Exhibition dates: 5th October 2018 – 10th February 2019

Curated by Steven Matijcio

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Damaged Negatives: Scratched Portraits of Mrs. Baqari

2012

Made from 35mm scratched negative from the Hashem el Madani archive

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

“As a holistic specimen without fixed parameters, “An informed object,” Zaatari elaborates, “is an object that is conscious of the material and processes that produced it, conscious of its provenance, its morphology and displacement over time, conscious of its history in the sense that it is able to communicate it. An informed object is already materialised, activated.” His self-declared “displacement” of these objects is thusly not about post-colonial uprooting, but rather a deeper, wider recognition of the apparatus that informs the production, circulation and reception of such images in, and beyond their respective context/s. In this expanded field, negatives, contact sheets, glass plates, double exposures, mistakes, erosion and all that is habitually left on the cutting room floor are re-valued as revelatory anomalies with “something to say”.”

Akram Zaatari quoted in Steven Matijcio / 2018

Alternate readings / elisions / a damaged life

This is the first posting of 2019, a new year, a new year of history, memory and life. And what a cracker of an exhibition to post first up!

I have always admired the Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari for the ability of his work to critique the inevitable, referential history of photographs. Anyone who can shine a light on forgotten narratives, histories, contexts and memories, who enlightens the fixed gaze of the camera and the viewer to show the Other, and who empowers the disenfranchised and tells their stories… is excellent in my eyes. For this is what Art Blart has sought to do in the last ten years: build an archive that exposes underrepresented artists and forgotten histories to the world.

Photography, and life, is not all that it seems… and Zaatari implicitly understands the conundrums of the taking, viewing and collecting of photographs in archives. He understands the physical quality of the medium (the presence of the negative, the glass slide, the print and their manipulation by the photographer) as well as the truth of the medium, a kind of truth telling – through history, time, the personal and the collective – that obscures as much as it reveals. As his short biography notes, “Akram Zaatari is an artist whose work is tied to collecting and exploring photographic practices in the making of social codes and aesthetic forms. Regarding the present through a wealth of photographic records from the past… Zaatari investigates notions of desire, pursuit, resistance, memory, surveillance, the shifting nature of political borders and the production and circulation of images in times of war.” Indeed, a rich investigative field which Zaatari makes full use of in his work.

Simply put, the project that Zaatari is undertaking is one of archaeological excavation / re-animation of the many aspects of the cultural geography of Lebanon, his role as auteur in this process combining “image-maker, archivist, curator, filmmaker and critical theorist to examine the photographic record, its making, genealogy and the role photography plays in the production and performance of identity.” (Wall text) “I’m really interested in how the personal and the intimate meet history,” Zaatari says. “What I’m doing is to write history, or [fill in] gaps of history, by using photographic documents.”1

Zaatari “deconstructs the archival impunity of photography to cultivate an expanded architecture of interpretation,” (Wall text) exploring the fold as a catalyst, a narrative, a re-organisation, an enduring obfuscation, and the memory of a material. What a photograph missed and what is present; what an archive catalogues and how, and what it misses, elides or denigrates (the classification system of an archive). As Rebecca Close observes, “The question of what an archive of the image fails to commemorate is particularly relevant in a country marred by decades of civil war and invasion.”2

It is also particularly relevant in a country (and a world) where men are in control. Zaatari interrogates (if I may use that pertinent word) the partitioning of history (between Palestine and Israel), the poses of decorum between male and female, the power of men in marriage, the stigma of homosexuality, male normativity, and “Zaatari’s framing of these photos (particularly as diminutive contact sheets) suggests modern cracks in the visual codification of patriarchal rule…” (Steven Matijcio) The centre cannot hold the weight of these hidden his/stories, as invisible “non-collections” (E. Edwards) in institutions are opened up for critical examination. The damage that accrues through such obfuscation, through such wilful blindness to the stories embedded in photographs is boundless.

What we must remember is that, “photography always lies for the photograph only depicts one version of reality, one version of a truth depending on what the camera is pointed at, what it excludes, who is pointing the camera and for what reasons, the context of the event or person being photographed (which is fluid from moment to moment) and the place and reason for displaying the photograph. In other words all photographs are, by the very nature, transgressive because they have only one visual perspective, only one line of sight – they exclude as much as they document and this exclusion can be seen as a volition (a choice of the photographer) and a violation of a visual ordering of the world (in the sense of the taxonomy of the subject, an upsetting of the normal order or hierarchy of the subject). Of course this line of sight may be interpreted in many ways and photography problematises the notion of a definitive reading of the image due to different contexts and the “possibilities of dislocation in time and space.” As Brian Wallis has observed, “The notion of an autonomous image is a fiction” as the photograph can be displaced from its original context and assimilated into other contexts where they can be exploited to various ends. In a sense this is also a form of autonomy because a photograph can be assimilated into an infinite number of contexts. “This de and re-contextualisation is itself transgressive of any “integrity” the photograph itself may have as a contextualised artefact.” As John Schwartz has insightfully noted, “[Photographs] carry important social consequences and that the facts they transmit in visual form must be understood in social space and real time,” “facts” that are constructions of reality that are interpreted differently by each viewer in each context of viewing.”3

