Exhibition dates: 4th February – 13th May 2012

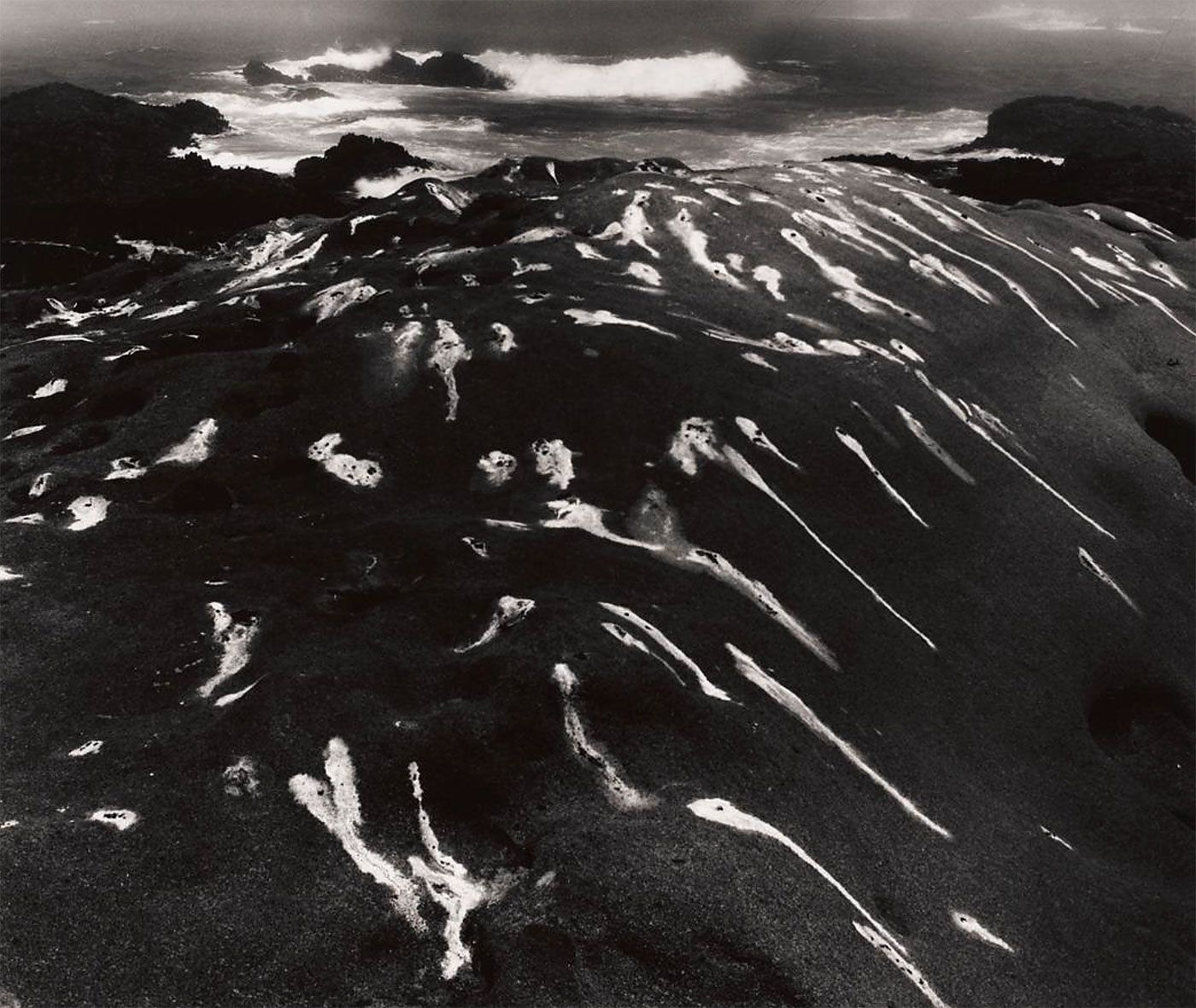

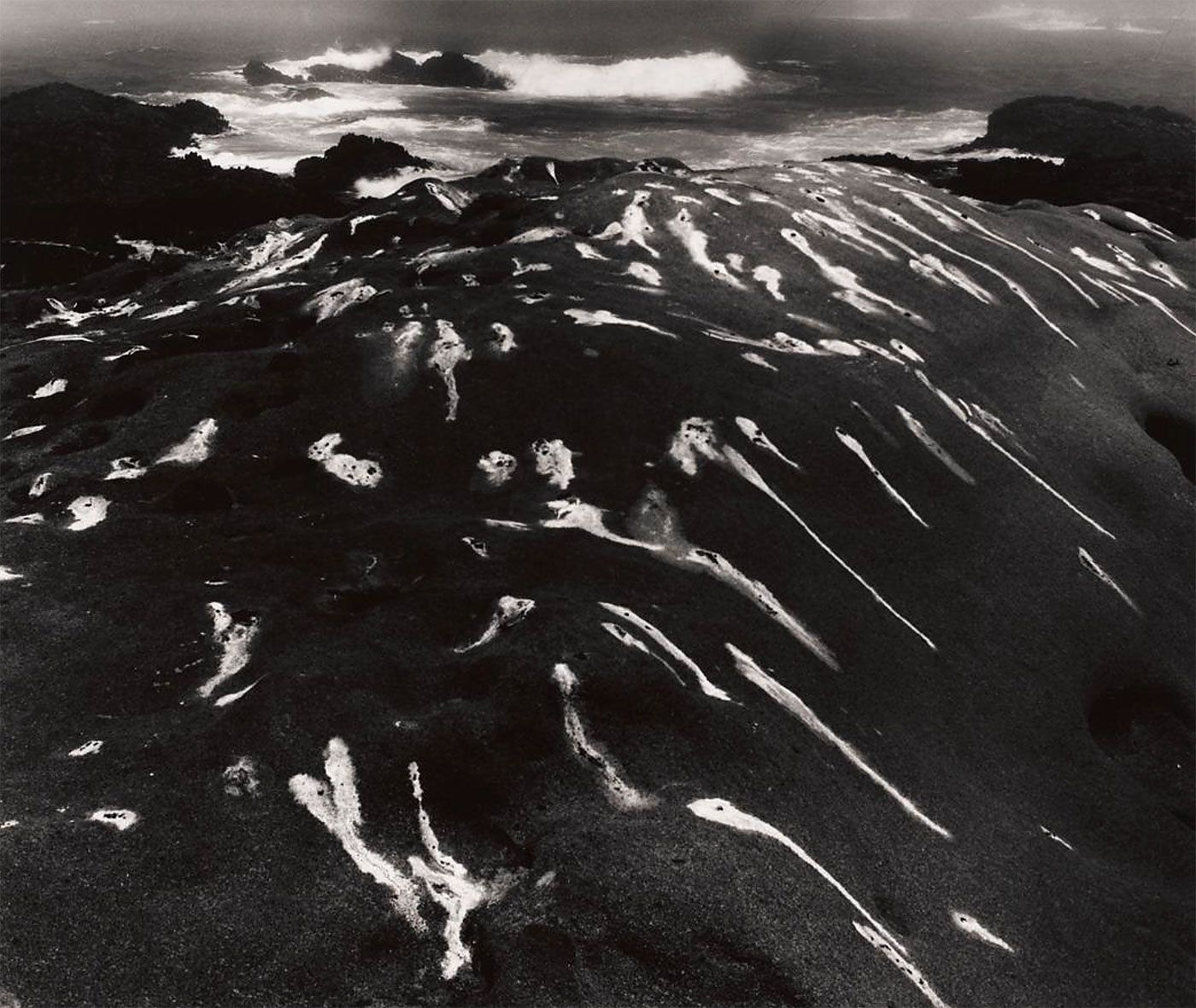

Minor White (American, 1908-1976)

Bird Lime and Surf, Point Lobos, CA

1951

Gelatin silver print

8 1/4 in. x 10 3/8 in. (20.96 x 26.35cm)

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Gift of Edith Vallarino

The conceptual idea of Modernist photography is “look at this,” look at how photography interprets the world: through light, lens, glass, film, paper, brain and eye. Early Modernist photography occurred in the first two decades of the twentieth century (through the vision of Alfred Steiglitz, Paul Strand, Edward Steichen et al) before it was even named “Modernism” and led to radically different forms of artistic expression that broke the pictorialist conventions of the era. Gritty realism was the order of the day, clean lines, repetition of form, strange viewpoints where the photographers observation of the subject is as important as the subject itself. Look at how I, and the camera, see the world: that is all there is, the indexical relation to the word of truth.

“Artists and photographers began looking at the photographs used in mass culture, to develop an aesthetic true to the intrinsic qualities of photographic materials: the accurate rendition of visible reality; framing that crops into a larger spatial and temporal context; viewpoints and perspectives generated by modern lenses and typically modern spatial organisations (for example, tall buildings); and sharp, black-and-white images. This objective, mechanised vision became art by foregrounding not its subject matter, but its formal structure as an image.”1

Steiglitz and Strand, “often abstracted reality by eliminating social or spatial context; by using viewpoints that flattened pictorial space, acknowledging the flatness of the picture plane; and by emphasising shape and tonal rendition in highlights and shadows as much as in the actual subject matter.”2 Such use of highlights and shadows can be seen in the most famous work by the photographer Helmar Lerski, Transformation Through Light (1937), a photograph of which is presented below. Have a look on Google Images to see the changes wrought on the same face just through the use of light.

