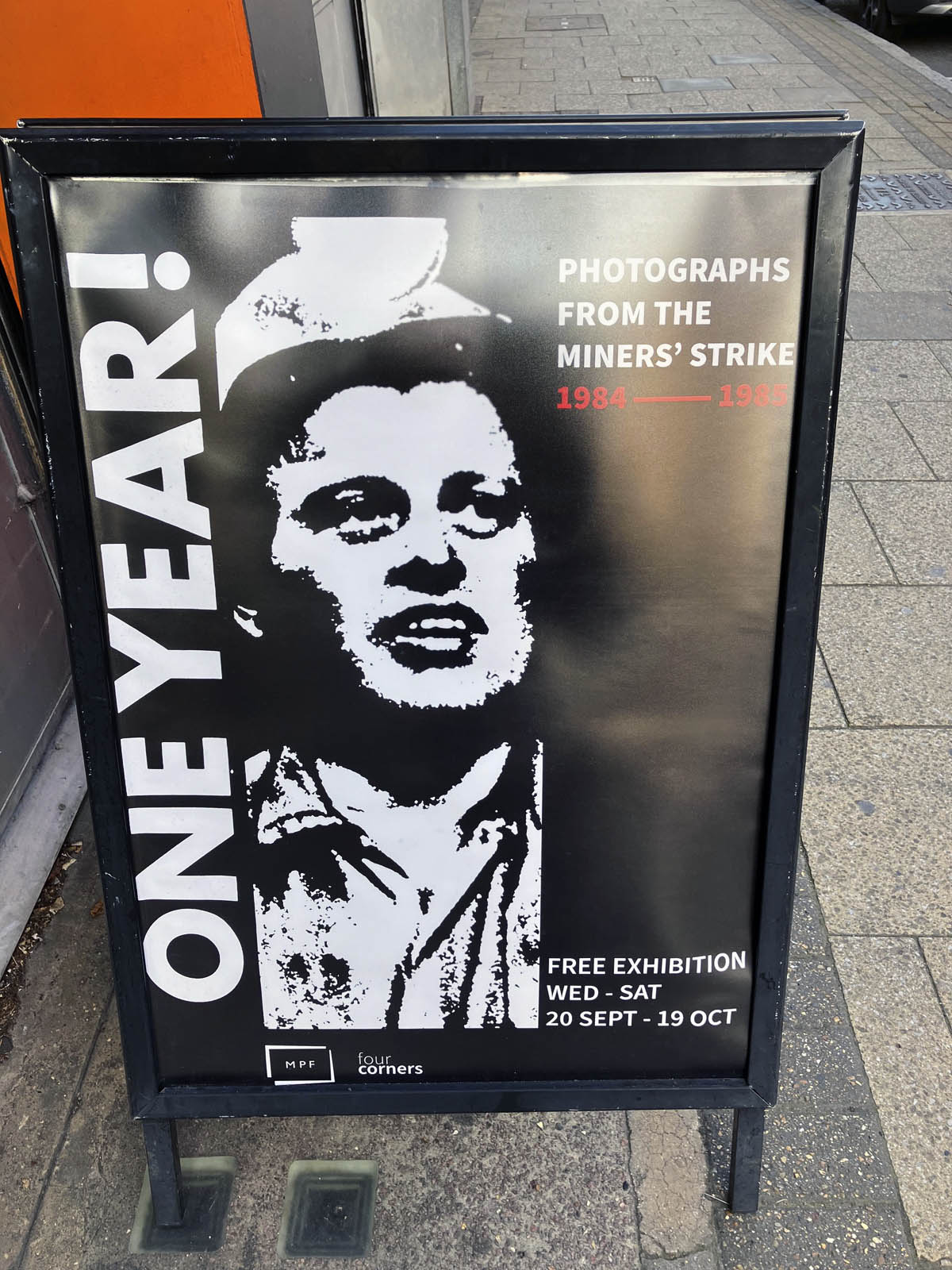

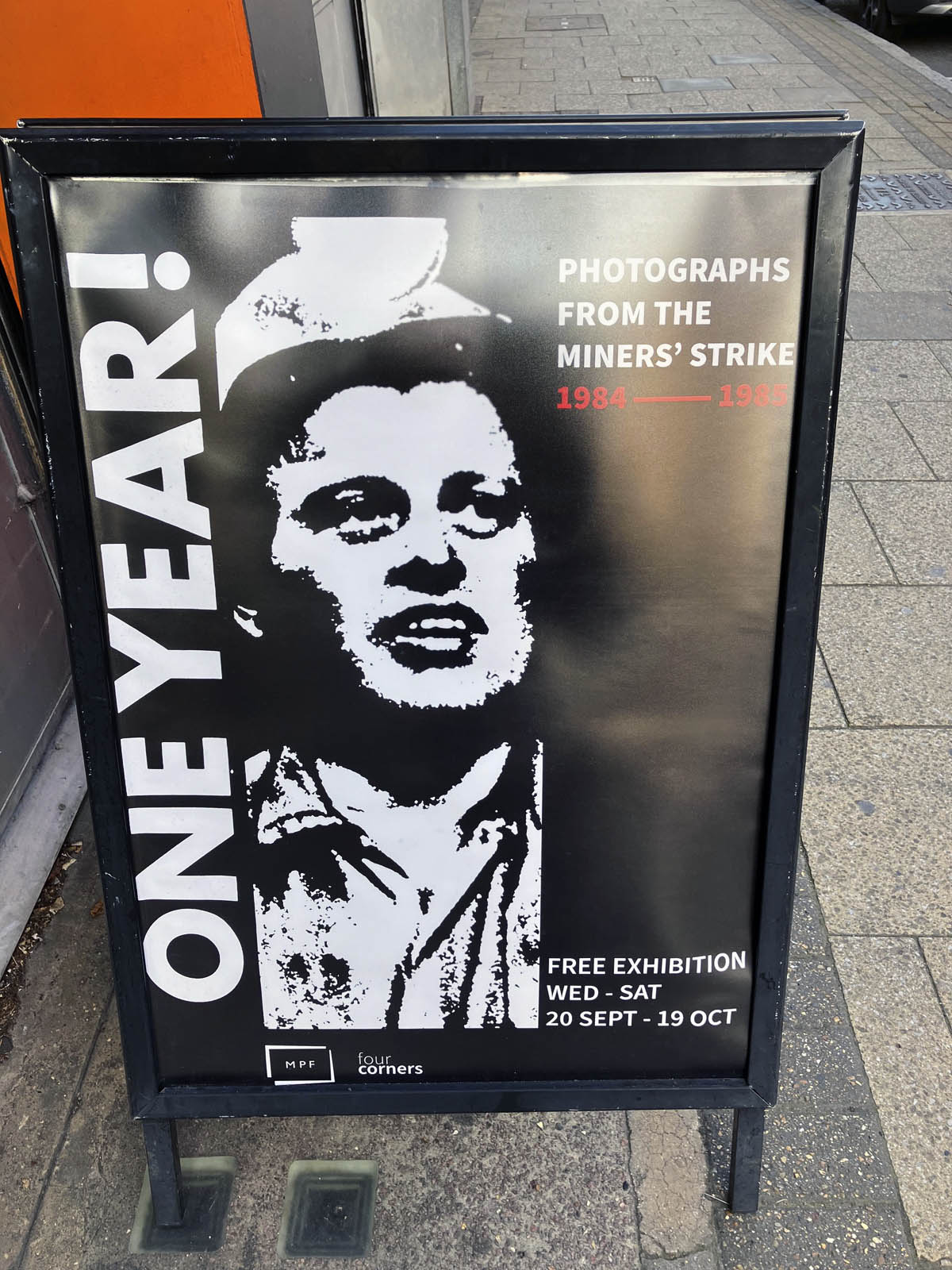

Exhibition dates: 20th September – 19th October, 2024

Curator: Isaac Blease

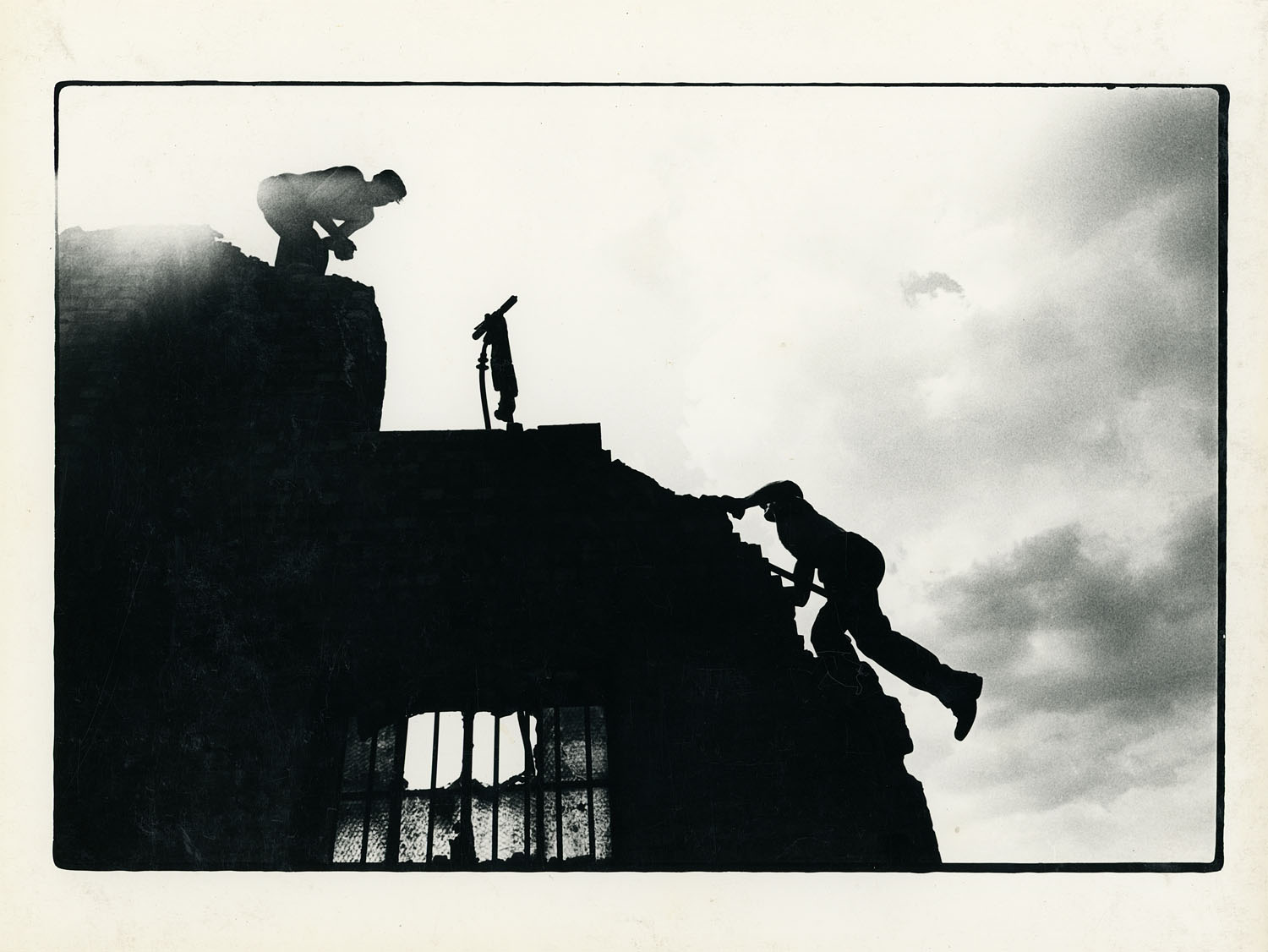

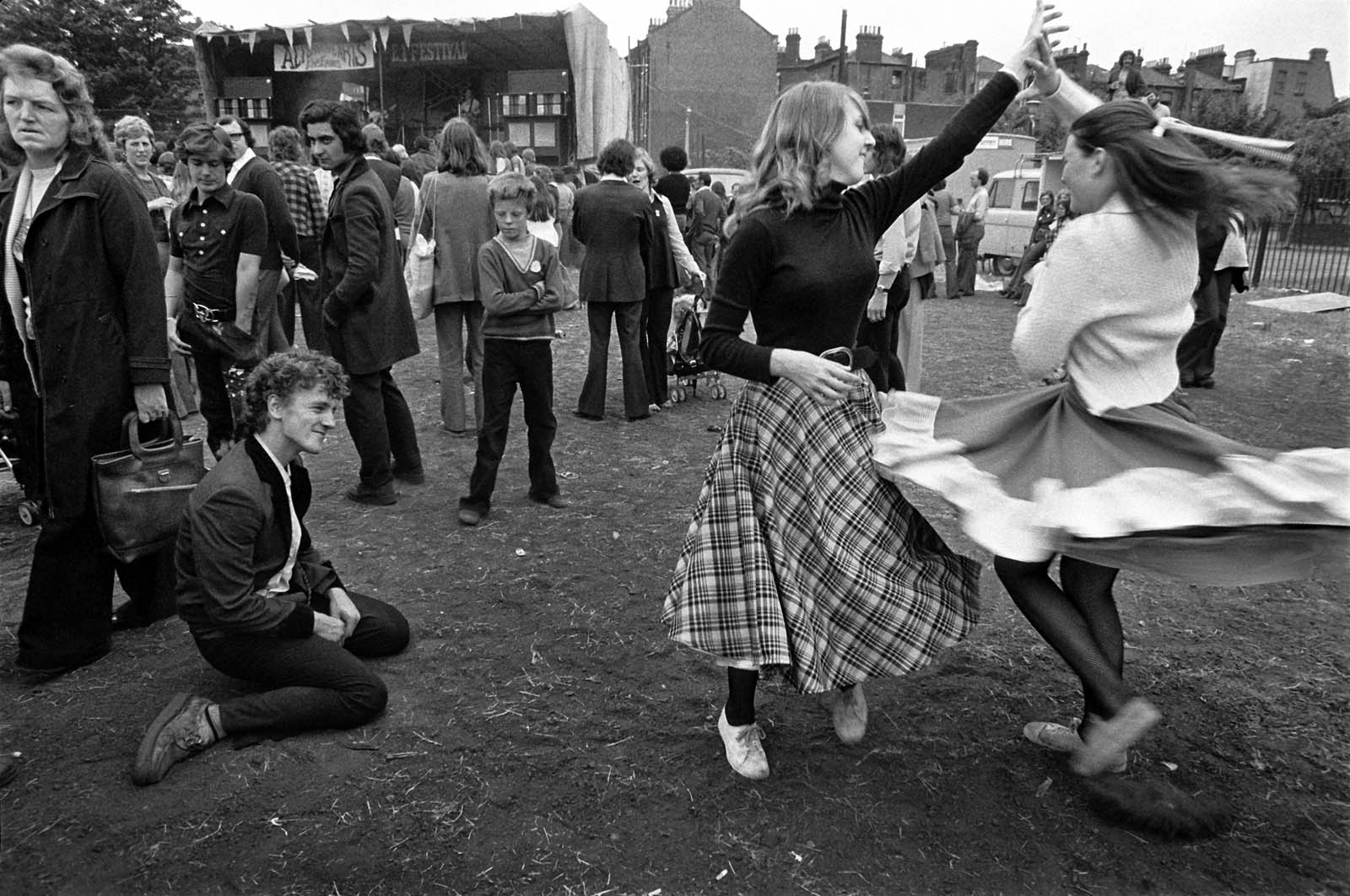

Chris Killip (British, 1946-2020)

Durham Miners’ Gala

1984

Gelatin silver print

© Chris Killip Photography Trust – Magnum Photos

This is another excellent exhibition with a social conscience from Four Corners, ably supported by the Martin Parr Foundation.

THE LEGACY: “The strike was lost, Scargill defeated. But the greatest losers were not just the miners, but the whole labour movement which soon found itself trampled by the global restructuring of business by Thatcher and her successors on both sides of the Atlantic.

Workers in Britain and the world would soon awake to the reality of the new Thatcher – and Reagan – industrial revolution; a huge rise in ‘compensation’ for a few executives, and gutted workplaces, leading to low-paying McJobs for the rest.”

Audsley Edwards

Losers and losers

Pardon my language but, in a guttural English accent, I declare Thatcher and her minions, police and media, bastards … bloody bastards!

Her name still sends shivers down my spine. Vindictive, unbending, inhuman.

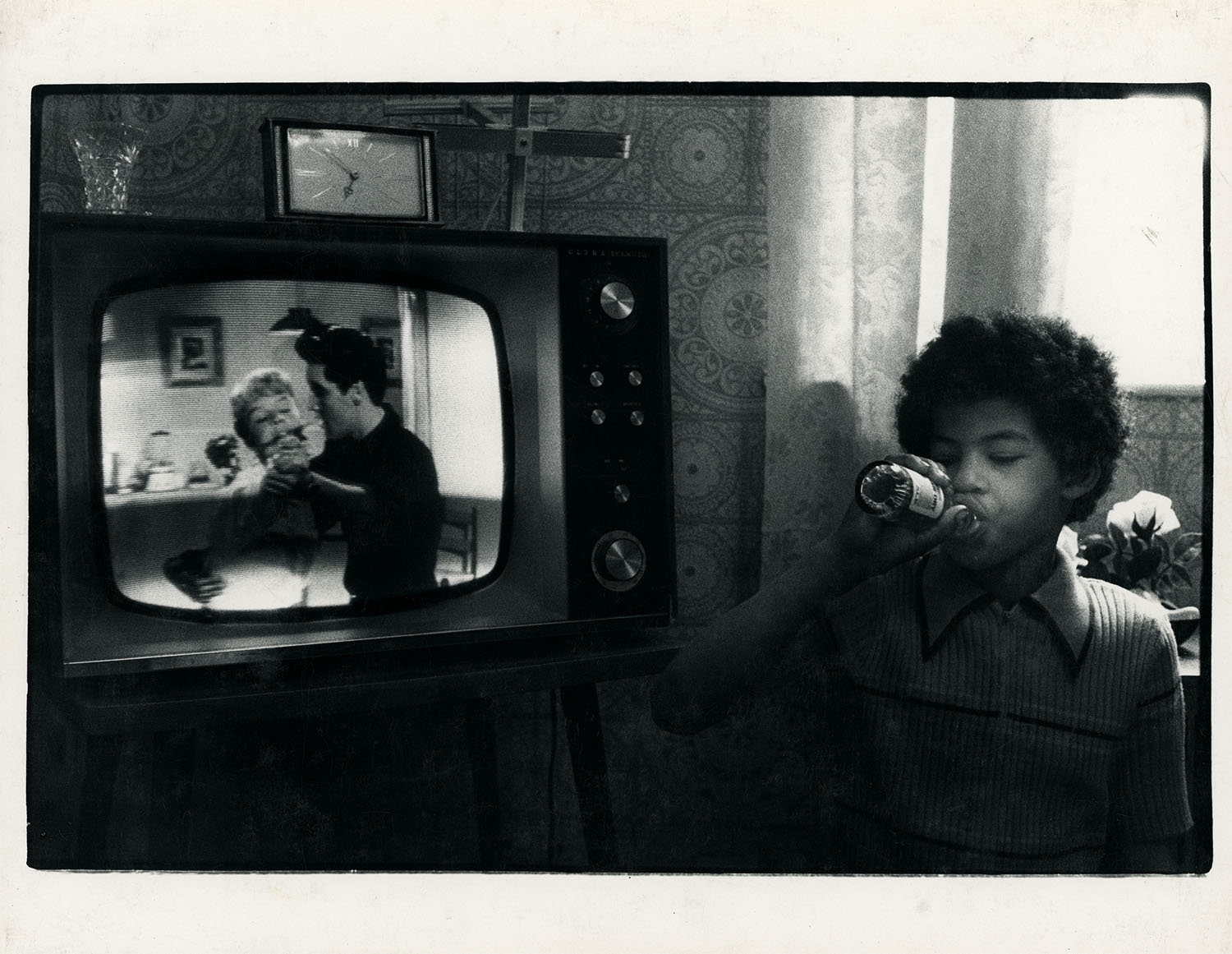

Class warfare has never been far from the surface in British society. Upstairs downstairs, the haves and the have nots. New wealth devolved from the British Industrial Revolution 1750-1900 (which produced machine-made, mass produced goods) used man power and child power – in the factories, down the pits.

