Exhibition dates: 26th May – 29th October 2022

Curator: Fiona Oliver

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Businesses of Harding and Richardson, Ridgeway Street, Wanganui

c. 1870s

Wet collodion glass negative

6.5 x 8.5 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Buildings on Ridgeway Street, Wanganui, circa 1870s, including that of W J Harding, photographer, and Mrs Richardson, dressmaker.

William Harding’s studio, Ridgeway St, Whanganui, c. 1870s. He used this studio from 1860 until 1889, when he left for Sydney. His collection of 6,500 glass-plate negatives were nearly dumped by the studio’s new owner but were rescued by a relative of Harding’s and the Whanganui Museum. They were bought by the Turnbull Library in 1948.

Reclaiming the light

A fascinating posting on the portrait photographs of New Zealand photographer William Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899), which “provide a detailed picture of Whanganui society from the 1850s to the 1880s, and are a rich source of information relating to Māori and Pākehā individuals and their relationships at a formative time in this country’s history… He’d come to New Zealand from England as a coachbuilder in 1855, along with his wife Annie. He tried his hand at cabinet-making, and in 1860 set up a photographic studio in Ridgway St, Whanganui.”1

In the main the photographs are the usual Victorian colonial fare of formal studio portraits of white settlers (Master Percival Thomas Scott), the standing or sitting subjects posed with props on linoleum floors against rolls of plain paper or painted backgrounds staring straight into the camera lens or obliquely off into the distance. Harding’s portraits never flatter to deceive: “Harding’s sitters are also largely unsmiling. But their faces are alight, staring down the camera, eyes aflame. Sometimes they look peevish, bored or exhausted. There seems to be little inclination towards idealisation. Harding refused to retouch his photographs as other commercial photographers did. Faces are weathered and freckled; clothing is often ragged, mended or borrowed, illustrating the hardships of colonial life… The women, men, children, families and other groups who sat for him are shown with sensitivity and honesty.”2

Occasionally the framing is more interesting, as in the negative space which surrounds the profile portrait of [Miss] Scott (Between 1870-1889, below), the placement of the figure within the pictorial frame in Mrs Gillen (1870s, below), or the closeness to the subject so that the strong face fills the frame in Unidentified Maori man, with moko, Whanganui district (1860s, below). Group photographs are also taken outdoors against hanging rug or fabric backdrops which are pinned to the exterior of weatherboard houses, probably as Harding travelled around the district or was commissioned to take the family portrait. As with other colonial portrait photographs from around the world, treasured possessions such as photographs, sewing machines, clocks, birds, bibles, and books are placed on covered tables to signify their importance in the colonists lives.

What is undeniable is the wonderful, casual yet almost crystalline presence that Harding’s sitters possess… no doubt due to his perception as a human being and a photographer, to his association with the community in which he lived, and to the clarity of the glass plate negatives that he produced. In this regard you only have to look at the portrait of Mr Plampin (17 August 1883, below) in all his Dickensian glory to understand what a great photographer William Harding was… in his ability to convey with perspicacity the personality of the sitter, that bright spark that was their life.

Through his portrait textures and tonalities there is a sense of the people who populate that place, but more than that, there is a sense of our own fragility and mortality. A feeling of anOther existence for our life if we had been born into such worlds. It is a little disappointing then that none of Harding’s many photographs of pairs of men are present in the exhibition, such as the photograph with the dog on the front of the book Mates and Lovers: A History of Gay New Zealand by Chris Brickell (2009), which is a Harding image (see photograph below).3 Hidden histories indeed!

As interesting, and just as problematic, are the portraits by a white photographer of the Māori and their artefacts, indigenous Polynesian people of mainland New Zealand (Aotearoa). First of all can I say that I am not an expert in the field of colonial photography of First Nations peoples including the photographs of the Māori of New Zealand. This is a complex and contested terrain requiring specialised knowledge of ancient histories, cultures and memories, where the reclaiming and becoming is being undertaken mostly by scholars and First Nations peoples and artists.