It is interesting to note the inclusion of photographers such as Paul Caponigro and Brett Weston in this exhibition as later examples of artists influenced by language of Modernism. While this may be partially true by the mid-1970s the mechanised vision of early Modernism (with its link to the indexicality of the image, its documentary authority and ability to express the individuality of the artist) had dissipated with the advent of the seminal exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape (International Museum of Photography at the George Eastman House, 1975). “The pictures were stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion.” These typologies, often shown in grids, “depicted urban or suburban realities under changes in an allegedly detached approach… casting a somewhat ironic or critical eye on what American society had become.” (Wikipedia) While the photographs by Weston and Caponigro do show some allegiance to Modernist Photography they are of an altogether different order of things, one that is not predicated on what the object is or what the artist says it is (its reality), but also, what else it can be.

Of course, this leads into more critical readings on the meaning of photographs that emerged in the late 1970s-80s. As Patrizia di Bello has insightfully written,

“John Tagg, in The Burden of Representation (1988), argues that the indexical nature of the photograph does not explain its meanings. “What makes the link between the pre-photographic referent and the sign is a discriminatory technical, cultural and historical process in which particular optical and chemical devices are set to work to organise experience and desire and produce a new reality – the paper image which, through further processes, may become meaningful in all sorts of ways.” Rather than being a guarantor of realism, the camera is itself an ideological construct, producing an all-seeing spectator and effacing the means of its production. Analyses of who has possessed the means to represent and who has been represented reveal that photography has been profoundly implicated in issues of political, cultural, and sexual domination. This area of investigation has especially drawn upon Michel Foucault’s (1926-84) reflections on the emergence of forms of knowledge; on the modern notion of the subject; and on practices of power which produce subjects actively participating in the dominant disciplinary order. Particularly influential have been his rejection of the notion of a pre-given self or human nature, and his insistence that every system of power and knowledge also creates possibilities of resistance. The role of critics then becomes the deconstruction of dominant assumptions within and about representations, to identify works embodying the possibility of resistance.”3

The camera as ideological construct. Photography as profoundly implicated in issues of political, cultural, and sexual domination. In other words who is looking, at what, what is being pictured or excluded, who has control over that image (and access to it), who understands the language of that representation and controls its meaning (this picturing of a version of reality), and who resists the dominant assumptions within and about its representations.

Modernist Photography does indeed have a lot to answer for.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Patrizia di Bello. “Modernsim and Photography,” on Answers.com website [Online] Cited 03/08/2012 no longer available online

2/ Ibid.,

3/ Ibid.,

Many thankx to the Currier Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Paul Caponigro (American, 1932-2024)

Two Pears, Cushing, ME

1999

Gelatin silver print

7 9/16 x 9 11/16 in

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Gift of Paul Caponigro, photographer

Captured from above, the still-life Two Pears, Cushing, ME by Paul Caponigro is composed of two pieces of fruit nestled in a wooden bowl. The oval bowl is centrally located in the horizontal composition and is surrounded by a black background. The composition is roughly symmetrical, except for the stems of the pears, which break the central axis and create a diagonal frame. The pears hold a complementary position with relation to each other, reminiscent of a yin-yang symbol.

The pears glow a brilliant white in stark contrast to the black background. The fruit seems impossibly smooth, as though carved from marble, with the subtlest of grays suggesting vaguely corporeal curves. The smooth texture is juxtaposed with the rough natural bark that lines the edge of the wooden bowl. The interior of the bowl shows the subtle patterns, striations and concentric rings, of the tree from which the bowl was carved. …

Context and Analysis

Though primarily known as a landscape photographer, Caponigro also focuses on still-life. One of his favourite subjects is fruit. Caponigro began producing dramatic, black-and-white images of apples and pears in the 1960s. Devoid of their characteristic colour, the close-up images become abstract studies in form and, more important, pattern.

Many of Caponigro’s fruit still-lifes from the 1960s focus on the marks and patterns on the skin of the fruit. This is particularly true in Galaxy Apple, New York (1964), a high-contrast image that highlights the natural white markings on the dark surface of an apple, creating an effect reminiscent of stars in the night sky. Documenting decay in fruit still-life pictures is a tradition dating back hundreds of years, as seen in such works as Balthasar Van der Ast’s 1617 oil painting Still Life with Fruit on a Kraak Porcelain Dish (Currier, 2004.15 ). Still-life compositions are often about the passage of time. In the late-career photograph Two Pears, Cushing, ME, Caponigro instead presents the fruit as near-perfect and timeless.

