Exhibition dates: 21st September, 2025 – 11th January, 2026

Curators: The exhibition is co-curated by Philip Brookman, consulting curator of the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art, and Deborah Willis, university professor and chair of the department of photography and imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts and director of the Center for Black Visual Culture at New York University.

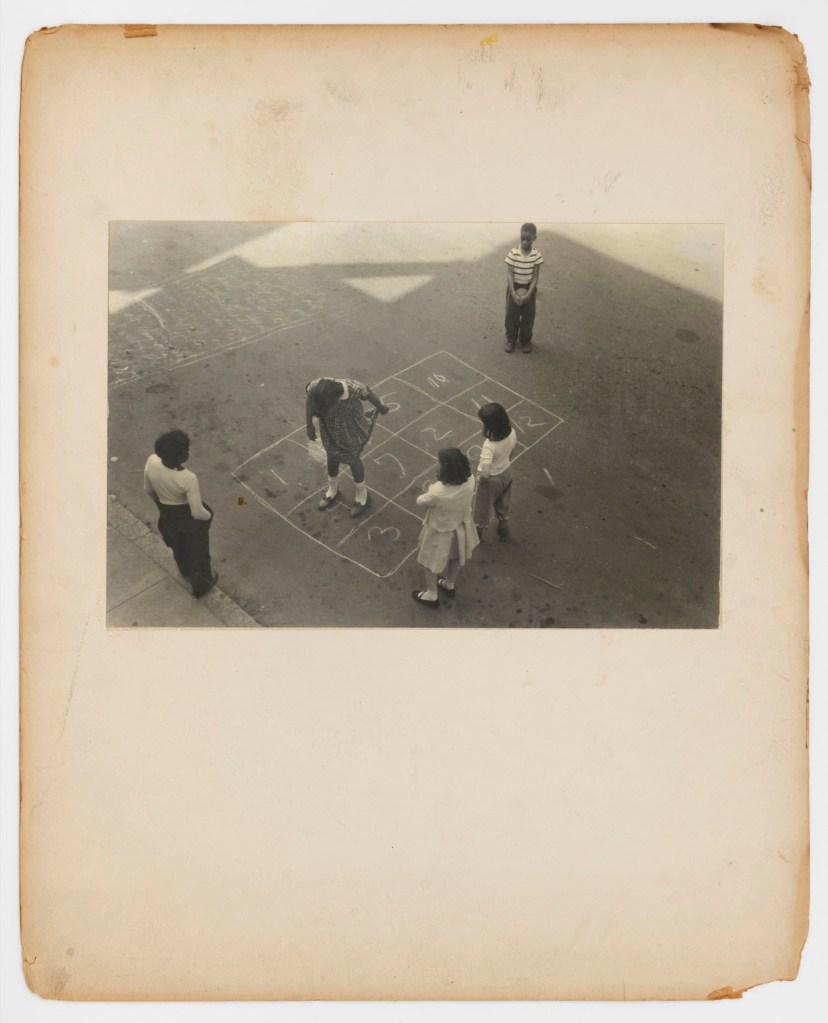

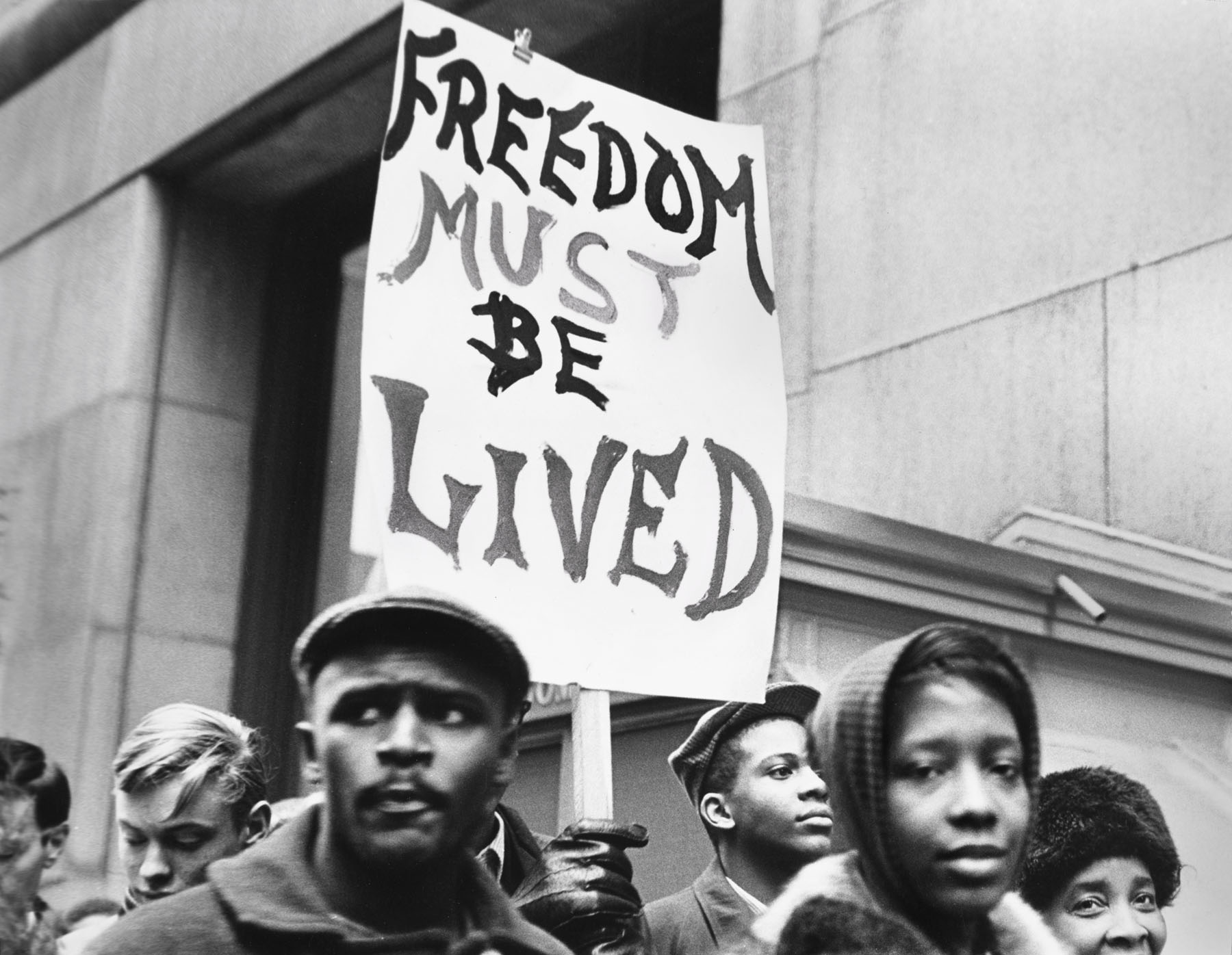

Thomas Ellis (American, 1963-2025)

The Game

1947

Gelatin silver print

21 x 31.8cm (8 1/4 x 12 1/2 in.)

Courtesy of the Darrel Ellis Estate, Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles, and Candice Madey, New York

Photo: Adam Reich

Thomas Sayers Ellis (October 5, 1963 – July 17, 2025) was an American poet, photographer, musician, bandleader and teacher.

“There’s nothing like a photograph for reminding you about difference. There it is. It stares you ineradicably in the face”

~ Professor Stuart Hall, 2008

This looks to be a “worthy” exhibition on photography and the Black Arts movement but without having seen it in person there is little specific comment I can make about the exhibition. However, some thoughts on the photographs in this posting are possible.

It is a joy for me to be able to learn more about an important area in photographic history, vis a vis “the role of African American photographers and artists working with photographs in developing and fostering a distinctly Black perspective on art and culture.” (Text from the NGA website)

There are many photographers in the posting who I have never heard of before, whose work I have never seen, and I always like learning, for in learning you may gain some small amount of wisdom and appreciation of different cultures and points of view. I have added biographical information for each artist to their images where possible.

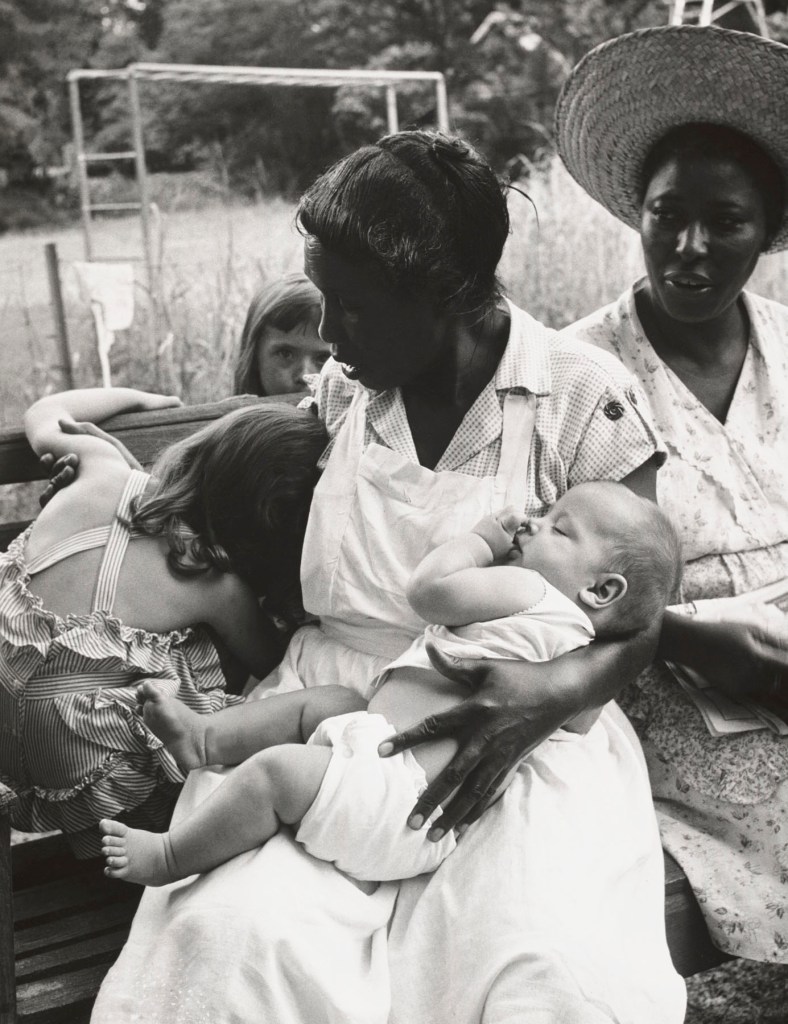

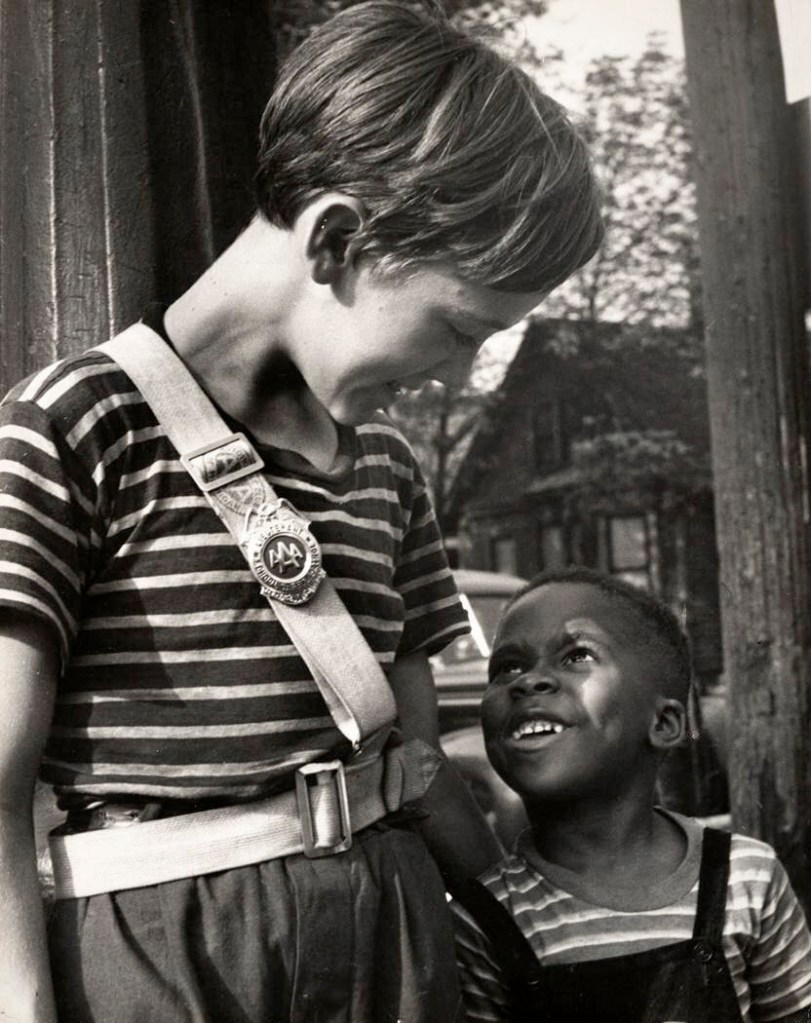

The photographs from the period 1955-1985 mark a shift away from an aesthetic and formalist way of looking at the image where the role of the photographer and the reception of the print was in its primacy (the 1950s-1960s) “towards a more polemical, critical and cultural analysis by Tagg, Sekul, Solomon-Godeau and others in the 1980s and 90s. These shifts from the pictorial to the political … decentre the photographer and bring into focus the photographed and viewing subjects…”1

In these photographs it is not so much the primacy of the artist, the aesthetics of the image, nor the photographs status as art objects, but the people within the images that are the focus of attention. They bring to the forefront of the viewer’s consciousness (or should do) the racial politics at work within photography in the context of discussions around race and representation and the ongoing legacies of Western imperialism.

The photographs demonstrate “that if we do not recognise the historical and political conjunctures of racial politics at work within photography, and their effects on those that have been culturally erased, made invisible or less than human by such images, then we remain hemmed within established orthodoxies of colonial thought concerning the racialised body, the subaltern and the politics of human recognition.”2

They bring to light (aha!) “new ways of seeing that bring the Other into focus”, photographs that challenge us to acknowledge the structural racism that is embedded in daily life which produces adverse outcome for people of color. Through such an acknowledgement we may open up a personally and culturally transformative dialogic space, “a “space of possibilities” where participants listen, engage with, and even transcend their own viewpoints to see issues from multiple angles” – as there can never be a single view point when we “examine” social groups that are subaltern (groups that have been marginalised or oppressed).

From a distance this seems to be one of the problems of the exhibition. It’s all so worthy and righteous, full of the injustice of it all, and perhaps that’s as it should be for those were the times and the culture from which these photographs emerged. But I can’t help but get the feeling that this exhibition seems to feel and read more like a study in cultural anthropology, more a sociological statement than any celebration of Black history and culture from the period. Speaking from the standpoint of a white, middle class artist and writer, there seems to be little joy to be had here – to me one of the essential elements of Black culture, the joy of gospel, jazz, laughter, love – but I’m supposedly on the inside looking out (or is it the outside looking in!). Who am I to say.

What is undeniable is that, as Professor Stuart Hall so succinctly observes, there is nothing like a photograph to remind you of difference, to challenge your perceptions on how you view and interact with the world around you, to open up new ways of seeing. As such, the photographs in this exhibition may allow us deeper insight into the “conditions of our own becoming” (while human beings have agency, the circumstances under which they act and develop their humanity are largely shaped by existing material, social, and historical conditions that they did not choose) of the people that live around us, even as we acknowledge that there is no singular point of view, that cultural forms have no single determinate meaning, and that no one, and “no discipline, whether art- or photo-history, or ethnography or geography, speaks with a single voice.”1

Not one way of seeing, but multiple ways of seeing our fellow human beings.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Catherine De Lorenzo. “Oceanian imaginings in French photographic archives,” in History of Photography, Issue 2, Volume 28, 2004, pp. 137-184

2/ Text from the description of the book by Mark Sealy. Decolonising the Camera: Photography in Racial Time. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 2019.

The book examines how Western photographic practice has been used as a tool for creating Eurocentric and violent visual regimes, and demands that we recognise and disrupt the ingrained racist ideologies that have tainted photography since its inception in 1839.

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Art, Washington for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“The work that was done by artists and photographers before, during, and after the Black Arts Movement establishes a strategy of community engagement. It is that engagement that allows communities to define themselves and also to engage people in new forms of looking.”

Co-curator Philip Brookman

Cultural forms set the wider terms of limitation and possibility for the (re)presentation of particularities and we have to understand how the latter are caught in the former in order to understand why such-and-such gets (re)presented in the way it does. Without understanding the way images function in terms of, say, narrative, genre or spectacle, we don’t really understand why they turn out the way they do.

Secondly, cultural forms do not have single determinate meanings – people make sense of them in different ways, according to the cultural (including sub-cultural) codes available to them. For instance, people do not necessarily read negative images of themselves as negative …

Richard Dyer. The Matter of Images: Essays on Representations. London: Routledge, 1993, pp.2-3

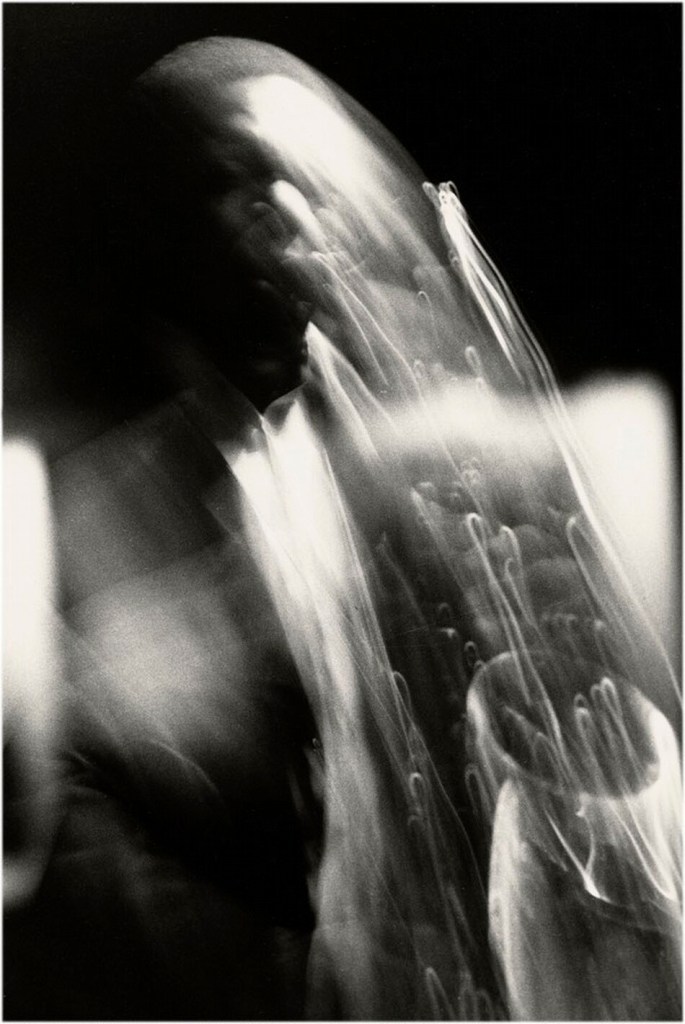

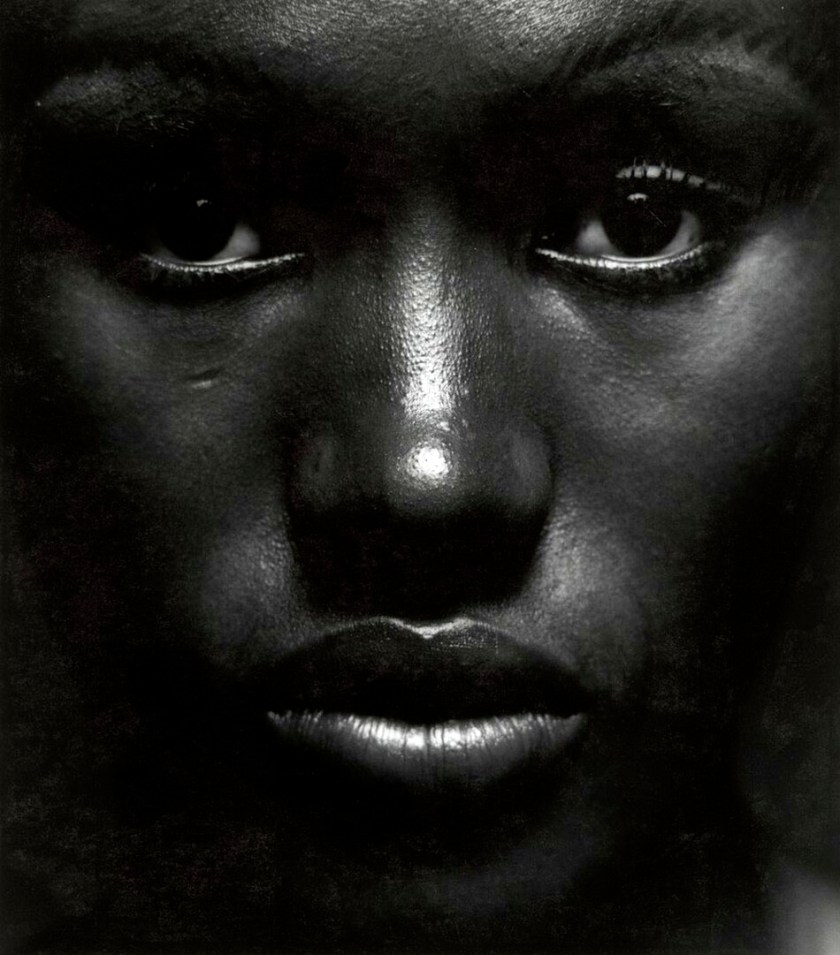

Adger Cowans (American, b. 1936)

Coltrane at the Gate

1961

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Charina Endowment Fund

Adger Cowans (American, b. 1936)

Adger Cowans is a pioneering photographer and one of the founding members of the Kamoinge Workshop, a collective that played a key role in shaping Black photography in the 1960s and beyond.

