Exhibition dates: 3rd February – 19th April 2009

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Triptych inspired by T.S. Eliot’s ‘Sweeney Agonistes’

1967

Oil on canvas

198 x 147.5cm (each)

Washington, D.C. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution. Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1972

Looks like an amazing exhibition of Francis Bacon’s work, one of my favourite artists – I wish I could see it!

.

Many thankx to the Museo Nacional del Prado for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The exhibition is constructed in different sections

- Animal

- Zone

- Apprehension

- Crucifixion

- Crisis

- Archive

- Portrait

- Memorial

- Epic

- Late

.

Bacon’s work demonstrates marked similarities to that of many of the Spanish artists he admired. (Manuela Mena, co-curator of the exhibition at the Prado, has written an excellent essay on this topic that can be found in the exhibition’s catalog.) The retrospective at the Prado provides a rare opportunity to compare Bacon to some of the Spanish masters that influenced him.

Start by meandering through the vast Bacon exhibition. Spread between two floors of the new wing of the Prado, the exhibition has brought together Bacon’s most important works from nearly his entire artistic production. It begins with the work that put Bacon on the map, “Three Studies for Figures at the Foot of a Crucifixion” (1944), and follows his work through the interpretations of Velázquez, crucifixion triptychs, his unique portraits and the late works through the years shortly before his death.

Text from the Prado website

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion

c. 1944

Oil on board

94 x 73.7cm

London, Tate, presented by Eric Hall 1953

Animal

A philosophical attitude to human nature first emerges in Francis Bacon’s works of the 1940s. They reflect his belief that, without God, humans are subject to the same natural urges of violence, lust and fear as any other animal. He showed Figure in a Landscape and Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion in April 1945, and exhibited consistently thereafter. The bestial depiction of the human figure was combined with specific references to recent history and especially the devastating events of the Second World War. Bacon often drew his inspiration from reproductions, acquiring a large collection of books, catalogues and magazines. He repeatedly studied key images in order to probe beneath the surface appearance captured in photographs. Early concerns that would persist throughout his work include the male nude, which reveals the frailty of the human figure, and the scream or cry that expresses repressed and violent anxieties. These works are among the first in which he sought to balance psychological insights with the physical identity of flesh and paint.

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X

1953

Oil on canvas

153 x 118cm

Des Moines, Nathan Emory Coffin Collection of the Des Moines Arts Center, purchased with funds from the Coffin Fine Arts Trust

Zone

In his paintings from the early 1950s, Bacon engaged in complex experiments with pictorial space. He started to depict specific details in the backgrounds of these works and created a nuanced interaction between subject and setting. Figures are boxed into cage-like structures, delineated ‘space-frames’ and hexagonal ground planes, confining them within a tense psychological zone. In 1952 he described this as “opening up areas of feeling rather than merely an illustration of an object”. Through his technique of ‘shuttering’ with vertical lines of paint that merge the foreground and background, Bacon held the figure and the setting together within the picture surface, with neither taking precedence in what he called “an attempt to lift the image outside of its natural environment”.

A theme that emerged in the 1950s was the extended series of variants of Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1650 (Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj), a work Bacon knew only from illustrations. He used this source to expose the insecurities of the powerful – represented most often in the scream of the caged figure. Through the open mouth Bacon exposed the tension between the interior space of the body and the spaces of its location, which is explored more explicitly in the vulnerability of the ape-like nudes.

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Chimpanzee

1955

Oil on canvas

152.5 x 117cm

Stuttgart, Staatsgalerie

Apprehension

Implicit throughout Bacon’s work of the mid 1950s is a sense of dread pervading the brutality of everyday life. Not only a result of Cold War anxiety, this seems to have reflected a sense of menace at a personal level emanating from Bacon’s chaotic affair with Peter Lacy (who was prone to drunken violence) and the wider pressures associated with the continuing illegality of homosexuality. The Man in Blue series captures this atmosphere, concentrating on a single anonymous male figure in a dark suit sitting at a table or bar counter on a deep blue-black ground. Within their simple painted frames, these awkwardly posed figures appear pathetically isolated.

