Exhibition dates: 10th October, 2025 – 22nd February, 2026

Curators: Laurie Hurwitz and Shoair Mavlian in collaboration with Boris and Vita Mikhailov

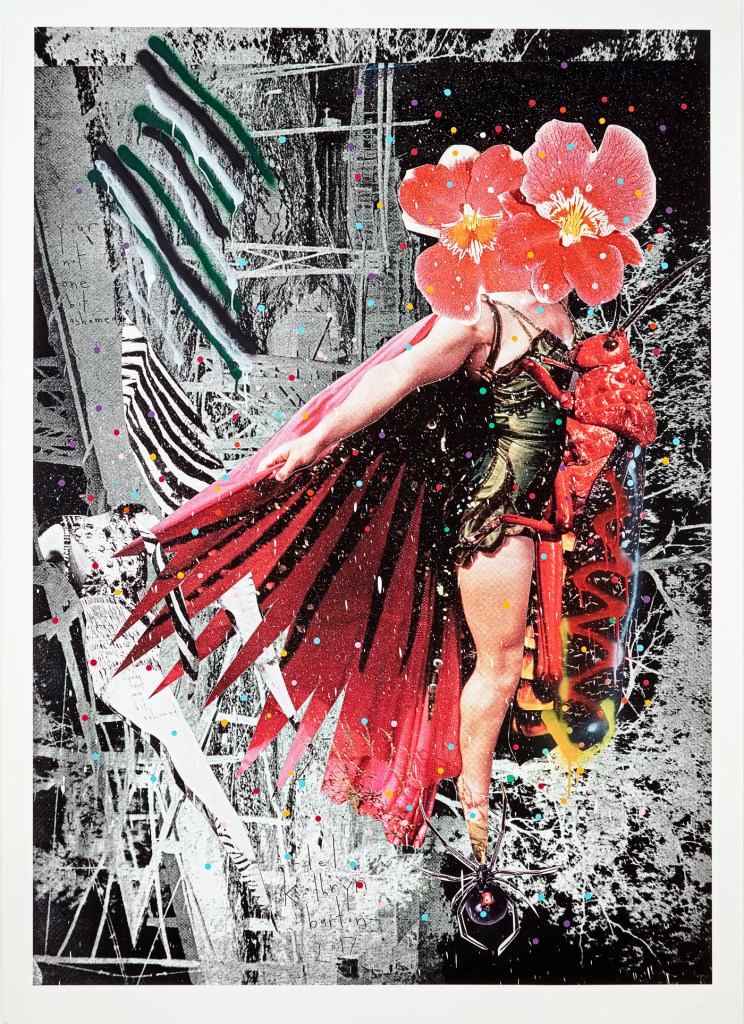

Installation view of the exhibition Boris Mikhailov: Ukrainian Diary at The Photographers’ Gallery, London showing at left, photographs from his series Luriki (1971-1985, below) and Sots Art (c. 1975-1986, below); and at right, a photograph from the series National Hero (1991, below)

“The world is made up of many worlds. Some are connected and some are not.”

From the film Perfect Days, 2023 directed by Wim Wenders

I love this man’s work. I feel very connected to his worlds. His constructed discontinuities. His ruptures, compressions, ambiguities. His social codifications of rich, poor, haves and have nots, and, as someone said, his portrayal of “the overlooked, the uncomfortable, and the unabashedly human.”

“Mikhailov’s visual pairings deliver unambiguous messages, almost violent in their straightforwardness. Multiple juxtapositions of unconsciously drunk men prostrating under passers-by feet to that of stray dogs, dead or alive, explicitly comment on human’s life disintegration to the state of an animal, its reduction to bare bones – and yes, an animal carcass, a metaphoric sign of abject poverty, is also present in this visual narrative in a scene with two men dragging a piece of spinal vertebrae of a large creature, a cow or, perhaps, a horse. Rotten banana peels sit across the page from infected flaccid limbs and genitalia. A posture of a naked woman reclining on a sullied mattress echoes that of a rubber sex doll staring from the next page. A close-up of a bruised woman’s breast with a crude stitches over a wound parallels gaping cracks of a damaged mail box. Thus the physical body of a homeless person starts speaking about the city as an organism, equally abused and dismembered. Wounds inflected upon flesh are surface manifestations of wounds inflected upon the city and the society at large.”1

“By subverting idealised Soviet imagery, he proposed a raw, ironic, and unremarkable version of reality, always seeking to capture the spirit of his times through the everyday. Or, better yet, to condense that spirit for others, not through words but through a visual semantics of his own making.”2

Experimental, conceptual, staged, performative, his photographs appeal to my subversive nature, prodding as they do at the status quo. His “rebellious visual language” takes us on a journey – his journey, Ukraine’s journey – “a journey through time, loss, and transformation.”

I wrote of his work in an earlier posting on this exhibition when it was at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP), Paris:

“Mikhailov’s photographs are emotionally powerful, politically astute and uncannily effective conversations with the world… about subjects that should matter to all of us: war, destitution, poverty, oppression, and the power of an authoritarian state to control the thoughts and actions of human beings under its control. They are about the freedom of individual people to live their lives as they choose; and they are about the freedom of a group of people which form a country to not be subjugated under the rule of another country to which they are historically linked.

His photographs are about choice and difference, they are about life.

They perform a task, that is, they bring into consciousness … the ground on which we stand together, against oppression, for freedom. Of course, no country is without its problems, its historical traumas, prejudices and corruption but the alternative is being ruled over without a choice, which is totally unacceptable.

Against the “failed promises of both communism and capitalism” and the “economic history that is written on the flesh” of the poor, Boris Mikhaïlov’s Ukrainian diary documents day after day the dis-ease and fragility, but also resilience, of his subjects and the world in which they live. He uses his art as a visual tool for cultural resistance. And the thing about his images is: you remember them. They are unlike so much bland, conceptual contemporary photography because these are powerful, emotional images. In their being, in their presence, they resonate within you.”

