Exhibition dates: 21st October, 2016 – 22nd January, 2017

Curators: Margaret Andera, adjunct curator of contemporary art at the Milwaukee Art Museum, Milwaukee and Britt Salvesen, Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s curator of the department of prints and drawings and the department of photography

Unknown photographer(s)

Set photograph from Fritz Lang’s “The Nibelungen: The Death of Siegfried (Die Nibelungen: Siegfrieds Tod)”

1923

Gelatin silver print

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

The interwar years of the European avant-garde are some of the most creative years in the history of the human race.

Whether because of political and social instability – the aftershocks of the First World War, the hardships, the looming fight between Communism and Fascism, the Great Depression – or the felt compression and compaction of time and space taking place all over Europe (as artists fled Russia, as artists fled Germany for anywhere but Germany, as though time was literally running out… as it indeed was), these years produced a frenzy of creativity in writing, film, design, architecture and all the arts.

The “avant-garde” produced new and experimental ideas and methods in art, music, and literature, the avant-garde literally being the “vanguard” of an army of change, producing for so very brief an instant, a bright flowering of camp, cabaret, and kitsch paralleled? intertwined with a highly charged emotionalism which, in German Expressionist film, “employed geometrically skewed set designs, dramatic lighting, off-kilter framing, strong shadows and distorted perspectives to express a sense of uneasiness and discomfort.”

Here we find the catalyst for subsequent film genres, most notably science fiction, horror and film noir. Here we find dark fantasies, desire, love and redemption. All to be swept away with the rushing rushing rushing tide of prejudice and persecution, of death and destruction that was to envelop the world during the Second World War.

The creative legacy of this period, however, is still powerful and unforgettable. I just have to look at the photographic stills of Metropolis to recognise what a visionary period it was, and how that film and others have stood the test of passing time (as the hands of the workers move the clock hands to their different positions in Metropolis). The feeling and aesthetic of the art remains as fresh as the day it was created.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Milwaukee Art Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

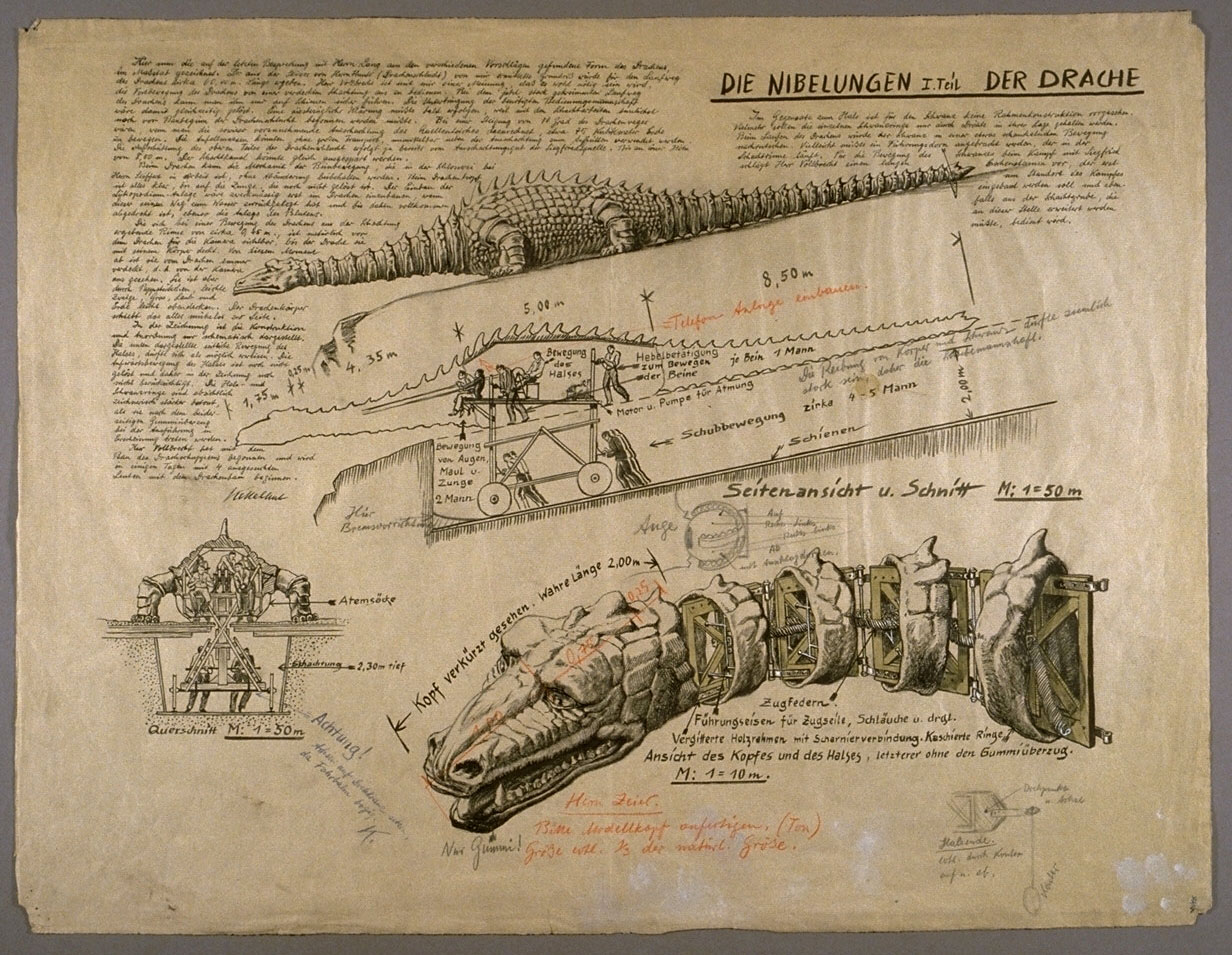

Siegfried’s Dragon

Unknown photographer(s)

Set photograph from Fritz Lang’s “The Nibelungen: The Death of Siegfried (Die Nibelungen: Siegfrieds Tod)”

1923

Gelatin silver print

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo courtesy Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

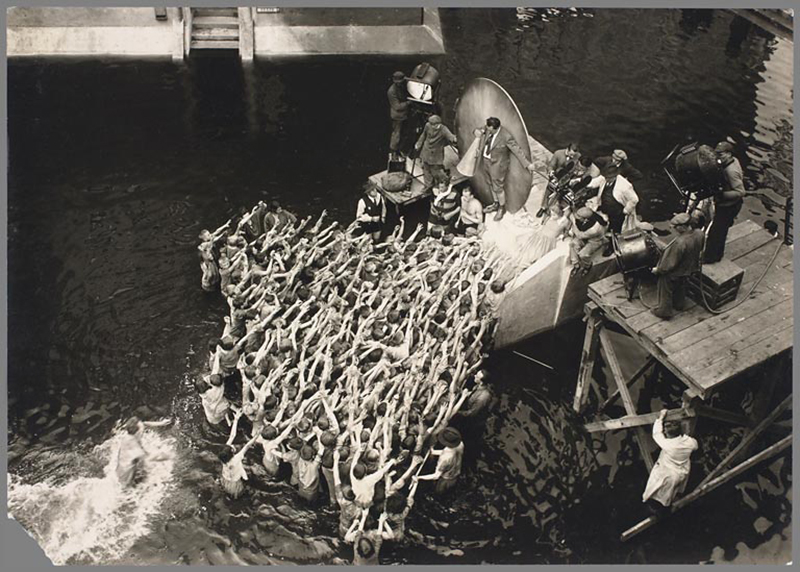

Unknown photographer(s)

