Exhibition dates: 24th July – 12th August, 2018

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

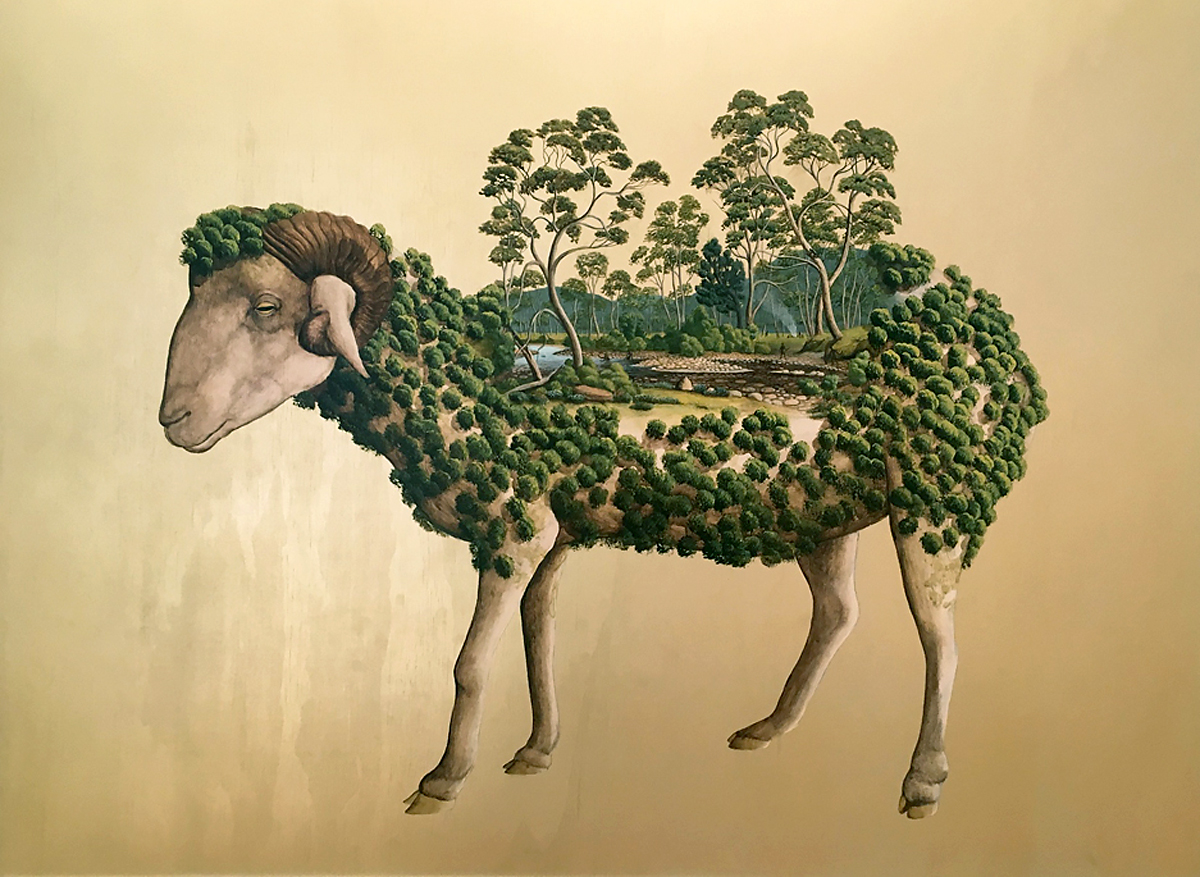

Usurper Ruminant

2016

Acrylic on gold enamel on board

120cm x 90cm

Clarion call

The sky is blue, the sun is shining and yet, in this era of the Anthropocene, the Earth is in deep shit. Through the activities of a virus, a contagion that infests the planet… that is – the ego, the selfishness of the individual human and, collectively, of the human race – “we are perhaps amongst the first to contemplate not just our own finite existence, but the doomed fate of the Earth itself.”

My friend Dale Cox’s exhibition Inner Logic at Australian Galleries dissects this situation in a most intelligent and imaginative manner. Instead of didactic protest, Cox uses the language of Australian pastoral landscape, iconic edifice and stratigraphic cross section to make ironic comment on popular culture, history and religion. As you dissect the various influences and concepts within the work you chuckle to yourself at the artist’s inventiveness and humour.

