Exhibition dates: 30th October, 2021 – 20th February, 2022

Image left: Greg Weight

Rosalie Gascoigne (detail)

1993

Gelatin silver photograph on paper

Image: 45.5 x 35.6cm

Sheet: 50.4 x 40.4cm

National Portrait Gallery, Australia

Gift of Patrick Corrigan AM 2004. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program.

© Gregory Weight/Copyright Agency, 2021

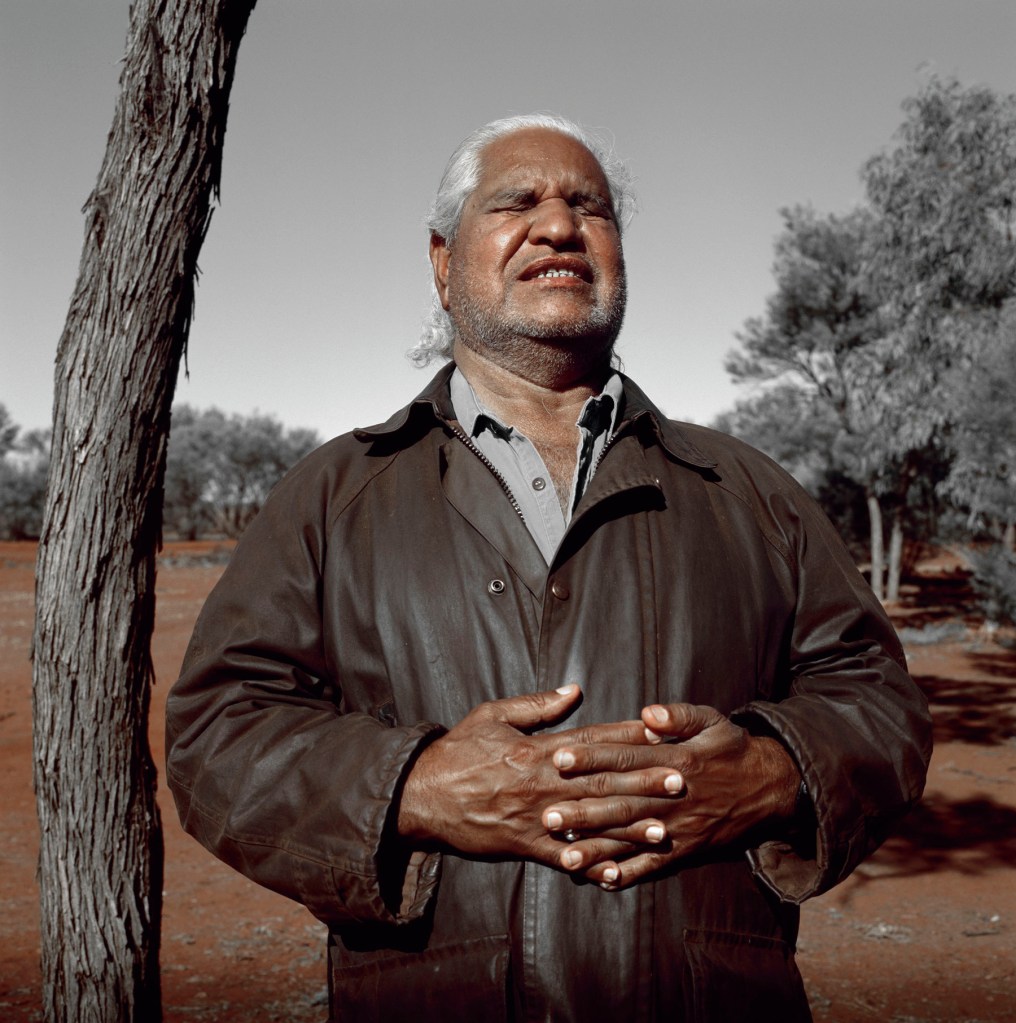

Image right: Jules Boag

Portrait of Lorraine Connelly-Northey (detail)

Courtesy of Jules Boag

© Jules Boag

Synergy. Now’s there’s an interesting word. It means “the interaction or cooperation of two or more organisations, substances, or other agents to produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate effects.” It derives from mid 19th century: from Greek sunergos ‘working together’, from sun- ‘together’ + ergon ‘work’. Thus, this glorious exhibition brings together two artists metaphorically “working together” under the Australian sun… even as they are separated by culture, location, time and space.

Their work comes together in a confluence of ideas of approximately equal width – one grounded in stories of family and Country thousands of years old, the artist investigating post-colonial settlement and the industrial world and interpreting Australian Indigenous objects of ritual and culture; the other not so much grounded but playing with Western ideas of pattern and randomness, belonging, and the metaphysical space of the landscape of the Monaro, in the southwest of New South Wales. Both points of view are equally valid and have important things to say about our various relationships to the land (both Indigenous and colonial) and the “creation” of a contemporary Australian national identity.

Both artists use found objects in their work, but as Russell-Cook points out, “I think that what unites the two artists is the shared materials they use, but not a ‘shared-use of materials.’ They are both fascinated by the artistic possibilities of found objects, but they use those materials to tell contrasting stories.” Connelly-Northey uses her experience of living on Country and her gleaning of discarded objects in Country to gather up the threads of her multiple heritages and Aboriginal custodianship of the land to picture – through the merging of organic and inorganic forms – the disenfranchisement of her people but also to celebrate their deep roots in Country. Gascoigne on the other hand is the more ethereal of the two artists, concerned as she is with light, land, spirit of place and the rightness of materials being used. Hers is a very structured and formal art practice grounded in her training in the Japanese art of ikebana and her understanding of Minimalism. Sympathetically, through their individual creativity both artists transmute (to change in form, nature, or substance) the reality of the materials they work with, the raw material of experience transmuted into stories. As Rozentals and Russell-Cook observe, “Both Connelly-Northey and Gascoigne’s work is defined by, and yet transcends, its sense of materiality.”

Two things jar slightly. Connelly-Northey is ‘a bit anxious’ that her Indigenous originality won’t be recognised and that “I’ve worked too hard for people to think I borrowed it all from Rosalie. Our use of corrugated iron is the only thing we have in common.”

Connelly-Northey can have no fear that her Indigenous originality won’t be recognised because every pore of her strong work speaks to her cultural being. Her spiky, brittly astringent, barbed and feathered works take you to Country, posing the viewer uncomfortable questions about “soft” assertions of history and the hard reality of contemporary Indigenous life: metal as string, desecration of sacred sights, barbed wire handles, “hunters and gatherers whose remains have been upturned by settled Australian societies.” She weaves her stories well.

If the second statement has not been taken out of context, it shows a heap of unnecessary defensive aggression by Connelly-Northey towards Gascoigne’s work. It’s a silly, uninformed statement which hints at a lack of confidence in the strength of her own work. Patently, their use of corrugated iron is not the only thing they have in common.

Both speak towards a love of the Australian land whether from an ancient Aboriginal custodianship perspective or from a Western colonial perspective. Both use scavenging, gathering and gleaning in order to recycle the refuse of society in their art making, Connelly-Northey using weaving to bring together that which is disparate; Gascoigne assembling her formal compositions with an attention to order and randomness. Both artists love to move through the space and time of the land, exploring its idiosyncrasies, “disassociating objects from their original function via a system of obsessive collecting and gathering, while simultaneously reflecting their individual experiences of being immersed in the bush environment.” As Rozentals and Russell-Cook comment, “Despite their careers having been separated by time, and coming from vastly different backgrounds, in both artists we see a singular vision that is immediately recognisable, and unmistakably them. And yet there is a sympathetic connection between their practices that is undeniable.”

Conjoined by more than corrugated iron, more than land, air and clan, their common union is the journey of two creative souls on that golden path of life and the connection of those souls to the cosmos.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

All of the images unless otherwise stated are by Marcus Bunyan. © Marcus Bunyan, the artists and the National Gallery of Victoria. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Although they are often compared, Gascoigne and Connelly-Northey are separated conceptually and chronologically. For a start, despite being two Australian women artists working with landscape, they never met. This fact is less surprising when one remembers that Connelly-Northey’s practice only matured towards the later stages of Gascoigne’s life. Gascoigne came to prominence late and rapidly, with her first exhibition in 1974, when she was fifty-seven years old, and it was only eight years later that she represented Australia at the Venice Biennale. Connelly-Northey started exhibiting seriously in the mid-nineties, shortly before Gascoigne passed away in 1999. However, Connelly-Northey has herself commented on a nuanced relationship to the historical comparison with Gascoigne, pointing out in a recent conversation with Jeremy Eccles that “I’ve worked too hard for people to think I borrowed it all from Rosalie. Our use of corrugated iron is the only thing we have in common.” In some ways, then, the fact they never met may have been fortuitous, with both artists driven to probe their subject matter in distinct and complete ways. …