Set photograph from Fritz Lang’s “The Nibelungen: The Death of Siegfried (Die Nibelungen: Siegfrieds Tod)”

1923

Gelatin silver print

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Fritz Lang (Austrian, 1890-1976)

… In this first phase of his career, Lang alternated between films such as Der Müde Tod (“The Weary Death”) and popular thrillers such as Die Spinnen (“The Spiders”), combining popular genres with Expressionist techniques to create an unprecedented synthesis of popular entertainment with art cinema.

In 1920, he met his future wife, the writer and actress Thea von Harbou. She and Lang co-wrote all of his movies from 1921 through 1933, including Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (Dr. Mabuse the Gambler; 1922), which ran for over four hours in two parts in the original version and was the first in the Dr. Mabuse trilogy, the five-hour Die Nibelungen (1924), the famous 1927 film Metropolis, the science fiction film Woman in the Moon (1929), and the 1931 classic, M, his first “talking” picture.

Considered by many film scholars to be his masterpiece, M is a disturbing story of a child murderer (Peter Lorre in his first starring role) who is hunted down and brought to rough justice by Berlin’s criminal underworld. M remains a powerful work; it was remade in 1951 by Joseph Losey, but this version had little impact on audiences, and has become harder to see than the original film. During the climactic final scene in M, Lang allegedly threw Peter Lorre down a flight of stairs in order to give more authenticity to Lorre’s battered look. Lang, who was known for being hard to work with, epitomised the stereotype of the tyrannical German film director, a type embodied also by Erich von Stroheim and Otto Preminger. His wearing a monocle added to the stereotype.

In the films of his German period, Lang produced a coherent oeuvre that established the characteristics later attributed to film noir, with its recurring themes of psychological conflict, paranoia, fate and moral ambiguity. At the end of 1932, Lang started filming The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Adolf Hitler came to power in January 1933, and by March 30, the new regime banned it as an incitement to public disorder. Testament is sometimes deemed an anti-Nazi film as Lang had put phrases used by the Nazis into the mouth of the title character.

Lang was worried about the advent of the Nazi regime, partly because of his Jewish heritage, whereas his wife and screenwriter Thea von Harbou had started to sympathise with the Nazis in the early 1930s and joined the NSDAP in 1940. They soon divorced. Lang’s fears would be realised following his departure from Austria, as under the Nuremberg Laws he would be identified as a Jew even though his mother was a converted Roman Catholic, and he was raised as such.

Shortly afterwards, Lang left Germany. According to Lang, propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels called Lang to his offices to inform him that The Testament of Dr Mabuse was being banned but that he was nevertheless so impressed by Lang’s abilities as a filmmaker (especially Metropolis), he was offering Lang a position as the head of German film studio UFA. Lang had stated that it was during this meeting that he had decided to leave for Paris – but that the banks had closed by the time the meeting was over. Lang has stated that he fled that very evening. …

In Hollywood, Lang signed first with MGM Studios. His first American film was the crime drama Fury, which starred Spencer Tracy as a man who is wrongly accused of a crime and nearly killed when a lynch mob sets fire to the jail where he is awaiting trial. Lang became a naturalised citizen of the United States in 1939. He made twenty-three features in his 20-year American career, working in a variety of genres at every major studio in Hollywood, and occasionally producing his films as an independent. Lang’s American films were often compared unfavourably to his earlier works by contemporary critics, but the restrained Expressionism of these films is now seen as integral to the emergence and evolution of American genre cinema, film noir in particular. Lang’s film titled in 1945 as Scarlet Street is considered a central film in the genre.

One of his most famous films noir is the police drama The Big Heat (1953), noted for its uncompromising brutality, especially for a scene in which Lee Marvin throws scalding coffee on Gloria Grahame’s face. As Lang’s visual style simplified, in part due to the constraints of the Hollywood studio system, his worldview became increasingly pessimistic, culminating in the cold, geometric style of his last American films, While the City Sleeps (1956) and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956).

