Exhibition dates: 17th June – 2nd October, 2022

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Eight photo booth self-portraits)

Nd

Gelatin silver prints on whiteboard

Sheet: 8 × 9 1/2 in. (20.32 × 24.13 cm)

Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate

Ray Johnson was an American artist “known primarily as a collagist and correspondence artist, he was a seminal figure in the history of Neo-Dada and early Pop art…” He absorbed from his teachers Josef Albers, Alvin Lustig, and Robert Motherwell and “entered into Zen kinship with two teachers, John Cage and Merce Cunningham, and into romantic partnership with another, the sculptor Richard Lippold.” And then he burnt all the early paintings in his possession and took the path less trodden. He developed his own artistic language “through the creation of slight, irregular-shaped, frame-resistant (but mailable) collages he called “moticos”.” (The name was an anagram of the word “osmotic”)

After moving from New York to Locust Valley, Long Island in 1968, Johnson continued to make art but only had two more solo exhibitions, the last one in 1991. “Johnson was forever constructing miniature sets for his own delirious theatre of the absurd: puzzles within puzzles. The sensibility is not unlike Joseph Cornell’s [whose work was a major influence], minus the romance and period nostalgia. Johnson worked in another sort of outsider vernacular – at once banal, vulgar, campy, and deeply sophisticated.”1 The curator Joel Smith refers to “the low-key but constant thrum of odd motivation” behind all of the artist’s work.

Towards the end of his life Johnson took up photography and became a master of the throwaway camera, using the machine to create intimate, staged actions “which served the artist as a form of citation: as a way to “reference,” rather than “represent,” his subjects. The hands-off nature of the medium gave Johnson a way to bring topics up yet keep his viewer (his recipient, his reader) focused on something he cared about more: the messaging process itself.”

Each person, each artist has a different reason to communicate. But what are they communicating? In Johnson’s case I think he was expressing his inner alternate reality, a different point of view of the world communicated through a new and fantastical visual language. Inhabited by bunnies and pop stars, Johnson’s work was a collage of the unclassifiable, bizarre, wired, wonderful, pop, performance, licked, action, nothings, dreams, concept, sexual, stamped, eccentric and enigmatic moticos… osmotic and fluidly subversive observational images, staged interventions, obsessive, witty and weird constructions. As Loring Knoblauch observes, “these pictures find new pathways of physical intervention, creating staged installations that combine Johnson’s restless collage combinations and the quirks of photographic vision into something cleverly unexpected.”2

Revelling in his insider-outsider status, Johnson was a naive draftsman / Navy draftsman (he loved a good play on words). There is a “distinctive wit – and the evident delight of discovery – that runs through these photographs.” But it is a dark witticism, as dark one of my favourite movies, Donnie Darko (full of bunnies). His is art as performance… of nothings, of everything, moving everything, setting everything in motion. We follow his in/actions whether it be documenting a flopped stranger wearing a bunny cutout, six Movie Stars in the back of a car, or his prescient undated Eight photo booth self-portraits (above) in which he acts out and obscures different personas.

In his last performance this creative man of nothing (real life) “was seen jumping from a bridge in Sag Harbor… [and] appeared to be doing a backstroke toward the open Atlantic.” He could not swim. As he said of one of his early performances, it (he) “went off into the void in some marvellous fashion…”

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Vince Aletti. “A Trove of Snapshots from a Sly Master of Collage,” on The New Yorker website July 22, 2022 [Online] Cited 26/09/2022

2/ Loring Knoblauch. “PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs @Morgan Library,” on the Collector Daily website September 7, 2022 [Online] Cited 26/09/2022

Many thankx to the Morgan Library & Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Johnson, however, was a prankster. Like the bunny head he adopted as his trademark – a cartoonish line drawing that appeared in much of his work, often bearing the name of a key figure in 20th-century art – he hopped lightly, merrily across this playing field. Revelling in puns and irreverence (an untitled 1973 collage known as “Jackson Pollock Fillets” includes cut-out recipes for Pollock Fillets Amandine and Barbecued Pollock Burgers), conducting his life as a nonstop performance, he revived the Dada tradition embodied by his hero Marcel Duchamp. In contrast to the grandiosity of Minimal art, land art, Pop Art and other macho midcentury movements, he offered something much humbler: collages or drawings of portable size and wry wit. … Johnson created some of the earliest works of Pop Art and was an early influence on conceptual art. …

The contents of Johnson’s pictures fall into several categories. At times, he chopped up the photos and used them to form a collage. Usually, though, and more interestingly, he found or created a collage-like pattern within the photographic frame. He made corrugated cardboard pieces that he called movie stars, and carried them to places where he could photograph them. Sometimes they incorporated images of celebrities: Marilyn Monroe, Jack Kerouac, Johns. Often they were renditions of his signature creation, a bunny with long, erect ears and a pendulous nose that, like a “Kilroy was here” graffiti drawing from World War II, feels both childlike and sexualized. He would inscribe a bunny with a name, thereby transforming it into a standardized personal portrait. And then he would drive his movie stars to a picturesque setting and shoot them with his camera.

Arthur Lubow. “An Elusive Artist’s Trove of Never-Before-Seen Images,” on The New York Times website March 23, 2021 [Online] Cited 26/09/2022

As a body of work, these photographs by Johnson absolutely feel unfinished, in an open-ended and unwieldy way, as though he was grasping for new ways to communicate. Seen together, there is both dogged teach-yourself inventiveness and a hint of loneliness on display, with a nostalgia for stars of the past and his own younger face percolating through his iterative reworkings. At their best, these pictures find new pathways of physical intervention, creating staged installations that combine Johnson’s restless collage combinations and the quirks of photographic vision into something cleverly unexpected. At the end of his life, Johnson was actually becoming an interesting photographer, and these unearthed leavings provide tantalizing glimpses of what might have been.

Loring Knoblauch. “PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs @Morgan Library,” on the Collector Daily website September 7, 2022 [Online] Cited 26/09/2022

Overview

Dubbed “New York’s most famous unknown artist” by the New York Times, Ray Johnson (1927-1995) was a widely connected downtown figure, Pop art innovator, and pioneer of collage and mail art. After moving from Manhattan to suburban Long Island in 1968, Johnson selectively distanced himself from the mainstream art world, holding only two exhibitions after 1978. Yet even after his last show, in 1991, he remained a prolific and unpredictable artist.

Johnson used photographs in his work for decades, but it was only with his purchase of a single-use, point-and-shoot camera in January 1992 that he embarked on his own “career as a photographer.” By the end of December 1994 he had used 137 disposable cameras. His most frequent subjects were what he called his Movie Stars: meter-high collages on cardboard, often featuring the bunny head that served as his artistic signature. They became ensemble players in the curious tableaux he staged in everyday locales near his Locust Valley home.

At his death by suicide in January 1995, Johnson left a vast archive of art in boxes stacked throughout his house, including over five thousand colour photographs, still in the envelopes from the developer’s shop. This body of work, virtually unseen until now, comprised his final major art project, the last act in a romance with photography that had begun some forty years earlier.

PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs

A widely connected pioneer of Pop and mail art, Ray Johnson (1927-1995) was described as “New York’s most famous unknown artist.” Best known for his multimedia collages, he stopped exhibiting in 1991, but his output did not diminish. In 1992-1994, he used 137 disposable cameras to create a large body of work that is coming to light only now. Staging his collages in settings near his home in Locust Valley, Long Island – parking lots, sidewalks, beaches, cemeteries – he made photographs that pull the world of everyday “real life” into his art. In his “new career as a photographer,” Johnson began making collages in a new, larger format that made them more effective players in his camera tableaux. The vast archive he left behind at his death included over three thousand of the late photographs. Now, his final project makes its debut alongside earlier photo-based collages and works of mail art: fruits of a romance with the camera that spans the four decades of the artist’s career.