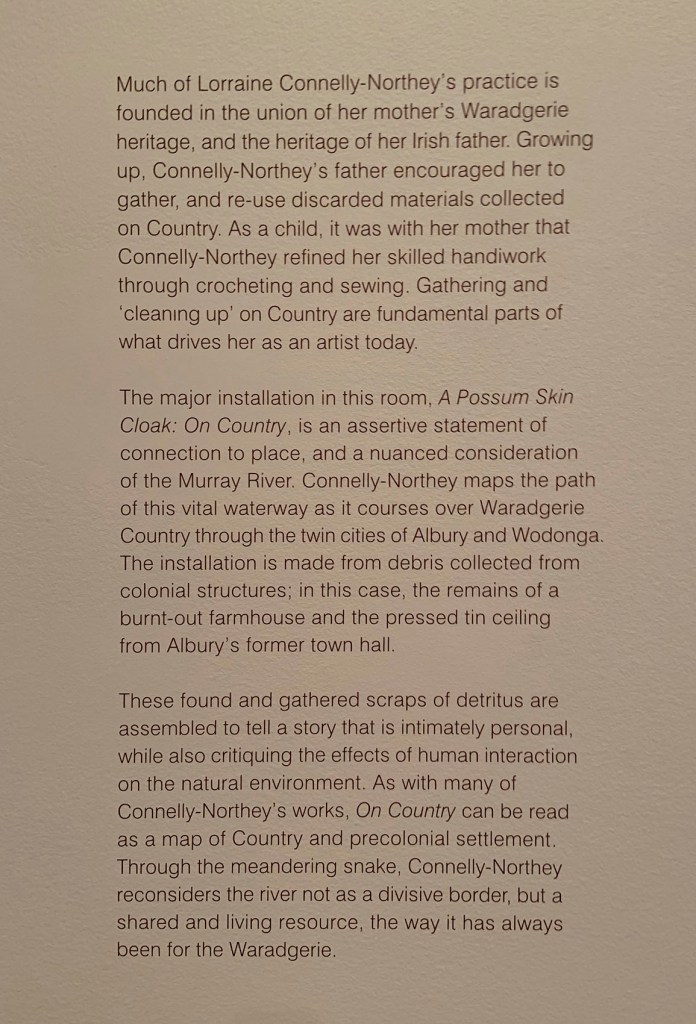

Surrounding built and natural environments are a recurring prompt for Connelly-Northey, who often merges organic and inorganic forms. She investigates the intricate dilemmas and complexities that arise when two cultures meet. Co-curator Myles Russell-Cook explains that the artist “is using her work to explore the connection between her multiple heritages, as well as her experience living on Country. Take her work On Country, 2017; in that installation, Connelly-Northey explores the relationship between the twin cities of Albury and Wodonga, depicting the river a living being, which she imagines as a snake repurposed out of chicken wire and rusted and industrial scrap metal. It’s a dioramic representation of the landscape, but it is also so embedded with references to Aboriginal custodianship of Country.” As a result, Russell-Cook argues, Connelly-Northey proposes “a really different way of being in Australian landscape.”

Beyond these conceptual and chronological differences, however, Russell-Cook points out that “I think that what unites the two artists is the shared materials they use, but not a ‘shared-use of materials.’ They are both fascinated by the artistic possibilities of found objects, but they use those materials to tell contrasting stories.” As Rozentals notes, for Gascoigne, “the objects had to be just right – what she collected, for instance, with shells. There could be no cracks and they had to be of a particular colour and a particular shine; she would collect the feathers of different species of birds from particular locations.” For Russell-Cook, “At the heart of what Connelly-Northey does, is the act of cleaning up Country: going out and collecting up bits of discarded and refuse machinery, and then working with that to create customary forms. She makes a lot of possum-skin cloaks, narrbong-galang, which are a type of string bag, as well as koolimans (coolamons), lap-laps, and other types of cultural objects … she repurposes them to create a juxtaposition between cultural memories.”

Extract from Rose Vickers. “Found and Gathered: Lorraine Connelly-Northey and Rosalie Gascoigne,” in Artist Profile, Issue 57, 2021 [Online] Cited 01/02/2022

Installation view of the exhibition Found and Gathered at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia

Photo: Tom Ross NGV

Wall text from the exhibition

Entrance to the exhibition Found and Gathered at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

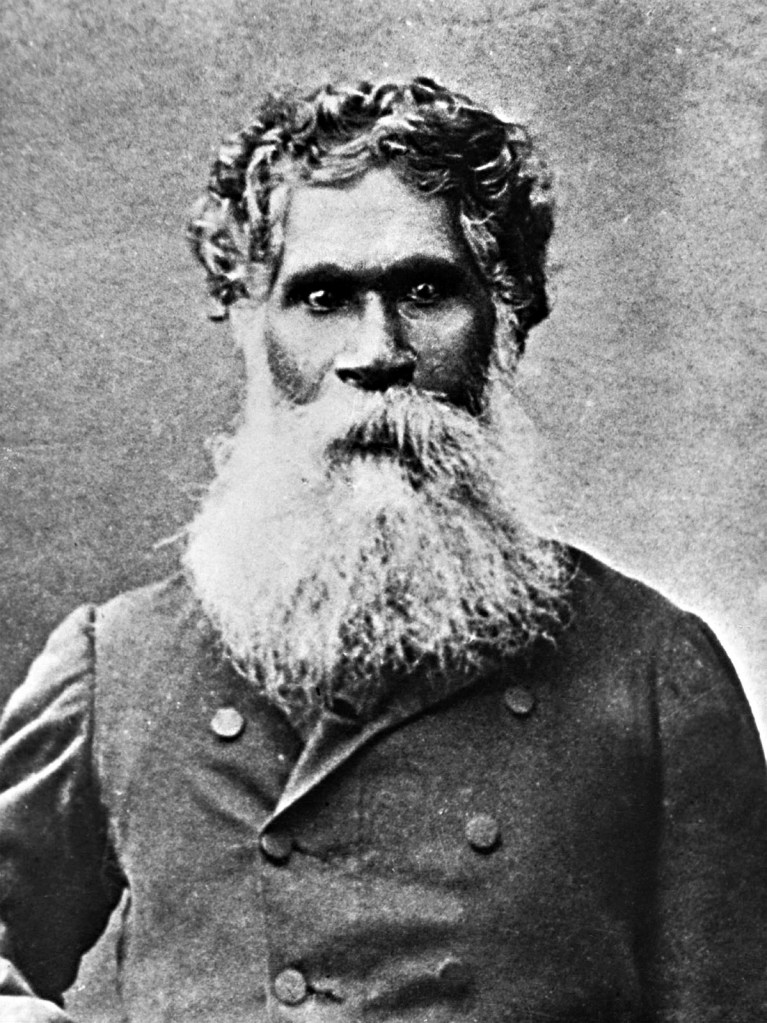

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Lap Lap (various numbers) (installation views)

2011

Mixed media

Murray Art Museum Albury, commissioned 2011

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Animal skins and woven plant fibres are preferred natural resources for making cloaks, belts, skirts and lap laps. Worn by both males and females, lap laps were created for a simple covering of the groin. Also considered a body adornment, the wearing of a lap lap has different significance between Nations. Connelly-Northey constructed these lap laps from hard and harsh materials, such as rusted industrial objects including an axe head, a cut-down rabbit trap, barbed fencing wire along with copper sheeting. Metaphorically, Connelly-Northey’s lap laps both expose and draw attention to the difficult and ‘barbed’ sexual relations thats existed between Aboriginal women and settlers, post-European arrival.

Wall text from the exhibition

Installation view of Rosalie Gascoigne’s Step through (1977 – c. 1979-1980) at the exhibition Found and Gathered at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Step through (installation view)

1977 – c. 1979-1980

Linoleum on plywood on wood

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

In 1977, Rosalie Gascoigne commenced making sculptures out of discarded linoleum, which she sourced primarily from rubbish dumps. Step through features torn pieces of floral linoleum glued to plywood which are mounted on wooden blocks, and she used a jigsaw to cut around the shapes. Although linoleum is associated with domestic interiors, for Gascoigne it was about outdoor spaces. This work references untidy vacant blocks in the city, which one might ‘step-through’ as a short cut. Gascoigne’s floor-based works are intended to be experienced from all angles, and the arrangement of the blocks at different heights creates a rhythm, drawing the eyes to wander up and across the installation.

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Smoko (installation views)

1984

Weathered wood, dried grass (possibly African lovegrass, Eragrostis curvula)

Private collection, Tasmania

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Installation views of Rosalie Gascoigne’s Pieces to walk around (1981, foreground) at the exhibition Found and Gathered at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Pieces to walk around (installation view detail)

1981

Saffron thistle sticks (Carthamus lanatus)

Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

‘This is a piece for walking around and contemplating. It is about being in the country with its shifting light and shades of grey, its casualness and it prodigality. The viewer’s response to the landscape may differ from mine, but I hope this picture will convey some sense of the countryside that produced it: and that an extra turn or two around the work will induce in the viewer the liberating feeling of being in the open country.’ ~ Rosalie Gascoigne, 1981

Piece to Walk Around is a microcosm of the landscape of the Monaro, in the southwest of New South Wales, where Rosalie Gascoigne lived from 1943. This environment provided the experiences and the materials that shaped her work, found on her journeys through it. Piece to Walk Around refers directly to the experience of moving through the Australian landscape, titled to draw attention to the changing visual effects as one circles the work and the shifting play of light on the natural material.

Comprised of a patchwork of bundles of saffron thistle stalks arranged in 20 squares lying on the floor in alternating directions, it resembles the undulating countryside, the ordering of agriculture and industry, and the mottled effects of light and shadow upon it. The work conveys a sense of the infinite expansiveness and liberation experienced in the country, as manifested in the grid’s open-ended structure to which additional bundles of thistles could theoretically be added or subtracted.

Gascoigne’s work from the early-1980s reveal a sophisticated aesthetic – an engagement with Minimalism’s orderliness and pre-occupation with the grid, and an almost Japanese mixture of formal composition and attention to nature. It was this sense of ‘order with randomness’ which Gascoigne recognised as an essential feature of the Monaro-Canberra region, and which resonates in the ‘careful-careless’ effect of this assemblage. Created only seven years after her first solo show in 1974, this work has a remarkable maturity and balance, achieved through a lifetime of looking at the landscape.

Anonymous text from the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia website Nd [Online] Cited 01/02/2022

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Takeover bid (installation view)

1981

Found window frames, thistle stems

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Takeover bid (installation view detail)

1981

Found window frames, thistle stems

Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Balance (installation view)

1984

Weathered plywood

Collection of Justin Miller, Sydney

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Balance (installation view detail)

1984

Weathered plywood

Collection of Justin Miller, Sydney

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Graven image (installation view)

1982

Weathered wood and plywood

Private collection, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne perceived wood as being distinctly different to the manufactured materials she incorporated in her art, such as tin, aluminium and iron. Wood, like the shells, dried grasses and plants she also worked with across her career, came from nature. Gascoigne gathered wood that had been weathered, including window frames and fence palings, preferring pieces that had been bleached by the sun until they were almost grey in colour. Gascoigne would use wood either as the main component of a composition, or as the backing from another work.