Bacon’s interest in situations that combine banality with acute apprehension was also evident in other contemporary works. From figures of anxious authority, his popes took on malevolent attributes and physical distortions that were directly echoed in the paintings of animals, whose actions are also both sinister and undignified. Some of these images derived from Bacon’s close scrutiny of the sequential photographs of animals and humans taken by Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), which he called “a dictionary” of the body in motion.

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Three Studies for a Crucifixion

1962

Oil on canvas

198.2 x 144.8cm

New York, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

Crucifixion

Bacon made paintings related to the Crucifixion at pivotal moments in his career, which is why these key works are gathered here. The paradox of an atheist choosing a subject laden with Christian significance was not lost on Bacon, but he claimed, “as a non-believer, it was just an act of man’s behaviour”. Here the instincts of brutality and fear combine with a deep fascination with the ritual of sacrifice. Bacon had already made a very individual crucifixion image in 1933 before returning to the subject with his break-through triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion in 1944. This is a key precursor to later themes and compositions, containing the bestial distortion of human figures within the triptych format. These monstrous creatures displace the traditional saints and Bacon later related them to the Eumenides – the vengeful furies in Greek mythology. In resuming the theme in the 1960s, especially in 1962 as the culmination of his first Tate exhibition, Bacon used references to Cimabue’s 1272-1274 Crucifixion to introduce a more explicitly violent vision. Speaking after completing the third triptych in 1965 he simply stated: “Well, of course, we are meat, we are potential carcasses”.

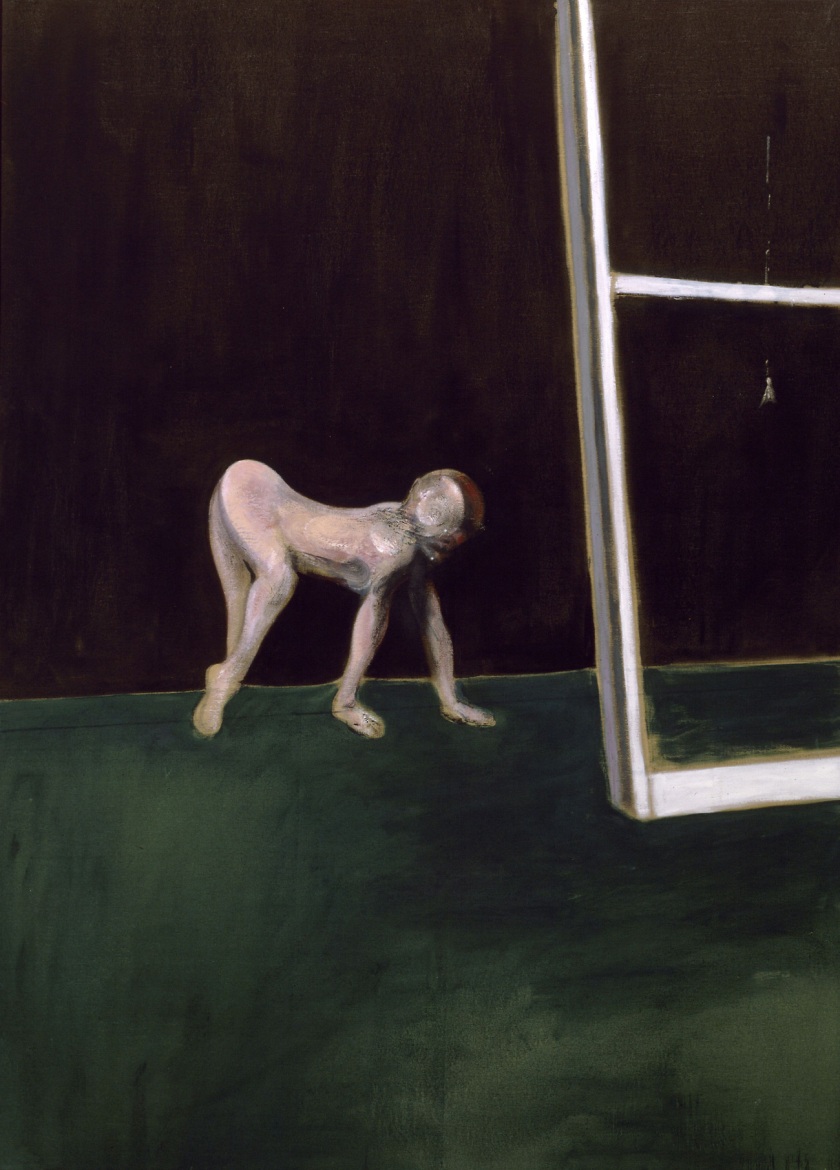

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Paralytic Child Walking on All Fours (from Muybridge)