Hazel Larsen Archer (American, 1921-2001)

Ray Johnson at Black Mountain College

1948

Gelatin silver print

13 3/4 × 9 7/8 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum

Purchased as the gift of David Dechman and Michel Mercure

© Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer

As a student at North Carolina’s Black Mountain College from 1945 to 1948, Johnson thrived under the rigorous tutelage of his foundation-course teacher Josef Albers (1888-1976). Johnson also modelled for Archer, a fellow student who would go on to teach photography at the school. This portrait – lush, faceless, and sexually ambiguous – foreshadows the complexity of Johnson’s use of photography throughout his career. Though attracted by the camera’s peerless ability to bestow glamour, he often tried to undercut its role as a transparent conveyor of facts.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

RJ silhouette and wood, Stehli Beach

Autumn 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

As an artist, Johnson was a master hunter-recycler, constantly revisiting and reinterpreting images from his past. On a visit to the beach at nearby Oyster Bay in 1992, he brought along a camera and a cardboard cutout of his head. Propping the board against a piece of driftwood log, he created a visual pun: the log’s central rings evoke the swirl of hair that Hazel Archer had once photographed on his (now long-bald) head.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Moticos with KAFKAYLLA)

c. 1953-1954

Collage on illustration board

13 × 5 in. (33.02 × 12.7cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Johnson applied one all-purpose noun, “moticos” (both singular and plural), to his short writings, his collages, and the glyph-like shapes he drew. He and his friend Norman Solomon coined the term by reshuffling the word “osmotic,” chosen out of the dictionary. On this moticos made from a flattened box, Johnson paired a photograph of a pigeon with its strange twin: a sort of photo-bird, composed of cookie cutters and a checkerboard. Johnson proposes a second unlikely duo by combining the names of the author Franz Kafka (1883-1924) and the photographer Ylla (Camilla Koffler, 1911-1955), known for her images of animals.

Moticos

In the autumn of 1955, artist Ray Johnson walked through the streets of New York City with a slip of paper, asking strangers if they could define the word he’d written on it: “motico.” People gamely racked their brains: “‘Gee, I wish to hell I knew,’ said one. A nun asked, ‘Isn’t it a kind of colour?'” Johnson recalled these encounters in a story that ran that year in the very first issue of The Village Voice, when he was 27 years old and living in Manhattan, and working primarily in painting and collage.

The word was one Johnson had invented. An anagram of osmotic (a word allegedly chosen at random from a book), “moticos” could refer to several different things. Johnson called the small collage panels he made “moticos” but he also used the word to refer to textual representations too. Johnson would paint and transform the cardboard pieces that came with his laundry into parts of his collages, transforming them into silhouettes and then glyphs, new moticos.

Rebecca Bengal. “Photo Dump: Digging into the 5,000 Photographs Ray Johnson Left Behind,” on the Elephant Art website 20 Jul 2022 [Online] Cited 25/09/2022

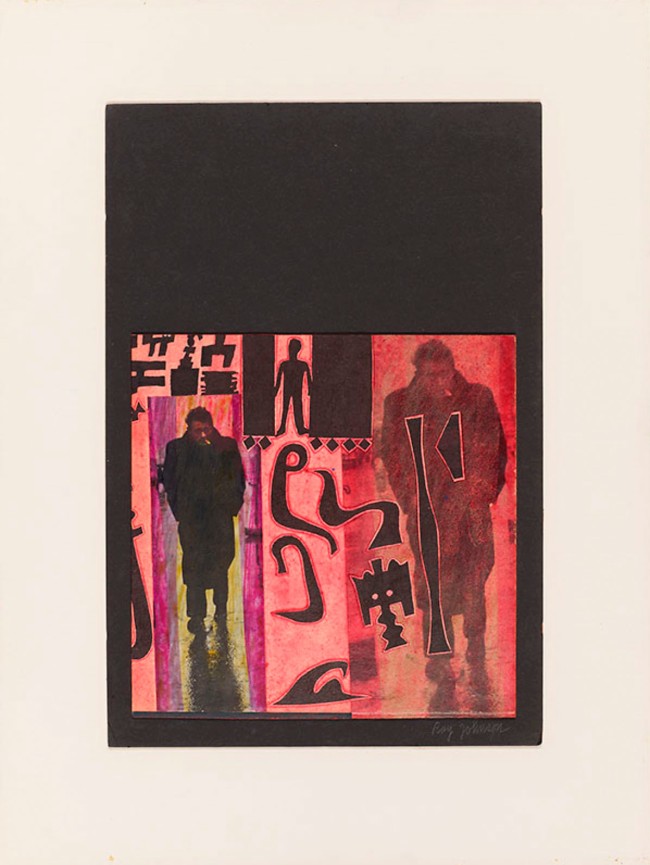

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (James Dean in the Rain)

c. 1953-1959

Collage on illustration board

15 1/2 × 11 3/4 in. (39.37 × 29.85cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

From the early 1950s, Johnson embraced photocollage as a way to inject Hollywood glamour into the cloistered world of avant-garde art. He was appropriating mass-media imagery years before Andy Warhol began populating monumental canvases with celebrity portraits. Here Johnson worked directly upon Dennis Stock’s iconic Life magazine photograph of James Dean walking alone through Times Square, which was published a few months before Dean died in a 1955 car crash. Whether Johnson made this work before or after Dean’s death is unknown. In the 1990s, he would again incorporate the actor’s silhouette in collages and photographs.

Elisabeth Novick

Untitled (Moticos on floor)

c. 1955

Gelatin silver print

8 3/4 × 13 1/4 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

Elisabeth Loewenstein / ArenaPAL

© Elisabeth Loewenstein

For a short feature in the first issue of the Village Voice (26 October 1955), a reporter walked with Johnson as he approached strangers in Grand Central Terminal and asked them whether they knew what a “moticos” was. As seen here, Johnson also literally took moticos to the streets, staging crowds of them for the camera in disused spaces in downtown Manhattan. Few early moticos have survived intact: over the next several decades, in a practice he called Chop art, Johnson continually disassembled his work and used the fragments to create new pieces.

Elisabeth Novick

Untitled (Ray Johnson and Suzi Gablik)

1955

Gelatin silver print

11 × 14 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

Elisabeth Loewenstein / ArenaPAL

© Elisabeth Loewenstein

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

1955 moticos photographs from ladder

January 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 inches

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1955 Johnson asked his friend Elisabeth Loewenstein (later Novick) to bring a camera along on a walk with their mutual friend Suzi Gablik (1934-2022). Novick’s photographs record the impromptu performance that ensued, in which Johnson draped moticos on Gablik’s face and body. A fellow Black Mountain College alum, Gablik would become an influential critic; in her 1969 book on Pop art, she described improvised actions such as this one as the first “informal happenings” – ephemeral events conceived as works of art – in the postwar era.

Johnson preserved the photographs Novick made that day. Nearly forty years later, in one of his earliest experiments with a “throwaway camera,” he laid out the prints in a grid on his driveway and photographed them from atop a ladder.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Correspondence to Frances X. Profumo

Undated

Typewritten text on paper, newspaper clippings

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the mid-1950s, Johnson simultaneously shifted from oil painting to small-scale collage and from gallery exhibitions to the mail as a way of putting his art before an individual viewer. An envelope from Johnson often contained enigmatic clippings from books and magazines, including photographic illustrations drawn from the same stockpile that fuelled his collages. These are items Johnson sent in the 1950s to Frances X. Profumo, whom he befriended when he was a student and she an employee at Black Mountain College. The many visual and textual Xs invoke both Profumo’s distinctive middle initial and the convention of signing a fond letter “with kisses” (XXX).