In 1958 Cowans worked as an assistant to renowned photographer Gordon Parks. Throughout the 1960s Cowans became involved with influential groups associated with the Black Arts Movement, including Group 35 and Afri-COBRA, which he joined in 1968.

His photographic work spans a wide range of approaches and subjects, from street photography in Harlem to documenting major historical events like the rallies and the funeral of Malcolm X. He also captured iconic jazz musicians, including John Coltrane and Pharoah Sanders.

Text from the National Gallery of Art website

Frank Dandridge (American, b. 1938)

Blinded Birmingham Church Bombing survivor, Sarah Jean Collins, Birmingham, AL, 1963

“Clutching robe in hospital bed, Sarah Jean Collins was near bomb when it exploded in church. Her sister was killed. It will be weeks before she knows whether she can see again.”

September 27, 1963

Gelatin silver print

Overall: 35 x 50 cm (13 3/4 x 19 11/16 in.)

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

© Frank Dandridge

Photo: Frank Dandridge / The LIFE Picture Collection / Shutterstock

Frank Dandridge is a freelance photojournalist who worked mainly for Life Magazine in the 60’s. He covered numerous assignments, including, The Harlem Riots in 1964, Dr. King’s March on Washington, in 1963, and the terrible Birmingham Bombing in 1963. His photos also appeared in Look, Saturday Evening Post, Pageant, Paris Match, Good Housekeeping, Quick Magazine, the Canadian Film Board, Playboy, and many other national magazines. He won an Art Director’s Award for his photo essay, “The Two Faces of Harlem”, that appeared in Look magazine. His work included photographing many celebrities, including, Bobby Kennedy, Muhammad Ali, President Johnson, Dr. Martin Luther King, Frank Sinatra, The Supremes, Sammy Davis, Jr., and Jimmy Hoffa.

Text from the IMBd website

The photos that Frank Dandridge shot for LIFE magazine paint a vivid portrait of violence and race in 1960s America. He reported on riots in Harlem, in Watts, and in Newark,. He was in Selma, Alabama when Martin Luther King marched in the days immediately after Bloody Sunday. Dandridge’s most famous photo is of Sarah Collins, a 12-year-old girl whose eyes were in bandages after the bombing of a Sunday school class at the16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. That bombing killed four girls, including Collins’ sister, while wounding many others and leaving Collins blind in one eye. The image of Collins in her hospital bed made vivid for America the cruelty of this horrific bombing by four men who were members of a splinter group of the Klu Klux Klan.

Bill Syken. “Race in the 1960s: The Photography of Frank Dandridge,” on the LIFE website Nd [Online] Cited 26/11/2025

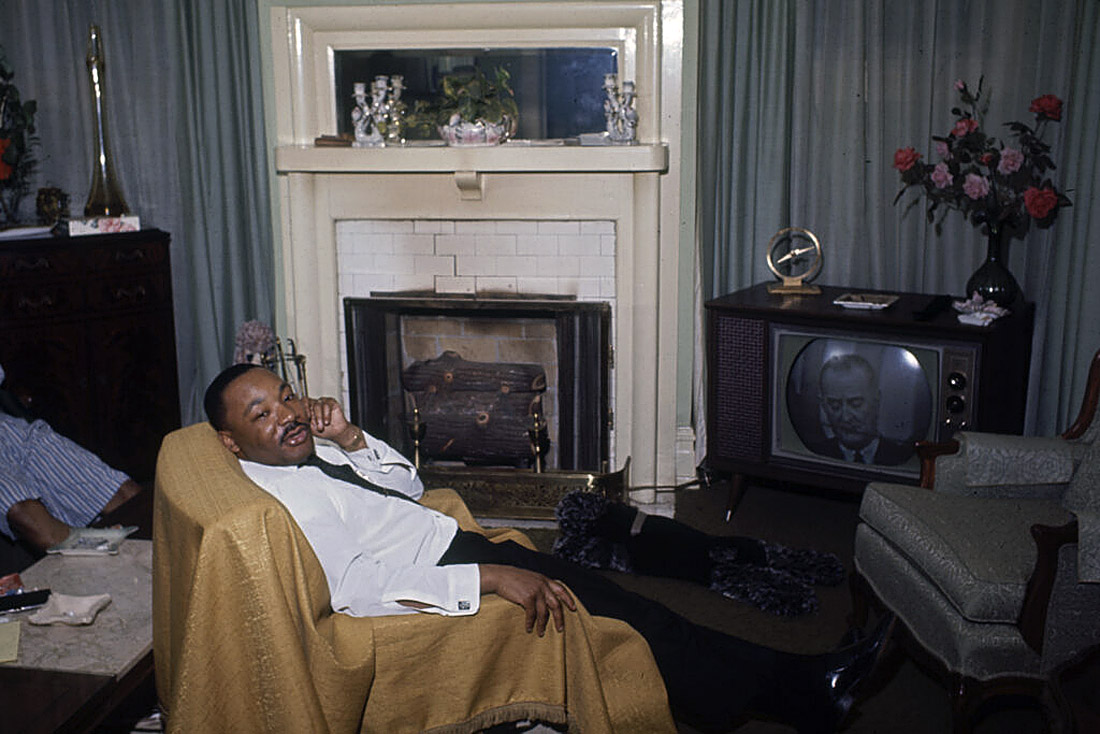

Frank Dandridge (American, b. 1938)

Martin Luther King and other civil rights leaders watched President Lyndon B. Johnson speak on television

1965

Gelatin silver print

© Frank Dandridge

Photo: Frank Dandridge / The LIFE Picture Collection / Shutterstock

Used under fair use for the purposes of education and research

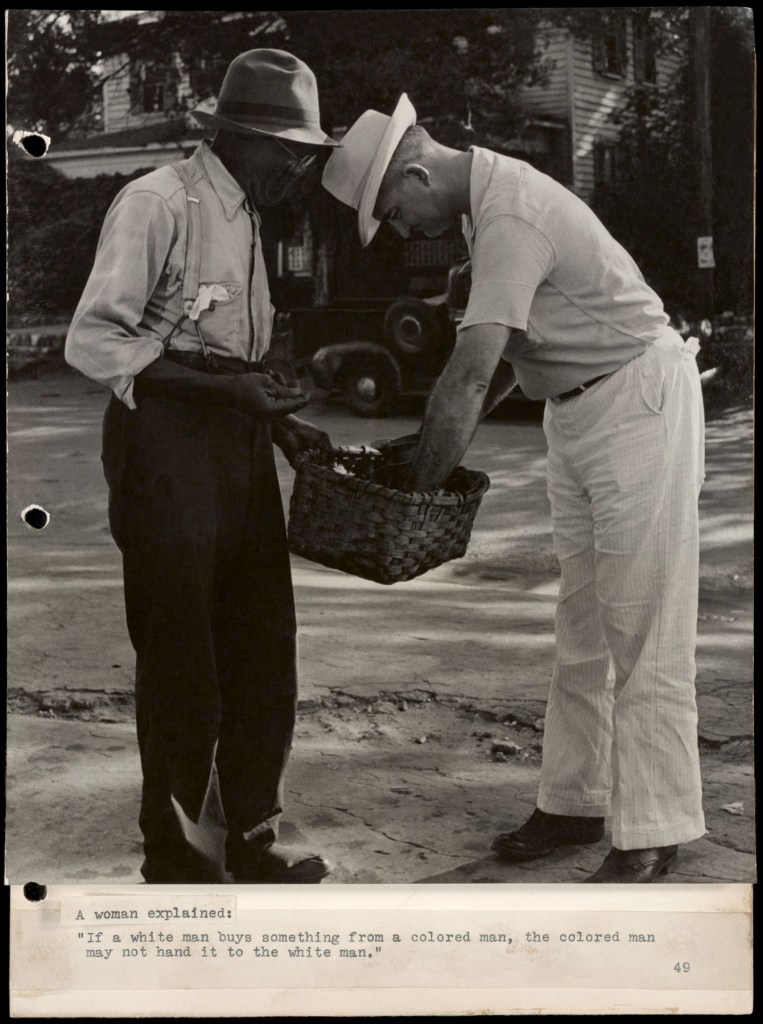

Racism

Racism, when it is embedded in the structures, policies and practices of our social and political institutions can be termed “institutional”. Institutional racism, which will be described by the authors more fully below, is reflected in professional practice and working methods that result in racialized disparities. Frantz Fanon, psychiatrist and political philosopher, stands out as one of the earliest academics to explore the nature of racism from a psychosocial perspective. Fanon (1967) talked of “vulgar racism in its biological form”, which was evident for several hundreds of years, being replaced in the mid-20th century by “more subtle forms” (p. 35). In a study of Fanon’s clinical psychology and social theories, McCulloch (1983) refers to this new racism as “cultural racism” – describing this as “a more sophisticated form [of racism] in which the object is no longer the physiology of the individual but the cultural style of a people” (p. 120). Cultural racism believes that the dominant group’s culture is superior to the seemingly “lower” minority groups.

Cultural racism champions the supremacy of cultures. Commonly, some version of European culture or, more specifically, white European culture, rather than the white “race” (Amin, 1989), thereby producing a situation of racism without “races” (Balibar, 1991). It was the American civil leaders Stokely Carmichael (later Kwame Ture) and Charles V. Hamilton in their 1967 book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation (Carmichael & Hamilton, 1967), who first described institutional racism:

It takes two, closely related forms … we call these individual racism and institutional racism. The first consists of overt acts by individuals … the second type is less overt, far more subtle, less identifiable in terms of specific individuals committing acts … and thus receives far less public condemnation than the first type. (p. 2)

Institutional racism forms an array of broader structural racism processes “that exclude … substantial numbers of members of particular groups from significant participation in major social institutions” (Henry & Tator, 2005, p. 352). According to minority mental health models like the racism-induced reactive negative emotionality cycle (Lazaridou & Heinz, 2021), structural racism and institutional racism result in experiences of rejection and emotional alienation in public spaces for Black people and People of Color (Lentin, 2015).

Structural racism in employment, earnings and credit may mutually limit equal access to quality, affordable accommodation. However, when public spaces are sites of surveillance, intimidation and frequent hostility by the police or by ordinary citizens, then the structure of social situations, such as even leaving one’s house and speaking in public, are filled with stress, anxiety, and fear (Chou et al., 2012; Sibrava et al., 2013). There is pervasive evidence that structural racism has destructive impacts on the health and wellbeing of patients from minority groups, including migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers (Alvarez et al., 2016; Bailey et al., 2017; Graham et al., 2016; Noh & Kaspar, 2003).

Felicia Lazaridou and Suman Fernando. “Deconstructing institutional racism and the social construction of whiteness: A strategy for professional competence training in culture and migration mental health,” in Transcult Psychiatry, 2022 Apr 4; 59(2), pp. 175-187.

