Exhibition dates: 24th October 2015 – 14th February 2016

Entrance to the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

I was lucky enough to be up in Sydney to review the Julia Margaret Cameron exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales… and the media preview for The Greats was on. What an unexpected bonus!

This is part 1 of a monster 2 part posting on the exhibition which, in all honesty, is a bit of a hotchpotch of a blockbuster. But my god, what a hotchpotch it is.

Highlights in part 1 of the posting include:

~ The vibrancy and folds of the pink dress of the Virgin as it flows down and under the Christ child in Botticelli’s The Virgin adoring the sleeping Christ child, c. 1485

~ The stillness and intensity, colouration of the figures in Johannes Vermeer’s Christ in the house of Martha and Mary, c. 1654-1655

~ The glorious “atmosphere”, light and colour in Jan Lievens’ Young man in yellow c. 1630-1631, one of the unexpected highlights of the exhibition

~ The intensity of the painting, the precision and care in Diego Velazquez’s An old woman cooking eggs 1618. Now that is really looking at the world

~ And the glorious frames of all these works. I do like a good frame!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the AGNSW for allowing me to publish the art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All installation photographs © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Installation photographs of Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) (Italian, c. 1485/90-1576) Venus rising from the sea (Venus Anadyomene) (c. 1520-25)

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) (Italian, c. 1485/90-1576)

Venus rising from the sea (Venus Anadyomene)

c. 1520-1525

Oil on canvas

74 x 56.2cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Titian was the most celebrated Venetian painter of his time. His wealthy and learned patrons spanned across Europe. Well-versed in classical art and literature, including the myths of ancient Greece and Rome, they fuelled a strong demand for paintings like Venus rising from the sea c. 1520-1525. According to legend, Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, was born fully grown from the sea. She was then carried to land upon a scallop shell, blown by the zephyr winds.

In Venus rising from the sea, Titian has painted the goddess as a beautiful and voluptuous woman, emerging from the sea and wringing out her wet hair, with a miniature version of her scallop shell floating nearby. Her long auburn locks, milky skin and blushing cheeks are sensuous and tactile, suggesting her seductive powers as the goddess of love. Venus’s gracious, twisting pose recalls classical statues of the goddess. Titian rarely made preparatory drawings for his paintings, preferring to work straight onto the canvas, applying subtle gradations of colour in soft, feathery brushstrokes. He also used live models to pose for his figures, which was uncommon in the early 1500s. This lends the painting its great liveliness and sensuality – qualities that have made Titian justly famous.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444/45-1510)

The Virgin adoring the sleeping Christ child (‘The Wemyss Madonna’) (installation views)

c. 1485

Tempera, oil and gold on canvas

122 x 80.5cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444/45-1510)

The Virgin adoring the sleeping Christ child (‘The Wemyss Madonna’) (installation details)

c. 1485

Tempera, oil and gold on canvas

122 x 80.5cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Painted by one of the most outstanding artists of the Italian Renaissance, The Virgin adoring the sleeping Christ child c. 1485 is the earliest work in the exhibition. It has not left the United Kingdom since 1846 and The Greats presents the first time in almost three decades that any painting by Botticelli has been exhibited in Sydney. In this devotional painting, the Virgin Mary kneels silently and prays before her son, the infant Jesus Christ, in a rose-filled garden. Her gown and cloak spill onto the ground to provide a pillow for the child, who is nestled among the flowers, asleep. Its simple composition, focusing on just the two figures, invites quiet contemplation.

Like many Renaissance paintings, the picture is rich in symbolism. The enclosed garden is a reference to the purity of the Virgin, who was often called ‘a rose without thorns’. Some symbols are more ominous. The sleeping child with his pallid complexion is presumably a reference to Christ’s eventual death. The red strawberry plant in the lower right corner symbolises the blood he will shed on the cross. Technically the painting is unusual for the Florentine artist: it is quite small and has been painted on canvas rather than wooden panel. This suggests it was intended for a private home or convent, rather than a public space like a church.

