Exhibition dates: 7th April – 7th July 2013

Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990)

Every African must show his pass before being allowed to go about his business. Sometimes check broadens into search of a man’s person and belongings

1960-1966

Gelatin silver print

8 11/16 x 12 5/8 in. (22 x 32cm)

Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

Ernest Cole: Journeys through photojournalism, social documentary photography and art

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Abstract

This text investigates the trajectory of the work of Ernest Cole in order to understand how it developed under the influence of the South African Apartheid system.

Keywords

Ernest Cole, photography, photojournalism, social documentary photography, South Africa, apartheid, The Family of Man, photo book, photo essay, Drum magazine, Life magazine, art, House of Bondage.

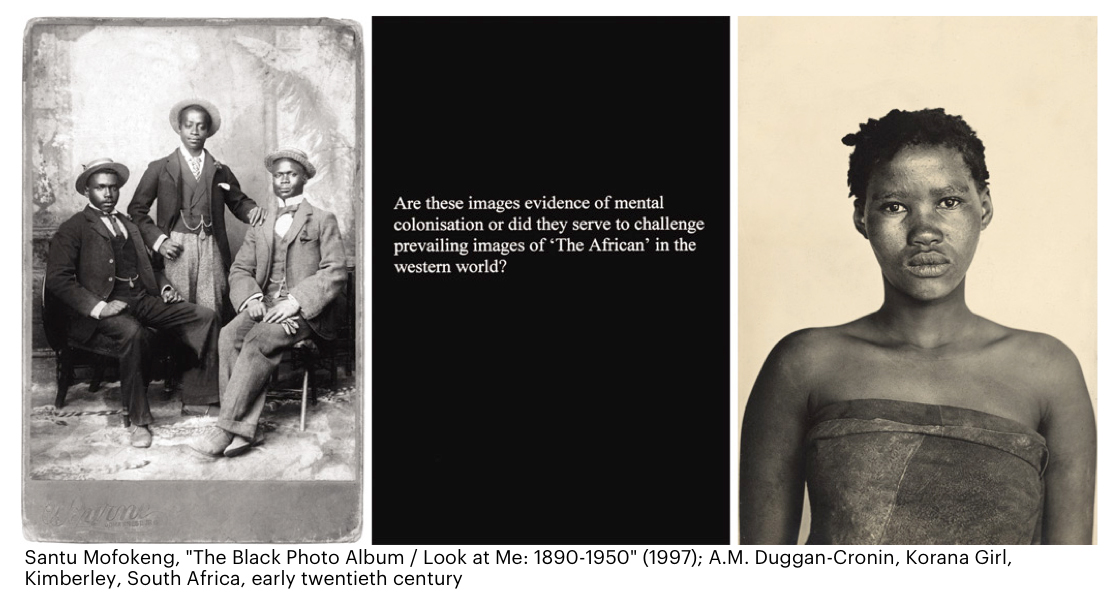

“For each individual photographer, there was the struggle to overcome the blind spots resulting from an internalised apartheid ideology. To see what had not hitherto been seen; to make visible what had been invisible; to find ways of articulating through the medium of photography, a reality obscured by government propaganda.”

Joyce Ozynski 1

“The Whites are more oppressed than the blacks in this country. Because they can’t feel. They have lost their humanity.”

