Exhibition dates: 4th May – 28th May 2011

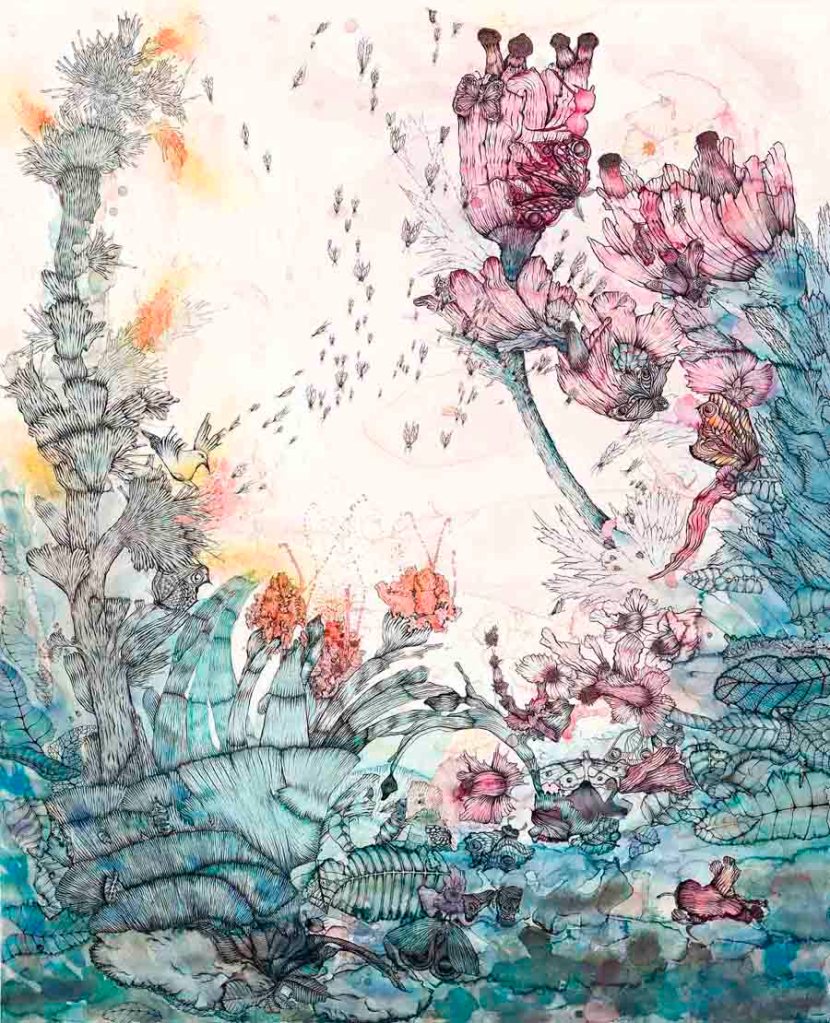

Monika Tichacek (Australian, b. 1975 Switzerland)

To all my relations

2011

Diptych

Gouache, pencil and watercolour on paper

244 x 300cm overall

This is a stupendous exhibition by Monika Tichacek, at Karen Woodbury Gallery. One of the highlights of the year, this is a definite must see!

The work is glorious in it’s detail, a sensual and visual delight (make sure you click on the photographs to see the close up of the work!). The riotous, bacchanalian density of the work is balanced by a lyrical intimacy, the work exploring the life cycle and our relationship to the world in gouache, pencil & watercolour. Tichacek’s vibrant pink birds, small bugs, flowers and leaves have absolutely delicious colours. The layered and overlaid compositions show complete control by the artist: mottled, blotted, bark-like wings of butterflies meld into trees in a delicate metamorphosis; insects are blurred becoming one with the structure of flowers in a controlled effusion of life. The title of the exhibition, To all my relations,

“has inspired an understanding that all animist cultures’ peoples have who live in close relationship to the earth. We are all related, we all exist in an interdependent system. The ecosystem is such an unbelievably complex, harmonious system. Every drop of rain, every insect, every micro-organism has its place for the perfect functioning and health of nature… The title is an acknowledgement and honouring of all that is live-giving, every little element that makes up the big picture of life on earth.”1

It was very difficult to pull myself away from the beauty and intimate polyphony of voices contained within the work. I loved it!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ O’Sullivan, Jane. “Artist Interview: Monika Tichacek,” on Australian Art Collector website, 19th May 2011 [Online] Cited 21/05/2010 no longer available online

Many thankx to Karen Woodbury Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs and Art Guide Australia for allowing me to publish the text in the posting. The text by Dylan Rainforth was commissioned by Art Guide Australia and appears in the May/June 11 issue of Art Guide Australia magazine. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Monika Tichacek (Australian, b. 1975 Switzerland)

To all my relations (detail)