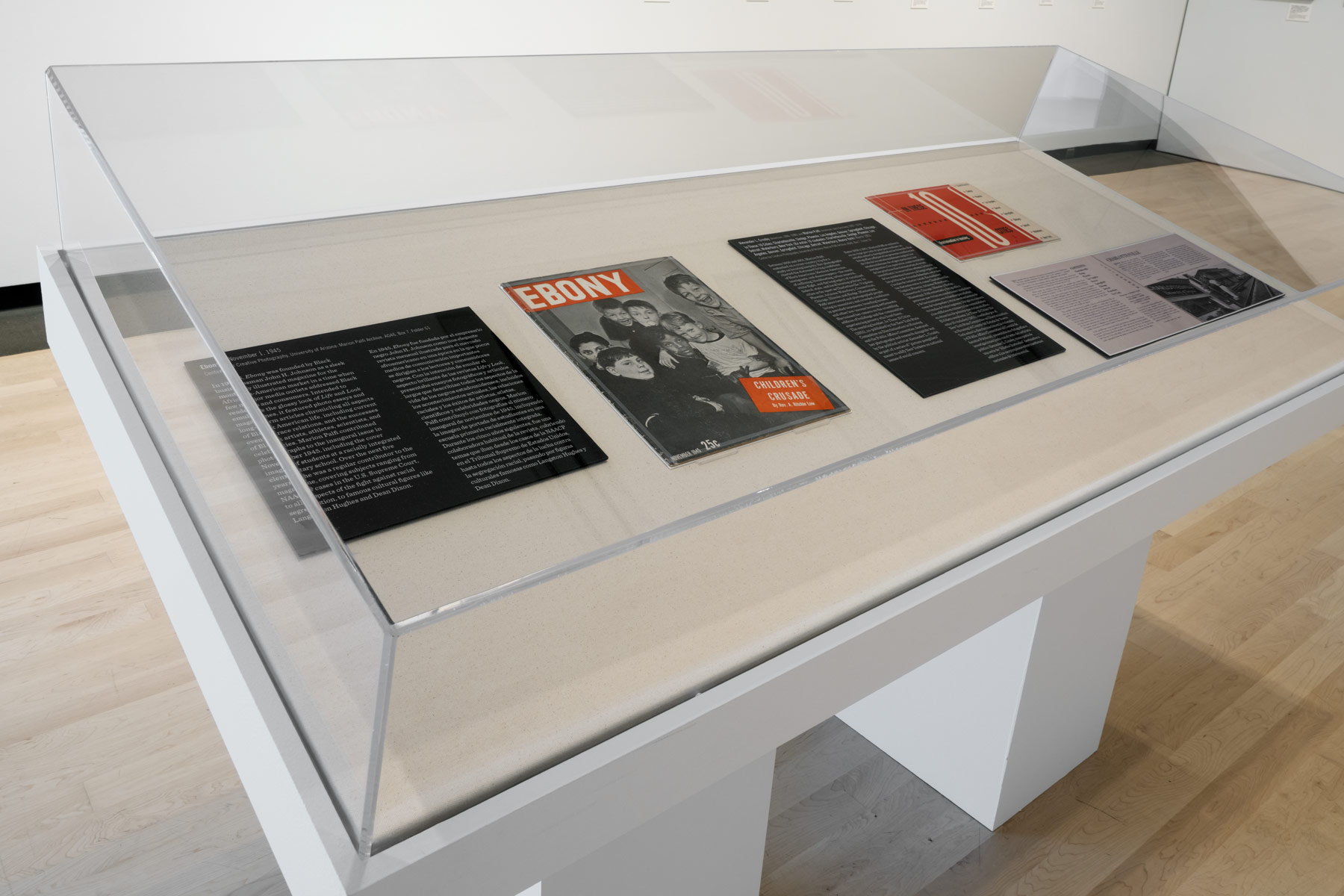

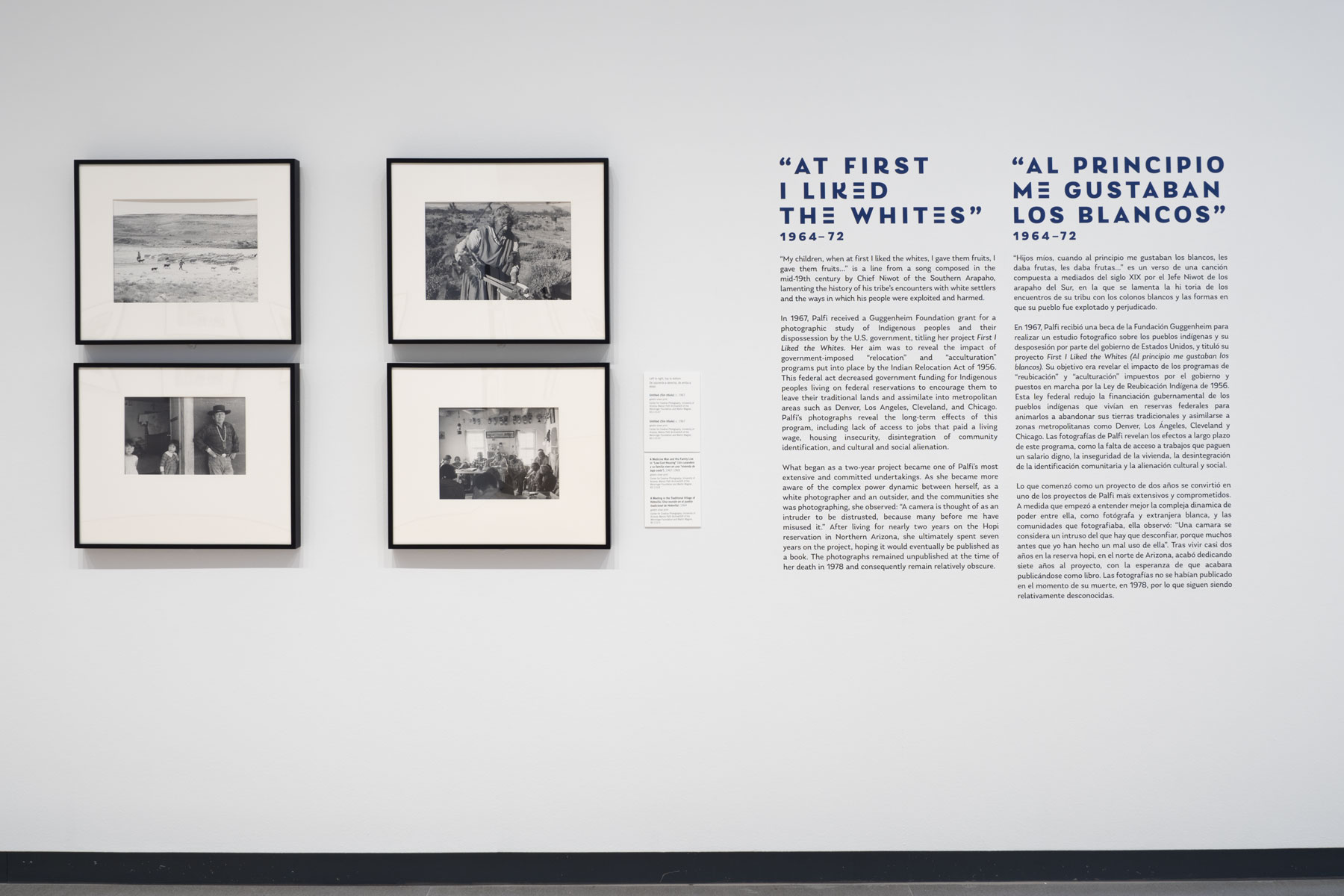

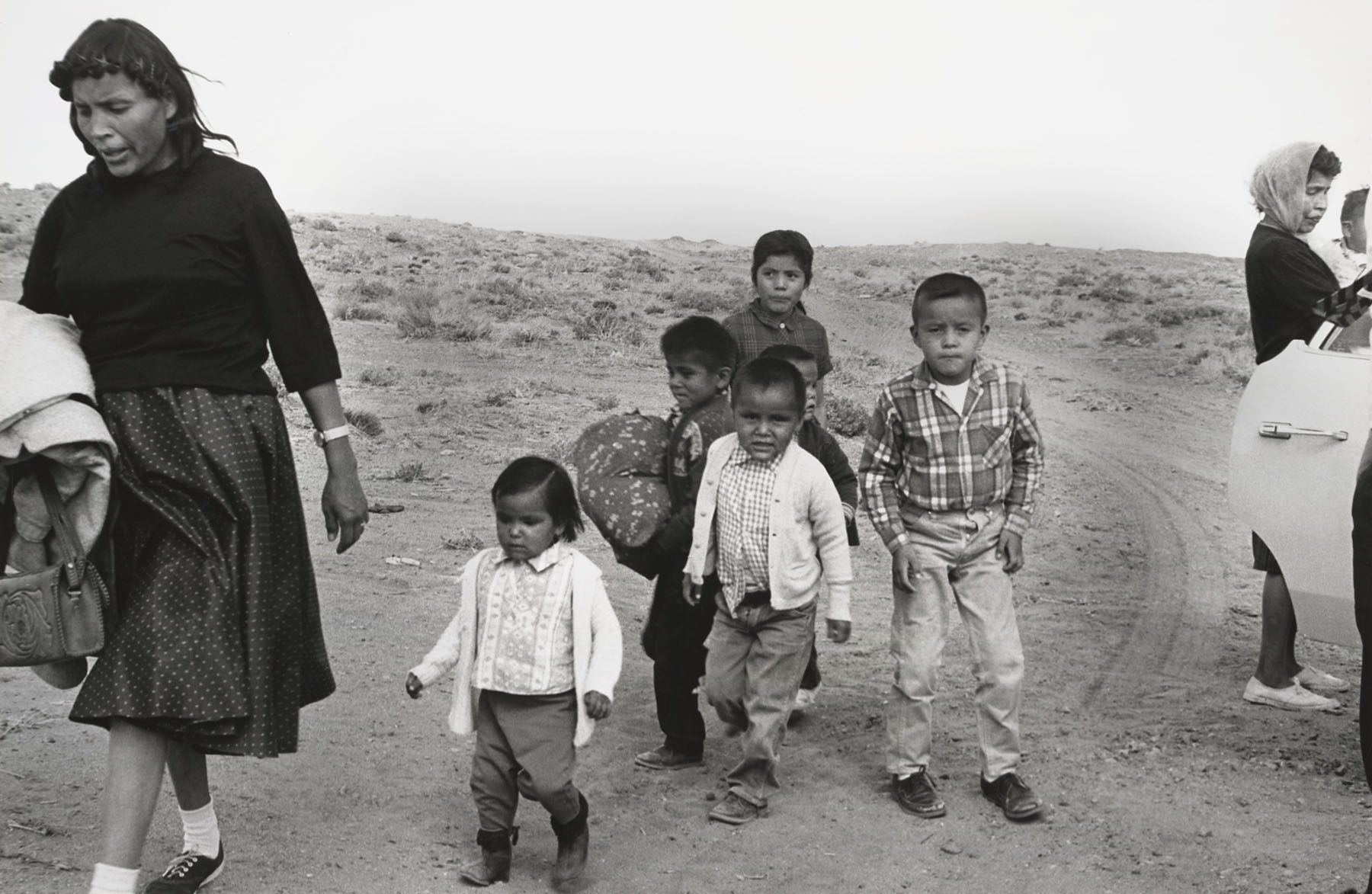

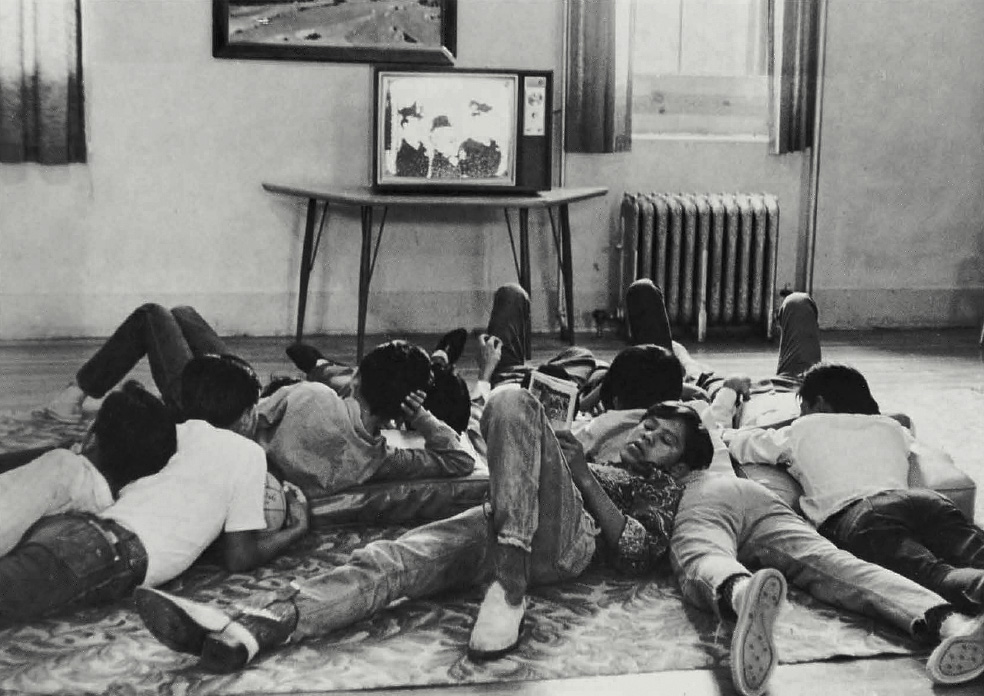

Installation view of the exhibition Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955-1985 at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, September 2025 – January 2026

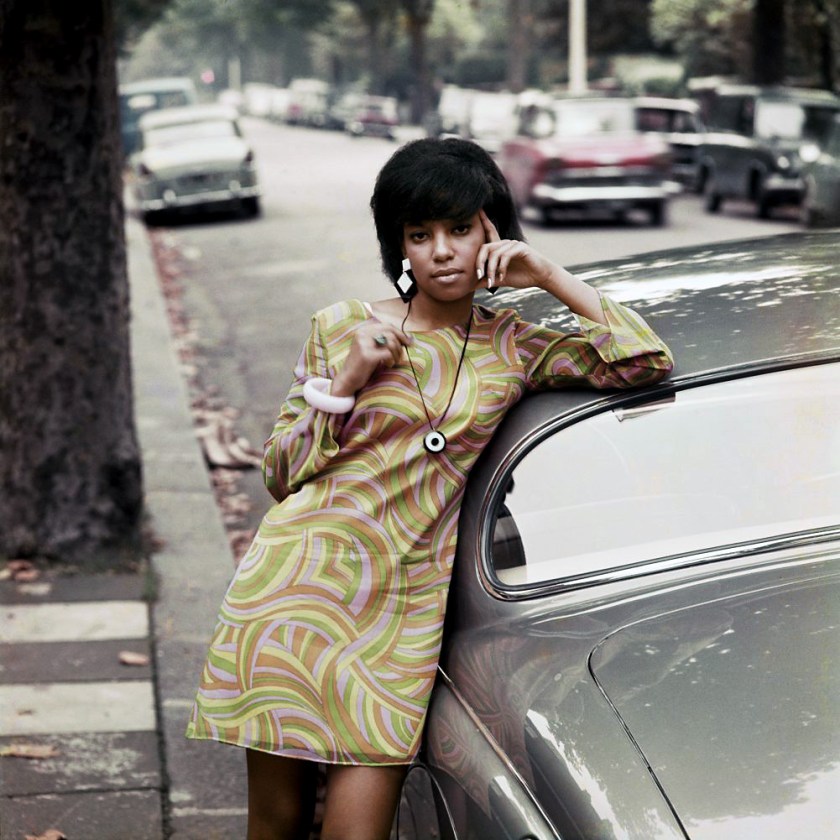

James Barnor (Ghanaian, b. 1929)

Drum cover girl Erlin Ibreck, Kilburn, London

1966, printed 2023

Chromogenic print

29 × 29cm (11 7/16 × 11 7/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© James Barnor / Courtesy Galerie Clementine de la Feronnière

In the tradition of Black African photographers such as Malick Sidibé, Seydou Keïta and Sanlé Sory, Barnor’s photographs present people of all ages and all walks of life – whether in Accra, Ghana or in the suburbs of London, England – through direct and honest studio portraits or in more candid documents of the communities that surrounded him. …

Barnor’s photographs plant the seed of equality and happiness as a way of transmitting this knowledge to others. “He is a living archive, a link between the birth of photography in West Africa and the development of the discipline for the modern era.”2 It is his passion and feeling for the practice of photography, the stories that it tells and his engagement with the spirit of the people that he encounters – as a conversation between equals – that intuitively ground his work in the history of photography and the history of Black culture and makes them forever young.

Marcus Bunyan. “It’s late, but it’s better late than never,” on the Art Blart website October 17, 2021 [Online] Cited 26/11/2025

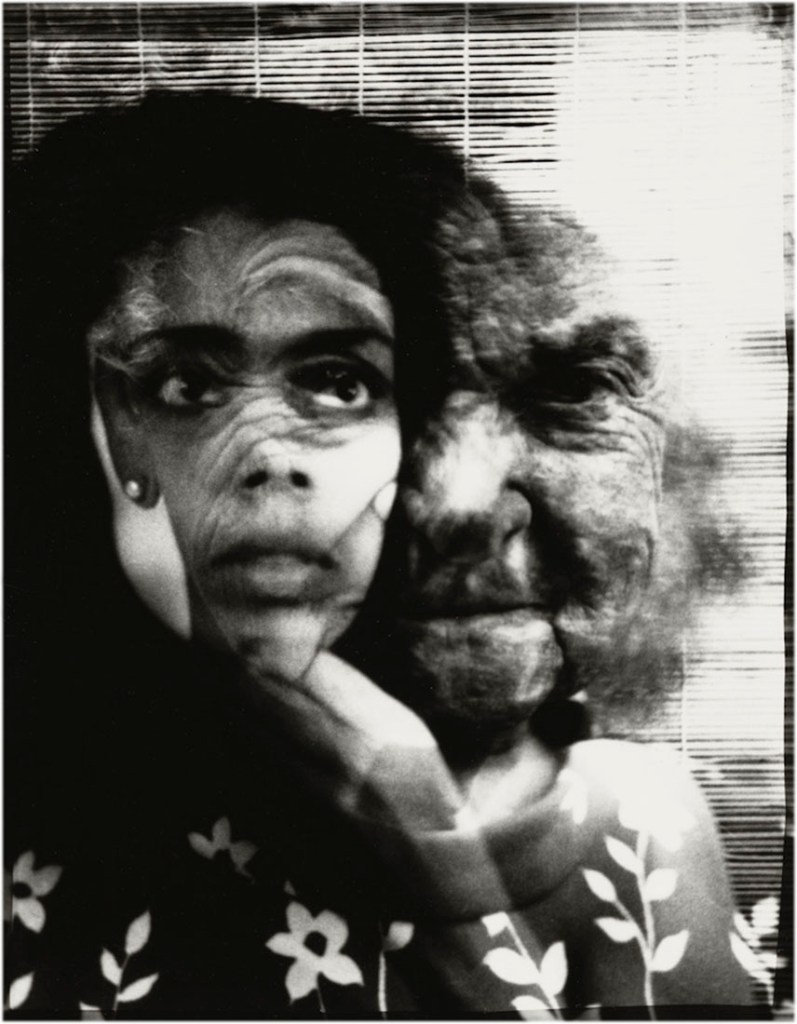

Ralph Arnold (American, 1928-2006)

Above this Earth, Games, Games

1968

Collage and acrylic on canvas

Overall: 114.3 x 114.3 cm (45 x 45 in.)

Collection of Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College, Chicago

Photo: P.D. Young / Spektra Imaging

During the tumultuous 1960s and 70s, the prolific artist Ralph Arnold (1928-2006) made photocollages that appropriated and commented upon mass media portrayals of gender, sexuality, race and politics. Arnold’s complex visual arrangements of photography, painting and text were built upon his own multilayered identity as a black, gay veteran and prominent member of Chicago’s art community…

Text from the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago

Ralph Arnold (American, 1928-2006)

Soul Box

1969

Assemblage with found objects and collage on Masonite

Framed: 71.1 x 56.8 x 14.9cm (28 x 22 3/8 x 5 7/8 in.)

Private collection of Courtney A. Moore

Photo: Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Photography at Columbia College Chicago

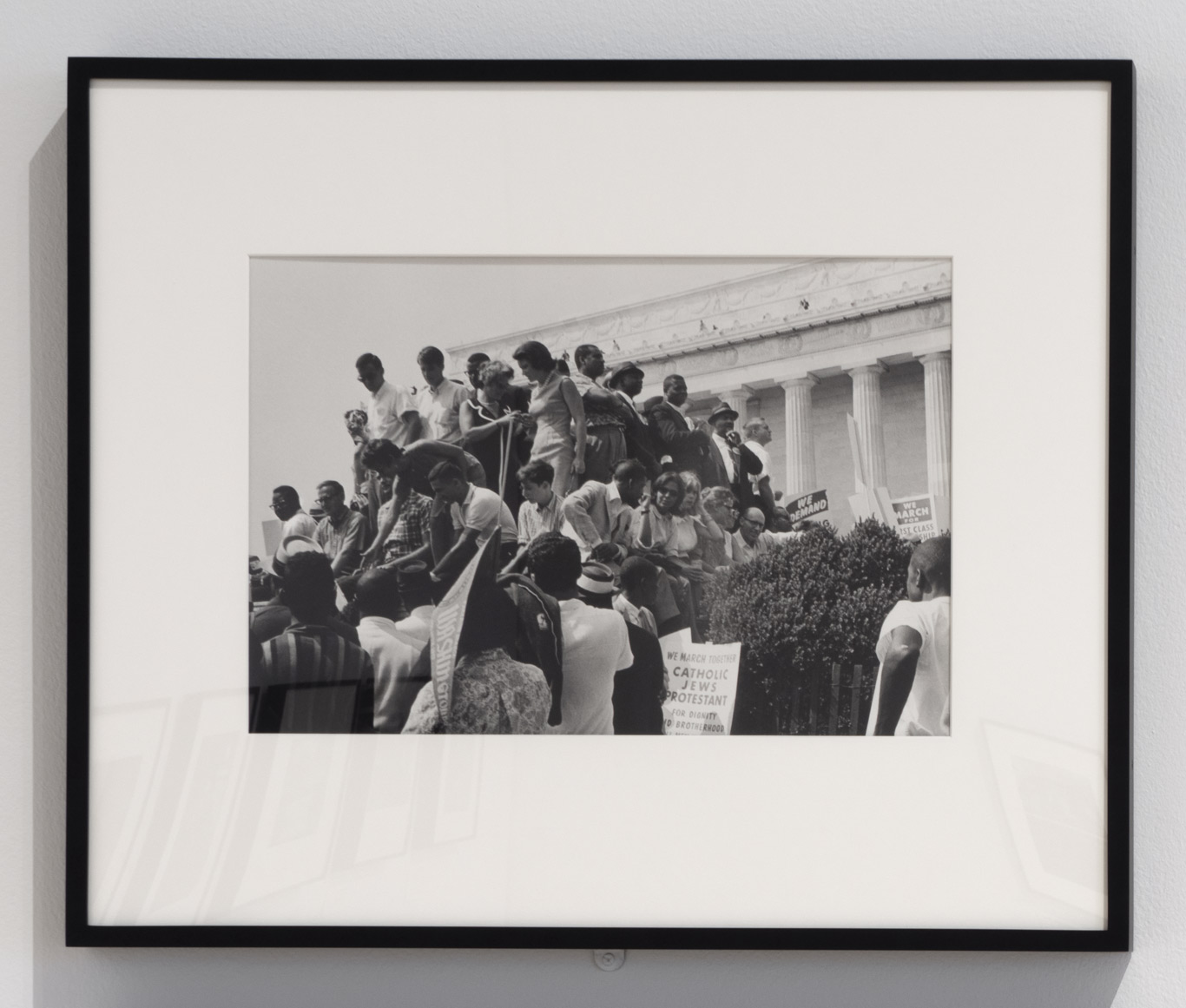

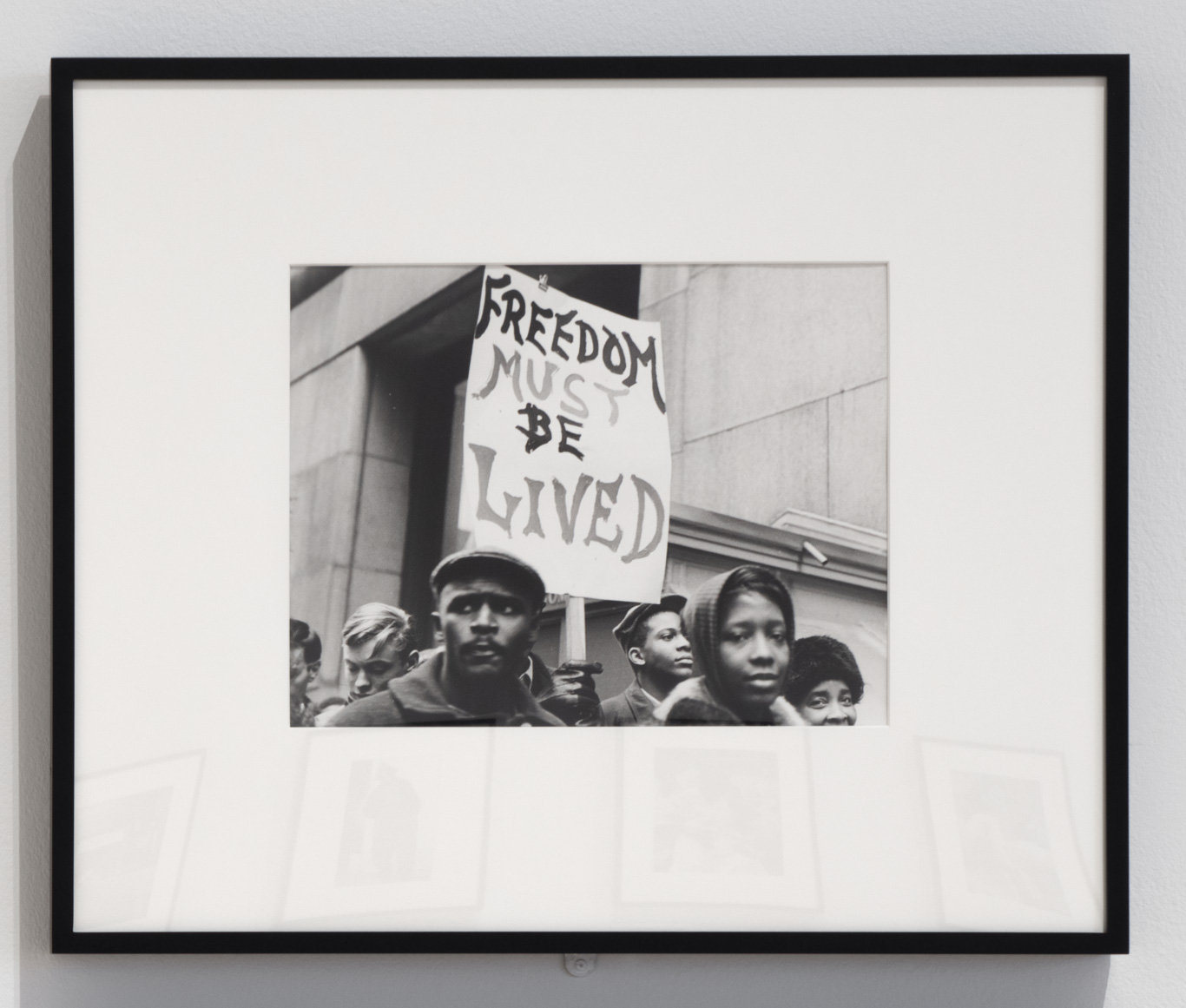

The first exhibition to consider photography’s impact on a cultural and aesthetic movement that celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

Uniting around civil rights and freedom movements of the 1960s and 1970s, many visual artists, poets, playwrights, musicians, photographers, and filmmakers expressed hope and dignity through their art. These creative efforts became known as the Black Arts Movement.

Photography was central to the movement, attracting all kinds of artists – from street photographers and photojournalists to painters and graphic designers. This expansive exhibition presents 150 examples tracing the Black Arts Movement from its roots to its lingering impacts, from 1955 to 1985. Explore the bold vision shaped by generations of artists including Billy Abernathy, Romare Bearden, Kwame Brathwaite, Roy DeCarava, Doris Derby, Emory Douglas, Barkley Hendricks, Barbara McCullough, Betye Saar, and Ming Smith.

Text from the NGA website

Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955-1985 investigates the role of African American photographers and artists working with photographs in developing and fostering a distinctly Black perspective on art and culture. The Black Arts Movement was a uniquely American creative initiative, closely linked to the civil rights movement and comparable to the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s in its impact. Through new institutions and publications, Black writers, musicians, filmmakers, and visual artists explored ways their art could further the American civil rights movement and communicate messages of Black history and identity. Photography and the Black Arts Movement reveals how studio and street photographers, photojournalists, painters, conceptual artists, graphic designers, and community activists used photography to cut across traditional racial boundaries, express messages of empowerment, and advance social justice.

Bringing together some 150 works by more than 100 artists, Photography and the Black Arts Movement also includes objects from Africa, the Caribbean region, and Great Britain, representing artistic dialogues created through travel, migrations, and international engagement with the social, political, and cultural ideas that propelled the movement. Among the artists included are Billy Abernathy, Anthony Barboza, Romare Bearden, Dawoud Bey, Frank Bowling, Kwame Brathwaite, Ernest Cole, Adger Cowans, Roy DeCarava, Emory Douglas, Louis Draper, David C. Driskell, Samuel Fosso, Charles Gaines, Barkley Hendricks, Danny Lyon, Barbara McCullough, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Gordon Parks, Adrian Piper, Juan Sánchez, Coreen Simpson, Betye Saar, Jamel Shabazz, Lorna Simpson, Ming Smith, Frank Stewart, and Carrie Mae Weems.