Text from the Wikipedia website

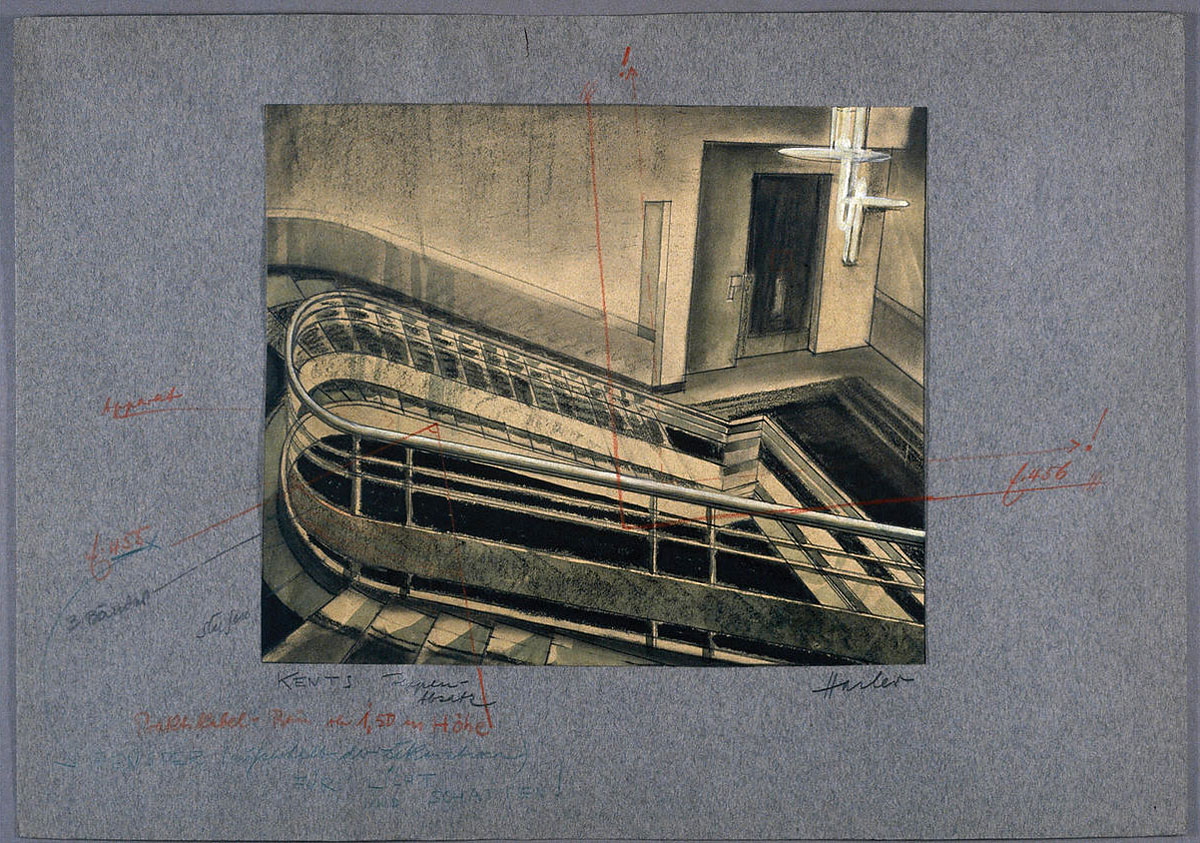

Otto Hunte (German, 1881-1950) and Fritz Lang (German, 1890-1976)

Set design drawing for “The Nibelungen: The Death of Siegfried (Die Nibelungen: Siegfrieds Tod)”

1923

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Otto Hunte (German, 1881-1950) and Fritz Lang (German, 1890-1976)

Set design drawing for “The Nibelungen: The Death of Siegfried (Die Nibelungen: Siegfrieds Tod)”

1923

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Caspar David Friedrich (German, 1774-1840)

Two Men Contemplating the Moon

c. 1825-1830

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wrightsman Fund, 2000

Photo: courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art

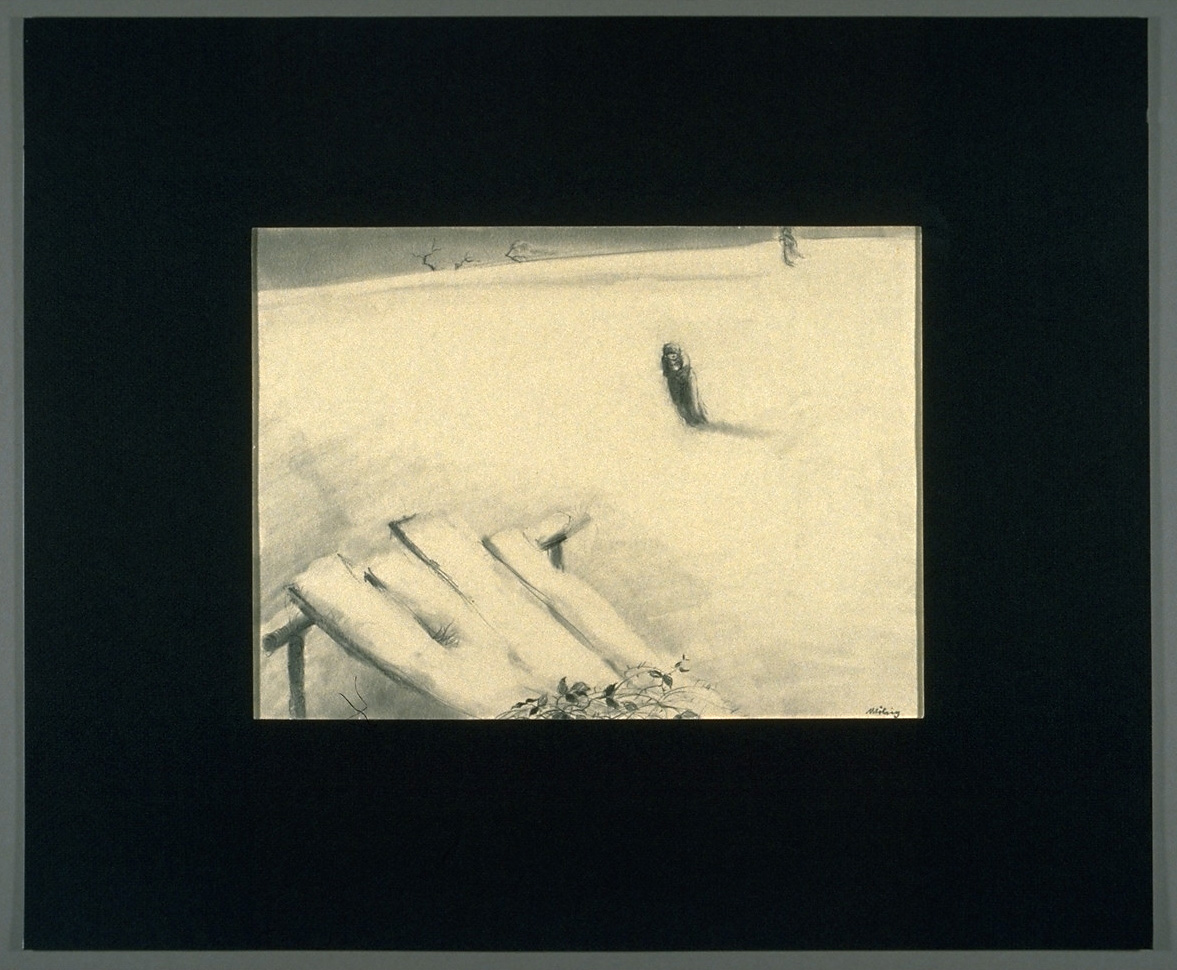

Erich Kettelhut (German, 1893-1979) and Fritz Lang (German, 1890-1976)

Set design drawing for “The Nibelungen: The Death of Siegfried (Die Nibelungen: Siegfrieds Tod)”

1923

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo courtesy Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

In the wake of WWI, while Hollywood and the rest of Western cinema were focused mostly on adventure, romance and comedy, German filmmakers explored the anxiety and emotional turbulence that dominated life in Germany. They took their inspiration from Expressionist art and employed geometrically skewed sets, dramatic lighting, off-kilter framing, strong shadows and distorted perspectives.

The impact of this aesthetic has lasted nearly a century, inspiring directors from Alfred Hitchcock to Tim Burton. Its influence is reflected to this day in the dark, brooding styles of film noir, the unsettling themes of horror, and the fantastic imagery of sci-fi. From Blade Runner to The Godfather, from Star Wars to The Hunger Games – our modern blockbusters owe much to these German masters and the visions they created.

Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s explores masterworks of German Expressionist cinema, from the stylized fantasy of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to the chilling murder mystery M. Featured are production design drawings, photographs, posters, documents, equipment and film clips from more than 20 films. The exhibition ends with a contemporary 3-channel projection work – Kino Ektoplamsa, 2012 – by filmmaker Guy Maddin, which was inspired by German Expressionist cinema.