Connections

Caponigro studied with pioneering photographer Minor White, whose work is also represented in the Currier’s collection. White and Caponigro shared an interest in modernist techniques and in ways of conveying the passage of time by using the natural world as subject matter. White’s 1963 photograph Bird Lime and Surf, Point Lobos, CA (Currier, 1992.15.13, above) shows a rock spotted with bright white bird droppings, traces of the birds gathering and flying along the shoreline.

Jane Seney. “Two Pears, Cushing, ME,” on the Currier Museum of Art website Nd [Online] Cited 17/10/2024

Paul Caponigro (American, 1932-2024)

San Sebastian, New Mexico

1980

gelatin silver print

9 3/4 in. x 13 11/16 in. (24.77 x 34.77cm)

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Henry Melville Fuller Fund

Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993)

(Untitled) Tide Pool and Kelp

c. 1980

Gelatin silver print

10 9/16 x 13 11/16 in

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Gift from the Christian K. Keesee Collection

© The Brett Weston Archive

Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993)

(Untitled) Branches and Snow

c. 1975

Gelatin silver print

12 3/4 x 10 5/8 in

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Gift from the Christian K. Keesee Collection

© The Brett Weston Archive

Helmar Lerski (Swiss, 1871-1956)

Metamorphosis through Light #587

1935-1936

Vintage gelatin silver print

11 1/2 x 9 1/4 in

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Helmar Lerski (18 February 1871, Strasbourg – 19 September 1956, Zürich) was a photographer who laid some of the important foundations of modern photography. He focused mainly on portraits and the technique of photography with mirrors. Lerski concentrated on archetypal characteristics rather than on individual features, favouring extreme close-ups and tight cropping, and he became renowned for his experiments with multiple light sources.

Lerski was involved concurrently in the two major, emergent mediums of his time: film and photography. Born in Alsace in the then German city of Strausburg, he became involved in the theatre and, in 1896, moved to New York to pursue a career in acting, eventually working at the Irving Place Theater and later the German Pabst Theater. It was in this setting that Lerski first became aware of the unique visual effects achievable with stage lighting. Drawing from his acting experience, he began investigating photography as an artistic medium after meeting his wife, also a photographer. While photographing their colleagues, Lerski experimented with a series of portraits that severely manipulated the lighting effects. The resulting images formed a base for his later success in both commercial and art photography… This body of work upholds the artist’s declaration that “in every human being there is everything; the question is only what the light falls on.”

In 1937 he created his masterpiece, Transformation Through Light, on a rooftop terrace in Tel Aviv, in which he projected 175 different images of a single model, altered using multiple mirrors to direct intense sunlight towards his face at various angles and intensities. Siegfried Kracauer wrote about this series in his Theory of Film (Oxford University Press, 1960, p. 162):

“His model, he [Lerski] told me in Paris, was a young man with a nondescript face who posed on the roof of a house. Lerski took over a hundred pictures of that face from a very short distance, each time subtly changing the light with the aid of screens. Big close-ups, these pictures detailed the texture of the skin so that cheeks and brows turned into a maze of inscrutable runes reminiscent of soil formations, as they appear from an airplane. The result was amazing. None of the photographs recalled the model; and all of them differed from each other…

Out of the original face there arose, evoked by the varying lights, a hundred different faces, among them those of a hero, a prophet, a peasant, a dying soldier, an old woman, a monk. Did these portraits, if portraits they were, anticipate the metamorphoses which the young man would undergo in the future? Or were they just plays of light whimsically projecting on his face dreams and experiences forever alien to him? Proust would have been delighted in Lerski’s experiment with its unfathomable implications.”

Text from Wikipedia, Weimar Blog and Articles and Texticles websites

Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971)

Turbine, Niagara Falls Power Co.,

1928

Gelatin silver print

13 1/2 x 9 1/2 in

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Photo © Estate of Margaret Bourke-White/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

The Currier Museum of Art’s latest special exhibition traces the development of the modernist movement from the 1920s to its impact on artists today. Featuring more than 150 works displayed in three expansive galleries, A New Vision: Modernist Photography reflects the international nature of modernism, and includes American photographers such as Ansel Adams, Edward and Brett Weston, Margaret Bourke-White, Man Ray and Charles Sheeler, as well as European artists including Lotte Jacobi, László Moholy-Nagy, Helmar Lerski and Imre Kinszki…

[Marcus: Imre Kinszki (1901-1944) was a pioneer of modernist photography in Hungary, and a founder member of the group called Modern Hungarian Photographers. His son died in Buchenwald while he died on a death march to Sachsenhausen in 1944. See a moving video on YouTube where his daughter, who survived the ghetto, Judit Kinszki Talks About Her Father. The heartbreaking quotation below comes from the Articles and Texticles website which is no longer available online. It makes me very angry and very sad.

