February 2014

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Trailer from All This Can Happen

2012

“The highest and the lowest, the most serious and the most hilarious things are to the walker equally beloved, beautiful and valuable…”

Dislocation

Displacement

Discontinuity

Death

Dance

Despair

Documentary

Scene

Seen

Single

Multiple

Surreal

Mundane

Storyline

Sound

Subject

Space

Encounters

Engagements

Negotiations

Time

Memory

Location

Voice

Touch

Walking

Flaneur

Body

Soul

Life itself!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

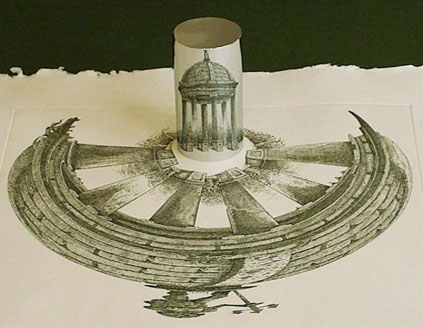

Created by Siobhan Davies and filmmaker David Hinton in 2012, All This Can Happen is a film constructed entirely from archive photographs and footage from the earliest days of cinema.

Based on Robert Walser’s novella The Walk (1917), the film follows the footsteps of the protagonist as series of small adventures and chance encounters take the walker from idiosyncratic observations of ordinary events towards a deeper pondering on the comedy, heartbreak and ceaseless variety of life. A flickering dance of intriguing imagery brings to light the possibilities of ordinary movements from the everyday which appear, evolve and freeze before your eyes. Juxtapositions, different speeds and split frame techniques convey the walker’s state of mind as he encounters a world of hilarity, despair and ceaseless variety.

“To walk in the city is to experience the disjuncture of partial vision/partial consciousness. The narrativity of this walking is belied by a simultaneity we know and yet cannot experience. As we turn a corner, our object disappears around the next corner. The sides of the street conspire against us; each attention suppresses a field of possibilities. The discourse of the city is a syncretic discourse, political in its untranslatability. Hence the language of the state elides. Unable to speak all the city’s languages, unable to speak all at once, the state’s language become monumental, the silence of headquarters, the silence of the bank. In this transcendent and anonymous silence is the miming of corporate relations. Between the night workers and the day workers lies the interface of light; in the rotating shift, the disembodiment of lived time. The walkers of the city travel at different speeds, their steps like handwriting of a personal mobility. In the milling of the crowd is the choking of class relations, the interruption of speed, and the machine. Hence the barbarism of police on horses, the sudden terror of the risen animal.”

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993, p. 2. Prologue.