Text from the Milwaukee Art Museum website

Designed by USC architecture professor Amy Murphy and architect Michael Maltzan, “Haunted Screens” has been grouped by theme: “Madness and Magic,” “Myths and Legends,” “Cities and Streets” and “Machines and Murderers.” The latter contains a subsection, “Stairs,” that includes drawings from films that feature stairs as both a visual and psychological theme. Two darkened tunnels will feature excerpts from the movies highlighted in the exhibit.

“The core of the show is the collection from La Cinémathèque française,” said Britt Salvesen, LACMA’s curator of both the department of prints and drawings and the department of photography.

The 140 drawings from the Cinémathèque were acquired by noted German film historian Lotte Eisner, who wrote the 1952 book “The Haunted Screen.”

Josef Fenneker (Germany, 1895-1956)

Reissue of original poster for The Burning Soil (Der brennende acker)

c. 1922

Director: Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (German, 1888-1931)

Offset lithograph

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (German, 1888-1931)

Friedrich Wilhelm “F. W.” Murnau (born Friedrich Wilhelm Plumpe; December 28, 1888 – March 11, 1931) was a German film director. Murnau was greatly influenced by Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Shakespeare and Ibsen plays he had seen at the age of 12, and became a friend of director Max Reinhardt. During World War I he served as a company commander at the eastern front and was in the German air force, surviving several crashes without any severe injuries.

One of Murnau’s acclaimed works is the 1922 film Nosferatu, an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Although not a commercial success due to copyright issues with Stoker’s novel, the film is considered a masterpiece of Expressionist film. He later directed the 1924 film The Last Laugh, as well as a 1926 interpretation of Goethe’s Faust. He later emigrated to Hollywood in 1926, where he joined the Fox Studio and made three films: Sunrise (1927), 4 Devils (1928) and City Girl (1930). The first of these three is widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made.

In 1931 Murnau travelled to Bora Bora to make the film Tabu (1931) with documentary film pioneer Robert J. Flaherty, who left after artistic disputes with Murnau, who had to finish the movie on his own. A week prior to the opening of the film Tabu, Murnau died in a Santa Barbara hospital from injuries he had received in an automobile accident that occurred along the Pacific Coast Highway near Rincon Beach, southeast of Santa Barbara.

Of the 21 films Murnau directed, eight are considered to be completely lost. One reel of his feature Marizza, genannt die Schmuggler-Madonna survives. This leaves only 12 films surviving in their entirety.

Text from the Wikipedia website

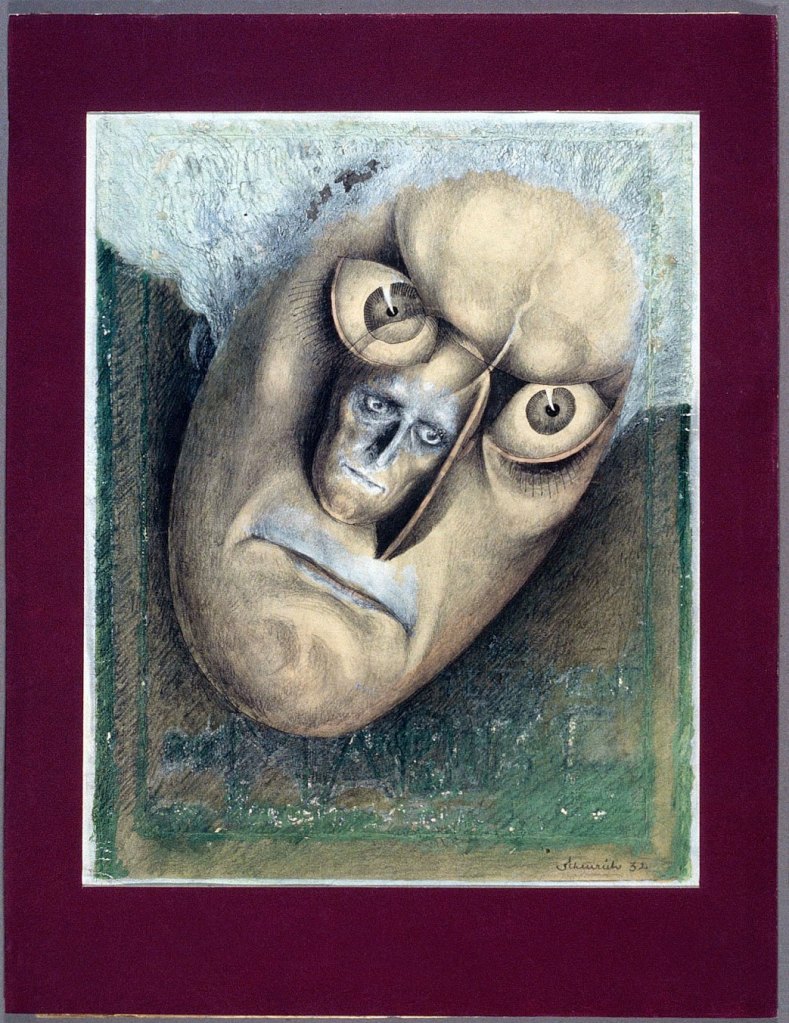

Hermann Warm (German, 1889-1976) and Henrik Galeen (Austrian, 1881-1949)

Drawing for “Der Student von Prag” (The Student of Prague)

1926

Pastel

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris/LACMA

Andrei Andrejew (Russia, 1887-1966)

Set design drawing for Crime and Punishment (Raskolnikow)

1923

Director: Robert Wiene (Germany, 1873-1938)

Ink and ink wash

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Raskolnikow is a 1923 German silent drama film directed by Robert Wiene. The film is based on the novel Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, whose protagonist is Rodion Raskolnikov. The film’s art direction is by André Andrejew. The film is characterised by Jason Buchanan of Allmovie as a German expressionist view of the story: a “nightmarish” avante-garde or experimental psychological drama.

Robert Wiene (German, 1873-1938)

Robert Wiene (German, 27 April 1873 – 17 July 1938) was a film director of the German silent cinema. He is particularly known for directing the German silent film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and a succession of other expressionist films. Wiene also directed a variety of other films of varying styles and genres. Following the Nazi rise to power in Germany, Wiene fled into exile.