1961

Oil on canvas

198 x 142cm

The Hague, Collection Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Crisis

Between 1956 and 1961, Bacon travelled widely. He spent time in places marginal to the art world, in Monaco, the South of France and Africa, and particularly with Peter Lacy in the ex-patriot community in Tangier. In this rather unsettled context, he explored new methods of production, shifting to thicker paint, violently applied and so strong in colour as to indicate an engagement with the light of North Africa. This was most extreme in his series based on a self-portrait of Van Gogh, The Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888, destroyed), which became an emblem of the modern predicament. Despite initial acclaim, Bacon’s Van Gogh works were soon criticised for their “reckless energy” and came to be viewed as an aberration. They can now be recognised as pivotal to Bacon’s further development, however, and allow glimpses into his search for new ways of working. His innovations were perhaps in response to American Abstract Expressionism, of which he was publicly critical. Although he eventually returned to a more controlled approach to painting, the introduction of chance and the new vibrancy of colour at this moment would remain through out his career.

Montage of material from Bacon’s Studio (including pictures of Velázquez’s Innocent X, The Thinker by Rodin etc.)

7 Cromwell Place

c. 1950

© Sam Hunter

Archive

The posthumous investigation of Bacon’s studio confirmed the extent to which he used and manipulated photographic imagery. This practice was already known from montages recorded in 1950 by the critic Sam Hunter. Often united by a theme of violence, the material ranges between images of conflict, big game, athletes, film stills and works of art.

An important revelation that followed the artist’s death was the discovery of lists of potential subjects and preparatory drawings, which Bacon had denied making. Throughout his life, he asserted the spontaneous nature of his work, but these materials reveal that chance was underpinned by planning.

Photography offered Bacon a dictionary of poses. Though he most frequently referred to Eadweard Muybridge’s (1830-1904) survey of human and animal locomotion, images of which he combined with the figures of Michelangelo, he remained alert to photographs of the body in a variety of positions.

A further extension of Bacon’s preparatory practices can be seen in his commissioning of photographs of his circle of friends from the photographer John Deakin (1912-1972). The results – together with self-portraits, photo booth strips, and his own photographs – became important prompts in his shift from generic representations of the human body to portrayals of specific individuals.

A matrix of images

Bacon’s use of photographic sources has been known since 1950 when the critic Sam Hunter took three photographs of material he had selected from a table in Bacon’s studio in Cromwell Place, South Kensington. Hunter observed that the diverse imagery was linked by violence, and this fascination continued throughout Bacon’s life. Images of Nazis and the North African wars of the 1950s were prominent in his large collection of sources. Films stills and reproductions of works of art, including Bacon’s own, were also common. The dismantling of Bacon’s later studio, nearby at Reece Mews, after his death confirmed that the amassing of photographic material had remained an obsession. While some images were used to generate paintings, he also seems to have collected such an archive for its own sake.

The mediated image

From the 1960s, Bacon’s accumulation of chance images began to include a more deliberate strategy of using photographs of his close circle. They became key images for the development of the portraits that dominated his paintings at this time. Snap shots and photo booth strips were augmented by the unflinching photographs taken by his friend John Deakin. Bacon specifically commissioned some of these from Deakin as records of those close to him – notably his partner from 1962, George Dyer – and they served as sources for likenesses and for poses for the rest of his career.

The Physical Body

Bacon drew more from Eadweard Muybridge’s sequential photographs of human and animal locomotion than from any other source. These isolated the naked figure in a way he clearly found stimulating. He also, however, spoke of projecting on to them Michelangelo’s figures which for him had more “ampleness” and “grandeur of form”.