The exhibition is organised by the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Text from the NGA website

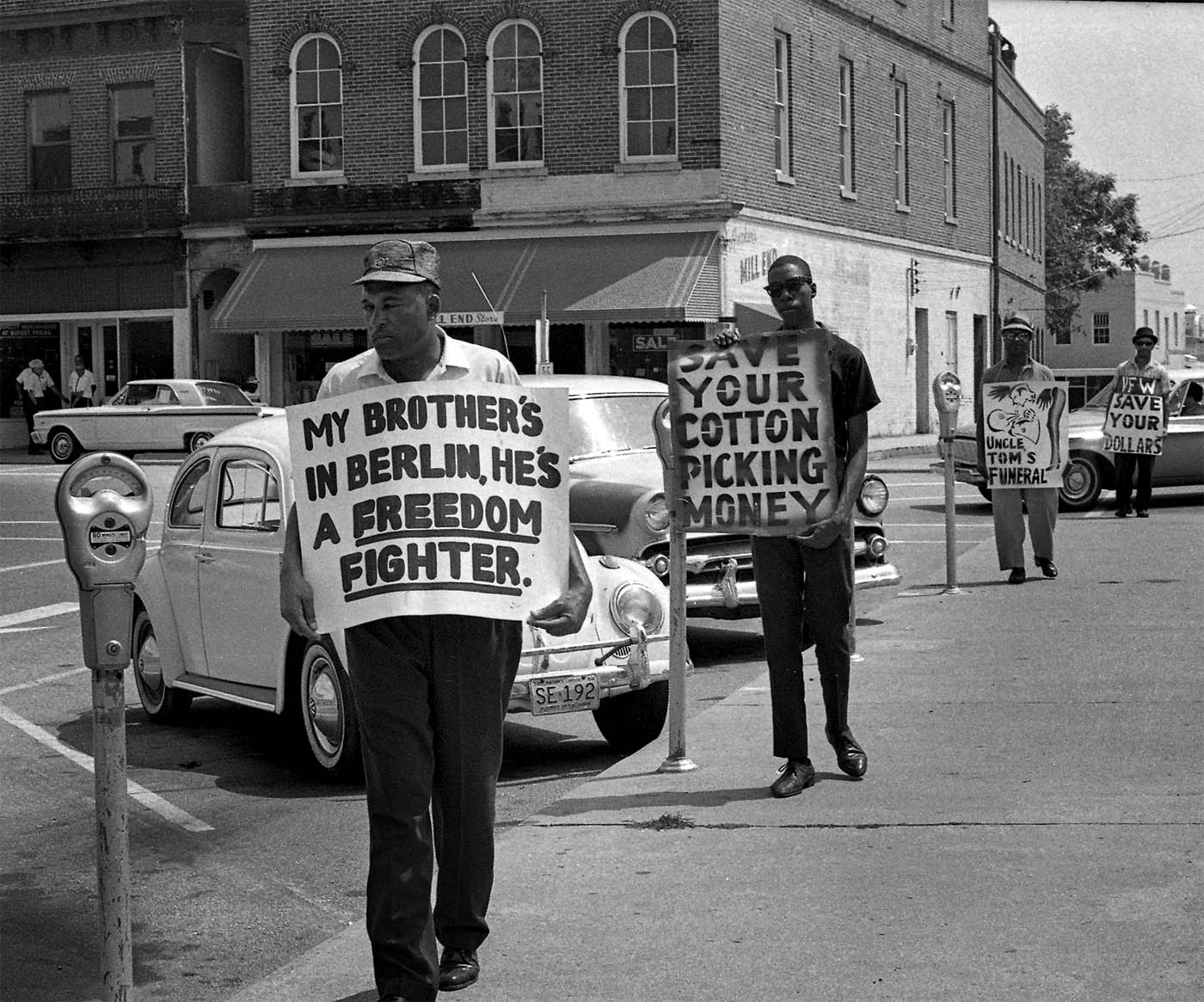

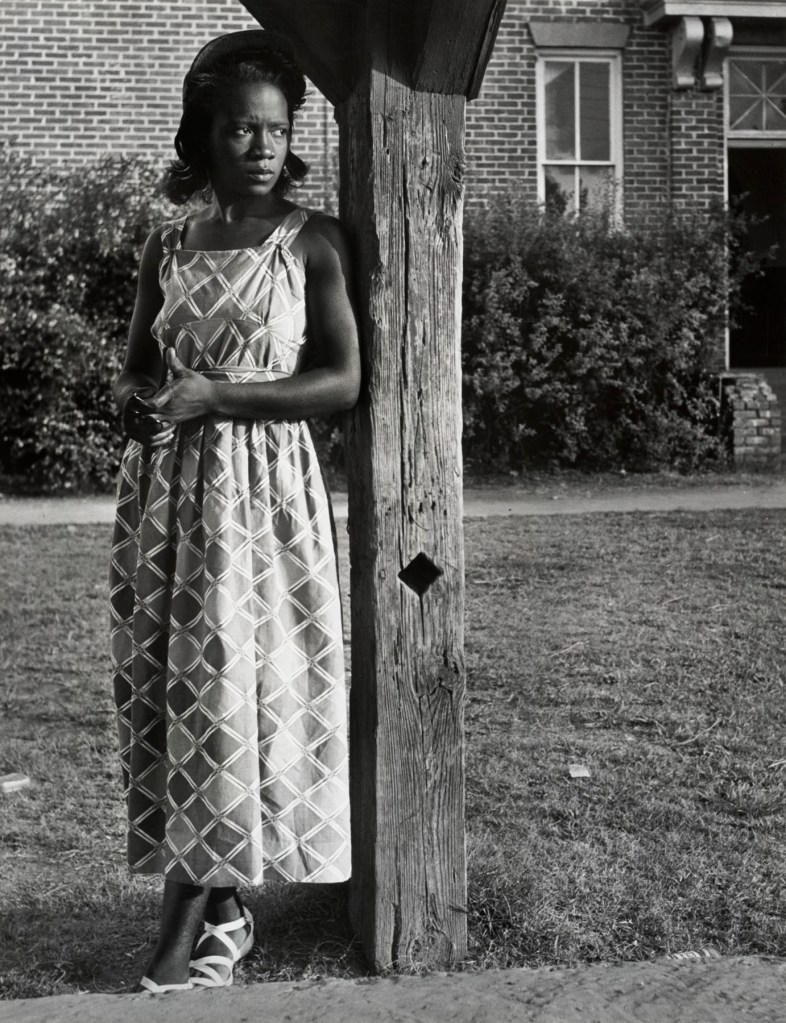

Cecil J. Williams (American, b. 1937)

During the summer of 1960, the elders of Orangeburg took to the streets as part of ongoing demonstrations and boycotts in support of civil rights. They are standing outside a segregated supermarket where they were allowed to shop but not sit down for lunch

1960, printed 2024

Inkjet print

37.3 x 55.9cm (14 11/16 x 22 in.)

Cecil J. Williams (American, b. 1937)

Cecil J. Williams (born November 26, 1937) is an American photographer, publisher, author and inventor who is best known for his photographs documenting the civil rights movement in South Carolina.

He began his career at an early age, photographing wedding and family parties. He studied art at Claflin University, while also being a photographer for the university. …

At the age of 14, Williams was one of 25 photographers around the world freelancing for JET magazine. JET caught wind of the movement growing in Orangeburg. They needed an onsite correspondent for constant updates, and someone to document the events. The only time Williams’ work appeared on the cover of JET was his picture of Coretta Scott King speaking at the protest during the 1969 Charleston hospital workers’ strike.

Williams has photographed significant desegregation efforts in South Carolina since the 1950s. Some of his most notable pictures are of the activity during the Briggs v. Elliott case in Summerton. It was the first of five desegregation cases pushing to integrate public schools in the United States. The five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case that declared that having “separate but equal” public schools for whites and blacks was unconstitutional.

Text from the Wikipedia website

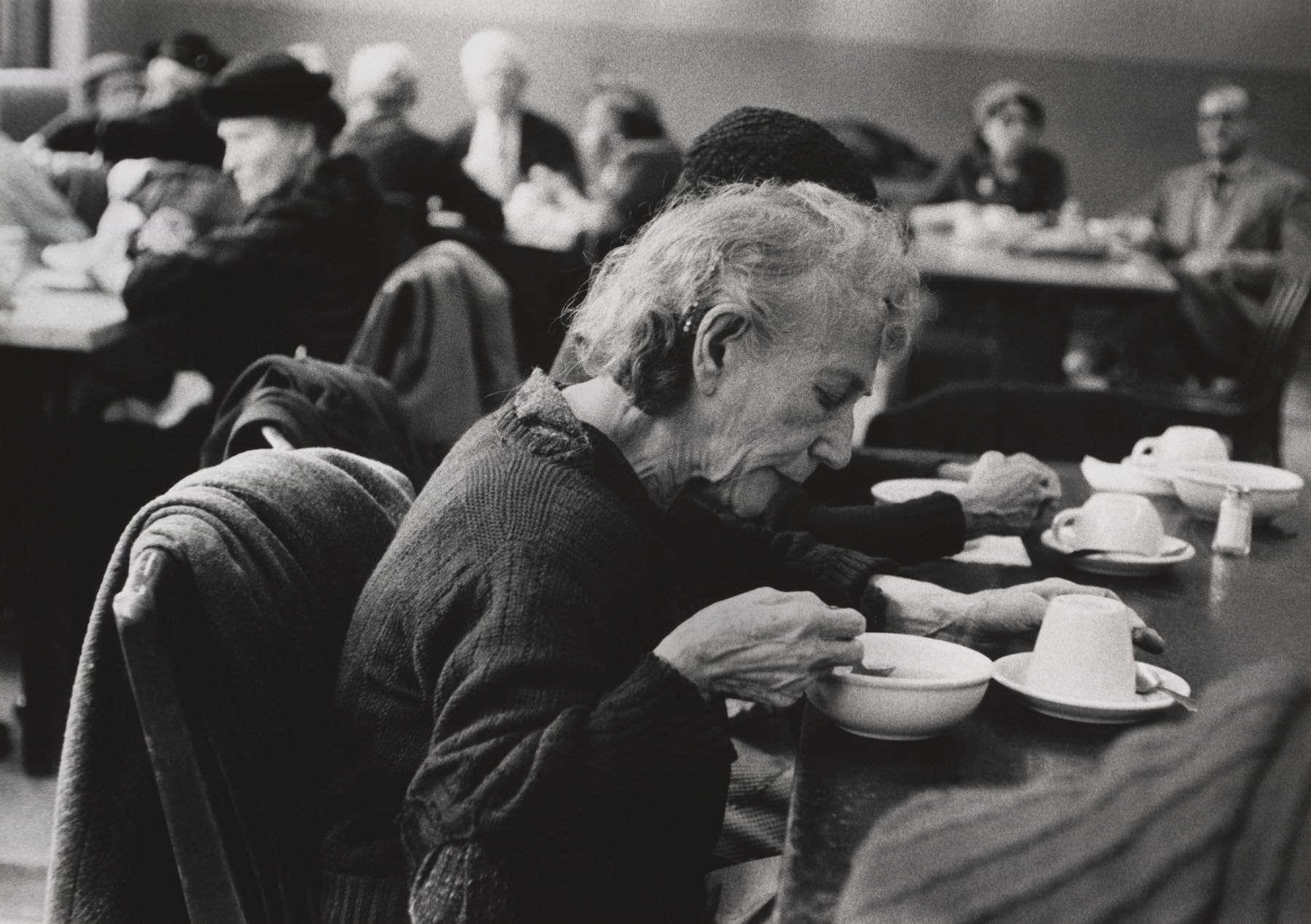

Cecil J. Williams (American, b. 1937)

Clara White Mission, Jacksonville, Florida

1960s, printed 2024

Inkjet print

45.7 x 45.7cm (18 x 18 in.)

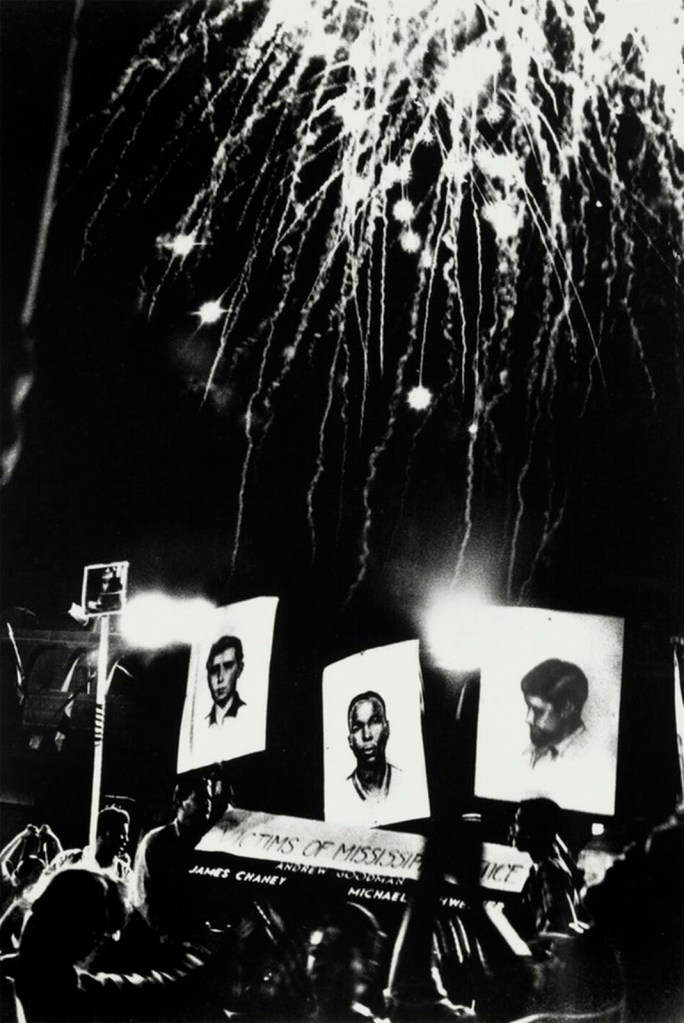

Bob Fletcher (American, b. 1938)

Placards of Goodman, Chaney, and Schwerner at a Demonstration on the boardwalk during the Democratic National Convention, Atlantic City, New Jersey

1964

Gelatin silver print

33.97 × 22.86cm (13 3/8 × 9 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Anonymous gift

Bob Fletcher (American, b. 1938)

Robert E. “Bob” Fletcher is a photographer, filmmaker, writer, and educator. Born in 1938 in Detroit, Michigan, Fletcher majored in History and English at Fisk University and Wayne State University. In 1963, Fletcher became active in the civil rights movement, taking photographs for and administering the National Student Association’s Detroit Tutorial Program. After moving to New York City, he worked at the Harlem Education Project and set up a photographic workshop.

In the summer of 1964, Fletcher became a Freedom School teacher in Mississippi and joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) staff as a photographer; he documented the Civil Rights Movement throughout the South, between 1964 and 1968. After returning to New York in 1969, Fletcher set up a photography workshop at the Henry Street Settlement, and taught photography at Antioch College and Brooklyn College Film Studio.

Text from the New York Public Library Archives & Manuscripts website

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Ethel Sharrieff in Chicago

1963

Gelatin silver print

14.6 × 15.9cm (5 3/4 × 6 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection)

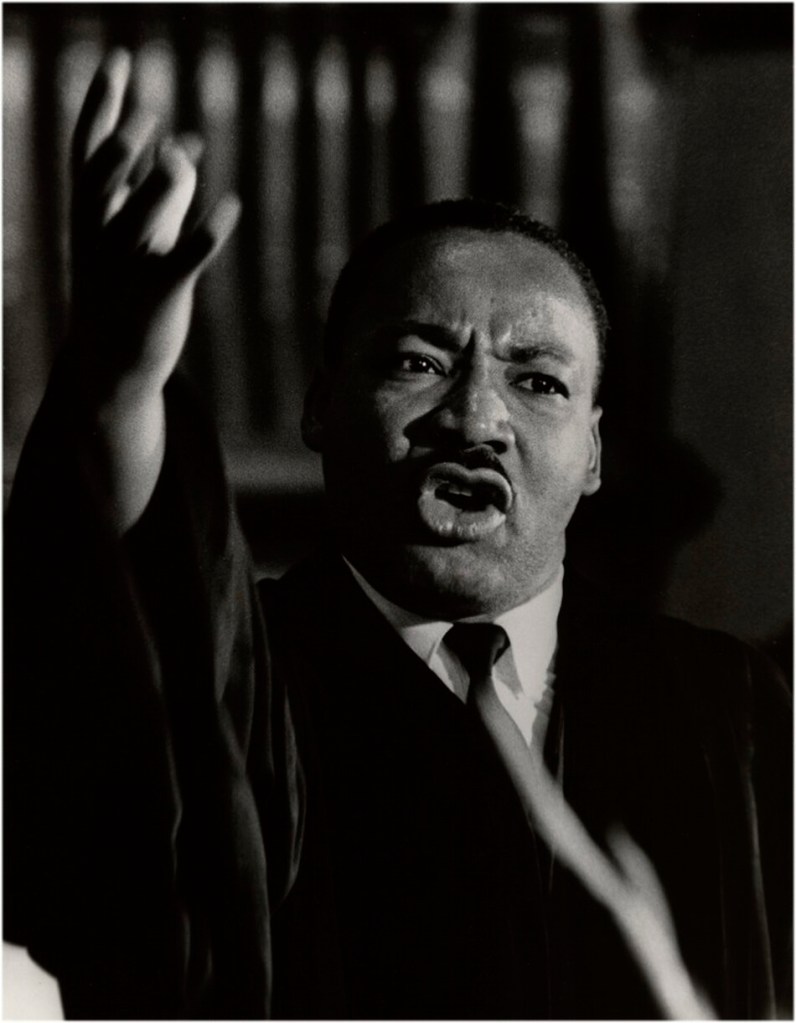

Robert A. Sengstacke (American, 1943-2017)

Dr. Martin Luther King

January 1, 1965

Gelatin silver print

35.1 × 27.3cm (13 13/16 × 10 3/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Robert A. Sengstacke (American, 1943-2017)

Robert A. “Bobby” Sengstacke spent more than a half century photographing Chicago’s cultural and political landscape, most notably for the weekly newspaper the Chicago Defender, for which he also worked as an editor. The Defender was founded by Robert’s great-uncle Robert Sengstacke Abbott in 1905, and Robert’s father, John Sengstacke, ran the paper for nearly 60 years. In the mid-1950s, after attending Florida’s Bethune Cookman College, Bobby Sengstacke returned to Chicago and honed his skills with fellow photographers Billy (Fundi) Abernathy, Le Mont Mac Lemore, and Bob Black. In the years that followed, he became a member of a tight-knit network of South Side photojournalists who created intimate documents of Chicago’s Black community, from Civil Rights rallies led by Martin Luther King Jr. to the city’s lively entertainment scene.

Sengstacke was also a founding member of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), which brought together Black artists, writers, intellectuals, and activists on Chicago’s South Side.

Text from The Art Institute of Chicago website

Doris A. Derby (American, 1939-2022)

Member of Southern Media Photographing a Young Girl, Farish Street, Jackson, Mississippi

1968

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of David Knaus

Doris A. Derby (American, 1939-2022)

The photography of the US civil rights activist and academic Doris Derby … began through documenting the struggles of black people in the segregated south. However, rather than recording the dramatic events and protests of the nine years from her arrival in Mississippi from New York in 1963, Doris chose to capture the everyday human effort required to live through them.

She went into rural communities to witness the work of children in the fields and women living in wooden shacks trying to care for families. “They were looking to find some help, some way to get out of their horrible poverty and despair,” she said. …

Influenced both by the German expressionist artist Käthe Kollwitz, who was concerned with the effects of poverty, hunger and war on the working class, and the photographer Roy DeCarava, who captured the creativity of the Harlem Renaissance, she also took pictures of children in urban settings, of old and young people attending election events, and those working for the movement, among them the author Alice Walker.

Hannah Collins. “Doris Derby obituary,” on The Guardian website Wed 13 Apr 2022 [Online] Cited 26/11/2025

Darryl Cowherd (American, b. 1940)

Stokely Carmichael, Unknown Chicago Church

c. 1968

Gelatin silver print

24.8 × 15.5cm (9 3/4 × 6 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

A key figure in Chicago’s Black Arts Movement, Darryl Cowherd has enjoyed an extensive career ranging from photojournalism to broadcast television. At the age of 20, frustrated with work and school, Cowherd followed the advice of his mentor, Chicago-based photographer Robert Earl Wilson, who encouraged him to travel and photograph abroad. Cowherd had initially studied to become a doctor and then worked for the postal service, but neither role proved a lasting fit. After nearly four years in Europe, during which Cowherd honed his photography skills, he returned to Chicago in 1964 and began taking freelance photography assignments while working at a film processing lab. His return to Chicago coincided with the emergence of the Chicago Freedom Movement (1965-67) and the Black Arts Movement (most active in the years 1965-76). An active participant in both movements, Cowherd frequently photographed the activities surrounding them as they grew and gained momentum.

Cowherd was a founding member of the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC), a collective that brought together Black artists, writers, intellectuals, and activists on Chicago’s South Side.