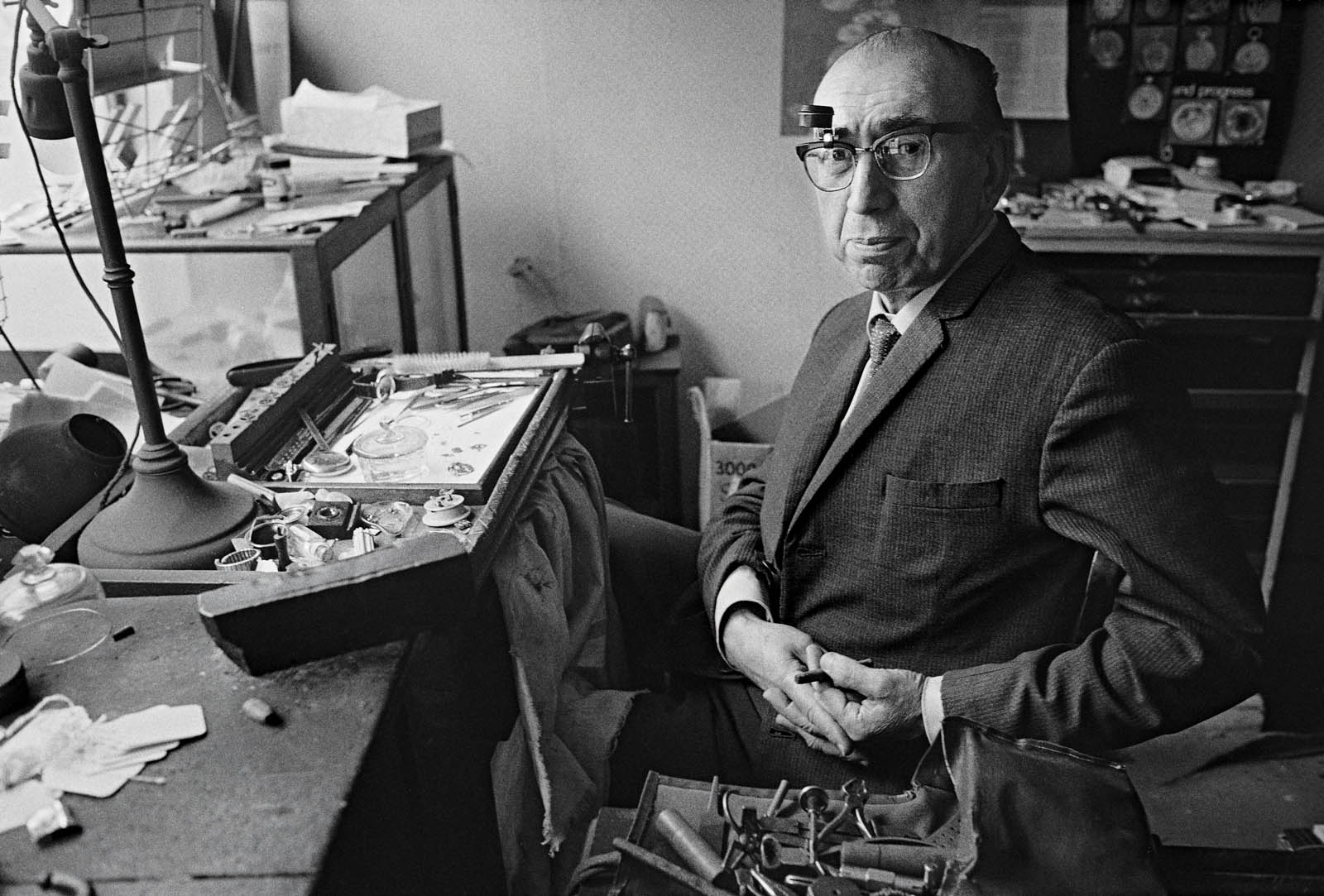

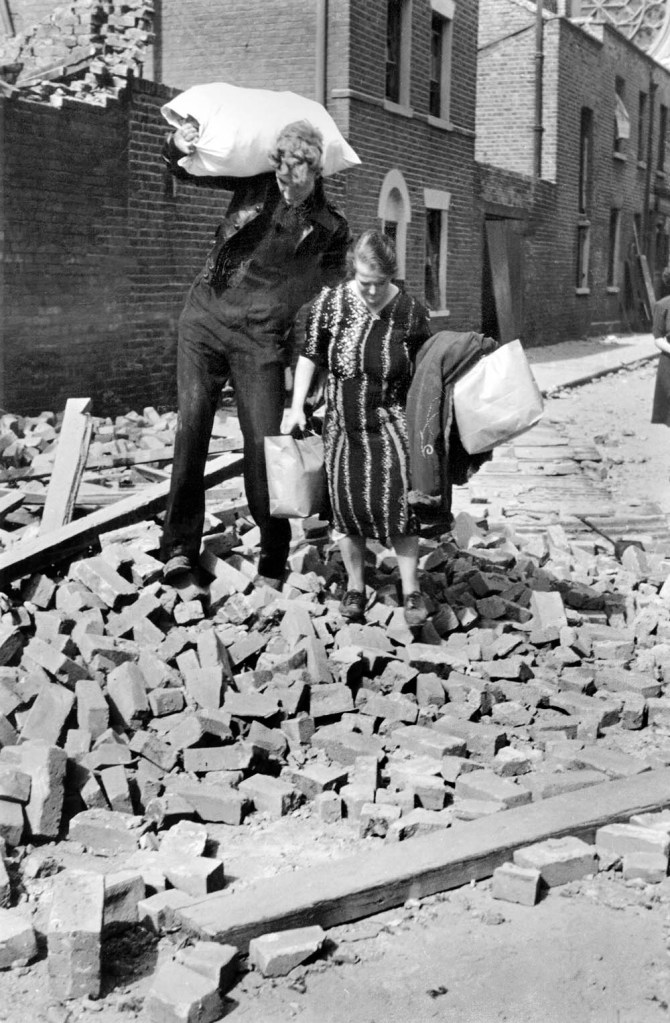

Trade unions were legalised in 1871 in the UK and sought to reform socio-economic conditions for people in British industries. They were especially strong in the coal mining industry. Coal mining in the UK has a long history dating back to Roman times and this history has long been celebrated, as can be seen in Bill Brandt’s photographs of the tough life of miners and their families (1937, below) and the ACKTON HALL COLLIERY commemorative plate (1985, below).

After the Second World War, “All the coal mines in Britain were purchased by the government in 1947 and put under the control of the National Coal Board (NCB).”1 Pit closures became a regular occurrence in many areas. “Between 1947 and 1994, some 950 mines were closed by UK governments.”1 “In early 1984, the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher announced plans to close 20 coal pits which led to the year-long miners’ strike which ended in March 1985.”2

“A strike was called by the Yorkshire region of the NUM in protest against proposed pit closures, invoking a regional ballot result from 1981. The National Executive Committee, led by Arthur Scargill, chose not to hold a national ballot on a national strike, as was conventional, but to declare the strike to be a matter for each region of the NUM to enforce. Scargill defied public opinion, a trait Prime Minister Thatcher exploited when she used the Ridley Plan, drafted in 1977, to defeat the strike. Subsequently, over several decades, almost all the mines were shut down.”3

“Scargill stated, “The policies of this government are clear – to destroy the coal industry and the NUM.” … This was denied by the government at the time, although papers released in 2014 under the thirty-year rule suggest that Scargill was right.”4

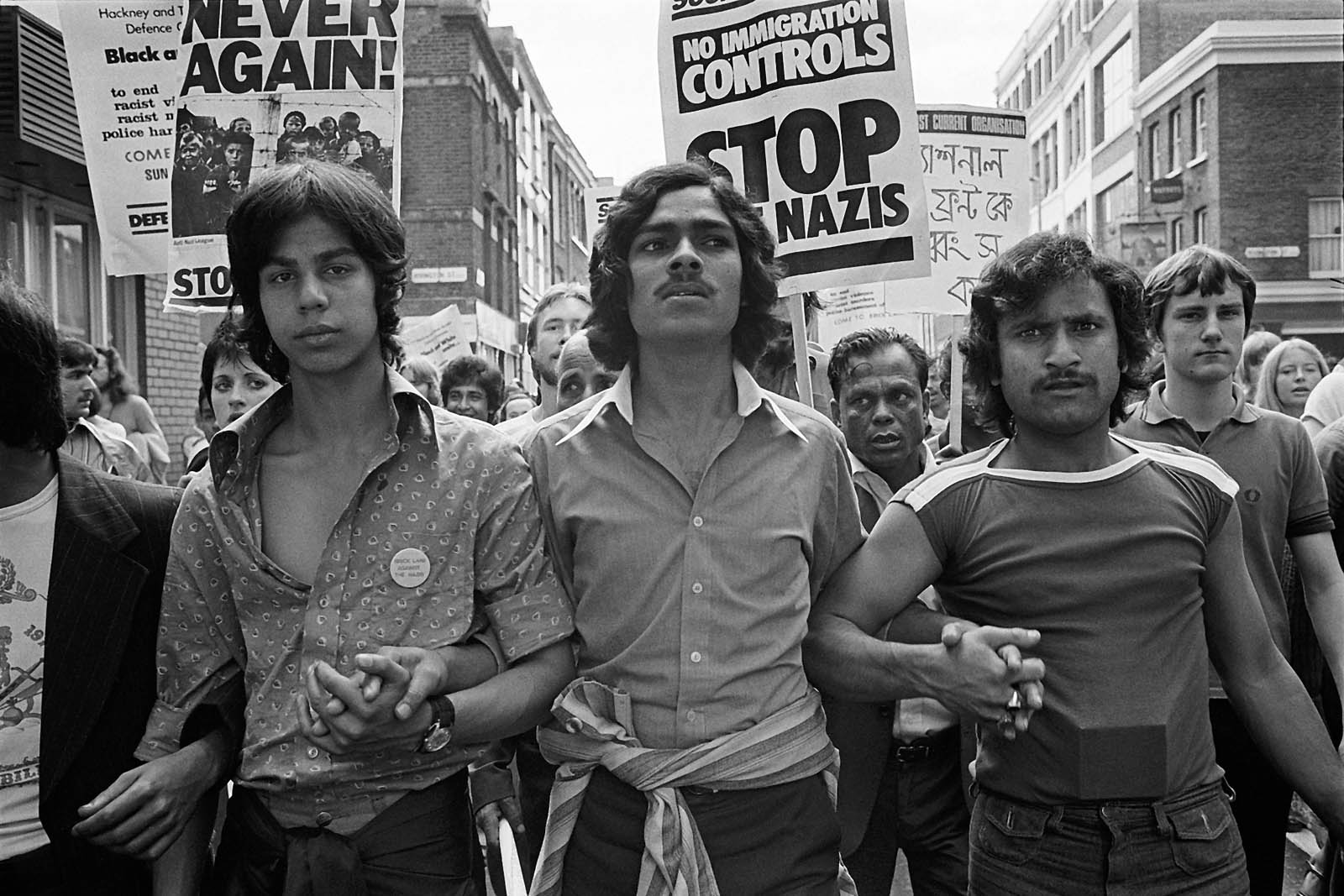

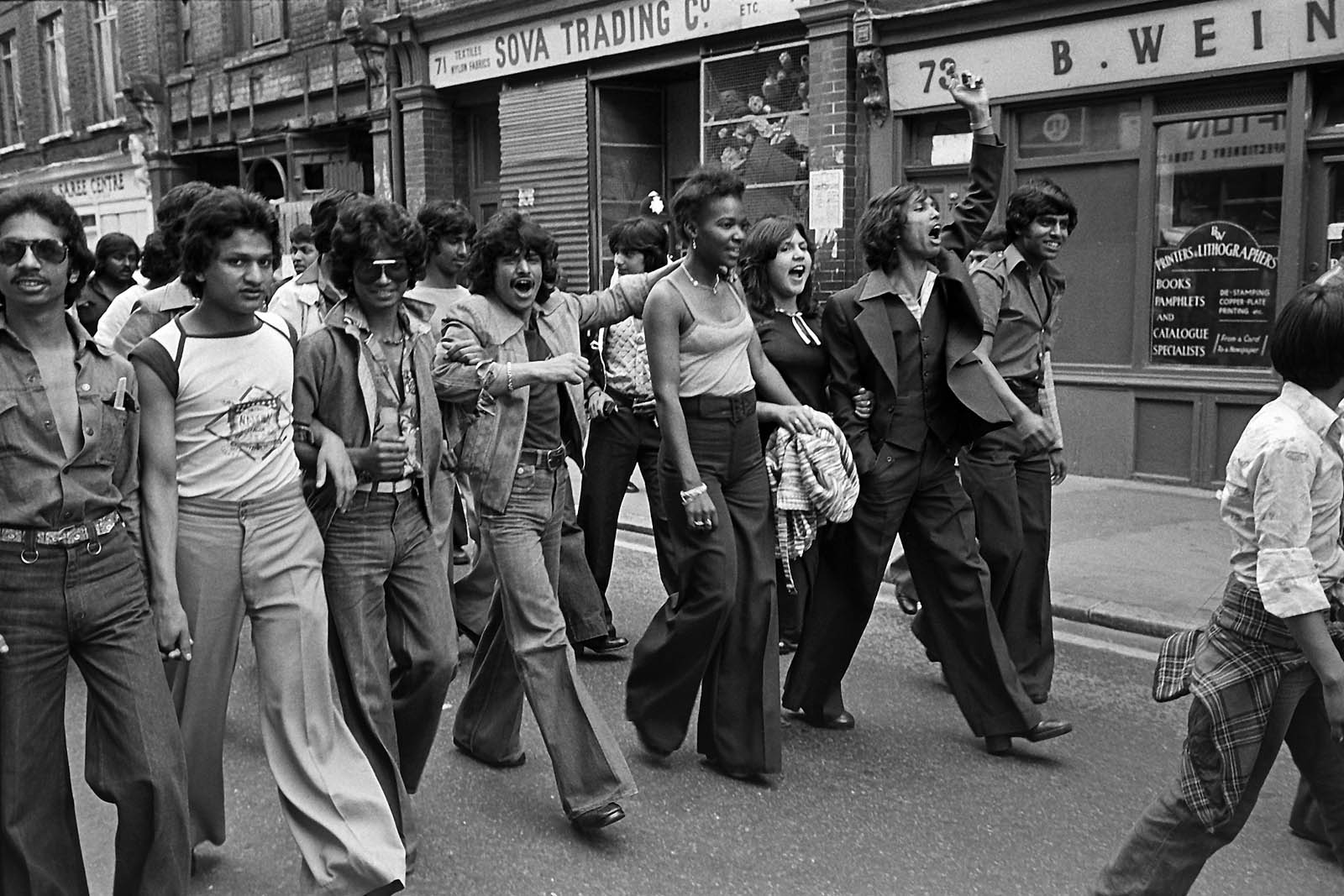

In the era of anti-Apartheid (in June 1984 Thatcher received a visit from P. W. Botha the South African premier), anti-war, pro abortion, nuclear disarmament, Gay Liberation, Women’s Liberation, Clause 28, anti-fascist marches and student protests – in the era of Thatcherism (“deregulation, privatisation of key national industries, maintaining a flexible labour market, marginalising the trade unions and centralising power from local authorities to central government”),5 Thatcher saw strong trade unions as an obstacle to economic growth through the implementation of neoliberal economic policies.

“Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency…. The organisation of labour and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers.”5

The losers from the Miners’ Strike were the working class communities and people of the mining villages… and the power of the unions. Thatcher wanted to destroy their power more than anything else and bugger the cost to communities and human beings. Their side of this conflict is portrayed in this exhibition through artefacts and photographs using photography as a tool of resistance.6

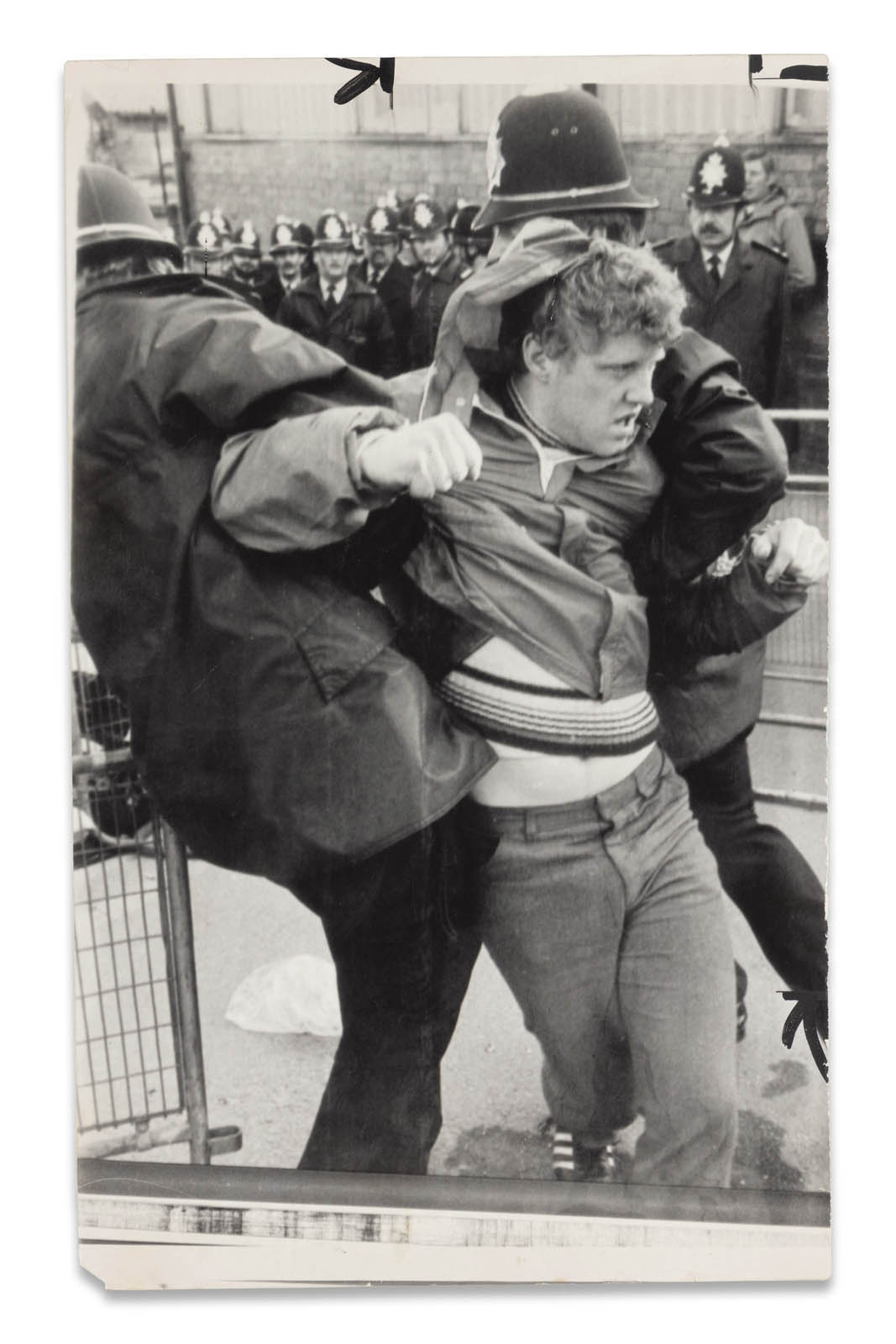

The photographs depict the miners struggle for existence through nuance, context and detail and set out to portray the essence of the mining communities identity under duress. There is a wonderful sense of empathy from the photographers towards the people they are photographing, a warts and all approach documenting their class struggle. But we must also be aware that photographs were used by the government and the media to portray the miners as the villains of the conflict, for photography is situated ‘within the reproduction of certain forms of power that can reorganise, map, and penetrate the body’.7 This power is then used in exploitative and controlling ways… as in when the “BBC reversed footage on the Six O’Clock News to suggest the miners had attacked the police, and that the police had simply retaliated. [Despite an Independent Police Complaints Commission report in 2015 confirming the reversal, the BBC has never officially accepted this.]”8 Other examples of the exploitative use of photographs and biased reporting to denigrate the fight and plight of the miners appeared in the tabloid press with newspapers facing allegations that the coverage of the strike amounted to a “propaganda assault on the miners.”9

Photography and film, then, was used to reorganise the truth, map the conflict on tv and in the media, and penetrate the political and social “body” of the United Kingdom, used by the powers that be in controlling and exploitative ways to demonise the miners’ cause in the eyes of the British public.