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Nothing with Brancusi)

Undated

Ink on book page

9 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (24.13 × 19.05cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Mapplethorpe with moticos)

Undated

Ink on magazine page

Image: 7 × 7 in. (17.78 × 17.78cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (book page with umbrella as splint)

Undated

Ink on paper

Image: 9 1/2 × 7 in. (24.13 × 17.78cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Over the years, Johnson inducted hundreds or thousands of recipients into what he called the New York Correspondence School by mailing them oblique yet personalised messages. These altered book and magazine pages were among the unmailed works found in his house after his death.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Offset printing plate (Ara Ignatius portrait)

c. 1964

Metal

Image: 15 1/2 × 10 in. (39.37 × 25.4cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Ara Ignatius portrait with a photograph of lips)

Undated

Cut paper on paper

Image: 11 × 8 1/2 in. (27.94 × 21.59cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Ara Ignatius portrait with bunnyheads)

Undated

Ink on paper

Image: 11 × 8 1/2 in. (27.94 × 21.59cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Johnson favoured likenesses that masked as much about him as they revealed. He repeatedly used a headshot that his friend Ara Ignatius made around 1963. It is an unnerving image, lacking the conceit of intimacy that characterises most formal portraits; instead it “stands for” Johnson, in the artless manner of a government-issued ID.

Many pieces of mail art that look like photocopies are in fact products of offset printing – a means of transferring photographs and other images to the page from reusable metal plates. The medium allowed Johnson to return to an image repeatedly, imposing variations that reflected his ever-changing purposes.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (“I shot an arrow into the air…” with Shirley Temple and Vikki Dougan)

c. 1970-1972

Ink, wash, collage, vintage photograph on illustration board

18 × 15 in. (45.72 × 38.1cm)

The Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In this photocollage, two movie actors meet: Vikki Dougan (b. 1929), who became a sex symbol in the 1950s by publicly appearing in backless dresses, and the quintessentially innocent child star Shirley Temple (1928-2014). Temple’s rendering as a blacked-out, moticos-like figure may allude to her adult married name, Shirley Temple Black. Across the bottom of the image, a line from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1845 poem “The Arrow and the Song” is altered to refer to Johnson’s forerunner in collage and assemblage art, Joseph Cornell (1903-1972), who lived in Flushing, Queens.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

David Hockney’s Mother’s Potato Masher

1972-80-88-94

Collage on cardboard panel

20 3/8 × 15 1/4 in. (51.75 × 38.74cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of Frances Beatty, Alexander Adler, and the Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The title of each collage in the Potato Masher series begins with a notable artist’s or celebrity’s name. The titles then take an abrupt turn away from stardom by alluding first to the famed figure’s mother, and then to her potato masher. Here, Johnson included his own likeness in the form of a headshot, made around 1963 by the photographer Ara Ignatius. His face is covered by black moticos and cut-up fragments of his earlier artworks. Johnson created his collages over a span of weeks, months, or even years, dating each element in pencil as it joined the composition.

The Morgan Library & Museum presents PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs, opening June 17 and running through October 2, 2022. This exhibition explores the previously unknown camera work of the widely connected downtown New York figure, Pop art innovator, and pioneer of collage and mail art. At his death on 13 January 1995, Ray Johnson (1927-1995) left behind a vast archive of art in his house, including over five thousand colour photographs made in his last three years. Small prints, neatly stored in their envelopes from the developer’s shop, the photographs remained virtually unexamined for three decades. Now they can be seen as the last act in a romance with photography that had begun in Johnson’s art some forty years earlier. After retracing the story of Johnson’s use of photography throughout his career, PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE offers an in-depth look at the late work the artist called “my career in photography.”

After moving from Manhattan to suburban Long Island in 1968, Johnson selectively distanced himself from the mainstream art world, holding only two exhibitions after 1978. Yet even after his last show, in 1991, he remained a prolific and unpredictable artist. With his purchase of a single-use, point-and-shoot camera in January 1992, he embarked on an entirely fresh creative enterprise. By the end of December 1994, he had used 137 disposable cameras. His most frequent subjects were what he referred to as his Movie Stars: meter-high collages on cardboard, often featuring the bunny head that served as his artistic signature. They became ensemble players in the curious tableaux he staged in everyday locales near his Locust Valley home.

As an artist, Johnson was a master hunter-recycler, constantly revisiting and reinterpreting images from his past. He appears to have first used a disposable camera for a practical purpose: documenting his enormous backlog of unused collage fragments. He performed that work in his driveway and on the back steps of his house, but soon he was carrying a pocket-size camera on daily outings to nearby beaches, parks, and cemeteries. Johnson’s photographs exhibit a collagist’s instinct for insertion, layering, and surprise: most of them are centred on objects that he placed between himself and a scene as he found it. In his photographs as in his pun-filled writing and his densely worked collages, Johnson used juxtaposition to suggest that everything finds correspondence in something else. The point-and-shoot habit gave him a way to create an image almost as quickly as he could think of it. As curator Joel Smith writes in the book that accompanies the exhibition, “Nowhere in Johnson’s art does he look more intensely engaged by the present tense, more thrilled to be immersed in real life, than in the inventions of his throwaway camera.”

“PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE offers a rare chance to examine photographs taken by Ray Johnson, an artist known primarily for his brilliant work in collage,” said Colin B. Bailey, Director of the Morgan Library & Museum. “The images, most of which have gone unexplored until now, are truly innovative and ahead of their time. The exhibition also celebrates a significant gift of Johnson’s work, generously made by Ray Johnson estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.”

“These photographs show that in his last years, Ray Johnson remained irrepressibly, explosively creative,” said Smith, the Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Morgan. “It’s his last great body of work, and its very casualness is prophetic: ten years later, smart phones and social media turned daily life into a constant exchange of personal photographs and commentary. Johnson was still making collages right up to the end – but now he made them in a camera, and the ‘real life’ all around him was his medium.”

PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs is accompanied by a book with the same title published by Mack Books, which includes an essay by the exhibition’s curator, Joel Smith.

Press release from the Morgan Library & Museum

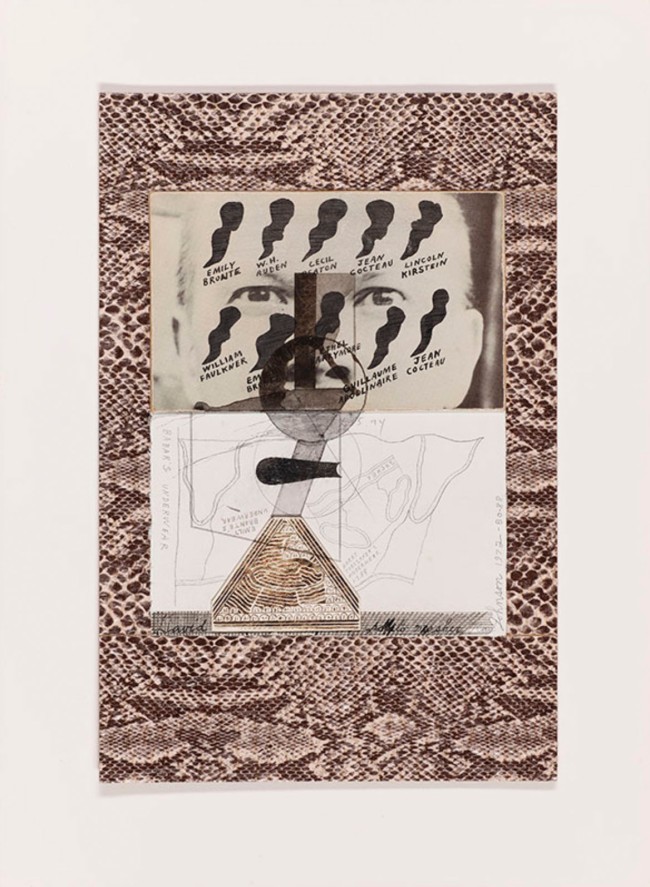

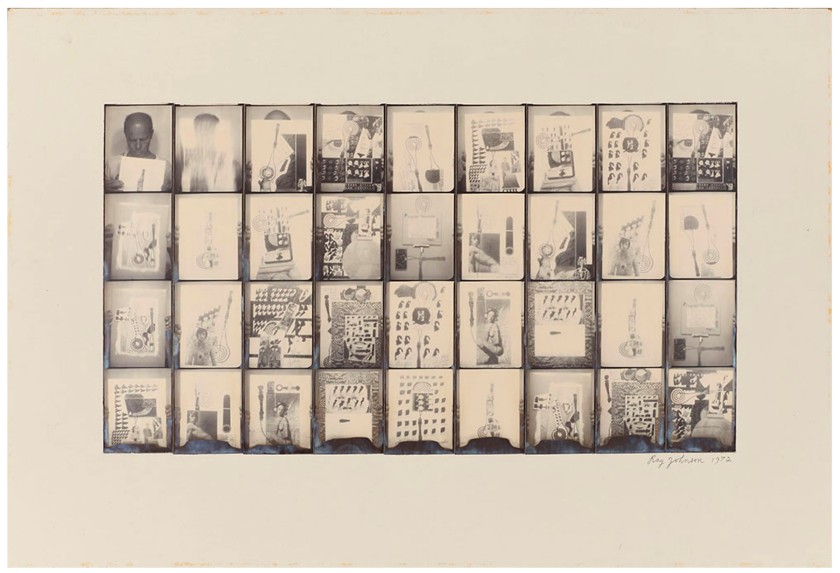

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Photo Booth Collage)