Having said that, what I can observe is that ALL photographic histories of colonised peoples – whether it be for example photographs of Indigenous Australians, indigenous people of the United States or African colonial photographs – are contested terrain which needs to be reclaimed by ancestors: from the posing of “conquered” people; to the gaze of a white male photographer; to the “impartial” gaze of the machine; to the possession of the body and artefacts of the possessed through the physicality of the photograph; to the scripting of a particular un/reality, a story photographers wanted to tell; to the scientific, anthropological measuring of physiognomies (anthropologists were interested in documenting hair styles and scarification marks, as well as tattoos, moko, and facial characteristics); to the representation of many cultural items and ancestors that have been stolen; to the photographs ability to “show us today some things that we may no longer have access to and give us a window into eyes of real human beings who were in the process of losing the lives they had known for centuries.”4 To name just a few terrains and identities that need to be reclaimed.

Very briefly, in the history of New Zealand (and the “new” in the title speaks for itself, despite the fact the Polynesian people of Aotearoa had been on the islands for centuries before the British), in 1841 “representatives of the United Kingdom and Māori chiefs signed the Treaty of Waitangi, which in its English version declared British sovereignty over the islands. In 1841, New Zealand became a colony within the British Empire. Subsequently, a series of conflicts between the colonial government and Māori tribes resulted in the alienation and confiscation of large amounts of Māori land.”5

Although there was only “estimated a scant 1100 Europeans in the North Island in 1839, with 200 of them missionaries, and a total of about 500-600 Europeans in the Bay of Islands” compared with an estimated population of 30-40,000 Māori by 1870, with the arrival of new immigrants and the issue of land-ownership, Justice Minister Henry Sewell (in office 1870-1871) described the aims of the Native Land Court as “to bring the great bulk of the lands in the Northern Island […] within the reach of colonisation” and “the detribalisation of the Māori – to destroy, if it were possible, the principle of communism upon which their social system is based and which stands as a barrier in the way of all attempts to amalgamate the Māori race into our social and political system.” By the end of the 19th century these goals were largely met – to the detriment of Māori culture.”6

There are many complexities around colonial photography – on both sides of the lens – and the decolonisation of collections and museums / galleries in general is a difficult area. “The ‘archival turn’ of the 1990s has brought increased scrutiny to the practices of collecting, collating, and classifying photographs and artefacts – procedures that are now sites of contested histories.”7 Despite the repurposing of the colonial archive and the decolonisation of historical images, we must accept that the Māori people photographed in Harding’s portraits were subjected to the colonial gaze: “Originally photographed and collected to document a so-called primitive race or culture, or as part of tourism and government programmes of protection and assimilation, the colonial archives remained inaccessible to First Nations peoples until recent decades.”8 We must acknowledge the usual myths (for example, that authentic Māori culture was about to be or had been lost through Māori degeneration – the myth of the dying race) and stereotypes presented by colonials who “discovered, created, propagated and romanticised the Maori world at the turn of the century summed up in a popular nickname describing New Zealand; Maoriland [in which] the culture of Maoriland was a colonists creation…”9 but we must also acknowledge (as with Indigenous Australians10) the part Māori played in manipulating colonial myth-making for their own purposes, that “Māori were not merely passive victims: they too had a stake in this process of romanticisation…”11

But as Indigenous Australian artist Brook Andrew observes, “There is an urgent need for First Nations peoples to control their representation, both contemporary and historical, and for Indigenous knowledge to be recognised. For too long, negative or romantic representations of First Nations peoples have proliferated in primitivist discourse and museum displays to naturalise the colonial project and its aftermath…”12 According to a friend who works in a museum in New Zealand, “It would be fair to say that, despite us having the Treaty of Waitangi, there is still a lot of cultural trauma here. There are lots of attempts at redress, and strong work being done by contemporary Māori artists (including photographers) to reinterpret colonial views, give voice to the harm done, and find ways to move forward.”13

She continues, “Outside of the museum/gallery, in local marae (meeting houses), photographs of ancestors are a way to connect with them quite tangibly. This is positive. Most marae display photographic portraits illustrating the whakapapa (geneaology/lineage) of their iwi (tribe) and hapu (sub-tribe). Some have many photos hung along all the walls of the whare, and others are only brought out for tangihanga (funerals). Photographs are often removed from the wall and travel to other marae for big events. So on a vernacular as well as a ritual/spiritual level, they have an important and valued role invoking the presence of people now departed.”