Mixing the tight style and formal, classical beauty of Australian colonial painting (with reference in particular to the work of John Glover) with the uncanny sense of reality and precision found in the paintings of Jeffrey Smart, Cox twists his realities and points of view. Shopping trolleys have a strange perspective when filled with Australian colonial landscapes; aircraft stairs seem strangely twisted as they lead to a geological cross-section topped with verdant greenery (a journey through time); clouds in the burning landscape look like that of an atomic bomb; an Uluru-like profile of Elvis in the Australian bush is dotted with tents and encampments; and Australian ute’s of unlikely shape sit at the base of a constructed Elvis edifice, the most prominent thing to my mind in the painting being the four air conditioning units at the base of the construction cabin, sitting in an absolutely barren landscape. The perspicacity of Cox’s (re)marks is exemplary.

My favourite works in the exhibition are the Usurper paintings. Here Cox condenses the customs, traditions and rituals of the human race (colonisation, farming, habitation – power, possession, destruction and modification of the environment and its animals) onto the body of the (b)ovine family, the livestock “genetically modified over time through the artificial selection of desirable traits by humans, with a view to increasing the docility of the animals, their size and productivity, their quality as agricultural products, and other culturally desired features,”1 to serve humans who are substantially dependent on their livestock for sustenance and other purposes. These artificial bodies, these illegitimate usurpers, float on a sea of gold enamel and wood grain form.

Cox’s declamations, his inner logic if you like, document in the most inventive way the liturgy of errors of the human race. His work is a clarion call for humans to be better custodians (for that is what we are) of the Earth. Through his subversive paintings, the artist “challenges the myopic tendency for us humans to fixate on ourselves in a way that bodes poorly for our ability to see the bigger picture and act as stewards for the entire planet rather than as self serving, selfish species.” (Email to the author, 28 July 2018). His humors (basic substances which are in balance when a person, or in this case the Earth, is healthy) add to the raised voices against the naysayers of global warming, the backward looking fossil fuel industry, the power of nations and corporations, and the vested interests of the rich and powerful, mainly men. It’s time for the dreamers, the artists, and the spiritual to confront these dinosaurs of the past, so that they may shape the future. So that the human race can cast aside their shadow and learn to walk on the Earth without leaving tracks.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to Dale Cox for allowing me to publish the text and the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Shaman

“There are two kinds of people in this world.

There are those who are dreamers and those who are being dreamed.

There comes a time in every mans life when he must encounter his past.

For those that are dreamed, who have no more than a passing acquaintance with power, this moment is usually played out on their death beds as they try to bargain with fate for a few more moments of life time.

But for the dreamer, the person of power, this moment takes place alone, before a fire, when he calls upon the spectres of his personal past to stand before him like witnesses before the court…

I am not speaking of remembering the past. Anyone can remember the past, and in remembering we frame it to serve and justify the present. Remembering is a conscious act and therefore subject to embellishment. Remembering is easy.

The person of power sits alone before the fire and confronts his past. He hears the testimony of these spectres and he dismisses them one by one. He acquits himself of his past. If you comprehend this, the man of power has no past. No history that can claim him. He has cast aside his shadow and learnt to walk in the snow without leaving tracks.”

Dr Alberto Villoldo

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Usurper Transplant

2016

Acrylic on gold enamel on board

120cm x 90cm

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Usurper Glover

2016

Acrylic on gold enamel on board

120cm x 90cm

John Glover (England 1767 – Australia 1849, Australia from 1831)

The River Nile, Van Diemen’s Land, from Mr Glover’s farm

1837

Oil on canvas

76.4 x 114.6cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Felton Bequest, 1956

John Glover’s colonial landscapes can be divided into two groups: pastoral scenes of the land surrounding his own property, and pre-contact Aboriginal Arcadias. Although the Aboriginal figures are at times generic, they are shown as active participants in the landscape. Such scenes were, however, entirely imagined, as Glover encountered very few Tasmanian Aboriginal people while in the colony. Glover had not experienced the conflict or witnessed the violence between Tasmanian Aboriginal resistance fighters and white settlers during the 1820s. By the time of his arrival in 1831, the Tasmanian Aboriginal survivors had been forced to leave Country and relocate to Flinders Island.