I have no problem with the ethics and politics of the use of photo archives by contemporary artists and the appropriation of archival images as a form of “ironic archivization” to open up new critical insights into culture, and the culture of making, reading and archiving photographs. Zaatari appropriates these images for his own concerns to shine a light on what I call “the space between.” His interdisciplinary practice mines the history of the image while simultaneously expanding its legacy and life. As he observes of his profound and sensitive work, “Every photograph hides parts to reveal others… What a photograph missed and what was present at the time of exposure will remain inaccessible. In those folds lies a history, many histories.” With this powerhouse of an artist, these histories will not remain hidden for long.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Venema, Vibeke . “Zaatari and Madani: Guns, flared trousers and same-sex kisses,” on the BBC News Magazine website 17 February 2014 [Online] Cited 07/12/2108

2/ Close, Rebecca. “Akram Zaatari,” in ArtAsiaPacific No. 104, Jul/Aug 2017, p. 108. ISSN: 1039-3625 [Online] Cited 07/12/2108. No longer available online

3/ Bunyan, Marcus. “Transgressive Topographies, Subversive Photographies, Cultural Policies,” on Art Blart, October 2013 [Online] Cited 07/12/2108

Many thankx to Akram Zaatari and the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Acclaimed Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari combines the roles of image-maker, archivist, curator, filmmaker and critical theorist to explore the role photography plays in both instituting and fabricating identity. He is also co-founder of the Arab Image Foundation (AIF), an organisation established in Beirut to preserve, study and exhibit photographs from the Middle East, North Africa and the Arab diaspora from the 19th century to today. Within this endeavour Zaatari discovered the photographs of Hashem El Madani (1928-2017), who recorded the lives of everyday individuals inside and outside his humble studio in the late 1940s and 50s. Zaatari recontextualises this work, along with other archival photos and documents, in an interdisciplinary practice that mines the history of the image while simultaneously expanding its legacy and life. His work is both for and against photography, and the complex histories it cobbles.

For this exhibition he positions the seemingly simple fold as a narrative form, a reorganisation, an enduring obfuscation and the memory of material. In his words, “a photograph captures space and folds it into a flat image, turning parts of a scene against others, covering them entirely. Every photograph hides parts to reveal others… What a photograph missed and what was present at the time of exposure will remain inaccessible. In those folds lies a history, many histories.” The work on display will attempt to uncover and imagine these stories, undertaking a provocative archaeology that peers into the fissures, scratches, erosion and that which archives previously shed.

Presented in partnership with FotoFocus Biennial 2018. Text from the Contemporary Arts Center website

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Damaged Negatives: Scratched Portrait of an anonymous woman

2012

Made from 35mm scratched negative from the Hashem el Madani archive

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Damaged Negatives: Scratched Portraits of Mrs. Baqari and her friend

2012

Made from 35mm scratched negatives from the Hashem el Madani archive

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Hands at Rest (video stills)

2017

SD Video / Running time: 7:30

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

This film is a meditative study of a selection of studio photographs culled from Lebanese photographer Hashem el Madani’s archives. In response to Madani’s maxim that “posing one’s hands on a flat surface such as a table, or a shoulder helps to straighten one’s shoulders,” Zaatari looks closely from one hand to the next, creating a portrait of Lebanese society that implicitly questions the politics embedded in poses of propriety and decorum. Fingers fitted with rings and bodies displaying the comfort and composure of a certain class are juxtaposed with others indicative of manual labor and untrained modelling. The slow, but precise inventory of the video, devoted to the most tactile limb in one’s body, also elicits the ever-present sensuality which circulates throughout Madani’s photographs.

Wall text from the exhibition

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Najm (left) and Asmar (right) 1950-1959, Lebanon, Saida. Hashem el Madani

From Akram Zaatari’s Objects of Study/The archive of Studio Shehrazade/Hashem el Madani/Studio Practices

2014

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

© A. Zaatari/Arab Image Foundation

Photo: Tony Walsh

Zaatari says that was normal in the 1950s. “If you had your picture taken you would seize the opportunity to create something different of yourself,” he says. “They wanted to look at themselves as if they were looking at an actor in a film.” It was fun.

Movies were a great source of inspiration for Madani’s sitters. This included acting out a kiss – but only men kissing men and women kissing women. “In a conservative society such as Saida, people were willing to play the kiss between two people of the same sex, but very rarely between a man and a woman,” Madani told Zaatari. He remembers that happening only once.

“If you look at it today you think – is it gay culture? But in fact it is not,” says Zaatari. Social restrictions were different then. “If you wanted to kiss it had to be a same-sex kiss to be accepted.”

Men showed off their photos, but for women a picture was considered intimate and would only be shared with a trusted few. Madani had purposely found a studio space on the first floor, so that women could visit discreetly – seen entering at street level, their destination would not be obvious. Once inside, they could relax – but it did not always end well.