Susanna Viljanen perceptively, directly and sadly observes that,

“While technically Thatcher was right – most of the mines were unprofitable, many worked at loss and each tonne of coal produced negative cash flow – the aftermath was sad. Thatcher was not only a crank, she was utterly vindictive. The Unions had brought down Edward Heath’s cabinet 1974, and now the Conservatives extracted revenge on the Unions – and on the British working class. Many of the former mine towns fell into bankruptcy, poverty and despair.

It also turned out that her theory of self-correctiveness of the market economy was simply wrong. New businesses did not emerge and the miners did not get relocated on job markets, but mass unemployment ensued. The aftermath also destroyed the social fabric and the networks of the mining towns and the working class, exacerbating the situation even worse. The destruction wasn’t creative, it was merely destructive.”

While I realise the coal mining industry would have eventually closed with the move to renewables (the United Kingdom has just become the first major country to announce the closure of all coal fired power stations ending its 142-year reliance on the fossil fuel) – there is still a double loss from the British state’s abuse of power and the outcome of the Miners’ Strike, the results of which are still being felt today – namely that Britain lost any form of empathy for the working man, and it lost the history of its working people, its culture and social community.

Men had to move away to find jobs as new industries did not emerge where old ones were closed. Country towns and mining towns were depopulated and became even more impoverished than they were before. Colliery bands and choirs vanished, a sense of community was eviscerated and with the closure of the pits the life energy of the villages was destroyed. Bankruptcy, poverty and despair ensued. A social history that stretched back centuries had been disembowelled, obliterated.

This is the great sadness of those times. This cold, freezing winter of our discontent.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Footnotes

1/ “History of coal miners,” on the Wikipedia website

2/ “Coal mining in the United Kingdom,” on the Wikipedia website

3/ “History of trade unions in the United Kingdom,” on the Wikipedia website

4/ “Arthur Scargill,” on the Wikipedia website

5/ George Monbiot. “Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems,” on The Guardian website 15 April 2016 [Online] Cited 23/09/2024

6/ “Photography has long been associated with acts of resistance. It is used to document action, share ideas, inspire change, tell stories, gather evidence and fight against injustice.”

Text from the exhibition Acts of Resistance: Photography, Feminisms and the Art of Protest, 2024 on the South London Gallery website [Online] Cited 29/09/2024

7/ Michael Hayes. “Photography and the Emergence of the Pacific Cruise: Rethinking the representational crisis in colonial photography,” in Eleanor M. Hight and Gary D. Sampson (eds.,). Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place. Routledge, 2002, pp. 172-87.

8/ Lesley Boulton quoted in Adrian Tempany. “‘A policeman took a full swipe at my head’: Lesley Boulton at the Battle of Orgreave, 1984,” on The Guardian website 17 December 2016 [Online] Cited 23/09/2024

“The miners always said the police had brutally attacked them without justifiable provocation, and that the attack felt preplanned. They complained that the BBC had reversed footage, to show miners who threw missiles seemingly before the police charge rather than in retaliation for it…

Far less publicised, a year later, was the unravelling of the police case. Officers had arrested and charged 95 miners with riot, an offence of collective violence carrying a potential life sentence. Yet in July 1985 the prosecution withdrew and all the miners were were acquitted after the evidence of some police officers, including those in command, had been discredited under cross-examination.

In 1991 South Yorkshire police paid £425,000 compensation to 39 miners who had sued the force for assault, unlawful arrest and malicious prosecution. But still the police did not admit any fault, and not a single police officer was ever disciplined or prosecuted.”

David Conn. “We were fed lies about the violence at Orgreave. Now we need the truth,” on The Guardian website 22nd July 2015 [Online] Cited 03/10/2024

9/ “My recent research, which involved analysis of both news language and press photographs of the time, shows that this year-long strike was portrayed by newspapers – on all sides – as a metaphorical war between the government and the National Union of Mineworkers.

It shows how the media used “war framing” words, phrases and photographs while reporting the strike – often drawing on iconic texts and images associated with World War I. This framing presented the miners as “the enemy”, while at the same time, it justified the actions of the government and the police as necessary and even noble.”

Christopher Hart. “War on the picket line: how the British press made a battle out of the miners’ strike,” on The Conversation website June 8, 2016 [Online] Cited 03/10/2024

“The 1984-1985 miners’ strike was a defining moment in British industrial relations. Shafted, edited by Yorkshire freelance Granville Williams and published by the Campaign for Press and Broadcasting Freedom (CPBF), to which the NUJ is affiliated, has been published to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the start of the strike. It bravely explores the ways in which the media covered the strike and looks into the devastating impact of the pit closure programme on mining communities.

It analyses the pressures on journalists who reported the strike, with accounts from prominent reporters, among them Pete Lazenby of the Yorkshire Evening Post, Nick Jones of the BBC, and Paul Routledge of The Times. But the book also looks at the important contribution from the alternative media and the coverage of the long conflict by freelance photographers and filmmakers.”

Julio Etchart. “Shafted,” on the Freelance website May 2009 [Online] Cited 03/10/2024

10/ Susanna Viljanen. “Why didn’t Thatcher realize the mining towns would become much poorer without the mines?,” on the Quora website Nd [Online] Cited 29/09/2024

Many thankx to Zena Howard for her help, and to the Martin Parr Foundation and Four Corners for allowing me to publish the photographs and art work in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“We face not an employer, but a government aided and abetted by the judiciary, the police and you people in the media.”

Arthur Scargill

“For those who have lived through this strike, its enormity cannot be underestimated. We have brought together some of the best-known photographs – including John Harris’s image of a policeman with a truncheon held from a horse swinging at a cowering woman, and John Sturrock’s photograph of the confrontation between mass pickets and police lines at Bilston Glen – to rarely seen snapshots taken by Philip Winnard, a striking miner himself.”

Martin Parr

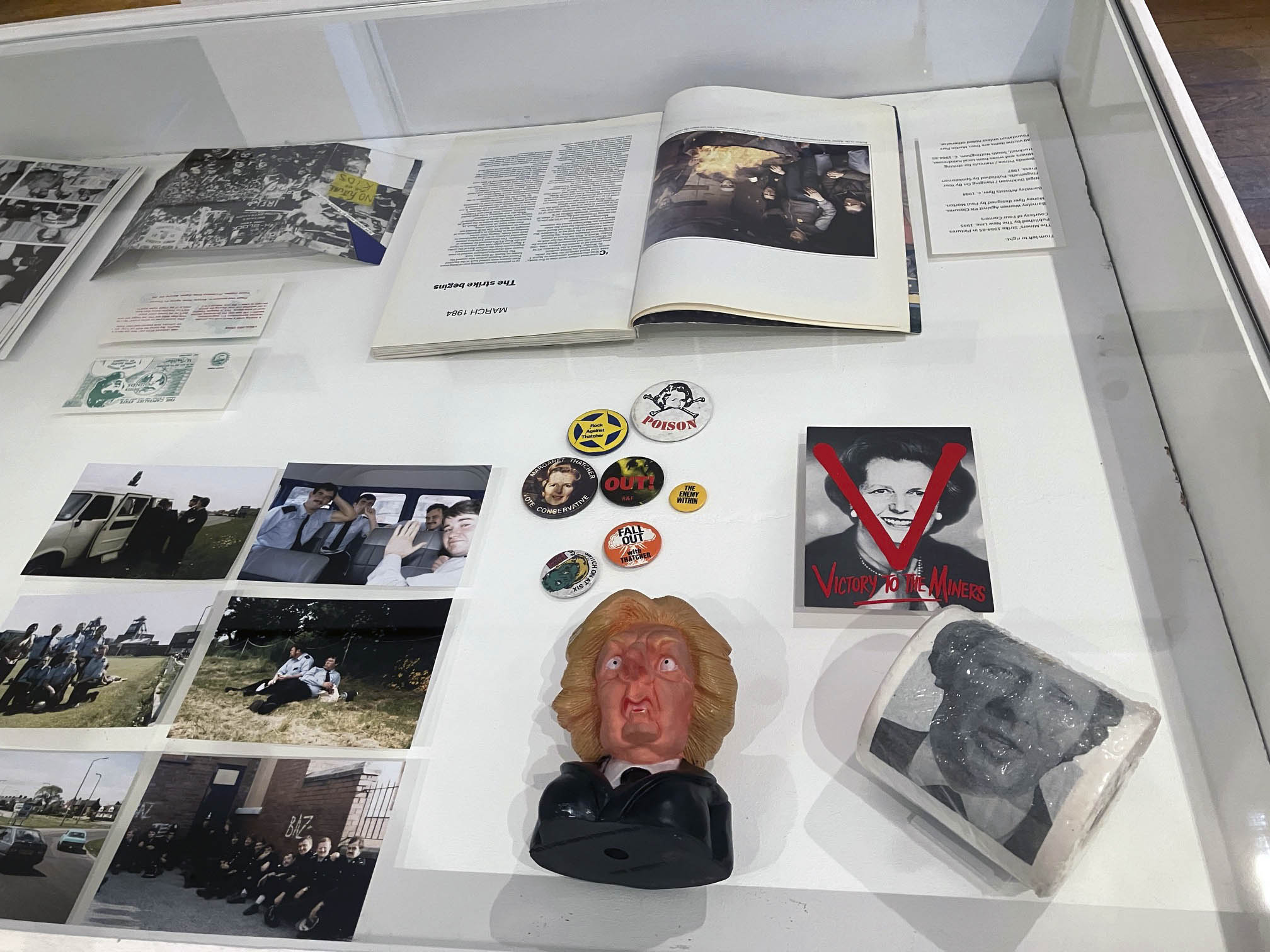

“The exhibition is an attempt to commemorate and reflect on the miners’ strike of 1984-85, a seismic, yet often overlooked event in the recent history of Britain. By focusing on the complex role photographs played during the year-long struggle we hope for the show to transcend the purely historical or nostalgic and take the visitor on a journey through a series of timeless images that show the resilience, camaraderie and violence of the strike, to reconnect and consider it again in relation to the present. The ephemera materials show the urgent use of images and the creativity that was deployed in support of the striking miners. Together, the works tell a story of the battle against Margaret Thatcher and the National Coal Board’s pit closures, but what ultimately shines through is the unity and imagination of people coming together in defence of their communities and the basic rights to work and to survive.”

Isaac Blease, Exhibition Curator

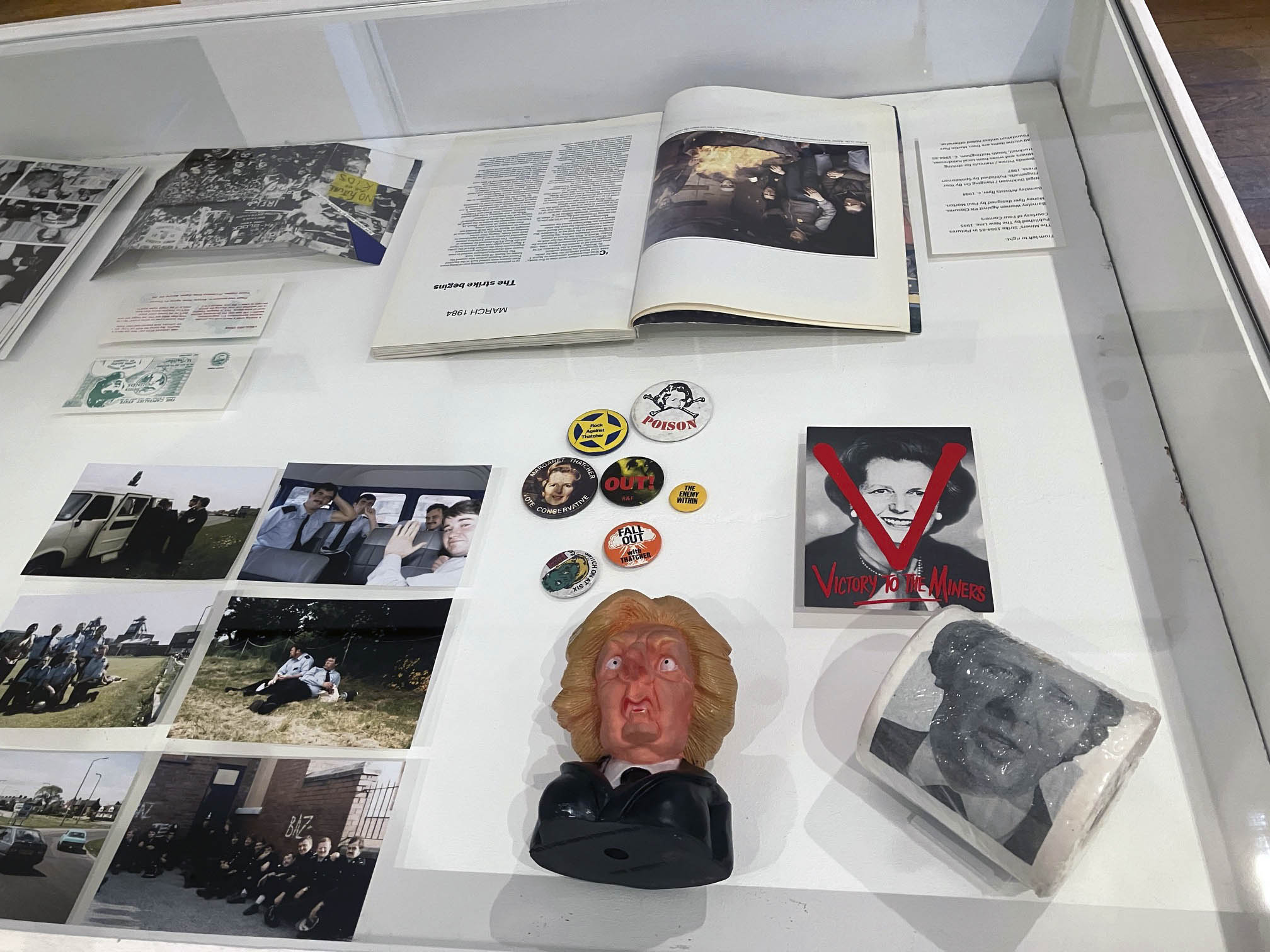

ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 explores the vital role that photography played during this bitter industrial dispute. To commemorate the 40th anniversary of the miners’ strike, Four Corners is delighted to tour this exhibition from the Martin Parr Foundation. One of Britain’s longest and most violent disputes, the repercussions of the miners’ strike continue to be felt today across the country.

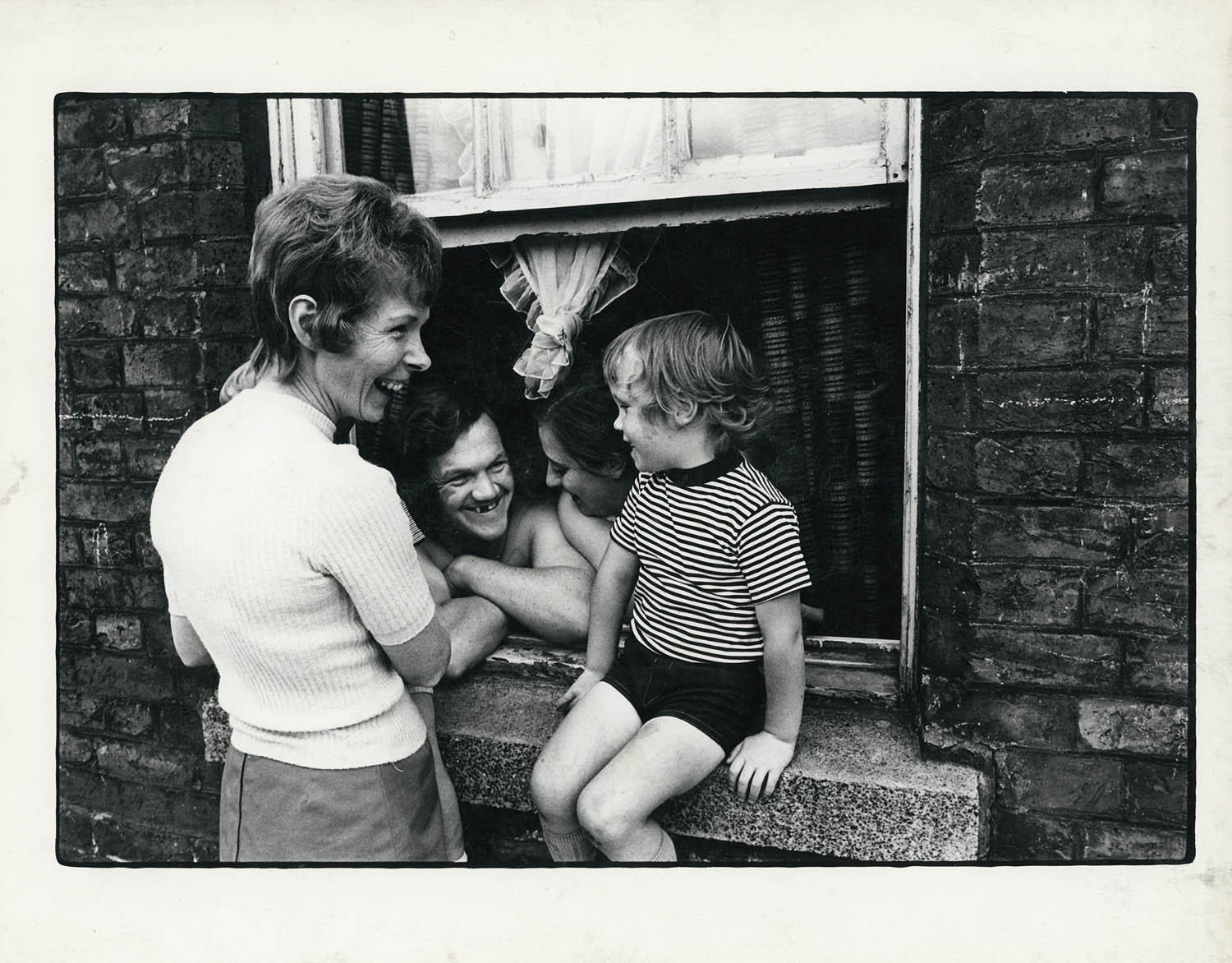

The exhibition looks at the central role photographs played during the year-long struggle against pit closures, with many materials drawn from the Martin Parr Foundation collection. Posters, vinyl records, plates, badges and publications are placed in dialogue with images by photographers, investigating the power and the contradictions inherent in using photography as a tool of resistance. They include photographs by Brenda Prince, John Sturrock, John Harris, Jenny Matthews, Roger Tiley, Imogen Young and Chris Killip, as well as Philip Winnard who was himself a striking miner.

The photographs show some familiar imagery – the lines of police and the violence – but also depict the remarkable community support from groups such as Women Against Pit Closures and the Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners. Photography was used both to sway public opinion and to document this transformative period in British history.

The catalyst for the miners’ strike was an attempt to prevent colliery closures through industrial action in 1984-85. The industrial action, which began in Yorkshire, was led by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and its President, Arthur Scargill, against the National Coal Board (NCB). The Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher opposed the strikes and aimed to reduce the power of the trade unions. The dispute was characterised by violence between the flying pickets and the police, most notably at the Battle of Orgreave. The miners’ strike was the largest since the General Strike of 1926 and ended in victory for the government with the closure of a majority of the UK’s collieries.