Text from The Art Institute of Chicago website

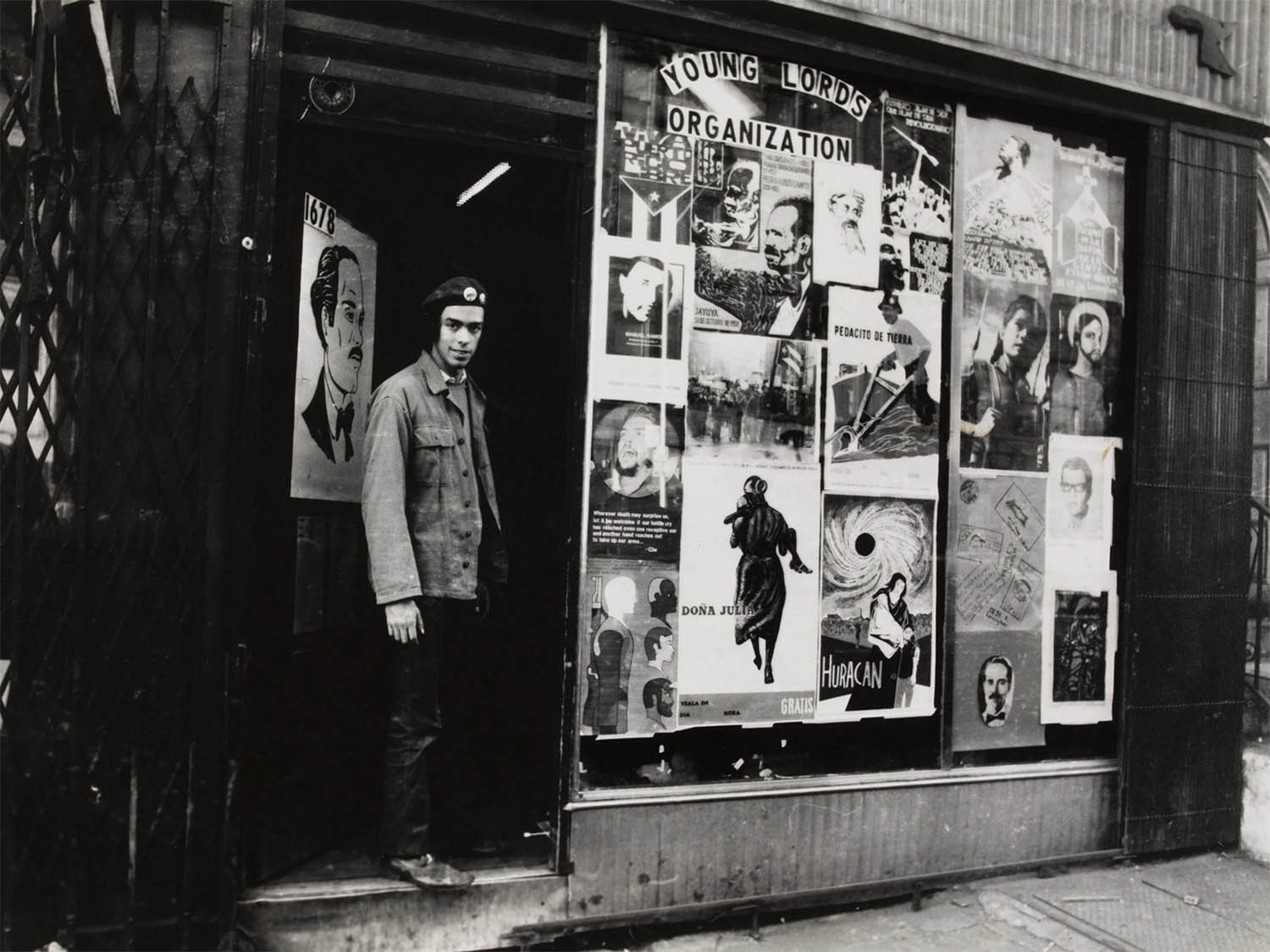

Hiram Maristany (American, 1945-2022)

Juan González, Minister of Information, in the doorway of the first office of the Young Lords

1969, printed 2021

Gelatin silver print

33 x 46cm (13 x 18 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Hiram Maristany

Hiram Sebastian Maristany was a Nuyorican American photographer, and director of El Museo del Barrio (a museum in NYC which specialises in Latin American and Caribbean art, with an emphasis on works from Puerto Rico and the Puerto Rican community in New York City) from 1975 to 1977. He was known for his association with, and documentation of, the Young Lords chapter in Harlem, which he co-founded in 1969.

Juan González was a co-founder of the Young Lords, a radical Puerto Rican rights organisation in New York City, where he helped lead the group in protests for social justice. The Young Lords fought for better healthcare, education, and city services, and against police abuse and Puerto Rico’s colonial status. Following his work with the Young Lords, González became a celebrated journalist, co-hosting Democracy Now! and writing for the New York Daily News.

Texts from the Wikipedia website

What Is the Black Arts Movement? Seven Things to Know

Poet Larry Neal, who coined the term Black Arts Movement, described it as “a cultural revolution in art and ideas.” This movement included poets, playwrights, musicians, filmmakers, photographers, and painters. They came together to make art that advanced civil rights and celebrated Black history, identity, and beauty.

This cultural revolution shook up the art world in the 1950s and ’60s. It embodied the struggle for self-determination championed by global freedom movements. New collectives, workshops, and collaborations emerged. Creatives made art that promoted Black dignity, hope, and freedom. They asked, how could art inspire social and political change? And what would it look like?

Photography was a driving force from the beginning, playing a critical role as both a communications tool and art form. Learn more about the movement and photography’s part in it – major themes in our exhibition Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955-1985.

1/ Its origins are in the civil rights movement

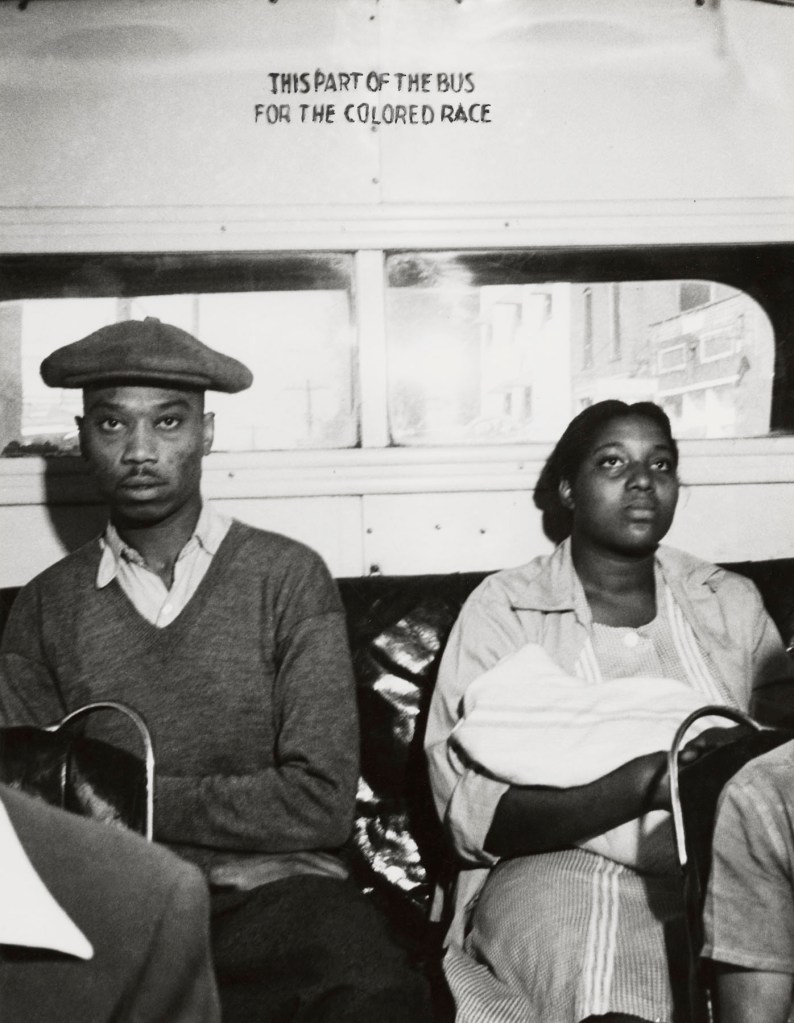

Our exhibition begins in 1955, more than a decade before Larry Neal named the Black Arts Movement. That year, several events – and photographs of those events – helped catalyse the civil rights movement.

In September, Jet magazine was one of several publications that printed open-casket photographs of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago who was lynched in Mississippi. Those disturbing images were seen across the country, including by a woman in Montgomery, Alabama: Rosa Parks. That December, Parks sat in the front, “white only” section of a segregated bus. The driver demanded that she give up her seat to a white passenger. She refused. As she later recounted, Emmett Till was on her mind in that moment.

Parks, in turn, was photographed sitting at the front of the segregated bus. Those images, and others like them, brought widespread awareness to the struggles for equal rights. Organisations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) encouraged photography of their marches, demonstrations, and acts of nonviolent civil disobedience. SNCC even taught some members to use a camera. Lifelong activist Maria Varela became a SNCC photographer after recognising the need for more images of Black life to support the movement.

2/ Poets, writers, and playwrights led the movement

The beginning of the Black Arts Movement is often pinned to poet, playwright, and writer Amiri Baraka founding the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School in New York City’s Harlem neighbourhood in 1965. Nikki Giovanni, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Audre Lorde were among the many writers and poets active in the movement. Some collaborated with visual artists, even forming collectives such as the Organization of Black American Culture (OBAC) in Chicago.

OBAC writers, scholars, painters, and photographers collaborated to create the Wall of Respect community mural in 1967. It commemorated key figures in African American history, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Muhammad Ali, and Nina Simone. The mural was like a two-story collage that covered the facade of a building in the city’s South Side neighbourhood. It incorporated paintings by several artists alongside mounted photographs by Roy Lewis and Darryl Cowherd. At the centre was Amiri Baraka’s poem “SOS,” which opens, “Calling all black people.” The mural was demolished in 1972, but photographs by Roy Lewis and Robert Sengstacke continue to spread its message.

3/ It was inspired by jazz

Music was an equally important part of the Black Arts Movement. Musicians John Coltrane and Sun Ra both performed at a fundraiser for Amiri Baraka’s Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School. Their experimental and expressive jazz inspired Black Arts Movement writers and artists.

In Coltrane at the Gate, photographer Adger Cowans depicted the saxophonist’s energy. Ming Smith captured the magic of a Sun Ra performance. For his homage to saxophonist Charlie Parker (who was commonly known as “Bird”), painter Raymond Saunders embraced the spontaneous spirit of jazz. Saunders collaged a newsprint photograph below the word “bird” written in a chalk-like white script.

4/ It celebrated Black beauty

The Black Arts Movement celebrated the “beauty and goodness of being Black,” as Larry Neal put it. Photographer Kwame Brathwaite helped popularise the phrase “Black is beautiful.” Brathwaite was a pioneer of uplifting Black identity. He helped found groups that challenged conventional standards of beauty and celebrated African heritage. They organised fashion shows, created “Black is beautiful” products, and operated a photography studio.

In Untitled (Portrait, Reels as Necklace), Brathwaite adorned the model with a necklace made from film developing reels to “expose” her beauty. More than a decade later, Carla Williams created a self-portrait that echoed Brathwaite’s work. Showing herself in curlers, Williams challenged popular notions of beauty.

5/ It brought artists together

Small collectives of visual artists and photographers came together around the principles of the Black Arts Movement. In New York, the Kamoinge Workshop photography collective met regularly to critique each other’s work, debate photography’s purpose and aesthetics, and share tips. They created a space for their art by developing their own portfolios and exhibitions. The workshop also produced the groundbreaking Black Photographers Annual between 1973 and 1980.

A group of Chicago artists formed AfriCOBRA. The collective’s founders defined their own aesthetic principles, aimed at creating “images that jar the senses and cause movement” and “images designed for mass production.”

6/ It spread across the Atlantic

The Black Arts Movement made an impact beyond the United States. In Great Britain, Raphael Albert organised and photographed Black beauty pageants in London. James Barnor focused on style, migration, and Black city life in London and in Accra, Ghana. Horace Ové photographed the British Black Power Movement. He also captured scenes of the West African and West Indian communities in London, like his Walking Proud, Notting Hill Carnival.

Samuel Fosso opened his first photography studio in Bangui, Central African Republic, at age 13. After finishing with clients, Fosso would use his studio to experiment with self-portraits. He wore an array of costumes and adopted personas, often taking inspiration from the pictures of Black Americans he saw in magazines shared by American Peace Corps volunteers.

7/ It influenced generations of artists

By the end of the 1970s, the literary arm of the Black Arts Movement had waned, but a new generation of artists and photographers carried on its spirit. Coming out of art school, photographers such as Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson explored more personal, metaphorical, and conceptual ideas.

In her Family Pictures and Stories series, Weems made her own family the subjects. The intimate photographs presented a counterargument to claims that many Black Americans faced poverty and struggle as a result of weak family structures. Weems paired the photographs with brief stories about each family member.

Text from the National Gallery of Art website

Herbert Randall (American, b. 1936)

Untitled (Bed-Stuy, New York)

c. 1960s

Gelatin silver print

22.8 x 15.6cm (9 x 6 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, 2022.89.1

© Herbert Randall

Herbert Randall (American, b. 1936)

Herbert Eugene Randall, Jr. is an American photographer who had documented the effects of the Civil Rights Movement. Randall is of Shinnecock, African-American and West Indian ancestry.

Randall studied photography under Harold Feinstein in 1957. From 1958 to 1966, he worked as a freelance photographer for various media organizations. His photographs were used by the Associated Press, United Press International, Black Star, various television stations, and other American and foreign publications. Randall was also a founding member of the Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of African-American photographers, in New York City in 1963.

In 1964, Sanford R. Leigh, the Director of Mississippi Freedom Summer’s Hattiesburg project, persuaded Randall to photograph the effects of the Civil Rights Movement in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Randall had a Whitney Fellowship for that year, and had been looking for a project. He spent the entire summer photographing solely in Hattiesburg, among the African-American community and among the volunteers in area projects such as the Freedom Schools, Voter Registration, and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party campaign.

Only five of Randall’s photographs were published in the summer of 1964. One seen worldwide was the bloodied, concussed Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld, head of a prominent Cleveland congregation and former conscientious objector to World War II. However, most of his photographs sat in a file at the Shinnecock Reservation, on Long Island, New York.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Billy Abernathy (Fundi) (American, 1939-2016)

Mother’s Day from the series “Born Hip”

1962

gelatin silver print

17.5 x 13.3cm (6 7/8 x 5 1/4 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of the Illinois Arts Council

Photo: The Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY

Billy Abernathy (Fundi) (American, 1939-2016)

Photographer Billy (Fundi) Abernathy was known for creating images that defined Black confidence, elegance, and style. This work extended to his collaborations with his wife, Sylvia (Laini) Abernathy, with whom he designed album covers for Delmark Records in the 1960s. Around that time, the poet and author Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) encountered Abernathy’s photographs of Chicago and proposed a book project that would combine his poetry with Abernathy’s images. The resulting collaboration, In Our Terribleness (Some Elements and Meaning in Black Style), was designed by Laini and published in 1970. In 1971 the New York Times hailed the book as “an example of the new direction that black art is taking.”

Text from The Art Institute of Chicago website

Charles “Teenie” Harris (American, 1908-1998)

A television playing coverage of James Baldwin at the March for Freedom and Jobs in Washington, DC

1963/2025

Gelatin silver print

National Gallery of Art, Washington

African American artist Charles “Teenie” Harris, captured “the essence of daily African-American life in the 20th century. For more than 40 years, Harris – as lead photographer of the influential Pittsburgh Courier newspaper – took almost 80,000 pictures of people from all walks: presidents, housewives, sports stars, babies, civil rights leaders and even cross-dressing drag queens.”

See the Art Blart posting on the exhibition Teenie Harris, Photographer: An American Story at Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, October 2011 – April 2012

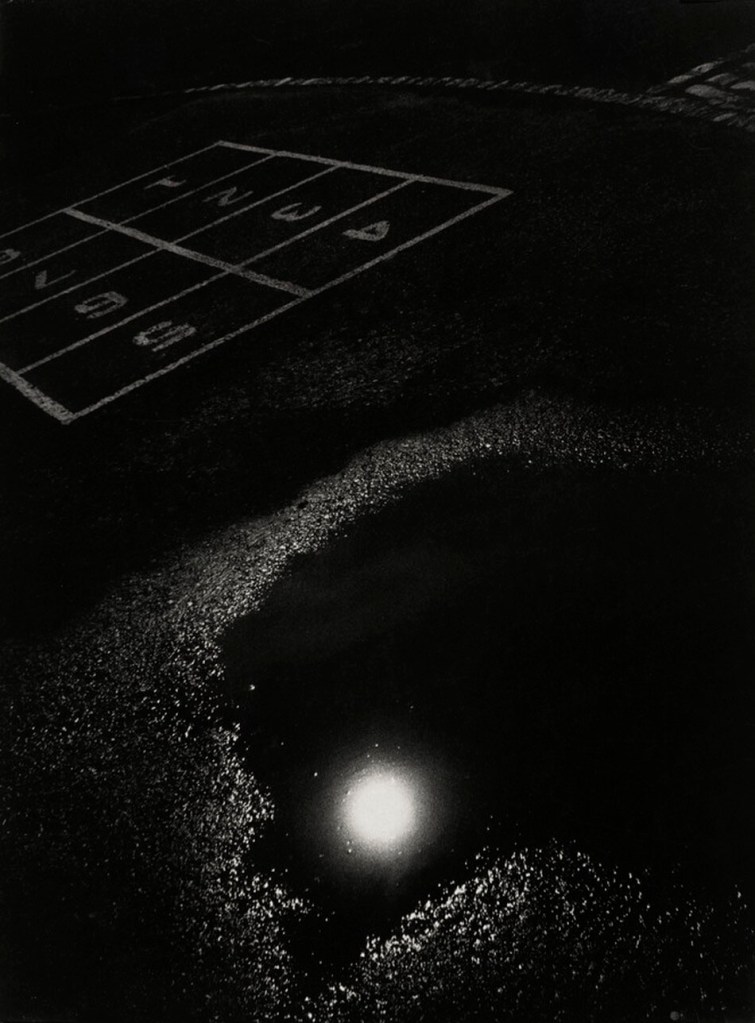

Louis Draper (American, 1935-2002)

Untitled (Playground) from the “Playground Series”

c. 1965

Gelatin silver print

25.7 x 19.1cm (10 1/8 x 7 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Draper Preservation Trust, Nell D. Winston, Trustee

Louis Draper (American, 1935-2002)

In 1953, he enrolled at the historically Black college in Petersburg, which was not far from his hometown of Richmond. He began working as a reporter for the school paper, and during that time Draper’s father, who was an amateur photographer himself, sent Louis his first camera. By 1956, Draper’s title at the paper had changed to cameraman. After his revelatory first experience with The Family of Man, a catalogue that accompanied the 1955 photography exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art, he decided to leave school during his final semester and move to New York City to become a photographer. Once there, Draper enrolled in a photography workshop led by Harold Feinstein, and was mentored by W. Eugene Smith, one of the most prominent American photojournalists.

In 1963, the same year as the March on Washington, Draper became a founding member of the Kamoinge Workshop, a New York-based collective of Black photographers. Workshop members met regularly to discuss one another’s work, produced group portfolios, exhibitions, and publications, and mentored young people all over the city. Draper emerged as one of the group’s teachers, which began his long career as an educator (he worked in numerous teaching roles, including at Pratt Institute and Mercer County Community College). The collective aimed to “create the kind of images of our communities that spoke of the truth we’d witnessed and that countered the untruths we’d all seen in mainline publications.” Kamoinge members wanted to avoid the racial stereotypes prevalent in the media and the violence that was typical of journalistic coverage of the Civil Rights Movement, working instead to represent their communities in a positive light.

Jane Pierce, Carl Jacobs Foundation Research Assistant, Department of Photography, “Louis Draper,” on the MoMA website 2021 [Online] Cited 27/11/2025

Louis Draper (American, 1935-2002)

Untitled (Santos) from the “Playground Series”

1967

Gelatin silver print

32.9 x 22.8cm (12 15/16 x 9 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

© Draper Preservation Trust, Nell D. Winston, Trustee

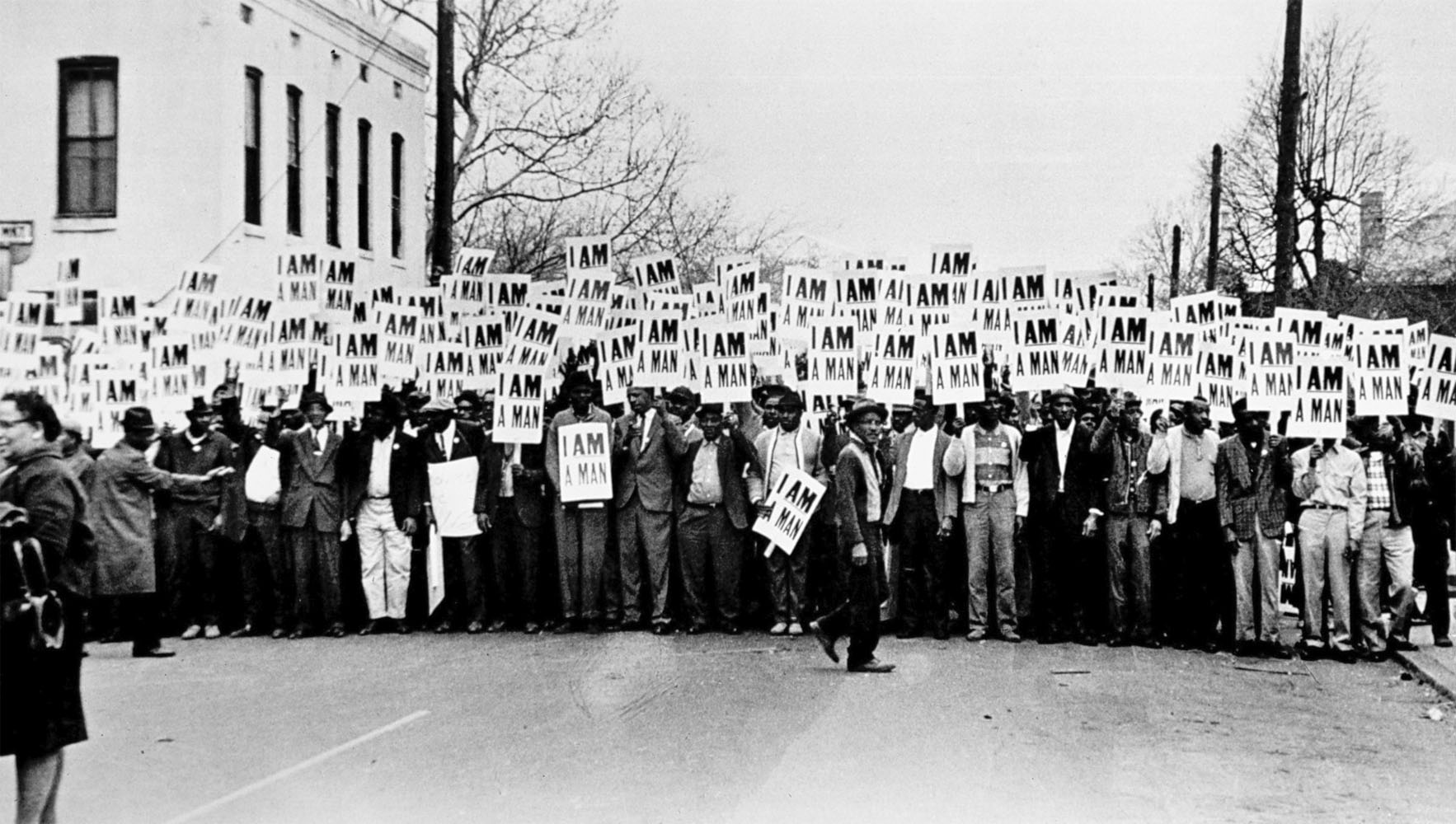

Ernest C. Withers (American, 1922-2007)

I Am A Man, Sanitation Workers Strike, Memphis, Tennessee

March 28, 1968

Gelatin silver print

19 × 32.6cm (7 1/2 × 12 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Ernest C. Withers (American, 1922-2007)

Photojournalist Ernest C. Withers was born on August 7, 1922, in Memphis, Tennessee. Withers got his start as a military photographer while serving in the South Pacific during World War II. Upon returning to a segregated Memphis after the war, Withers chose photography as his profession.