Omar Badsha 2

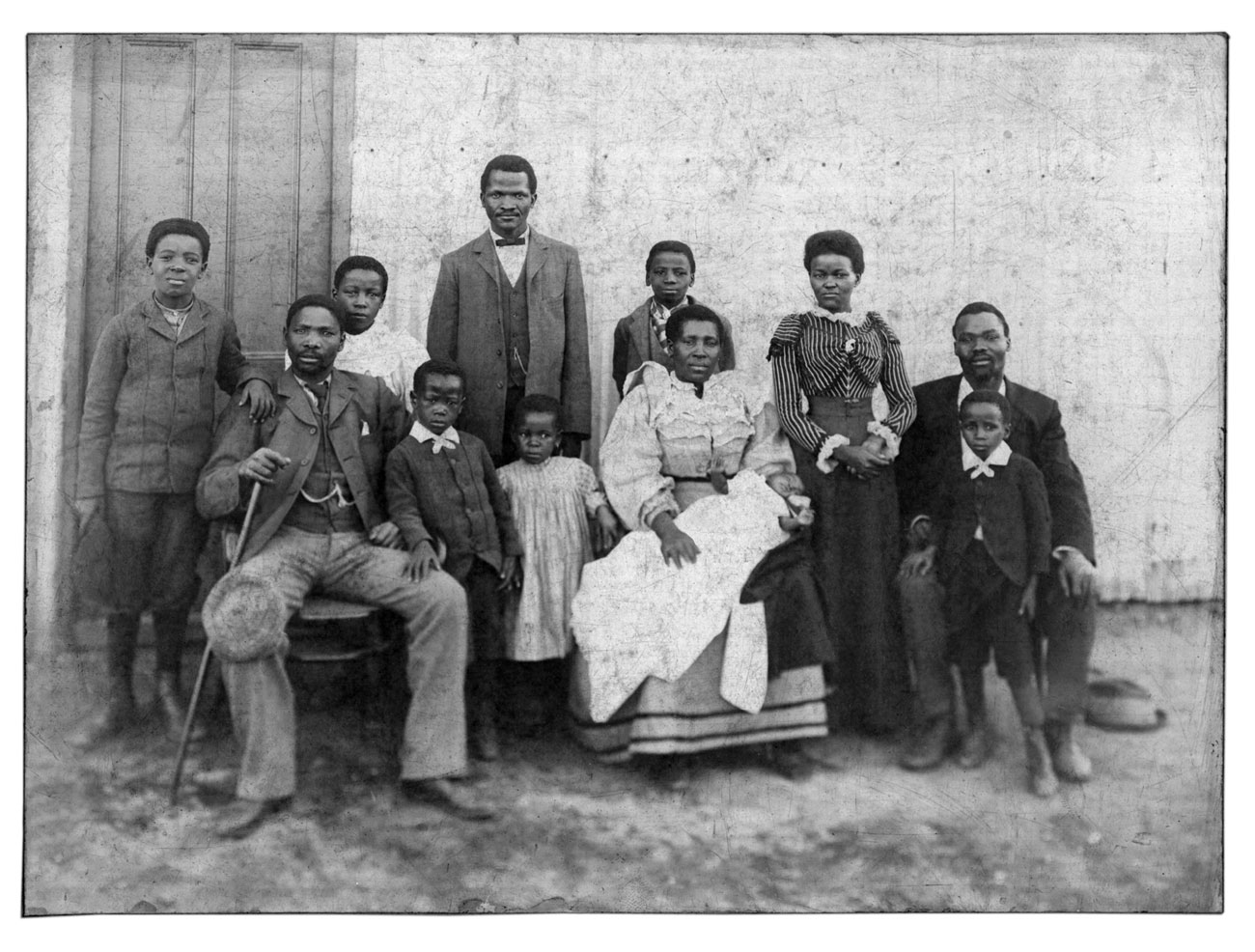

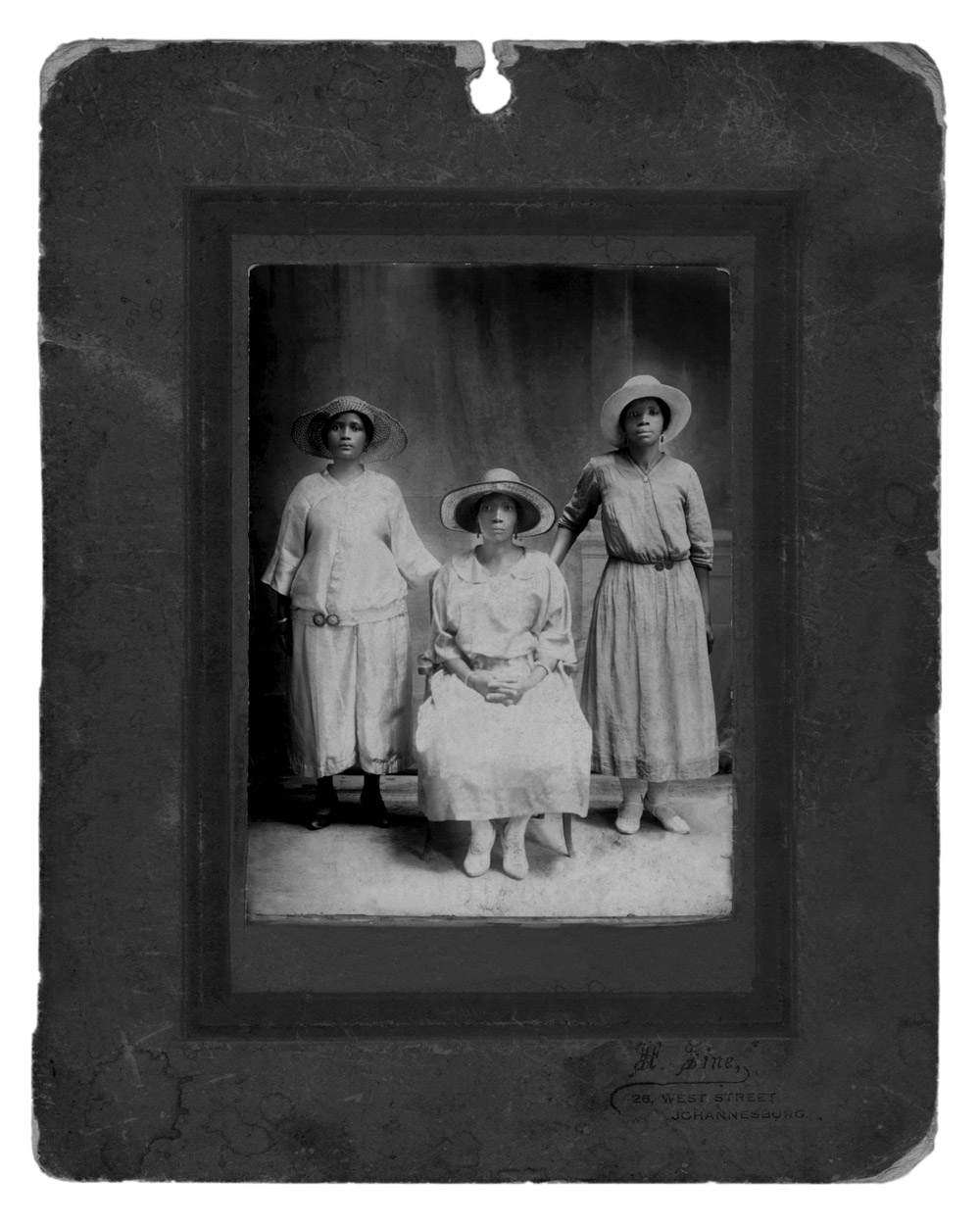

For 43 years (1948-1991) the country of South Africa and its people lived under the racially discriminatory policy of apartheid (separateness), adopted when the National Party (NP) took power and enshrined segregation laws between black and whites into law. Under these laws the rights of the majority black inhabitants of South Africa were curtailed and white supremacy / Afrikaner minority rule was maintained. The population was split into four groups: “native”, “white”, “coloured”, and “Asian”, and residential areas were segregated, sometimes by means of forced removals.3 One man who grew up under this oppressive regime and whose photographic representation of its nature made him a world-renowned photographer was Ernest Cole.