1972

Collage on illustration board

12 7/8 × 19 in. (32.7 × 48.26cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of Frances Beatty, Alexander Adler, and the Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Here, Johnson (visible at top left) employs a booth as an affordable studio for documenting works from his Potato Masher series. Sitting in the photo booth, he simply held up one collage after another for the automatic camera. The resulting sequence of vertical photo strips combines the qualities of a crude performance document and an art gallery’s inventory sheet. David Hockney’s Mother’s Potato Masher appears, not yet finished, fourth from the left in the bottom row.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

William S. Burroughs silhouette and kingfisher

Winter 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gifts of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Tab Hunter William Burroughs)

c. 1976-1981

Collage on cardboard panel

12 × 12 1/2 in. (30.48 × 31.75cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of Frances Beatty, Allen Adler, Alexander Adler, and the Ray Johnson Estate

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1976 Johnson began asking friends, art-world figures, and celebrities to sit and have their silhouettes traced onto paper. He thus built a library of nearly three hundred profile templates he could use and reuse. As a portrait form, the silhouette reduces its subject to a graphic shape, identifiable but resistant to psychological interpretation. In this example, Johnson overlapped the profiles of 1950s movie heartthrob Tab Hunter (1931-2018) and avant-garde writer William S. Burroughs (1914-1997).

In the 1990s Johnson photographed one of his stock props, a stuffed kingfisher, in combination with Burroughs’s silhouette. The beak of the bird extends the author’s prominent nose: a bill replacing the bill of a Bill.

Even when Johnson avoided direct self-portraiture, his quirky fixations were always evident. (In an essay for the exhibition catalogue, the curator Joel Smith refers to “the low-key but constant thrum of odd motivation” behind all of the artist’s work.) In one of the collages on display, William Burroughs’s profile nearly eclipses that of the nineteen-fifties movie star turned gay icon Tab Hunter, and both are all but obscured by a swarm of pebble-like fragments and bits of collage. Johnson was forever constructing miniature sets for his own delirious theatre of the absurd: puzzles within puzzles. The sensibility is not unlike Joseph Cornell’s, minus the romance and period nostalgia. Johnson worked in another sort of outsider vernacular – at once banal, vulgar, campy, and deeply sophisticated. Like John Baldessari, he favored artless lettering and crisp graphic design. The cardboard slats, especially, might be mistaken for portable Baldessaris.

Vince Aletti. “A Trove of Snapshots from a Sly Master of Collage,” on The New Yorker website July 22, 2022 [Online] Cited 26/09/2022

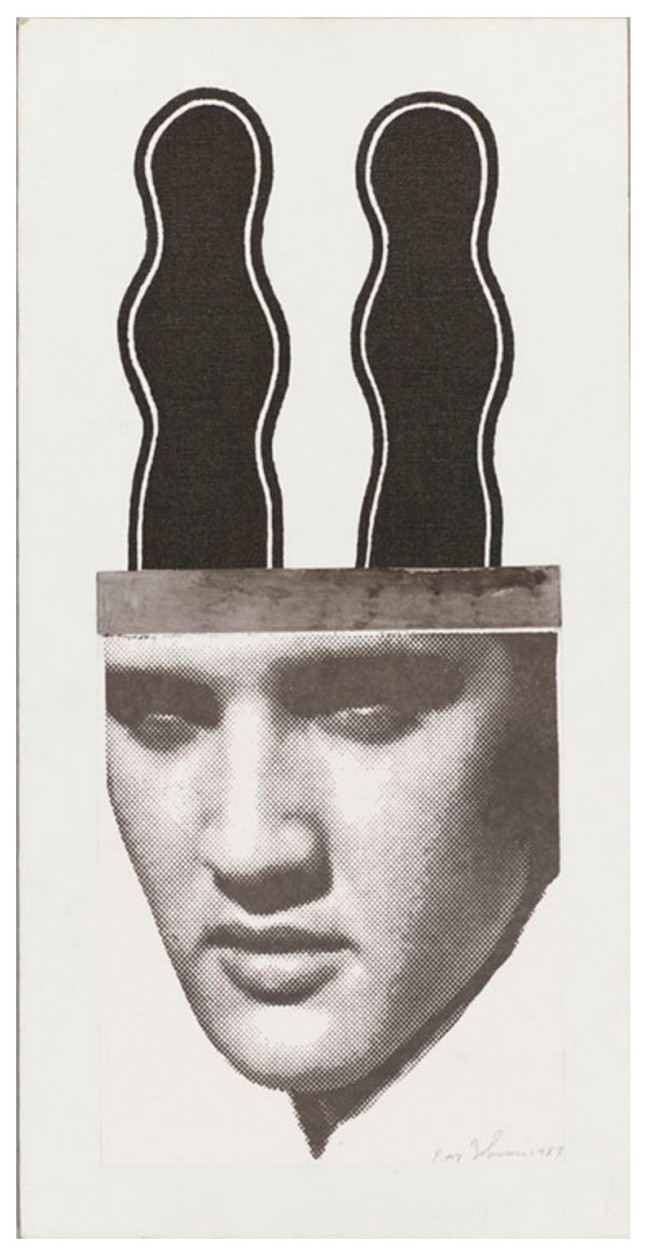

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Elvis with Bunny Ears)

1987

Collage with acrylic and ink on canvasboard

16 × 8 in. (40.64 × 20.32cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty.

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Beginning in the 1950s, Johnson made artistic use of photographs of the twentieth-century cultural icon Elvis Presley (1935-1977). Johnson’s most emblematic motif, a stylised bunny face, first appeared beside the artist’s name in 1964. Bunny ears would serve both as a kind of trademark and as a way of turning anyone – Elvis, in this case – into a Ray Johnson character. The enlarged halftone dots that compose Elvis’s image confirm its status as a mass-market photographic reproduction.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Rubble and photo credit

Summer 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

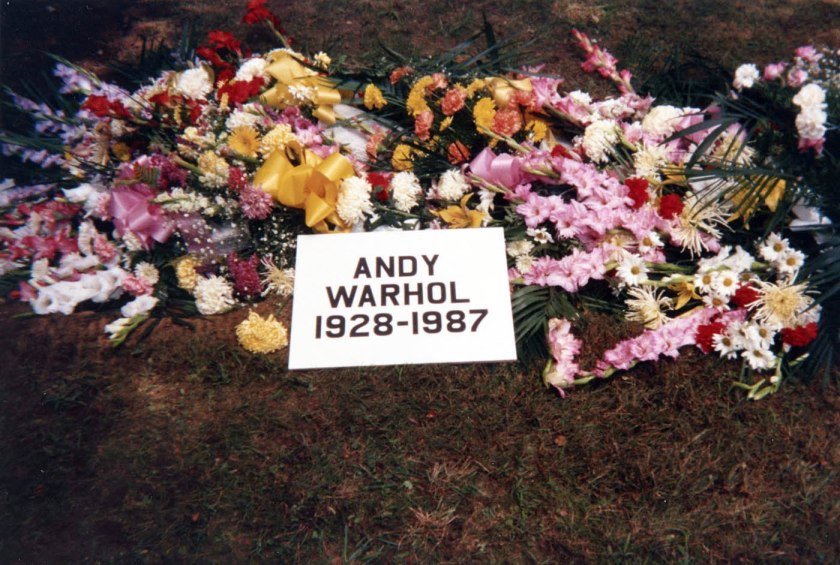

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Andy Warhol life dates on flowers

