Exhibition dates: 1st October, 2014 – 18th January, 2015

Artists: Andrew Blythe, Kellie Greaves, Julian Martin, Jack Napthine, Lisa Reid, Martin Thompson and Terry Williams

Curator: Joanna Bosse

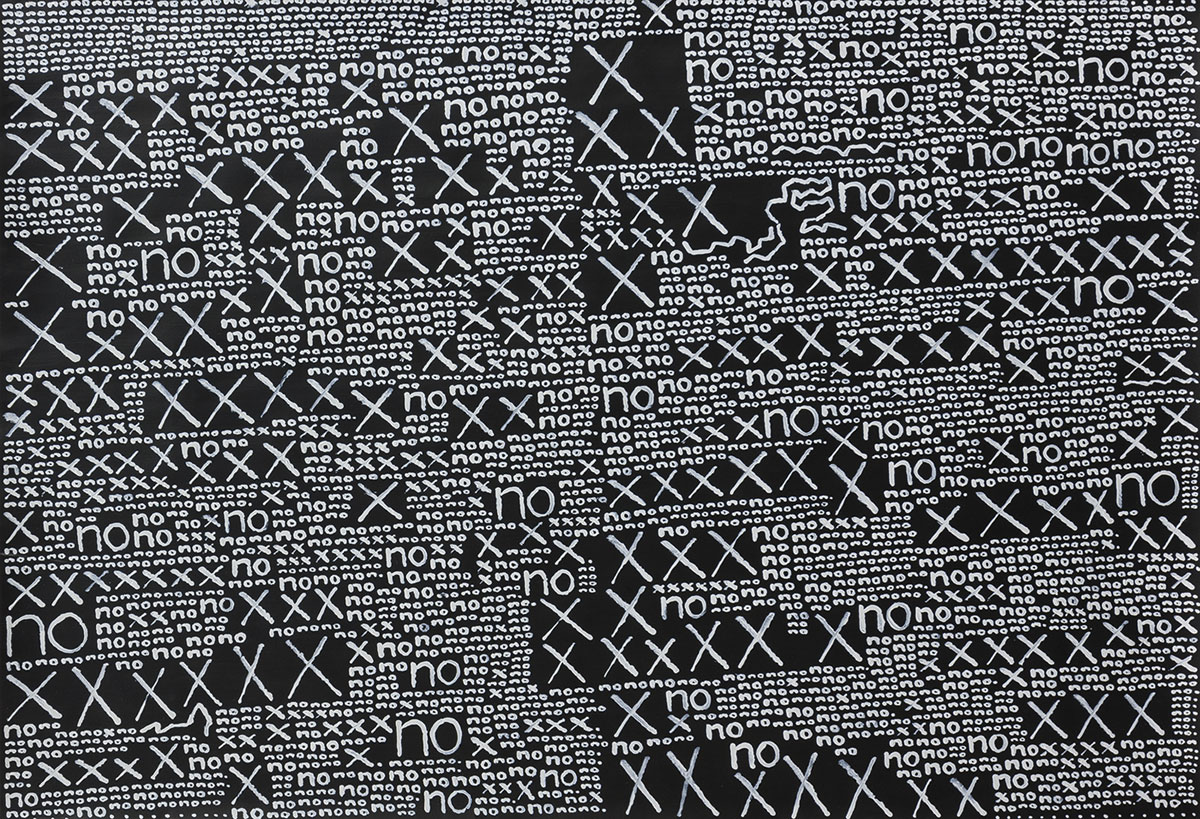

Martin Thompson (New Zealand, b. 1956)

Untitled

2014

Ink on paper

52.5 x 105cm

Courtesy the artist and Brett McDowell Gallery, Dunedin

This is a gorgeous exhibition at The Ian Potter Museum of Art. Walking through the show you can’t help but have a smile on your face, because the work is so inventive, so fresh, with no pretension to be anything other than, well, art.

There are big preconceptions about ‘Outsider art’, originally art that was made by institutionalised mentally ill people, but now more generally understood as art that is made by anyone outside the mainstream of art production – “artworks made by folk artists and those who are self-taught, disabled, or on the edges of society” who are disenfranchised in some way or other, either by their own choice or through circumstance or context.