The photographer that we know as Ernest Cole was born Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole on the 21st March 1940 in humble circumstances, the fourth of sixth children, in Eersterust, an Eastern suburb of Pretoria. Cole suffered from malnutrition growing up, was slight of build (he was only 5′ tall as an adult) but was very intelligent. He took a series of menial jobs after leaving school at the age of 16, all he could find as an unskilled labourer. At the weekends during the 1950s, Cole began taking photographs on a black box camera and obtained a job as a dark room assistant to a Chinese photographer, later becoming photographer at Zonk magazine, a competitor to Drum magazine that he eventually joined as page layout designer and photographer in 1958.4

Drum magazine, founded as The African Drum in 1951, was the most influential magazine for black people during the anti-apartheid era, “A Magazine for Africa by Africa” that was loosely based on the template of the American Life magazine. Cole would have been exposed to international photojournalism through its pages; he also studied photography by correspondence course with the New York Institute of Photography and was always carrying around photography books that he avidly studied.5 Although few photographs by Cole were published to illustrate photo-essays in Drum (the photographs always appearing with accompanying text), he was exposed to the work of other photojournalists who appeared in its pages; he would also have seen the article that appeared in Drum in May 1958 on the international touring exhibition curated by Edward Steichen titled The Family of Man. This exhibition opened in Johannesburg in September 1958, and Cole would have certainly have visited the “no colour bar” post-war humanist photography exhibition.6 Darren Newbury’s chapter on the history of Drum in his excellent book Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa (2009) situates the magazine, “in the context of developments in international photojournalism and the rise of picture magazines in Europe and the US, while acknowledging the influence that urban black culture had on its style and content, with its concentration on US sportsmen and jazz music as well as stories on crime and poverty.”7

Here we observe the difference between photojournalism and social documentary photography. Photojournalism differs from social documentary photography in the primacy of text, the limited number of photographs, the more rigid conventions of framing, and the more direct form of highlighting injustice and inhumanity in resistance photojournalism.8

“Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism (the collecting, editing, and presenting of news material for publication or broadcast) that creates images in order to tell a news story… [and] is distinguished from other close branches of photography (eg. documentary photography, social documentary photography, or street photography) by complying with a rigid ethical framework which demands that the work is both honest and impartial whilst telling the story in strictly journalistic terms.”9 When compared to photojournalism, social documentary photography, “is the recording of humans in their natural condition with a camera. Often it also refers to a socially critical genre of photography dedicated to showing the life of underprivileged or disadvantaged people.”10

Cole, eventually unsettled by the piecemeal approach of taking single photographs to illustrate photo-essays in Drum – in other words being a photojournalist – moved towards being a social documentary photographer, inveigling himself of the history of this form of photography through the work of artists such as Jacob Riis, Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and the photographers of the Farm Security Administration (FSA).11 With his two 35mm Nikon cameras slung over his shoulder, Cole accessed areas that were usually restricted to black people because he had been classified as “coloured.” Being a loner, he could move about the city and country more freely than most black people who required identity passes, or “dompas” (“stupid passes”), to enter white areas. The work was dangerous and fraught with difficulty for when photographing in hospitals, prisons and mines, fear of discovery and arrest was ever present: paranoia and adrenalin were always part of this mix. Cole was frequently arrested and had, on occasion, to bury his negatives to hide them from the Secret Police. “He seemed to be able to get in anywhere and shoot anything, short and neat, in sports coat and slacks, he was the invisible man.”12

In one sense Cole’s photographs can be seen to have a relationship to “scene of the crime” photographs (such as those by Weggee),13 for Cole “steals” his images from the continuum of time, whipping out his camera, framing the image, snatching its import and returning the camera to the dark before anyone has noticed. Unlike Weggee, who used flash to capture his nightmarish scenes (making the presence of the photographer part of the psychology of the picture), Cole eschewed the use of flash. He was also an insider photographing a subject matter that was of great importance to him, not an outsider looking in at the subject, like the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson whose book People of Moscow was a great influence on the construction of his own book (see footnote 15).