July 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Shadow and manhole

Spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Johnson appears to have first used a disposable camera for a practical purpose: documenting his backlog of unused collage fragments. But in January 1992, he told curator Clive Phillpot, “I’m pursuing my career as a photographer,” and in March he added, “I’m having fun with my throw-away camera.” Always faithful to the rapidity of his own thinking, Johnson found in the “throwaway” Fuji Quicksnap a way to give graphic form to ideas as they occurred to him.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Path of headshots and back steps

Spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Joseph Cornell silhouette and payphone

Spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Bills, Stehli Beach

Summer 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6

The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty; 2022.2:11

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Johnson’s first photography studios were the driveway and back steps of his house, but soon he was carrying a pocket-size camera on his daily outings to nearby beaches, parks, and cemeteries. In spring 1992, he threaded a cutout silhouette of Joseph Cornell over the cord of a payphone, then photographed it with one hand while holding the receiver with the other – acting as operator of a hotline to the collage-art pioneer.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

One-legged figure beside back steps

Spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Mondrian’s grave and playing card, Mount Lebanon Cemetery, Queens

spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Billboard

Summer 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Even in his photography, Johnson exhibits a collagist’s instinct for insertion and layering. Most of his photographs are centred on objects that he placed between himself and a scene as he found it. On occasion, though, he used the camera in a conventional way, simply collecting views of sights that drew his interest, such as a billboard advertising nothing or the word HELP on the underside of a boat. Photographs such as these are the field notes of a minutely attentive observer.

PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE

Joel Smith

In January 1992, a few weeks after his last lifetime exhibition closed at Moore College in Philadelphia, the artist Ray Johnson began photographing in and around his house in Locust Valley, Long Island, using what he called “my throwaway camera”: a single-use point-and-shoot, preloaded with daylight color film. Thirty-five months and 137 throwaways later, he photographed views through the storefront window of an even-more-final exhibition called Ray Johnson: Nothing. It was up during the Christmas week lull of 1994 in a gallery on the main street of Sea Cliff, a few minutes’ drive from Johnson’s house, and around the corner from that of his friend and frequent mail-art partner, Sheila Sporer. Then, one Friday a couple of weeks into 1995, a man was seen jumping from a bridge in Sag Harbor, an hour and a half’s drive east. Witnesses reported that Johnson – the body, when recovered, proved to be his – appeared to be doing a backstroke toward the open Atlantic. (He could not swim.) Johnson’s presumed suicide is often described as the final work of a career in which art and life had long been inseparable.

In his last three years Johnson made and mailed art incessantly, went out for a drive most days, and ran through about one camera a week. When he finished a twenty-four-frame roll, he would drop off the camera – he used a couple of Kodaks at first and then, consistently, Fujicolor Quicksnaps – at Living Color, a shop in Glen Cove, for developing and printing. After turning sixty-five in October 1992, he often took advantage of a senior discount and ordered duplicate prints. For some forty years his art practice had consisted mainly of collage, relief assemblages, and correspondence art. Though photographs had figured in all three channels of work, they were not photographs made by Johnson himself, but portraits of him by others, or images he cut out of books or magazines. Now, in what he called his new “career as a photographer,” Johnson incorporated a few of his own photographs in modest little collages. He also mailed his photographs to correspondents, usually in the form of photocopies. But in the season after his death, among the dozens of boxes of art and effects Johnson left packed up in every room of his house, over five thousand of the color photos were found, still filed with their negatives and receipts in Living Color envelopes. To say the photographs were found needs qualifying: their existence was recorded, but years would pass before photography registered as a central creative pursuit of his final years.

It is not surprising that this work evaded scrutiny. Physically, these are plain, consumer-grade four-by-six-inch color snapshots, indistinguishable from those anyone would take home from the processor’s – whereas Johnson’s art more often took the form of distinctly, peculiarly altered public imagery. After the rise and canonization of Pop art in the 1960s, his work of a few years earlier, notably his addition of dripping red tears to a fan-magazine photo of Elvis Presley (1956-1957), looked prescient. Johnson, like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, took mass-market imagery for his muse – but, instead of enlarging it to grandiose scale, his instinct was to bestow the status of an artistic “original” upon ordinary, available-to-everyone printed matter itself. His collages, in that sense, define an antipode to Pop painting’s monumentalised appropriations. His prototype, you could say, was the sardonic teenager he had been not long before, scribbling mustaches onto Marilyns in magazines.

Spend time with the color photographs, and Johnson’s playful, punky persona becomes evident – not in anything he did to the pictures, but in their contents. The straight-men in these images are the streets, beachfronts, and parking lots of bucolic, smalltown northern Long Island: Locust Valley, Sea Cliff, Roslyn, Lattingtown, Glen Cove, Bayville. The scribbled mustaches are the dramatis personae Johnson introduces to those spaces. Within a few months of starting his photo-work, he began making, and photographing, collages on what were, for him, large (thirty-two-by-eight-inch) pieces of corrugated cardboard (62). (The cardboard often bears Fuji brand info; it, too, comes from the camera shop, or out of its dumpster.) In a letter to art critic David Bourdon in summer 1993, Johnson introduces ninety-three of these collages by name (Bobby Short, Greta Garbo …) and calls them his Movie Stars (or Move Stars). Indeed, despite their rectilinear format, they read as figures: paper-doll play-actors for his photo-tableaux. They have faces – most frequently Johnson’s signature pop-eyed, schlong-nosed bunny, inscribed with a name or phrase. (Many of those are rendered in mirror letters, correctly sequenced but laterally FLOPPED, as if in a misbegotten effort to address a reader on the other side of a steamy window.) As he did with his collages generally, Johnson would glue new elements onto these figures over time, dating each newly added bit in pencil. As the weeks of photo-shoots roll by, you can watch as a figure that starts as mostly naked cardboard fills up with information. I picture Johnson exiting his little grey house (he described its color as “grey with an e,” but named it The Pink House) with a freshly worked batch of Movie Stars under his arm, loading them into the back of his Volkswagen Golf, and taking them out on a drive, camera in pocket.

About a decade after these photographs were made, smart phones came into use, and everyone began having a camera on their person all the time. In 1992, making a photograph still required deciding and preparing to do so, and not simply asking oneself (or not even asking), “Why don’t I?” Buying the camera, noting how close to frame zero it was getting, dropping it off, returning to pick up the prints: making these pictures called for effort, on a par with the effort of crafting the Movie Stars. The whole enterprise reflects the low-key but constant thrum of odd motivation that drives all of Johnson’s work. The art he made was irreducibly personal, if gnomic, and he went to lengths to maintain control over how his collages, punning defacements, paradoxes, and near-nothings would make their way into the world. Johnson’s New York Correspondence School – the vast network he invented for circulating mail art – existed mainly in his head, but this, from his angle, made it no less real than the art world.

In the art-historical fairy tale of postwar New York City, young Ray Johnson must have looked, for a few years, like an avant-garde heir apparent. Born in 1927, the only child of loving working-class parents, he grew up in Detroit and, from 1945 to 1948, attended North Carolina’s Black Mountain College, crucible of every far-seeing artistic impulse of that moment. He was shy and hard-working and he devoured all he could from instructors who included Josef Albers, Alvin Lustig, and Robert Motherwell. He left BMC having entered into Zen kinship with two teachers, John Cage and Merce Cunningham, and into romantic partnership with another, the sculptor Richard Lippold. The four of them took up residence in a building in the deep reaches of downtown Manhattan. Johnson earned money working in Ad Reinhardt’s studio and at the Orientalia bookstore. He showed his Albers-sized, minutely rendered geometric paintings as a member of the American Abstract Artists group. In short, he seemed destined for middling highbrow success.