Installation view of Rosalie Gascoigne’s Feathered Fence (1978-1979, foreground) with Winter paddock (1984, back left) and Afternoon (1996, back right) at the exhibition ‘Found and Gathered’ at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Feathered fence (installation view details)

1978-1979

Swan (Cygnus atratus) feathers, galvanised wire mesh, metal win nuts, synthetic polymer paint on wood

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Gift of the artist, 1994

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Afternoon (installation views)

1996

Painted weathered plywood on backing boards

TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville

Gift of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

One of Rosalie Gascoigne’s late works, Afternoon, created for the exhibition In Place (Out of Time), held at the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford, comprises twenty-seven panels of weathered plywood organised in a grid-like configuration. Looking out from her vantage point at the top of Mount Stromlo across the countryside, Gascoigne was in awe of the view, the vast sky, and te sense of emptiness. The sections of lights applied white paint and areas of exposed timer of Afternoon are suggestive of passing clouds, and communicates her experiences and enduring recollections of being in the landscape.

As perhaps the most archetypal form of modernist abstraction, the grid has been employed as a formal, compositional device in countless artworks over the past century.

In ‘Grids’ (1979), Rosalind Krauss’ seminal essay on the subject, she describes this structural device as: ‘[f]lattened, geometricized, ordered, it is antinatural, antimimetic, antireal. It is what art looks like when it turns its back on nature’.(1) However, for Rosalie Gascoigne, the grid was employed as a compositional method in order to generate highly personal and experiential evocations of natural phenomena in ways which transcended the more rigid, impersonal qualities associated with its geometry.

In one of her late works entitled Afternoon (1996), Gascoigne assembled 27 individual panels of found painted timber in roughly similar sizes in a grid-like formation. At a surface level the serial repetition of components arranged and balanced according to vertical and horizontal axes corresponds to a reductive Minimalist sensibility. However, it is the heavily weathered timber with its faded white paint which infuses the work with a resonant and suggestive force. As the artist traversed the open countryside she deliberately sought out materials that she felt were ‘invested with the spirit of the place’ and capable of recalling ‘the feeling of an actual moment in the landscape’.(2) In this light, the vital materiality of the reclaimed painted timber is not only inscribed with the effects of its prolonged exposure to the elements, but it also speaks directly to Gascoigne’s deep and abiding memories of her experiences in the landscape. In Afternoon, the richly allusive quality of the individual boards is suggestive of passing clouds, evoking the ephemeral and transitory phenomena of nature in continuous metamorphosis. Contemplated as a unified pictorial whole, this humble assemblage of discarded and deteriorating matter assumes a metaphysical dimension bordering on the ineffable, one which resoundingly accords with the artist’s desire to ‘capture the “nothingness” of the countryside, those wide open spaces … the great Unsaid … the silence that often only visual beauty transcends’.(3)

Further Information

1/ Rosalind Krauss, ‘Grids’, October, Vol. 9, Summer, 1979, p. 50.

2/ Quoted in Deborah Edwards, Rosalie Gascoigne: Material as Landscape, (exh. cat.), Sydney: Art Gallery of New South Wales, 1997, p. 8.

3/ Ibid, p. 16.

Anonymous text. “Rosalie Gascoigne,” on the Culture Victoria website Nd [Online] Cited 01/02/2022

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Afternoon

1996

Painted weathered plywood on backing boards

TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville

Gift of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Winter paddock (installation view)

1984

Weathered and painted wood, painted plywood, silver gull (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae) feathers

Parliament House Art Collection, Canberra

Acquired 1985

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Winter paddock (installation view detail)

1984

Weathered and painted wood, painted plywood, silver gull (Chroicocephalus novaehollandiae) feathers

Parliament House Art Collection, Canberra

Acquired 1985

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Found and Gathered: Rosalie Gascoigne | Lorraine Connelly-Northey brings attention to the shared materiality at the heart of the practices of Rosalie Gascoigne (1917-1999) and Lorraine Connelly-Northey (b. 1962). Both artists are known for their transformative use of found and discarded objects to create works of art that challenge our understanding of the landscape, and Country.

New Zealand–born Rosalie Gascoigne is recognised for her textural works assembled from items that she had collected, including corrugated iron, feathers, wood and wire, as well as her distinctive wall-mounted pieces formed from retro-reflective road signs and soft-drink cases. Gascoigne moved to Mount Stromlo Observatory, a remote community on the outskirts of Canberra in 1943. Describing the area as being ‘all air, all light, all space, all understatement’, the surrounding region where Gascoigne regularly searched for materials greatly inspired her artistic practice. Her first exhibition was held in 1974 when she was 57 years old, and in 1982, Gascoigne was selected as the inaugural female artist to represent Australia at the Venice Biennale.

Lorraine Connelly-Northey was born and raised at Swan Hill in western Victoria, on the traditional lands of the Wamba Wamba people. Much of her work is inspired by her maternal Waradgerie (also known as Wiradjuri) heritage. Connelly-Northey gathers and uses materials often associated with European settlement and industrialisation, and repurposes them into sculptural works that reference traditional weaving techniques and Indigenous cultural objects. Through her work, Connelly-Northey explores the relationship between European and Indigenous ways of being and draws attention to the dynamic and resilient ways that Aboriginal people have been, and continue to be, custodians of Country.

Through a major display of more than 75 wall-based and sculptural works, Found and Gathered highlights each artist’s unique and significant place within Australian art, while also illuminating the sympathetic relationships between their works. Continuing the popular series of paired exhibitions hosted by NGV, this is the first exhibition in this series focused on the work of two women.

Held at The Ian Potter: NGV Australia, this exhibition includes works by both artists held in the NGV Collection as well as works from major public institutions and private collections around Australia.

Text from the NGV Australia website

Wall text from the exhibition

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Magpie bag (installation view)

2002

From the Koolimans and String Bags series

Wire mesh, magpie feathers

27.8 × 33.5 × 10.0cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2003

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Pelican bag (installation view)

2002

From the Koolimans and String Bags series

Wire, pelican feathers

31.4 × 29.7 × 10.6cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2003

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Narrbong (String bag) (installation view)

2005

Wire, wire mesh

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2005

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Narrbong (String bag) (installation view)

2005

Wire mesh, feathers

26.5 × 10.5 × 11.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2005

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Narrbong (String bag) (installation view)

2005

Wire, wire mesh, emu feathers

17.8 × 8.7 × 8.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2005

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey reproduces the form of traditional cultural objects with a range of gathered materials found on the side of the road, in illegal rubbish dumps, or decaying on farms. As she explains: ‘We Aboriginal people only take what we need when we need it. I do a lot of travelling to spot something and it can take up a lot of time. The beauty is that I always work from leftovers and if I don’t use a material, I take it back. Also, in the sculpting process, I try to not alter the material too much’.

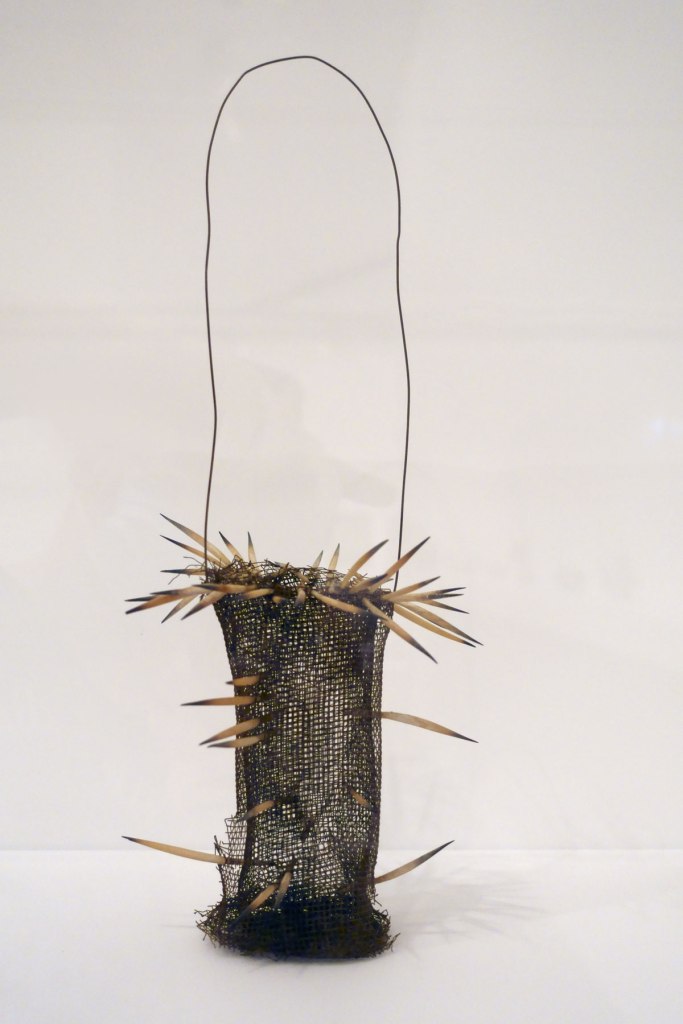

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Narrbong (String bag) (installation view)

2005

Wire mesh, echidna quills

33.0 × 15.3 × 12.0cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2005

© Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Kooliman 2 (installation view)

2002

from the Koolimans and string bags series 2002

8.5 × 29.7 × 19.2cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2003

© Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

String bag (installation view)

2002

from the Koolimans and string bags series 2002

Wire, wire mesh, feathers

23.5 × 16.4 × 8.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2003

© Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Narrbong (String bag) (installation view)