In this earlier posting you will find a longer text that I wrote, descriptions of the each of the artist’s series and more images. I hope you can view the posting.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Extract from Olena Chervonik, “Urban Opera of Boris Mikhailov,” on the MOKSOP website, 9th April 2020 [Online] Cited 27/01/2026

2/ Kateryna Filyuk. “Recalcitrant Diarist of the Everyday,” on The Photographers’ Gallery website Nd [Online] Cited 05/02/2026

Many thankx to The Photographers’ Gallery, London for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I chose to focus on ordinary, everyday scenes and the search for formal solutions to translate this mundaneness into photography.”

Boris Mikhailov, “Everyone has became more circumspect…,” in Tea Coffee Cappuccino. Köln: König, 2011, p. 230

“Central themes – heroism, failure, power, the body, identity, absurdity, ideology – recur throughout, not as definitive conclusions but as open-ended provocations that invite sustained contemplation. In this way, the exhibition operates as both a temporal sequence and a constellation of moments – fragmented yet interconnected – that collectively evoke the complexity, contradictions, and richness of Mikhailov’s visionary practice.”

Laurie Hurwitz curator

“The explicit, dramatic and total power of the absolute monarch had given place to what Michel Foucault has called a diffuse and pervasive ‘microphysics of power’, operating unremarked in the smallest duties and gestures of everyday life. The seat of this capillary power was a new ‘technology’: that constellation of institutions – including the hospital, the asylum, the school, the prison, the police force – whose disciplinary methods and techniques of regulated examination produced, trained and positioned a hierarchy of docile social subjects in the form required by the capitalist division of labour for the orderly conduct of social and economic life.”

John Tagg. The Burden of Representation. Essays on Photographies and Histories. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993

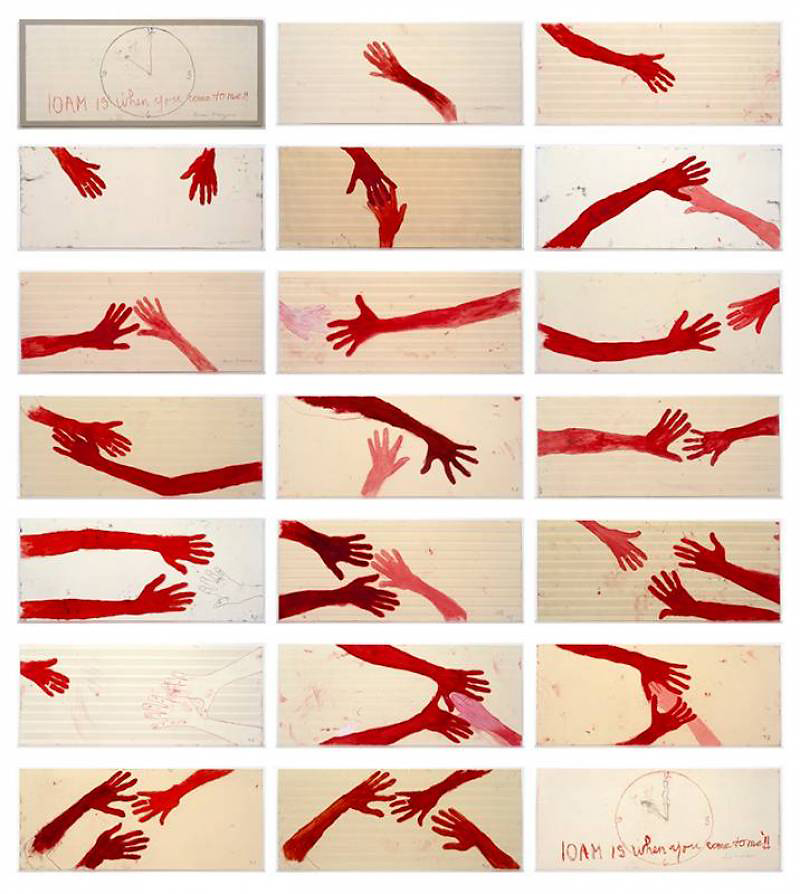

From the beginning, we conceived two video works as conceptual bookends. At the entrance, Yesterday’s Sandwich – a seminal project from the late 1960s – presents a hallucinatory sequence of double exposures set to music by Pink Floyd. These psychedelic, surreal images, rejecting Soviet visual orthodoxy, open up a new, rebellious visual language. At the exit, Temptation of Death (2019) offers a quieter, meditative counterpoint. Combining images from a crematorium in Ukraine with intimate portraits and cityscapes, it evokes the myth of Charon, ferryman of the dead, and a journey through time, loss, and transformation. Together, these two works, created nearly fifty years apart, frame the exhibition with a meditation on mortality, reinvention, and the fragile persistence of life.

Lucile Brizard. “”Where are we now?”: An Exclusive Interview with Photographer Boris Mikhailov on Ukraine’s Past and Present,” on the United 24 Media website, October 29, 2015 [Online] Cited 27/01/2026