Extract from Vibeke Venema. “Zaatari and Madani: Guns, flared trousers and same-sex kisses,” on the BBC News Magazine website 17 February 2014 [Online] Cited 07/12/2108

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Najm (left) and Asmar (right) 1950-1959, Lebanon, Saida. Hashem el Madani

From Akram Zaatari’s Objects of Study/The archive of Studio Shehrazade/Hashem el Madani/Studio Practices

2014

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

© A. Zaatari/Arab Image Foundation

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Bodybuilders Printed From A Damaged Negative

2011

C-print

145 x 220cm

Ed 5 + 2AP

© Akram Zaatari

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Bodybuilders, Printed From A Damaged Negative Showing From Left To Right: Hassan El Aakkad, Munir El Dada And Mahmoud El Dimassy In Saida, 1948

2011

C-print

145 x 220cm

Ed 5 + 2AP

© Akram Zaatari

American Psychological Association links ‘masculinity ideology’ to homophobia, misogyny

For the first time in its 127-year history, the American Psychological Association has issued guidelines to help psychologists specifically address the issues of men and boys – and the 36-page document features a warning.

“Traditional masculinity ideology has been shown to limit males’ psychological development, constrain their behaviour, result in gender role strain and gender role conflict and negatively influence mental health and physical health,” the report warns.

The new “Guidelines for the Psychological Practice with Boys and Men” (August 2018) defines “masculinity ideology” as “a particular constellation of standards that have held sway over large segments of the population, including: anti-femininity, achievement, eschewal of the appearance of weakness, and adventure, risk, and violence.” The report also links this ideology to homophobia, bullying and sexual harassment.

The new guidelines, highlighted in this month’s issue of Monitor on Psychology, which is published by the APA, linked this ideology to a series of stark statistics: Men commit approximately 90 percent of all homicides in the U.S., they are far more likely than women to be arrested and charged with intimate partner violence in the U.S., and they are four times more likely than women to die of suicide worldwide. …

The report addresses the “power” and “privilege” that males have when compared to their female counterparts, but it notes that this privilege can be a psychological double-edged sword.

“Men who benefit from their social power are also confined by system-level policies and practices as well as individual-level psychological resources necessary to maintain male privilege,” the guidelines state. “Thus, male privilege often comes with a cost in the form of adherence to sexist ideologies designed to maintain male power that also restrict men’s ability to function adaptively.”

Extract from Tim Fitzsimons. “American Psychological Association links ‘masculinity ideology’ to homophobia, misogyny,” on the NBC News website [Online] Cited 10/01/2019

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Bodybuilders, Printed From A Damaged Negative Showing Hassan El Aakkad In Saida, 1948

2007

C-print

220 x 145cm

Ed 5 + 2AP

© Akram Zaatari

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Bodybuilders Printed From A Damaged Negative

2011

C-print

Ed 5 + 2AP

220 x 145cm

© Akram Zaatari

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Bodybuilders Printed From A Damaged Negative

2011

C-print

220 x 145cm

Ed 5 + 2AP

© Akram Zaatari

The Fold

The fold is the pleat that results from turning or bending part of material against another such as in textile, paper or even earth strata. The fold is the trace that such an action leaves on material, the crease that marks the location of turning and pressing.

Inherent in the action of folding, is that material is turned or moved in three dimensions hence engages with space. Folding is the basic and simplest step in creating form or enclosure. It confines space within folds. It covers parts with other parts. Folding is editing. It is a construction that does not look like its original form.

Unfolding is undoing, deconstructing, turning material back to its initial form. The creases in an unfolded material inscribe its history and in a way save it from amnesia. History inscribes itself on material in creases and in other forms. When unfolded, material testifies that history has already found its way to it, through the fold.

The fold is the memory of material.

When the fold is intentional, it aims to reorganise material to reduce its volume, to create form, or confine space. When accidental or natural such as in geology, or due to ageing organic matter, the fold is a permanent deformation of matter the form of which remains little predictable.

When intentional, the fold is a creative action, like folding a paper sheet into a paper airplane or an origami, like folding several sheets into a book, or a sheet of cardboard into a box or even folding clothes to reduce their volume and store them on a shelf or in a box of specific dimensions.

The fold is a narrative form.

In a way every photograph is an exposure of a field of vision, of something somewhere. Like folding confines space, a photograph captures space and folds into a flat image, turning parts of a scene against others covering them entirely. Every photograph hides parts to reveal others. Every photograph reproduces in small what’s much larger in life, or brings close an image of somewhere far and out of sight. The impact of a fold in a photographed space is permanent, in the sense that hidden parts in a picture are irretrievable. What a photograph missed and that was present at the time of exposure will remain inaccessible. In those folds lies a history, many histories.

The fold in a photograph is a detail through which a narrative different from that narrated by the photograph unfolds. It is an element through which the initial construction of a photograph, its making, is undone. It is an element that bears the history of a photograph, its memory.

The fold in time is the representation of time shortened, like in literature, in illustration or typically in film. The fold in time is the ellipsis. The fold within a narrative is the jump-cut or the jump in time. The fold acknowledges the existence of hidden narratives covered by others. In a film, the cut is the fold.