“In the ghetto we didn’t know anything about Auschwitz and what happened to those in forced labor service. It didn’t even occur to us that my father might not be alive. My mother and I went every day to the Keleti railroad station and went up to everybody who got off and asked them. Once my mother found a man who had been in the same group, and he remembered my father. He said that their car had been unhooked and the train went on towards Germany. They got off somewhere and went on foot towards Sachsenhausen – this was a death march. They spent the night on a German farm, in a barn on straw, and the man [who came back] said his legs had been so full of injuries that he couldn’t go on, and had decided that he would take his chances: he wormed himself into the straw. He did it, they didn’t find him, and that’s how he survived. He didn’t know about the others. We never found anyone else but this single man. So it’s clear that somewhere between this farm and Sachsenhausen everyone had been shot. But we interpreted this news in such a way that all we knew about him was that he would arrive sometime soon. We didn’t have news of my brother for a long time, then my mother found a young man who had worked with my brother. He told us that when they arrived in Buchenwald in winter, they were driven out of the wagon, and asked them what kind of qualifications they had. My brother told them that he was a student. This young man told us that the Germans immediately tied him up, it was a December morning, and they hosed him down with water just to watch him freeze to death. Those who didn’t have a trade were stripped of their clothes and hosed with cold water until they froze. I think that at that moment something broke in my mother. She was always waiting for my father, she refused to declare him dead even though she would have been eligible for a widow’s pension. But she waited for my father until the day she died. She couldn’t wait for my brother, because she had to believe what she had heard. Why would that young man have said otherwise?”]

Boris Ignatovich’s 1930s Tramway Handles and Margaret Bourke-White’s 1928 photo Turbine, Niagara Falls Power Co. [see below] showcase modernist images of isolated elements from the manmade world. While close-ups of nature, such as Brett Weston’s 1980 (Untitled) Tide Pool and Kelp, reveal striking abstract compositions that emphasise the repetition of patterns and dramatic contrast of light and shade. This new vision shared by modernist photographers makes form and composition as important as subject matter in their photographs.

“This exhibition illustrates the diversity of the modernist movement and its important contribution to the art of the 20th and 21st centuries,” said Kurt Sundstrom, curator of the exhibition. Adding, “Modernist photographers expanded the visual vocabulary of art – making everyday objects – from grass, drying laundry, machinery and lumber to details of the human body – subjects worthy of artistic interest.”

Contemporary New England photographers are still building upon the artistic language that their predecessors developed. Paul Caponigro, who lives in Cushing, Maine, Carl Hyatt of Portsmouth, New Hampshire and Arno Minkkinen of Andover, MA all clearly connect to modernism and are part of A New Vision.

A New Vision also explores the reciprocal influences among all media that shaped the modern art movement. Artists in the varied media shared a common vision; to illustrate this interconnectedness, paintings by Marsden Hartley, Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles Sheeler and Childe Hassam are paired with photographs in this exhibition.

Press release from the Currier Museum of Art website

Boris Ignatovich (Russian, 1899-1976)

Tramway Handles

1930s (printed 1955)

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 x 6 3/8 in

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Art © Estate of Boris Ignatovich/RAO, Moscow/VAGA, New York.

Boris Ignatovich, born in Lutsk, Ukraine in 1899, was a Soviet photographer and a member of the Russian avant-garde movement. Ignatovich began his career in 1918, first working as a journalist and a newspaper editor before taking up photography in 1923. In the early 1920s he worked for a number of publications, most notably, Bednota (Poverty), Krasnaya Niva (Red Field) and Ogonyok. Ignatovich’s first photographic success was a documentary series about villagers in the Ramenskoe’s Workers’ settlement, which coincided with the first 5-year plan after Stalin’s victory. Ignatovich tried to alter the traditional format of documentary photography by using very low and very high unconventional angles, developing new perspectives, and including birds-eye constructions, which rendered the landscape as an abstract composition. In 1926 Ignatovich participated at the exhibition of the Association of Moscow Photo-Correspondents, and later became one of its leaders. In 1927, he photographed power plants and factories for Bednota and developed close association with Alexander Rodchenko, as they photographed for Dajosch together. Ignatovich’s famous photo stories also included the first American tractors in the USSR and aerial photographs of Leningrad and Moscow. In 1928, Ignatovich participated in the exhibition 10 Years of Soviet Photography, in Moscow and Leningrad, which was organized by the State Academy of Artistic Sciences. Due to his companionship with Rodchenko, Ignatovich was greatly influenced by his style and unconventional techniques. Both became members of the distinguished Oktiabr, the October group, which was a union of artists, architects, film directors, and photographers. In February of 1930, a photographic section of the October group was organised. Rodchenko was the head of the section and wrote its program. Other members include Dmitrii Debabov; Boris, Ol’ga, and Elizaveta Ignatovich; Vladimir Griuntal’; Roman Karmen; Eleazar Langman; Moriakin; Abram Shterenberg; and Vitalii Zhemchuzhnyi. The October group, whose styles favored fragmentary techniques and the distortion of images in an avant-garde manner, captured the idea of a world in dynamic form and rhythms.