Outsider art promotes contemporary art while still ‘tagging’ the artists as “Outsider” – just as you ‘tag’ a blog posting so that a search engine can find a specific item if it is searched for online. It is a classification I have never liked (in fact I abhor it!) for it defines what you are without ever understanding who you are and who you can become – as an artist and as a human being. One of the good things about this exhibition is that it challenges the presumptions of this label (unfortunately, while still using it).

As Joanna Bosse notes in her catalogue essay, “Most attempts to define the category of Outsider art include caveats about the elasticity of borders and the impact of evolving societal and cultural attitudes… The oppositional dialectic of inside/outside is increasingly acknowledged as redundant and, in a world marked by cultural pluralism, many question the validity of the category.”1 Bosse goes on to suggest that, with its origins in the term art brut (the raw and unmediated nature of art made by the mentally ill), Outsider art reinforces the link between creativity, marginality and mental illness, proffering “the notion of a pure form of creativity that expresses an artist’s psychological state [which] is a prevailing view that traverses the divergent range of creative practice that falls under the label.”2

The ambiguities of art are always threatened by a label, never more so than in the case of “Outsider art”. For example, how many readers who visited the Melbourne Now exhibition at NGV International and saw the magnificent ceramic cameras by Alan Constable would know that the artist is intellectually disabled, deaf and nearly blind. Alan holds photographs of cameras three inches away from his eyes and scans the images, then constructs his cameras by feel with his hands, fires them and glazes them. The casual viewer would know nothing of this backstory and just accepts the work on merit. Good art is good art no matter where it comes from. It is only when you enquire about the history of the artist – whether mainstream or outsider – that their condition of becoming (an artist) might affect how you contextualise a work or body of work.

Bosse makes comment about the rationale for the exhibition: “The decision to focus on artists’ engagement with the exterior, everyday world was to counter one of the common assumptions about artists in this category – that they are disconnected from society and that their work is solely expressionistic, in that it relates almost exclusively to the self and the expression of the artist’s emotional inner life.”3 Bosse agrees with the position that to simply eliminate the designation would be a different kind of marginalisation – “one where the unique world view and specific challenges the individual faces would become lost in a misguided attempt at egalitarianism.”4

As chair of a panel session at the international conference Contemporary Outsider Art: The Global Context, 23-26th October at The University of Melbourne, curator Lynne Cooke also sees the classification “Outsider” as valuable, for “Outsider art is the condition that contemporary art wants to be” – that is imaginative, free, intuitive, visceral and living on the edge. She sees contemporary art as having run up the white flag leaving Outsider art – however you define that (not the white, middle class male establishment, and belonging to the right galleries) – to be the vanguard, the new avant-garde.5 The exhibition catalogue concludes with her observation that, while current curatorial strategies breakdown the distinctions between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ – making significant headway concerning stigmatisation – these might have the effect of loosing what she describes as the “‘unique and crucial agency’ that this art has to challenge the ‘monocultural frame’.”6 These artists positions as ‘circuit breakers’, holding counter culture positions, may be threatened as their work is made ready for market, especially if they have little knowledge of it themselves.

And there’s the rub, right there. On the one hand Outsider art wants to be taken seriously, the people promoting it (seldom the artists) want it to be shown in mainstream galleries like the National Gallery of Victoria, and so it should be. Good art is good art not matter what. But they also want to have their cake and eat it too; they want to stand both inside and outside the frame of reference.7 In other words, they promote Outsider art within a mainstream context while still claiming “marginal” status, leveraging funding, philanthropy, international conferences and standing in the community as evidence of their good work. And they do it very successfully. Where would we be without fantastic organisations such as Arts Project Australia and Arts Access Victoria to help people with a disability make art? Can you imagine the Melbourne Art Fair without one of the best stands of the entire proceedings, the Arts Project Australia stand? While I support them 100% I am playing devil’s advocate here, for I believe it’s time that the label “Outsider art” was permanently retired. Surely, if we live in a postmodern, post-human society where there is no centre and no periphery, then ‘other’ can occupy both the centre and the margins at one and the same time WITHOUT BEING NAMED AS SUCH!