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Tract 38 (Burning landscape)

2012

Acrylic on canvas

102 x 152cm

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Tract 38 (Burning landscape) (detail)

2012

Acrylic on canvas

102 x 152cm

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Flight SQ2118 to Thailand

2018

Acrylic on board

81 x 122cm

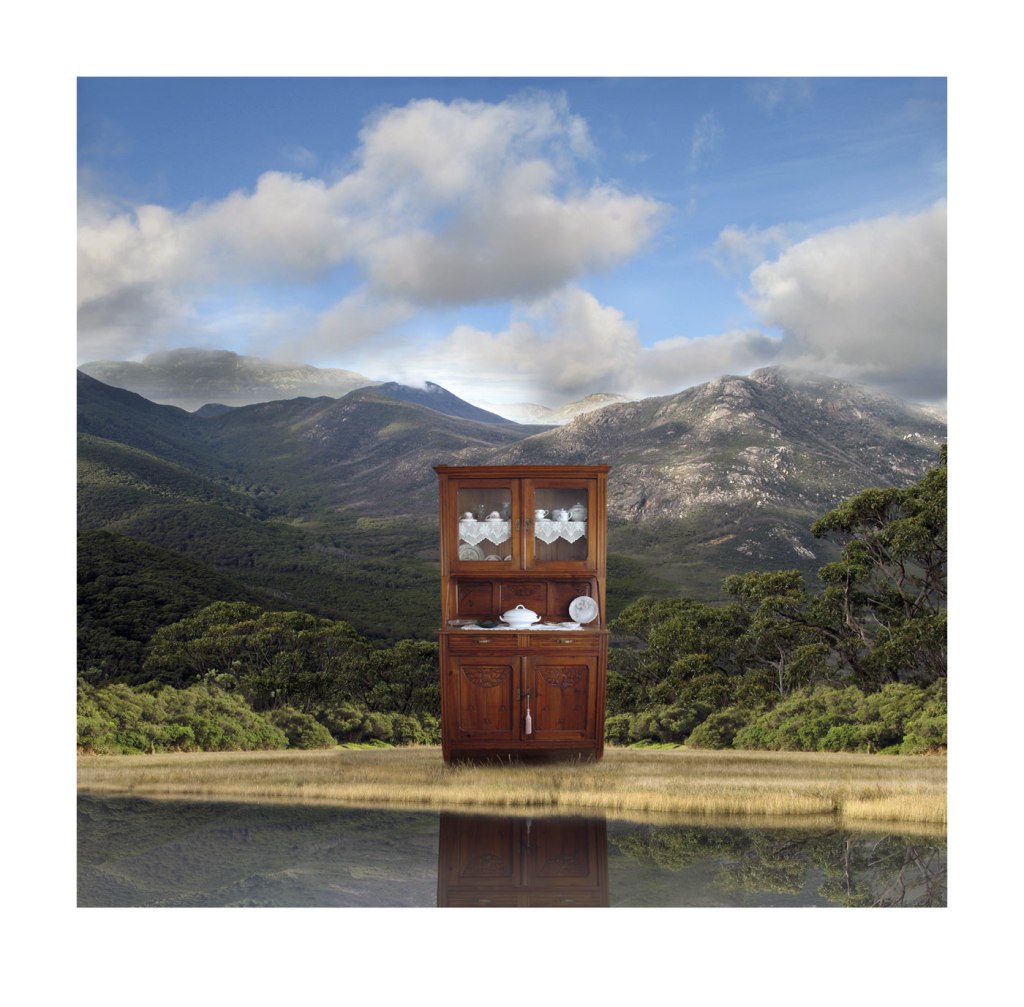

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Rewilding II

2018

Acrylic on board

81 x 122cm

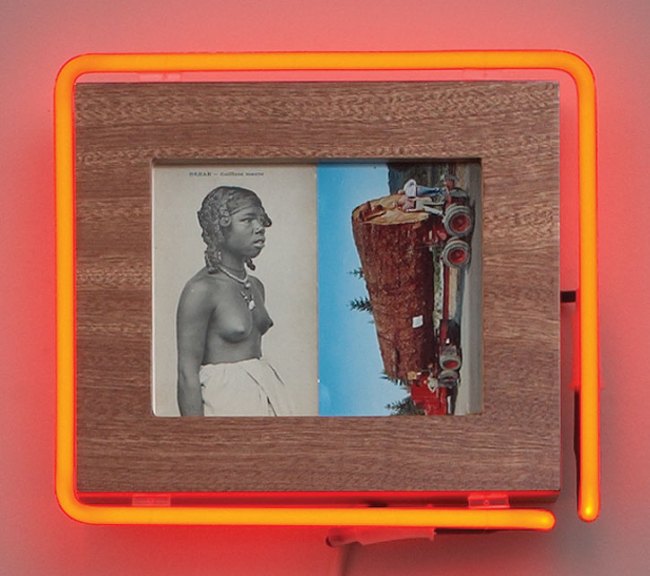

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Anticolonial

2018

Acrylic on board

81 x 122cm

Inner Logic 2018

The motifs and elements in this exhibition are all related to our human predicament; to this era of the Anthropocene and our unique capacity amongst living things to contemplate our own mortality. While we have grappled with our impermanence for thousands of years, we are perhaps amongst the first to contemplate not just our own finite existence, but the doomed fate of the Earth itself. A kind of double death.

It’s a lot to take on board.

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, we are well practiced at diversion, denial and a kind of wishful thinking when it comes to our fate. Religion has served us rather well as a kind of ‘soft landing’ into the unknown; furnishing us cradle to grave with a reassuring framework towards a life after death.

It is an intoxicating idea that when we die we go elsewhere. Anything but death seems like a plan. Indeed, many opine that a belief in an afterlife is essential to the very fabric of humanity, that our lives would be meaningless if it simply ended. Perhaps there is an inner logic to this: Is there a point to a life that simply ends?

Our aversion to annihilation runs deep, and in light of some fairly compelling arguments that it is so, humanity is slow to accept the deal. And now that we are facing mounting evidence that we are hurtling towards an environmental collapse of our own making, it seems the all too human ability to simply avert our gaze is once again at play. Desperate times call for desperate measures in collective denial, and so it seems we enter the post-truth era.

There are myriad ways in which we pull off this practised art of self-delusion. Central to it is our unerring fascination with ourselves, our own species. ‘Anthropocentricity’ has served us for millennia as an essential tool of survival by strengthening our ties as family units, tribes, villages and, by extension, nations. The gods we created invariably took a patriarchal form, and we still cling to these heroic manifestations of our own image.