There is never a definitive answer to these complex questions and the ground will forever remain contested terrain, full of the possibilities of re-territorialisation and remembering. But this visual language of race can be reinterpreted with respect, honour and grace, serving “as inspiration for artistic production in New Zealand that centres Indigenous frameworks, concepts, and worldviews” that prioritise storytelling and lived cultural practices which elaborate “the Māori values and principles that should underpin both academic and community research, particularly where photography is concerned.”14 Yes, simply yes!

The photographic portraits by Harding of Māori emphasise the fact that their story is not one of the distant past but is one of “a present-day reality populated by real people with mana, knowledge, history, integrity, and a legitimate grievance against the Crown’.15 “As Christopher Morton and Elizabeth Edwards have demonstrated, the medium [photography] is defined by its incessant ‘recodability’ and, while photographs have been valued for recording a past moment, photographic images also perform in the present, often in unexpected ways. When it comes to legacy images, I can examine the conditions around their making, but I can also consider their contemporary uses and meanings. This is a method of rewriting history to account for Indigenous loss and survival, and also to think through the absences in the photographic record.”16

“In Roland Barthes’s words, it is ‘that someone has seen the reference […] in flesh and blood‘. The relation between metal compounds and light in analogue photography means they are an ’emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here’. Ethnographic photographs can reveal trauma, when viewers connect with the bodily presence of those photographed, recognise a life that matters, and implicate themselves in the history of dispossession. However, the trauma includes the violent framing of First Nations peoples.”17

“In sum, for Aboriginal and Māori artists and communities, photographic archives offer a rich source of history, counter silence and exclusion, and provide a means to explore many issues that remain in the present. Archival images are tangible and powerful relics that provide a link with the past and bring it concretely into our time. This is the power of photographs: to address absence, to reconnect relatives with each other and to Country, and to heal. As Wiradjuri scholar Lawrence Bamblett argues, photographs link people in the present, as well as connecting them to places and the past; they ‘fit into the joyful scene of people telling stories’. The history of broken families and the dispossession and control of Aboriginal people remain contested, and often absent, from national stories and visual histories, but these silences are filled by the solidity and presence of photographs.”18

To me, the saddest photograph in the posting is that of an Unidentified young maori girl (Between 1856-1889, below) in which the unknown has a traditional hairstyle yet wears Western clothes (some Māori disdained to wear a Pākehā garment when being photographed) and has a crucifix around her neck. The pensiveness of the hands and the desolate look on her face says it all… they speak of sadness “not because of what she’s doing or where she is, but something ages ago, like there is a long, long deep sadness.”

And yet the strongest photographs of Māori women are two other portraits: in one, Unidentified young Maori woman with clear chin moko (1870-1889, below), the unknown wears Western dress but stares comfortably, defiantly at the camera displaying her clear chin moko (her heritage, her culture) with her hands relaxed on her lap, her presence undeniable / her undeniable ‘presence’; and in the other, Unidentified Māori woman (c.1880, below), the unknown also wears Western dress and stares determinedly at the camera (that stare reaching through the centuries), the white-tipped tail feather of the huia in her long natural hair (these feathers were prized above all others as head adornments, and signified chiefly status) – her ringed hand resting comfortably across her chest, the hand over the heart a gesture emblematic of honesty, she displays her tā moko tattoo, a unique expression of her cultural heritage and identity.

Present, alive, full of energy, an emanation of the referent, a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here.

From past into present into future.

From past time into present time into future time.

From past (representation) into present (reclamation/reconfiguration) into future (change).