Four months after the Nazis took power Wiene’s latest film, “Taifun,” was banned on May 3, 1933. A Hungarian film company had been inviting German directors to come to Budapest to make films in simultaneous German/Hungarian versions, and given his uncertain career prospects under the new German regime Wiene took up that offer in September to direct “One Night in Venice” (1934). Wiene went later to London, and finally to Paris where together with Jean Cocteau he tried to produce a sound remake of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. …

Wiene died in Paris ten days before the end of production of a spy film, Ultimatum, after having suffered from cancer. The film was finished by Wiene’s friend Robert Siodmak.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Otto Erdmann (German, 1834-1905) and Georg Wilhelm Pabst (Austrian, 1885-1967)

Die Freudlose Gasse (The Joyless Street)

1923

Gouache and watercolour

Photo courtesy Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris/LACMA

Otto Erdmann (German, 1834-1905) and Georg Wilhelm Pabst (Austrian, 1885-1967)

Die Freudlose Gasse (The Joyless Street)

1923

Director: Georg Wilhelm Pabst

Gouache and watercolor

Photo courtesy Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris/LACMA

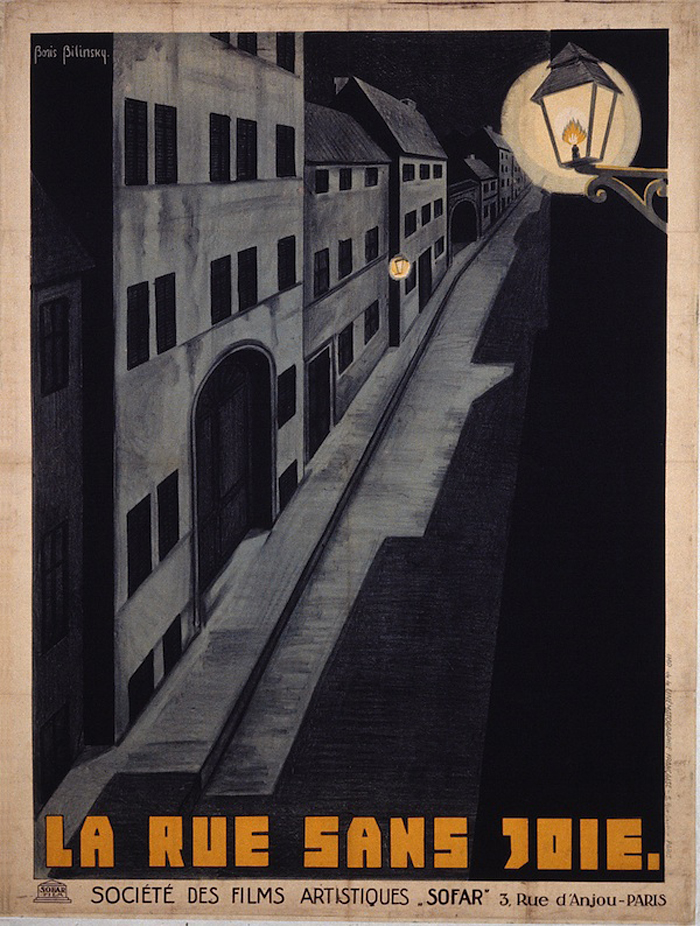

Boris Bilinsky (Russia, 1900-1948)

Poster for The Joyless Street (Die freudlose Gasse)

c. 1925

Director: Georg Wilhelm Pabst (Austria, 1885-1967)

Lithograph

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Walter Röhrig (German, 1892-1945) and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (German, 1888-1931)

Faust

1926

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

© 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Photo courtesy Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Robert Herlth (German, 1893-1962) and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (German, 1888-1931)

Faust

1926

Director: Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo courtesy Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Robert Herlth (German, 1893-1962) and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (German, 1888-1931)

Faust

1926

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo courtesy Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Robert Herlth (German, 1893-1962) and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (German, 1888-1931)

Faust

1926

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Photo courtesy Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Robert Herlth (German, 1893-1962) and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau (German, 1888-1931)

Drawing for “Faust”

1926

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Unknown photographer

Set photograph from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (Das Kabinett des Dr. Caligari)

1919

Director: Robert Wiene (German, 1873-1938)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies

Hermann Warm (German, 1889-1976)

Robert Wiene’s “Das Kabinett des Dr Caligari”

1919

Watercolour and ink

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Set drawing for the”Das Kabinett des Dr Caligari” (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari)

1920

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Ernst Stern (Romanian-German, 1876-1954)

Paul Leni’s “Das Wachfigurenkabinett (Le cabinet des figures de cire)” (Wax Works)

1924

Director: Paul Leni

Watercolour and charcoal

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris/LACMA

Ernst Stern (Romanian-German, 1876-1954) and Paul Leni (German, 1885-1929)

“Das Wachfigurenkabinett (Le cabinet des figures de cire)” (Wax Works)

1924

Watercolour, gouache, and graphite

34.6 x 24.8cm

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris/LACMA

Unknown photographer

Set photograph from “The Blue Angel” (Der blaue Engel)

1930

Director: Josef von Sternberg (Austria, 1894-1969)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Karl Struss (American, 1886-1981)

Set photograph from “Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans” (Sonnenaufgang: Ein Lied zweier Menschen) (detail)

1927, printed 2014

Directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau

Courtesy of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Margaret Herrick Library

Emil Hasler (German, 1901-1986)

Drawing for Fritz Lang’s “Das Testament des Dr Mabuse” (The Testament of Dr Mabuse)

1932

Pastel, graphite, and gouache

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris/LACMA

Paul Scheurich (German, 1883-1945)

Poster design for Fritz Lang’s “Das Testament des Dr Mabuse” (The Testament of Dr Mabuse)

1932

Ink, gouache, and graphite

BiFi, Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Emil Hasler (German, 1901-1986)

Drawing for Fritz Lang’s “M,” le Maudit (Cursed)

1931

Charcoal, gouache, and coloured pencil

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris/LACMA

Unknown artist

Poster for “M”

1931

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Unknown artist

Poster for “M”

1933

Made for Paramount release in Los Angeles

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Courtesy of Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ Margaret Herrick Library

The Milwaukee Art Museum is excited for visitors to experience its newest exhibition, Haunted Screens: German Cinema in the 1920s on view from Oct. 21 through Jan. 22. Organised by La Cinémathèque française, Paris, the exhibition examines the groundbreaking period in film history that occurred in Germany during the Weimar era after World War I, through more than 150 objects, including set design drawings, photographs, posters, documents, equipment, cameras and film clips from more than 20 films.

The Expressionist movement introduced a highly charged emotionalism to the artistic disciplines of painting, photography, theater, literature and architecture, as well as film, in the early part of the 20th century. German filmmakers employed geometrically skewed set designs, dramatic lighting, off-kilter framing, strong shadows and distorted perspectives to express a sense of uneasiness and discomfort. These films reflected the mood of Germany during this time, when Germans were reeling from the death and destruction of WWI and were enduring hyperinflation and other hardships.

“We’re thrilled to present Haunted Screens at the Milwaukee Art Museum this fall, and to offer our visitors a glimpse into a unique and revolutionary time in film and art history,” said Margaret Andera, the Museum’s adjunct curator of contemporary art. “This exhibition represents a tremendous period of creativity, and allows visitors a fascinating look at the nuanced aesthetics of German Expressionist cinema through a wealth of diverse objects.”