2011

Diptych

Gouache, pencil and watercolour on paper

244 x 300cm overall

Monika Tichacek (Australian, b. 1975 Switzerland)

To all my relations (detail)

2011

Diptych

Gouache, pencil and watercolour on paper

244 x 300cm overall

Monika Tichacek (Australian, b. 1975 Switzerland)

To all my relations (detail)

2011

Diptych

Gouache, pencil and watercolour on paper

244 x 300cm overall

The Cycle of Nature – Monika Tichacek’s To All My Relations

Dylan Rainforth

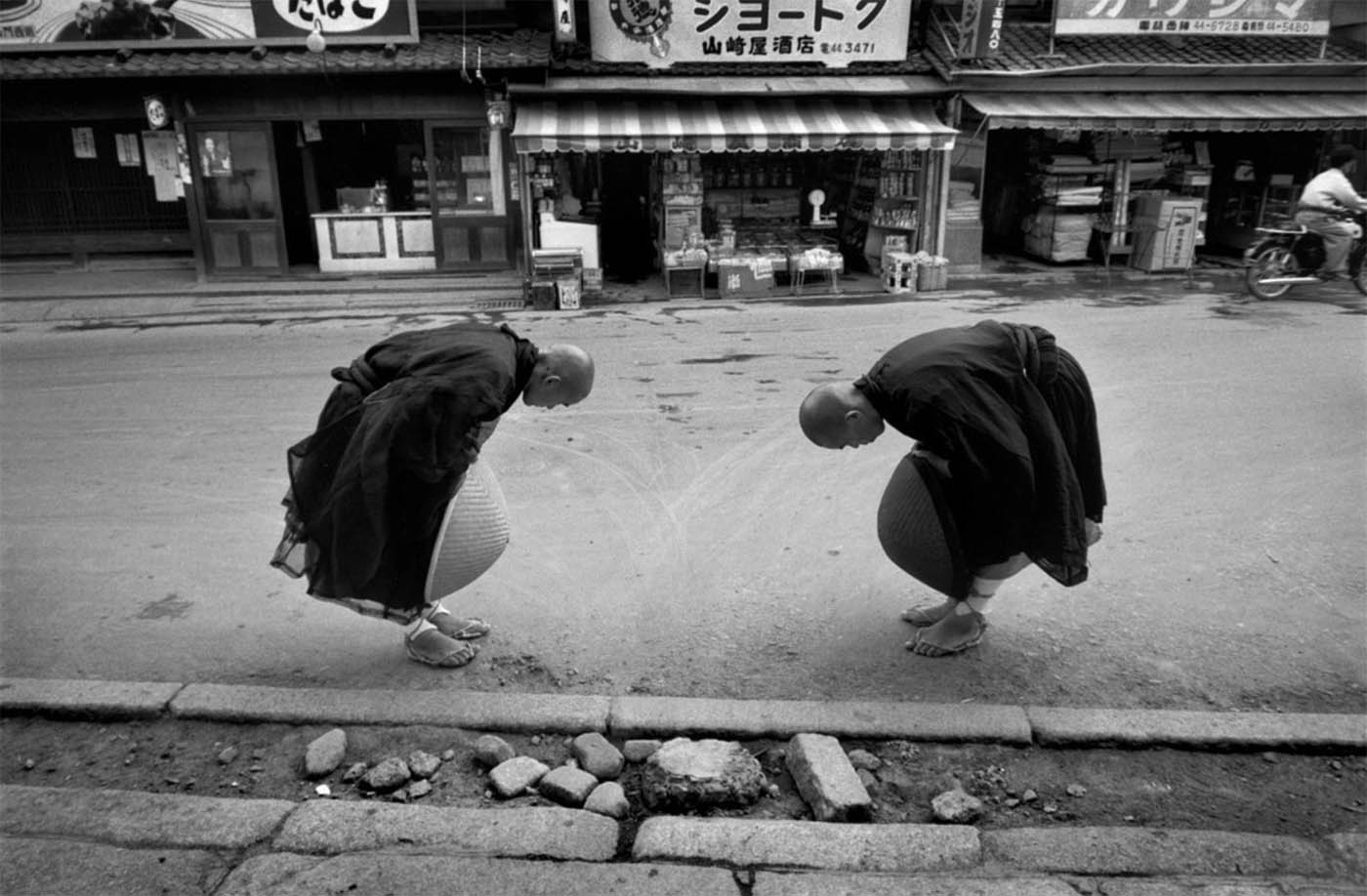

Anyone used to the immaculately controlled, exactingly lit photographic and video mise en scène that Swiss-born artist Monika Tichacek presented in such series as The Shadowers, for which she won the prestigious Anne Landa Award for Video and New Media Arts in 2007, may be surprised by the direction her work has taken in her latest exhibition. To All My Relations consists entirely of works on paper – watercolour and ink drawings that evince a tension between abstract, gestural shapes and bleeds of colour, recalling (just for convenience’s sake) Kandinsky, and intricately rendered natural forms that owe more to the scientific, zoological and botanical narratives of the Endeavour voyages of Captain Cook, Joseph Banks and the artist Sydney Parkinson.