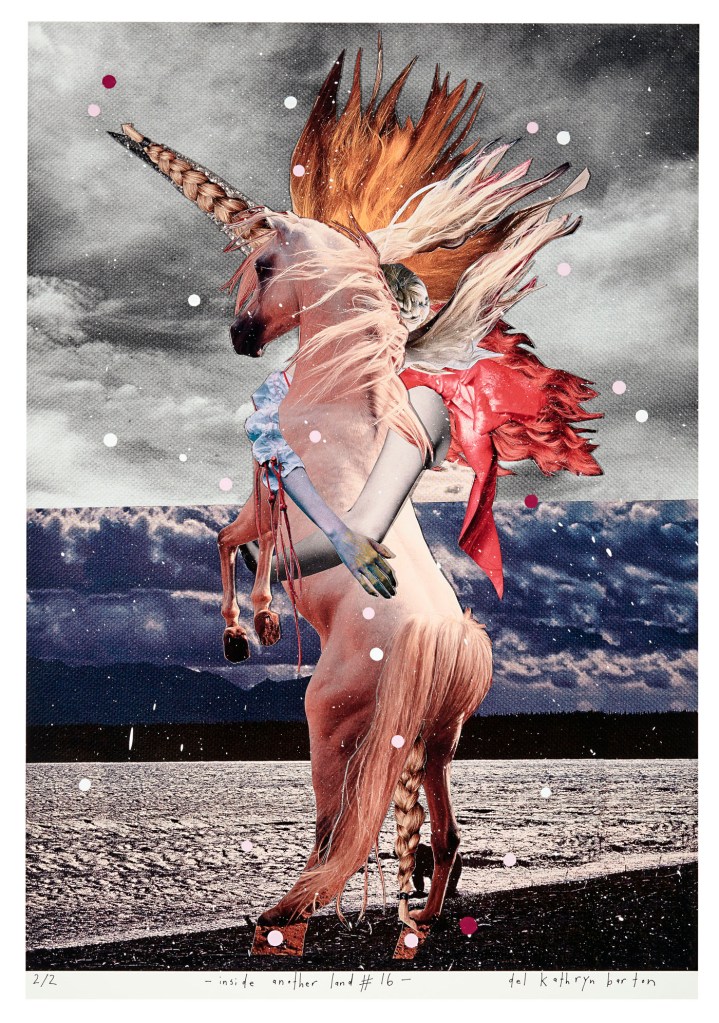

Luriki, 1971-1985

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Luriki (Coloured Soviet Portrait)

1971-1985

Hand-coloured gelatin silver print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Luriki (Coloured Soviet Portrait)

1971-1985

Hand-coloured gelatin silver print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