Cole had a vested interest in recording the injustices and violence perpetrated on his fellow human beings by the white minority, representing in forensic detail as chronicler the travails of his people, for he was working toward a book that would document the condition of black people under apartheid, ultimately to be titled House of Bondage (1967). “He believed passionately in his mission to tell the world in photographs what it was like and what it meant to be black under apartheid, and identified intimately with his own people in photographs. With imaginative daring, courage, and compassion, he portrayed the full range of experience of black people as they negotiated their lives through apartheid.”14

Cole was like a spy, unobtrusively capturing his images and through the subtleties of composition and framing, making them art. “Considered both compositionally and in terms of the moment that is captured on film, what is most remarkable about them… and it is true of much of Cole’s work – is how elusive Cole, as photographer, remains within the unfolding dramas he documents.”15 He gathered the pictures for his meta-narrative in fourteen parts, House of Bondage,16 by photographing in the midst of the subject, registering “that climate of fear and loathing – the bondage – that is the subject of his work at the deepest level, in the way he goes about making his pictures.”17 His images have a level of documentary detail and narrative point that give them an immediate presence and the spaces within have an inescapable discomfort about them. “The sense is of the specific image as just one moment within a continuum of discomfort, resignation and suffering, encircling the photographs from all sides.”18

You feel what he feels, in the midst of, from inside. For example, look at the photograph Penny baas… (1960-1966, below) and just feel the explosive slap on the face of the boy begging, his right leg raised by the force of the casual yet sadistic blow, the other lad at left still holding his hands out pleading for a few tossed coins, enough to buy a small amount of food to ward off starvation. The photograph makes all right minded people angry but it also makes you complicit as well. The distinction between viewer and the subject being photographed is elided, as the viewer is propelled into the maelstrom of oppression and survival that is the apartheid state (of being).

In 1966, Cole was forced to leave South Africa or face becoming an informer or doing prison time, after being arrested with a gang of petty criminals he was photographing. His work was smuggled out of the country by international photojournalists and friends and his book, House of Bondage, was eventually published in New York in 1967. It was immediately banned in South Africa and Cole was never to return, passing away of cancer, homeless, penniless after more than 23 years of painful exile, leaving few negatives and prints of his monumental work. House of Bondage would expose the daily humiliation of the regime and achieve considerable success in the West, despite being banned in South Africa. Darren Newbury notes in Defiant Images that, “the tone of Cole’s book… was distinct from the photographic humanism which dominated Drum. Despite moments of human intimacy and humour, there is a sense of bitterness and anger.”19

Newbury goes on to observe that in House of Bondage Cole moved away from the photographic humanism that took root in South Africa in the 1950s, and which provided the initial context for Cole’s photographs. “House of Bondage moved in the opposite direction, representing the refraction of these ideas through the lens of apartheid South Africa and their return to the West. Read in this way House of Bondage is an antidote to Steichen’s Family of Man.“20 In other words, Cole was a photographer who transformed one visual language into an artistic language all his own – one not abrogated on Western ideals – as an affirmation of his own existence and his ability to create a body of work in spite of persecution, arrest, harassment and the restrictions of apartheid. He then returned that vision to the West.

Working secretively from inside the system, constantly under surveillance but almost invisible to it, Cole’s art explores the cracks, weaknesses, ambivalences, aporias and hypocrisy of the apartheid system, insinuating himself into the inner duplicities of its rationalisms.21 As he moves deftly through the spaces of the city taking photographs, Cole’s art transcends the inhospitality of that setting.22 As Newbury observes, Cole eschewed the romantic image of Johannesburg focusing instead on apartheid’s distortion of African culture. He created a damning visual critique that can also be read as a commentary on international humanist photojournalism itself. His was no naïve record.23

F(r)ame of reference, point of view

“By repositioning [Roman] Vishniac’s iconic photographs of Eastern Europe within the broader tradition of social documentary photography, and introducing recently discovered and radically diverse bodies of work, this exhibition stakes Vishniac’s claim as a modern master.”