Akram Zaatari

General installation views

Installation views, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Left

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

[Unlabelled]

Cairo, Egypt 1940s

Inkjet print of gelatin silver negative on cellulose acetate film

Photographer: Alban

Courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation

A negative for photography is equivalent to an engraved zinc plate for traditional print-making. Not only does it allow for the reproduction of the image or print but it itself carrier traces of the tricks the photographer has used while making a picture. As such, photographers did not want their negatives to be displayed because they often carried details the studio might not want to share with the public. The portrait of a baby was made by the Cairo based photographer Alban in the 1940s. Access to the negative tells us that the baby was held by his mother and that she was later withdrawn from the picture

Wall text from the exhibition

Right

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

[Unlabelled]

Tripoli, Lebanon 1980s

Inkjet print of gelatin silver negative on cellulose acetate film

Photographer: Joseph Avedissian

Collection: Joseph Avedissian

Courtesy of the Arab Image Foundation

At at time when going to a photography studio was the only way for people to be photographed for ID or other official purposes, these spaces were shared by a wide spectrum of society. During the Lebanese civil war, they were sometimes employed by opposing militias and certainly by civilians as well. Joseph Avedissian set up his first studio in the late 1950s in al Tell in Tripoli, North Lebanon. Like most inner cities during the civil war in Lebanon, al Tell was the playground of numerous militias ranging from the different Palestinian factions and the Syrian army extending to the Al Tawheed Islamic group in the 1980s. Zaatari visited Avedissian’s with the photographer Randa Saath in 2002. Thousands of negative sheets covered the floor, from where he picked up this sheet that represents one member of the local militia posing with his machine gun. Because of poor preservation, however, a patch of emulsion coming from another exposed negative was accidentally bound to it depicting a woman. The result is an uneasy co-habitation in the shared frame.

Wall text from the exhibition

The End of Love

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

The End of Love (installation view)

2013

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

The End of Love (installation view)

2013

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

The End of Love (installation view detail)

2013

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

The End of Love (installation view detail)

2013

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

The End of Love (installation view detail)

2013

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Every photograph hides parts to reveal others…

Akram Zaatari

Desire for the archive as an unassailable repository of documents, testimony and truth seems to escalate despite, or perhaps because of, the more imminent reality that there is no singular history on which all peoples can agree. And while the “post-truth” era feels pandemic in North America, in other parts of the world this is an all too familiar paradigm where the manipulation of the past is a customary practice to administer the present, and influence the future. This is especially true of Lebanon, where fifteen years of malignant civil war from 1975-1990 has produced a knotty, contested history riddled with sectarian animosities, institutionalised amnesia, and ubiquitous uncertainty. And yet when nothing is solid, codified or certain, everything becomes possible. Across the Middle East where formal archives remain partial and at risk, an increasing number of artists employ the fragments as fodder for new forms of historical preservation and production. Akram Zaatari (b. 1966 Sidon, Lebanon) is a pioneer within this amorphous terrain, marrying personal experiences of the war, an abiding interest in the vernacular performance of identity via photo and film and a quasi-archaeological treatment of lens-based documents as artefacts. Beyond his individual practice, one of Zaatari’s greatest, most enduring contributions in this field may be the Arab Image Foundation (AIF) – an archival institution he co-founded with photographers Fouad Elkoury and Samer Mahdad in 1997 to self-declaredly “preserve, study and exhibit photographs from the Middle East, North Africa and the Arab diaspora from the 19th century to today.” And while the AIF has successfully amassed over 600,000 images from multiple countries and eras, Zaatari adamantly refutes the onset of institutionalisation – shunning the paralysing conservation practices of museums and libraries to double down on a more radical, generative employment of these materials. In his hands, this archive moves beyond a delicate commodity to circulate as a mutable constellation that partakes in an expanded field of histories with cumulative socio-cultural cargo. As such, the archive can be seen as both Zaatari’s medium and subject, and the AIF as both his fuel and foil – collecting and re-presenting photos as “a form,” in his words, “of creative un-making and re-writing that is no less important than the act of taking images.” Ensuing questions of authorship and appropriation yield to more multi-faceted strategies of displacement, where the re-framing of photos and films as living, changing vessels unfurls invigorating new layers and folds to mine and forage.

He does so, not as an iconoclast seeking to condemn archives as cogs in the machine of hegemony, but rather as a revitalising gesture that replaces rhetorical manipulations with emancipated re-assignment. For Zaatari, this frisson happens most intriguingly in the seemingly ordinary and banal, in the snapshots and mistakes archives historically diminish, where he argues, “It is a misconception that photographs testify to the course of history. It is history that inhabits photographs.” As such, Zaatari regularly subverts the canonical treatment of photos as evidentiary relics hidden away in cold storage to slow their inherent / inevitable chemical entropy. He instead treats images as susceptible material objects, and one could argue, as surrogates for the subjects and structures they depict. Much like the wrinkles, scars and repressions that the human body + mind collects, Zaatari reads the folds endemic to photography as a palimpsest of information and suggestion. Whether it be a purposeful edit or crop, an aesthetic gesture to redirect our viewing, or the natural degradation of materials over time, he argues that “The fold in a photograph is a detail through which a narrative different from that narrated by the photograph unfolds.” As fertile superstructures that expand the interpretive constitution of said photos, such folds are less obfuscations than nascent fonts for alternative narratives to percolate. “In these folds lies a history…” according to Zaatari, “many histories.” In this inclusive arena, the micro and macro flow into one another as citizen and state intermingle, and one discovers pockets of collective history in the pictures we have of ourselves and one another. These photos and their attendant folds do not float unattached in clouds, but instead coalesce as archives of their making, and lenses to look backward and forward.