Even our innate altruism appears limited to all things ‘us’. We seem ill-equipped as stewards of the planet of being capable of seeing the bigger picture, of accommodating the survival of all species. All animals are necessarily hardwired to fixate on their own collective survival at the expense of other species, but it is humans alone who can progress that exclusivity to global obliteration.

I generalise, of course. Many manage to stare reality squarely in the face, and many more understand the importance of the broader environment. And it will get harder to remain wilfully ignorant, as the ecological collapse is well underway, overtaking even the gloomiest of predictive models. It is in plain sight and will only become harder to ignore.

The environmental problems we face appear too colossal for individuals to consider; it all seems too overwhelming, too daunting. These are not ‘human-sized’ problems after all. But if we can apply the same collective fervour and inventiveness we applied to bettering our human lot, if we can find a global will to turn our remarkable capacity for enterprise in science, technology and innovation to repairing the planet as a whole, we may have just cause for hope.

Dale Cox

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

The Bungle Bungles

2018

Acrylic on board

122 x 244cm

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Always on my mind

2018

Acrylic on board

101 x 244cm

Anthropocene definition

Relating to or denoting the current geological age, viewed as the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.

Evolutionary psychology definition

Evolutionary psychology is a theoretical approach to psychology that attempts to explain useful mental and psychological traits – such as memory, perception, or language – as adaptations, i.e., as the functional products of natural selection.

The purpose of this approach is to bring the functional way of thinking about biological mechanisms such as the immune system into the field of psychology, and to approach psychological mechanisms in a similar way.

In short, evolutionary psychology is focused on how evolution has shaped the mind and behaviour. Though applicable to any organism with a nervous system, most research in evolutionary psychology focuses on humans.