The exhibition is grouped into five sections by theme: Nature, Interiors, The Street, Staircases and The Expressionist Body. From the dark fantasy of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to the chilling murder mystery M, the exhibition explores masterworks of German Expressionist cinema in aesthetic, psychological and technical terms. More than 140 drawings are complemented by some 40 photographs, eight projected film clip sequences, numerous film posters, three cameras, one projector, and a resin-coated, life-size reproduction of the Maria robot from Metropolis.

German Expressionist cinema was the first self-conscious art cinema, influencing filmmakers throughout the world at the time and continuing to inspire artists today. It served as a catalyst for subsequent film genres, most notably science fiction and horror. The conflicting attitudes about technology and the future that are the cornerstones of science fiction, and the monsters and villains that form the basis of horror, appear often in Expressionist films. The influence of Expressionist cinema undoubtedly extends to the work of contemporary filmmakers, including Tim Burton, Martin Scorsese and Guy Maddin, whose 3-channel projection work, Kino Ektoplamsa, appears at the end of the exhibition.

The Museum is taking a unique approach to the exhibition’s installation design, one that mirrors the mood of the time and the objects on display. Walls intersecting at unexpected angles and even breaking through the exhibition space into Windhover Hall give visitors an engaging experience.

The Milwaukee Art Museum’s permanent collection includes extensive holdings in the German Expressionist area, including a significant collection of paintings from the period, as well as one of the most important collections of German Expressionist prints in the nation, the Marcia and Granvil Specks Collection. This collection includes more than 450 prints by German masters. Visitors are encouraged to stroll through the collection galleries after seeing Haunted Screens.”

Press release from the Milwaukee Art Museum

Metropolis (1927) full movie

Synopsis of Metropolis

Metropolis is ruled by the powerful industrialist Joh Fredersen. He looks out from his office in the Tower of Babel at a modern, highly technicised world. Together with the children of the workers, a young woman named Maria reaches the Eternal Gardens where the sons of the city’s elite amuse themselves and where she meets Freder, Joh Fredersen’s son. When the young man later goes on a search for the girl, he witnesses an explosion in a machine hall, where numerous workers lose their lives. He then realises that the luxury of the upper class is based on the exploitation of the proletariat. In the Catacombs under the Workers’ City Freder finally finds Maria, who gives the workers hope with her prophecies for a better future. His father also knows about Maria’s influence on the proletariat and fears for his power. In the house of the inventor Rotwang, Joh Fredersen learns about his experiments to create a cyborg based on the likeness of Hel, their mutual love and Freder’s mother. Fredersen orders Rotwang to give Maria’s face to the robot in order to send it to the underground city to deceive and stir up its inhabitants.

After the robot Maria has succeeded, a catastrophe ensues. The riotous workers destroy the Heart Machine and as a result the Workers’ City, where only the children have remained, is terribly flooded. The real Maria brings the children to safety along with Freder. When they learn about the disaster, the rebelling masses stop. Their rage is now aimed at the robot Maria, who is captured and burned at the stake. At the same time Rotwang, driven by madness, pursues the genuine Maria across the Cathedral’s rooftop, where he ultimately falls to his death. Freder and Maria find each other again. The son devotes himself to his father, mediating between him and the workers. As a consequence, Maria’s prophecy of reconciliation between the ruler and those who are mastered (head and hands) triumphs – through the help of the mediating heart.

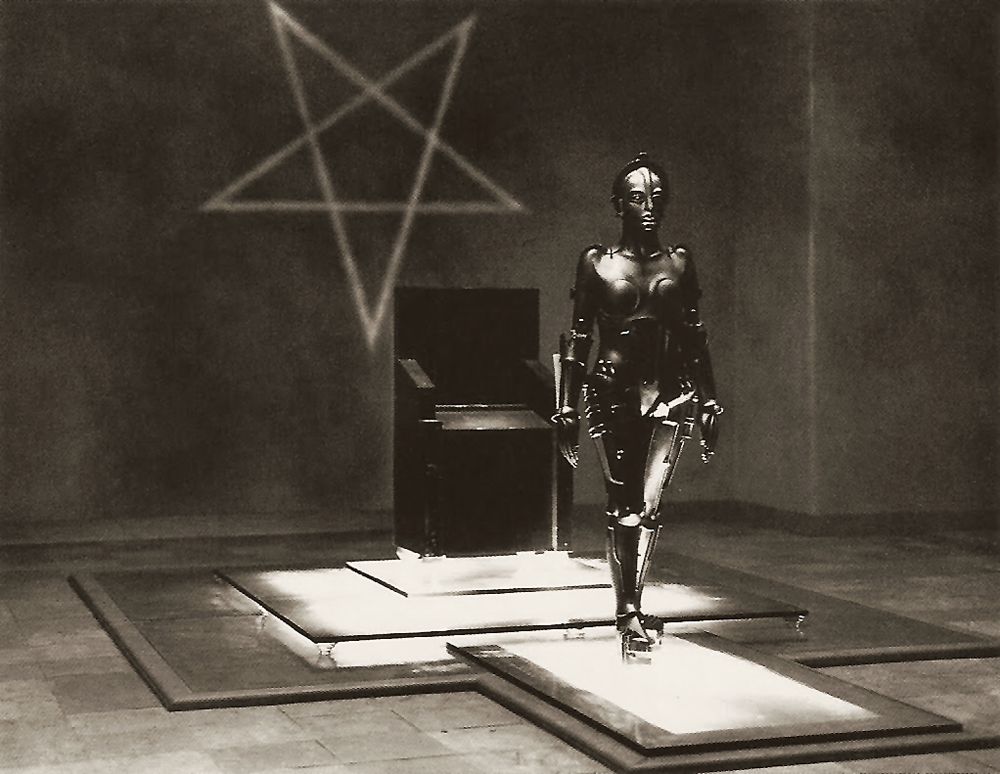

Horst von Harbou (Germany, 1879-1953)

Set photograph from “Metropolis”

1927

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Horst von Harbou (Germany, 1879-1953)

Set photograph from “Metropolis”

1927

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Horst von Harbou (Germany, 1879-1953)

Set photograph from “Metropolis”

1927

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Horst von Harbou (Germany, 1879-1953)

Set photograph from “Metropolis”

1927

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Horst von Harbou (Germany, 1879-1953)

Set photograph from “Metropolis”

1927

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Horst von Harbou (Germany, 1879-1953)

Set photograph from “Metropolis”

1927

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Horst von Harbou (Germany, 1879-1953)

Set photograph from “Metropolis”

1927

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) is a defining film of the silent era and science fiction genre. But the work of the film’s still photographer Horst von Harbou has remained obscure. Von Harbou, brother of Thea von Harbou, Lang’s then wife and co-screenwriter of Metropolis, photographed filmed scenes as well as off-camera action, and made an album of thirty-five photographs which he gave to the film’s young star Brigitte Helm. The book Metropolis is a careful reconstruction of this album, showing the photographs and some of their backsides which feature hand-written notes. Von Harbou’s photographs not only offer a rare insight into Lang’s film, but have been crucial in reconstructing missing scenes from it.