In his position that “the traces that transactions leave on a photographic object become part of it,” Zaatari argues that the physical manufacture and decay of a photograph (or film) is as much a contribution to history as that which it depicts. He calls the ensuing composites “informed objects,” which, while partial or possibly broken, highlight the greater whole “like an exploded view of a machine,” or “a model of the human body used in anatomy class.” As a holistic specimen without fixed parameters, “An informed object,” Zaatari elaborates, “is an object that is conscious of the material and processes that produced it, conscious of its provenance, its morphology and displacement over time, conscious of its history in the sense that it is able to communicate it. An informed object is already materialised, activated.” His self-declared “displacement” of these objects is thusly not about post-colonial uprooting, but rather a deeper, wider recognition of the apparatus that informs the production, circulation and reception of such images in, and beyond their respective context/s. In this expanded field, negatives, contact sheets, glass plates, double exposures, mistakes, erosion and all that is habitually left on the cutting room floor are re-valued as revelatory anomalies with “something to say.” Zaatari’s poignant 2017 series A Photographer’s Shadow is a case in point, presenting a number of historical photos where the cameraman’s shadow has infiltrated the composition, which was historically reason to throw the picture away. In Zaatari’s revised appraisal, however, such discards are instead accentuated as elucidating nexus points where author and subject meet within the frame. A diptych of found photos Zaatari premieres in the CAC exhibition thickens this premise even further, displaying a malfunction in the camera of Hashem el Madani (1928-2017) that led to an in-frame doubling of men (presumably father and son) standing upon the rocks of a swelling shoreline. Evoking past hallmarks of romantic painting, a multiplicity gathers with equal muster across this pairing as the images coagulate with the residue and implication of generational, production and art historical lineage. The cresting physicality of this informed object is pushed even further in the 2017 work Against Photography, which removes the image from the equation to instead detail the natural patterns of environmental decay upon a series of 12 photo plates. By extracting the traditional focal point of the photographic process, Zaatari instead surveys iterations of deterioration that take on an uncanny beauty in multiple media – turning the archival chimera of folds and fracture into a verdant topography of patterns, avenues, and stories untold.

The continued consideration of the photograph as a physical entity with corresponding history, memory and lifespan connects to Zaatari’s ongoing exploration of the human body as it is performed for, and by the camera. As an index of experience and identity, the body and its photographic proxy find a surrogate-like relationship in the images he provocatively re-frames – where intimate narratives are gleaned from voluminous collections and otherwise numbing aggregates. And while we are only sometimes privy to the background and/or the names of those photographed, Zaatari is a long-standing student of the ways in which gender, sexuality and taboo are concurrently codified and obscured by indigenous photographic practices. By re-contextualising private photos in a public arena, Zaatari “frequently composes works,” according to Professor Mark Westmoreland, “that force the photographic medium to comment upon social aesthetics that it has been deployed to produce at different historical moments.” A compelling example is found in Zaatari’s 2011 re-presentation of Madani’s timeworn photographs of male bodybuilders performing feats of both physical strength and acrobatic agility in a showcase of masculine prowess. Inferences to homo-eroticism within this display were comparatively forbidden; and, while we must resist the temptation to define historical images through the lens of today, the entropic folds highlighted in Zaatari’s framing of these photos (particularly as diminutive contact sheets) suggests modern cracks in the visual codification of patriarchal rule, male normativity, and the stigma of homosexuality. Like the photographer’s shadow that interrupts the self-contained world of his subjects in Zaatari’s aforementioned work, the humbling eclipse that befalls many an ideology and monument creep over a pantheon of bravado here. The violent exercise of patriarchal custody is on frightening display in Zaatari’s 2012 diptych Damaged Negatives: Scratched Portraits of Mrs. Baqari and her friend, where otherwise benign photographs of two young women are marred by a flurry of black scratches. These disturbing scars are the product of a controlling husband who demanded Madani lacerate the negatives of a portrait session initiated by his wife before they were married. Years later, after Mrs. Baqari burned herself to death to escape his control, the widowed husband came back to Madani’s studio asking for enlargements of these photos. Their display decades later under the auspices of this exhibition demonstrates the extraordinary valence of the fold, which in this case manifests a tragic relationship, evokes the history of effigies and iconoclasm, embodies the systematic societal violence against women, and opens up a plethora of readings that could not exist without slashes that span both object and subject.