Text from the Science Daily website

Evolutionary psychologists argue that much of human behaviour is the output of psychological adaptations that evolved to solve recurrent problems in human ancestral environments…

Evolutionary psychologists hold that behaviours or traits that occur universally in all cultures are good candidates for evolutionary adaptations including the abilities to infer others’ emotions, discern kin from non-kin, identify and prefer healthier mates, and cooperate with others.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Tract definition

A short piece of writing, especially on a religious or political subject, that is intended to influence other people’s opinions; a large area of land; a major passage in the body, large bundle of nerve fibres, or other continuous elongated anatomical structure or region.

Usurper definition

A usurper is an illegitimate or controversial claimant to power, often but not always in a monarchy. In other words, a person who takes the power of a country, city, or established region for themselves without any formal or legal right to claim it as their own. Usurpers are both those who overtake a region by often unexpected physical force, as well as individuals or organisations who overtake a region through political influence and subterfuge – though the word “usurper” denotes a single person; either an individual who acted alone, or the leader of a group which supported their controversial claim.

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Untitled (Lunar lander of wood)

2012

Acrylic on board

51 x 77cm

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Cold War Reliquary

2014

Mixed media Wood acrylics gold enamel metal rock glass

Dimensions variable

Created for the Blake Prize

Cold War Reliquary 2015-2016

A reliquary (also referred to as a shrine or by the French term châsse) is a container for relics. These may be the purported physical remains of saints, such as bones, pieces of clothing, or some object associated with saints or other religious figures. (Wikipedia definition)

.

My sculpture is a vessel – a craft, a portal, a reliquary. Like many Religious objects its serves as a nexus, a transport between Earth and Heaven. The Apollo Lunar Module carried the first Human to the Moon landing on July 20 1969. I was 3 months old. Russia had landed an unmanned craft safely on the moon ten years earlier. The ‘Space Race’ was chiefly an assertion of Ideological superiority between Communism and Capitalism, and the most symbolic battlefield of the ‘Cold War’.

I have long thought of mans tentative forays into space as a kind of membrane piercing journey into the Spiritual – the body released of its Earthly mass and transcended into the Heavens. The reference to a Religious Relic and object of Art – a reliquary for the precious moon rock it houses within the glass dome, elevates a Mechanical Machine to the status of a Religious Relic and is intended to supplant and parody the Christian Canon that asserts our ascension to Heaven (or Hell) upon death.

The essential role of Science as the facilitator of Space Exploration is significant, and as such the Spacecraft itself is venerated here as a Religious object.

The use of Quasi Religious painted panels directly references early Christian Art, whilst most of the Latin Inscriptions are direct translations of NASA Radio Transcripts between (Earth) Base Command and the Astronauts during the critical stages of the Moon landing, and the first historic moments upon landing. Buzz Aldrins remark as he first set foot on the moon was “Beautiful, beautiful. Magnificent desolation.” In Latin Magnificus in desertum.

Dale Cox

Cold War Reliquary

The Cold War Reliquary is a vessel – a spacecraft, and a Holy Relic. Like many Religious objects, it serves as a nexus, a transport between Earth and Heaven.

I have long thought of man’s forays into space as a kind of membrane piercing journey into the Spiritual – the body released of its Earthly mass and transcended into the Heavens. This reliquary for the precious moon rock it houses within a glass dome, elevates a Mechanical Machine to the status of a Religious Relic and playfully parodies the Space Race as the era in which Science finally transcended Religion.

Inner Logic continues Dale Cox’s insightful and evocative explorations into environmental, spiritual and anthropological themes; investigating the impact of humankind on this planet and our collective search for meaning.

“The motifs and elements within the current exhibition of my paintings all are in some way or another related to our human predicament and this era of the anthropocene and our unique capacity amongst living things to contemplate our own mortality,” says Cox, “We humans have been grappling with our own mortality for thousands of years. Are we today, however amongst the first generations to contemplate not just our own finite existence, but also the doomed fate of the Earth itself? A kind of double death…”

Inner Logic presents a dynamic series of recent paintings in Dale Cox’s highly distinctive visual language, in which elements from the natural world and icons from popular, religious, industrial and historical culture are assembled in precarious, yet harmonious balance upon a backdrop of the vast unknown. Meticulously executed in acrylic paint, these works are visually intricate and conceptually dense, yet the clarity and significance of their message resonates with immediacy and power.