International Center of Photography Adjunct Curator Maya Benton 24

With the current global interest in South African photography (which includes Distance and Desire: Encounters with the African Archive Part 1-3, a major exhibition program focusing on late nineteenth / early twentieth century African photography from The Walther Collection; Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life at Haus der Kunst, Munich; and South Africa in Apartheid and After: David Goldblatt, Ernest Cole, Billy Monk at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art all in 2012-13) – the viewing public has to be made aware of the curatorial interpretation of Ernest Cole’s photographs and seminal work, House of Bondage. As his fame spreads and becomes legendary, we must understand how his photographs can be interpreted across a range of frames of reference – from photojournalism, to social documentary photography and art.

Speaking to Nicholas Henderson, archivist at the Melbourne office of the National Archives of Australia,25 he made the point that the interpretation of Cole’s photographs becomes problematic depending on what frame of reference one applies to them and how their interpretation is negotiated between these multiple, fluid points of view. As can be seen in the quote above by Maya Benton, repositioning an artist’s work within a broader context changes the nature of the interpretation of the work and raises the pertinent question: who is repositioning the work and for what reason(s); who is pushing what agenda and curatorial barrow (in Benton’s case it is because she wants Vishniac’s work to be seen as that of a modern master, to make the import of the exhibition and the artist more than it possibly is).

Personally I believe that Cole’s work moves between all three frames of reference (fields of existence) – photojournalism, social documentary photography and art – with feeling (hence the quote by Omar Badsha at the beginning of this text). His work frames the historical discourse of apartheid in the past, present and future. What we must make ourselves fully aware of is the danger he placed himself in to make the work and the conditions for its initial reception – the era of mid-1960s global politics: the Cold War, civil rights movement in America, Vietnam War, gay liberation, era of free love, etc. “With imaginative daring, courage, and compassion, he portrayed the full range of experience of black people as they negotiated their lives through apartheid.”26

Speaking of the black American photographer Gordon Parks, Dr Henry Louis Gates has said, “Long after the events that he photographed have been forgotten, his images will remain with us, testaments to the genius of his art, transcending time, place and subject matter.”27 The same can be said of the art of Ernest Cole.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

July 2013

Word count 2,316

Endnotes

1/ Ozynski, Joyce quoted in Oliphant, Andries and Vladislavic, Ivan. Ten Years of Staffrider. Johannesburg: Raven Press, 1988, p. 163

2/ Badsha Omar. Transcript of a conversation between Chris Ledechowski and Omar Badsha, 11/1985, 1 on Anon. “Photography and the Liberation Struggle in South Africa,” (academic paper) on South African History Online website [Online] Cited 13/04/2013

3/ Anon. “Apartheid in South Africa,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 13/04/2013

4/ Robertson, Struan. “Ernest Cole in the House of Bondage,” in Knape. Gunilla (ed.,). Ernest Cole Photographer. Hasselblad Foundation/Steidl, 2010, p. 23

5/ Ibid., p. 24

6/ Newbury, Darren. “‘Johannesburg Lunch-hour’: Photographic Humanism and the Social Vision of Photography,” in Newbury, Darren. Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa. Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2009, pp. 55-56

7/ Lowe, Paul. “Review of Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa,” on Times Higher Education website, 22nd July 2010 [Online] Cited 13/04/2013

8/ Anon. “Photography and the Liberation Struggle in South Africa,” (academic paper) on South African History Online website [Online] Cited 13/04/2013

9/ Anon. “Photojournalism,” on the Wikipedia website [Online] Cited 13/04/2013

10/ Anon. “Social documentary photography,” on Wikipedia [Online] Cited 13/04/2013

11/ Anon. “Farm Security Administration,” on on Wikipedia [Online] Cited 13/04/2013

12/ Robertson, Struan. “Ernest Cole in the House of Bondage,” in Knape. Gunilla (ed.,). Ernest Cole Photographer. Hasselblad Foundation/Steidl, 2010, p. 35

13/ Powell, Ivor. “A Slight Small Youngster with an Enormous Rosary: Ernest Cole’s Documentation of Apartheid,” in Knape. Gunilla (ed.,). Ernest Cole Photographer. Hasselblad Foundation/Steidl, 2010, p. 41