Installation view of the exhibition The Greats: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney showing at left, Domenichino’s The adoration of the shepherds (c. 1606-1608)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Domenichino (Domenico Zampieri) (Italy, 1581-1641)

The adoration of the shepherds

c. 1606-1608

Oil on canvas

143 x 115cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Purchased 1971

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Installation view of the exhibition The Greats: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney showing at centre, Sir Anthony van Dyck’s Saint Sebastian bound for martyrdom (c. 1620-1621)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Sir Anthony van Dyck (Southern Netherlands, 1599-1641)

Saint Sebastian bound for martyrdom (installation views)

c. 1620-1621

Oil on canvas

230 x 163.3cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Purchased by the Royal Institution, 1830; transferred, 1859

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Anthony van Dyck, the most successful pupil of Peter Paul Rubens, is regarded as one of the masters of the Flemish baroque. Painted just before Van Dyck left Flanders for Italy in 1621, this dramatic composition features Saint Sebastian, a Roman officer who converted secretly to Christianity. When Sebastian’s faith was discovered, he was tied to a tree and shot with arrows. Usually shown at the moment of his martyrdom, with the arrows piercing his body, here Sebastian has been portrayed prior to his execution. His twisting body and his upward-turned face seem to anticipate the punishment that is to come.

Sir Anthony van Dyck (Southern Netherlands, 1599-1641)

Saint Sebastian bound for martyrdom (installation view details)

c. 1620-1621

Oil on canvas

230 x 163.3cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Purchased by the Royal Institution, 1830; transferred, 1859

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

The Greats: masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland is one of the most significant collections of European old master paintings ever seen in Australia and is presented as part of the Sydney International Art Series 2015-2016. Spanning a period of 400 years from the Renaissance to Impressionism, The Greats includes works by the most outstanding names in Western art, including Botticelli, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian, Rubens, Velázquez, Poussin, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Turner, Monet, Degas, Gauguin, and Cézanne.

This richly presented exhibition brings together over 70 of the greatest paintings and drawings from the National Galleries of Scotland, based in the beautiful capital city of Edinburgh. The Greats marks the first time these artworks have been exhibited in Australia, with the exception of Rembrandt’s A woman in bed (c. 1647) and Seurat’s La Luzerne, Saint-Denis (1884-1885). Botticelli’s Virgin adoring the sleeping Christ child (c. 1485) has not been exhibited outside of the United Kingdom in 169 years.

Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Michael Brand, said it is a tremendous privilege to host such a fine collection of masterpieces in Sydney and that the Art Gallery of NSW is extremely grateful to the National Galleries of Scotland for their generosity and collegiality. “The Greats is a statement of unequivocal artistic excellence – each piece in this exhibition is of extraordinary quality. We are excited to provide Australian audiences the rare opportunity to come face to face with such unique and masterful artworks,” Brand said.

“Approaching the entrance to the Art Gallery of NSW, we are reminded of Sydney’s historic aspirations for viewing the creations of European old masters, with names such as Titian, Rembrandt and Botticelli adorning the Gallery’s sandstone facade. It is with great pleasure that we now welcome incredible works by these artists to our interior walls, into a sublime exhibition space that promises a moving and absorbing experience for all visitors,” Brand added.

Director of the Scottish National Gallery, Michael Clarke, said, “We are delighted to present some of the finest masterworks from the National Galleries of Scotland at the distinguished Art Gallery of New South Wales. The Gallery provides a marvellous venue for our exhibition, which includes a selection of paintings that have recently toured to art institutions in America, including the de Young in San Francisco and the Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth.”

Visitors to The Greats will experience the Scottish National Gallery’s famous interior with part of the exhibition space inspired by the Edinburgh gallery’s octagonal rooms with fabric walls of a sumptuous red – the traditional colour on which to hang old master paintings. This installation will serve to accentuate the grandeur of the paintings and foster an intimate experience with each of the artworks. A variety of associated public and education programs are on offer to visitors of all ages. Serving to engage the widest possible audience, the Gallery will host daily guided tours, lecture series, late night programs and a suite of other events designed to facilitate meaningful interactions with the artworks featured in The Greats.

Press release from the AGNSW

Installation views of the exhibition The Greats: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney showing in the bottom two images, Frans Hals’ Portrait of Pieter(?) Verdonck (c. 1627, left) and Johannes Vermeer’s Christ in the house of Martha and Mary (c. 1654-1655, centre)

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Frans Hals (The Netherlands, 1582/3-1666)

Portrait of Pieter(?) Verdonck (installation view)

c. 1627

Oil on panel

Scottish National Gallery

Presented by John J Moubray of Naemoor, 1916

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

With his loose and seemingly spontaneous brushwork, combined with an exceptional ability to capture a sitter’s likeness and expression, Hals inspired generations of artists, from Jean-Honoré Fragonard to Édouard Manet. This portrait probably shows Pieter Verdonck, a Haarlem Mennonite, who was said to be aggressive and argumentative. In a contemporary engraving after the painting, an inscription reads: ‘This is Verdonck, that outspoken fellow, / whose jawbone attacks everyone.’ The jawbone that he holds is the same weapon used by the biblical hero Samson to kill the Philistines; here, it may refer to Verdonck’s ability to wound his enemies with his cutting words.