[Of course, naming “Outsider art” is also a way of controlling it, to have agency and power over it – the power to delineate, classify and ring fence such art, power to promote such artists as the organisations own and bring that work to market.]

Getting rid of the term Outsider art is not a misguided attempt at egalitarianism as Joanna Bosse proposes, for there will always be a narrative to the work, a narrative to the artist. The viewer just has to read and enquire to find out. Personally, what I find most inspiring when looking at this art is that you are made aware of your interaction with the artist. The work is so immediate and fresh and you can feel the flowering of creativity within these souls jumping off the page.

For any artist, for any work, what we must do is talk about the specific in relation to each individual artist, in relation to the world, in relation to reality and resist the temptation to apply any label, resist the fetishisation of the object (and artist) through that label, absolutely. This is the way forward for any art. May the nomenclature “outsider” and its discrimination be gone forever.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Bosse, Joanna. Everyday imagining: new perspectives on Outsider art. Catalogue essay. The Ian Potter Museum of Modern Art.

2/ Ibid.,

3/ Ibid.,

4/ Ibid.,

5/ Cooke, Lynne. Senior Curator, Special Projects in Modern Art, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. My notes from the panel session “Outsider Art in the Centre: Museums and Contemporary Art,” at Contemporary Outsider Art: The Global Context, 23-26th October at The University of Melbourne.

6/ Cooke, Lynne. “Orthodoxies undermined,” in Great and mighty things: Outsider art from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz collection. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2013, p. 213 quote in Bosse, Joanna, op. cit.,

7/ An example of this can be seen in the launch of the new magazine artsider – “Arts Access Victoria in Partnership with Writers Victoria invites you to the Launch of artsider, a magazine devoted to outsider art and writing.” What a clumsy title that seeks to have a foot in both camps. Email received from Arts Access Victoria 19/11/2014.

Many thankx to The Ian Potter Museum of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