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Alice in Wonderland

2012

Still from All This Can Happen

Courtesy of BFI National Archive

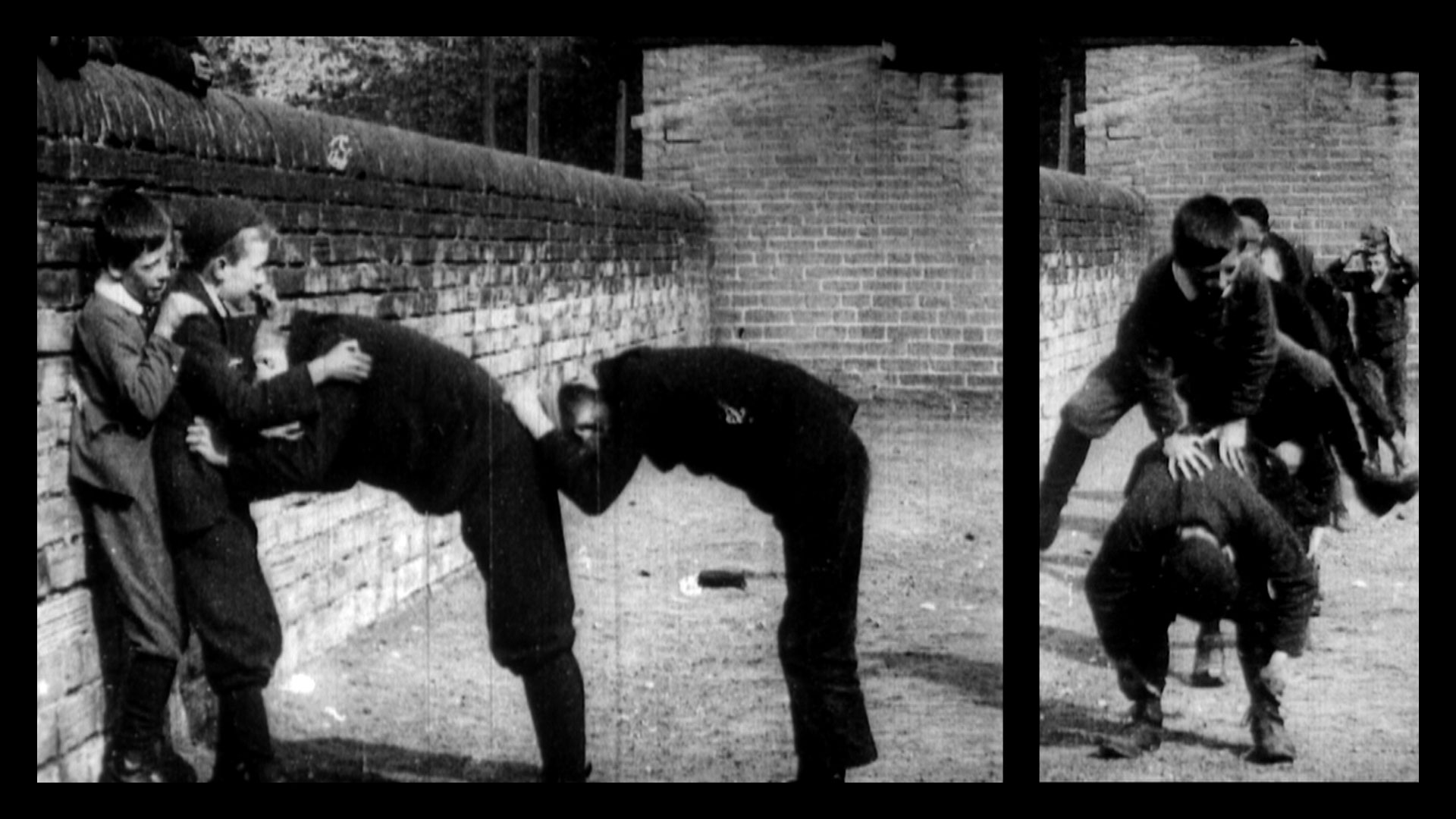

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Leap Frog

2012

Still from All This Can Happen

Courtesy of BFI National Archive

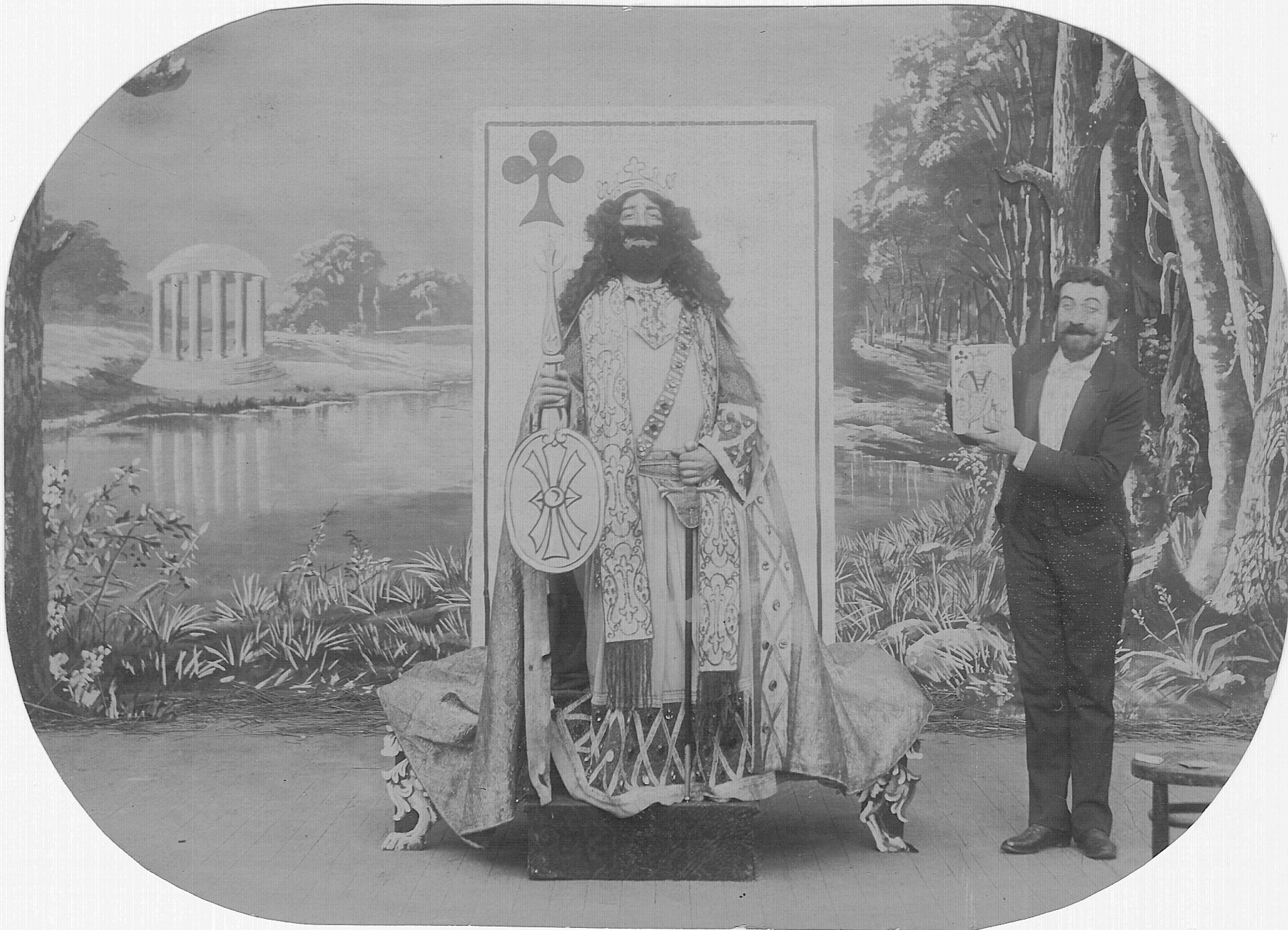

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Cheshire Territorials

2012

Still from All This Can Happen

Courtesy of BFI National Archive

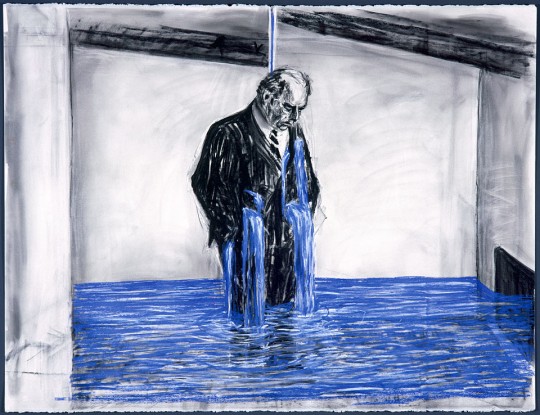

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Otto the Giant

2012

Still from All This Can Happen

Courtesy of British Pathé

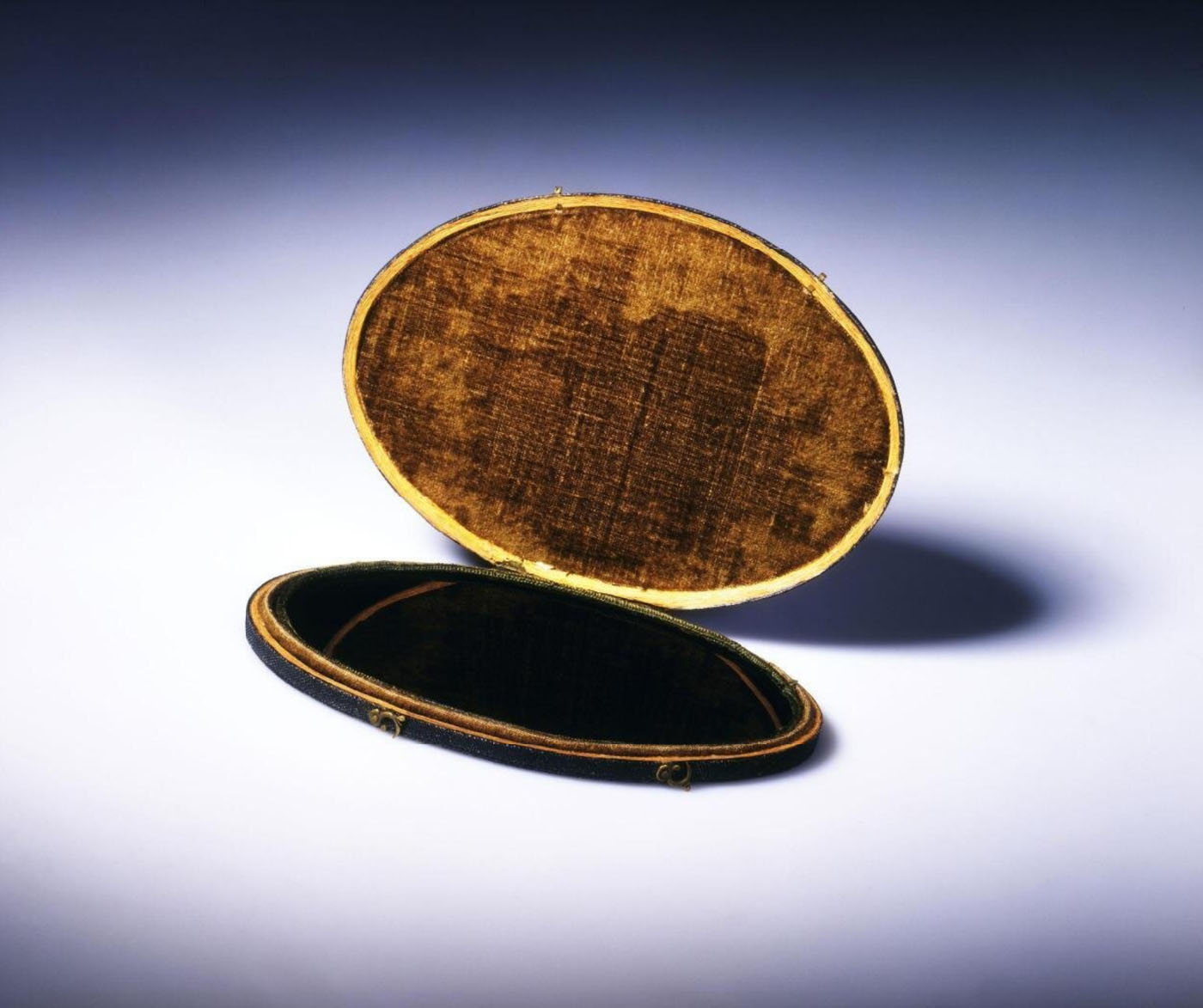

All This Can Happen, a 50-minute film by David Hinton and choreographer Siobhan Davies, opens with images of men who cannot walk. One lies immobile in a hospital bed, his head trembling, eyes vacant with torment. Another, also institutionalised, tries to walk but fails. He falls, scrambles and falls again, his whole body stiff with malfunction.

All this did happen. Every frame of this remarkable film comes from old, mostly black and white archive footage, complete with scratches and fingerprints. It is neither documentary nor constructed reality, but rather a wholly unexpected film adaptation of a short story by Swiss writer Robert Walser (1878-1956), about a man going for a walk.