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ Fiona Oliver. “Off the record | William Harding, ‘photographist’,” on the National Library website July 28th, 2022 [Online] Cited 23/08/2022

2/ Ibid.,

3/ For more photographs of men and pairs of men by William Harding please see Stephen O’Donnell. “Young gentlemen of Whanganui – photographs from the studio of William James Harding, New Zealand, circa 1856-1889,” on the Gods and Foolish Grandeur blog, Sunday, May 30, 2021 [Online] Cited 20/10/2022

4/ Email to the author, 1st June 2018 from Executive Director Shannon Keller O’Loughlin (Choctaw) of the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA)

5/ Anonymous. “New Zealand,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 18/10/2022

6/ Anonymous. “Māori culture,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 18/10/2022

7/ Elizabeth Edwards and Christopher Morton, ‘Introduction’, in Photography, Anthropology and History: Expanding the Frame, ed. Christopher Morton and Elizabeth Edwards, Farnham: Ashgate 2009, pp. 1-24 footnoted in Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla. ‘Editorial’, in History of Photography Volume 42, 2018 – Issue 3: Indigenous Photographies. Guest Editors: Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla, pp. 213-216

8/ Michael King. Māori: A Photographic and Social History. Wellington: Reed 1996, p. 2 quoted in Helen Brown (2018) “‘I Depend More on Photographs to Help Me Along’: The Ngāi Tahu Portraits in Lore and History of the South Island Maori,” in History of Photography, Volume 42, 2018 – Issue 3: Indigenous Photographies. Guest Editors: Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla, pp. 288-305

9/ See Roger Blackley. Galleries of Maoriland: Artists, Collectors and the Māori World, 1880-1910. Auckland University Press, 2018

10/ See Jane Lydon and her important books Eye Contact: Photographing Indigenous Australians (2005) and Photography, Humanitarianism, Empire (2016) where she unpacks the historical baggage of the colonial portrait photography of Indigenous Australians and notes that the photographs were not solely a tool of colonial exploitation. Lydon articulates an understanding in Eye Contact that the residents of Coranderrk, an Aboriginal settlement near Healsville, Melbourne, “had a sophisticated understanding of how they were portrayed, and they became adept at manipulating their representations.”

11/ Roger Blackley Op cit.,

12/ Brook Andrew & Jessica Neath (2018). “Encounters with Legacy Images: Decolonising and Re-imagining Photographic Evidence from the Colonial Archive,” in History of Photography, Volume 42, 2018 – Issue 3: Indigenous Photographies. Guest Editors: Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla, pp. 217-238

13/ “Artists draw upon the archive to retell or transform national histories that have omitted or denigrated Indigenous people.6 In addition, Indigenous photographers have provided a new perspective on past and present by revealing marginal experiences, asserting Indigenous capacity and addressing the losses and fractures of historical processes such as assimilation.”

Jane Lydon. ‘Transmuting Australian Aboriginal Photographs’, World Art, 6:1 (2016), pp. 45-60; and Ashley Rawling, ‘Brook Andrew: Archives of the Invisible’, Art Asia Pacific, 68 (May/June 2010), pp. 110-17, footnoted in Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla. ‘Editorial’, in History of Photography Volume 42, 2018 – Issue 3: Indigenous Photographies. Guest Editors: Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla, pp. 213-216

14/ Elizabeth Edwards and Christopher Morton, ‘Introduction’, in Photography, Anthropology and History: Expanding the Frame, ed. Christopher Morton and Elizabeth Edwards, Farnham: Ashgate 2009, pp. 1-24 footnoted in Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla. ‘Editorial’, in History of Photography Volume 42, 2018 – Issue 3: Indigenous Photographies. Guest Editors: Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla, pp. 213-216

15/ Ibid.,

16/ Brook Andrew & Jessica Neath (2018). “Encounters with Legacy Images: Decolonising and Re-imagining Photographic Evidence from the Colonial Archive,” in History of Photography, Volume 42, 2018 – Issue 3: Indigenous Photographies. Guest Editors: Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla, pp. 217-238

17/ Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1981), London: Vintage 2000, pp. 79-80 (original emphasis) quoted in Brook Andrew & Jessica Neath (2018). “Encounters with Legacy Images: Decolonising and Re-imagining Photographic Evidence from the Colonial Archive,” in History of Photography, Volume 42, 2018 – Issue 3: Indigenous Photographies. Guest Editors: Jane Lydon and Angela Wanhalla, pp. 217-238

18/ Elizabeth Edwards and Christopher Morton Op cit.,

Many thankx to the National Library for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Book cover of Mates and Lovers: A History of Gay New Zealand by Chris Brickell which is a Harding image.