Instead, he became Ray Johnson. Between 1954 and 1956, he ditched his qualifications by burning all the early paintings still in his possession and redirecting his creative effort onto the slight, irregular-shaped, frame-resistant (but mailable) collages he called “moticos.” His move to print-media-based figural collage came at an historical moment far too late to boast a Dada-Surrealist pedigree and too early to get swept neatly up into Pop. The concerted wrongness of this switch makes it, in retrospect, quietly brilliant, and it points to the singularity that doomed Johnson’s crown-prince prospects. (Two of his successors and friends at BMC, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, picked up those prospects and put them to good use.)

Johnson hung onto a number of photographs that documented his fateful conversion. At age sixty-four he arranged twenty of them in a grid on the drive behind his house, then scaled a ladder to re-photograph them (26). In most of these old photographs, moticos in profusion can be seen arrayed in two real-world sites, a pallet on a sidewalk and a large industrial interior. In others – which were made in the street by a friend of Ray’s, the future fashion photographer Elisabeth Novick (then Loewenstein) – you can see Johnson draping moticos all over another friend (and fellow BMC alum), Suzi Gablik. These are, in effect, performance records; Gablik even came to describe Johnson’s moticos-stagings as perhaps the first Happenings in art—a notion that arguably proceeds from their having been photographed. Interviewed in 2015, Novick emphasized how casually this came about. Not long before, she had been given her first camera, and one day, Ray simply asked her to bring it along on a walk. “Suzi just sat there,” Novick said, “and he just threw the things on top of her.” She explains: “He was a very lighthearted sort of whimsical person. […] He wasn’t intense. It was the opposite of intense. If I could look up the opposite word of intense, I would say that was him.”

The “opposite-of-intense” mode of hardly-work Johnson was auditioning that day led him to an art based on play, exchange, and movement; on remaining light-footed enough to follow any association that came to mind, be it ever so slight, silly, or hermetic. Perhaps for just that reason, Johnson’s art found its ideal helpmate in the camera, with its knack for lending graphic form to the ephemeral. In any event, the 1955 documents turn up repeatedly in his color photographs of forty years later (44, 102).

Even more prevalent in these images is the infinitely malleable bunny head (64) that Johnson described as “a sort of self-portrait.” Its partner, equally ever-present, is a headshot of Johnson made by Ara Ignatius around 1963. (Johnson kept on hand an offset plate of this image, from which he could order new printings by the hundreds whenever he needed them.) In one early-1992 photograph, nineteen headshots are laid down in a path leading to Johnson’s backdoor stairs, where he would be staging many more photographs (20). In the summer of 1993, four headshots stare in through the windshield of his car, like a posse of avid fans (126). The headshot rides shotgun with Elvis (108) and, reduced to a pair of eyes, lends consciousness to a mob of moticos on camelback (98).

Johnson’s longtime collector, advocate, and chief interpreter, William Wilson, observed that photographs served the artist as a form of citation: as a way to “reference,” rather than “represent,” his subjects. The hands-off nature of the medium gave Johnson a way to bring topics up yet keep his viewer (his recipient, his reader) focused on something he cared about more: the messaging process itself. Using another photography adjacent tool, the silhouette, Johnson could convert the people he knew into references-to-themselves. Starting in 1976, he used pencil and paper to trace the profile shadows of some 284 sitters. He filed these in two big template binders, ready for use in the studio. Most of his profile subjects were writers, artists, and actors, whose shared characteristic is their publicly traded names.

Some of the silhouettes appear in the colour photographs, as do various celebrity portraits – but many more people show up as bunny faces inscribed with their names. Johnson wrote to Bourdon that seventy-two of his Movie Stars were going to appear in a “RAY JOHNSON OUTDOOR MOVIE SHOW” (see 110, 122, and 124 for variant stagings) that would stand “45 feet in length if ever actually placed next to each other and the wind didn’t blow them down.” In the meantime, he posed individual Movie Stars in the company of obliging strangers (54) or leaned them against the occasional dog (222).

The photographs include some one-offs, such as the shadow cast by Johnson’s mailbox (2) and a tar seam in a parking lot (176). Many of the subjects, though, are ones he revisited dozens of times, such as local beaches, cemeteries, and storefronts, a bathtub he found in a field (106, 107), and himself as a shadow, encountering a manhole cover (4).

Most of the photographs work in a collage-like way: they record Johnson’s alteration of a real-world setting through the addition of some flat thing he has made or chosen, such as one of his grimly cartoony black-on-white graphic characters, hiding amid spiky succulents (18), or an ace of clubs, leaning against Piet Mondrian’s grave marker (42).

At other times he works like a conventional photographer, observing but not intervening, as when he captures the horizon across Long Island Sound (230), a faceless billboard (41), the snapped arrow of a rooftop weathervane (16), or a palm frond splayed on beach sand (92).

Still other images define a mode between these two options, as Johnson finds some noteworthy thing to photograph (dragon’s teeth icicles [6], a mortuary angel [8]), then props up beside it a sign that emblazons the view like a maker’s logo or a graffitist’s tag: “PHOTO BY RAY JOHNSON”; “RAY JOHNSON THE PARIS CORRESPONDENCE SCHOOL.”

Here are a few of the subjects that kept Johnson and his 137 cameras coming back most often:

Inside. When Johnson photographed inside his house, the daylight-exposure film in his pre-loaded cameras restricted his work area to patches of direct sunlight. In late afternoon, the window in his front door cast a scalloped picture frame, or spotlight, around whatever he photographed on the floor (132, 168). The window’s shape in turn became a player, alone or in tandem with its mirror image (45).

Telephones. Johnson was as tireless a phone-caller as he was a mailer. Once, while at home, he held the phone for a bunny labeled EAR MUFS, posing between a 1955 photo and a clutch of moticos glyphs (28). Out driving around, he staged momentary installations in payphone boxes (65, 232). He unhooked one phone’s receiver and threaded over its cord a cardboard cutout silhouette of the artist Joseph Cornell, whom he used to visit in Flushing, Queens (12). The cutout void of Cornell’s head frames the telephone’s number-pad, turning Johnson into the operator of a Cornell-box hotline: camera in one hand, receiver in the other, plugged into the head of the master collagist.

Doubles. In Johnson’s universe, doubleness – correspondence – is the norm. No surprise, then, that he should photograph twins, replicas (48, 50), and those spellbinding autocopies, twin-initialed celebrities (Marilyn Monroe, Mickey Mouse [160]). He gives dualism a distinctly photographic turn by pairing things with their reflections or shadows. When photographed, these light-borne modes of doubling assume a concrete presence: they make reality look Johnsonian. A reflection echoes its original, but the two are non-identical. The reflection – being laterally flopped, like Johnson’s mirror letters – is the original’s opposite (52, 172). As for the shadow, it is a flat, graphic version of its original (70), an incorporeal counterpart to reality (136).

Recycling. A collagist traffics in the reincarnation of materials and images. The beginnings of Johnson’s photographs look like an effort to document his vast inventory of “chop art” – his term for the densely-reworked chunks of assemblage he had been building up and cutting apart again for decades (30-33). He abandoned this cataloguing, but his photographs remain as full of junk (130, 131) as his house (228); “WHAT A DUMP.” His movie-reel memory encompassed everything from Bette Davis films to a porn video made famous in the confirmation hearings of Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas [150]). He created a deadpan cardboard memorial to his old associate, arch-recycler Andy Warhol, and laid it atop a raked pile of cemetery flowers (142), and, two years later, atop a scattering of donated clothes (144).

Bills. Scavenged out of those clothing drops, most likely, were the many baseball cap visors Johnson photographed. He held them up before the camera, always in C formation, with deep spaces behind them: the sky, or receding railway tracks (34, 78). He arrayed them on Stehli Beach like a school of migrating horseshoe crabs (94). He cut the bill’s crescent-moon shape out of his headshot (33). If they stand for a name, “Bill,” perhaps he is William Wilson. Or the writer William S. Burroughs, who sat for his silhouette in 1976. Johnson laid a cutout of Burroughs down on cardboard, then extended Bill’s prominent nose with the bill of a kingfisher (96).