The story, to which those opening images serve as a prologue, recounts the sights, sounds, encounters and musings of a day’s meandering: children playing in a school, a visit to the tax office, a display of women’s hats, a stroll through a forest, an argument with a tailor. Lovingly voiced by John Heffernan, the narration treats each moment, each thought and perception, with equal consideration, whether it is a gripe about automobiles, a memory of unbearable anguish, the sound of sublime music, or a chat with a dog. “The highest and the lowest, the most serious and the most hilarious things,” he explains, “are to the walker equally beloved, beautiful and valuable…

… the narration establishes a supple continuity, yet though the imagery follows the story devotedly, it has no continuity. It leaps between locations, splices scenes, switches subjects, and roams freely between poetic and literal modes, between the fantastic, the scientific, the surreal and the mundane. It seems able to let the whole world in, and still stay true to a singular storyline.

The imagery is discontinuous in other senses too. The screen is often split into multiple frames so that we notice how highly composed the film is. The frames themselves often freeze fleetingly, arresting the flow of time. Such stops literally give us pause; they let us take a moment. In fact, the whole film could be seen as the encounter between continuity – the story, the voice, time itself – and composition, or indeed choreography: the framing of action, the placement of sound, the arrangement of subjects and space.

But the reason to watch this film is not because it is artful and thoughtful, though it is that. It is because it restores us to our senses, because it touches – gently – both body and soul. To walk, it suggests, is to be in the world. A world that is physical, full of texture and sound and sensation; that is abstract, a matrix of space and time; that is imaginary, teeming with fantasies and terrors, desires, hopes and regrets; that is social, marked by encounters, engagements, negotiations; a world that is human. As a walk of life, All This Can Happen is, quite naturally, also shadowed by death, by not-walking, by not moving in space and time. “Where would I be,” asks the walker, “if I was not here? Here, I have everything. And elsewhere, I would have nothing.” All this it finds equally beloved, beautiful and valuable.

Sanjoy Roy. Excerpt of “Review of All This Can Happen, by Siobhan Davies and David Hinton” on the Aesthetica Magazine Blog website 5 November 2013 [Online] Cited 17/10/2022

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Miniature Writer

2012

Still from All This Can Happen

Courtesy of British Pathé

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Hints and Hobbies

2012

Still from All This Can Happen

Courtesy of AP Archive British Movietone

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Ears and Birth of a Flower

2012

Still from All This Can Happen

Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London and AP Archive British Movietone

Siobhan Davies and David Hinton

Banff Scotland and I Saw This

2012

Still from All This Can Happen

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division and Yorkshire Film Archive

You must be logged in to post a comment.