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Two unidentified men

c. 1888

Glass negative

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Please note: photograph not in exhibition.

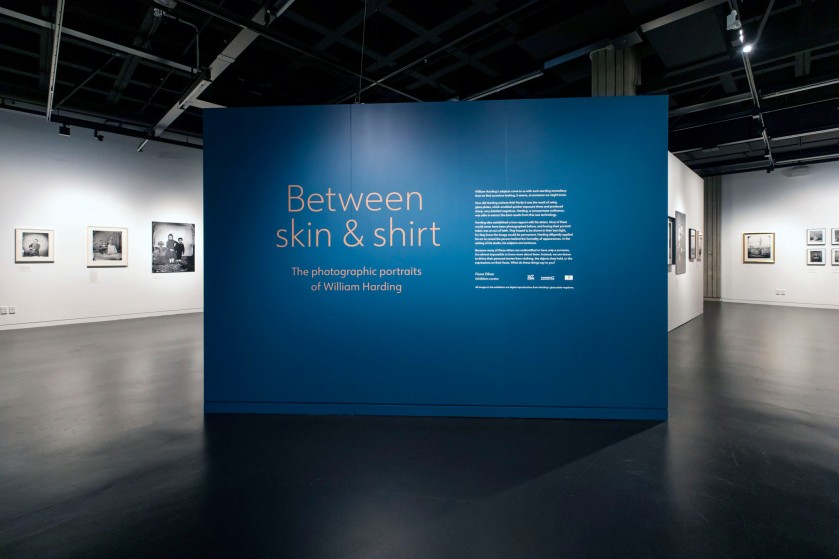

Installation views of the exhibition Between skin & shirt: The photographic portraits of William Harding at the National Library of New Zealand Gallery, Wellington

Photographer: Mark Beatty for Alexander Turnbull Library Imaging Services

Looking at Harding’s portraits

French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson said that ‘The most difficult thing … is a portrait. You have to try and put your camera between the skin of a person and his shirt’. William Harding achieves just that. Harding diligently applied his art to reveal the person behind the formality of appearances. In the setting of his studio, his subjects are luminous.

The portraits in this exhibition have been selected from the nationally significant Harding collection of over 6,500 glass-plate negatives held by the Alexander Turnbull Library. The photographic portraits William Harding took in his Whanganui studio from the 1850s to the 1880s come to us with such startling immediacy that we find ourselves looking, it seems, at someone we might know.

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Reardon child

c. 1870s

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Master Percival Thomas Scott and his sister, of Feilding

April 1878

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Photograph taken by the studio of William James Harding, Whanganui. Accession register gives girl’s name as Elizabeth Jane or Annie Scott and her age as 6 years. Percival’s age is given as four years.

Installation view of the exhibition Between skin & shirt: The photographic portraits of William Harding at the National Library of New Zealand Gallery, Wellington showing at left, [Miss] Scott (Between 1870-1889, below); at second left, Woman on left wearing large crinoline dress with black jacket with tassels and belt above the waist, woman on the right wearing crinoline dress with tassels on top part of dress (Between 1870-1880, below); at centre, Lieutenant Herman with his ventriloquist dummy (c. 1877, below); and at second right, Members of the Burne family (Between 1856-1889, below)

Photographer: Mark Beatty for Alexander Turnbull Library Imaging Services

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Lieutenant Herman with his ventriloquist dummy

c. 1877

Wet collodion glass negative

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Lieutenant Herman (b. 1855), whose real name was Thomas Martin Powell, advertised his performances in New Zealand newspapers from 1877-1882, touring here and in Australia alongside William H. Thompson’s American and Zulu war dioramas. He poses in this portrait with his dummy, but also exercised his powers of ventriloquism through the character of a sock with a face drawn on it.

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified Māori woman

c. 1880

Glass negative

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Half length portrait of an unidentified Maori woman wearing European clothing and holding her hand to her chest. She wears a white tipped feather in her hair, ear adornments, a tiki around her neck, and a ring on one of her fingers. She has a facial moko.