2005

Wire, wire mesh

30.7 × 14.4 × 4.7cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2005

© Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Driftwood bag (installation view)

2002

from the Koolimans and string bags series 2002

Wire, wire mesh, driftwood

15.4 × 26.5 × 7.3cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2003

© Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Narrbong (String bag) (installation view)

2005

Wire

15.9 × 22.5 × 9.4cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2005

© Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Kooliman 1

2002

From the Koolimans and string bags series 2002

16.5 × 18.0 × 14.7cm

Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and patrons of Indigenous Art, 2003

© Lorraine Connelly-Northey

Photo: NGV

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

Narrbong (Container)

2005

Iron, emu feathers

30.5 × 34 × 35.5cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Gift of Robert Cirelli, through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 2019

Photo: NGV

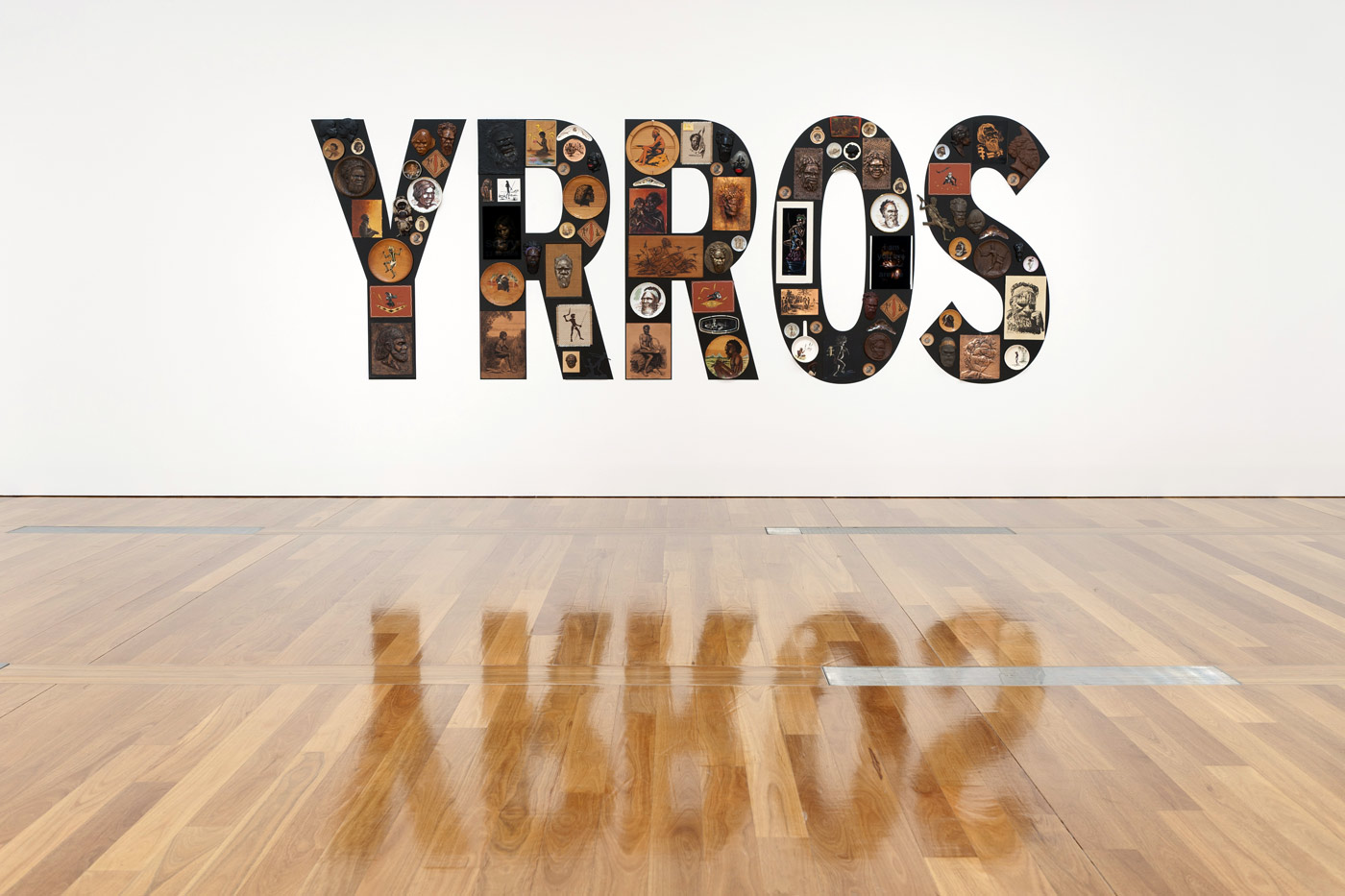

Found and Gathered

By Beckett Rozentals and Myles Russell-Cook

Found and Gathered: Rosalie Gascoigne | Lorraine Connelly-Northey brings to attention the work of two artists, both who are well known for their transformative use of found and discarded objects to create works of art. Lorraine Connelly-Northey is a contemporary artist and Waradgerie (Wiradjuri) woman living on Wamba Wamba Country. Rosalie Gascoigne was born in Aotearoa (New Zealand), and moved to Mount Stromlo Observatory, a remote community in the Australia Capital Territory on the lands of Ngunawal people, in 1943. Both are celebrated as two of Australia’s pioneering contemporary artists.

Gascoigne passed away in 1999 not long after Connelly-Northey first began exhibiting. They never met, and it was not until many years after first showing as an artist that Connelly-Northey became aware of Gascoigne and her work. Despite never meeting, some enduring parallels between their work are evidence of their shared love for the natural sophistication of found objects. Found and Gathered: Rosalie Gascoigne | Lorraine Connelly-Northey is the first major exhibition to unite these artists, providing a conversation between artists and across time. Together these inspiring sculptors challenge our understanding of found materials, of seeing the landscape, and of being on Country.

Rosalie Gascoigne is recognised for textural works assembled from collected items, including corrugated iron, wire, feathers and wood, as well as her distinctive wall-mounted pieces formed from split soft-drink cases and brightly coloured yellow and red road signs. Producing work primarily about the landscape, Gascoigne’s art practice stemmed from her appreciation of humble found objects and weathered materials. Gascoigne sourced objects from the Southern Tablelands and the Monaro district, unique natural environments that lie close to Canberra, describing the regions as ‘all air, all light, all space, all understatement’,1 as well as building sites, refuse and recycling centres.

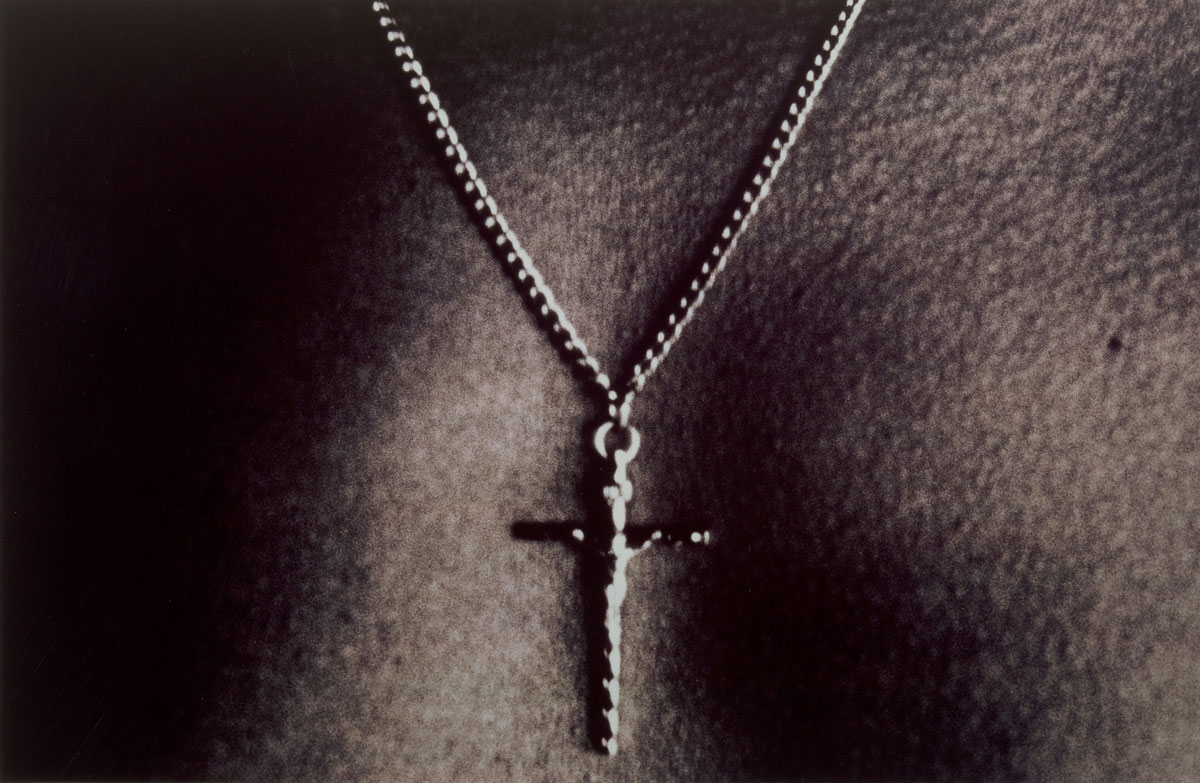

Born in 1962 and raised at Swan Hill in western Victoria, on the traditional lands of the Wamba Wamba people, today Lorraine Connelly-Northey is known for gathering and utilising industrial remnants associated with European settlement. Her practice is founded in the union of her father’s Irish heritage with her mother’s Waradgerie2 heritage. Since 1990, Connelly-Northey’s strong desire to undertake traditional Aboriginal weaving has resulted in a rediscovery of her childhood bush environments of the Mallee and along the Murray River, to learn more about Aboriginal lifestyle prior to European settlement.