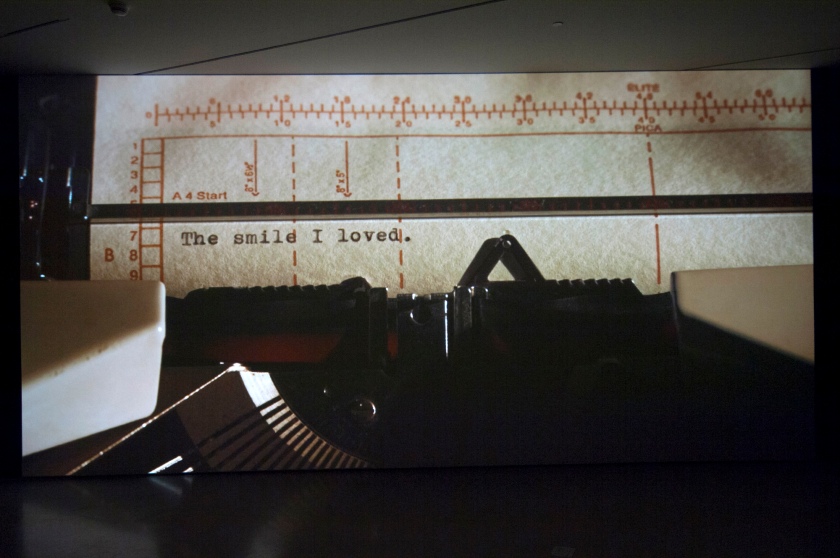

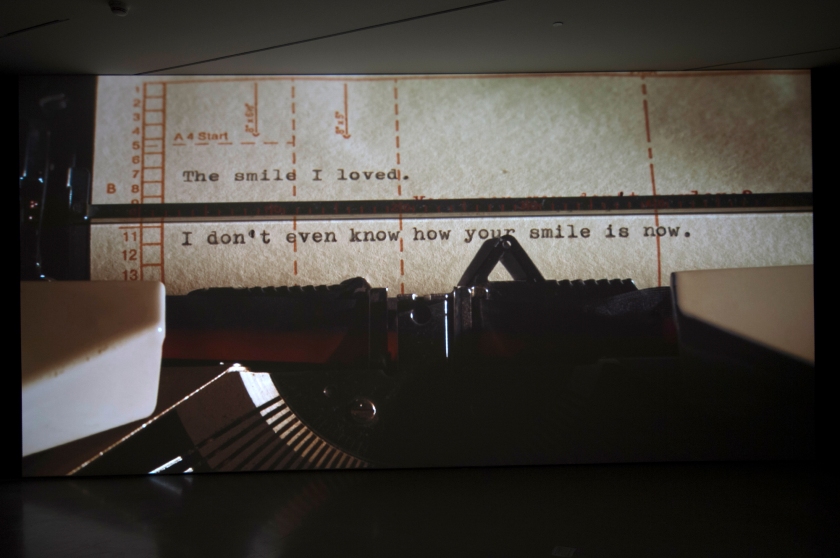

The social life of the informed objects that Zaatari presents thereby opens a larger sociological discourse which, in the case of Lebanon, speaks to the ways love and sexuality have been regulated – and liberated – via photography and film. He traces the visual trajectory of this contested history largely by way of Madani’s studio photography, which pictured thousands of people over the course of almost half a century in Zaatari’s hometown of Saida. The ensuing photos demonstrate a complex spectrum of desire as people moved across both sides of the state-sanctioned line, performing the love they coveted and that which they concealed. As a site of concurrent fantasy and societal uniformity, what genders, professions, events and relationships were prescribed to “look like” created an orthodoxy of both restrictions and their corresponding transgressions. In The End of Love (2013), Zaatari presents over 100 photos of wedding portraits taken in Madani’s studio that collectively illustrate the codes surrounding this classic trope. Kissing was forbidden for such a photo which, in Lebanon, was taken a week after the ceremony with the bride wearing her wedding dress, supplemented by a bouquet of plastic flowers and white gloves provided by the photographer. And while the ensuing images are stiff, sober and highly formulaic, this End of Love is not a cynical farewell to the romantic aura of marriage, but rather a site where ideals collect in the margins, in aspirations that exceed both the subject and frame. Much like Arthur Danto’s post-historical 1984 essay “The End of Art,” Zaatari’s collection implies the exhaustion of a particular lineage of love and the opening of a chaotic, open-ended eddy where de-regulated desire could be performed. Madani’s studio was the site and catalyst for many of these performances; but, in this exhibition Zaatari pairs The End of Love with the aspiration of his 2010 video Tomorrow Everything will be Alright, in which a proposed reunion of estranged lovers is told in the form of typewritten dialogue. The voices here remain anonymous throughout, much like the many couples in The End of Love, and we gradually learn that these contemporary, same-sex lovers speak in prose drawn from popular cinematic clichés. Their conflicted flirtation culminates in the familiar romantic trope of a sunset at seashore, and more specifically that portrayed in the 1986 film Le Rayon Vert in which a disillusioned woman’s faith in love is restored after she sees a green flash at twilight. And yet, despite the overt homage, the time stamp in the bottom corner of Zaatari’s version implies this is his personal footage. And, that amidst many formulae, clichés and the already said, in the seams between The End of Love and Tomorrow Everything will be Alright, something unique and human can be spoken.