His fascination in photography’s freezing of the body in motion led him to collect sports photographs, particularly boxing, cricket and bullfighting. It was not just movement but the physicality of the body that Bacon scrutinised, using found images to provoke new ways of picturing its strength and vulnerability.

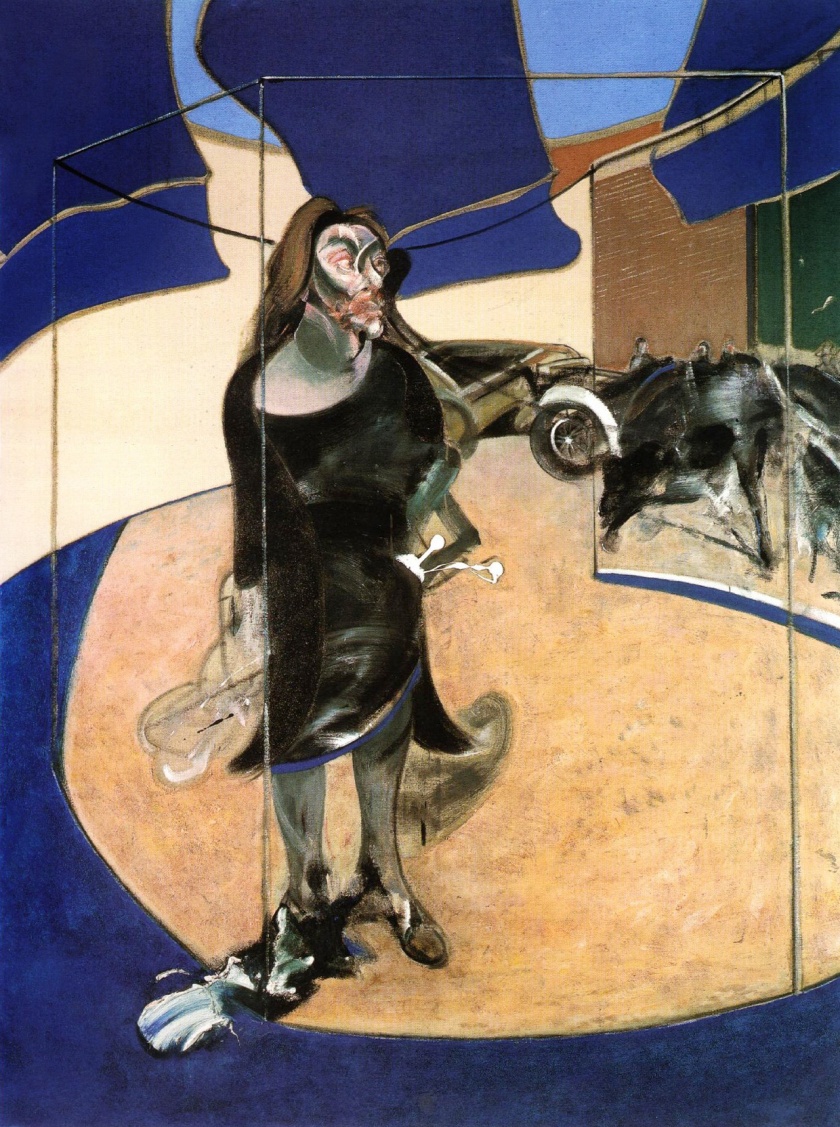

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Portrait of Isabel Rawsthorne Standing in a Street in Soho

1967

Oil on canvas

198 x 147.5cm

Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie

Portrait

During the 1960s, the larger part of Bacon’s work shifted focus to portraits and paintings of his close friends. These works centre on two broad concerns: the portrayal of the human condition and the struggle to reinvent portraiture. Bacon drew upon the lessons of Van Gogh and Velázquez, but attempted to rework their projects for a post-photographic world. His approach was to distort appearance in order to reach a deeper truth about his subjects. To this end, Bacon’s models can be seen performing different roles. In the Lying Figures series, Henrietta Moraes is naked and exposed. This unprecedented raw sexuality reinforces Bacon’s understanding of the human body simply as meat. By contrast Isabel Rawsthorne, a fellow painter, always appears in control of how she is presented. With a mixture of contempt and affection, Bacon depicted George Dyer, his lover and most frequent model, as fragile and pathetic. This is especially evident in Dyer’s first appearance in Bacon’s work, in Three Figures in a Room, in which he represents the absurdities, indignities and pathos of human existence. Everyday objects occasionally feature in these works, hollow props for lonely individuals which reinforce the sense of isolation that Bacon associated with the human condition.