Text from the Four Corners website

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency. It maintains that “the market” delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning.

Attempts to limit competition are treated as inimical to liberty. Tax and regulation should be minimised, public services should be privatised. The organisation of labour and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for utility and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone. Efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive. The market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve.

George Monbiot. “Neoliberalism – the ideology at the root of all our problems,” on The Guardian website 15 April 2016 [Online] Cited 23/09/2024

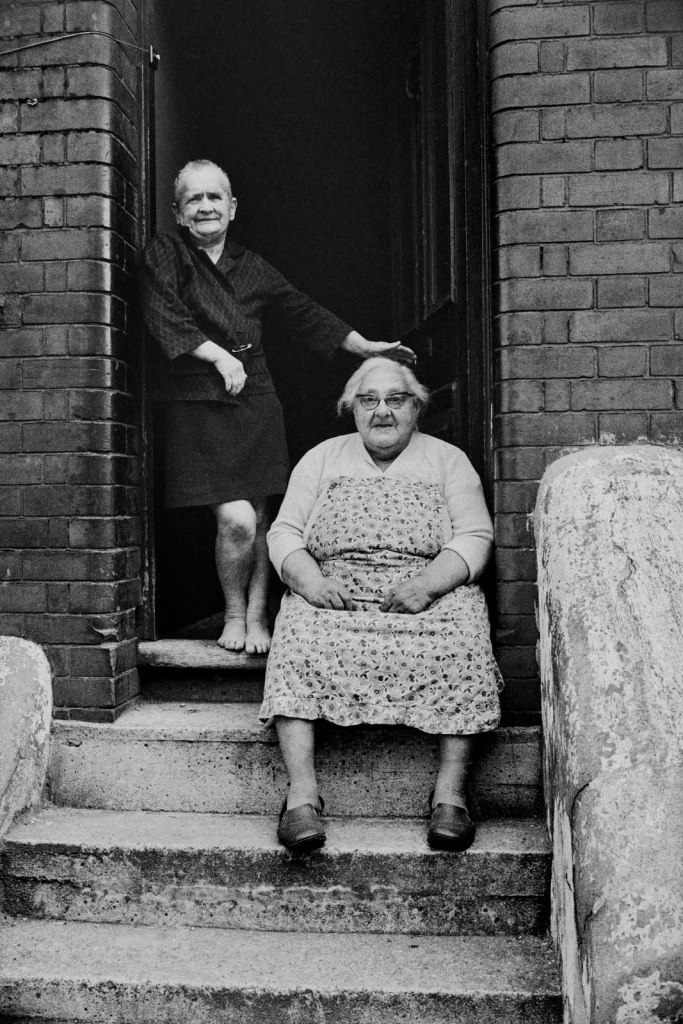

Bill Brandt (British, born Germany 1904-1983)

Unemployed miner returning home from Jarrow

1937

Gelatin silver print

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Installation view of the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 at Four Corners, London showing:

At top left

Unknown maker (British)

Dartboard with Margaret Thatcher photograph

Nd

Martin Parr Foundation Collection

At left,

John Sturrock (British)

In the wake of an earthmoving machine, men search for small lumps of coal on an old colliery tip at South Kirby

13th December, 1984

At second left,

Unknown maker (British)

When They Close A Pit They Kill A Community

Welsh Congress in Support of Mining Communities 1984-1985

1985

Poster

Bill Brandt (British, born Germany 1904-1983)

Coal-Miner’s Bath, Chester-le-Street, Durham

1937

Gelatin silver print

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

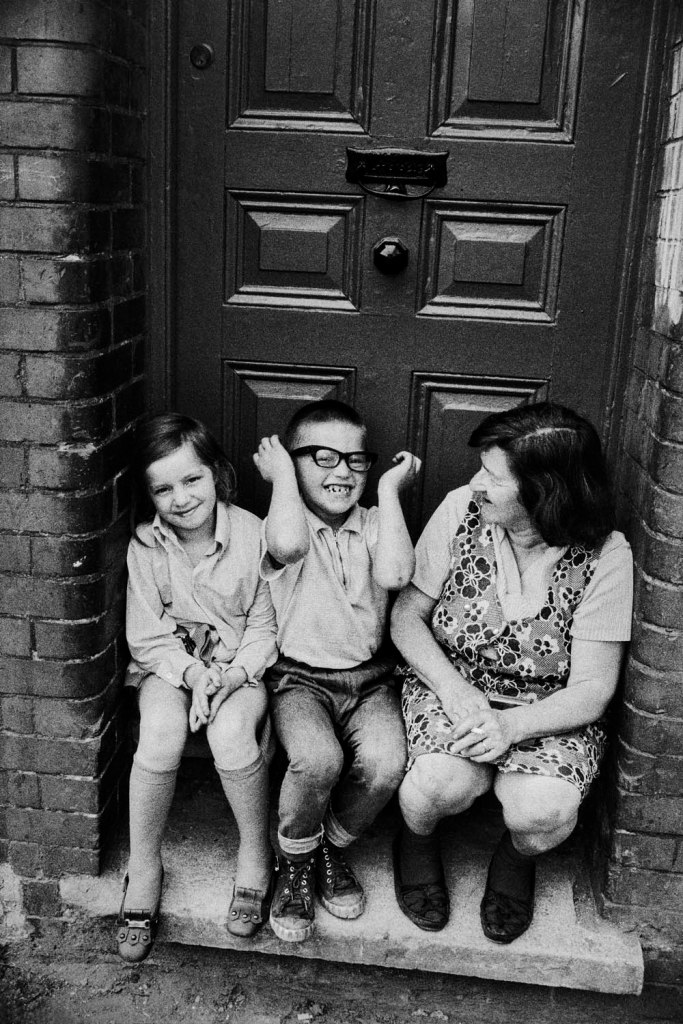

Brenda Prince (British, b. 1950)

Dot Hickling on strike from N.C.B canteen at Linby Colliery helped organise and turn the miners kitchen in Hucknall for a year during strike. Son & son-in-law also on strike, Nottingham

1984/85

© Brenda Prince

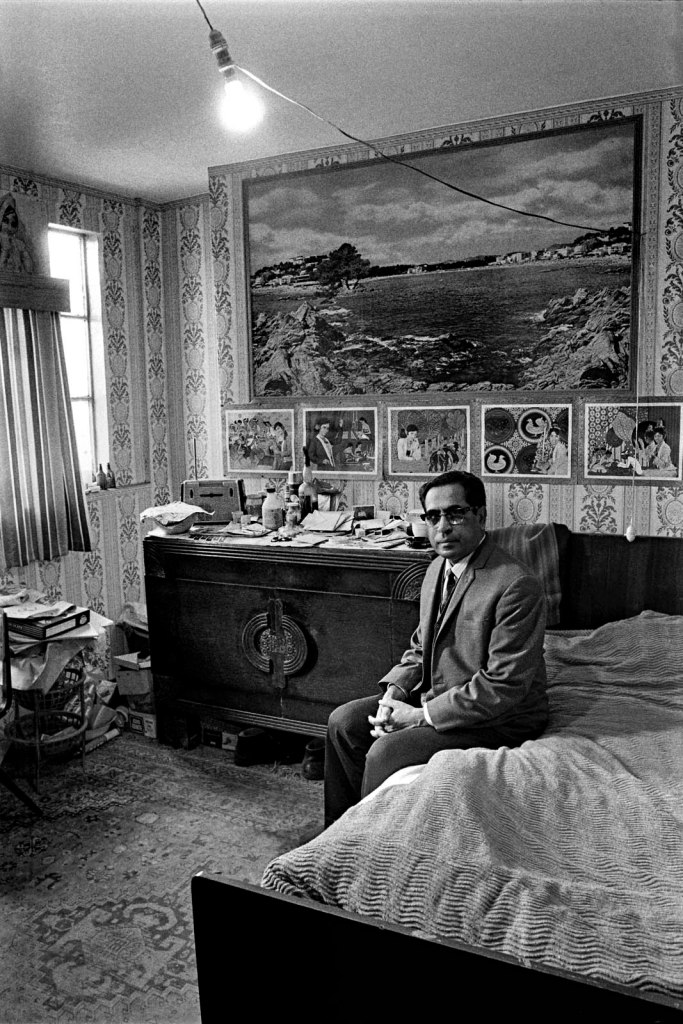

Bill Brandt (British born Germany, 1904-1983)

Northumbrian Miner at His Evening Meal

1937

Gelatin silver print

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

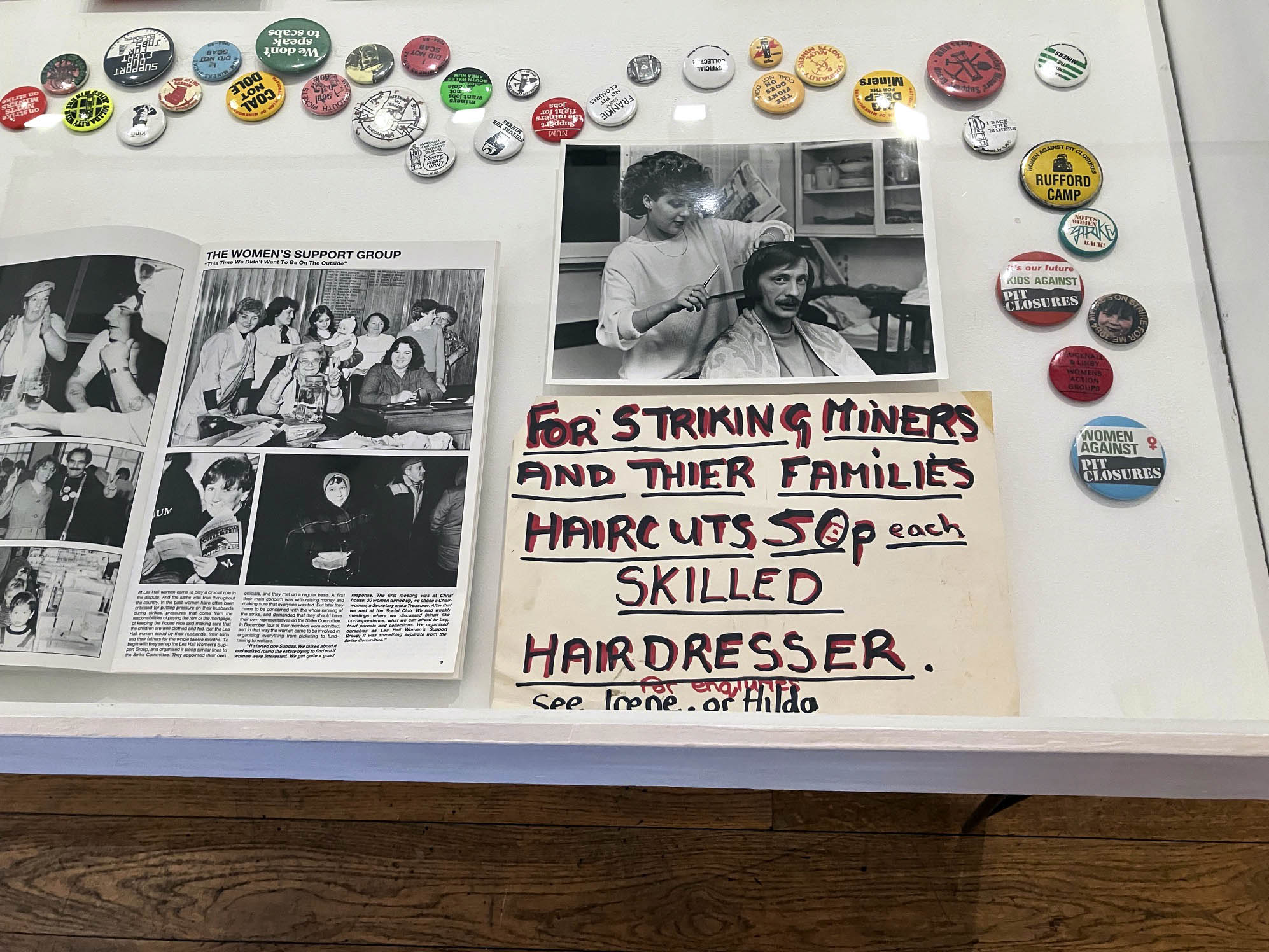

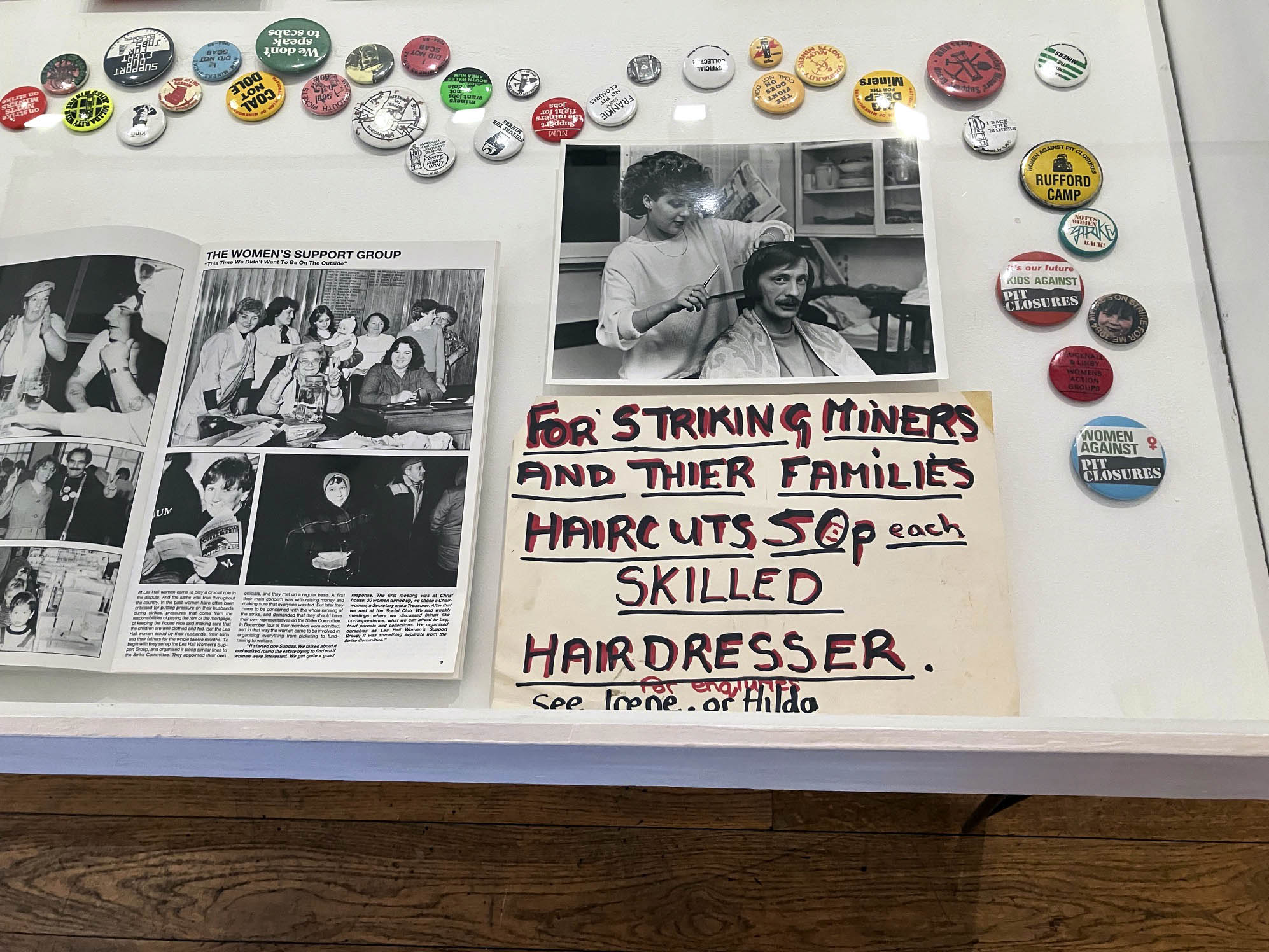

Installation view of the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 at Four Corners, London showing below the text from the magazine at left:

The Women’s Support Group

“This Time We Didn’t Want To Be On The Outside”

At Lea Hall women came to play a crucial role in the dispute. And the same was true throughout the country. In the past women have often been criticised for putting pressure on their husbands during strikes, pressures that come from the responsibilities of paying the rent or the mortgage, of keeping the house nice and making sure that the children are well clothed and fed. But the Lea Hall women stood by their husbands, their sons and their fathers for the whole twelve months. To being with they set up the Lea Hall Women’s support Group, and organised it along similar lines to the Strike Committee. They appointed their own officials, and they met on a regular basis. At first their main concern was with raising money and making sure that everyone was fed. But later they came to be concerned with the whole running of the strike, and demanded that they should have their own representatives on the Strike Committee. In December four of their members were admitted, and in that way the women came to be unbolted in organising everything from picketing to fundraising to welfare.

“It started one Sunday. We talked about it and walked around the estate trying to find out if women were interested. We got quite a good response. The first meeting was at Chris’ house, 30 women turned up, we chose a Chairwoman, a Secretary and a Treasurer. After that we met at the Social Club. We had weekly meetings where we discussed things like correspondence, what we can afford to buy, food parcels and collections. We organised ourselves as Lea Hall Women’s Support Group; it was something separate from the Strike Committee.”