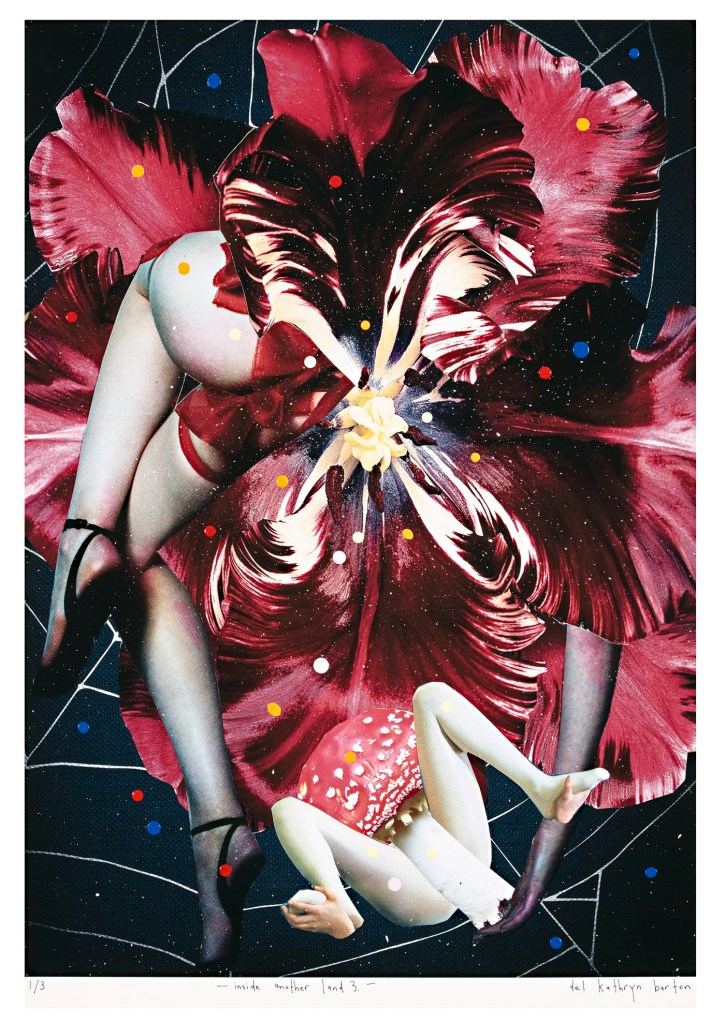

Sots Art, 1975-1986

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Sots Art

1982-1983

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

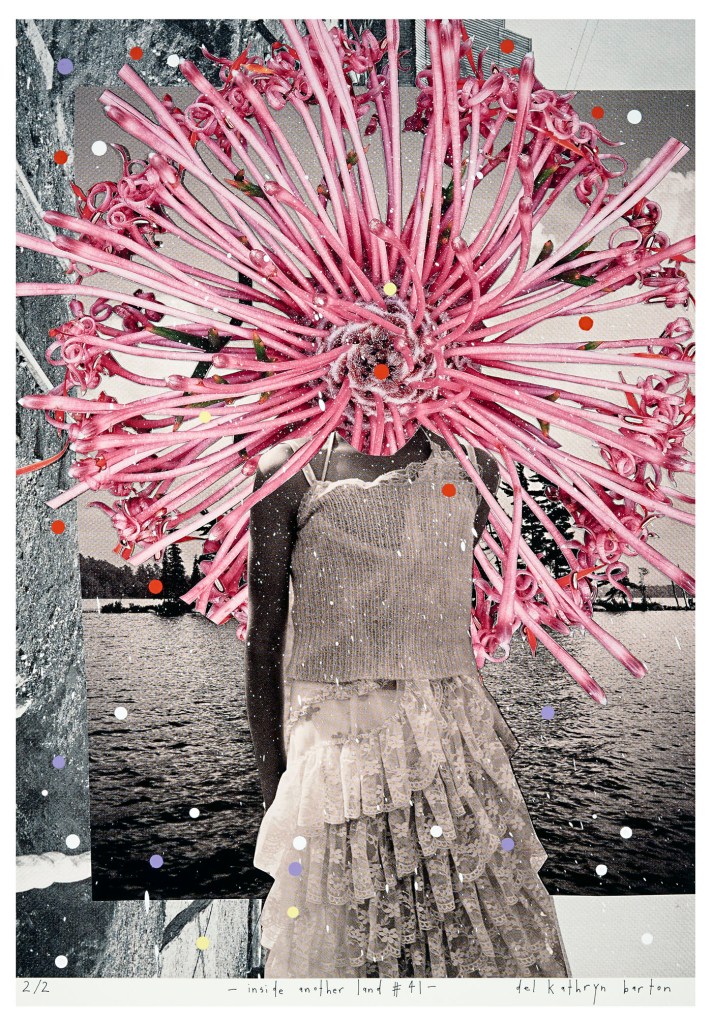

National Hero, 1992

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series National Hero

1991

Chromogenic print

120 x 81cm

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Installation view of the exhibition Boris Mikhailov: Ukrainian Diary at The Photographers’ Gallery, London showing at left, photographs from his series Salt Lake (1986, below); at at right in the background, photographs from his series I am not I (1992, below)

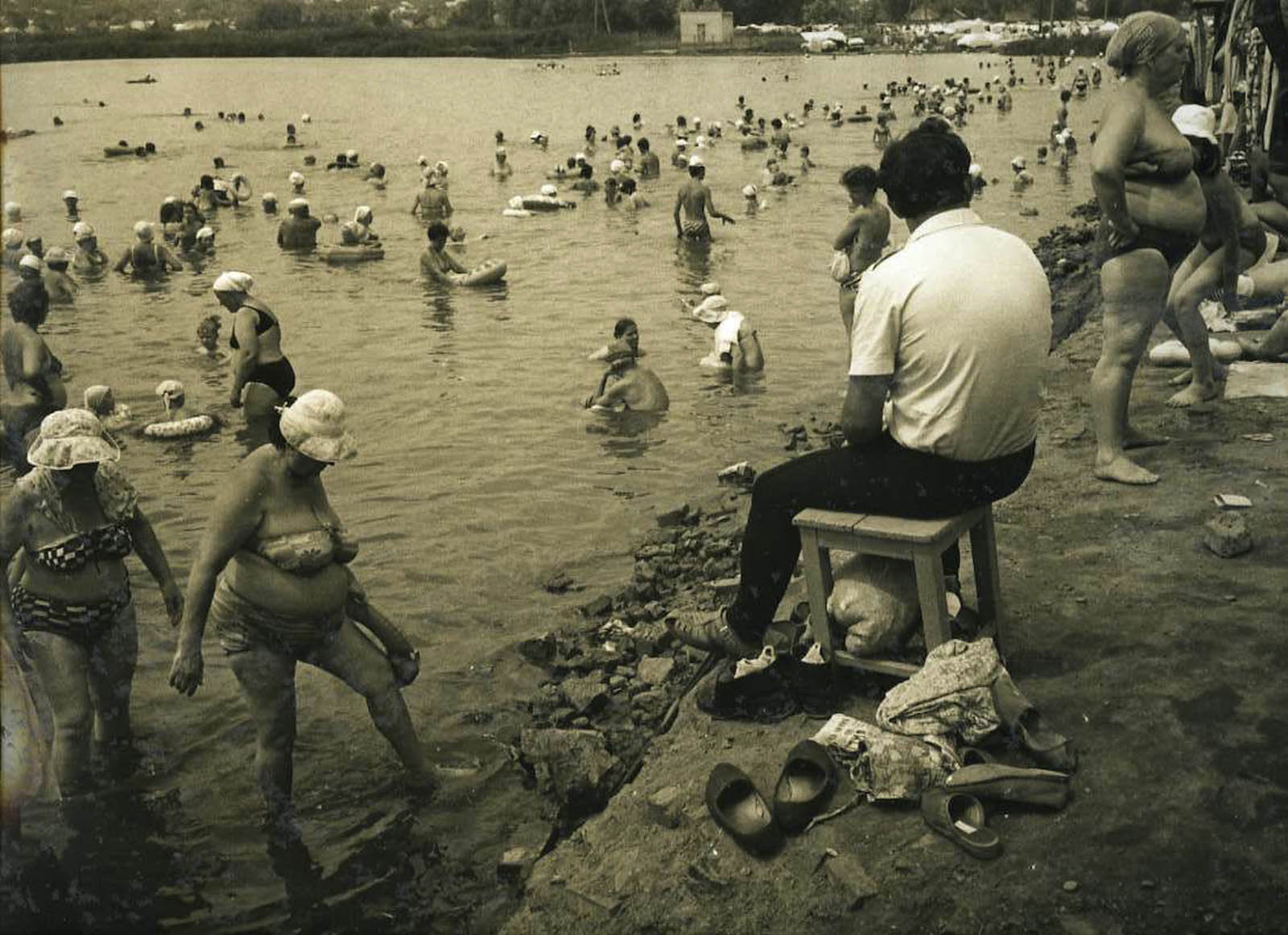

Salt Lake, 1986

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series Salt Lake

1986

Chromogenic print toned sepia

75.5 x 104.5cm

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

I Am Not I, 1992

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series I am not I

1992

Sepia silver print

30 x 20cm

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

A major retrospective of work by influential Ukrainian artist Boris Mikhailov (b. 1938, Kharkiv, Ukraine).

Ukrainian Diary is the first major UK retrospective of work by Boris Mikhailov, one of the most influential contemporary artists from Eastern Europe. Mikhailov has explored social and political subjects for more than fifty years through his experimental photographic work.