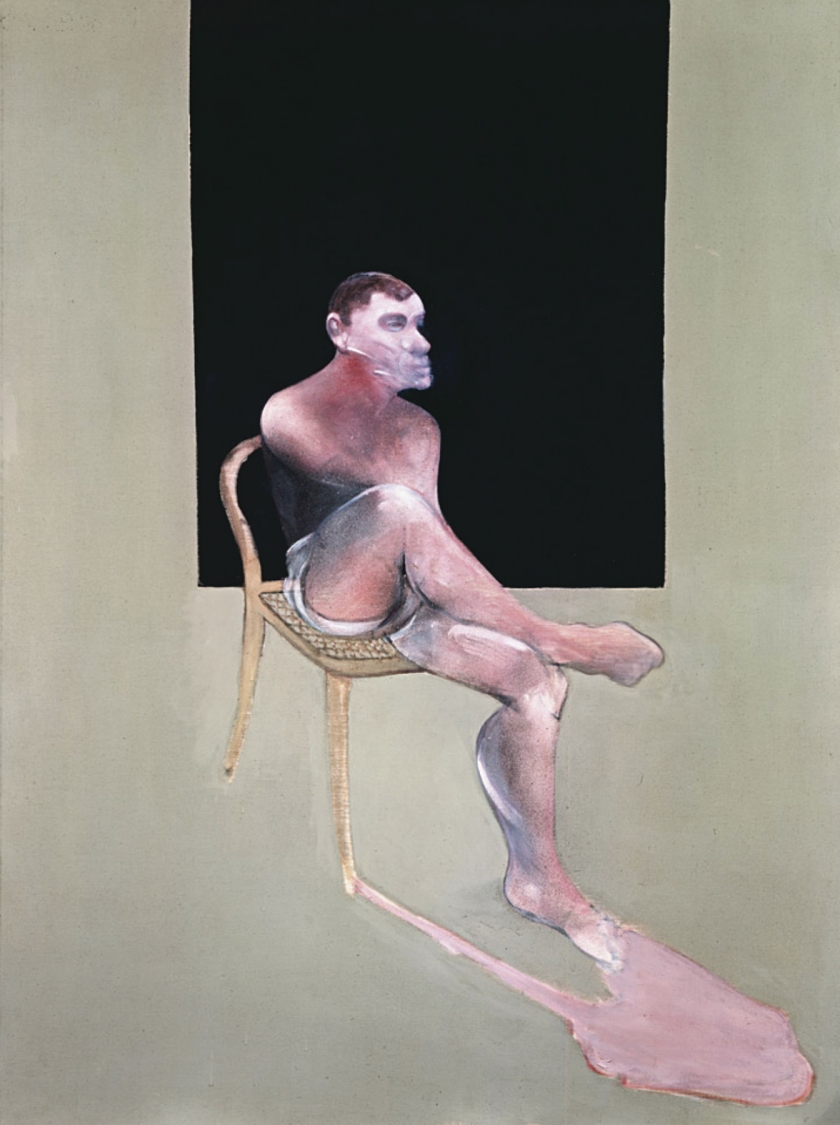

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Triptych – August 1972

1972

Oil on canvas

198 x 147.5cm

London, Tate

Memorial

This room is dedicated to George Dyer who was Bacon’s most important and constant companion and model from the autumn of 1963. He committed suicide on 24 October 1971, two days before the opening of Bacon’s major exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris. Influenced by loss and guilt, the painter made a number of pictures in memorial to Dyer. From this period onwards the large-scale triptych was his established means for major statements, having the advantage of simultaneously isolating and juxtaposing the participating figures, as well as guarding against narrative qualities that Bacon strove to avoid. But while evading narrative, Bacon drew more than ever from literary imagery; the first of the sequence, Triptych In Memory of George Dyer 1971, refers to a specific section of T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922). In addition to his own memory, for Triptych – August 1972 Bacon relied on photographs, taken by John Deakin, of Dyer in various poses on a chair. He confined his dense and energetic application of paint to the figures in these works. The dark openings consciously evoke the abyss of mortality that would become a recurring concern in Bacon’s later works.