Horst von Harbou was born in 1879 in Hutta, Posen, and died in 1953 in Potsdam-Babelsberg. Very little is known about von Harbou, except for the films on which he worked as a still photographer: these include Mensch ohne Namen (1932), Starke Herzen im Sturm (1937) and Augen der Liebe (1951).

Text from the Steidl Books website

Horst von Harbou (Germany, 1879-1953)

Set photograph from “Metropolis” (detail)

1927

Director: Fritz Lang (Austria, 1890-1976)

Gelatin silver print

Collection of La Cinémathèque française

Otto Hunte (German, 1881-1960)

Set design drawing for “Metropolis”

1923

Director: Fritz Lang

Collection of La Cinémathèque française, Paris

Otto Hunte (German, 1881-1960)

Otto Hunte (9 January 1881 – 28 December 1960) was a German production designer, art director and set decorator. Hunte is considered as one of the most important artists in the history of early German cinema, mainly for his set designs on the early silent movies of Fritz Lang. His early career was defined by a working relationship with fellow designers Karl Vollbrecht and Erich Kettelhut. Hunte’s architectural designs are found in many of the most important films of the period including Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, Die Nibelungen (1924), Metropolis (1927) and Der blaue Engel. Hunte subsequently worked as one of the leading set designers during the Nazi era. Post-Second World War he was employed by the East German studio DEFA.

Paramount

Trade advertisement for “Metropolis”

1927

Lithograph

Milwaukee Art Museum

700 N Art Museum Dr,

Milwaukee WI 53202

Opening hours:

Monday – Tuesday Closed

Wednesday 10am – 5pm

Thursday 10am – 8pm

Friday – Sunday 10am – 5pm

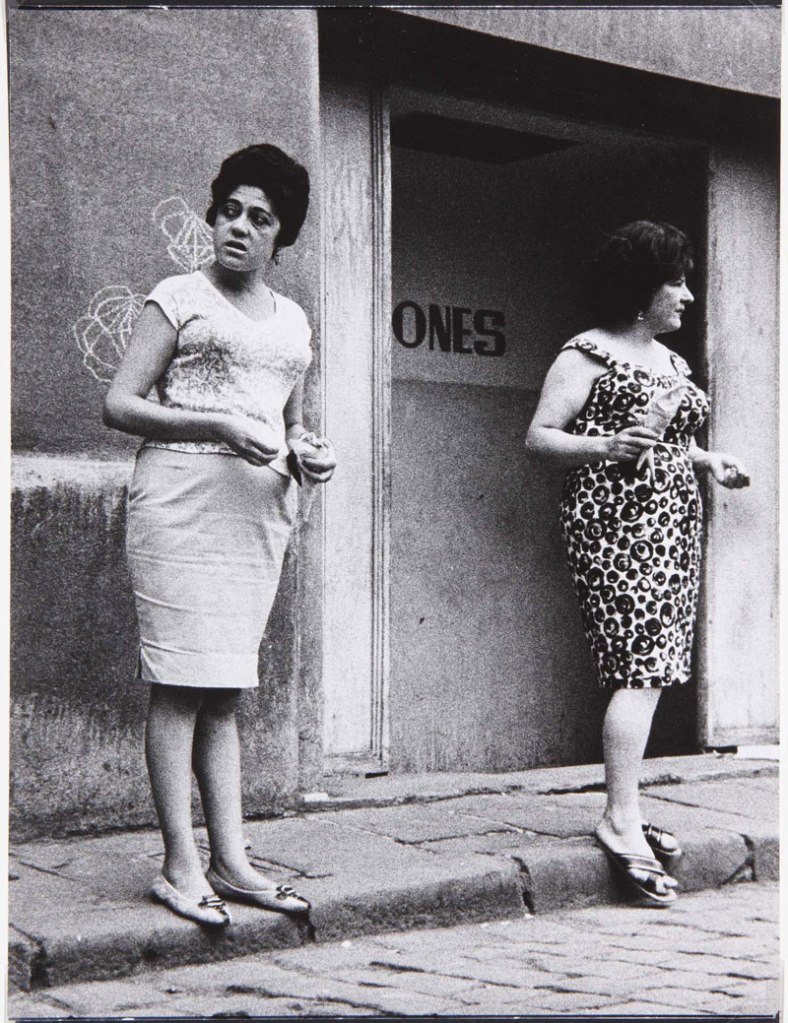

![Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'La actual M-30 (Madrid)' (The M-30 Ring Road Today [Madrid]) 1963 (May) / posthumous print, 2013 Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'La actual M-30 (Madrid)' (The M-30 Ring Road Today [Madrid]) 1963 (May) / posthumous print, 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/francisco-ontac3b1c3b3n-la-actual-m-30-madrid-web.jpg)

![Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Sans Titre (Madrid)' (No Title [Madrid]) 1963 (May) / posthumous print, 2013 Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Sans Titre (Madrid)' (No Title [Madrid]) 1963 (May) / posthumous print, 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/francisco-ontac3b1c3b3n-s_t-madrid-web.jpg)

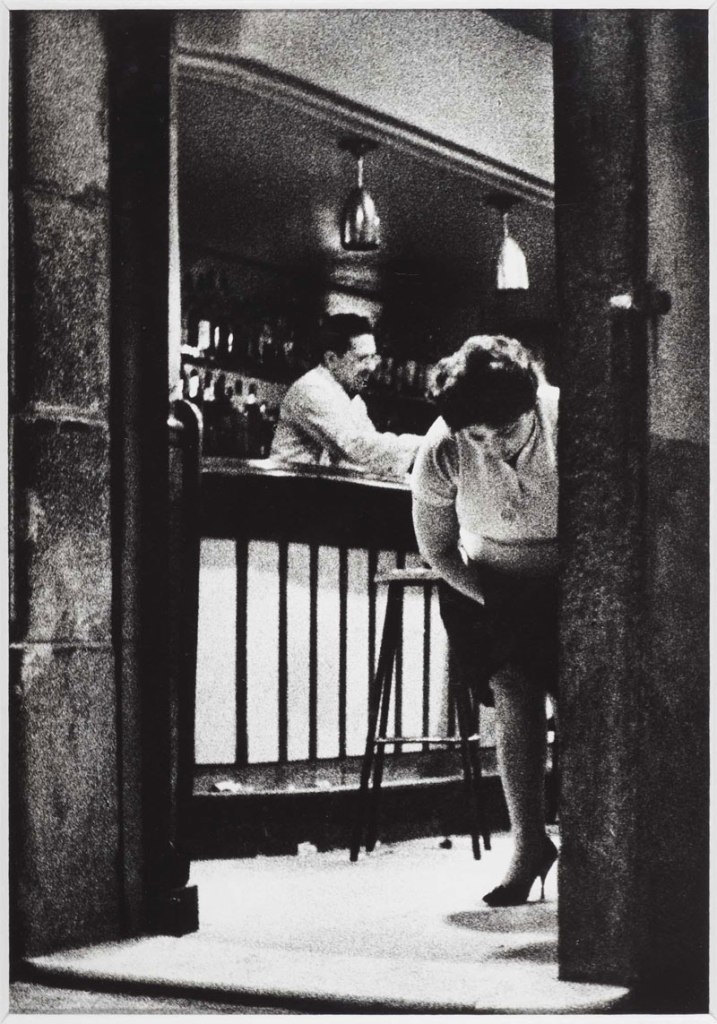

![Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Sans Titre (Madrid)' (No Title [Madrid]) 1964-65 / posthumous print, 2013 Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Sans Titre (Madrid)' (No Title [Madrid]) 1964-65 / posthumous print, 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/francisco-ontac3b1c3b3n-s_t-madrid-b-web.jpg)