Described as an outsider, a trickster and ‘a kind of proto-punk’, Mikhailov combines humour, mischief and tragedy in his pioneering practice, ranging from documentary photography and conceptual work, to painting and performance. Since the 1960s, he has been creating a powerful record of the tumultuous changes in Ukraine that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Ukrainian Diary brings together work from over twenty of his most important series, up to his more recent projects. Viewed today, against the backdrop of current events and ongoing war in Ukraine, Mikhailov’s work is all the more poignant and enlightening.

Text from The Photographers’ Gallery website

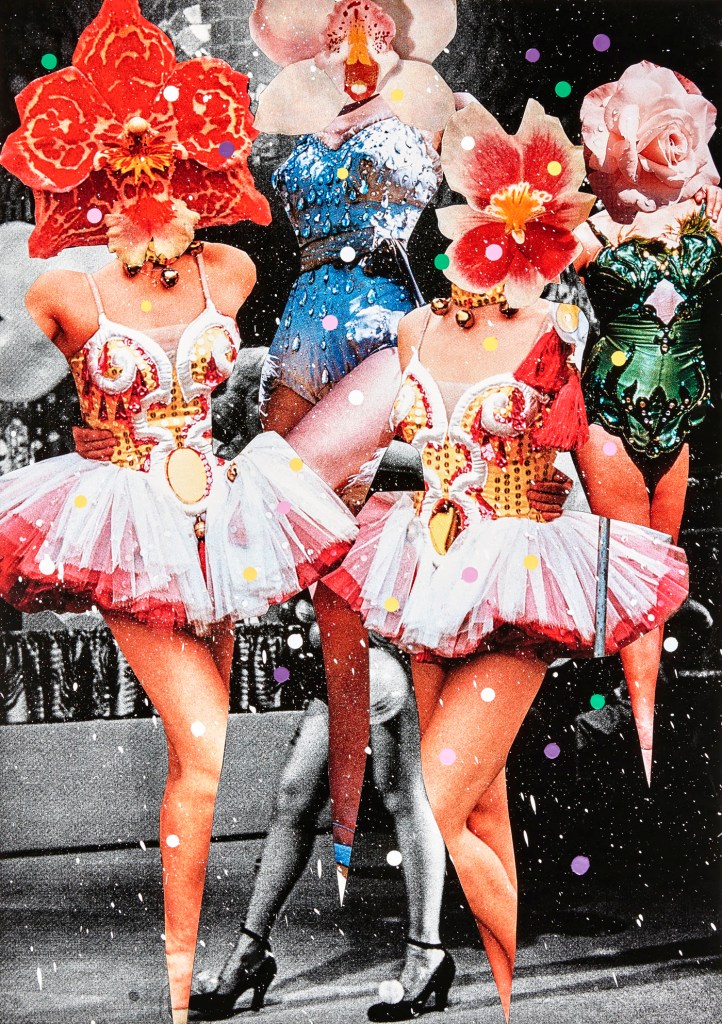

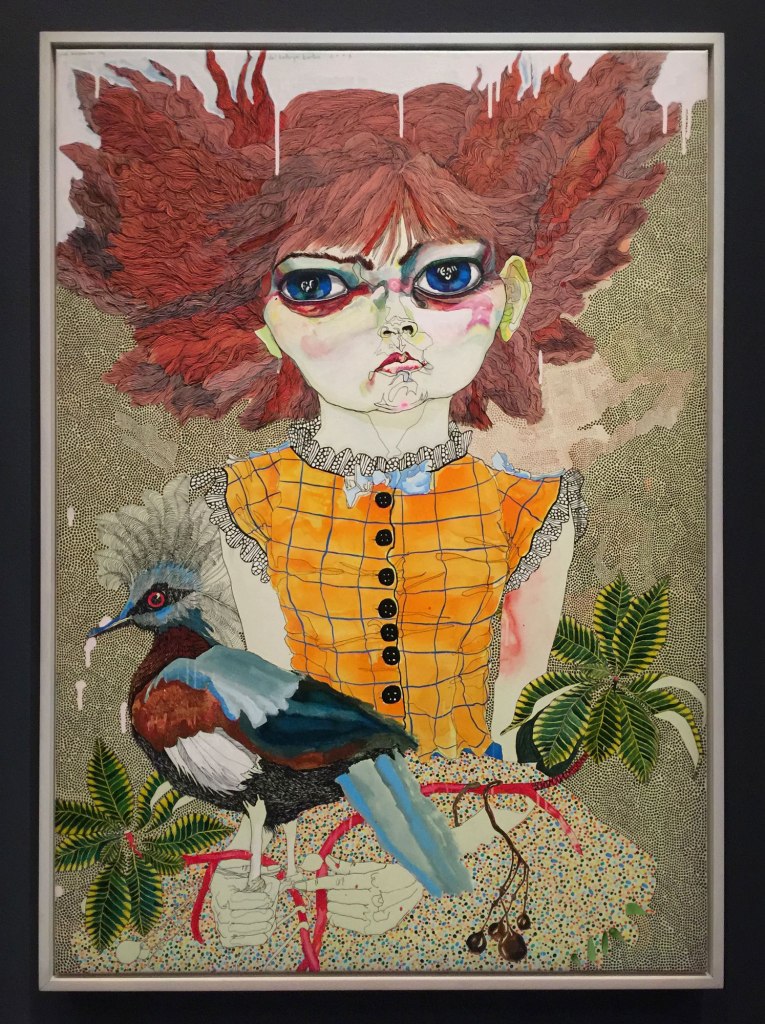

Red, 1965-1978

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series Red

1968-1975

Digital chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

“The word ‘red’ in Russian contains the root of the word for beauty. It also means the Revolution and evokes blood and the red flag. Everyone associates red with Communism. Maybe that’s enough. But few people know that red suffused all our lives, at all levels.”