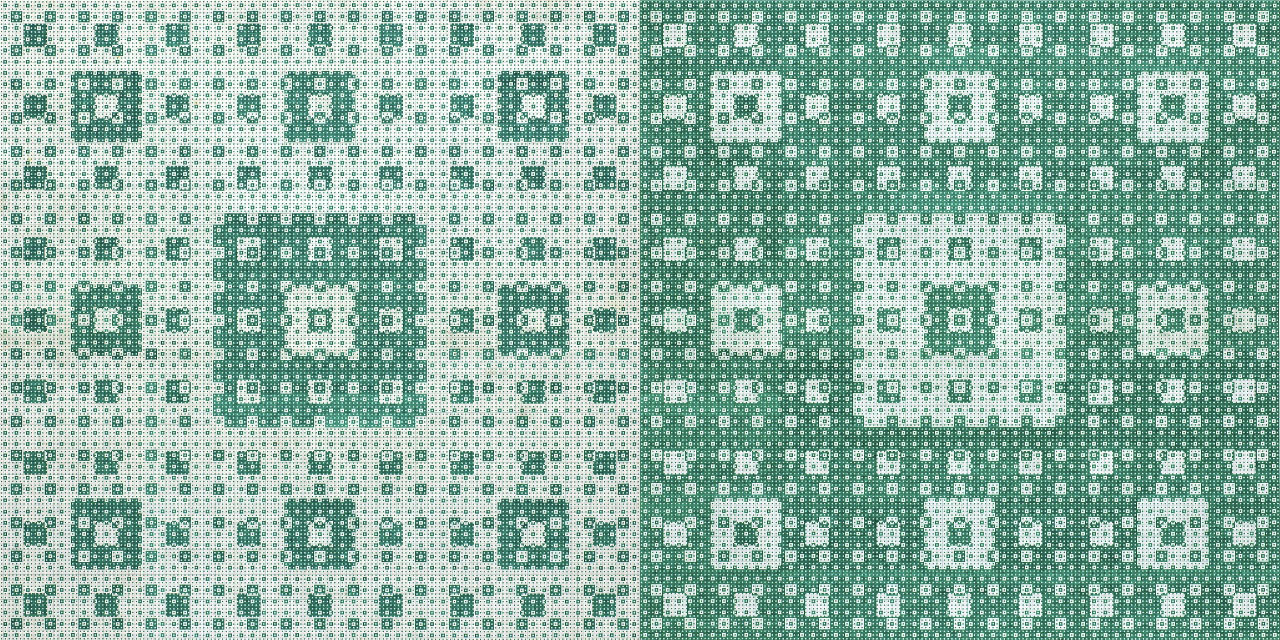

Andrew Blythe (New Zealand, b. 1962)

Untitled

2012

Synthetic polymer paint on paper

88 x 116cm

Courtesy the artist and Tim Melville Gallery, Auckland

Terry Williams (Australian, b. 1952)

Stereo

2011

Vinyl fabric, cotton, stuffing and fibre-tipped pen

21 x 43 x 14cm

Private collection, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist and Arts Project Australia, Melbourne

Terry Williams (Australian, b. 1952)

Telephone

2011

Fabric, cotton, stuffing and fibre-tipped pen

18 x 13 x 20cm

Private collection, Melbourne. Courtesy the artist and Arts Project Australia, Melbourne

An exhibition of Australian and New Zealand ‘Outsider’ artists which challenges a key existing interpretation of the genre will be presented at the Potter Museum of Art at The University of Melbourne, from 1 October 2014 to 15 January 2015. Everyday imagining: new perspectives on Outsider art, features the work of artists Andrew Blythe, Kellie Greaves, Julian Martin, Jack Napthine, Lisa Reid, Martin Thompson and Terry Williams.

The term ‘Outsider art’ was coined by British art historian Roger Cardinal in 1972 expanding on the 1940s French concept of art brut – predominantly artworks made by the institutionalised mentally ill – to include artworks made by folk artists and those who are self-taught, disabled, or on the edges of society. The work of Outsider artists is often interpreted as expressing a unique inner vision unsullied by social or cultural influences. Everyday imagining: new perspectives on Outsider art counters this view by presenting contemporary Outsider artists whose works reveal their proactive engagement with the everyday world through artworks that focus on day-to-day experiences.

Curator Joanna Bosse says the exhibition questions a key interpretive bias of Outsider art that is a legacy of its origins in art brut.

“The association with an interior psychological reality that is unsullied by social or cultural influences remains deeply embedded within the interpretations of Outsider art today, and can lead audiences to misinterpret the agency and intention of the artist. Everyday imagining: new perspectives on Outsider art questions this key interpretive bias, and presents the work of Australian and New Zealander outsider artists that demonstrate a clear and proactive engagement with the world. The work of artists Andrew Blythe, Kellie Greaves, Julian Martin, Jack Napthine, Lisa Reid, Martin Thompson and Terry Williams reveals their blatant interest in the here and now,” Ms Bosse said.