Gascoigne commenced classes in the Japanese art of ikebana in 1962, studying under Tokyo-trained Norman Sparnon, who taught the modern Sogetsu school. Ikebana was to significantly inform the basis of her sculptural works. Looking towards line and form over colour, Gascoigne commenced making assemblages in 1964, her first works created from discarded rural machinery. In a similar way, the materials that Connelly-Northey works with are both natural and inorganic, combining items such as discarded wire, metal and scraps of old housing, with wood, shells, feathers and other naturally occurring media. In bringing together disparate materials, Connelly-Northey also uses her work to push audiences to consider the relationships between First Peoples and settler societies, and critiques the ongoing dispossession that is experienced by Aboriginal people throughout Australia.

Gascoigne’s first solo exhibition was held at Macquarie Galleries, Canberra, in 1974 when she was fifty-seven years old. Gascoigne quickly rose to prominence as one of Australia’s most admired artists, and four years later, she was the focus of Survey 2: Rosalie Gascoigne held at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourrne. In 1982, Gascoigne was the first female artist to represent Australia at the Venice Biennale. Following her distinguished career, a retrospective of Gascoigne’s work opened at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia in 2008.3

Exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1982 was Gascoigne’s first iron work, Pink window, 1975, an assemblage comprising a window frame and painted corrugated galvanised iron. Gascoigne stated of the work that

The pink and the shape and everything was actually as I found it, and I didn’t do a thing to it. It was only after quite some months I realised it could sit on that window frame. At the time I was on about the emptiness of the Australian landscape, and I kept thinking of a woman stuck out there on the plains standing at her window. She looks out, what does she see? Nothing. It spoke of loneliness or something … and it got happier as time went on. The pink carries it … the pink is very beautiful.4

Across her career, Gascoigne gathered wood, with a preference for pieces that had been weathered, such as fence palings and apiary boxes, as well as a dozen abandoned pink primed window frames, including the one featured in Pink window.

For Connelly-Northey, gathering her materials and ‘cleaning up’ the landscape is one in the same. She describes the act of ‘gathering’, as an act of ‘taking back Country’. Caring for lands and waterways and the importance of preserving culture are two things that were instilled in her from a young age, by both her mother and father, who encouraged her to reuse discarded materials, and taught her handiwork and craft.

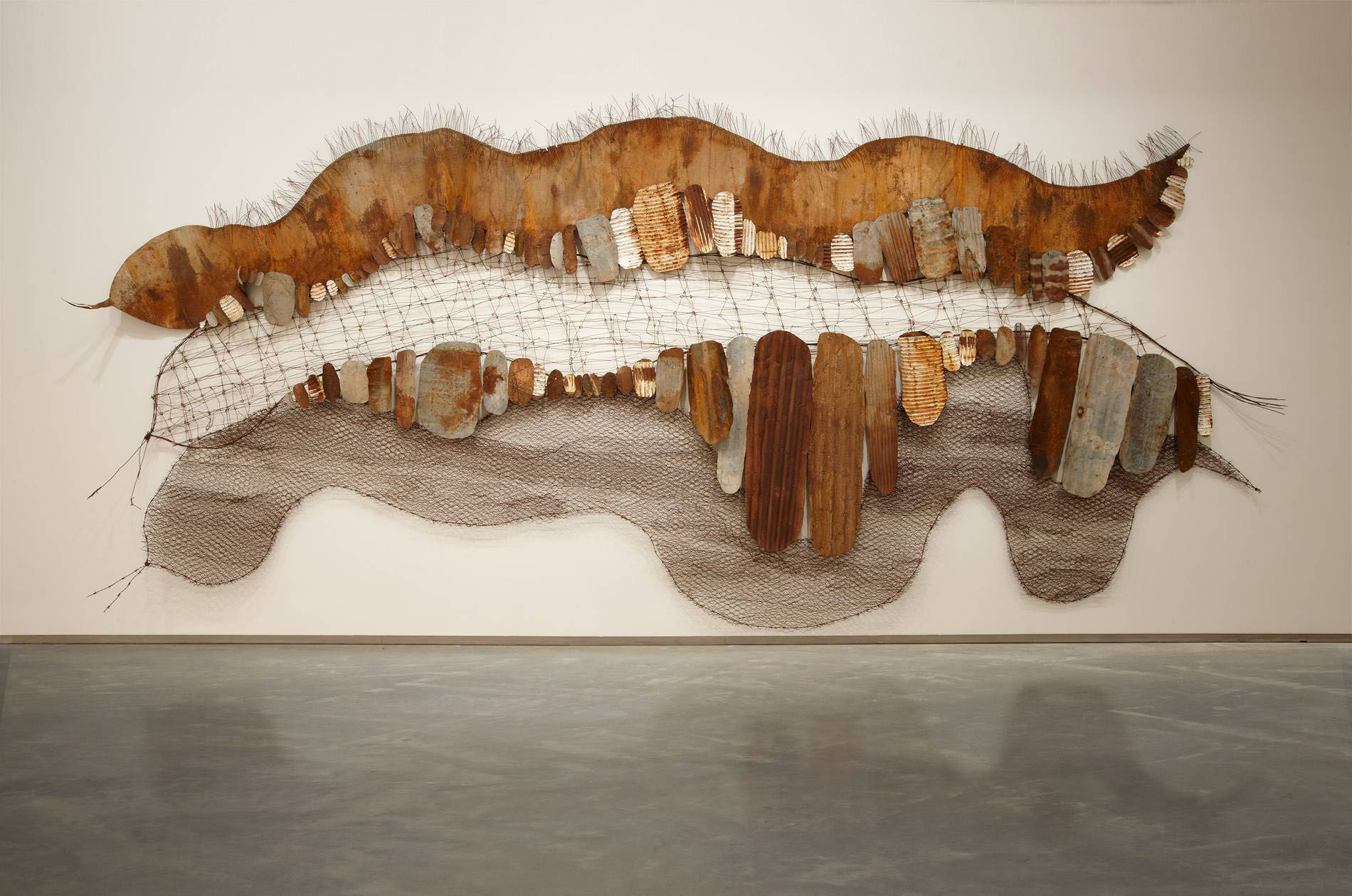

Many of Connelly-Northey’s sculptures take the form of classical Aboriginal cultural objects, such as narrbong-gallang (string bags), kooliman-gallang (coolamons), possum-skin cloaks and lap laps. These objects can be rendered simply, such as her rectangular sheets of metal with bent wire handles and her drawings with cable wire, or as elaborately constructed pictorial installations, which combine a variety of mixed media. Connelly-Northey uses the title A Possum Skin Cloak as a way of introducing the cultural stories that appear within her more dioramic installations. Presented for the first time in this exhibition, Connelly-Northey unites four of her most ambitious possum skin cloak installations: A Possum Skin Cloak: Three rivers country, 2010 (Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney); A Possum Skin cloak: Blackfella road, 2011-2013 (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne); A Possum Skin Cloak: On Country, 2017 (Murray Art Museum Albury); and her most recent work, A Possum Skin Cloak: Hunter’s Duck Net, 2021 (courtesy of the artist).

A Possum Skin Cloak: Hunter’s Duck Net depicts a traditional duck net cut from oxidised, corrugated iron, that hangs, framed between two majestic river red gums, one a scarred ‘canoe’ tree. Traditionally, when using duck nets, Aboriginal hunters would throw a boomerang, no doubt a returning one, overhead like a predatory hawk to the startle the ducks, forcing them to fly low and into the net strung across the tributary of the river. The ducks in Connelly-Northey’s work appear animated, some still on the water’s surface, others in mid-flight before being either trapped or escaping the net. The encircling boomerang can be seen at the top of this dioramic scene giving audiences a sense of the action at the moment just before the ducks become ensnared.