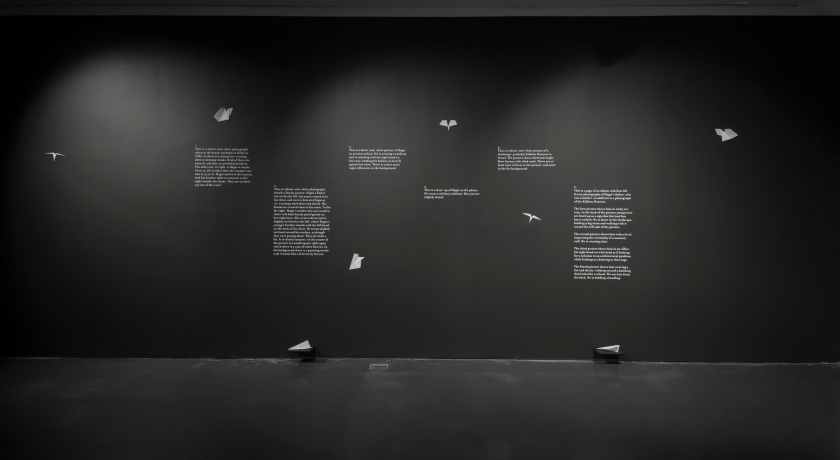

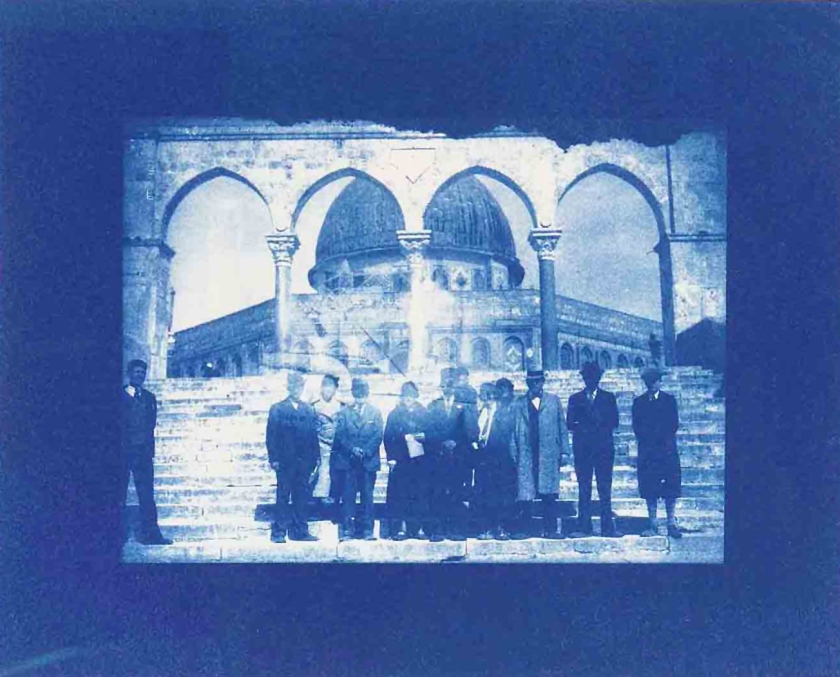

In contrast to the charge that photos are moments plucked out of time – slowly staving off death in the airless preservation of archives – Zaatari re-situates photos entrusted to the AIF in a multiplied field that spans origins and invention. Rather than entrenching images with fixed historical assignments, he performs subtle interventions to uncover and suggest alternate readings that inject life into said objects. As a stirring case in point, Un-Dividing History (2017) merges historical images by Khalil Raad (1854-1957), a Palestinian from Jerusalem, and Yacov Ben Dov (1882-1968), a Zionist-Ukrainian filmmaker and photographer, who dually inhabited Jerusalem from 1907-1948 but “belonged,” in Zaatari’s words, “to completely different universes.” Glass photo plates from each of these men had been acquired into a private collection years later and stored against each other for over a half-century in the same position, slowly and mutually “contaminating” one another with the opposing image. Zaatari’s cyanotypes reveal these beautifully compromised hybrids, depicting “traces of one world inscribed into another,” and symbolically de-partitioning the tragic schisms / folds that have long scarred this population and place. This grid of 8 images is not one of easy, idealistic harmony, but rather a complex, messy, fundamentally human portrait of the way lives intersect and overlap, if only they are allowed. A related moment of extraordinary, stirring empathy is found in the 2013 project Letter to a Refusing Pilot, in which Zaatari realises the rumour of Hagai Tamir, an Israeli fighter pilot, who in 1982, during his country’s invasion of Lebanon, disobeyed the order to drop a bomb on what he knew to be a schoolhouse. The legend, and Zaatari’s ensuing interview with Tamir have taken multiple forms in the translation to art, most notably paper planes that have appeared in both video and physical form, floating across terrain that spans real and virtual, truth and myth. What in theory started as a description, or a document, or a letter, has thereby taken flight via multiple folds – transforming this story into a mutable vessel that lands often, but temporarily – its ultimate destination indeterminate. In this lightness of being and itinerant course, the paper plane embodies Zaatari’s affinity for ephemeral records rather than the weighted gravity of archives. These are images, objects, videos, memories and outtakes that bear creases, evince life, and find renewal in each and every reappraisal.