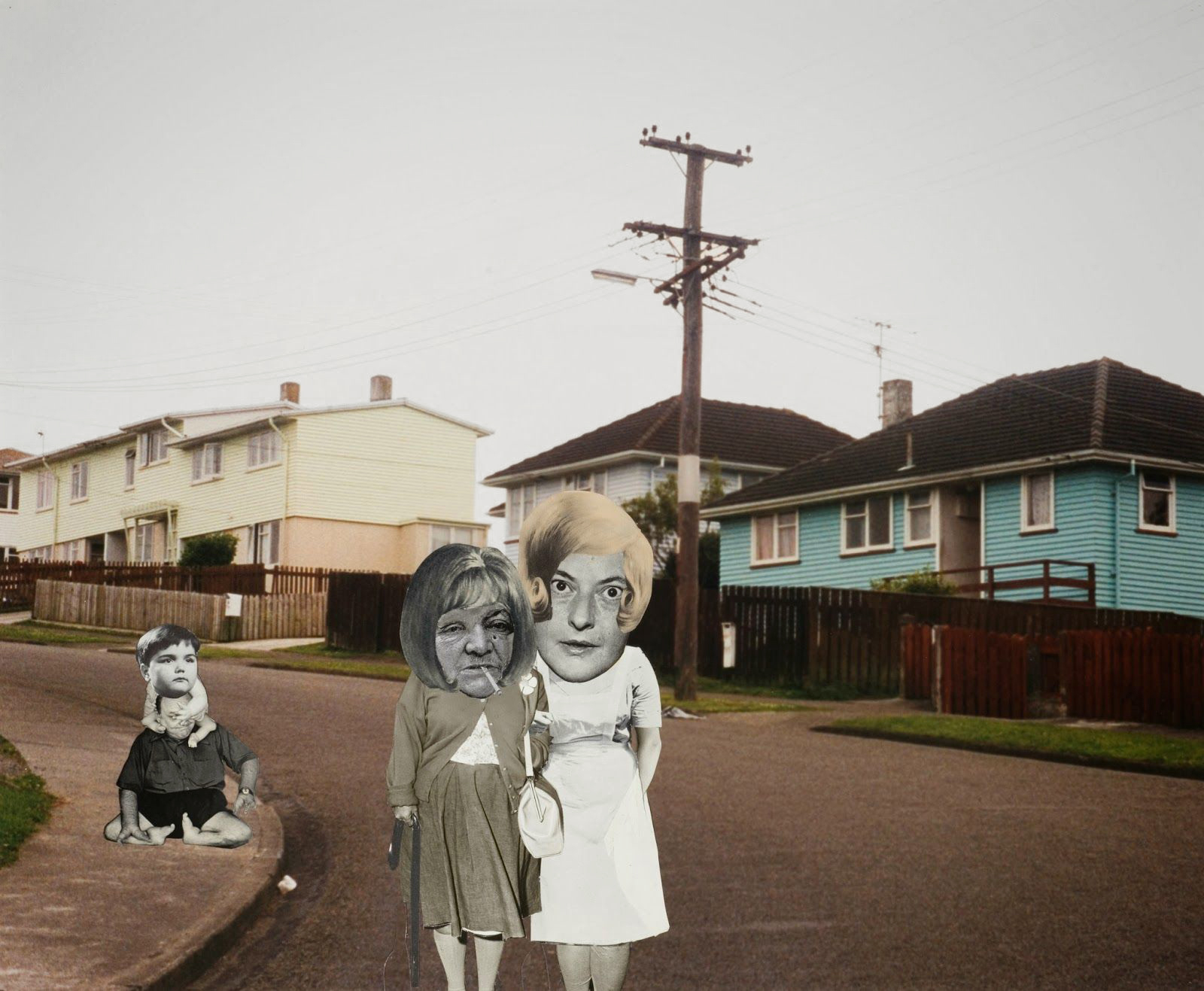

Terry Williams’ soft fabric sculptures of everyday items such as fridges, cameras and clocks convey his keen observation of the world and urgent impulse to replicate what is meaningful through familiarity or fascination. Kellie Greaves’ paintings are based on book cover illustrations with the addition of her own compositional elements and complementary tonal colour combinations. The traditional discipline of life-drawing provides Lisa Reid with a structure to pursue her interest in recording the human figure. Her pen and ink drawings are carefully observed yet intuitive renderings.

Jack Napthine produces drawn recollections of his past and present daily life in the form of visual diaries. Light fittings from remembered environments feature prominently as do doors with multiple and varied locks. Napthine’s work has a bold economy of means; he uses thick texta pen to depict simplified designs accompanied by text detail that often records the names of friends and family.

The work of Martin Thompson and Andrew Blythe also displays a similarly indexical approach. Both artists produce detailed repetitive patterns that are borne out of a desire for order and control. Thompson uses large-scale grid paper to create meticulous and intricate geometric designs whereas Blythe uses select motifs – the word ‘no’ and the symbol ‘x’ – to fill the pictorial plane with dense yet orderly markings that result in graphic and rhythmic patterns.