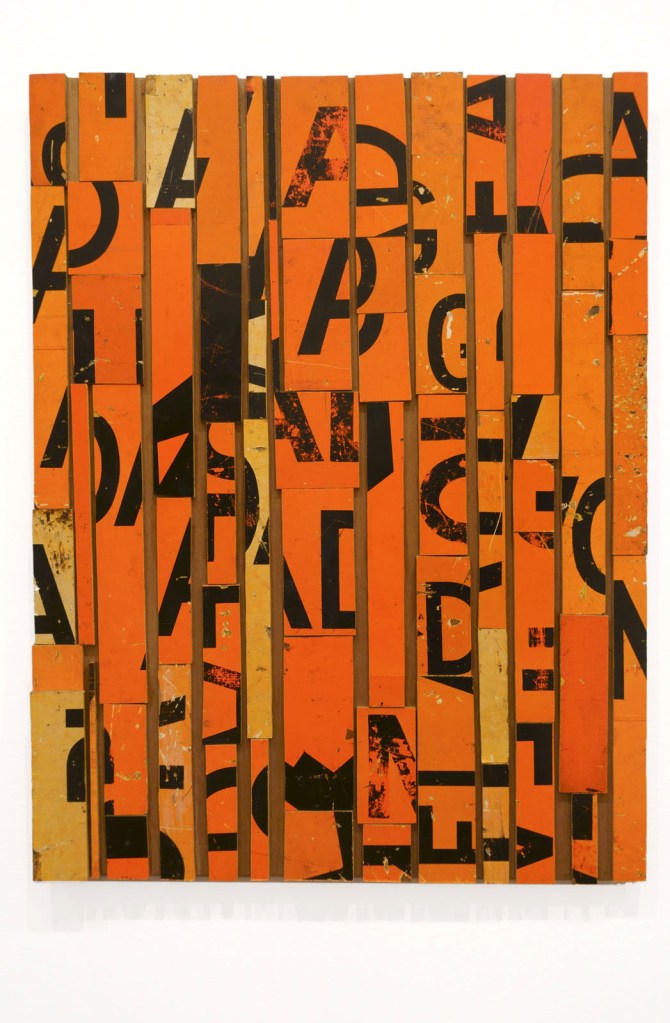

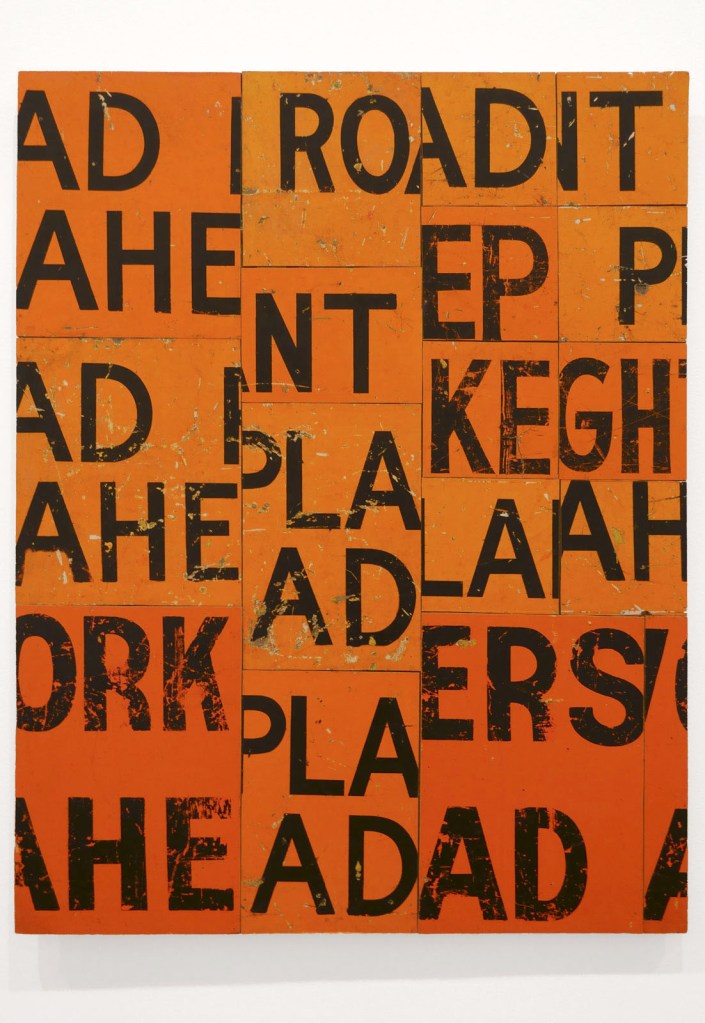

Gascoigne is perhaps most well known for her unique assemblages constructed from cut up and rearranged retro-reflective road signs that flash and flicker in the light. The first signs she found were discovered face down in the mud at a roadside dump and, by chance, had already been cut up into squares. Gascoigne, taken by the way the material responded to the light, began salvaging signs no longer in use, collecting examples abandoned on the side of the road and also at road maintenance depots.

Gascoigne’s use of the boldness of the retro-reflective road signs to reveal her ongoing interest in the expressive possibilities of the grid is exemplified in Flash art, 1987. In this work, Gascoigne has explored all aspects of the featured lettering and negative space, creating whole words, as well as including sections and fragments of text. The title references the reflective quality of the material, with Gascoigne stating that: ‘It was the most blasting of the retro-reflectives I ever did, because it was eight feet by eight feet, it had road tar on it, and when it lit up, boy, it was every bushfire’.5 The gestural smears of black tar across the bright yellow surface additionally links the work back to the roads and highways where the signs were once positioned in the landscape.

The customary shapes and forms that appear and reappear throughout Connelly-Northey’s work most often reference the cultural objects of her ancestors, and the stories embedded within Country. Connelly-Northey has dedicated a great deal of her life to researching and exploring how these cultural objects, as well as knowledge associated with Aboriginal custodianship of Country can be reimagined using materials associated with colonisation.

One of Connelly-Northey’s most ambitious installations, A Possum Skin Cloak: On Country, overflows across two adjoining walls. This major diorama features a series of blue, white and brown koolimans representing the twin cities Albury and Wodonga. Albury was originally known by the Waradgerie as Bungambrawatha, meaning Homeland. Wodonga retained its original name, which refers to a type of plant called cumbungi, a bush potato that is also commonly known as bulrush. Within the installation are two canoes placed on the body of the barbed-wire snake that represents the Murray River.

The large possum skin cloak that adjoins to the central installation represents the land of the grass seed people, the Waradgerie. Connelly-Northey has rendered her cloak in rusted iron and sections of pressed tin that were salvaged from Albury’s former town hall ceiling during the renovations of the Murray Art Museum Albury. It is distorted and undulates, creating a sense of folded fabric.

Both Connelly-Northey and Gascoigne’s work is defined by, and yet transcends, its sense of materiality. Gascoigne perceived the wood, shells, feathers and dried grasses that she collected as being markedly different to the industrial objects incorporated in her art, such as tin, aluminium and iron. Instead, these materials came from nature itself. Connelly-Northey views the act of gathering as one of the central inspirations behind her practice. Rather than drawing attention to the differences between collected materials, Connelly-Northey uses traditional weaving, not assemblage, as a way of bringing together that which is disparate.

Gascoigne and Connelly-Northey each dissociate objects from their original function, while simultaneously reflecting their individual experiences of being immersed in the bush environment. Despite their careers having been separated by time, and coming from vastly different backgrounds, in both artists we see a singular vision that is immediately recognisable, and unmistakably them. And yet there is a sympathetic connection between their practices that is undeniable.

Beckett Rozentals and Myles Russell-Cook

Notes

1/ Rosalie Gascoigne, interview with Peter Ross, ABC, 1990.

2/ ‘Waradgerie’, also known as ‘Wiradjuri’, is the artist’s preferred spelling.

3/ For further reading on the artist’s career and exhibition history, see Martin Gascoigne, Rosalie Gascoigne: Catalogue Raisonné, ANU Press, Canberra, 2019.

4/ Rosalie Gascoigne, interview with Ian North, Canberra, 9 Feb. 1982. Transcript held in National Gallery of Australia Research Library, Canberra, and Rosalie Gascoigne papers, box 21, National Library of Australia, Canberra.

5/ Rosalie Gascoigne quoted in Viki MacDonald, Rosalie Gascoigne, Regaro Pty Ltd, Paddington, Sydney, 1998, p. 76.

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Country air (installation view)

1977

Painted and corrugated galvanised iron, weathered wood, plywood

National Gallery of Australia

Purchased 1979

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne began incorporating both sheet and corrugated iron in her work between 1973 and 1974. Gascoigne viewed galvanised iron as a very ‘Australian’ material, and she continued using iron until 1998, experimenting with different weights and colours of the pieces she collected. Country air comprises four heavy, weathered and dented corrugated sheets, which Gascoigne found at the Canberra Brickworks in 1976, and are presented in the state that she found them. Encased in the simple timber frames, the ripples and bent pieces of iron have the illusion of curtains gently blowing in a breeze.

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Country air (installation view detail)

1977

Painted and corrugated galvanised iron, weathered wood, plywood

National Gallery of Australia

Purchased 1979

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosalie Gascoigne’s Crop 2 (1982, foreground) and Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s A Possum Skin cloak: Blackfella road (2011-2013, background) at the exhibition Found and Gathered at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Crop 2 (installation views)

1982

Salsify (Tragopogon porrifolius), galvanised wire, corrugated iron

National Gallery of Victoria

Gift of Ben Gascoigne AO

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Crop 2 comprises a piece of chicken wire that seems to float over a sheet of galvanised iron. The two are connected by hundreds of dried salsify heads (Tragopogon porrifolius – part of the daisy family), which are stripped of their leaves and threaded through the holes in the wire. The resulting effect is a poetic evocation of cultivated land, and of order imposed on the natural environment. Evident in Crop 2 is the influence of the artist’s training in Sogetsu ikebana, as it is based on a knowing combination of intuition and discipline, and a concentrated search for an essential form.

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

A Possum Skin cloak: Blackfella road (installation view)

2011-2013

Rusted iron and tin, fencing and barbed wire, wire

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2014

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

A Possum Skin cloak: Blackfella road (installation view)

2011-2013

Rusted iron and tin, fencing and barbed wire, wire

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2014

Photo: NGV

Wall text from the exhibition

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

A Possum Skin cloak: Blackfella road (installation view details)

2011-2013

Rusted iron and tin, fencing and barbed wire, wire

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2014

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

A Possum Skin cloak (installation view)

2005-2006

From the Hunter-gatherer series

Rusted corrugated iron

119.5 × 131.5 × 5.0cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2006

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

A Possum Skin cloak (installation view)

2005-2006

From the Hunter-gatherer series

Steel, Chinese chicken feathers

148.0 × 132.0 × 10.0cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2006

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

A Possum Skin cloak (installation view detail)

2005-2006

From the Hunter-gatherer series

Steel, Chinese chicken feathers

148.0 × 132.0 × 10.0cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by Supporters and Patrons of Indigenous Art, 2006

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Rosalie Gascoigne’s Milky way (1982, far left) and her Lantern (1990, third right) and Vintage (1990, second right) at the exhibition Found and Gathered at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Milky way (installation view)

1995

Painted wood

TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville

Gift of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne moved to Mount Stromlo Observatory in 1943 to marry astronomer Ben Gascoigne, who she had previously met while studying at university in Auckland. The first of their three children was born later that year. It was also in 1943 that Gascoigne started exploring the region on foot, bringing home objects she discovered on her journeys. Milky way is one of just two works Gascoigne produced directly related to an astrological theme. Following his wife’s passing, Ben Gascoigne stated that although Gascoigne had many chances, at no time did she look through te telescopes at the Observatory during they years they lived there.