Frans Hals (The Netherlands, 1582/3-1666)

Portrait of Pieter(?) Verdonck (installation view)

c. 1627

Oil on panel

Scottish National Gallery

Presented by John J Moubray of Naemoor, 1916

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Johannes Vermeer (The Netherlands, 1632-1675)

Christ in the house of Martha and Mary (installation view)

c. 1654-1655

Oil on canvas

Scottish National Gallery

Presented by the Sons of WA Coats in memory of their father, 1927

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

The fame of Vermeer, now one of the best-known painter of the Dutch Golden Age, rests on just 36 paintings known to survive today. This canvas is music larger than his usual compositions and is the only one that illustrates a biblical subject. In spite of its uniqueness, the painting is replete with the quiet human interactions for which the artist is known. The scene depicts the story from Luke 10:38-42, in which Martha objected to her sister Mary listening to Jesus while she herself was busy serving. Given the substantial size of the canvas, it is likely that the painting was a specific commission, possibly intended for a Catholic church.

Installation view of the exhibition The Greats: Masterpieces from the National Galleries of Scotland at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney showing at centre, Rembrandt van Rijn’s A woman in bed (164(7?)) and at right, Jan Lievens’ Young man in yellow (c. 1630-1631)

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Rembrandt van Rijn (The Netherlands, 1606-1669)

A woman in bed (installation views)

164(7?)

Oil on canvas (formerly laid down on panel)

81.4 x 67.9cm (arched top)

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh Presented by William McEwan, 1892

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

The model for this painting is still unidentified. She might be any one of the three main women in Rembrandt’s life: his wife, Saskia; his son’s nursemaid, Geertje Dircx; or his family’s servant girl, Hendrickje Stoffels. Though intimate in its appearance, the painting is probably not a portrait, as a bed would have been an inappropriate setting for a respectable female model. The figure most likely represents the biblical character Sarah from the Old Testament Book of Tobit. Rembrandt shows her watching anxiously as her bridegroom Tobias chases away the devil that had murdered each of her previous seven husbands on their wedding nights.

Rembrandt van Rijn (The Netherlands, 1606-1669)

A woman in bed (installation view detail)

164(7?)

Oil on canvas (formerly laid down on panel)

81.4 x 67.9cm (arched top)

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh Presented by William McEwan, 1892

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Jan Lievens (The Netherlands, 1607-1674)

Young man in yellow (installation view)

c. 1630-1631

Oil on canvas

112 x 99cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Purchased with the aid of the Cowan Smith Bequest Fund, 1922

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Jan Lievens (The Netherlands, 1607-1674)

Young man in yellow (installation view detail)

c. 1630-1631

Oil on canvas

112 x 99cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Purchased with the aid of the Cowan Smith Bequest Fund, 1922

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Jan Lievens and Rembrandt van Rijn were two young artists working in Leiden in the years around 1630. They worked separately, though they engaged in artistic competition and exchange, as this painting suggests. The dramatically lit depiction of a young man posing as a commander with his gorget and baton is not a true portrait, but a tronie – a Dutch term for a painting that features an exaggerated facial expression or a figure in an almost theatrical costume. Both Lievens and Rembrandt experimented with tronies early in their careers, often introducing members of their families or their own likenesses.

Paolo Veronese (Italy, 1528-1588)

Venus, Cupid and Mars (installation views)

1580s

Oil on canvas

165.2 x 126.5cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Purchased by the Royal Institution, 1859; transferred, 1868

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photos: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Veronese was famous in his lifetime as a master of rich colour. His paintings often show exotic figures, sumptuous fabrics and such seemingly incidental details as the spaniel pictured at lower right. The depiction of a dog, a symbol of marital fidelity, was intended as a clever and ironic commentary on the adulterous relationship between Venus, the goddess of love and wife of Vulcan, and Mars, the god of war. This canvas was presented as a diplomatic gift on behalf of the Spanish Crown to King Charles 1 of Britain during his trip to Spain in 1623.