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Triptych

1987

Oil on canvas

198 x 147.5cm

London, The Estate of Francis Bacon, courtesy Faggionato Fine Art

Epic

References to poetry and drama became a central element in Bacon’s work from the second half of the 1960s. Alongside images of friends and single figures (often self-portraits), he produced a series of grand works that identified with great literature. Imbued with the inevitability and constant presence of death, the poetry of T.S. Eliot was a particular source of inspiration. The sentiments of the poet’s character Sweeney could be said to echo the painter’s perspective on life:

Birth, and copulation, and death.

That’s all the facts when you come to

brass tacks:

Birth, and copulation, and death.

The works in this room refer to and derive from literature. Some make direct references in their titles, others depict, sometimes abstractly, a certain scene or atmosphere within the narratives themselves. Bacon repeatedly stated that none of his paintings were intended as narratives, so rather than illustrations, these works should perhaps be understood as evoking the experience of reading of Eliot’s poetry or Aeschylus’s tragedies: their violence, threat or erotic charge. Thus, of the triptych created after reading Aeschylus, Bacon explained “I tried to create images of the sensations that some of the episodes created inside me”.

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Portrait of John Edwards

1988

Oil on canvas

198 x 147.5cm

The Estate of Francis Bacon, courtesy of Faggionato Fine Arts, London, and Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York

Late

When Bacon turned seventy in 1979, more than a decade of work lay ahead of him. Neither his legendarily hedonistic lifestyle nor his work pattern seemed to age him, but he was continually facing up to mortality through the deaths of those around him. This unswerving confrontation, however mitigated by youthful companions such as John Edwards, became the great theme of his late style. Constantly stimulated by new source material – for example the photographs and the poetry of Federico García Lorca which triggered his bullfight paintings – he was able to adapt them to his abiding concerns with the vulnerability of flesh. Exploring new techniques he also extended his fascination with how appropriate oil paint is for rendering the human body’s sensuality and sensitivity. A certain despairing energy may also be felt in the forceful throwing of paint that dominates some of these final works: the controlled chance as a defiant gesture. Ultimately, and appropriately, Bacon’s last triptych of 1991 returns to the key image of sexual struggle that had frequently recurred in his work. He faced death with a defiant concentration on the exquisiteness of the lived moment.

Francis Bacon (British, 1909-1992)

Three Studies for Self-Portrait

1979-1980

Oil on canvas

37.5 x 31.8cm

Nueva York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Jacques and Natasha Gelman collection, 1998

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon is internationally acknowledged as among the most powerful painters of the twentieth century. His vision of the world was unflinching and entirely individual, encompassing images of sensuality and brutality, both immediate and timeless. When he first emerged to public recognition, in the aftermath of the Second World War, his paintings were greeted with horror. Shock has since been joined by a wide appreciation of Bacon’s ability to expose humanity’s frailties and drives.

This major retrospective gathers many of his most remarkable paintings and is arranged broadly chronologically. Bacon’s vision of the world has had a profound impact. It is born of a direct engagement that his paintings demand of each of us, so that, as he famously claimed, the “paint comes across directly onto the nervous system”.

As an atheist, Bacon sought to express what it was to live in a world without God or afterlife. By setting sensual abandon and physical compulsion against hopelessness and irrationality, he showed the human as simply another animal. As a response to the challenge that photography posed for painting, he developed a unique realism which could convey more about the state of existence than photography’s representation of the perceived world. In an era dominated by abstract art, he amassed and drew upon a vast array of visual imagery, including past art, photography and film. These artistic and philosophical concerns run like a spine through the present exhibition.

Museo Nacional Del Prado

Paseo del Prado, s/n,

28014 Madrid, Spain

Opening hours:

Monday – Saturday 10am – 8pm

Sunday 10am – 7pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.