In the 1950s, Withers helped spur the movement for equal rights with a self-published photo pamphlet on the Emmitt Till murder. Over the next two decades, Withers formed close personal relationships with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, and James Meredith. Withers’s pictures of key civil rights events from the Montgomery Bus Boycott to the strike of Memphis sanitation workers are historic. Indeed, Withers was often the only photographer to record these scenes, many of which were not yet of interest to the mainstream press.

Withers photographed more than the southern Civil Rights Movement. Whether Jackie Robinson, Willie Mays, and other Negro League baseball players, or those jazz and blues musicians who frequented Memphis’ Beale Street, Withers photographed the famous and not-so famous. Withers’s collection includes pictures of early performances of Elvis Presley, B.B. King, Ike and Tina Turner, Ray Charles, and Aretha Franklin.

Text from The History Makers website

Louis Draper (American, 1935-2002)

Fannie Lou Hamer, Mississippi

July 1971

Gelatin silver print

21.5 x 29.2cm (8 7/16 x 11 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Draper Preservation Trust, Nell D. Winston, Trustee

First-of-Its-Kind Exhibition Opening at the National Gallery of Art Explores Photography’s Role in the Black Arts Movement

Never-before-seen photographs alongside images of cultural icons reveal the medium’s central role during a pivotal era of creative expression

The National Gallery of Art presents Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955-1985, an exhibition exploring the work of American and Afro-Atlantic diaspora photographers in developing and fostering a distinctly Black visual culture and identity. The first presentation to investigate photography’s role in the Black Arts Movement, a creative initiative comparable to the Harlem Renaissance in its scope and impact, which evolved concurrently to the civil rights and international freedom movements, the exhibition reveals how artists developed strategies to engage communities and encourage self-representation in media, laying a foundation for socially engaged art practices that continue today. Photography and the Black Arts Movement will be on view in the West Building from September 21, 2025, to January 11, 2026, before traveling to California and Mississippi.

Photography and the Black Arts Movement brings together approximately 150 works spanning photography, video, collage, painting, installation, and other photo-based media, some of which have rarely or never been on view. Among the over 100 artists included in the exhibition are Billy Abernathy (Fundi), Romare Bearden, Dawoud Bey, Frank Bowling, Kwame Brathwaite, Roy DeCarava, Louis Draper, David C. Driskell, Charles Gaines, James E. Hinton, Danny Lyon, Gordon Parks, Adrian Piper, Nellie Mae Rowe, Betye Saar, Raymond Saunders, Jamel Shabazz, Lorna Simpson, and Carrie Mae Weems.

This expansive selection of work showcases the broad cultural exchange between writers, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, and other visual artists of many backgrounds, who came together during the turbulent decades of the mid-20th century to grapple with social and political changes, the pursuit of civil rights, and the emergence of the Pan-African movement through art. The exhibition also includes art from Africa, the Caribbean, and Great Britain to contextualize the global engagement with the social, political, and cultural ideas that propelled the Black Arts Movement.

“Working on many fronts – literature, poetry, jazz and new music, painting, sculpture, performance, film, and photography – African American artists associated with the Black Arts Movement expressed and exchanged their ideas through publications, organisations, museums, galleries, community centres, theatres, murals, street art, and emerging academic programs. While focusing on African American photography in the United States, the exhibition also includes works by artists from many communities to consider the extensive interchange between North American artists and the African diaspora. The exhibition looks at the important connections between America’s focus on civil rights and the emerging cultural movements that enriched the dialog,” said Philip Brookman, cocurator of the exhibition and consulting curator of the department of photographs at the National Gallery of Art.

“Photography and photographic images were crucial in defining and giving expression to the Black Arts Movement and the civil rights movement. By merging the social concerns and aesthetics of the period, Black artists and photographers were defining a Black aesthetic while expanding conversations around community building and public history,” said Deborah Willis, guest cocurator, university professor and chair of the department of photography and imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts and founding director of the Center for Black Visual Culture at New York University. “The artists and their subjects helped to preserve compelling visual responses to this turbulent time and their images reflect their pride and determination.”

About the Exhibition

The exhibition draws significantly from the National Gallery’s collection – including more than 50 newly acquired works by Dawoud Bey, Kwame Brathwaite, Louis Draper, Ray Francis, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, Horace Ové, Jamel Shabazz, Malik Sidibé, Ming Smith, and Carrie Mae Weems, among others – and from lenders in the US, Great Britain, and Canada. Photography and the Black Arts Movement, 1955–1985 presents the cultural and political titans of the era, including civil rights leaders, artists, and musicians, as well as everyday people, scenes of daily life, and fashion and commercial photography. Structured around nine thematic sections – including explorations of the self, community, fashion and beauty, the media, and ritual – the exhibition weaves a holistic vision of the period and its cultural impact.

Among the works in the first section of the exhibition is a collage by Romare Bearden, 110th Street Harlem Blues (1972). A dynamic mixture of painted paper and photographs, the work illustrates the ongoing vitality of Harlem’s community, echoing the vibrancy and social content of the Harlem Renaissance, which Bearden was exposed to in his early life. Moving into the section titled Picturing the Self / Picturing the Movement, self-portraits by Coreen Simpson, Alex Harsley, and Barkley L. Hendricks underscore a central theme of the exhibition: artists asserting their presence within the broader narrative of the movement and the era, along with the importance of self-representation in their art. A highlight of Representing the Community – a section filled with everyday scenes of people at work and at rest – is Ralph Arnold’s Soul Box (1969), a mixed-media assemblage of found objects and collage, serving as a time capsule that captures stories of the Black Arts Movement.

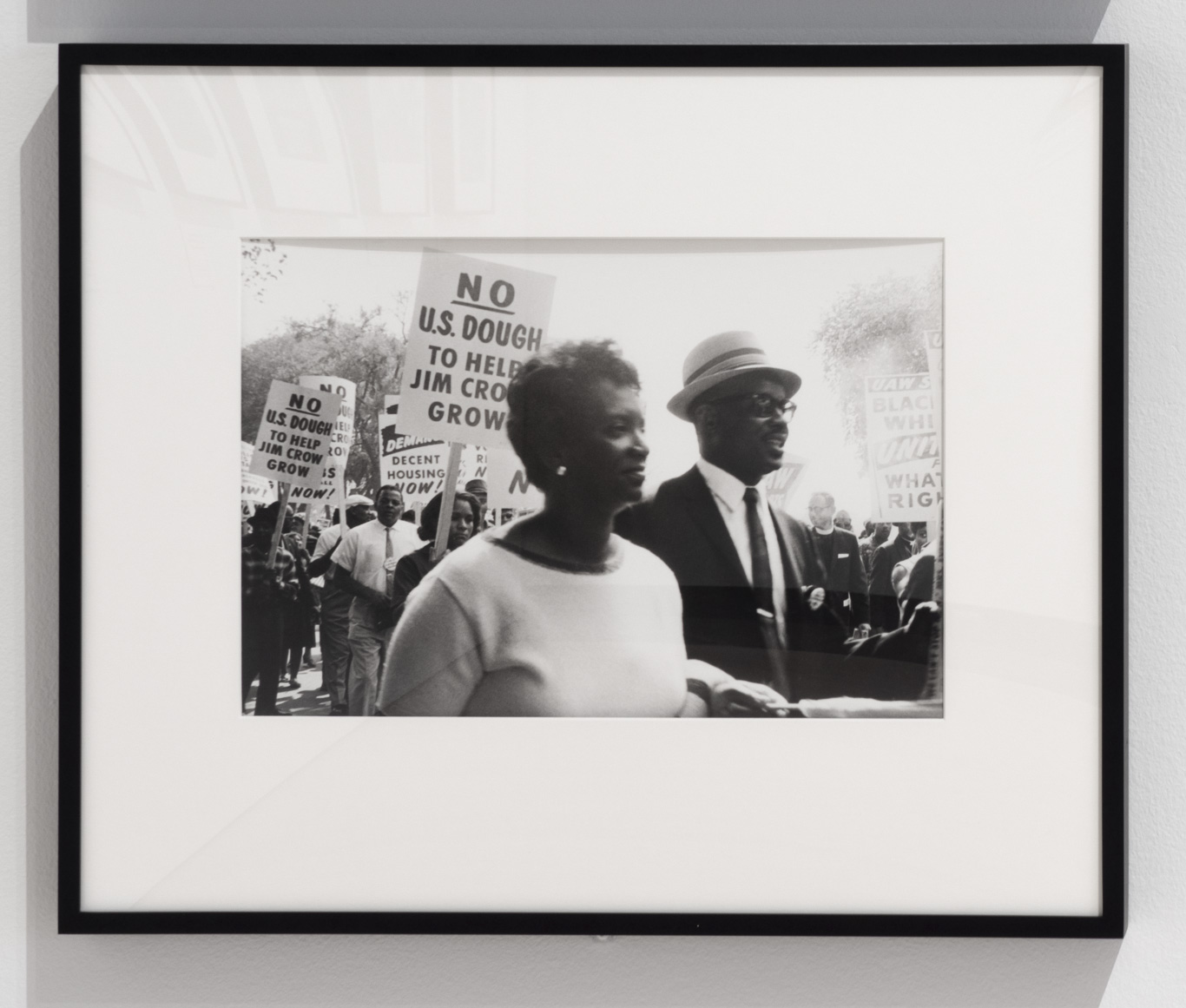

Photographs were a crucial tool used to communicate the events of the civil rights movement to a national audience. Artists and news media understood the power of photographs to address inequality and advocate for civil and human rights, and some works in the exhibition are by photojournalists who captured the speeches, marches, and sit-ins that defined the era. A rarely seen 1965 photograph by Frank Dandridge captures Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. watching President Lyndon B. Johnson’s televised address following the Selma, Alabama, marches – events that would ultimately lead to the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Depicting Dr. King in a private, domestic moment, the image underscores not just the personal gravity of the moment but the television’s growing role in shaping public understanding of the era’s historic events. One of several works featured in the In the News section, it reflects how photographers responded to the shifting landscape of news media – from still photography to the rise of television.

The Black Arts Movement was instrumental in reshaping fashion, advertising, and media as tools of self-representation and cultural empowerment. A Kraft Foods advertisement (1977), photographed by Barbara DuMetz and featuring a young Black girl holding her doll, illustrates how the movement prompted advertisers to engage Black audiences more thoughtfully by hiring Black photographers and models in their campaigns. It is among the highlights of the Fashioning the Self section, along with an editorial photograph by Kwame Brathwaite, the photographer who helped coin the “Black is Beautiful” movement, and many depictions of women in beauty shops, showing the importance of these spaces to forming identity and community.

The exhibition’s concluding section, Transformations in Art and Culture, reflects a shift in the Black Arts Movement’s purpose – from its earlier focus on civil rights to a younger generation’s engagement with more historical and conceptual ideas, while still drawing on the movement’s visual language. Highlights include multimedia and time-based works by Ulysses Jenkins, Charles Gaines, and Lorna Simpson, which explore new and experimental ways to explore Black identity.

Exhibition Publication

Published in association with Yale University Press, the fully illustrated catalog accompanying the exhibition examines the vital role photography played in the evolution of the Black Arts Movement, which brought together writers, filmmakers, and artists as they explored ways of using art to advance civil rights and Black self-determination. Edited by Philip Brookman and Deborah Willis, with a preface by Angela Y. Davis and contributions by Makeda Best, Margo Natalie Crawford, Romi Crawford, Cheryl Finley, Sarah Lewis, and Audrey Sands, this book reveals how photographs operated across art, community building, journalism, and political messaging to contribute to the development of a distinctly Black art and culture. Essays by these distinguished scholars focus on topics such as women and the movement, community, activism, and Black photojournalism, and consider the complex connections between American artists and the African diaspora, and the dynamic interchange of Pan-African ideas that propelled the movement.