First general October exhibition opened at Gorky Park, a park of culture and rest named after Gorky in Moscow. The photography section, organised by Rodchenko and Stepanova, includes the magazine Radioslushatel, designed by Stepanova and illustrated with photographs by Griuntal, Ignatovich, and Rodchenko. When Rodchenko was expelled from the October group for his formalist photography, Ignatovich took over as head of the photographic section of the group until the group was dissolved in 1932 by governmental decree. Apart from October, Ignatovich worked on documentary films from 1930 to 1932. As a movie cameraman, Ignatovich worked on the first sound film, Olympiada of the Arts. After 1932 he began to pioneer ideas such as the theory of collectivism in photojournalism at the Soyuzfoto agency where he developed specific rules and laws of photography, so much so that the photographers working under him were obliged to follow and jointly credit their work to Ignatovich by signing their photographs “Ignatovich Brigade.” Ignatovich participated in 1935 Exhibition of the Work of the Masters of Soviet Photography as well as the All-Union Exhibition of Soviet photography at the State Pushkin Museum in 1937. During the 1930s, Ignatovich also contributed photographs to the USSR In Construction, and in 1941, worked as a war photo correspondent on the front. After the War, Ignatovich concentrated on landscape and portraiture, experimenting with the use of symbols, picture captions, and ideas of collectivism, particularly at the Soyuzfoto agency where he continued to work as a photojournalist until he died in 1976.