Photographers. The photographs feature many images drawn from photography’s historical canon, making Johnson-collaborators of, among others, Walker Evans (via Sherrie Levine) (136), Dennis Stock (158), and Félix González-Torres (186). Some Movie Star bunnies are given the names of photographers, including Horst, Duane Michals (154, 170), and Lord Snowdon (snowed-in / snowed-N [236]). The crane in Bill Brandt’s famous photograph of Kew Gardens provides the top half of an awkward composite figure (159, 174). Johnson perched Michals’s book of portraits on the front bumper of his car, making a third headlight of its cyclopean eye (138). He turned Richard Avedon’s An Autobiography face-down to reveal its author photo and dressed the portraitist in a hat (163) that channels Marianne Moore, who is portrayed in that book wearing her signature tricorn (a moticos-like garment that fascinated Johnson). Late one dusk, Johnson photographed the legs of his shadow spanning a copy of Lee Friedlander’s book Like a One-Eyed Cat, laid down open to its frontispiece, one of Friedlander’s many self-portraits in shadow (80).

Please Send. Between July and December 1994, over twenty wrapped packages appear in Johnson’s photographs. They are addressed to or from his mail-art correspondents, most frequently his local friend Sheila Sporer (158, 242). (The ones Sheila opened – those not marked “DO NOT OPEN” – turned out to be stuffed with plain craft paper.) Often the packages are pictured in the midst of what look like obscure rituals. One stands in Johnson’s driveway, tethered to a helium bunny balloon, ready to begin its physically impossible ascent (206). Others he positioned inside the gallery show-window of his late December 1994 un-show, Ray Johnson: Nothing, and then photographed them from out on the sidewalk (169). (He never ventured inside.) A few days later, he posed two packages, tourist-like, at the end of a pier at sunset (214); distressingly, one of them is next seen drifting in the water below (216).

In late December 1994, Johnson photographed himself in a shop window mirror, holding up a bunny inscribed PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE (246). (On the collage, this bunny bears the date December 21; below it, on December 30, Johnson added ONLY YOU [244].) REAL LIFE refers, at one level, to the New York-based art magazine REALLIFE (1979-1994): since late November, Johnson had been urging Sporer to pitch its editor, Thomas Lawson, an article about their three years of collaborative correspondence art.

But the message can mean something else, too – something like: “Here, Life, take this thing I’ve made; I’m going to the other place.” For decades death had been a resolute presence in Johnson’s work, taking such forms as Nothing, pitch-black humor, and a fixation on life dates. Is death palpably present in the photographs of his last three years? It would be silly to deny that it is. And yet it would be trivial to hunt through this large, complex, often comical, always personal body of work for nothing more than a rebus suicide note. Ray Johnson never made himself that easily readable. And nowhere in his art does he look more intensely engaged by the present tense, more thrilled to be immersed in Real Life, than in the inventions of his throwaway camera.

Joel Smith. “PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE,” in PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs. Mack Books, 2022, pp. 188-195

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Outdoor Movie Show on RJ’s car

February 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Outdoor Movie Show in RJ’s backyard

1 June 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

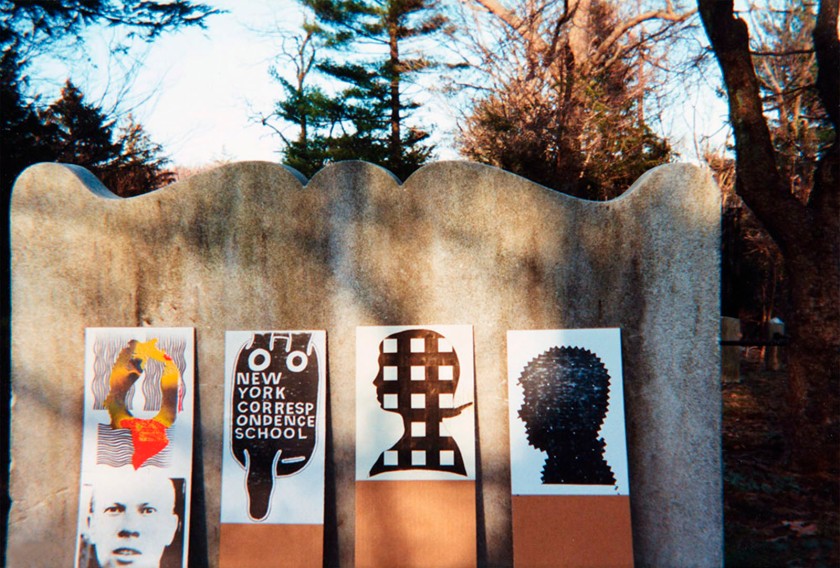

The photographs Johnson made between January 1992 and December 1994 feature several dozen collages in a large, vertical format he had never used before. He referred to these works as Movie Stars (or Move Stars), writing that “if the wind didn’t knock them down,” he planned to cast them in a “Ray Johnson Outdoor Movie Show,” lined up like dancers in a musical revue. In the end, still photography was the nearest he came to filmmaking.

In the same way that Johnson burned his early paintings, renouncing the most reliable route to a successful art career in mid-20th-century New York, he exited the fray of Manhattan. In 1968 he moved to Locust Valley, Long Island, and after 1978 he had only two solo exhibitions – the last one in 1991. He continued to make art, though, and looked to artists like Joseph Cornell, famous for his box assemblages, who lived on Utopia Parkway in Queens. Many of Johnson’s works take Cornell’s idea of the display box filled with quirky objects and expands it to tableaus staged for the camera, using the suburban environment, the woods or the seashore as found theatrical sets. …

Johnson’s presence in many of the photos could be called self-portraiture – but the photos also feel very much like ancestors to the ubiquitous cellphone selfie. The photo “RJ with Please Send to Real Life and camera in mirror” (1994) is an obvious selfie precursor. It includes a number of conceptual twists, however: Johnson appears in a mirror, holding a disposable camera and one of his cardboard signs with an alter-ego bunny and the words “Please Send to Real Life” partially printed in reverse – a reminder of how the camera doesn’t merely document reality, but shapes and potentially distorts it. (This photo might also be a reference to his mail-art practice or the New York art magazine Real Life, published from 1979 to 1994.) …

What is art? What is real? Does the image document reality or create it? “Please Send to Real Life” raises some of these questions and shows how Johnson predicted the growing fuzziness between the realms of photography and IRL (in real life) – from snapshots to social media – suggesting that the relationship between them is porous but also ripe for creative intervention.

Anonymous. “Ray Johnson’s Camera Was Disposable. The Photos Are Unforgettable,” on The New York Times website 24th August 2022 [Online] Cited 28/08/2022

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (yellow DUANE MICHALS bunny)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

13 3/4 × 4 1/2 in. (34.93 × 11.43cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (JOSEF ALBERS with cat)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

17 3/8 × 7 1/2 in. (44.13 × 19.05cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (six blue Rays in Rolls)

Undated

Collage on corrugated cardboard

21 × 8 1/2 in. (53.34 × 21.59cm)

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Movie Stars

Overhead are some of the several dozen collages that appear in photographs Johnson made between January 1992 and December 1994. He referred to these large, vertical pieces as Movie Stars (or Move Stars), writing that “if the wind didn’t knock them down,” he planned to cast them in a “Ray Johnson Outdoor Movie Show,” lined up like dancers in a musical revue. In the end, still photography was the nearest he came to filmmaking. Were the Movie Stars made to be photographed? Or are the photographs mere documents of the Movie Stars? Perhaps the two bodies of work are best understood as complementary parts of a continuous creative cycle. Many of the Movie Stars are made on cardboard that bears photographic product information, suggesting that it was scavenged from the dumpster of the shop where Johnson bought his cameras and turned them in for developing.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Cage and Satie with Orpheus and Eurydice, Planting Fields Arboretum