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Lantern (installation view)

1990

Sawn plywood retro-reflective road signs on plywood backing

TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville

Gift of Eva Besen AO and Marc Besen AC

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Vintage (installation view)

1990

Sawn plywood reflective road signs on composition board

Private collection, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of the exhibition Found and Gathered at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia showing at right, Rosalie Gascoigne’s Yellow beach (1984)

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

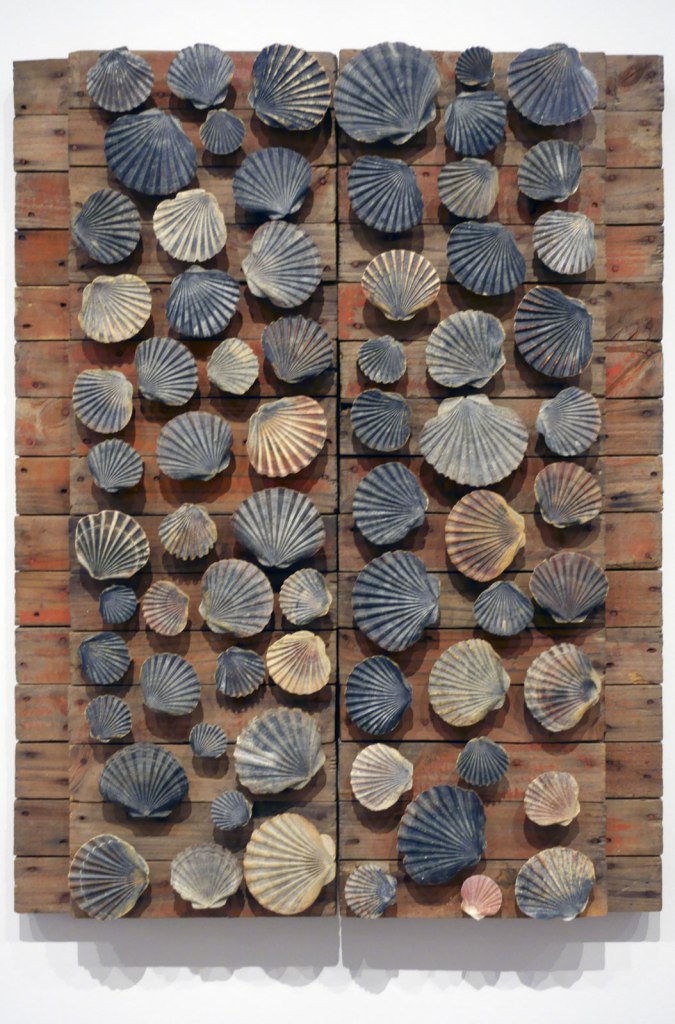

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

(Yellow beach) (installation view)

1984

Scallop shells, painted wood, plywood

Private collection, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Red beach (installation view)

1984

Wood, nails, shells, paint

Private collection, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

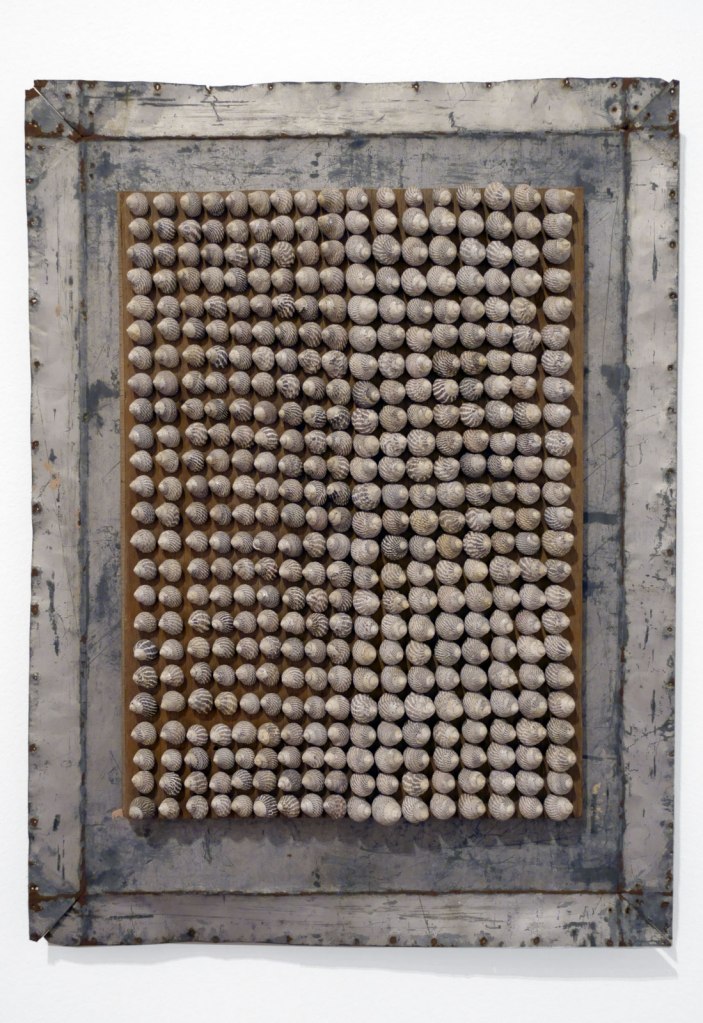

Rosalie Gascoigne was an avid shell collector, often focusing on gathering just one type of shell at a time, and storing them in boxes, jars and bowls. Discerning in her selection, she brought home only shells she deemed to be of good colour and with no chips. The Tasmanian scallop shells used in Red beach, (Yellow beach) and (Twenty-five scallop shells) were collected by Gascoigne’s son, Toss, who was living in Hobart at the time. He gathered them from Seven Mile beach, just near Hobart Airport, which the family used to visit.

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Red beach (installation view)

1984

Wood, nails, shells, paint

Private collection, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Twenty-five scallop shells (installation view)

c. 1984-1986

Scallop shells, wood

Private collection, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Twenty-five scallop shells (installation view detail)

c. 1984-1986

Scallop shells, wood

Private collection, Canberra

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Turn of the tide (installation view)

1983

Painted wood, galvanised iron, shells

Private collection, Sydney

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Turn of the tide (installation view detail)

1983

Painted wood, galvanised iron, shells

Private collection, Sydney

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

Installation view of Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s On Country (2017) at the exhibition Found and Gathered at The Ian Potter Centre NGV Australia

Photo: Marcus Bunyan

The installation On Country overflows onto the adjoining wall with this possum skin cloak. This component on On Country represents the land of the grass seed people, the Waradgerie. The object has been rendered in rusted iron and sections of pressed tin, and the cloak is fringed with white and brown koolimans of varying scales, which were salvaged from Albury’s former town hall ceiling during renovations of the Murray Art Museum Albury. The rusted sheet is distorted and undulates over the entire object creating a sense of folded fabric.

Installation view of Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s On Country 2017, on display at MAMA, Albury

© the artist

Wall text from the exhibition

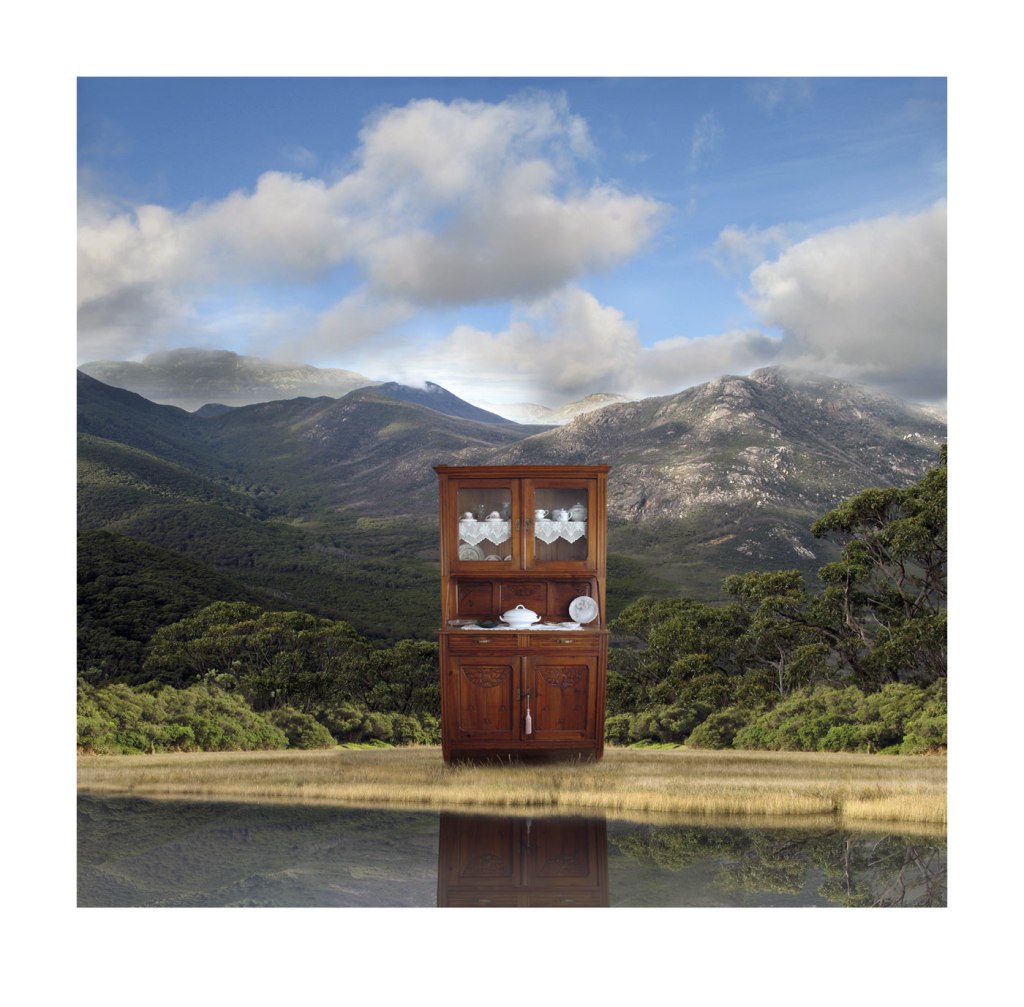

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Inland sea

1986

Weathered painted corrugated iron, wire

(a-ff) 39.1 x 325.0 x 355.5cm (variable) (installation)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1993

© Rosalie Gascoigne Estate/Licensed by Copyright Agency, Australia

In Inland sea, 1986 (above), sixteen large sheets of corrugated tin hover above the floor in a loose grid arrangement. The grid format unifies the separate parts of the composition, and also enhances the expressive power of different visual elements through repetition. The shapes and lines repeated across the buckling sheets of tin create a powerful sense of the gentle movement of wind or water.