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified woman

Between 1870-1899

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Many of Harding’s portraits show a directness not associated with Victorian period. Many of his sitters, like this one, show weathered and freckled skin, illustrating the hardships of colonial life.

William Harding: An unconventional eye

Fiona Oliver, Curator of the Between Skin & Shirt exhibition, writes about William Harding and his photographic practice including thoughts on why there was no smiling in formal Victorian portraiture. …

First photographs

The first photographic studios opened in New Zealand in 1848 – J. Polack and J. Newman in Auckland, and H.B. Sealy in Wellington, making daguerreotypes. The collodion wet-plate process was invented in England in 1851 and just five years later, in Whanganui, William Harding set up his studio producing these glass-plate negatives.

An early adopter, he was also a real craftsman; having previously worked as a coach builder and cabinetmaker, he now turned his hand to making his own cameras and grinding his own lenses. His portraits were commissioned and many were intended for cartes de visite (calling cards), which had become popular. The emulsified and peeling edges seen in the Harding negatives would have been cropped out of the finished photograph.

Say ‘prunes’!

Most of Harding’s sitters would never have been photographed before, and having their portrait taken was an act of faith. They hoped to be shown in their best light, for they knew the image would be permanent. Convention dictated what facial expressions were acceptable. Despite not smiling, Harding’s subjects are full of expression.

Smiling was not usually done in formal Victorian portraiture, including Harding’s. Some argue it was because of the state of everyone’s teeth, but the convention came from painting, where only fools and drunks were shown to be grinning. It was Mark Twain who wrote: ‘A photograph is a most important document, and there is nothing more damning to down in posterity than a silly, foolish smile caught and fixed forever’. So instead of saying ‘cheese’, sitters were encouraged to say ‘prunes’, to create the effect of a small, perfect, mouth.

Harding’s sitters are also largely unsmiling. But their faces are alight, staring down the camera, eyes aflame. Sometimes they look peevish, bored or exhausted. There seems to be little inclination towards idealisation. Harding refused to retouch his photographs as other commercial photographers did. Faces are weathered and freckled; clothing is often ragged, mended or borrowed. Wealthier clients look more poised, but even they have been captured in a moment where the mask of formality seems to have slipped. Harding seems to get beyond the rigidity of convention, his faces coming to us with honesty and startling immediacy.

Strike a pose

In Victorian photography, a sitter was usually arranged to highlight their best features and disguise any aspect that might be considered, by the standards of the time, unsightly. Harding didn’t seem to go in for that. There is little idealisation or subterfuge: a crippled child is shown wearing her callipers; a Down’s syndrome child is held on her mother’s lap; a man with a sheen of sweat lies on his deathbed. …

Props

Most props were supplied by the studio, but some sitters brought their own. Such props were used to convey something about the sitter. Some were common conventions; for example, a book held in the hand indicated literacy at a time when not everyone could read. Posing with a small framed photographic portrait indicated a need to remember someone who was otherwise absent. Children often posed with a favourite toy, and men with an object that represented the job they did and their status in society.

This unidentified Māori woman, c. 1870-1889, poses with a vignette of personal, not studio props, including a faux Greek vase, a book, a cameo brooch, a hat with an ostrich feather, and a box. She makes her wedding ring evident to indicate her married status.

In many of Harding’s portraits, we see the same props turn up over and over again, including a rocking horse, a statuette of a child, a stereoscope, a vase, and a side table with barley-twist legs. Men hold flowers – why would this be? Soldiers hold their rifles, or, if they played in a military band, their musical instruments. Perhaps needing something to do with an awkward pair of hands, some hold a hat, bag or clutch at a piece of furniture. The same oversized and overstuffed chaise longue is leaned, climbed or sat on by many of Harding’s subjects.

Painted backdrops

As well as pieces of furniture, the studio offered a selection of painted backdrops in front of which sitters were arranged. In Harding’s studio they depicted, for example, a scene through a window of a church steeple set in bucolic abundance, the interior of a stately home, and an archway beyond which lies Roman columns and trees. These came with the addition of artificial plants, a balustrade, plinths, patterned flooring and heavy drapes.