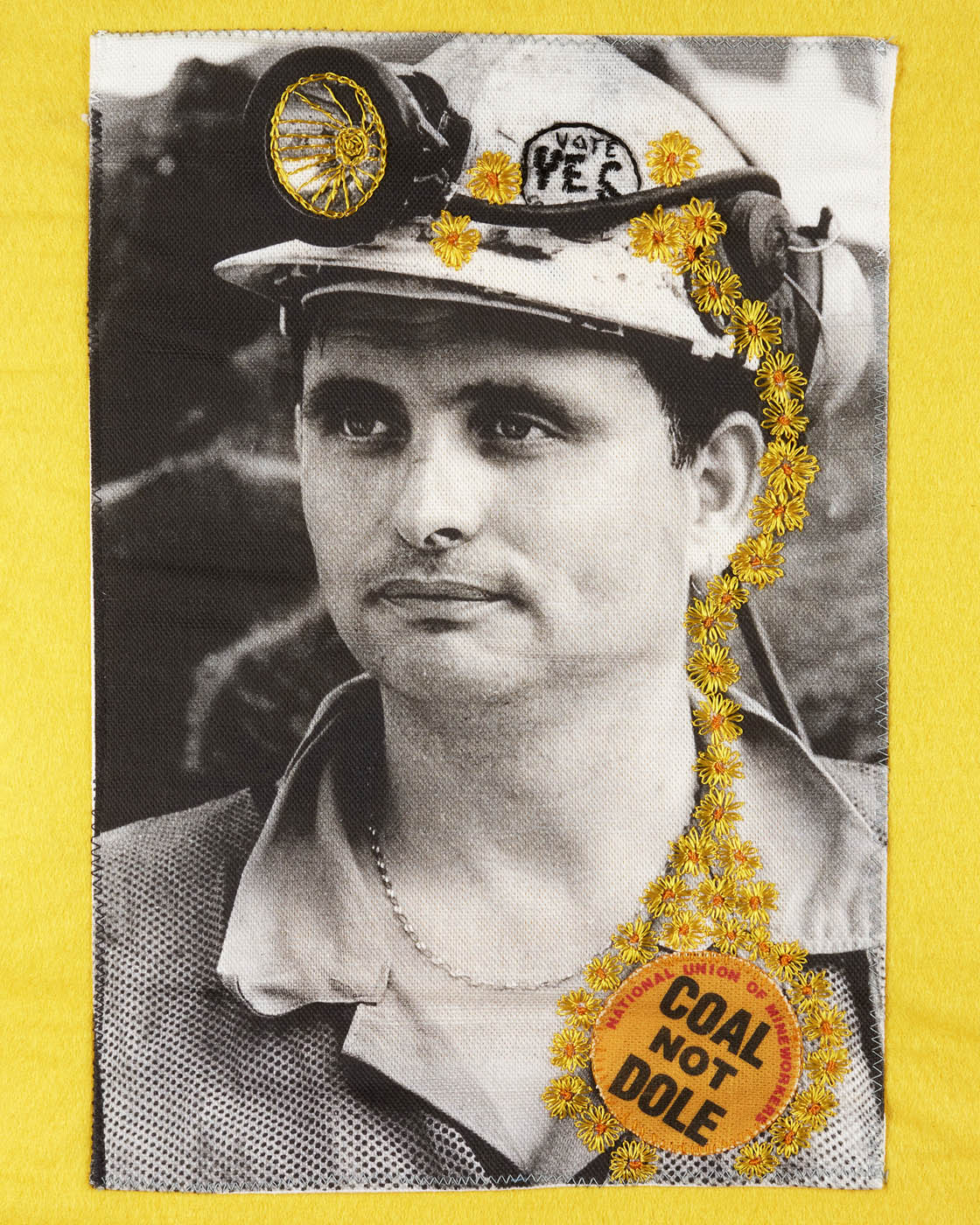

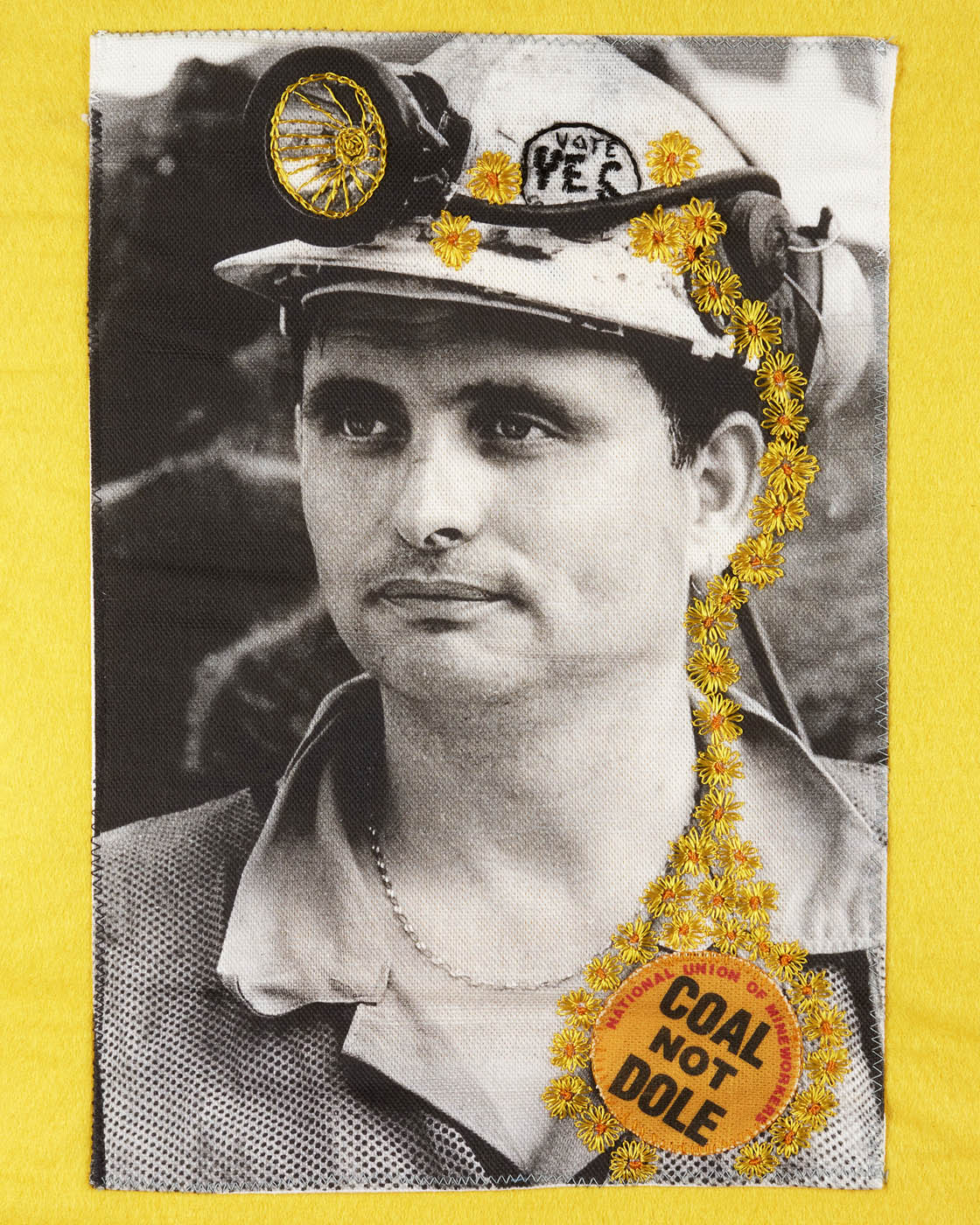

Installation view of the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 at Four Corners, London showing at left, Jenny Matthews’ quilt commissioned by the Martin Parr Foundation to mark the 40th anniversary of the miners’ strike

Jenny Matthews (British)

Cole Not Dole

Nd

© Jenny Matthews

Detail from a quilt commissioned by the Martin Parr Foundation to mark the 40th anniversary of the miners’ strike.

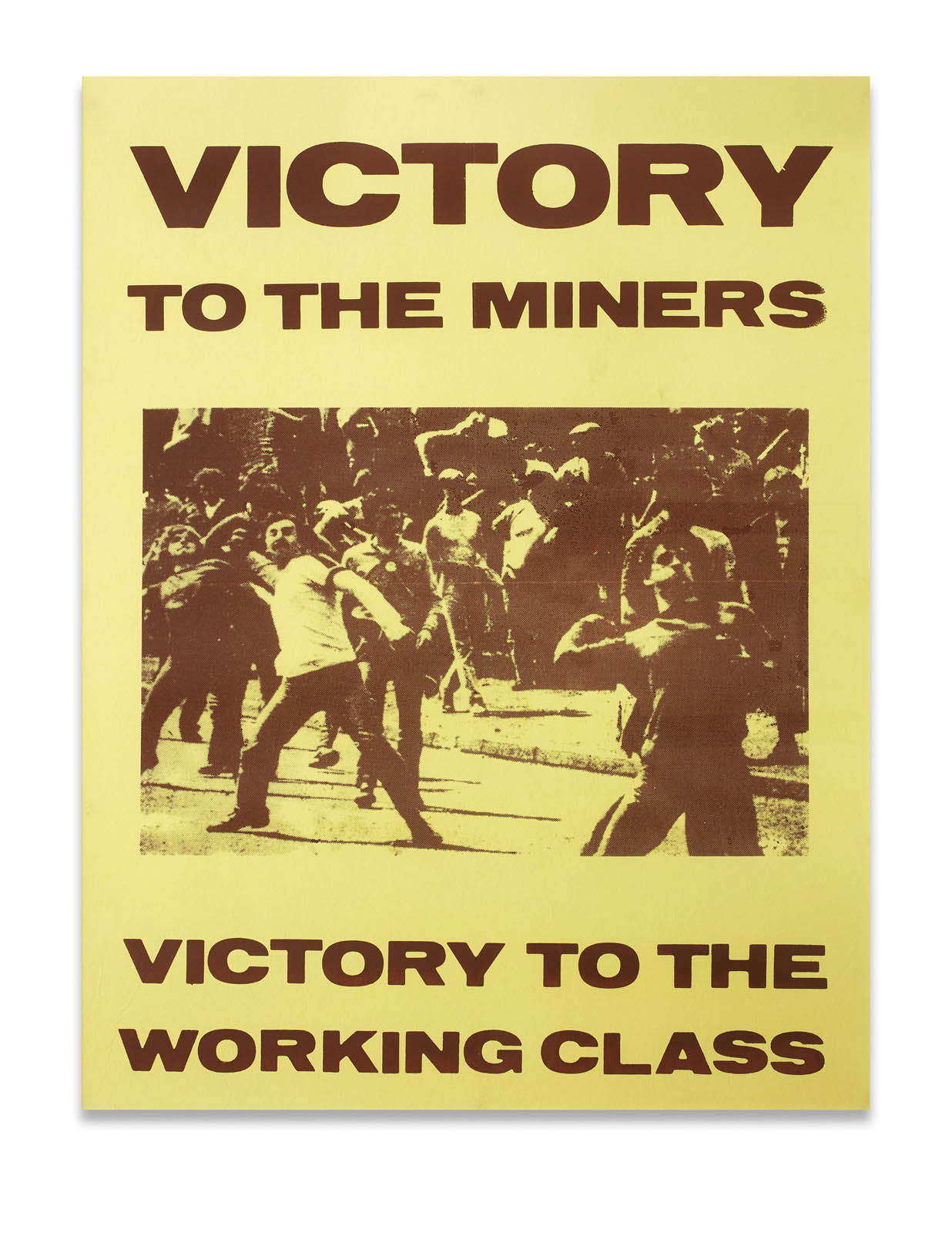

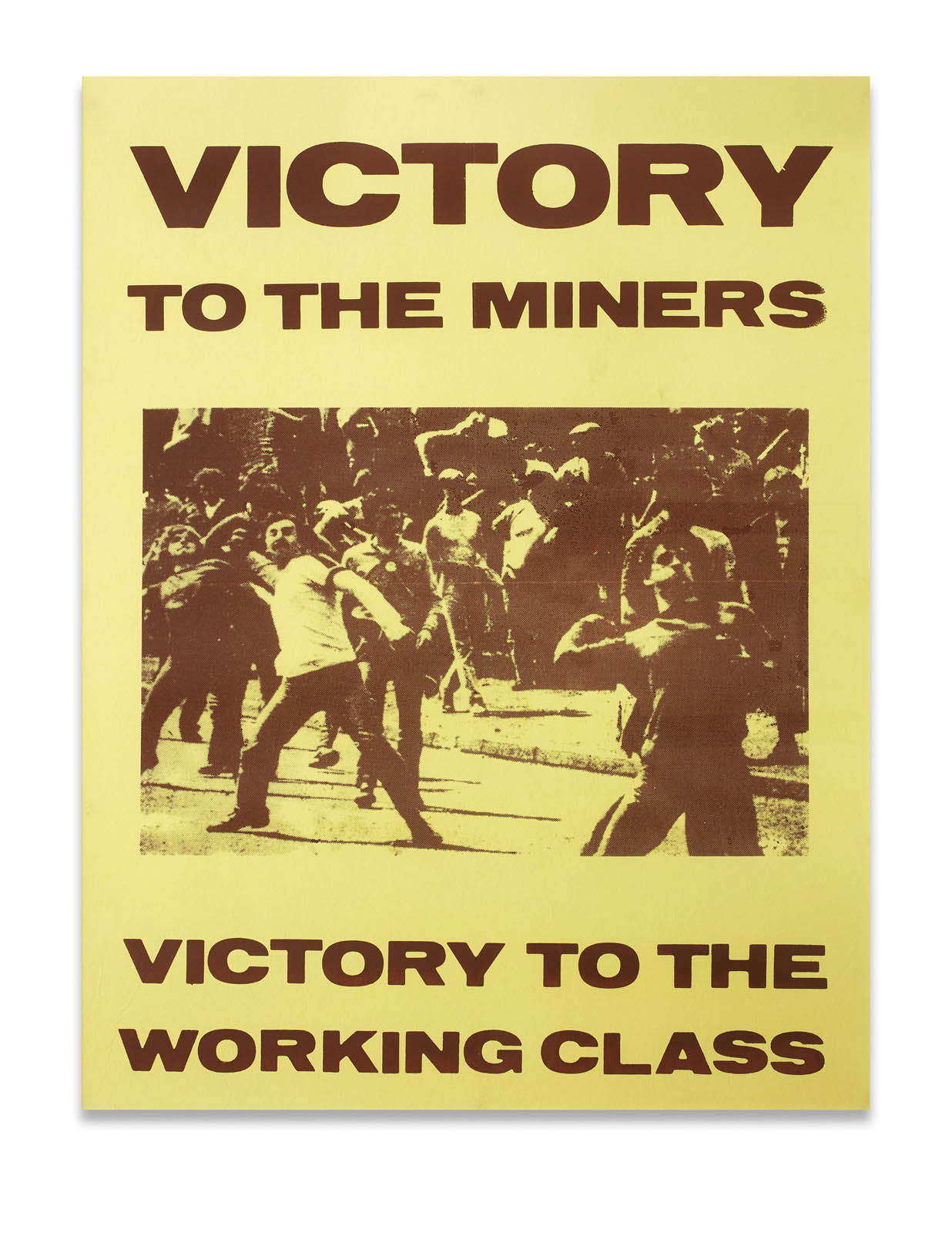

Installation view of the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 at Four Corners, London showing at left the wall text below; in the four photographs from top left clockwise, John Sturrock’s Miners’ Strike 1984 mass picket confronting police lines, Bilston Glen. Norman Strike at the front of a mass picket, Scotland, unknown photographer Carcroft NCB Central Store 1984, Howard Sooley’s Rossington Main Colliery 1984, Roger Tiley’s ‘Scabs’ returning to work, Newbridge, South Wales, 1984-1985; and at right, the poster VICTORY TO THE MINERS, VICTORY TO THE WORKING CLASS (below)

To mark the 40th anniversary of the 1984-85 miners’ strike, Four Corners is delighted to present this exhibition from the Martin Parr Foundation, which looks at the vital role that photographs played during the year-long struggle against pit closures.

The miners’ strike was one of Britain’s longest and most bitter industrial disputes, the repercussions of which continue to be felt throughout the country today. This industrial action was led by the National Union of Mineworkers and its president, Arthur Scargill, against planned colliery closures by the National Coal Board which threatened 20,000 job losses.

Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government strongly opposed the strike and aimed to reduce the power of the trade unions. It was a dispute characterised by weaponised news coverage and visual media created sway public opinion against the strike. Photographs documenting the events in 1984-85 are exhibited here in dialogue with selected ephemera created in support of the miners – including posters, vinyl records, plates, badges and publications.

The exhibited works cover a variety of approaches, from photo-journalism to photo-montage, as well as vernacular photographs taken by Philip Winnard, himself a striking miner. They include some iconic imagery of the lines of police and picket violence – most notably at the infamous Battle of Orgreave. But they also depict the remarkable community solidarity from groups including Women Against Pit Closures and Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners.

The strike ended in defeat for the miners on the 3rd March 1985, with most of Britain’s coal mines shut down. It was a running point in British society, leading to weakened trade unions and loss of workers’ rights, the privatisation of nationalised industries, and today’s insecure jobs market. Forty yeas on, ex-mining communities face a legacy of mass unemployment and social inequality. This exhibition offers a unique account of the strike, but also a space to reflect on power, community and the relationship between photography and societal change.

The exhibition features work by John Harris, Chris Fillip, Jenny Matthews, Brenda Prince, Neville Pyne, Howard Sooley, John Sturrock, Roger Tiley, Philip Winnard, Imogen Young and uncredited photographers of original press prints. It includes many materials drawn from the Martin Parr Foundation collection. The original exhibition was curated by Isaac Blease at Martin Parr Foundation. A book to accompany the exhibition is published by Bluecoat Press.

This exhibition is made possible with the generous support of Alex Sainsbury, Foyle Foundation, Hallett Independent, National union of Mineworkers and the Society for the Study of Labour History. With many thanks to the Martin Parr Foundation, Mary Halpenny-Killip, Matthew Fillip, Ceri Thompson, National Museum of Wales, Craig Oldham, Graham Smith, Bluecoat Press, British Journal of Photography, Isaac Blease, Tom Booth Woodger, Mick Moore and Safia Mirzai.

Wall text from the exhibition

Unknown maker (British)

VICTORY TO THE MINERS, VICTORY TO THE WORKING CLASS

Nd

Poster

Installation view of the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 at Four Corners, London showing closed colliery commemorative plates:

Commemorative Plates

Left, top to bottom

Clayton West NUM Yorkshire Area

The Dirty Thirty No Surrender

Durham Miners Association

Right, top to bottom

Justice for Mineworkers

Littleton Miners’ 1984 Struggle 1985

Loyal to the Last Ollerton Miners

Unknown maker (British)

ACKTON HALL COLLIERY commemorative plate

1985

A series of commemorative plates was made for closed collieries. As shaft sinking began in 1873 the year 1877 may indicate when coal production began.