“In the last decade in particular there has been much debate about the term ‘outsider art’: who does it define? What are the prerequisite conditions for its production? What is it outside of, and who decides? This exhibition doesn’t seek to resolve these ambiguities or establish boundaries, but looks beyond definitions to challenge a key assumption underlying contemporary interpretations of outsider art,” Ms Bosse said.

Everyday imagining: new perspectives on Outsider art is held in conjunction with the international conference Contemporary Outsider art: the global context, presented Art Projects Australia and The University of Melbourne and held 23-26 October at The University of Melbourne. The conference proposes an inter-disciplinary exploration of the field, drawing on the experience and knowledge of Australian and international artists, collectors, curators and scholars.

Press release from The Ian Potter Museum of Art

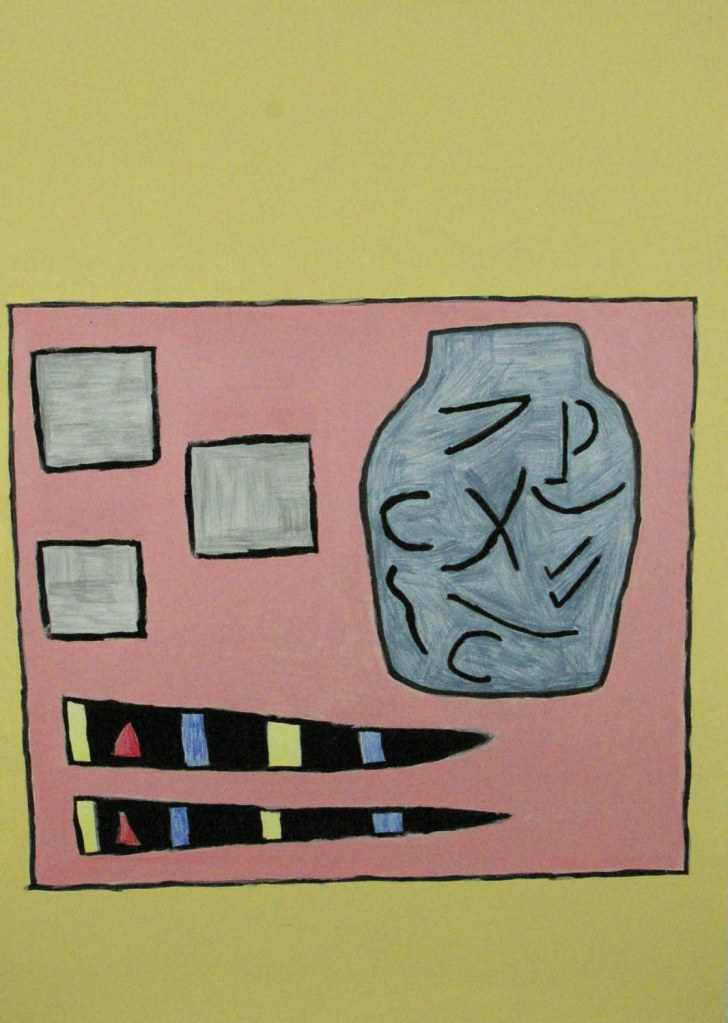

Julian Martin (Australian, b. 1969)

Untitled

2011

Pastel on paper

38 x 28cm

Courtesy the artist and Arts Project Australia, Melbourne

Kelly Greaves

My little Japan

2010

Synthetic polymer paint on paper

59.4 x 42cm

Courtesy the artist and Art Unlimited, Geelong

Jack Napthine (Australian, b. 1975)

Untitled

2013

Fibre-tipped pen on paper

59.4 x 42cm

Courtesy the artist and Art Unlimited, Geelong

Jack Napthine (Australian, b. 1975)

Untitled

2013

Fibre-tipped pen on paper

42 x 59.4cm

Courtesy the artist and Art Unlimited, Geelong

Lisa Reid (Australian, b. 1975)

Queen of hearts

2010

Pencil on paper

35 x 25cm

Courtesy the artist and Arts Project Australia, Melbourne

The Ian Potter Museum of Art

The University of Melbourne,

Corner Swanston Street and Masson Road

Parkville, Victoria 3010

Opening hours: Tuesday – Saturday 11am – 5pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.