Press release from the National Gallery of Art

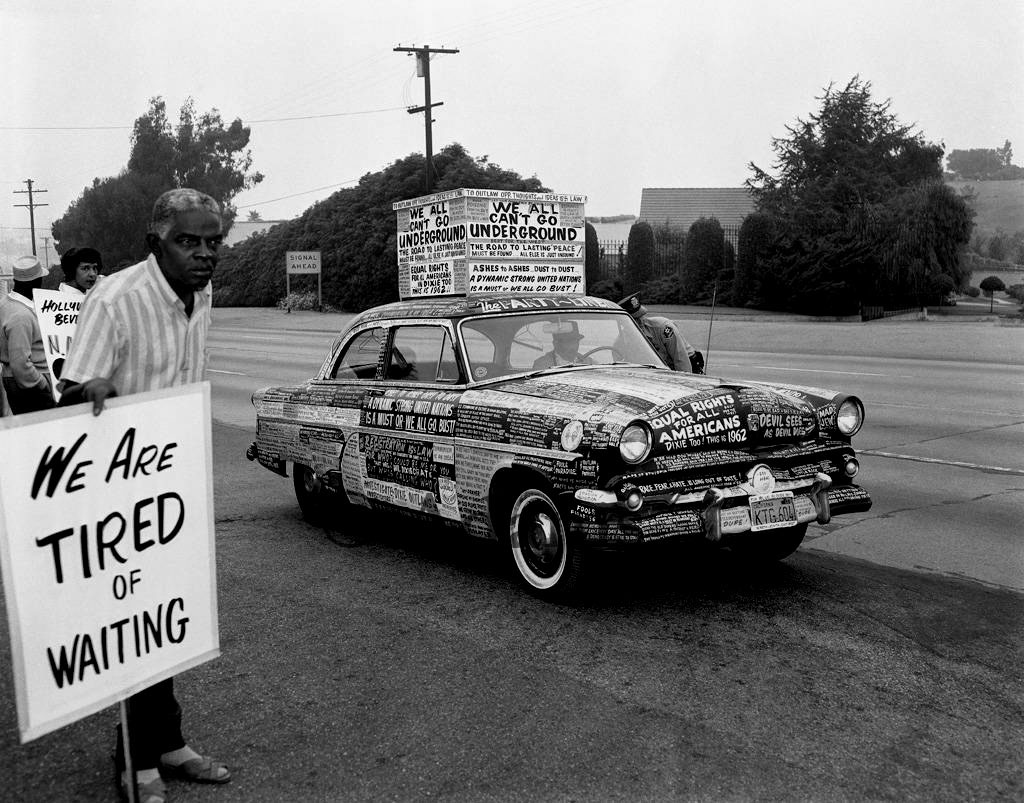

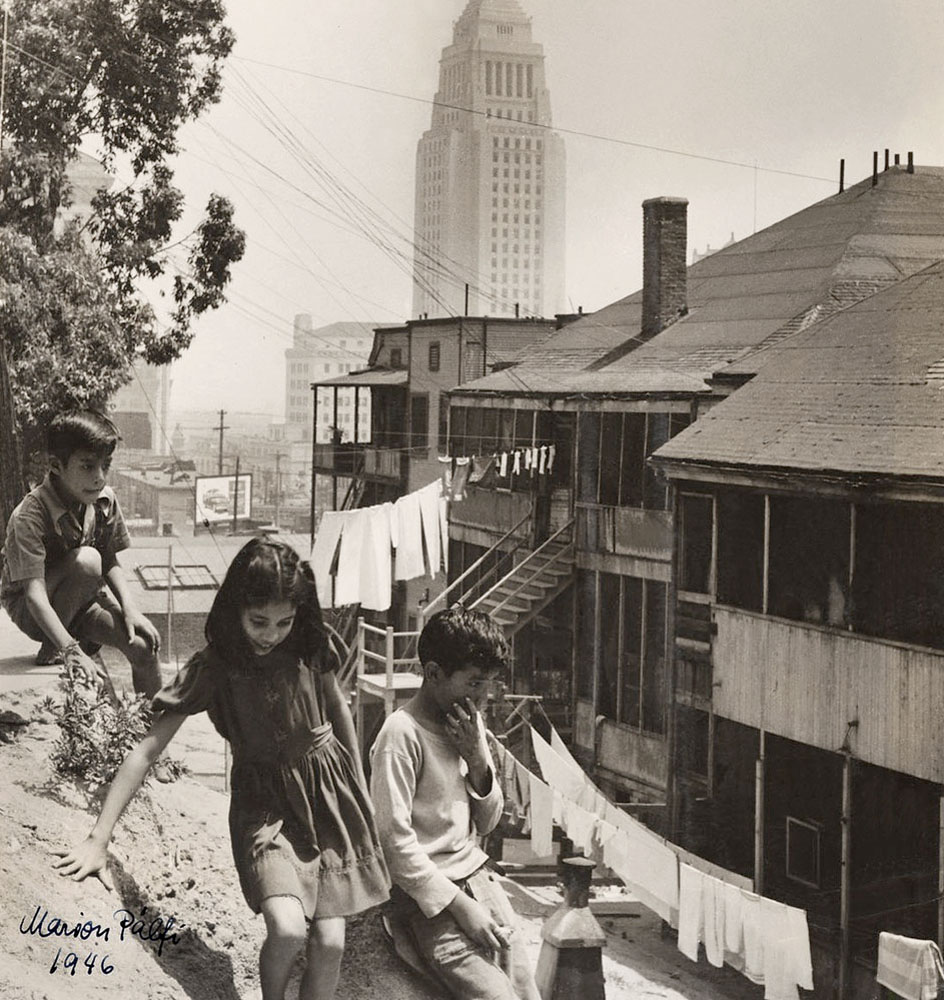

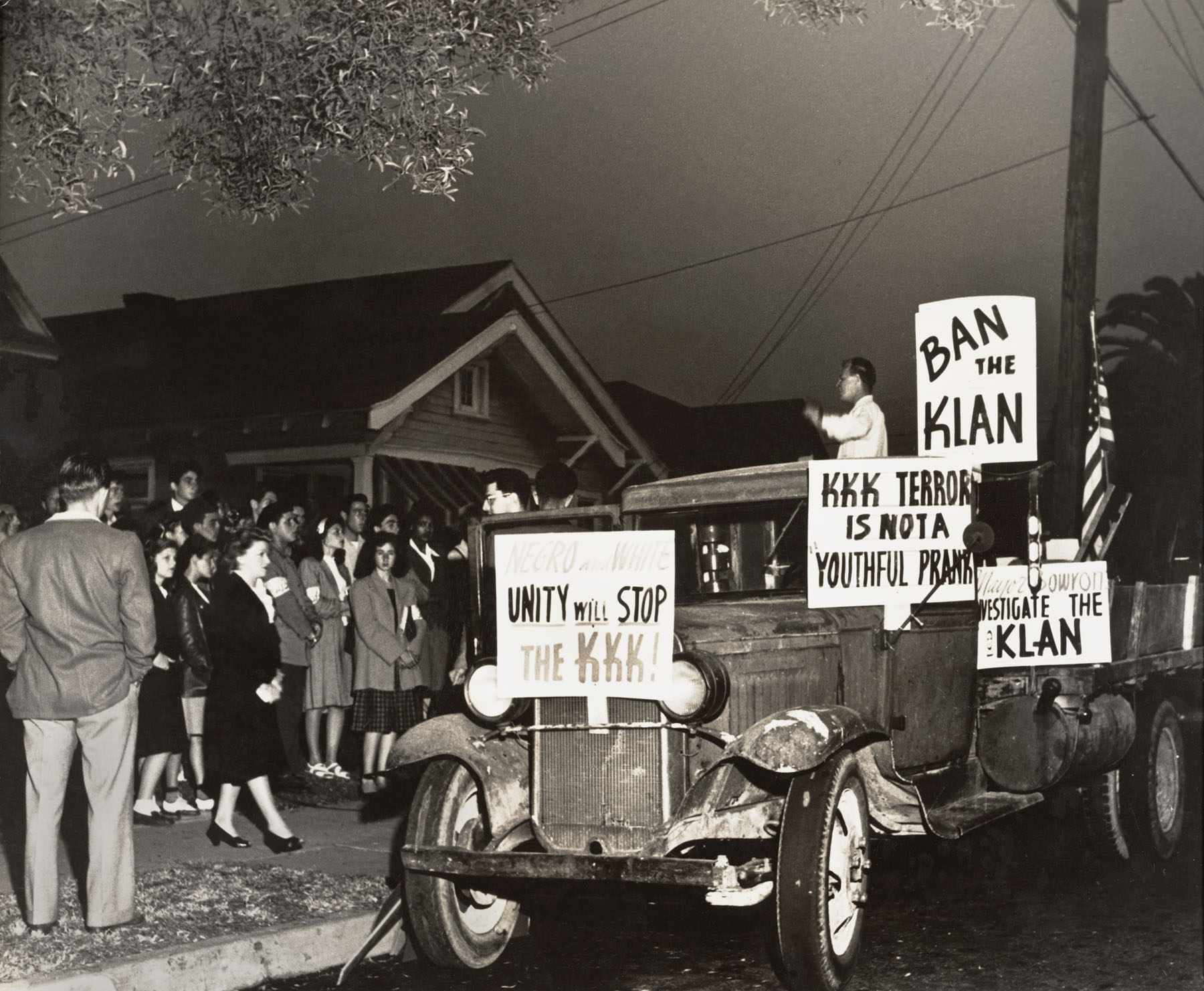

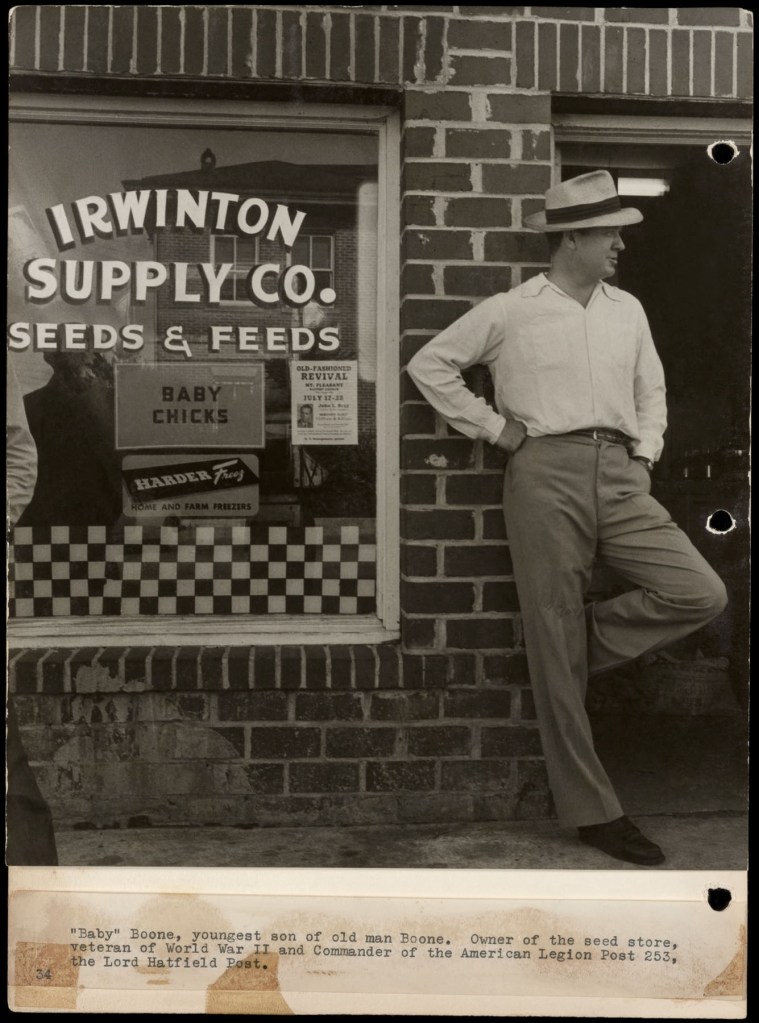

Harry Adams (American, 1918-1985)

Protest Car, Los Angeles

1962, printed 2024

Inkjet print

27.5 x 35.4 cm (11 x 13 15/16 in.)

Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge, Harry Adams Archive

© Harry Adams. All rights reserved and protected.

Courtesy of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center at California State University, Northridge

Harry Adams (American, 1918-1985)

Harry Adams, also known as “One Shot Harry,” was one of the best-known members of the Los Angeles African American community. Having access to the city’s inner circle, he became known for his images of politicians, entertainers, and society figures. Adams worked as a freelancer for the California Eagle and Los Angeles Sentinel for 35 years and had a number of churches and lawyers as clients. His collection is particularly rich in its documentation of African American social life including images of social organisations, churches, schools, civil rights organisations, protests and cultural events. …

The collection of images for the period 1950-1985 is rich in its depiction of the unique lives of African Americans in and around the Los Angeles area. There are many images of important black political leaders, such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Malcolm X, and many others.

Text from the California State University Northridge website

Raphael Albert (British born Grenada, 1939-2009)

Beauty Salon, London

c. 1960s

Gelatin silver print

27.3 x 27.3cm (10 3/4 x 10 3/4 in.)

Collection of Autograph, London

© Raphael Albert

Between the late 1960s and the early 1990s, the cultural promoter, entrepreneur and photographer Raphael Albert organised and documented numerous black beauty pageants and other cultural events in London. His long and successful career as a promoter and chronicler of pageants included the establishment of Miss Black and Beautiful, Miss West Indies in Great Britain, and Miss Grenada.

These competitions celebrated the global ‘Black is Beautiful’ aesthetic in a local west London context: paired with the obligatory bathing costumes and high heels, Albert’s contestants often sported large Afro hairstyles, inventing and reinventing themselves on stage while articulating a particular and multifaceted black femininity as part of a widely contested and ambiguous cultural performance.

Text from the Autograph website

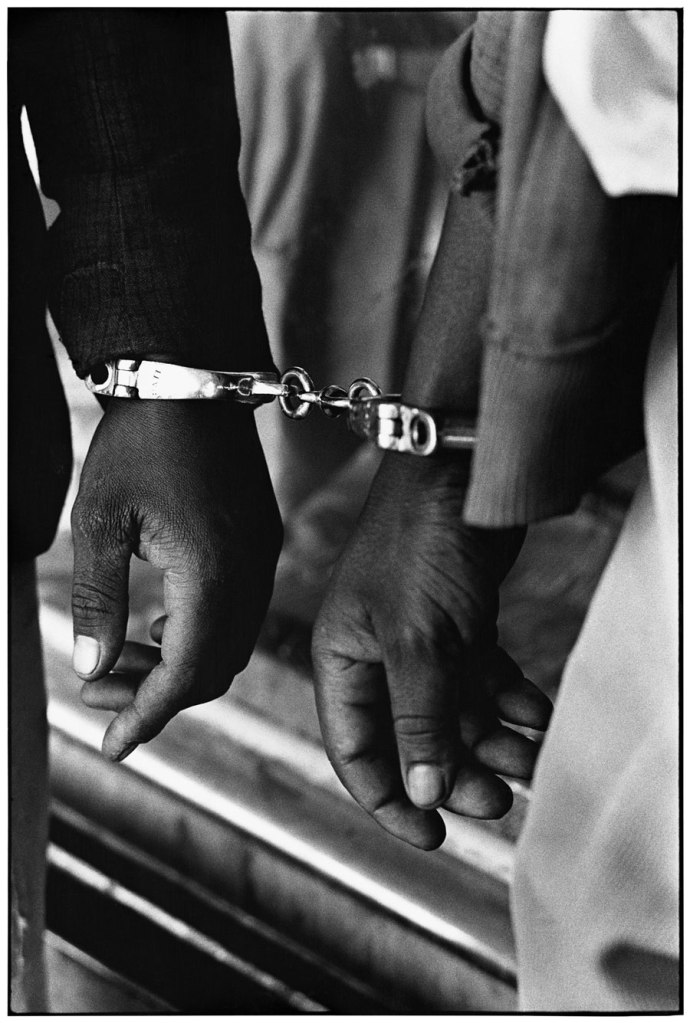

Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990)

Handcuffed blacks were arrested for being in white area illegally

1960-1966

Gelatin silver print

Image/sheet: 24.5 x 16.5 cm (9 5/8 x 6 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund, 2022.102.2

© Ernest Cole / Magnum Photos

~ Exhibition: ‘Ernest Cole: House of Bondage’ at Foam, Amsterdam, January – June 2023

~ Text/Exhibition: “Ernest Cole: Journeys through Photojournalism, Social Documentary Photography and Art,” on the exhibition ‘Ernest Cole Photographer’ at The Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, April – July 2013

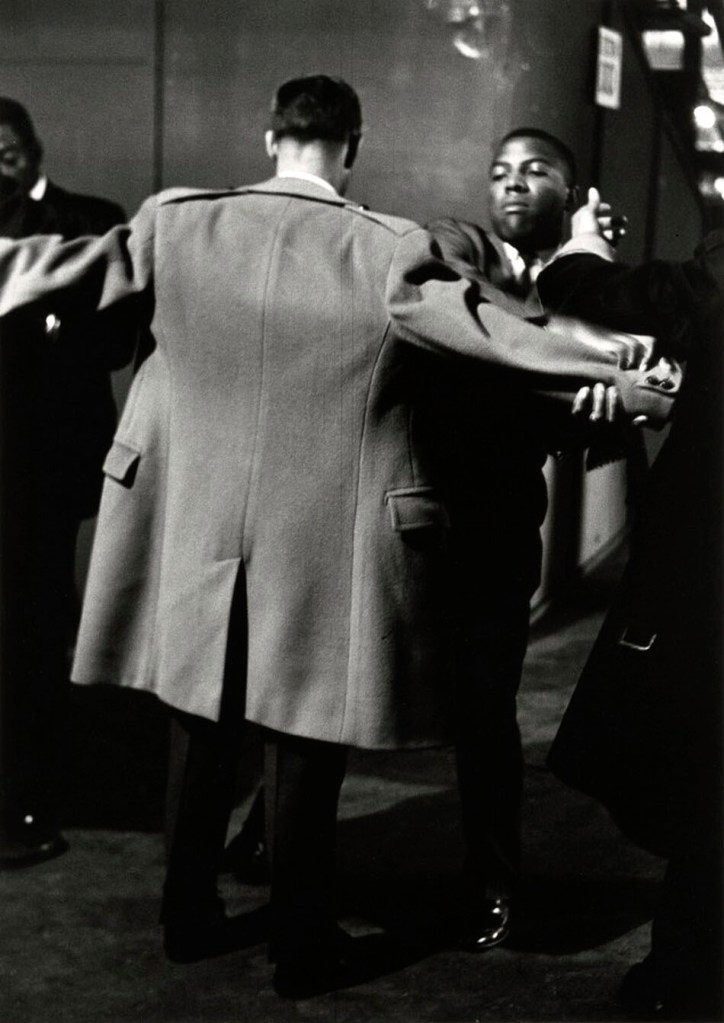

Gordon Parks (American, 1912-2006)

Newsman Being Frisked at Muslim Rally in Chicago

1963, printed 1997

Gelatin silver print

47.3 x 33.7cm (18 5/8 x 13 1/4 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Corcoran Collection (The Gordon Parks Collection)

~ Text/Exhibition: “Visible Man / Invisible photographer” on the exhibition Gordon Parks: Stokely Carmichael and Black Power at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, October 2022 – January 2023

~ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks and “The Atmosphere of Crime”‘ at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, February 2021 ongoing

~ Photographs: Gordon Parks “The Atmosphere of Crime”, 1957 February 2020

~ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: The Flávio Story’ at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center, Los Angeles, July – November 2019

~ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: Back to Fort Scott’ at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, January – September 2015

~ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: Segregation Story’ at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, November 2014 – June 2015

~ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: The Making of an Argument’ at The New Orleans Museum of Art, September 2013 – January 2014

~ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: 100 Moments’ at New York State Museum, January – May 2013

~ Exhibition: ‘Gordon Parks: Centennial’ at Jenkins Johnson Gallery, San Francisco, February – April 2013

~ Exhibition: ‘Bare Witness: Photographs by Gordon Parks’ at the Phoenix Art Museum, August – November 2011

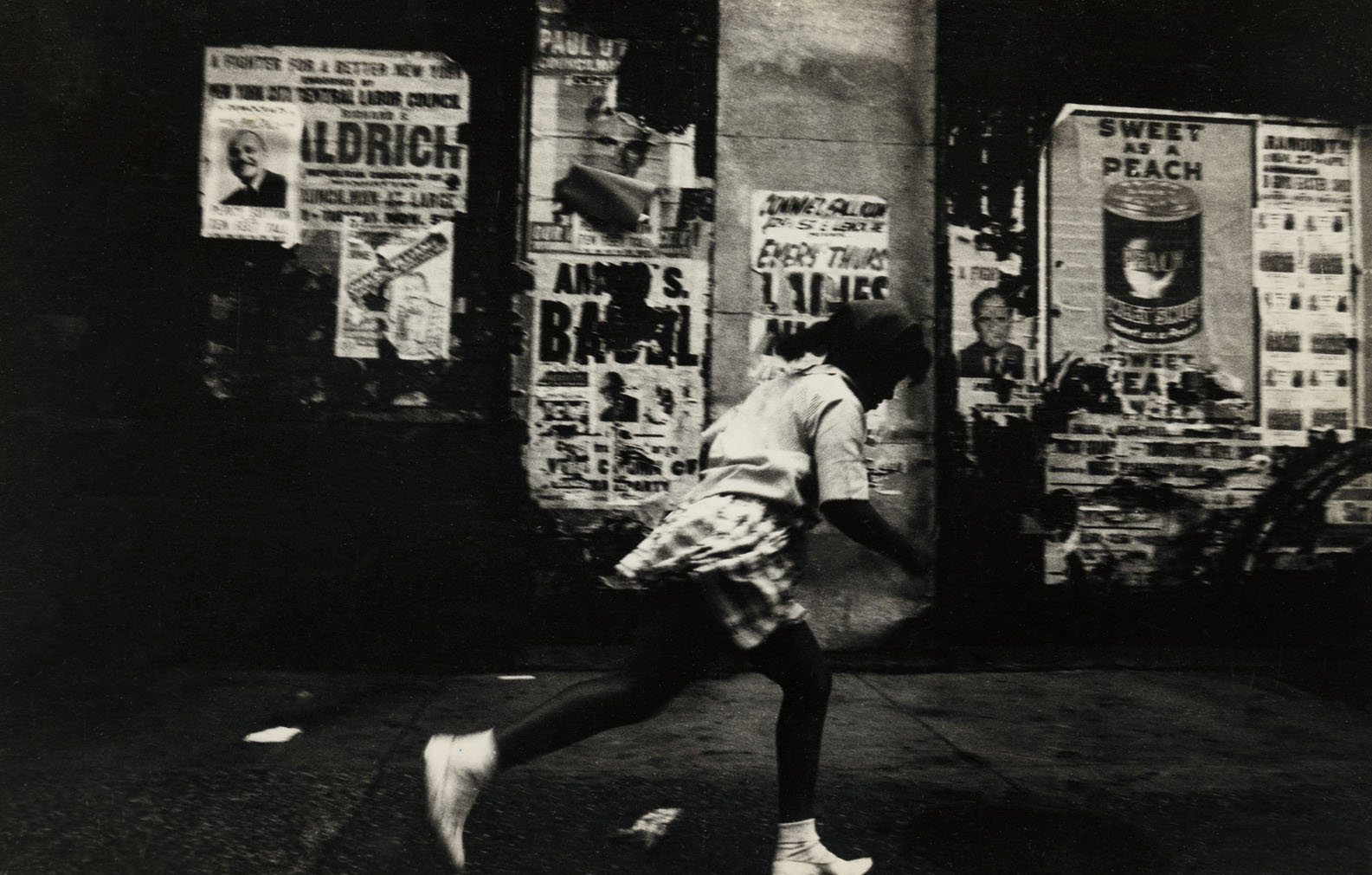

Herman Howard (American, 1942-1980)

Sweet as a Peach, Harlem, New York City

1963

Gelatin silver print

16 x 23.1cm (6 5/16 x 9 1/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

John W. Mosley (American, 1907-1969)

View of the crowd as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. addresses civil rights demonstrators at 40th Street and Lancaster Avenue, Philadelphia

August 3, 1965

Gelatin silver print

24.8 x 19.7cm (9 3/4 x 7 3/4 in.)

John W. Mosley Photograph Collection, Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection, Temple University Libraries

John W. Mosley (American, 1907-1969)

John W. Mosley (May 19, 1907 – October 1, 1969) was a self-taught photojournalist who extensively documented the everyday activities of the African-American community in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for more than 30 years, a period including both World War II and the civil rights movement. His work was published widely in newspapers and magazines including The Philadelphia Tribune, The Pittsburgh Courier and Jet magazine.

Mosley has been called a “cultural warrior” for preserving a record of African-American life in Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, one which combats “negative stereotypes and false interpretations of African-American history and culture”. …

Mosley flourished in his career as a photographer from the 1930s to the 1960s. He was known to photograph as many as four events a day, seven days a week. He traveled around Philadelphia on public transit, carrying his cameras and other equipment.

Mosley shot in black and white film. He used a large-format Graflex Speed Graphic camera. and a medium-format Rollieflex.

Proud of his heritage, Mosley chose to portray the black community positively at family, social, and cultural events that were part of daily life. He photographed individuals and families at weddings, picnics, churches, segregated beaches, sporting events, concerts, galas, and civil rights protests. During a time of racism and segregation, he emphasised the achievements of black celebrities, athletes, and political leaders.

Text from the Wikipedia website

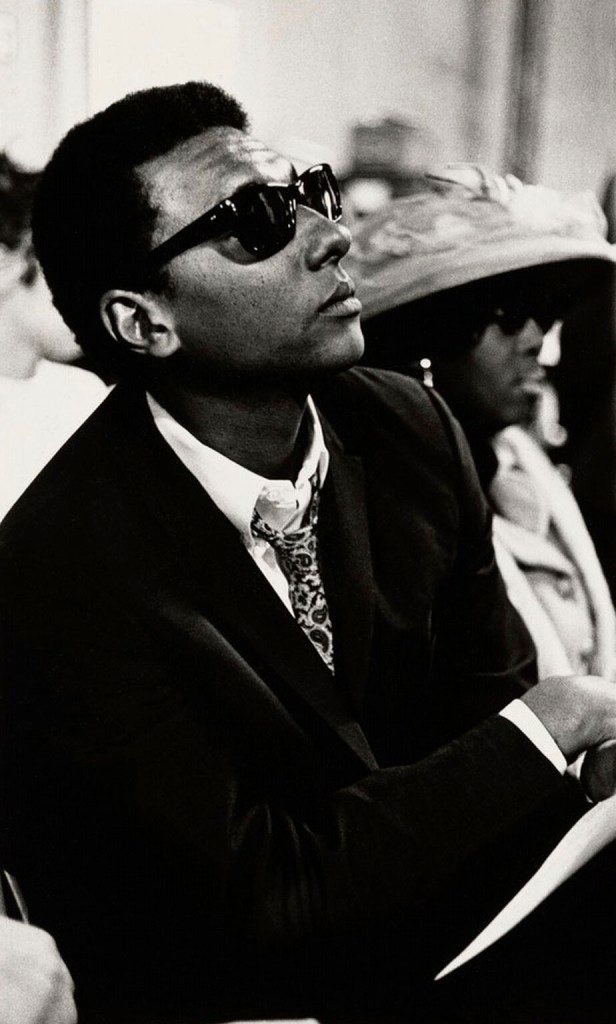

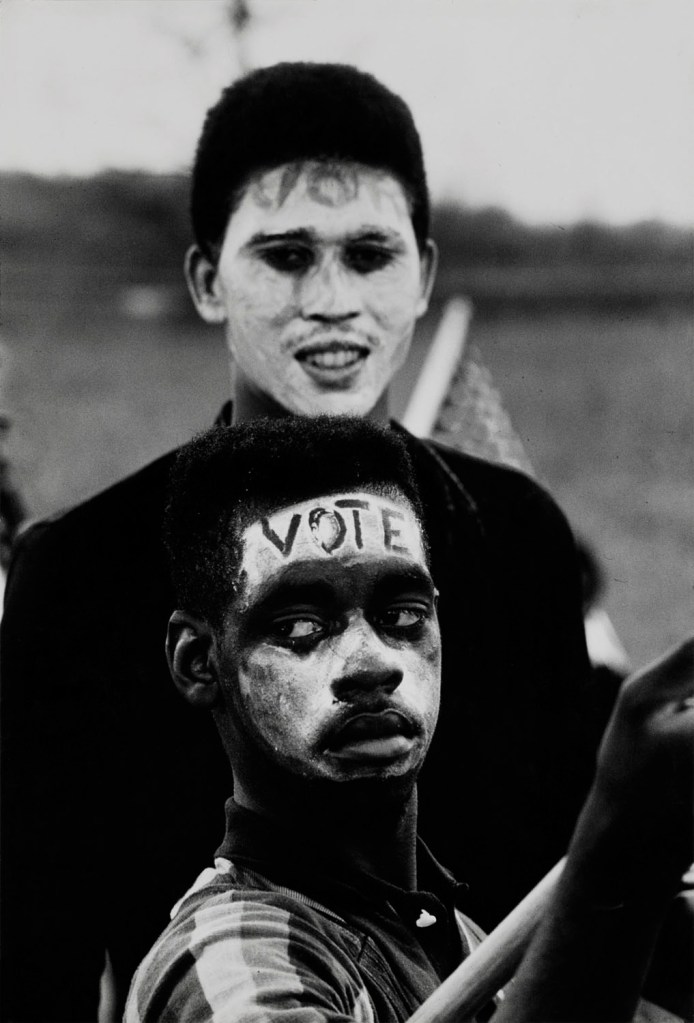

Moneta Sleet Jr. (American, 1926-1996)

Two Teenaged Supporters of the Selma March

1965, printed c. 1970

Gelatin silver print

43.3 x 29.5cm (17 1/16 x 11 5/8 in.)