Boris Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series Red

1968-1975

Digital chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series Red

1968-1975

Digital chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Yesterday’s Sandwich, 1960s-1970s

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Yesterday’s Sandwich

1960s-1970s

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Yesterday’s Sandwich

1966-1968

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Yesterday’s Sandwich

1966-1968

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Yesterday’s Sandwich

1966-1968

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Yesterday’s Sandwich

1960s-1970s

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Yesterday’s Sandwich

1966-1968

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Ukrainian Diary is the first major UK retrospective of work by Boris Mikhailov (b. 1938, Kharkiv). One of the most influential contemporary artists from Eastern Europe, Mikhailov has explored social and political subjects for more than fifty years through his experimental photographic work.

Described as an outsider, a trickster and ‘a kind of proto-punk’, Mikhailov combines humour, mischief and tragedy in his pioneering work, ranging from documentary photography and conceptual work, to painting and performance. Since the 1960s, he has been creating a powerful record of life in the Ukraine and the tumultuous changes that accompanied the collapse of the Soviet Union.

From early underground works and images of everyday life in Kharkiv, to his self-depreciating self-portraits which mock traditional Soviet masculine stereotypes, Mikhailov creates an ambiguous, fragmented view of a world in constant flux. His photographs contradict the onesideness of Soviet ideology, especially during the time when photography was heavily controlled and censored in the Soviet Union.

Ukrainian Diary brings together work from over twenty of Mikhailov’s most important series, including Yesterday’s Sandwich, I am not I, Salt Lake, Red, Sots Art, Luriki, Case History and Theatre of War.

Self-taught and ‘somewhat careless’ (in his words), Yesterday’s Sandwich (1960s-1970s), one of his most important series, began as an accident when a handful of slides stuck together. He was fascinated by the result and continued to randomly layer slides, creating new combinations which ‘reflected the dualism and contradictions of Soviet Society’.

Mikhailov created ‘bad photography’ as a way to undermine official Soviet aesthetics, as introduced in the series Black Archive (1968-1979). Badly printed, damaged or poor-quality productions were an artistic device that Mikhailov described as ‘lousy photography for a lousy reality’.

The series Red (1965-1978) bridges documentary photography and conceptual art – over 70 images taken in the late 1960s and 1970s highlighting the colour red in everyday objects and scenes. His documenting of red reveals the extent to which communist ideology saturated daily life.

Together his uncompromising, subversive work is a powerful photographic narrative on Ukraine’s contemporary history.

The exhibition is organised in collaboration with the MEP – Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris.

About Boris Mikhailov

Born in Kharkiv, Ukraine in 1938, Boris Mikhailov is a self-taught photographer. Having trained as an engineer, he was first introduced to photography when he was given a camera to document the state-owned factory where he worked. With access to a camera, he took advantage of this opportunity to take nude photographs of his first wife – an act forbidden under Soviet norms – which he developed and printed in the factory’s laboratory. He was fired when the photographs were found by KGB agents. From then he pursued photography full time, using it as a subversive tool and operating as part of the underground art scene. His work first gained international exposure in the 1990s with the series Case History, a shockingly direct portrayal of the realities of post-Soviet life in the Ukraine.

Press release from The Photographers’ Gallery

Series of Four, early 1980s

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series Series of four

1982-1983

Silver gelatin print, unique copy

From a 20-part series

Each 18 x 23.80cm

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

At Dusk, 1993

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series At Dusk

1993

Chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series At Dusk

1993

Chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Recalcitrant Diarist of the Everyday

Curator and researcher, Kateryna Filyuk, explores the intimate diaristic qualities of Boris Mikhailov’s subversive body of work.

Even before seeing Ukrainian Diary at The Photographers’ Gallery, I found myself thinking about its title. The idea of a diary fits naturally with Mikhailov’s work: instead of creating a grand, official narrative inherent to Soviet photography, he developed an intimate and fragmented way of seeing. The term Ukrainian, however, is less straightforward. Some of his more recent bodies of work that directly address Ukrainian events: Parliament (2015-17); and Temptation of Death (2014-19), which adopts the Kyiv Crematorium as its binding motif, are not included in the exhibition.

Mikhailov began challenging Soviet photographic norms as early as the mid-1960s, working with a circle of like-minded friends. At the time, photographing “for no reason” could be equated with spying; showing Soviet life as anything less than ideal was seen as an attack on communist values; and photographing the naked body could result in prison. Mikhailov did all of this and more. He turned his camera toward mundane subjects, mixed genres freely and questioned photography’s claim to present an ultimate truth. By subverting idealised Soviet imagery, he proposed a raw, ironic, and unremarkable version of reality, always seeking to capture the spirit of his times through the everyday. Or, better yet, to condense that spirit for others, not through words but through a visual semantics of his own making.

Art historian Nadiia Bernard-Kovalchuk reflects on whether Ukrainian is an appropriate label for the Kharkiv School of Photography, of which Mikhailov is a founding figure. She writes that ”the school’s activities stretch between two heterogeneous historical realities: on the one hand, Brezhnev’s ‘stagnation’ and the perestroika fatal to the USSR, and on the other, the economically brutal birth of the Ukrainian state.” [2] This dramatic time span, during which Ukrainians experienced long-awaited yet destabilising transformation, offers a more fitting temporality for understanding Mikhailov’s work in Ukrainian Diary. Geographically, most of his projects take place in what was first Soviet Ukraine and later became independent Ukraine. Temporally, however, they exist within a landscape marked by ruptures, discontinuities, and perpetual new beginnings.