The strong visual rhythms and movement evident in Gascoigne’s compositions are often achieved through the repetition of different visual elements. Step through, 1980 (above), is made from fifteen separate parts, each made from a torn piece of brightly coloured, floral patterned linoleum mounted on a block of wood. The blocks sit at different angles creating different levels within the installation. The spaces between the different parts create a meandering path for the viewer to explore, highlighting the importance of movement through and across space in Gascoigne’s work.

“I was thinking about the unkempt empty blocks in built up city areas … usually covered in rank grasses and flowering weeds … rubble, old tins and bottles. One steps through them gingerly and, with possible snakes in mind, lifts one’s knees high.” ~ Vici MacDonald, Rosalie Gascoigne, Regaro Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1998, p. 48

Text from the NGV Rosalie Gascoigne Education Kit

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Honey flow

1985

Painted and stencilled wood, nails on plywood backing

Collection of Justin Miller, Sydney

Some of the most eye-catching and striking board pieces by Rosalie Gascoigne are her compositions created out of distinctive yellow Schweppes soft-drink boxes. In 1985m Gascoigne created her first all-yellow-soft-drink box work, Honey flow, which was the same year she made her first all-yellow retro-reflective work. With both these materials, Gascoigne explored all aspects of the featured lettering and negative space, including whole words, sections of texts and letters, and isolated shapes. She also experimented with different degrees of weathering and shading of her materials.

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

All summer long

1996

Sawn painted and stencilled wood from soft-drink boxes

Bendigo Art Gallery, Bendigo

One of Rosalie Gascoigne’s largest wall-base pieces, All summer long was included in an exhibition of her all-yellow works held at the Adelaide Festival in 1996. The title references the long hot summer days experienced in Adelaide and its surrounds – the sunburnt landscape turning yellow. The slivers of black text once read ‘Schweppes screw top 32 fl. oz’, and the areas of split and broken text rise and fall against the expanses of the muted golden tones, drawing the eye steadily across the composition.

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Flash art

1987

Tar on reflective synthetic polymer film on wood

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds donated by the Loti and Victor Smorgon Fund, 2010

Created from cut-up road signs that have been rearranged and organised in a grid configuration, the scratched panels and fragments of disconnected text form a striking abstract field of flickering letters against a bright yellow background. This work exemplifies Rosalie Gascoigne’s poetic use of found objects, particularly those containing text. The open structure and repetitive patterns evoke a sense of expansiveness and space, while the weather-beaten surface with gestural smears of tar connects it to a particular idea of place.

Wall text from the exhibition

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Suddenly the lake

1995

FSC-coated plywood formboard, painted galvanised iron sheet, synthetic polymer paint on composition board

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Given by the artist in memory of Michael Lloyd, 1996

Suddenly the lake is based on the view of Lake George at Gearys Gap, New South Wales, seen while driving along the Federal Highway out of Canberra. The parallel hills also reference the work of New Zealand artist, Colin McCahon, who Gascoigne greatly admired. Gascoigne referred to the curved piece of formboard used in the work as her ‘Ellsworth Kelly curve’ as it reminded Gascoigne of American artist Kelly’s Orange curve, 1964-1965 (below), which she had viewed at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.

Ellsworth Kelly (American, 1923-2015)

Orange curve

1964-1965

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Clouds III

1992

Weathered painted composition board on plywood

(a-d) 75.4 × 362.2cm (installation)

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased 1993

Evocative of clouds shifting and transforming shape across the horizon, the hand-torn masonite shapes incorporated into Clouds III speak to the transience of natural phenomena. The metaphysical quality Rosalie Gascoigne imbued in everyday materials that had been discarded enabled her to, as she articulated it, ‘capture the “nothingness” of the countryside, those wide-open spaces … the great Unsaid … the silence that often only visual beauty transcends’. Clouds III was originally displayed as part of an installation of three Cloud works at Roslyn Oxley9, Sydney, in 1992.

Rosalie Gascoigne (Australian born New Zealand, 1917-1999)

Pink window

1975

Window frame, pink undercoat, corrugated iron

116.0 x 104.0 x 10.0cm

Private Collection, Canberra

© Rosalie Gascoigne / Copyright Agency, Australia

Lorraine Connelly-Northey (Australian / Waradgerie, b. 1962)

A Possum Skin Cloak: Three rivers country

2010

Burnt finely corrugated tin, rusted wire, fenced wire, rabbit proof fencing wire, corrugated iron, tin, wire

Museum of Contemporary Art, purchased with funds provided by the Coe and Mordant families, 2010

Image courtesy the artist and Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

© the artist

Photo: Jenni Carter

“Three rivers country pays homage to my mother’s knowledge of water on country. The work is my interpretation of an opossum skin cloak with incisions depicting rivers and koolimans. The work represents the land of the ‘Waradgerie Winnowers’, my mother’s tribal boundary, Waradgerie Country.”

Lorraine Connelly-Northey, 2010

In Lorraine Connelly-Northey’s A Possum Skin Cloak: Three rivers country, she challenges conventioanl historical narratives, employing the objects of Western industry to map Waradgerie Country. Waradgerie Country, in central New South Wales, is often referred to as ‘Three rivers country’, because the Wambool (the Macquarie), the Kalari (the Lachlan) and the Murrumbidjeri (Murrumbidgee) rivers course through it. As the artist states: ‘Three rivers country pays homage to my mother’s tribal boundary, Waradgerie Country, along with the peoples known as the grass seed people who created koolimans to winnow their seed for seed cake making’.

Waradgerie (Wiradjuri) country in central New South Wales is vast, with hills in the east, river floodplains and grasslands in the interior and mallee to the west. It is known as Three Rivers Country, as the Murrumbidgee, Kalari (Lachlan) and Wambool (Macquarie) rivers course through it, teeming with life. But as the colonial frontier spread west from Bathurst in the early 1800s, the Three Rivers Country was surveyed and cleared, dissected and demarcated, and kilometres of fencing spread through Waradgerie land like cracks through ice.

In her epic installation Three rivers country Lorraine Connelly-Northey wrestles with this history, employing the objects of western industry to map her country. The materials she uses marry the two foundations of her practice: the heritage of her Waradgerie mother and the heritage of her Irish father. While her father encouraged her use of discarded materials, it was as a young child with her mother that she honed her fine handiwork skills through crocheting and sewing. As Connelly-Northey explains: ‘I set out to ensure that however my art developed it would represent my parents equally.’1

In this work the snaking rivers dominate, shifting from rusted rippled iron and the delicate open weave of agricultural fencing to the familiar lacework of rabbit-proof wire. Tying these forms together are coolamons: oval-shaped bowls that form both the riverbanks and the great, cultivated plains of the interior. The work, says Connelly-Northey, ‘pays homage to my mother’s knowledge of water on country … [and represents] the land of the “Waradgerie Winnowers”.’ But it also speaks to her mother’s life experience, ‘born and raised on the banks of freshwater rivers’ in shanties patch worked together with discarded materials like those Connelly-Northey uses in her works of art.

Notes

1/ Lorraine Connelly-Northey quoted in Julian Bowron, Lorraine Connelly-Northey: Waradgerie weaver, exh. cat., Swan Hill Regional Art Gallery, Victoria, unpaginated.

2/ Lorraine Connelly-Northey, artist’s statement, in Carly Lane and Franchesca Cubillo (eds.,), unDisclosed: 2nd National Indigenous Art Triennial, exh. cat., National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2012, p. 39.

Anonymous text. “Lorraine Connelly-Northey: Three rivers country, 2010,” on the Museum of Contemporary Art website [Online] Cited 28/12/2021. No longer available online

Aboriginal Nations / Languages in NSW and ACT – Mount Stromlo is in the ACT (Canberra on the map)

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

Federation Square

Corner of Russell and

Flinders Streets, Melbourne

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Unknown photographer. '[A group of Aboriginal men at Coranderrk Station, Healesville]' Nd Unknown photographer. '[A group of Aboriginal men at Coranderrk Station, Healesville]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/sixteen-aboriginal-men.jpg)

![Talma & Co. (1893-1932) 119 Swanston St. Melbourne 'Barak, Chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe. [Barak drawing a corroboree]' c. 1895-1898 Talma & Co. (1893-1932) 119 Swanston St. Melbourne 'Barak, Chief of the Yarra Yarra Tribe. [Barak drawing a corroboree]' c. 1895-1898](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/william-barak-a.jpg?w=655)

![Rex Hazlewood (Australian, 1886-1968) '[Men drinking billy tea]' 1911-1927 Rex Hazlewood (Australian, 1886-1968) '[Men drinking billy tea]' 1911-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/hazelwood-billy-tea.jpg)

![James Fox Barnard (Australian, 1874-1945) '[Tea on the verandah]' c. 1900 James Fox Barnard (Australian, 1874-1945) '[Tea on the verandah]' c. 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/barnard-tea-verandah.jpg?w=754)

You must be logged in to post a comment.