Saint Louis Art Museum, Gift of the Johnson Publishing Company

© Johnson Publishing Company Archive. Courtesy J. Paul Getty Trust and Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. Made possible by the Ford Foundation, J. Paul Getty Trust, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and Smithsonian Institution

“During the Civil Rights Movement, I was a participant just like everybody else. I just happened to be there with my camera, and I felt and firmly believed that my mission was to photograph and show the side of it that was the right side.”

~ Moneta Sleet Jr.

During Sleet’s 41 years at Ebony, he worked by Martin Luther King Jr.’s side for 13 years, capturing historical moments of the civil rights movement.

Sleet began working for Ebony magazine in 1955. Over the next 41 years, he captured photos of young Muhammad Ali, Dizzy Gillespie, Stevie Wonder, Emperor Haile Selassie I, Jomo Kenyatta, former ambassador Andrew Young in a blue leather jacket and jeans in his office at the United Nations, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Liberia’s William Tubman and Billie Holiday. He gained the affection and esteem of many civil rights leaders, many of whom called on him by name. When Coretta Scott King found out that no African American photographers had been assigned to cover her husband’s funeral service, she demanded that Sleet be a part of the press pool. If he was not, she threatened to bar all photographers from the service. Besides his photo of Coretta Scott King, he also captured grieving widow Betty Shabazz at the funeral of her husband Malcolm X.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Kwame Brathwaite (American, 1938-2023)

Untitled (Charles Peaker Street Speaker, head of ANPM, after Carlos Cooks passed away, on 125th Street)

c. 1968, printed 2016

Inkjet print

37.2 x 37.2 cm (14 5/8 x 14 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund and Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund

Kwame Brathwaite (American, 1938-2023)

Black Is Beautiful.

From Marcus Garvey to the Black Panther Party, these three words powered the political dreams and material possibilities of generations of Black people living in the United States. Over the course of seven decades, the recently departed photographer Kwame Brathwaite constructed a glorious visual lexicon to articulate a Pan-Africanist argument. Whether through his rhythmic documentation of the jazz scene in Harlem and the Bronx, or his cofounding of the African Jazz-Art Society & Studios (AJASS), Brathwaite positioned photography at the nexus of Black artistic, political, and musical expression. Moving between concert halls and boxing rings, portrait studios and protest movement scenes – his Hasselblad in hand – Brathwaite chronicled self-determination and creativity that celebrated Blackness in all of its forms. Each of his photographs brims with bombastic flare and undeniable elegance. Their narrative potential is still transfixing.

“Black Is Beautiful was my directive,” Brathwaite said. “It was a time when people were protesting injustices related to race, class, and human rights around the globe. I focused on perfecting my craft so that I could use my gift to inspire thought, relay ideas, and tell stories of our struggle, our work, our liberation…. Oppression still exists today, and we must keep fighting, keep on pushing until we are free. A luta continua, a vitória é certa – the struggle continues, victory is certain.”

Oluremi C. Onabanjo, Esther Adler, Roxana Marcoci, Marilyn Nance, David Hartt, Michael Famighetti. “Remembering Kwame Brathwaite (1938-2023),” on the MoMA website, Dec 26, 2023 [Online] Cited 30/11/2025

Doris A. Derby (American, 1939-2022)

Black-owned Grocery Store, Sunday, Mileston, Mississippi

1968

Gelatin silver print

21.9 x 32.7cm (8 5/8 x 12 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of David Knaus

© Doris A. Derby

While the Black Arts Movement is generally pegged to the 1960s and ’70s, the point of departure for Willis and Brookman was the work of photographer Roy DeCarava, who in 1955, on the cusp of the civil rights movement, released a book titled The Sweet Flypaper of Life. The book featured portraits of Black life in Harlem activated by a fictitious character named Mary Bradley, a narrative invention of Harlem Renaissance writer Langston Hughes.

In the book, Sister Mary’s musings unfold within DeCarava’s photographic landscape. The exhibition includes an image from the book featuring bassist Edna Smith, whose face is partially illuminated by a single light in the distance. Her downward gaze conveys a sense of somberness that’s echoed by the shadows that surround her, while the single glint of light coming off her wristwatch draws attention to the bass like the beacon from a lighthouse.

Published decades following the Harlem Renaissance, one year after Brown v. Board of Education and months after the murder of Emmitt Till, DeCarava’s book came at a critical moment in art history, a time when photography became more broadly recognised as fine art through groundbreaking exhibitions like “The Family of Man” at the Museum of Modern Art, also in 1955. With that recognition, Black artists seized an opportunity to compose compelling visual narratives. “The collaboration between Langston Hughes and Roy De Carava was influential for so many photographers and artists, in part because De Carava and Hughes were looking at their respective communities, and they put together a story that was looking inward,” says Brookman.

Colony Little. “A Show at the National Gallery Highlights the Role of Photography in the Black Arts Movement,” on the ARTnews website November 20, 2025 [Online] Cited 24/11/2025

Ray Francis (American, 1937-2006)

Genie

1971

Gelatin silver print

13.97 × 17.78cm (5 1/2 × 7 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Ray Francis (American, 1937-2006)

Ray Francis was a founding member of the Kamoinge Workshop. He received his first camera in 1952, at the age of 15. In 1961 he met Louis Draper, with whom he formed Group 35. In 1963 Group 35 merged with other photographers to create Kamoinge, where Francis contributed significantly by creating a darkroom for the group and working as a photo editor for the Black Photographers Annual.

His photographic work spanned still life, portraiture, and landscape, often using dramatic light and shadow, influenced by Johannes Vermeer’s use of composition. Francis also made contributions as an educator, teaching at the Bedford-Stuyvesant Neighborhood Youth Corps (1966–1969) and later serving as director of the New York City Board of Education’s photography program for Intermediate School 201 from 1970 to 1974.

Text from the National Gallery of Art website

Kwame Brathwaite (American, 1938-2023)

Untitled (Portrait, Reels as Necklace)

c. 1972, printed later

Inkjet print

74.93 × 74.93cm (29 1/2 × 29 1/2 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Gift of Funds from Renée Harbers Liddell and Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Kwame Brathwaite

Kwame Brathwaite, [was] a photographer, musician and African American activist who was a unique politico-aesthete. With his brother Elombe Brath, he virtually invented the phrase “Black Is Beautiful” in the 1960s by photographing the Grandassa Models in Harlem: young African American women who became the sensational template for beauty, doing away with the usual cosmetic products and the usual white standard of femininity.

Black Is Beautiful became a radical rallying cry, an inspired three-word prose poem and manifesto for change. Simply to assert that black people were beautiful was a liberating force in art, politics and culture, and Brathwaite became a part of Black power’s pan-Africanist movement by photographing Muhammad Ali before his Rumble in the Jungle fight in Zaire in 1974. He was the exclusive photographer for the Jackson 5’s African tour, and became the house photographer for the Apollo theatre, building an amazing archive of black musicians, and with Elombe was the driving force behind bringing Nelson Mandela to speak in Harlem.

Peter Bradshaw. “Black Is Beautiful: The Kwame Brathwaite Story – exhilarating record of game-changing photographer,” on The Guardian website Fri 10 Oct 2025 [Online] Cited 30/11/2025

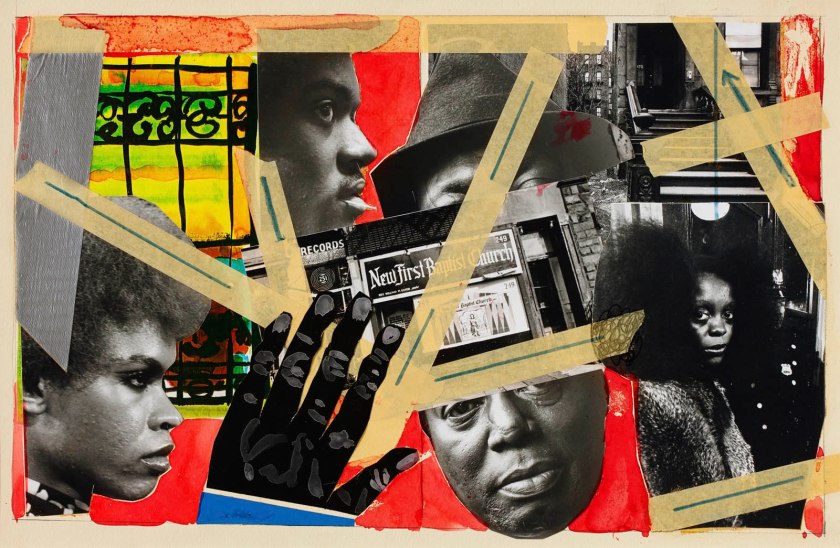

Romare Bearden (American, 1911-1988)

110th Street Harlem Blues

1972

Collage

© Romare Bearden Foundation

African-American artist, activist, and writer Romare Bearden was close friends with film producer and photographer Sam Shaw, and he often drew inspiration from Shaw’s creative projects. The portraits incorporated into this collage feature outtakes of extras from a movie Shaw may have documented as set photographer.

Bearden’s work reflects his improvisational approach to his practice. He considered his process akin to that of jazz and blues composers. Starting with an open mind, he would let an idea evolve spontaneously. “You have to begin somewhere,” he once said, “so you put something down. Then you put something else with it, and then you see how that works, and maybe you try something else and so on, and the picture grows in that way.”

Text from the Fraenkel Gallery Facebook page via DC Gallery, New York

Other works of art in the show are a testament to the medium’s lasting influence on established visual artists. Among these was Romare Bearden, who in the mid-1960s began exploring photographic collage; it would become an art form he used to create his most influential works. “Romare Bearden has always been integral to understanding the Black Arts Movement,” says Brookman. “By using photographs in his collages, he makes a direct connection between photography in all of its forms and the Black Arts Movement. That was something I had not seen or thought a lot about before, how much photography is incorporated into his visual art, including painting, during that time.”

Colony Little. “A Show at the National Gallery Highlights the Role of Photography in the Black Arts Movement,” on the ARTnews website November 20, 2025 [Online] Cited 24/11/2025

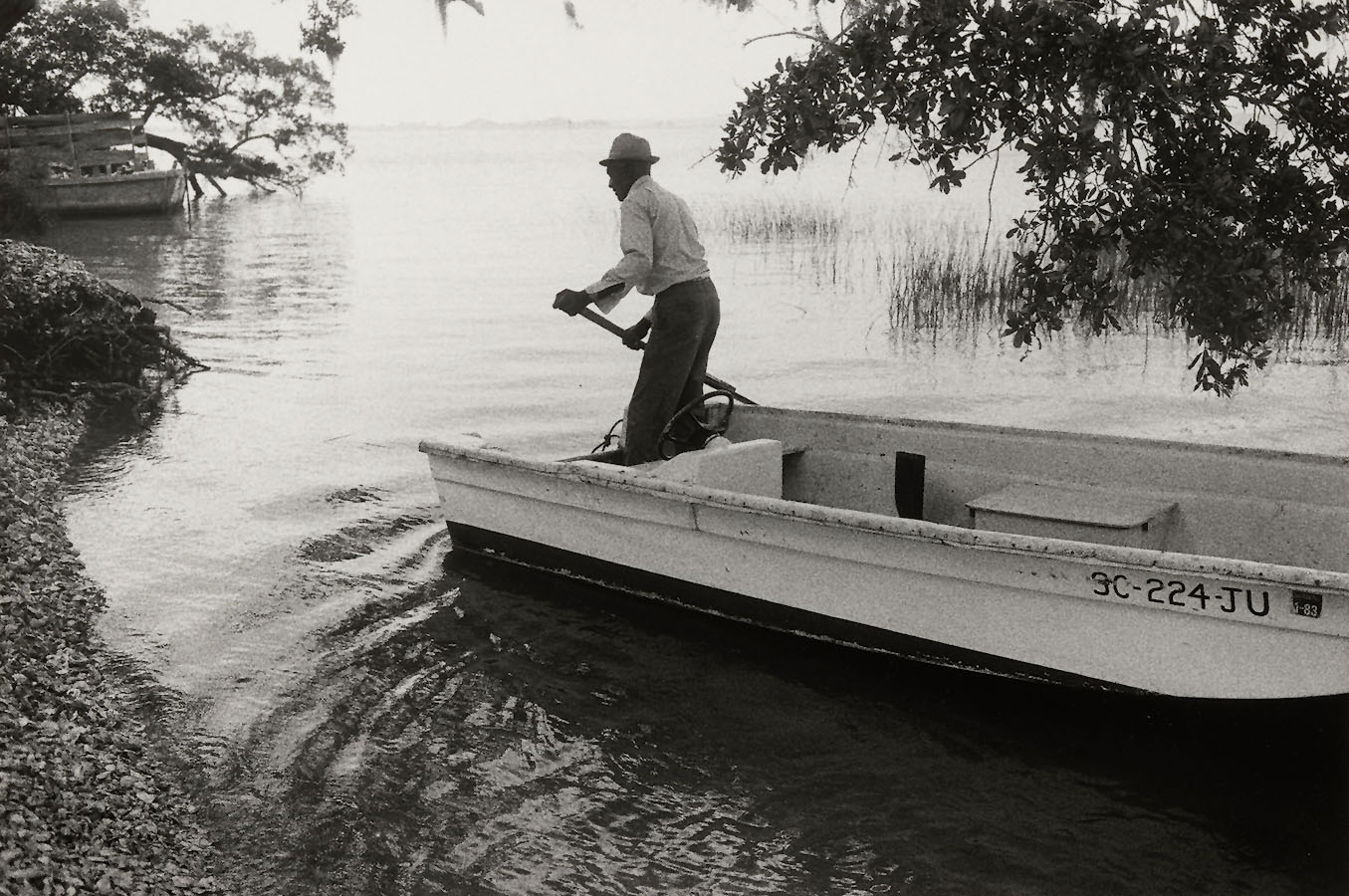

Chester Higgins (American, b. 1946)

Father prays over son on Osu Beach, Accra, Ghana

1973

Gelatin silver print

22.8 x 34cm (9 x 13 3/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Chester Higgins. All Rights Reserved. Courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery

Dawoud Bey (American, b. 1953)

The Blues Singer, Harlem, NY

1976

Gelatin silver print

22.1 x 32.7 cm (8 11/16 x 12 7/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Gift of the Charina Endowment Fund in memory of Robert B. Menschel

~ Text/Exhibition: “Street cred,” on the exhibition Dawoud Bey: Street Portraits at Denver Art Museum, November 2024 – May 2025

~ Exhibition: ‘Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems: In Dialogue’ at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, April – July 2023

~ Exhibition: ‘Dawoud Bey: An American Project’ at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April – October 2021

~ Exhibition: ‘Dawoud Bey: An American Project’ at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, November 2020 – March 2021

Barbara DuMetz (American, b. 1947)

Kraft Foods advertisement

1977

Barbara DuMetz (American, b. 1947)

Barbara DuMetz (born 1947) is an American photographer and pioneer in the field of commercial photography. She began working in Los Angeles as a commercial photographer in the 1970s, when very few women had established and maintained successful careers in the field, especially African-American women. Over the course of her career, “she made a major contribution to diversifying the landscape of images that defined pop culture in the United States.”

DuMetz is known for her work with African-American celebrities, corporations and images of everyday life in African-American communities. …

DuMetz has been a professional photographer for more than four decades. Over the course of her career, she has produced award-winning images for advertising agencies including Burrell Advertising, J. P. Martin Associates and InterNorth Corporation. Her photographs have appeared in African-American publications including Black Enterprise, Ebony, Essence, Jet and The Crisis. She has taken commercial photographs for corporations including The Coca-Cola Company, Delta Air Lines and McDonald’s Corporation.

DuMetz ran and maintained three different photography studios located in the Los Angeles area where she was contracted by department stores, record companies, graphic design studios, advertising agencies, public relations firms, film production companies, actors and business professionals. DuMetz’s has shot photo layouts of celebrities and artists and personalities including Maya Angelou, Ernie Barnes, Bernie Casey, Pam Grier, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Quincy Jones, Samella Lewis, Ed McMahan, Thelonious Monk, Lou Rawls, Della Reese, Richard Roundtree, Betye Saar, Charles Wilbert White, and Nancy Wilson. Her show The Creators: Photographic Images of Literary, Music and Visual Artists, at the Southwest Arts Center in Atlanta, Georgia, in 2015, included images of over two dozen African-American artists whom she has photographed.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Ming Smith (American, b. 1947)

Sun Ra Space II, New York, New York

1978

Gelatin silver print

15.24 × 22.4cm (6 × 8 13/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Charina Endowment Fund

“You don’t make art for money, especially as a Black artist. You do it because there is that need to create – and that has been part of my survival; that has helped me survive.”

“My work as a photographer was to record, culturally, the period of time in which I lived – and I recorded it as an artist.”

“Oh no, it’s all discovery, it’s all improvisation. It’s like when jazz musicians solo. They improvise, and photography is definitely that, for me.”

“Whether I’m photographing a person on the street, someone I know, or on an assignment, I’m doing it because I admire them. I like the sense of exchange – they’re giving and I’m taking, but I’m also giving them something back. There were certain people who would understand what I was looking for and would try to give me a photograph by posing. Whatever I’m shooting, whether it’s a portrait or a place, my intention is to capture the feeling I have about that exchange and that energy.”

Ming Smith

Coreen Simpson (American, b. 1942)

Self-Portrait

1978

Gelatin silver print

21.6 x 16.8cm (8 1/2 x 6 5/8 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

© Coreen Simpson

Simpson’s career launched when she became editor for Unique New York magazine in 1980, and she began photographing to illustrate her articles. She then became a freelance fashion photographer for the Village Voice and the Amsterdam News in the early 1980s, and covered many African-American cultural and political events in the mid-1980s. She is also noted for her studies of Harlem nightlife. She constructed a portable studio and brought it to clubs in downtown Manhattan, barbershops in Harlem, and braiding salons in Queens. Her work’s ability to present a wide variety of subjects with “depth of character and dignity” has been compared to that of Diane Arbus and Weegee.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Simpson became a photographer after noticing that she could make better images than the ones used to illustrate her stories as a freelance lifestyle writer. She took the chance to start creating the images she wanted to see. In 1976, she contacted her friend Walter Johnson, a street photographer who worked at a photo lab in Manhattan, with whom she had been acquainted from her modeling days, and asked if he could teach her how to use a camera. He showed her how to use it, and as soon as she got a hold of it, she became unstoppable.

She argues that great images are the key to having a successful published story. “You have to feel good about yourself, and good about the article that you’re presenting to the public,” she says. “So what makes it good? It’s the visuals. The visuals make it good.”

Briana Ellis-Gibbs. “Photographer Coreen Simpson’s illustrious career capturing Toni Morrison and Muhammad Ali: ‘I’ve never gotten bored’,” on The Guardian website Tue 21 Oct 2025 [Online] Cited 30/11/2025

Anthony Barboza (American, b. 1944)

Grace Jones, New York City

1970s

Gelatin silver print

27 × 23.7cm (10 5/8 × 9 5/16 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Alfred H. Moses and Fern M. Schad Fund

Anthony Barboza (American, b. 1944)

Anthony Barboza (born 1944 in New Bedford, Massachusetts) is a photographer, historian, artist and writer. With roots originating from Cape Verde, and work that began in commercial art more than forty years ago, Barboza’s artistic talents and successful career helped him to cross over and pursue his passions in the fine arts where he continues to contribute to the American art scene.

Barboza has a prolific and wide range of both traditional and innovative works inspired by African-American thought, which have been exhibited in public and private galleries, and prestigious museums and educational institutions worldwide. He is well known for his photographic work of jazz musicians from the 1970s – ’80s. Many of these works are in his book Black Borders, published in 1980 with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. In an article printed in 1984 in The City Sun, he said, “When I do a portrait, I’m doing a photograph of how that person feels to me; how I feel about the person, not how they look. I find that in order for the portraits to work, they have to make a mental connection as well as an emotional one. When they do that, I know I have it.” Many of his photographs achieve his signature effect through the careful use of lighting and shadows, manipulation of the backdrop, measured adjustments to shutter speeds, composition, and many other techniques and mediums at his command.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Nellie Mae Rowe (American, 1900-1982)

God Loves Us All

1978

Marker on silver gelatin print

15.9 x 29.2cm (6 1/4 x 11 1/2 in.)