This might all sound opulent – but there is a shabby look to much of it. In some cases the painted backdrops are on a slight lean, or are crumpled. And because these are uncropped images, we see unused props and other studio paraphernalia cluttered at the edges. The artifice is fascinating, perhaps because it is in such contrast to the authenticity with which Harding depicts his subjects.

Fiona Oliver

Fiona is an Exhibition Advisor at the National Library. She was formerly the Curator of New Zealand and Pacific Publications at the Alexander Turnbull Library.

Fiona Oliver. “William Harding: An unconventional eye,” on the National Library website August 17th, 2022 [Online] Cited 23/08/2022

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified young man (Mr Aubert?) in military uniform, with cap

Between 1870-1899

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Mr G Willis

April 1884

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Mr Plampin

17 August 1883

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Reverend Richard Taylor’s chair, with other Māori artefacts

Between 1856-1899

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Reverend Richard Taylor’s chair, with other Maori artefacts. Shows a wooden chair carved with Māori motifs. Three staffs are behind it. On the left is a tewhatewha, and on the right, a taiaha. A patu is balanced on the central back panel. On the seat are two waka huia. A gourd is on the floor. Photograph taken between 1856-1889, by William James Harding.

“Curios might be excavated, purchased, even stolen from burial caves, but the usual way in which they moved from Māori to Pākehā hands was through gifting. Gifts forced the basis of the outstanding collections, including those accumulate by Grey and Mair, but this was also how innumerable farmers, lawyers, churchmen and politicians obtained their Māori treasures. In the Māori world, such gifting embodied reciprocal debt and important taonga were expected to be returned at auspicious occasions or in turn gifted on to further recipients, together with their kõrero (provenance). Having arrived in Pākehā ownership, however, tango became commodities – objects with market value – and only rarely returned to the original givers.”

Roger Blackley. ‘Introduction’ in Galleries of Maoriland: Artists, Collectors and the Māori World, 1880-1910. Auckland University Press, 2018

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Fraser [Consump?]

Between 1856-1899

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified Maori man, with moko, Whanganui district

1860s

Glass negative

6.5 x 8.5 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified man, sick in bed

1870-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Off the record | William Harding, ‘photographist’

For the first time, the photographs of William Harding (1826-1899) are featured in a major exhibition Between skin & shirt: The photographic portraits of William Harding.

Importance of William Harding photographs

The collection of William Harding’s glass-plate negatives – over 6,500 in total – is undoubtedly of national importance. His portraits provide a detailed picture of Whanganui society from the 1850s to the 1880s, and are a rich source of information relating to Māori and Pākehā individuals and their relationships at a formative time in this country’s history. But what really makes the photographs special is not their broader significance, nor their number, but the minutiae of detail evident in each one of them. Every image depicts its subjects with such depth and nuance that we find ourselves looking, it seems, at people we might know.

Portraits immediate and relatable

The faces are immediate and relatable, despite having been photographed over 140 years ago. How did Harding achieve this striking effect? Firstly, the glass plates he used produce a sharper, more stable and detailed negative than paper. In addition, Harding’s work was what his daughter Lydia described as unerringly ‘faithful’. That is to say, he was interested most of all in authenticity.

Unlike other commercial photographers, Harding embellished his studio with only a small repertoire of props and backdrops, and wouldn’t retouch his photographs to flatter his sitters. But in the shabby setting of his studio, his subjects are luminous. The women, men, children, families and other groups who sat for him are shown with sensitivity and honesty. We are drawn to the contemporaneity of their faces and in this way we make a connection with the person.

William Harding ‘photographist’

Harding’s methods may have been unconventional because he refused to compromise his art to make money. He’d come to New Zealand from England as a coachbuilder in 1855, along with his wife Annie. He tried his hand at cabinet-making, and in 1860 set up a photographic studio in Ridgway St, Whanganui. Clever at whatever he turned his hand to – an autodidact with a prodigious memory, he could quote the Bible at will, build telescopes and make his own cameras – his lack of financial motivation meant that the family relied on Annie’s earnings as a teacher to get by. Unlike the landscapes he much preferred to photograph, portraits at least provided some regular income – and we can be thankful they did, or he would not have produced so many.