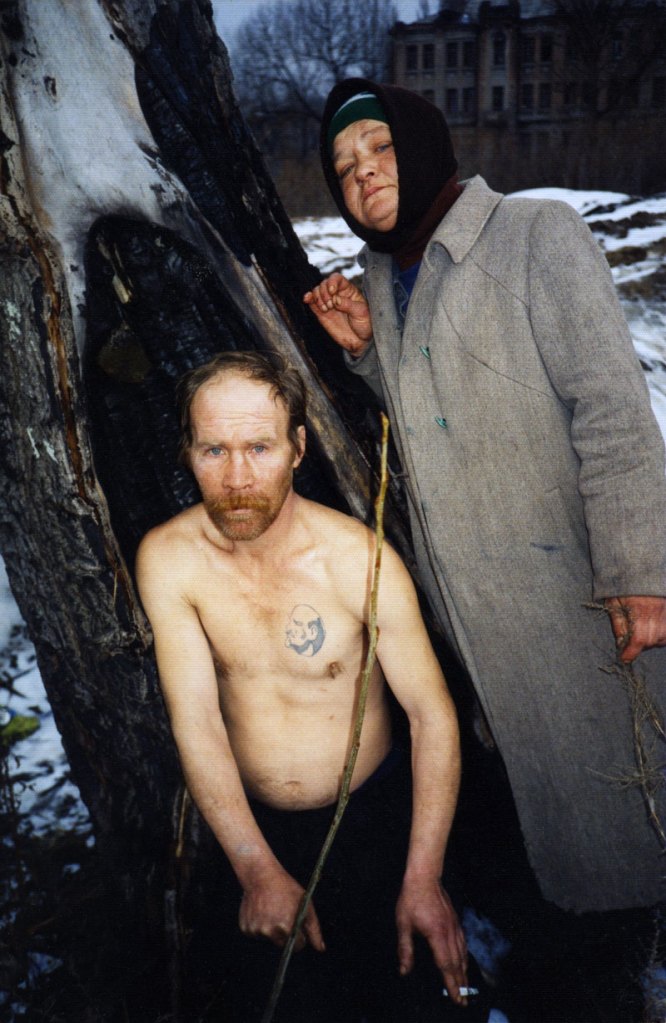

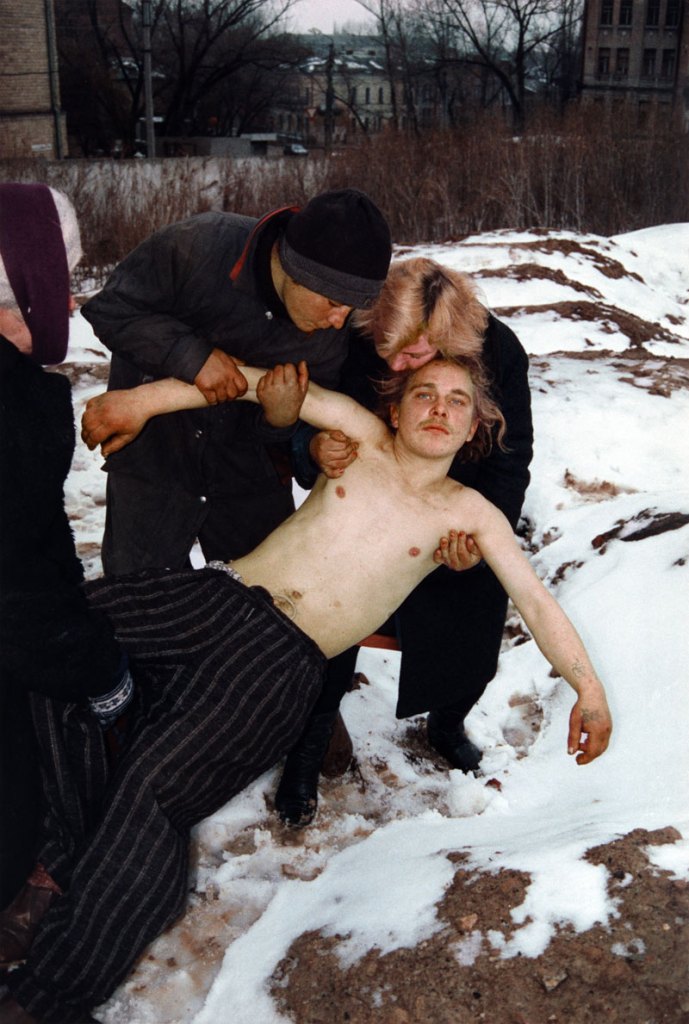

In the preface to one of his most audacious works, Case History (1997-98), Mikhailov reflects on the lack of a photographic record documenting complex historical shifts in Ukraine: ”I was aware that I was not allowed to let it happen once again that some periods of life would be erased.” [3] After returning to Kharkiv from a year in Berlin, he was struck by the stark divide between the newly rich and the newly poor, a process already in full swing. Yet his aim in photographing the homeless did not follow the classic documentary model, such as the USA Farm Security Administration’s work, which sought to highlight a social problem and prompt state intervention. Instead, by showing the everyday lives of those most affected by the collapse, Mikhailov “directly assaults the onlookers’ sensitivity” [4] and “transgresses the acceptable limits of representation,” [5] His goal was not to provoke pity or shock though.

Rather, Mikhailov asserts something more fundamental: the individual’s right to exist and express themselves beyond convention. Through his unwavering attention to ordinary lives, he bears witness to massive transformations unfolding beyond any single person’s control. Ukrainian Diary, then, is not simply a national label or a chronological record. It is a testament to how one artist has persistently documented a world defined by instability, reinvention, and the fragile, but enduring presence, of everyday life.