February 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Jasper John

February 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

WIGART grave and Movie Star of RJ between David Bs

April 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Movie Stars feature a roll call of celebrity faces and names that is, in composite, unique to Johnson’s imagination. By photographing the collages, Johnson animated his personal pantheon in the familiar settings of his daily life. Composers Erik Satie and John Cage rest in the arms of a statue of Orpheus, the prophetic music-maker of Greek myth. Artist Jasper Johns punningly marks the door of an outhouse-like wooden structure. Johnson himself rides shotgun in his Volkswagen Golf while Elvis takes the wheel. And art critic David Bourdon and rock star David Bowie (embodiments, in different ways, of Pop’s legacy) join Johnson at the grave of “Wig art.” Once Johnson even photographed the Movie Stars in their staging area at home, ready to be loaded into the car and taken out for a day’s work.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Headshot and Elvises in RJ’s car

February 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Outdoor Movie Show on dumpster

18 May 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Four Movie Stars, Locust Valley Cemetery

31 March 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Silhouette version of RJ portrait by Joan Harrison, Lattingtown Beach

Autumn 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

To create this picture-within-a-picture, Johnson returned to the site of a much-reproduced portrait of him that photographer Joan Harrison made in the early 1980s. In the spot where he once sat, knees raised and arms outstretched, Johnson leaned a card that features a black silhouette of his symmetrical pose. As so often occurs in his photographs, Johnson here strikes an unsettling balance between absence and presence, erasure and memorialisation.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Bill and Railroad Tracks)

Spring 1992)

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Bill and Long Island Sound

Winter 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Johnson held up the sky-blue bill of a baseball cap over a railroad crossing and photographed it. When he holds it over the ocean in another image, it resembles a crescent moon. With his “throwaway” camera he photographed arrangements of photographs and photobooks by Walker Evans, Lord Snowden, Richard Avedon, Bill Brandt, and Lee Friedlander. Friedlander-like, Johnson photographed his own shadow, interacting with the places of his solitary visits.

He photographed his own works in infinite arrangements and continuous correspondence: two bunnyheads sitting up conversationally in tall chairs. He photographed his headshot, affixed to the passenger seat of a car, next to a double photo of Elvis, in the driver’s seat. He photographed a blank billboard in a field; he photographed a pier; he photographed the ocean. He photographed a picture of himself in his shadow cast across a mailbox, a bunny head peeking out. The unearthed photographs become the last note sent.

Rrebecca Bengal. “Photo Dump: Digging into the 5,000 Photographs Ray Johnson Left Behind,” on the Elephant Art website 20 Jul 2022 [Online] Cited 25/09/2022

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

RJ reflected in ice truck and split Duane Michals Movie Star

11 May 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Back steps and moticos

Spring 1992

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Twins

In his writing and visual art, Johnson used juxtapositions and puns to suggest that nothing stands alone: everything finds correspondence in something else. Photography’s optical literalness gave him new ways to explore reality’s doubleness. Twins – and photocopied photographs – are nearly alike yet insistently distinct. Mirrors give back a faithful, yet laterally reversed, image of nature. The shadow of a thing echoes its original, but (like a moticos) it is flat and empty of internal detail.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Bunny drawn on Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled”

2 January 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Long Dong Silver, Lattingtown Beach

16 November 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Six Movie Stars in RJ’s car

April 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bunnies

A round-eyed, long-nosed bunny head functioned as Johnson’s signature and, as he said, “a kind of self-portrait.” Despite the bunny’s blank expression, context can render it comical, hapless, sinister, or obscene. Johnson altered Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s photograph of a rumpled empty bed – an iconic image of gay mourning during the AIDS crisis – by resting a lone bunny’s head on one of the two pillows. Johnson cut a face-sized hole out of one bunny, then photographed the view outside his front window through the gap. He gave the same bunny to passersby to wear and, once, laid it suggestively atop his toilet bowl. When a large old tree next door was being chainsawed apart, Johnson found in its branching form a gaunt, eyeless bunny’s face.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Harpo Marx bunny, headshot, and payphone

February 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Bunny tree in backyard

17 April 1993

Commercially processed chromogenic print

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (red bunny NOTHING)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

12 1/2 × 7 1/2 in. (31.75 × 19.05cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

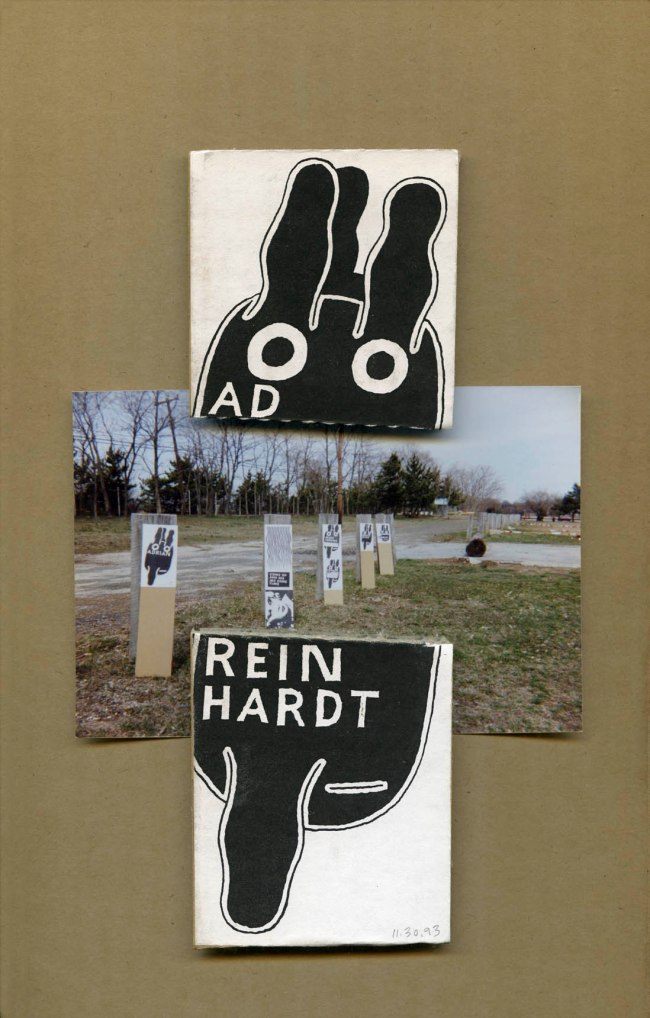

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Untitled (Ad Rein Hardt Bunny)

1993

Collage on corrugated cardboard

12 1/2 × 7 5/8 in. (31.75 × 19.37cm)

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Flopped stranger wearing cutout bunny

Spring 1992

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

What did Johnson intend to do with the thousands of photographs he made between 1992 and 1994? There are few solid indications. He mailed some to correspondents, either in the form of original prints or as photocopies. He also incorporated a handful of his photographs into collages that differ markedly in scale and sensibility from the larger, contemporaneous Movie Stars. In one collage, a photograph of five Movie Stars – arranged like sequential ads beside a road – is punningly combined with a bunny head bearing the name of abstract painter Ad Reinhardt (1913-1967), a friend and employer of Johnson’s in his early New York years.

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

Shadow of RJ’s mailbox

March 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Ray Johnson (American, 1927-1995)

RJ with PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE and camera in mirror

23 December 1994

Commercially processed chromogenic print

4 × 6 in.

The Morgan Library & Museum

Gift of the Ray Johnson Estate, courtesy of Frances Beatty

© Ray Johnson / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

This self-portrait appears on a roll of film Johnson turned in for developing about three weeks before his suicide by drowning on 13 January 1995. The flopped lettering on the Movie Star in his hand undergoes a further reversal in the mirror. On a literal level, the words “REAL LIFE” refer to the New York-based art magazine REALLIFE (1979-1994), which Johnson hoped would soon publish an article about his years-long collaboration with a friend, Sheila Sporer. But the message unmistakably announces, too, that the artist was soon to venture beyond the reach of “real life.”

The Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Avenue at 36th Street, New York, NY

Phone: (212) 685-0008

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Thursday, Saturday – Sunday: 10.30am – 5pm

Friday: 10.30am – 7pm

Closed Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.