Text from the Nailya Alexander Gallery website

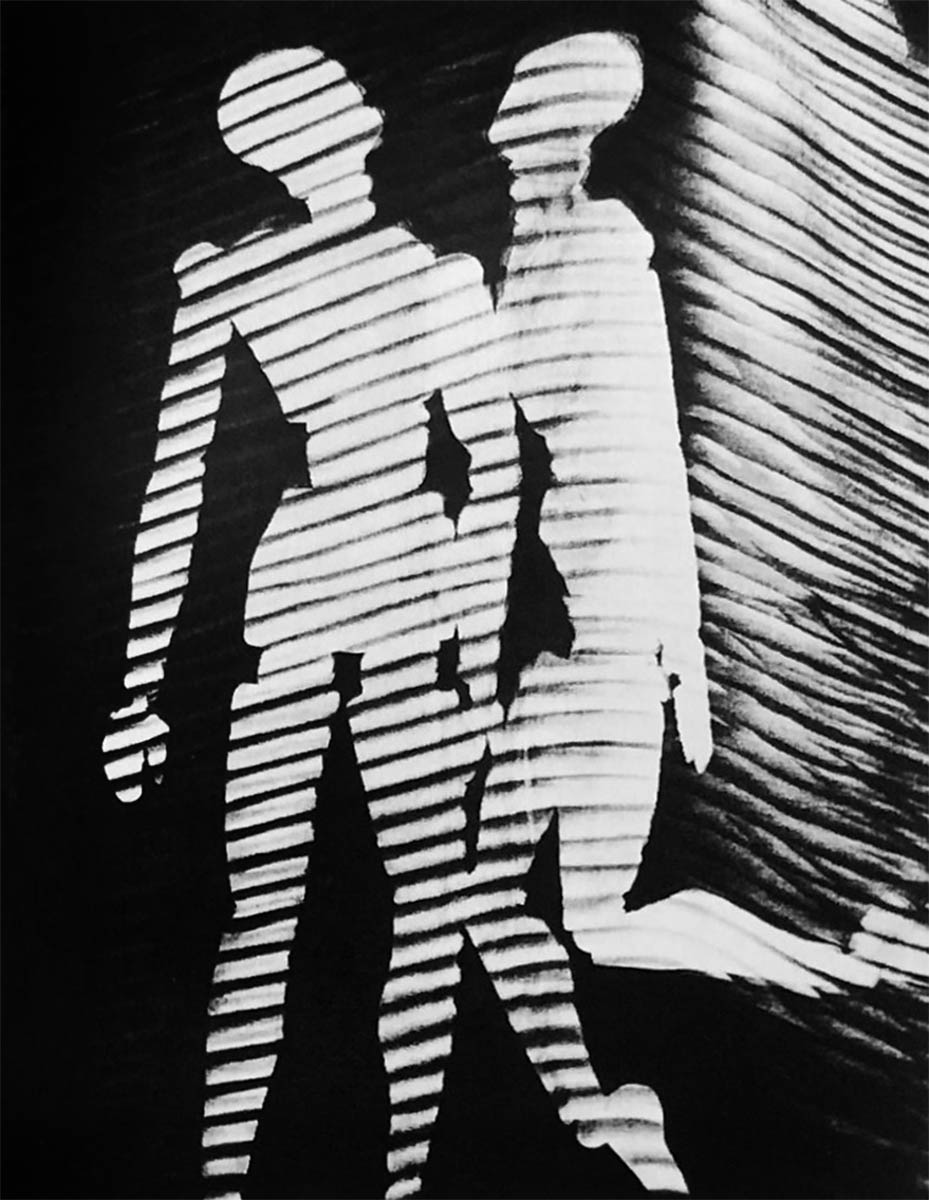

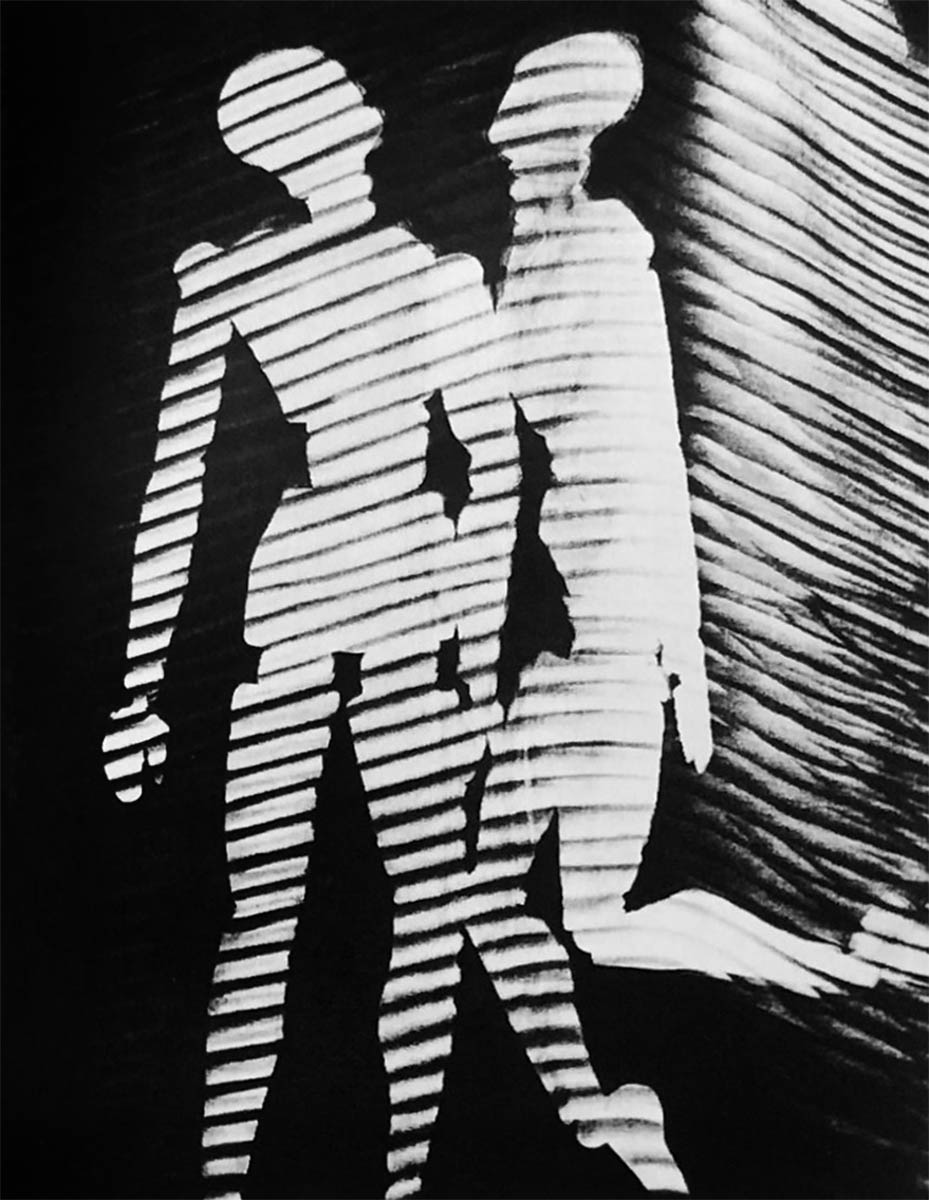

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Mr. and Mrs. Woodman

c. 1930

Rayograph

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Paul Strand (American, 1890-1976)