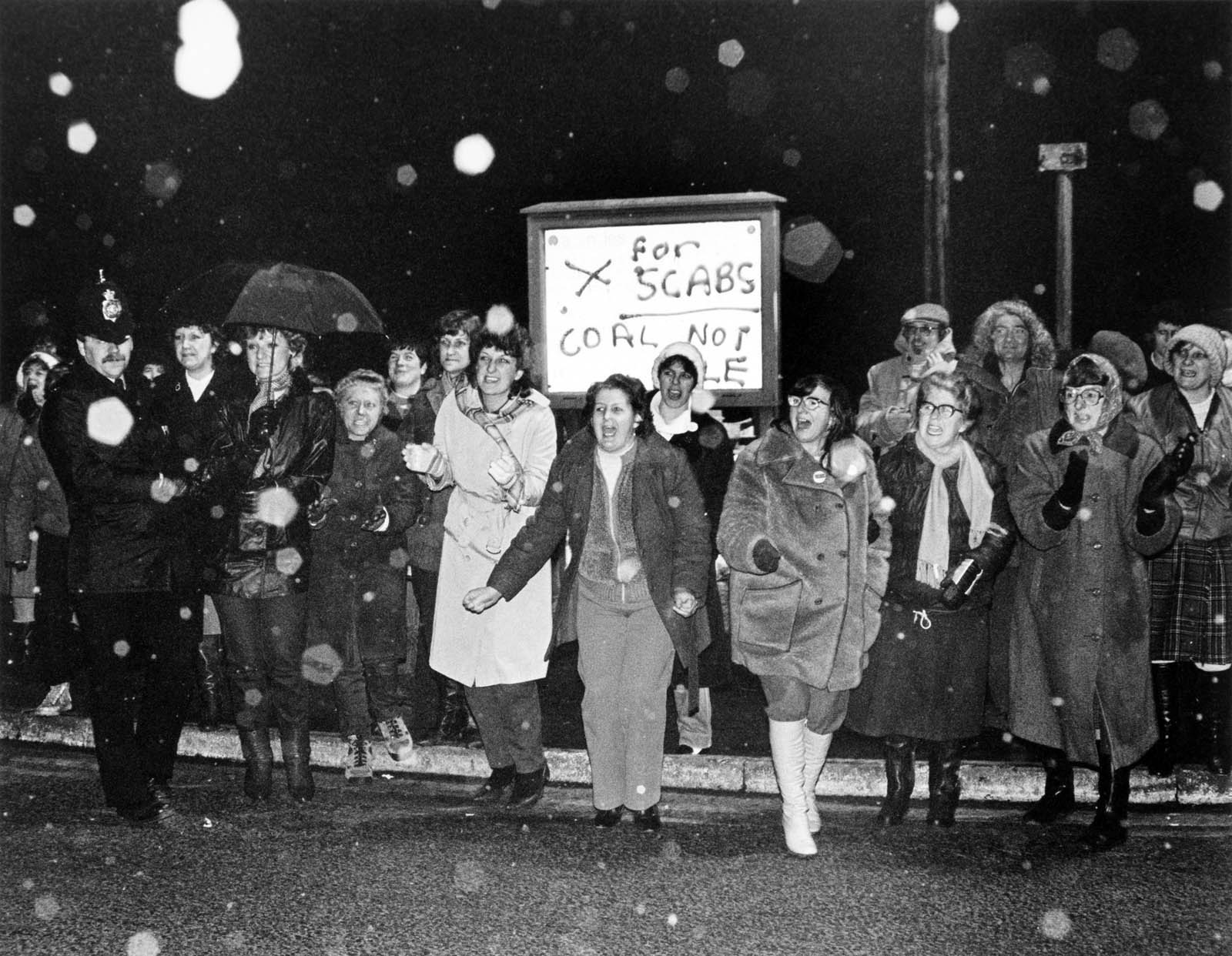

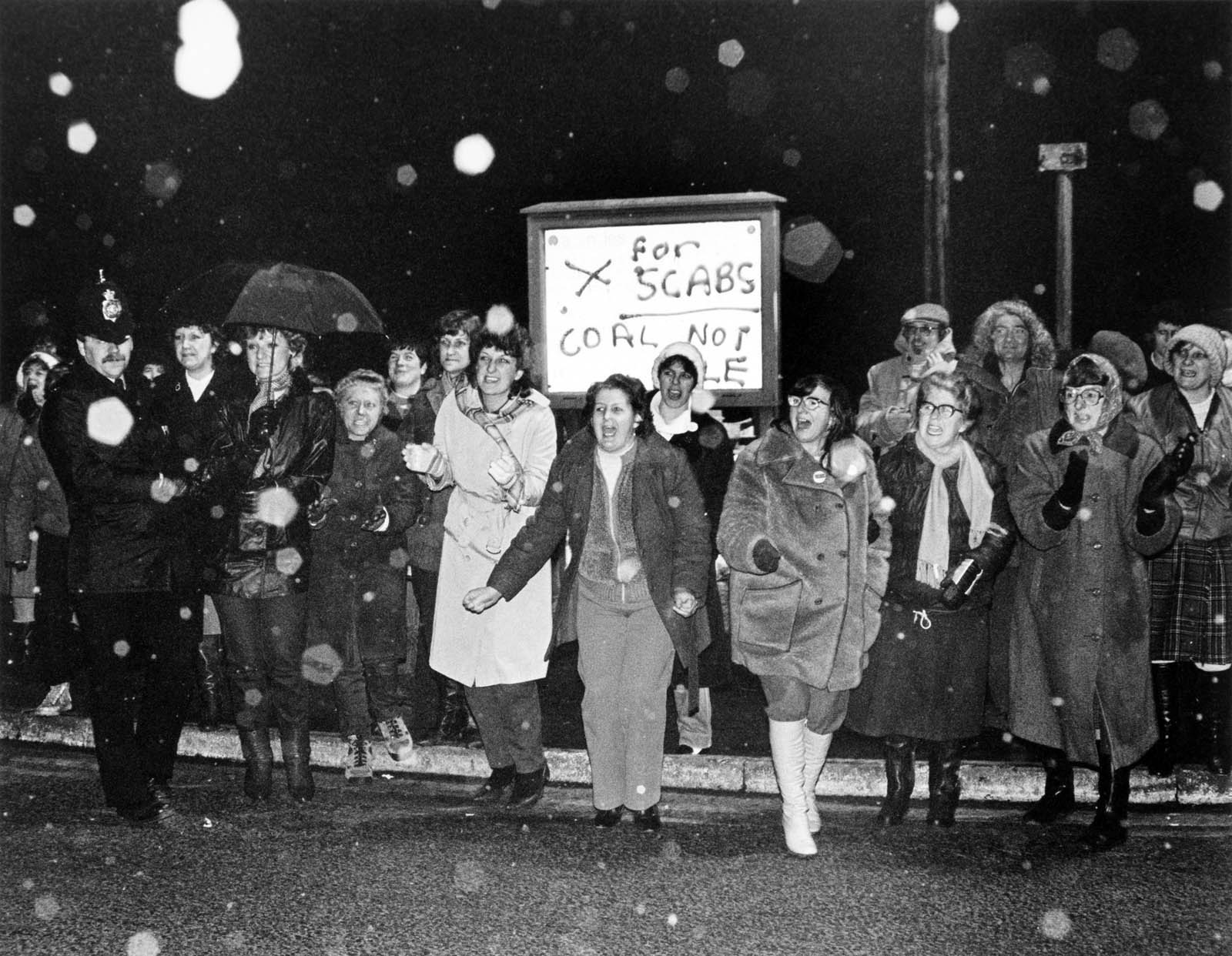

Installation view of the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 at Four Corners, London showing at second left in the bottom image, Brenda Prince’s photograph Women’s’ picket at Bevercotes Colliery, night shift, 11pm. Nottingham, February 1985 (below); and at third right top, Roger Tiley’s photograph NUM union officials, Maerdy Miners’ Hall, Rhondda Fach, South Wales, 1984-1985

Brenda Prince (British, b. 1950)

Women’s’ picket at Bevercotes Colliery, night shift, 11pm. Nottingham

February 1985

Gelatin silver print

© Brenda Prince

We were all documentary photographers who had our own

projects and interests. We would work on our own stories and

my miners’ strike images came out of that. As a working class

woman, I became aware of the inequalities in society; not just

between men and women but also relating to race, class,

people with disabilities and sexuality. The miners’ strike gave

me the opportunity to document working class people who were

really struggling to keep their jobs and keep their communities

alive.

…on starting to document the miners’ strike

My brother lived in Calverton, a small pit village so I was able to

stay with him. I got in touch with Women’s action groups in the

area (Hucknall & Linby, Ollerton) and they put me in touch with

others (Clipstone, Blidworth). I began by photographing the

striking miners’ communal kitchens or soup kitchens and they

gradually got to know me. I was accepted by the men because

they knew I was on their side and perhaps because I was a

woman, they didn’t take me seriously as a ‘Press’

photographer. The more I went up there the more I got to know

people. They’d say, ‘oh you should come with us to so and so’.

I think that’s how I heard about the night pickets at Blidworth.

…on covering the role played by women in the miners’

strike:

There was so much the women were doing. What I found

important about the miners’ strike and women getting involved,

is that up till then many hadn’t taken so much interest in what

was happening in this country politically, but the strike

politicised them – they began to take note and watch the news

and realise that a lot of politicians are hypocrites, and you can’t

trust them and you still can’t.

Women became more confident as a result of the strike, which I

thought was great. It was good for other women and young girls

to see their Mums and daughters speaking out at the meetings,

doing things they wouldn’t have done before, eg. picketing.

Most of them would have been typical mothers and wives,

cleaning, cooking, shopping, looking after their children instead

of going on the picket line, visiting and supporting other

collieries, getting together with other women and planning days

of action, e.g., Women Against Pit Closures.

After the strike, as told to me and recorded in interviews about

the strike, they saw things differently, so it was a positive

experience for some women despite the hardship but hard for

the men who lost their jobs.

Extract from ONE YEAR interview with Brenda Prince on the Martin Parr Foundation website [Online] Cited 24/09/2024

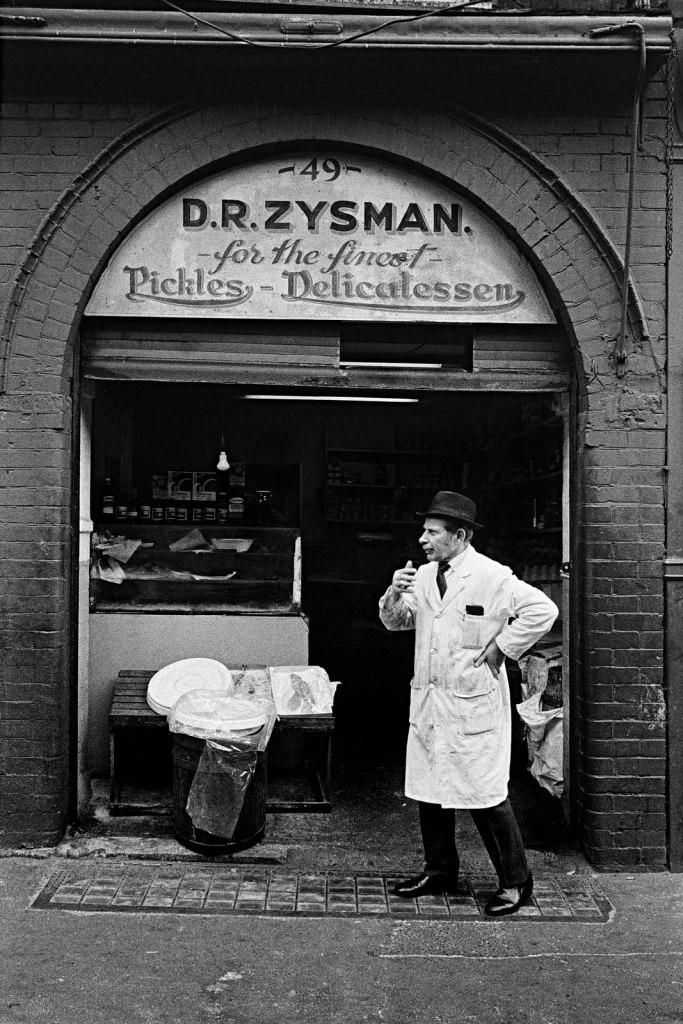

Philip Winnard (British)

Houghton Main

1984

© Philip Winnard

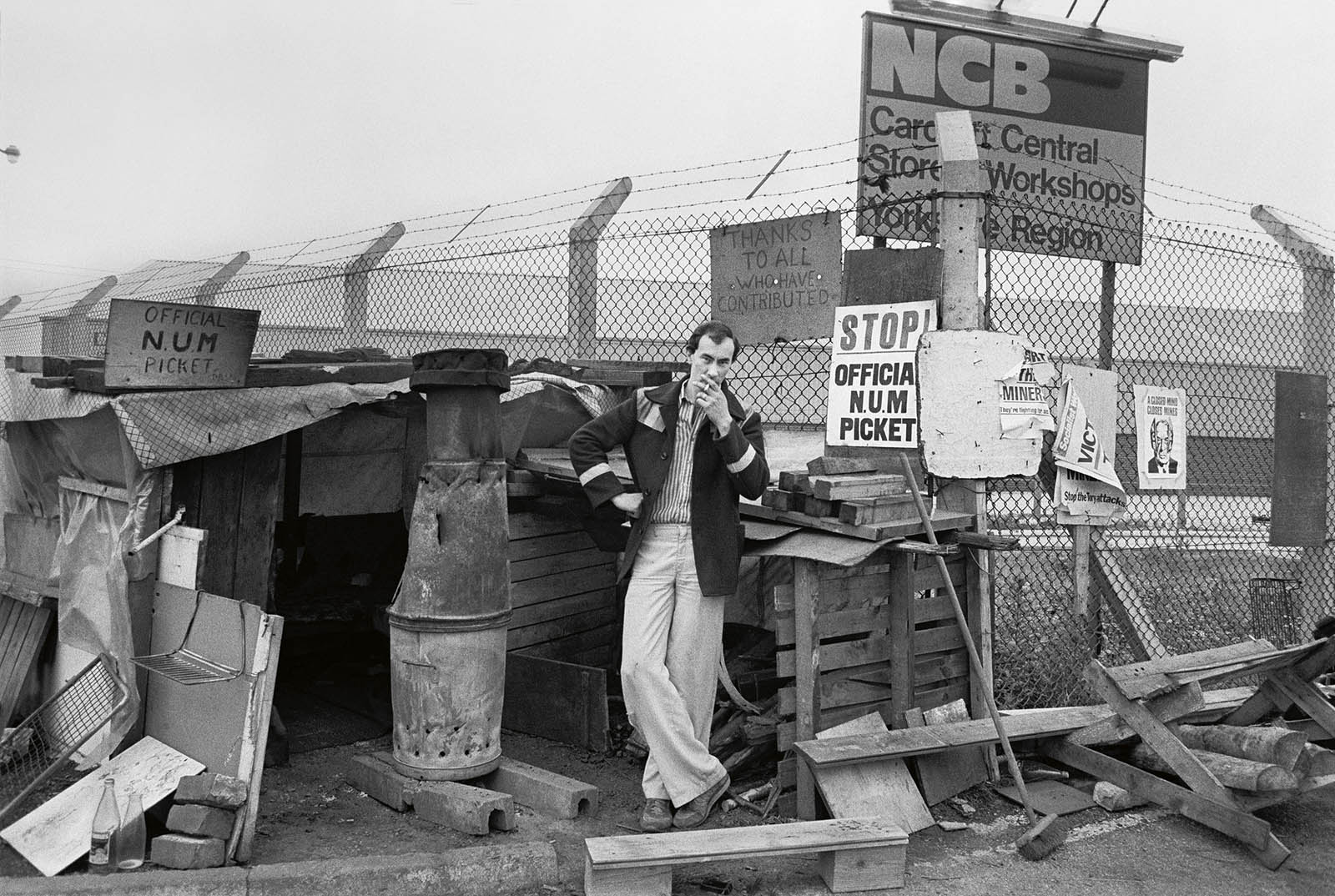

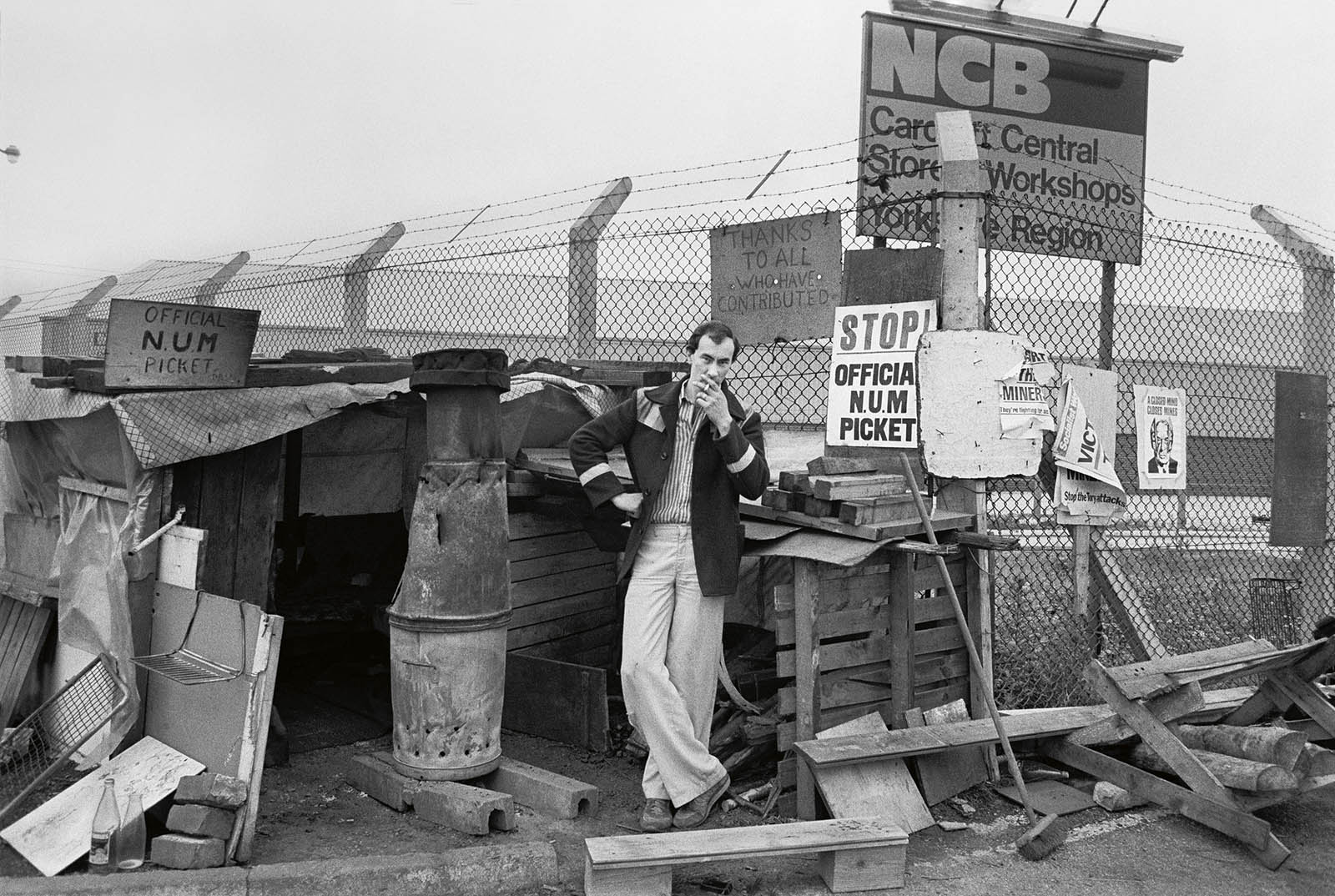

Howard Sooley (British)