14/ Press release on the exhibition South Africa in Apartheid and After: David Goldblatt, Ernest Cole, Billy Monk on the SFMOMA website, 1st December 2012 – 5th March 2013

15/ Powell, Op. cit., p. 41

16/ House of Bondage contains 183 photographs organised thematically into 14 sections, each beginning with between two and five pages of text. The section titles give a sense of the underlying political and sociological analysis: ‘The Mines’, ‘Police and Passes’, ‘Black Spots’, ‘Nightmare Rides’, ‘The Cheap Servant’, ‘For Whites Only’, ‘Below Subsistence’, ‘Education for Servitude’, ‘Hospital Care’, ‘Heirs of Property’, ‘Shebeens and Bantu Beer’, ‘The Consolation of Religion’, ‘African Middle Class’ and ‘Banishment’. How the final decision on the number and titles of sections was arrived at may be unknowable, but the idea for a thematic structure of this kind was undoubtedly Cole’s. This is clear not only from the New York Times pieces, but also reflects the book that Cole cited as one of the determining influences on his photography: Cartier-Bresson’s People of Moscow.

Newbury, Darren. “An ‘Unalterable Blackness’: Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage,” in Newbury, Darren. Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa. Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2009, pp. 187-188

17/ Powell., p. 41

18/ Ibid., p. 44

19/ Newbury, Darren. “An ‘Unalterable Blackness’: Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage,” in Newbury, Darren. Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa. Pretoria: Unisa Press, 2009, p. 174

20/ Ibid., p. 175

21/ Ekpo, Denis. “Any European around to help me talk about myself? The white man’s burden of black Africa’s critical practices,” in Third Text 19(2), 2005, p. 17

22/ See Caldwell, Marc. “Look Again, What Do You See?” in Journal of Southern African Studies 38(1), 2012, pp. 241-243

23/ Newbury Op. cit., p. 207

24/ Press release from the exhibition Roman Vishniac Rediscovered at the International Center of Photography (ICP), New York, January 18, 2013 – May 5, 2013

25/ Conversation with the author, Sunday 7th April 2013

26/ Press release on the exhibition South Africa in Apartheid and After: David Goldblatt, Ernest Cole, Billy Monk on the SFMOMA website, 1st December 2012 – 5th March 2013

27/ Dr Henry Louis Gates quoted in the press release from the Gordon Parks: Centennial exhibition at the Jenkins Johnson Gallery, February 21 – April 27, 2013

Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990)

“Penny, baas, please baas, I hungry…” This plaint is part of nightly scene in Golden City, as black boys beg from whites. They may be thrown a coin or, as here, they may get slapped in the face

1960-1966

[Caption from House of Bondage]

From House of Bondage Period

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990)

Africans throng Johannesburg station platform during late afternoon rush

1960-1966

Gelatin silver print

8 11/16 x 12 5/8 in. (22 x 32cm)

Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990)

After processing they wait at railroad station for transportation to mine. Identity tag on wrist shows shipment of labor to which man is assigned

1960-1966

Gelatin silver print

8 11/16 x 12 5/8 in. (22 x 32cm)

Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust

Ernest Cole (1940-1990), one of South Africa’s first black photojournalists, passionately pursued his mission to tell the world what it was like to be black under apartheid. With imaginative daring, courage and compassion, he portrayed the lives of black people as they negotiated apartheid’s racist laws and oppression. Ernest Cole Photographer – on view at the Fowler Museum from April 7 – July 7, 2013 – brings 113 original, extremely rare black-and-white silver gelatin prints from Cole’s stunning archive to the United States for the first time.

