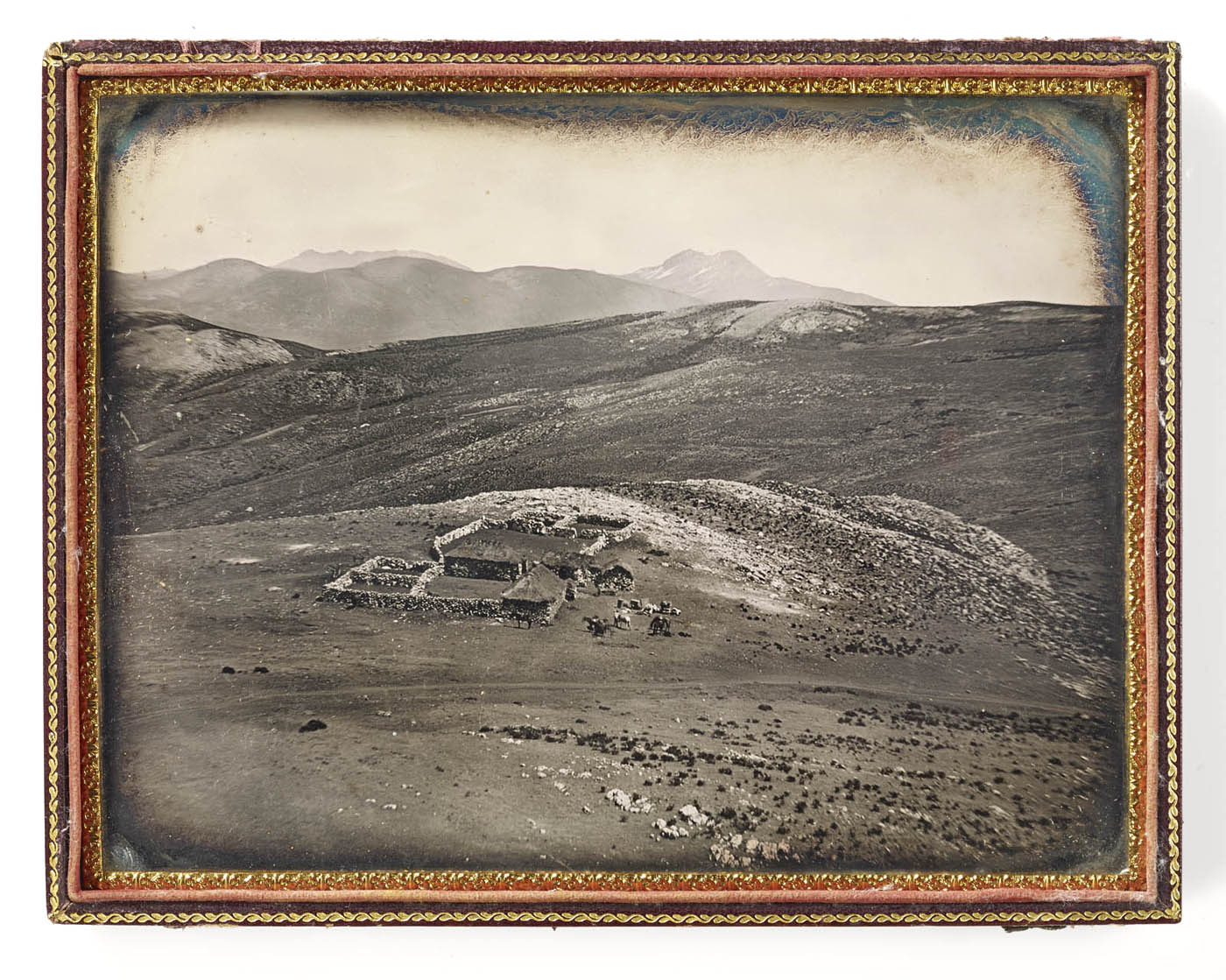

Attributed to Robert H. Vance (American, 1825-1876)

A Tambo in the Mountains at a Height of 16,000 Feet, Andes Mountains

1849

Daguerreotype

RMN – Grand Palais image musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Photo: © musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist

Attributed to Robert H. Vance (American, 1825-1876)

A Tambo in the Mountains at a Height of 16,000 Feet, Andes Mountains (detail)

1849

Daguerreotype

RMN – Grand Palais image musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Photo: © musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist

Paul-Émile Miot (French, 1827-1900)

Portrait of three Mi’kmaq Women, Newfoundland

1857

Image: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Paul-Émile Miot (French, 1827-1900)

Matelots virant au Cabestan, Gaillard d’avant de l’Ardent, Terre Neuve (Sailors tacking to Capstan, forecastle of the Ardent, Newfoundland)

1857

Albumen print

6 1/2 x 10 in.

© musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, Dist