Carcroft NCB Central Store

1984

© Howard Sooley

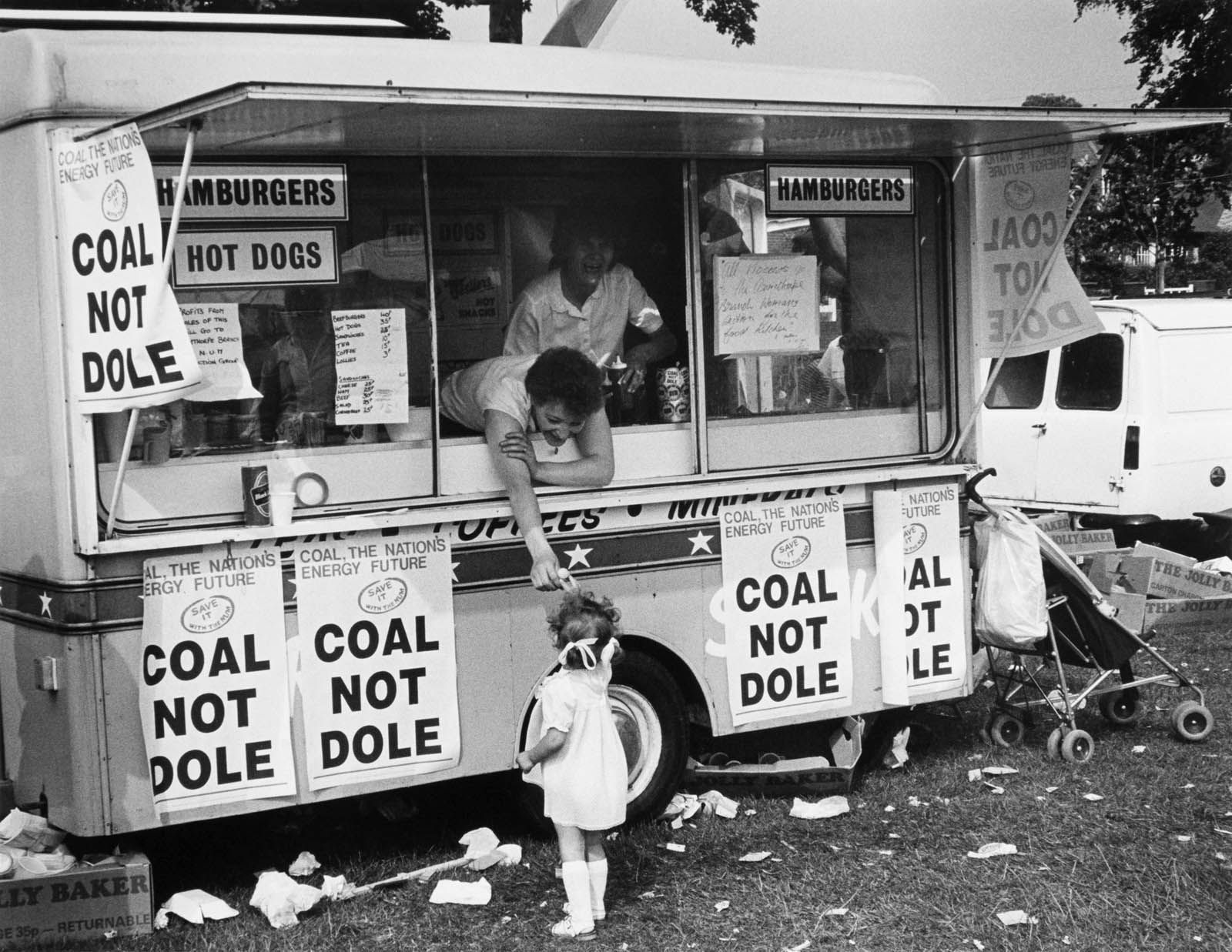

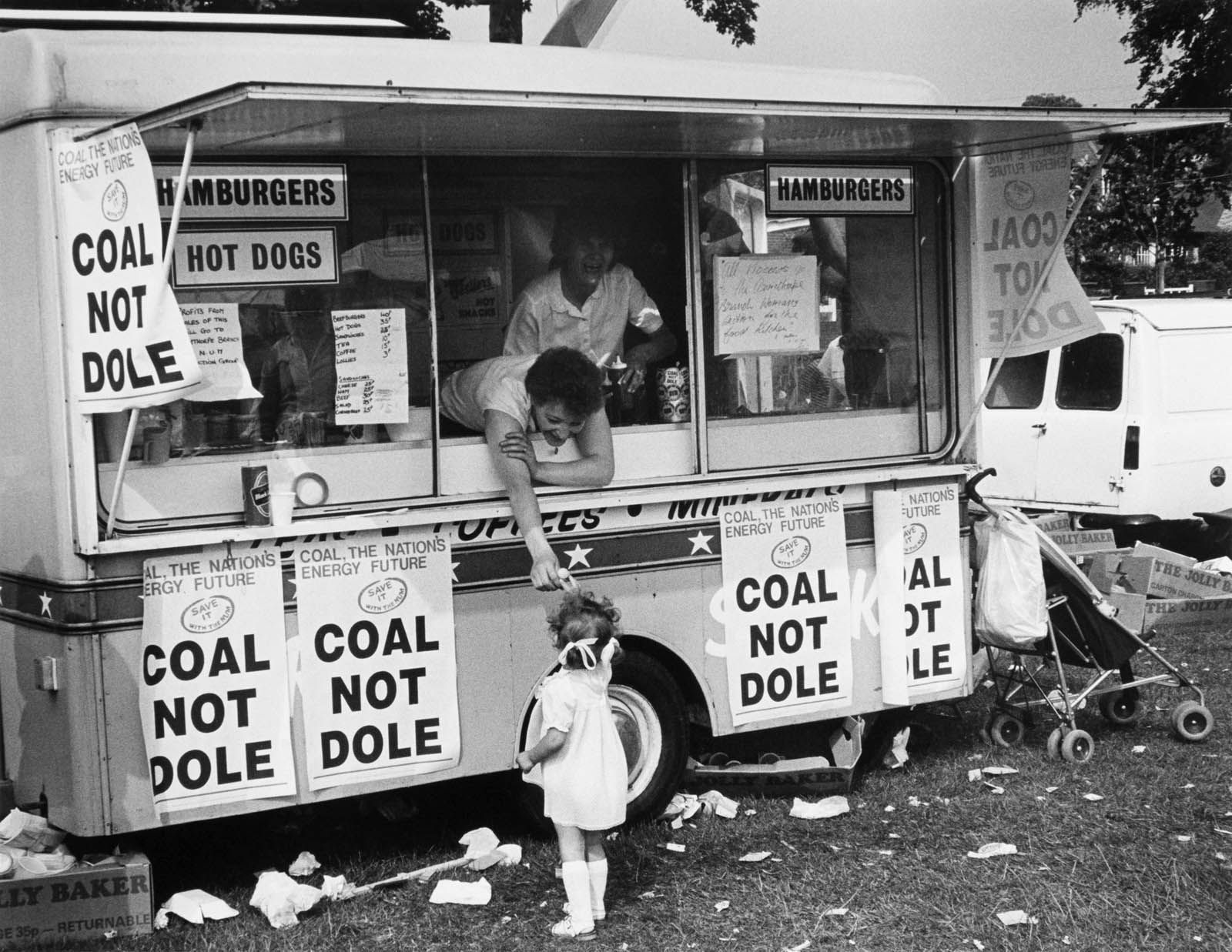

Brenda Prince (British, b. 1950)

Buying an ice cream at Yorkshire Miners’ Gala. June

1984

© Brenda Prince

Photographer uncredited

Three coaches used to take miners to Hem Heath Colliery, burning fiercely at a depot at Trentham near Stoke-on-Trent

1984

Press print

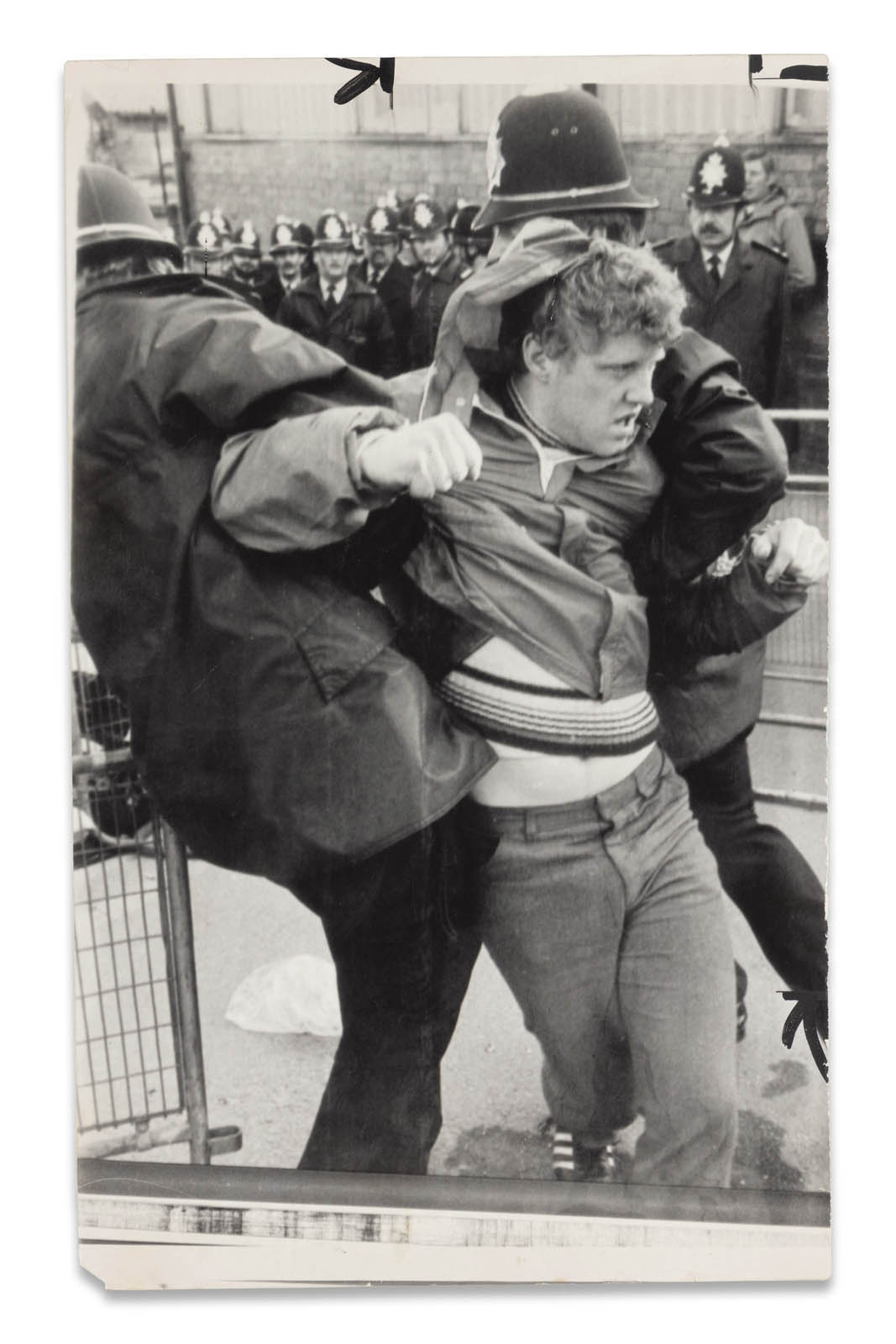

Neville Pyne (British)

A policeman getting to grips with a picket

1984

Press print

© Neville Pyne

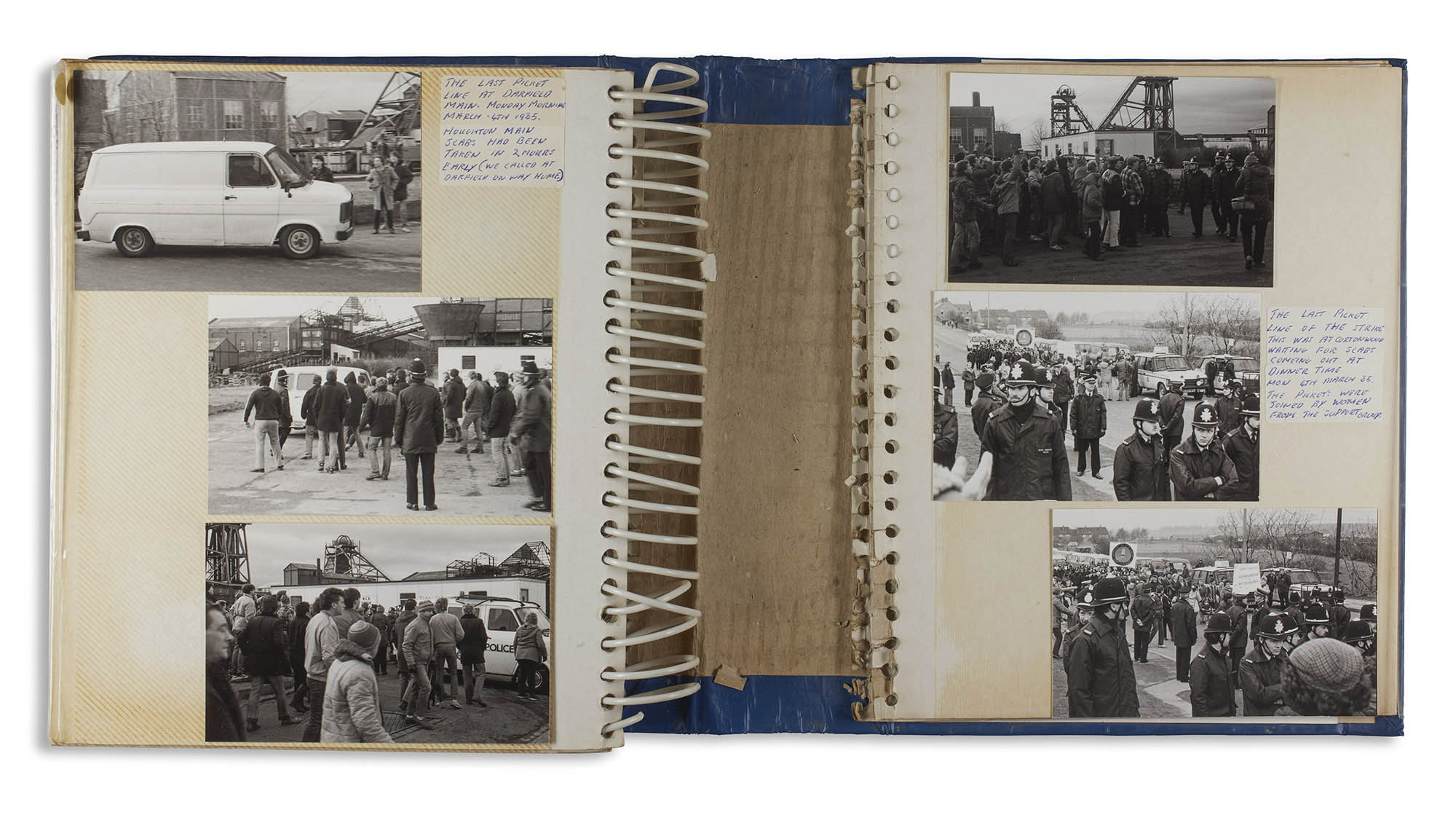

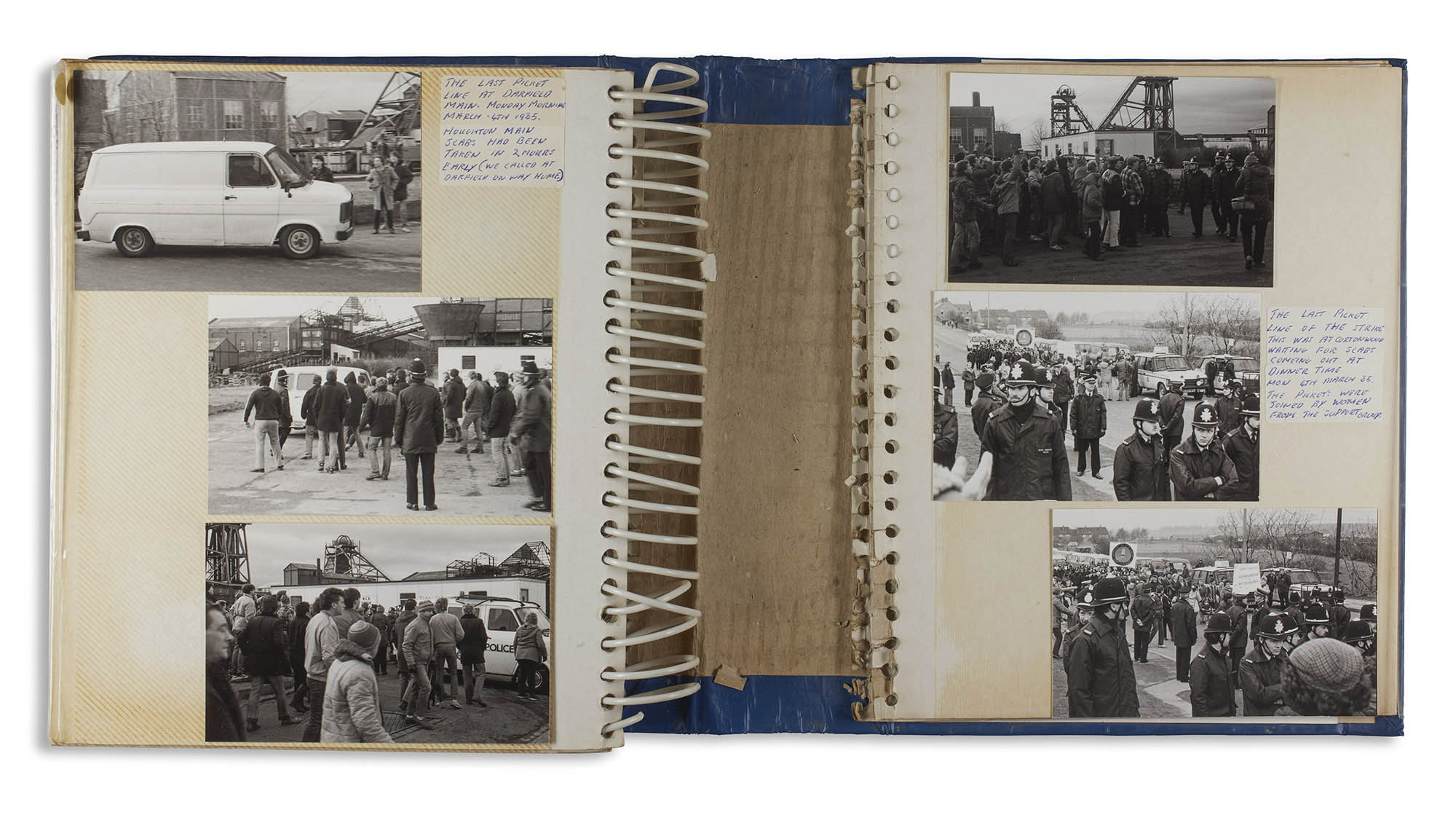

Philip Winnard (British)

Spread from photo album NUM Strike, 12th March 1984, TILL WE WIN

1984

Photo album

© Philip Winnard

The last picket line at Darfield Main. Monday morning March 4th 1985.

Houghton Main scabs had been taken in 2 hours early (we called at Darfield on way home)

The last picket line of the strike. This was at Corton Wood waiting for scabs comeing out at dinner time. Mont 4th March 85. The Picket’s were joined by Women from the Support Group.

Text from the photo album pages above

“The media was a very important aspect of the miners’ strike – the photographs were used against the miners in terms of demonising them,” Blease explains. “Images were used to illustrate violence and chaos in quite demonising and weaponised ways, but then on the other hand photographs were used to debase that media bias – through posters, photojournalists working for left-wing and union press, and people like Sturrock, John Harris, Prince and Imogen Young who were photographing the strike in a more holistic way.” …

Many of the photographers featured were part of the communities that they were documenting. Philip Winnard was one such example, as he was on strike himself from the Barnsley Main Colliery. “When he went on strike, he took his camera along and started recording his experiences when he was picketing,” Blease says. “We wanted to focus on how photographs were used in different ways and shared with friends and colleagues. He compiled these really amazing photo albums and they follow the strike chronologically, starting with the first picket lines and finishing with the return to work marches a year later.”

“They feel like family albums and spare no punches in how they record the strike,” he continues. “There’s violence, the intimidation of strike breakers, fundraising community activities, newslettering – there’s everything, and it gives an intimate familiarity with the event.”

Women also feature heavily throughout the exhibition, highlighting the oft-overlooked role they played in supporting – from those making food in the striking miners’ kitchens to all female picket lines at the collieries. Photographers such as Brenda Prince, who was a member of women’s only photography agency Format, documented this.

“Prince was focusing a lot on women’s roles in the strike,” Blease says. “So miners’ wives, community work, fundraising, picketing themselves, gathering food packages, and they played a very important role. These photographers were not just focusing on the sensational battle that was going on, they were showing how communities were coming together, but also how communities were being destroyed by the dispute, and photography was the medium that was catching this.”