Akeley Motion Picture Camera

1923, printed 1976

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 in. x 7 5/8 in. (24.13 x 19.37cm)

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Gift of Edith Vallarino

The Currier’s Akeley Motion Picture Camera is one of the machine-inspired photographs that distinguished Strand early in his career. In the summer of 1922 Strand purchased an Akeley motion picture camera for the purpose of making freelance newsreel and documentary films. Fascinated by the camera’s complex construction, he made it the subject of a series of close-up photographs. In these works, Strand explored the expressive possibilities of abstract form and composition while simultaneously celebrating the technological achievement of the dawning machine age.

Avoiding anecdotal associations that might arise from showing the motion picture camera within a larger pictorial context, Strand adopts a close-up view that makes it difficult to identify the machine or its purpose. The resulting composition is a nearly abstract presentation that expresses the spirit of all machinery rather than the facts of a particular model of motion picture camera. Here the viewer is presented with an assemblage of interlocking parts, each polished and gleaming. Although it is unclear as to each part’s specific function, one cannot help but admire the precision with which each is made and fitted together. Taking the viewer’s gaze past an array of complex shapes and forms -disks, cylinders, spiral springs, and others more organic in nature- Strand points to the ingenuity of the engineers, draftsmen, and manufacturers behind their making. Like the Precisionist paintings of Strand’s friend Charles Sheeler, the image is one of newness, cleanliness, and logical rigor. Epitomizing the efficiency and purity of the modern machine, Akeley Motion Picture Camera becomes a metaphor for modernism itself, and a key to understanding Strand’s own philosophy as an artist.

Anonymous. “Akeley Motion Picture Camera,” on the Currier Museum of Art website Nd [Online] Cited 17/10/2024

Lotte Jacobi (American, 1896-1990)

Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, Berlin

1932

Gelatin silver print

9 1/2 in. x 7 1/2 in. (24.13 x 19.05cm)

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard Thorner in honor of Kurt Sundstrom

Emerging out of the enveloping darkness, a large church stands out from the background with a sense of imposing volume. The burned-in whites of the street lamps, the lights of the cars, and the bright reflections on the rain-streaked streets are all emphasised by the photographer’s use of a long exposure. Looking carefully, one can notice the trail of light left by a moving car, which also suggests a long exposure.

Photographer Lotte Jacobi chose to angle her camera slightly downward. In doing so, she enlarged the foreground space and enhanced the scale of the church by lowering the horizon line and emphasising the leading lines of the streetcar tracks. The massive medieval shapes of the church contrast in form and theme with the modernity of the lamps, cars, and streetcar tracks.

Context and Analysis

Jacobi is best known for her expressive portraits and also for her abstract “photogenic” series, but she photographed other subjects as well. Her body of work includes cityscapes of Berlin, Germany, her native city, and photographs documenting her trip to the Soviet Union in 1932-33.

Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, Berlin is a modernist experiment with the expressive power of nighttime photography. Jacobi’s use of dramatic light and shadows recalls Brassaï’s nocturnal photographs of Paris from the same era. Jacobi would later explain: “I am involved in seeing.” In this photograph she created a dramatic record of her vision.

Although its architecture appears to be from the Middle Ages, with stone towers, arches, and stained-glass windows, Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church was actually built in the late 1800s in the Romanesque Revival architectural style. Designed by architect Franz Schwechten, it was constructed between 1891 and 1906. The church was dedicated to Kaiser Wilhelm I by his grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II. Wilhelm I had achieved the unification of Germany, becoming the first German emperor. After Germany’s loss in World War I, Wilhelm II abdicated, and the German Empire was replaced by the Weimar Republic.

Eleven years after Jacobi made this photograph, the church was irreparably damaged by Allied bombing in World War II, one of many culturally significant buildings destroyed in that war. In the early 1960s a modern church was built around the site, preserving the ruins of the old structure.

Martin Fox. “Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church, Berlin,” on the Currier Museum of Art website Nd [Online] Cited 17/10/2024

Brett Weston (American, 1911-1993)

(Untitled) Fremont Bridge, Portland

1971

Gelatin silver print

13 1/4 x 10 1/2 in

Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire. Gift from the Christian K. Keesee Collection

© The Brett Weston Archive

Currier Museum of Art

150 Ash Street, Manchester

New Hampshire 03104

Phone: 603.669.6144

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Sunday 10am – 5pm

Closed Mondays and Tuesdays

The Currier Museum of Art website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.