Kateryna Filyuk

Kateryna Filyuk is a curator and researcher, who holds PhD from the University of Palermo. In 2017-2021 she served as a chief curator at Izolyatsia., a Platform for cultural initiatives in Kyiv. Before joining Izolyatsia, she was co-curator of the Festival of Young Ukrainian Artists at Mystetskyi Arsenal, Kyiv (2017). The co-founder of the publishing house 89books in Palermo, she has participated in curatorial programmes at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo (Turin, 2017), De Appel (Amsterdam, 2015-16), the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (Seoul, 2014) and the Gwangju Biennale (2012). In 2023 Filyuk was a visiting PhD student at the Central European University (Vienna) and in 2024 a visiting researcher at FOTOHOF Archiv (Salzburg) and the Predoctoral Fellow at the Bibliotheca Hertziana (Rome). Currently she develops a two-year scholarly initiative – the Methodology Seminars for Art History in Ukraine in collaboration with the Bibliotheca Hertziana and the Max Weber Foundation’s Research Centre Ukraine.

Footnotes

1/ Boris Mikhailov, “Everyone has became more circumspect…,” in Tea Coffee Cappuccino (Köln: König, 2011), 230.

2/ Nadiia Bernard-Kovalchuk, The Kharkiv School of Photography: Game Against Apparatus. Kharkiv: Museum of Kharkiv School of Photography, 2020, 17.

3/ Boris Mikhailov, Case History (Zurich: Scalo, 1999), 7.

4/ “Symbolic Bodies, Real Pain: Post-Soviet History, Boris Mikhailov and the Impasse of Documentary Photography,” in The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture (London: Wallflower Press, 2007), 58.

5/ Olena Chervonik, “Urban Opera of Boris Mikhailov,” MOKSOP, accessed November 25, 2025

Text from The Photographers’ Gallery website

Installation view of the exhibition Boris Mikhailov: Ukrainian Diary at The Photographers’ Gallery, London showing photographs from his series Case History (1997-1998, below)

Case History, 1997-1998

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series Case History

1997-1998

Chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series Case History

1997-1998

Chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series Case History

1997-1998

Chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

Urban opera of Boris Mikhailov

Olena Chervonik

In the [Case History] book preface, Mikhailov explains that already in 1997 he vividly apprehended the rupture of Ukrainian society into new, burgeoning social strata, when the new rich and the new poor began to acquire features of class identities with their own psychology and behavioural modalities. The new rich were already hard to approach, protecting themselves with bodyguards and other social fences. The new poor, however, specifically the bomzhes (homeless people with no social support) could still allow an outsider in their midst – this was “a chance”, according to Mikhailov, that could only last for a short period of time. Most of the book’s protagonists had only recently lost their homes. Their rapidly deteriorating social position was still uncertain, malleable, and flickering with hope. Yet, the transformation was inevitable, which propelled the artist to act: “For me it was very important that I took their photos when they were still like “normal” people. I made a book about the people who got into trouble but didn’t manage to harden so far.” [2] …

Mikhailov’s visual pairings deliver unambiguous messages, almost violent in their straightforwardness. Multiple juxtapositions of unconsciously drunk men prostrating under passers-by feet to that of stray dogs, dead or alive, explicitly comment on human’s life disintegration to the state of an animal, its reduction to bare bones – and yes, an animal carcass, a metaphoric sign of abject poverty, is also present in this visual narrative in a scene with two men dragging a piece of spinal vertebrae of a large creature, a cow or, perhaps, a horse. Rotten banana peels sit across the page from infected flaccid limbs and genitalia. A posture of a naked woman reclining on a sullied mattress echoes that of a rubber sex doll staring from the next page. A close-up of a bruised woman’s breast with a crude stitches over a wound parallels gaping cracks of a damaged mail box. Thus the physical body of a homeless person starts speaking about the city as an organism, equally abused and dismembered. Wounds inflected upon flesh are surface manifestations of wounds inflected upon the city and the society at large. …

The majority of Mikhailov’s photographs provide no emotional crutches to lean on, no mechanism of ennobling or aestheticising infected abused flesh of the homeless. It is presented “as is”: frontal, looming large with all its detailed naturalistic vividness. If there is a visual code that Mikhailov activates in these images, it comes from a clinical rather than an art discourse, from surveilling patents for medical records. It is a discourse that John Tagg described as a nineteenth century record-keeping practice associated with certain disciplinary institutions such as an asylum or a prison that with the help of photography created a new social body of dependent subjects upon whom power could be exercised due to their newly-minted subaltern position.

Art, following Barthes’ dictum, domesticates and tames photography [21]. It generates the level of “studium”, accepted cultural knowledge that veils the trauma, renders it familiar, therefore trivial, therefore easily dismissed. Mikhailov makes his viewers constantly oscillate between images that give themselves for contemplation and images that confront with their clinical nature that can be scrutinised and observed but certainly not contemplated. Not one or the other type of image, but the switch between the two unsettles the viewing process. Mikhailov orchestrates poses and gestures of his subjects to create this visual roller-coster of plunging in and out of the aesthetic.

2/ Boris Mikhailov, Case History (Zurich: Scalo, 1985)

21/ Matthias Christen, “Symbolic Bodies, Real Pain: Post-Soviet History, Boris Mikhailov and the Impasse of Documentary Photography,” in The Image and the Witness. Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture (London: Wallflower Press, 2007), 52-66

Extract from Olena Chervonik, “Urban Opera of Boris Mikhailov,” on the MOKSOP website, 9th April 2020 [Online] Cited 27/01/2026. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Dance, 1978

Boris Mikhaïlov (Ukrainian, b. 1938)

From the series Dance

1978

Chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Courtesy Boris and Vita Mikhailov

The Theater of War, Second Act, Time Out, 2013

Boris Mikhaïlov (Russian, b. 1938)

From the series The Theater of War, Second Act, Time Out

2013

Chromogenic print

© Boris Mikhailov, VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Collection Akademie der Künste, Berlin

The Photographers’ Gallery

16-18 Ramillies Street

London

W1F 7LW

Opening hours:

Mon – Wed: 10.00 – 18.00

Thursday – Friday: 10.00 – 20.00

Saturday: 10.00 – 18.00

Sunday: 11.00 – 18.00

You must be logged in to post a comment.