Isaac Muk. “In Photos: The miners’ strike, 40 years on,” on the Huck website 6th March, 2024 [Online] Cited 24/09/2024

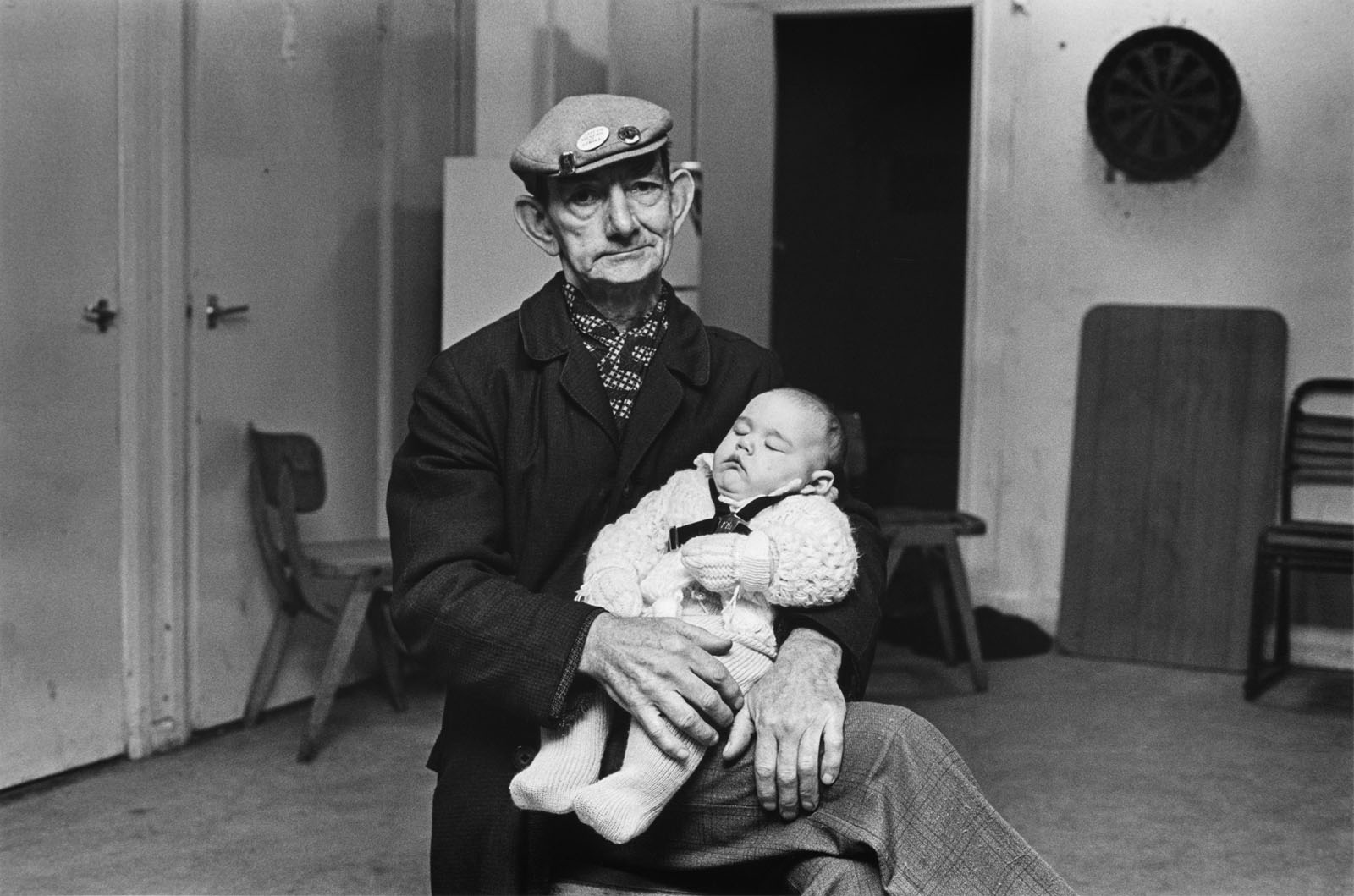

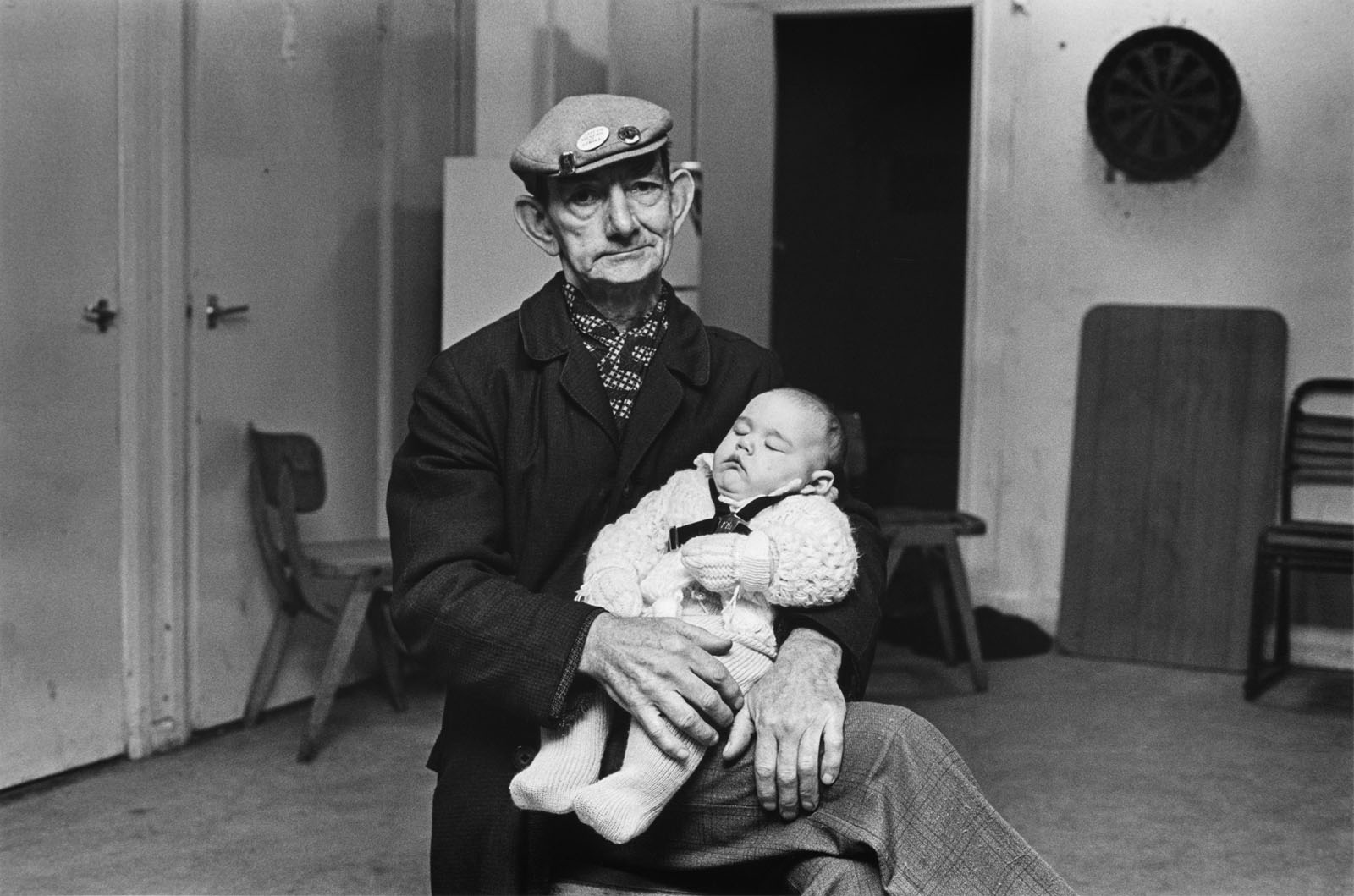

Brenda Prince (British, b. 1950)

Sidney Richmond, retired Pit Deputy, babysitting Sean (3 months old) – first strike baby in the village. Clipstone Colliery, Nottingham

1984-1985

© Brenda Prince

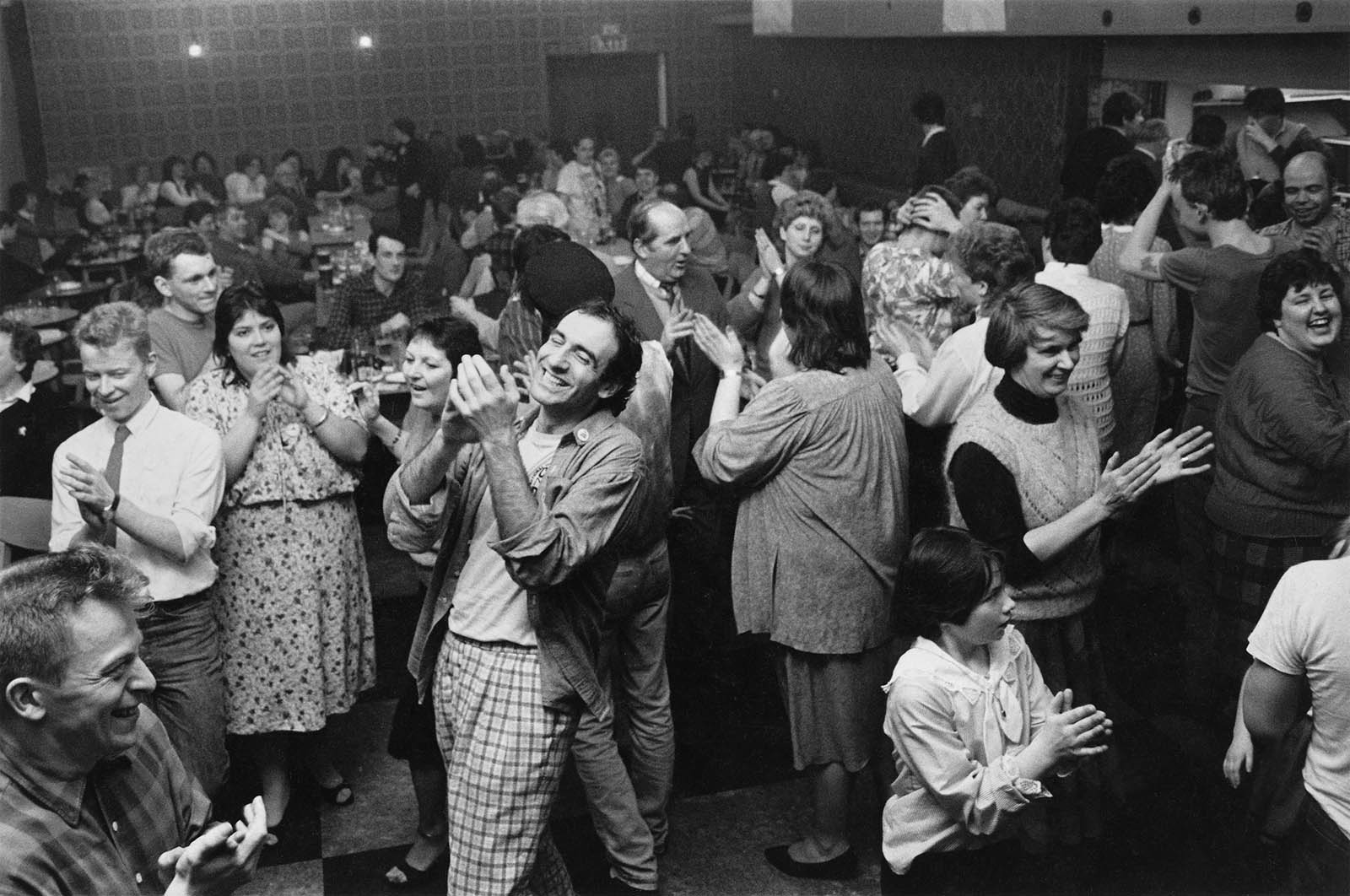

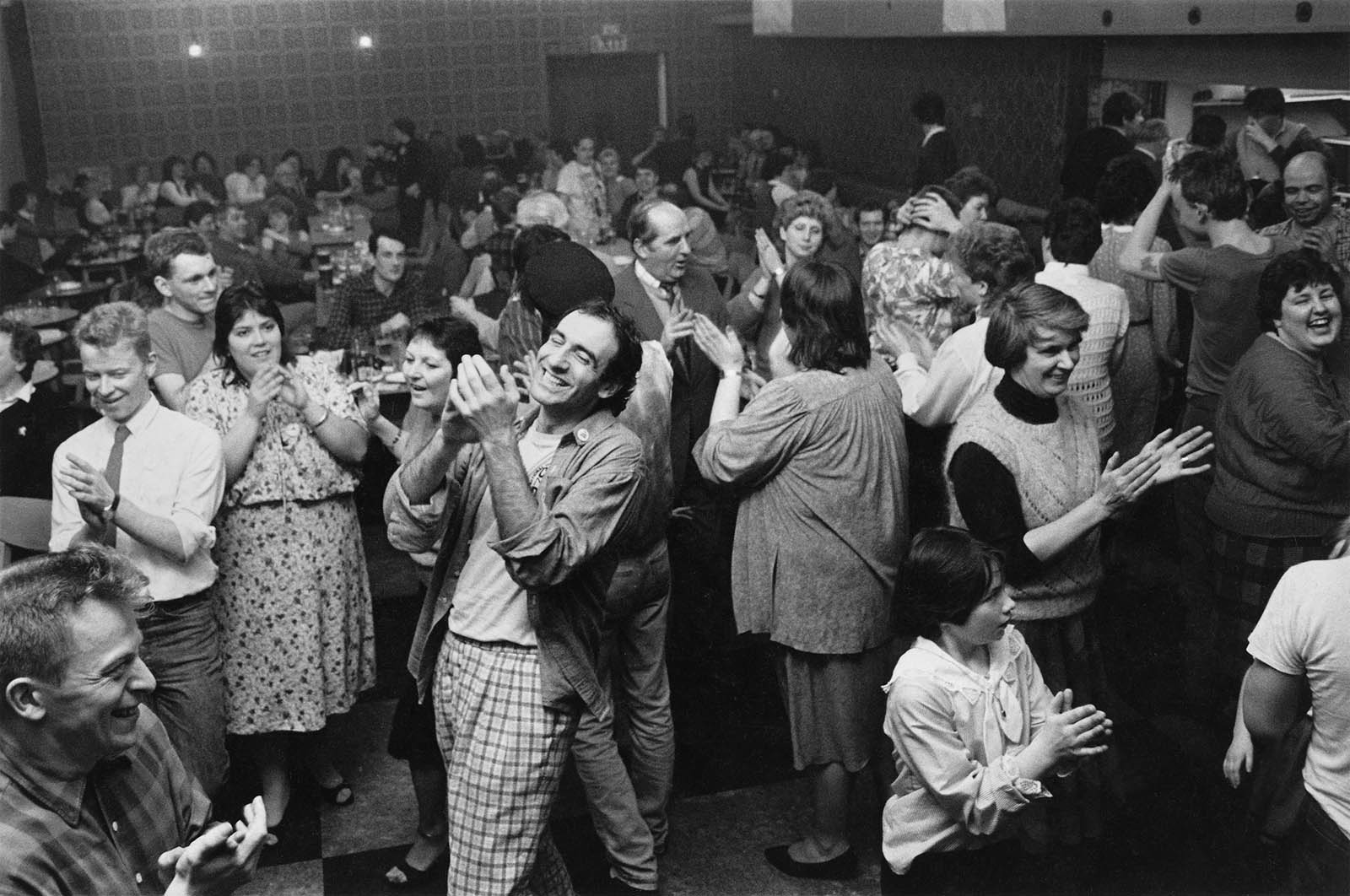

Imogen Young (British)

London’s Lesbian and Gay ‘Support the Miners’ Group take part in David’s Day celebration in Neath Colbren Club

2 March 1985

© Imogen Young

ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 explores the vital role that photography played during this bitter industrial dispute.

To commemorate the 40th anniversary of the miners’ strike, Four Corners is delighted to tour this exhibition from the Martin Parr Foundation. One of Britain’s longest and most violent disputes, the repercussions of the miners’ strike continue to be felt today across the country.

The exhibition looks at the central role photographs played during the year-long struggle against pit closures, with many materials drawn from the Martin Parr Foundation collection. Posters, vinyl records, plates, badges and publications are placed in dialogue with images by photographers, investigating the power and the contradictions inherent in using photography as a tool of resistance. They include photographs by Brenda Prince, John Sturrock, John Harris, Jenny Matthews, Roger Tiley, Imogen Young and Chris Killip, as well as Philip Winnard who was himself a striking miner.

The photographs show some familiar imagery – the lines of police and the violence – but also depict the remarkable community support from groups such as Women Against Pit Closures and the Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners. Photography was used both to sway public opinion and to document this transformative period in British history.

The catalyst for the miners’ strike was an attempt to prevent colliery closures through industrial action in 1984-85. The industrial action, which began in Yorkshire, was led by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and its President, Arthur Scargill, against the National Coal Board (NCB). The Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher opposed the strikes and aimed to reduce the power of the trade unions. The dispute was characterised by violence between the flying pickets and the police, most notably at the Battle of Orgreave. The miners’ strike was the largest since the General Strike of 1926 and ended in victory for the government with the closure of a majority of the UK’s collieries.

Press release from Four Corners

John Harris (British)

Lesley Boulton at the Battle of Orgreave

1984

Gelatin silver print

© John Harris/reportdigital.co.uk

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Photographer Lesley Boulton is attacked by a truncheon-wielding policeman at Orgreave. The picture was published by only one of 17 national newspapers in Britain.

On 18 June, miners came from all over the country to picket the coking plant outside Orgreave village, near Rotherham. I arrived at about 9.15am, with my camera – I was documenting life on the picket line. It was a glorious day: miners were sitting in the sun, or playing football, when suddenly police horses charged out in small groups. They did this twice, then there was a massive charge and they started attacking people. I didn’t see any trigger for this.

People tried to escape across the railway line, which led to a lot of injuries. And there were policemen on foot with short shields, laying about people with truncheons. I was numb with shock. This was violence far in excess of anything I’d ever witnessed: they were whacking people about the head and body with impunity. Some men tried to defend themselves. We couldn’t believe it when the BBC reversed footage on the Six O’Clock News to suggest the miners had attacked the police, and that the police had simply retaliated. [Despite an Independent Police Complaints Commission report in 2015 confirming the reversal, the BBC has never officially accepted this.]

It was chaos. I ran back to the village and hid in a car repair yard. After a few minutes, I came out and photographed one man pinned to a car bonnet, being beaten terribly. At the bus stop, a man was lying on the ground with a chest injury. I was calling to a policeman standing in the road, asking him to get an ambulance, when these two mounted police bore down on me. A man pulled me out of the way just as one of them took a full swipe at my head with his truncheon, and missed.

When I look at this photograph, I wonder what was going through his mind. The police claimed the image was doctored; when I tried to press charges for assault, the director of public prosecutions’ office told me there wasn’t enough evidence. How much did they need?

I don’t take this image personally, because it’s not about me; it’s about something much bigger: an expression of arbitrary power, and what can happen when our masters decide to put us in our place. Besides, I didn’t suffer the way the miners and their families did.

Lesley Boulton quoted in Adrian Tempany. “‘A policeman took a full swipe at my head’: Lesley Boulton at the Battle of Orgreave, 1984,” on The Guardian website 17 December 2016 [Online] Cited 23/09/2024

Philip Winnard (British)

Spread from photo album NUM Strike, 12th March 1984, TILL WE WIN

1984

Photo album

© Philip Winnard

Showing photographs from the Battle of Orgreave

Battle of Orgreave

The Battle of Orgreave was a violent confrontation on 18 June 1984 between pickets and officers of the South Yorkshire Police (SYP) and other police forces, including the Metropolitan Police, at a British Steel Corporation (BSC) coking plant at Orgreave, in Rotherham, South Yorkshire, England. It was a pivotal event in the 1984–1985 UK miners’ strike, and one of the most violent clashes in British industrial history.

Journalist Alastair Stewart has characterised it as “a defining and ghastly moment” that “changed, forever, the conduct of industrial relations and how this country functions as an economy and as a democracy”. Most media reports at the time depicted it as “an act of self-defence by police who had come under attack”. In 2015, the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) reported that there was “evidence of excessive violence by police officers, a false narrative from police exaggerating violence by miners, perjury by officers giving evidence to prosecute the arrested men, and an apparent cover-up of that perjury by senior officers”.

Historian Tristram Hunt has described the confrontation as “almost medieval in its choreography … at various stages a siege, a battle, a chase, a rout and, finally, a brutal example of legalised state violence”.

71 picketers were charged with riot and 24 with violent disorder. At the time, riot was punishable by life imprisonment. The trials collapsed when the evidence given by the police was deemed “unreliable”. Gareth Peirce, who acted as solicitor for some of the pickets, said that the charge of riot had been used “to make a public example of people, as a device to assist in breaking the strike”, while Michael Mansfield called it “the worst example of a mass frame-up in this country this century”.

In June 1991, the SYP paid £425,000 in compensation to 39 miners for assault, wrongful arrest, unlawful detention and malicious prosecution.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Poster for the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 at Four Corners, London showing in the background, Brenda Prince’s photograph Riot police await orders in fields surrounding Orgreave coke works, S. Yorkshire, Miners’ dispute, 1984

Poster for the exhibition ONE YEAR! Photographs from the Miners’ Strike 1984-85 outside of Four Corners, London

BUY THE BOOK FROM BLUECOAT PRESS

Martin Parr Foundation

Martin Parr Foundation supports emerging, established and overlooked photographers who have made and continue to make work focused on Britain and Ireland. We preserve a growing collection of significant photographic works and strive to make photography engaging and accessible for all. We are committed to making the Martin Parr Foundation a place for everyone and to reflect the diversity of British and Irish culture.

Four Corners

Four Corners centre for film and photography has been based in East London for 50 years. We champion creative expression for social change, connecting communities and image-makers to learn skills and create new work. Drawing on our radical history, our exhibitions explore how photography and film can tell stories from the margins, looking to the past to inspire the future.

Four Corners

121 Roman Road, Bethnal Green,

London E2 0QN

Nearest tube: Bethnal Green, Central Line

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Saturday 11am – 6pm

Thursday 11am – 8pm (July and on 31 Aug)

Four Corners website

Martin Parr Foundation website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

You must be logged in to post a comment.