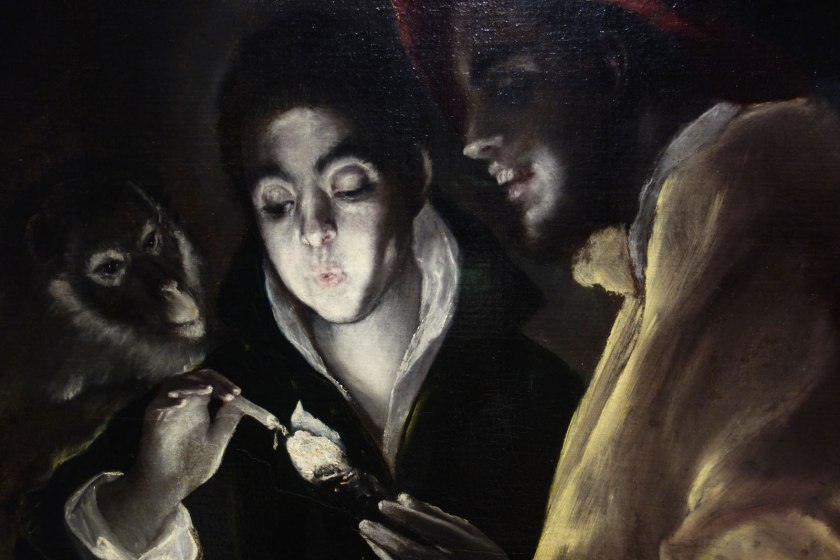

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) (Greece/Spain, 1541-1614)

An allegory (Fábula) (installation view)

c. 1585-1595

Oil on canvas

67.3 x 88.6cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax (hybrid arrangement), with additional funding from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund, and Gallery funds, 1989

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

This enigmatic composition has been described as an allegory to fable (fábula), though its specific meaning has long been debated. One possibility is that it is a recreation of a lost painting of a boy blowing a fire, made by the ancient artist Antiphilus of Alexandria and known from a text written in the 1st century by Pliny the Elder. The presence of the monkey evokes the classical notion of art as the ape of nature, while the man, whose toothy grin and red and yellow attire identify him as a jester, may allude to the ultimate folly of the painter’s aim of reproducing the visible world – or, perhaps, of imitating the ancients.

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) (Greece/Spain, 1541-1614)

An allegory (Fábula) (installation view detail)

c. 1585-1595

Oil on canvas

67.3 x 88.6cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax (hybrid arrangement), with additional funding from the National Heritage Memorial Fund, the Art Fund, and Gallery funds, 1989

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Diego Velazquez (Spain, 1599-1660)

An old woman cooking eggs

1618

Oil on canvas

100.5 x 119.5cm

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Purchased with the aid of the Art Fund and a special Treasury Grant, 1955

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

This simple scene of everyday life in seventeenth-century Spain displays the technical sophistication of painter Diego Velázquez. No Velázquez of comparable importance has been seen before in Australia. And indeed, the painting marks the Scottish National Gallery’s most expensive purchase to date. Painted in 1618 when the artist was just eighteen or nineteen years old, the work depicts an old woman cooking eggs in a red-glazed pot, while a young boy holds a flask of wine and a melon. The subjects were real people, perhaps family members or neighbours, and both reappear in other paintings by the artist. It is likely that Velázquez painted the objects and figures directly from life.

The scene is painted with utmost care and detail. His depiction of light and the textures of objects is meticulous – from the soft folds of the woman’s headscarf, to the thick glaze on a ceramic pot, to the warm sheen of light hitting brass or copper. Unlike other portrayals of everyday people and humble genre scenes, this portrait presents its subjects with dignity, without mockery or censure. The extraordinary skill of Velázquez was considered to be unprecedented in Spain at the time. Establishing himself as much-respected painter in his native Seville, the artist moved to the royal courts of Madrid in 1623 and was soon appointed painter to King Philip IV.

Gerrit Dou (The Netherlands, 1613-1675)

An interior with a young viola player (installation view)

1637

Oil on oak panel

31.1 x 23.7cm (arched top)

Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Purchased with the aid of the National Heritage Memorial Fund 1984

© Trustees of the National Galleries of Scotland

Photo: © Marcus Bunyan and the Art Gallery of New South Wales

Dou was the father of the so-called fijnschilders (fine painters), the Lieden school celebrated for its commitment to detailed illusionism and refined technique. This painting is rendered so precisely that it is possible to identify the open book, shown at centre, as De Friesche Lust-Hof (The Frisian pleasure garden), a popular Dutch songbook first published in 1621. The pages are turned to a comic number about the joys and sorrows of love, accompanied by an image of two lovers under a tree in a landscape. For the informed viewer, this depiction adds unexpected irony to the tranquil, melancholic portrayal of the young musician.

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery Road, The Domain

Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Opening hours:

Open every day 10am – 5pm

except Christmas Day and Good Friday

You must be logged in to post a comment.