The work has come out of an intensive period over the last few years in which Tichacek spent considerable time in the jungles of South America and the deserts of the United States, as well as time spent in the New South Wales bush and studying nature books. “I’m getting more and more interested in the cellular, microscopic imagery that you get when you enlarge something and peer deeper into the structure of how material elements are composed, and that really coincides with my interest in Eastern philosophies of Buddhism and many other things too. I guess I’m looking as deeply into the nature of something as is possible but I’m trying not to do it so much with my mind – but of course that’s very challenging,” she says, laughing lightly.

“The exploration of feeling is quite important to me – it’s quite a departure from what I used to do, which were certainly works that came from a very inner landscape but then the execution would be very conceptual, obviously – it had to be and this new work is much more intimate.”

That challenge to the rational, objective Western subject is informed by Tichacek’s exposure to indigenous traditions in South America and other places.

“In 2006 I had a research grant and I went to the Amazon because I wanted to look more deeply into animist cultures, meaning cultures that really see the land as living and as alive with energy and with spirit or ‘beingness’. So I went to the Amazon and spent quite a long time there and also in the mountains in Peru and saw a little bit of Central America and also North America in the desert. I spent time there and really learnt a lot about their indigenous ways and got to participate in a lot of things and experience a lot of things. In the Amazon shamanic tradition there is a process – they call it dieting – you spend a few months more or less alone, existing on very limited foods. You get very little, limited food and very little contact and they give you different traditional plants that, through the communion they do, they are ‘told’ to give you. And you are encouraged to connect with this plant for its healing properties to come through. So that was quite an amazing time to get quite still…”

The exhibition title comes from a Native American ceremony. According to Tichacek, “It’s always said when entering the sweat lodge and it’s an acknowledgement of being related to everything in nature, every being, the understanding that without all these other relations one wouldn’t exist. In those cultures it’s much more understood – we’ve lost that understanding because we can just buy things in the supermarket and eat them but if we lived that way we would probably remember a lot more that we are closely related to everything around us.”

From this perspective we can see that this new work is not a complete departure from Tichacek’s earlier work after all, yet its intentions are radically different. Both the natural world and shamanistic knowledge played their part in The Shadowers. Professor Anne Marsh has described Tichacek’s video, played out in a violent scene occurring between three women (one of whom Marsh characterises as a witch doctor or shaman) in a forest environment, as “stretch[ing] the boundaries between body art, ritual and sado-masochism by assaulting the senses and transgressing the social realm. In psychoanalytic terms it tears at the screen of the real and immerses the viewer into the abject world of instinctual response where language has no authority.” [i]

Pain, sado-masochism, ritual and endurance certainly have their place in shamanistic traditions – one need only think of any number of initiation rites – but now Tichacek is looking for a less conflicted relationship with nature. “The work has always been very personal and I guess in The Shadowers that nature relationship was starting to come in but it was very tense and very violent and very confused. The continuation of that theme is still there – the exploration of how to understand the experience of the self and what we are doing here and how we come to exist. That’s definitely been there before but this new work is more in the realm of psychology and the previous works are more in the realm of the female body.”

To All My Relations will present several drawings, with one in particular being conceived on a massive scale that Tichacek intends to convey the sense of awe we experience when surrounded by nature. The artist will also stage a performance – something her interdisciplinary practice has always embraced – at the opening. Although she had not completely determined the details when I spoke to her the performance was inspired by a drawing she made a few years ago and will symbolically connect the artist’s body to the roots of a tree.

“I always feel like [performance serves] to bring my body into it. Although I feel like my body’s very much in these drawings there’s something about performance that’s really physically present.”

Dylan Rainforth.

Monika Tichacek (Australian, b. 1975 Switzerland)

To all my relations (detail)

2011

Diptych

Gouache, pencil and watercolour on paper

244 x 300cm overall

Monika Tichacek (Australian, b. 1975 Switzerland)

To all my relations (detail)

2011

Diptych

Gouache, pencil and watercolour on paper

244 x 300cm overall

Monika Tichacek (Australian, b. 1975 Switzerland)

Birth of generosity

2011

Diptych

Pencil and watercolour on paper

70 x 114cm overall

Monika Tichacek (Australian, b. 1975 Switzerland)

Transmission

2011

Pencil and watercolour on paper

150 x 125cm

Karen Woodbury Gallery

This gallery has now closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.