Steven Matijcio / 2018

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Tomorrow Everything will be Alright

2010

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Tomorrow Everything will be Alright (video still)

2010

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Tomorrow Everything will be Alright (video still)

2010

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Tomorrow everything will be alright

2010

Akram Zaatari was born in 1966, in Sidon, Lebanon and currently lives in Beirut. Zaatari works in photography, video, and performance to explore issues pertinent to the Lebanese postwar condition, specifically the mediation of territorial conflicts and wars though television and media. Zaatari collects and examines a wide range of documents that testify to the cultural and political conditions of Lebanon’s postwar society. His artistic practice involves the study and investigation of the way these documents straddle, conflate, or confuse notions of history and memory. By analysing and recontextualising found audiotapes, video footage, photographs, journals, personal collections, interviews, and recollections, Zaatari explores the dynamics that govern the state of image-making in situations of war. The strength of Zaatari’s work lies in its ability to capture fractured moments in time, even if these sometimes confuse because of their disconnect from the audience and lack of context. Regardless, the stories hold their own as fascinating narratives, managing to reflect on such universal themes as love and lust, and sweet reminiscence, even amidst turbulent political realities. The indie film was nominated for the teddy award for best short film in 2011.

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Letter to a Refusing Pilot 1

2013

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Letter to a Refusing Pilot 2

2013

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Letter to a Refusing Pilot 3

2013

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Letter to a Refusing Pilot4

2013

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Letter to a Refusing Pilot 5

2013

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Letter to a Refusing Pilot (installation view)

2013

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

In the summer of 1982, a rumour made the rounds of a small city in South Lebanon, which was under Israeli occupation at the time. It was said that a fighter pilot in the Israeli air force had been ordered to bomb a target on the outskirts of Saida, but knowing the building was a school, he refused to destroy it. Instead of carrying out his commanders’ orders, the pilot veered off course and dropped his bombs in the sea. It was said that he knew the school because he had been a student there, because his family had lived in the city for generations, because he was born into Saida’s Jewish community before it disappeared. As a boy, Akram Zaatari grew up hearing ever more elaborate versions of this story, as his father had been the director of the school for twenty years. Decades later, Zaatari discovered it wasn’t a rumour. The pilot was real. Pulling together all of the different strands of Zaatari’s practice for the first time in a single work, Letter to a Refusing Pilot reflects on the complexities, ambiguities, and consequences of refusal as a decisive and generative act. Taking as its title a nod to Albert Camus’ four-part epistolary essay “Letters to a German Friend,” the work not only extends Zaatari’s interest in excavated narratives and the circulation of images in times of war, it also raises crucial questions about national representation and perpetual crisis by reviving Camus’s plea: “I should like to be able to love my country and still love justice.”

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Against Photography (installation view)

2017

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

In an October 2012 interview with anthropologist Mark Westmoreland, Zaatari further probed whether emotions can be preserved with pictures. The difficulty in resolving the matter perhaps motivated the artist’s move into increasingly abstract terrain. The exhibition’s titular work confirms Zaatari’s current reticent position. Against Photography (2017) – 12 aluminium engravings produced from weathered negatives scanned and then put through a 3D scanner that records only surface texture – withdraws from the image entirely, leaving behind only the shine of relief.

Close, Rebecca. “Akram Zaatari” in ArtAsiaPacific, No. 104, Jul/Aug 2017, p. 108. ISSN: 1039-3625. Cited 07 Dec 18. No longer available online

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Against Photography (installation view detail)

2017

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Against Photography (installation view, right)

2017

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Against Photography (installation view detail)

2017

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Against Photography (installation view detail)

2017

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image with at left, Un-Dividing History 2017

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Un-Dividing History (installation view)

2017

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

These cyanotypes merge two bodies of work from a collection which is no longer in the Arab Image Foundation’s custody, and which consisted of glass plates of Khalil Raad, a photographer from Jerusalem, and those of Yacov Ben Dov, a Zionist filmmaker and photographer of Ukrainian descent. Raad and Ben Dov shared the same city, Jerusalem, but belonged to completely different universes. Zaatari conceived this series as a statement against partitioning history. As the glass plates were stored against each other for over 50 years in the same position, each plate was contaminated by the plate it was leaning against. The cyanotypes depict traces of a world impressed onto another and speak of the ineluctable shared history of Palestine and Israel, safeguarded by a passionate collector.

Anonymous text from the Sfeir-Semler Gallery website 2018 [Online] Cited 01/01/2019

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

Un-Dividing History (details)

2017

Akram Zaatari (Lebanese, b. 1966)

History (detail)

2018

Installation view, Akram Zaatari: The Fold – Space, time and the image

© Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH, 2018

Photo: Tony Walsh

History retraces Zaatari’s pursuit of damaged, erased, withdrawn or scrapped off photographic descriptions from the nineties until the present day. The earliest is a self-portrait he made in 1993, and the most recent are part of Photographic Phenomena, 2018 series.

Contemporary Arts Center

Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art

44 E. 6th Street, Cincinnati, OH 45202

Phone: 513 345 8400

Opening hours:

10am – 4pm

Monday and Tuesday: Closed (shop open 10am – 2.30pm)

Wednesday – Friday: 10am – 7pm

Saturday and Sunday: 10am – 4pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.