Inspired by the photo-essays of French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, Cole documented scenes of life during apartheid from 1958–66. He captured everyday images such as lines of migrant mineworkers waiting to be discharged from labor, a schoolchild studying by candlelight, parks and benches for “Europeans Only,” young men arrested and handcuffed for entering cities without their passes, worshippers in their Sunday best, and crowds crammed into claustrophobic commuter trains. Together with Cole’s own incisive and illuminating captions, these striking photographs bear stark witness to a wide spectrum of experiences during the apartheid era. Ernest Cole Photographer is the first major public presentation of Cole’s work since the publication of his book, House of Bondage, in 1967. A large majority of the images are shown for the first time in the way Cole had originally intended – uncropped and accompanied only by his minimal remarks. These images of apartheid are astonishing not only for their content but also their formal beauty and narrative power.

About the artist

Ernest Cole was born March 21, 1940, in the black freehold township Eersterust, east of Pretoria. The son of a tailor and a laundry woman, Cole grew up in the countryside where he stayed with an aunt. For high school, he re-joined his parents in the township where he was born. He became interested in photography as a teen, and landed a position in Johannesburg as a darkroom assistant at DRUM magazine in 1958. There he began to mingle with other talented young black South Africans – journalists, photographers, jazz musicians, and political leaders in the burgeoning anti-apartheid movement – and became impassioned in his political views.

In the mid-1960s Cole set out at great personal risk to produce a book that would communicate to the rest of the world the corrosive effects of South Africa’s apartheid system. Working in areas continually patrolled by police forced Cole to become covert in his approach: he smuggled his camera into prisons and mines inside a lunch bag, used a long lens to photograph from a distance, and even fooled the apartheid bureaucracy into reclassifying his racial identity as “coloured,” or mixed race, thus providing more freedom to move around towns and cities.

In 1966 Cole was arrested along with a group of petty thieves whom he had befriended in order to document their lives and means of survival. The police discovered Cole’s fraudulent identity and offered him two options: join their ranks as an informer, or be punished for fraud. Cole quickly left South Africa for Europe and took with him little more than the layouts for his book. His photographs and negatives were separately smuggled out of the country shortly after.

Cole’s project was realised in 1967 when Random House in New York published House of Bondage, a graphic and hard-hitting exposé of the racism and economic inequalities that underpinned apartheid. Although House of Bondage was banned in South Africa, contraband copies circulated and played an important role in shaping South Africa’s tradition of activist photography that emerged in the succeeding decades.

Uprooted from his home and community and divorced from the circumstances that had fired his creative imagination, Cole never found his feet in Europe or America. He died homeless in New York in 1990 after more than twenty-three years of painful exile, never having returned to South Africa and leaving no known negatives and few photographic prints.

Tio fotografer, an association of Swedish photographers with whom Cole had worked when he lived for a short time in Stockholm, received a collection of Cole’s work that was later donated to the Hasselblad Foundation. In 2006 eminent South African artist David Goldblatt received a major award from the Hasselblad Foundation and urged them to make their Ernest Cole collection accessible through a book and an exhibition.

Press release from The Fowler Museum at UCLA website

Drum magazine

Shadow over Johannesburg

October 1951

Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990)

Earnest boy squats on haunches and strains to follow lesson in heat of packed classroom

1960-1966

[Caption from House of Bondage]

From House of Bondage Period

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990)

Handcuffed blacks were arrested for being in white area illegally

1960-1966

[Caption from House of Bondage]

From House of Bondage Period

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990)

Pensive tribesmen, newly recruited to mine labour, awaiting processing and assignment

1960-1966

From House of Bondage Period

© The Ernest Cole Family Trust Courtesy of the Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden

The Fowler Museum at UCLA

North Campus of UCLA, Los Angeles

CA 90024, United States

Phone: +1 310-825-4361

Opening hours:

Monday – Tuesday Closed

Wednesday – Sunday 12.00 – 5.00pm

The Fowler Museum at UCLA website

LIKE ART BLART ON FACEBOOK

Back to top

![Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990) 'Untitled [White Washroom]' 1960-1966 Ernest Cole (South African, 1940-1990) 'Untitled [White Washroom]' 1960-1966](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/19_cole_untitledwhitewashroom-web.jpg?w=650&h=926)

You must be logged in to post a comment.