Dale Cox is equally proficient in sculpture as he is in painting and works across a wide range of media. This exhibition presents the artist’s compelling Cold War Reliquary (Finalist in the 64th Blake Prize); a magnificent recreation of the Lunar Lander spacecraft realised as a gilded religious receptacle, “My sculpture is a vessel – a spacecraft, a portal, a reliquary. Like many religious objects its serves as a nexus, a transport between Earth and Heaven. I have long thought of man’s forays into space as a kind of membrane piercing journey into the spiritual – the body released of its Earthly mass and transcended into the Heavens. This reliquary for the precious moon rock it houses within a glass dome, elevates a Mechanical Machine to the status of a Religious Relic and playfully parodies and challenges the Christian Church.” Dale Cox, 2018

Press release from Australian Galleries

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Art Mart

2018

Acrylic on board

120 x 89cm

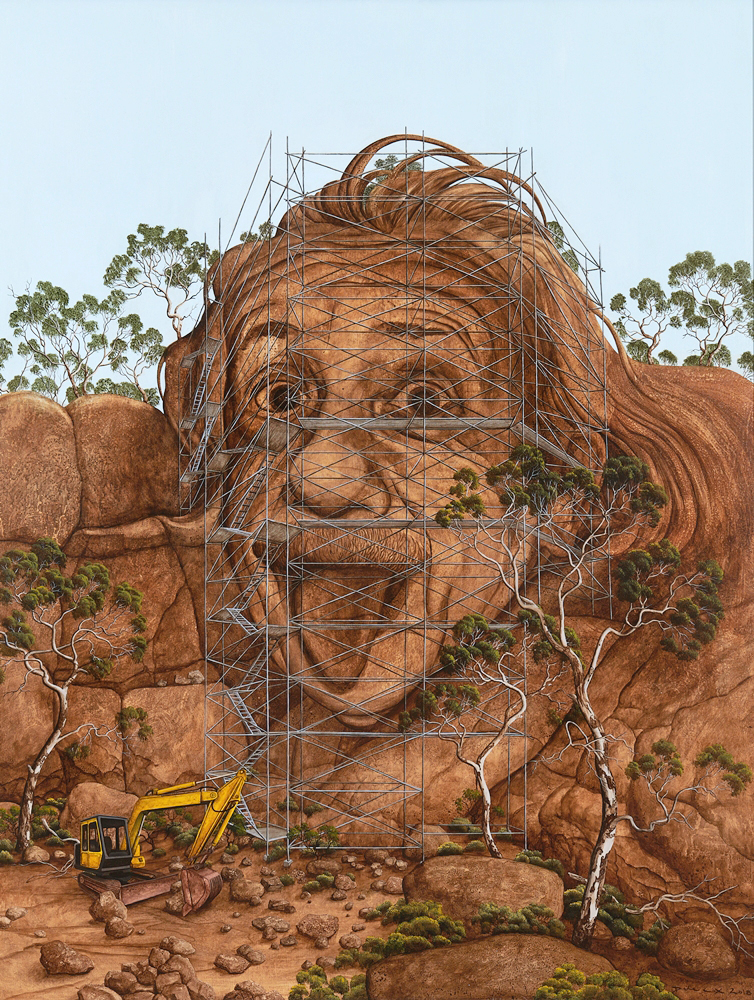

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

Albert

2018

Acrylic on board

160 x 122cm

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

The wonder of you

2018

Acrylic on board

120 x 90cm

Dale Cox (Australian, b. 1969)

The wonder of you (detail)

2018

Acrylic on board

120 x 90cm

Australian Galleries

35 Derby Street,

Collingwood 3066

Phone: +61 3 9417 4303

Opening hours:

Open 7 days 10am – 6pm

![Rex Hazlewood (Australian, 1886-1968) '[Men drinking billy tea]' 1911-1927 Rex Hazlewood (Australian, 1886-1968) '[Men drinking billy tea]' 1911-1927](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/hazelwood-billy-tea.jpg)

![James Fox Barnard (Australian, 1874-1945) '[Tea on the verandah]' c. 1900 James Fox Barnard (Australian, 1874-1945) '[Tea on the verandah]' c. 1900](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/barnard-tea-verandah.jpg?w=754)

You must be logged in to post a comment.