Up close to a diverse cast of characters

This exhibition of Harding’s portraits, reproduced at much larger scale from the original negatives, gives us chance to get close to a diverse cast of characters. Sometimes it seems that those characters are watching us. In the mutual exchange, time and space appear to dissolve. As photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson has said: ‘The most difficult thing … is a portrait. You have to try and put your camera between the skin of a person and his shirt’ – Harding achieves just that.

Fiona Oliver. “Off the record | William Harding, ‘photographist’,” on the National Library website July 28th, 2022 [Online] Cited 23/08/2022

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified woman

Between 1856-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

[Mrs?] Keen

Between 1870-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified young maori girl

Between 1856-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Mrs Gillen

1870s

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

[Miss] Scott

Between 1870-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified young Maori woman with clear chin moko

1870-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Woman on left wearing large crinoline dress with black jacket with tassels and belt above the waist, woman on the right wearing crinoline dress with tassels on top part of dress

Between 1870-1880

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified family group

1870-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Members of the Burne family

Between 1856-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Captain Nathaniel Flowers and wife Margaret, with a dog

1878

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

Nathaniel Flowers, a British Army soldier, and Margaret Murch, married on St Helena during his posting there in the 1840s. Margaret was likely a freed slave living on the island. In the 1850s, Nathaniel was sent to New Zealand with his wife and son, eventually leaving the army and settling in Whanganui, where he worked as a labourer and harbour-board signalman – the spyglass he’s holding would have been used to look for ships coming over the horizon, before signalling to them whether it was safe to enter port. The couple’s relationship hit rough seas in the years after this photograph was taken. In 1891 Margaret was arrested for being drunk and disorderly, and later that year Nathaniel applied for an order to prohibit her from buying alcohol before being charged himself with not providing for his wife.

Exhibition label

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified Maori man and his son

1870-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified Wanganui family and their possessions

c. 1870s

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899)

Unidentified men and women

Between 1856-1889

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

National Library of New Zealand, Wellington

Corner Molesworth & Aitken St

Phone: 0800 474 300

Opening hours:

Monday – Friday: 9am – 5pm

Saturday: 9am – 1pm

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Between skin & shirt: The photographic portraits of William Harding' at the National Library of New Zealand Gallery, Wellington showing at left, '[Miss] Scott' (between 1870-1889); at second left, 'Woman on left wearing large crinoline dress with black jacket with tassels and belt above the waist, woman on the right wearing crinoline dress with tassels on top part of dress' (between 1870-1880); at centre, 'Lieutenant Herman with his ventriloquist dummy' (c. 1877); and at second right, 'Members of the Burne family' (between 1856-1889) Installation view of the exhibition 'Between skin & shirt: The photographic portraits of William Harding' at the National Library of New Zealand Gallery, Wellington showing at left, '[Miss] Scott' (between 1870-1889); at second left, 'Woman on left wearing large crinoline dress with black jacket with tassels and belt above the waist, woman on the right wearing crinoline dress with tassels on top part of dress' (between 1870-1880); at centre, 'Lieutenant Herman with his ventriloquist dummy' (c. 1877); and at second right, 'Members of the Burne family' (between 1856-1889)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/20220525_nl_pe_ge_between_skinshirt_opening_003.jpg?w=840)

![William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) 'Fraser' [Consump?] Between 1856-1899 William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) 'Fraser' [Consump?] Between 1856-1899](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/harding-fraser-consump.jpg?w=650&h=843)

![William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) '[Mrs?] Keen' Between 1870-1889 William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) '[Mrs?] Keen' Between 1870-1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/harding-mrs-keen.jpg?w=650&h=851)

![William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) '[Miss] Scott' Between 1870-1889 William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) '[Miss] Scott' Between 1870-1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/harding-miss-scott.jpg?w=650&h=850)

You must be logged in to post a comment.