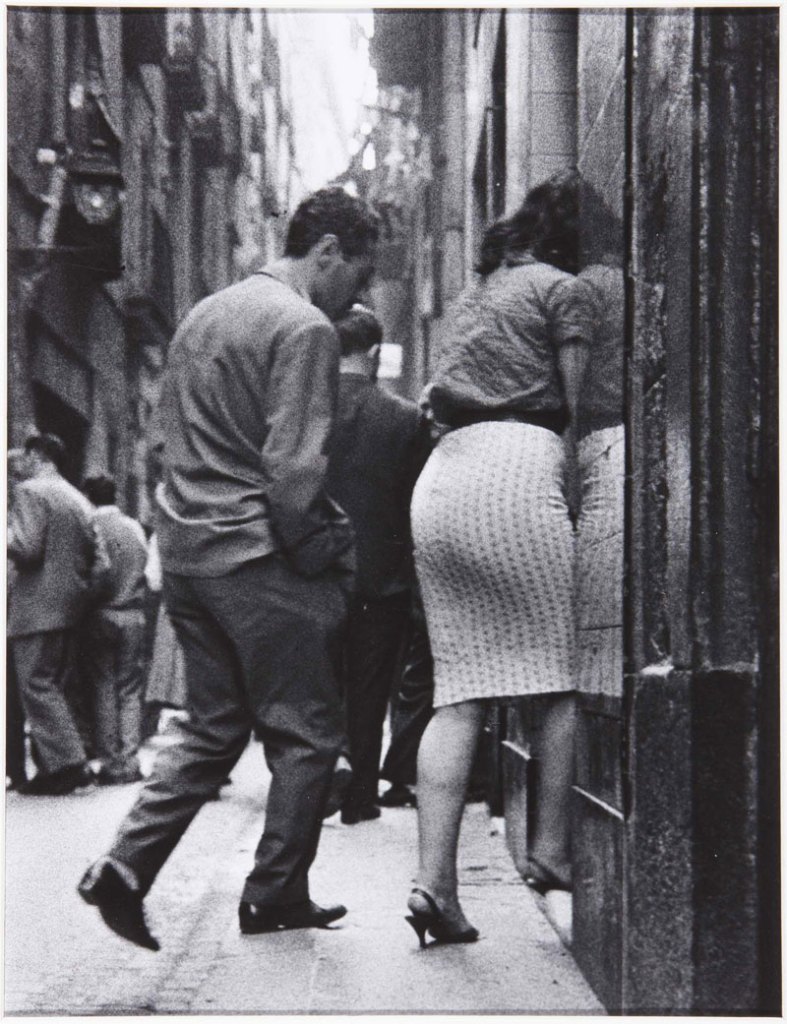

![Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Sans Titre (Madrid)' (No Title [Madrid]) 1964-65 / posthumous print, 2013 Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Sans Titre (Madrid)' (No Title [Madrid]) 1964-65 / posthumous print, 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/francisco-ontac3b1c3b3n-s_t-madrid-c-web.jpg)

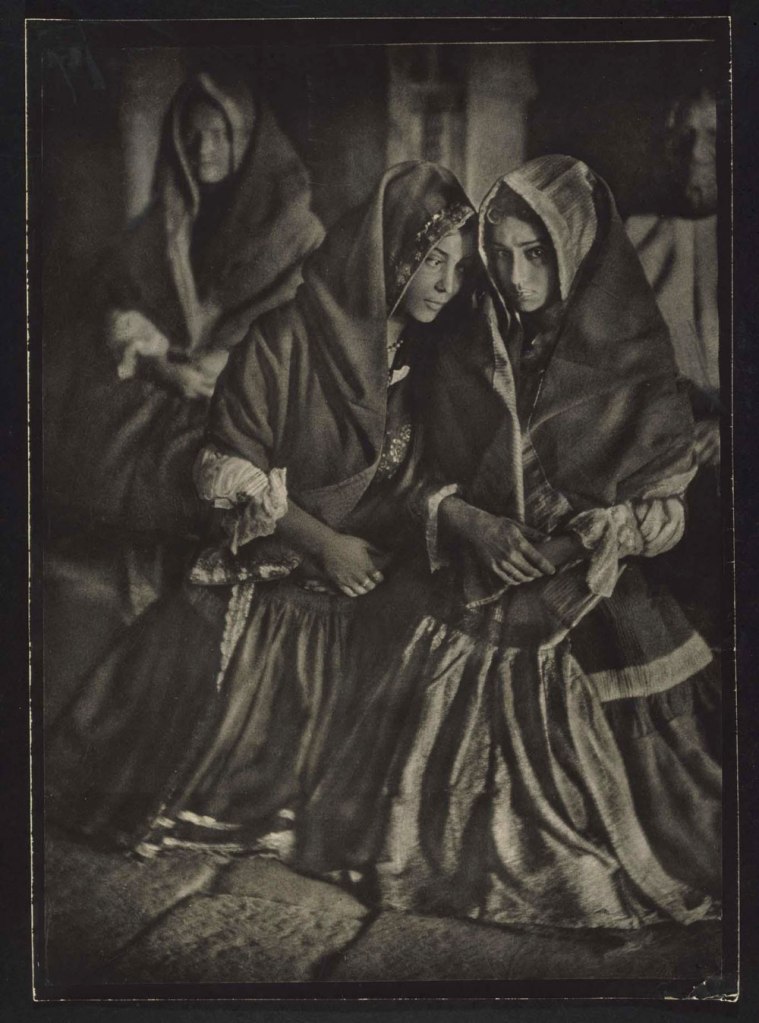

![Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Sans Titre (Madrid)' (No Title [Madrid]) 1964 / posthumous print, 2013 Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Sans Titre (Madrid)' (No Title [Madrid]) 1964 / posthumous print, 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/francisco-ontac3b1c3b3n-s_t-madrid-d-web.jpg)

![Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) '600 en Casa de Campo con familia (Madrid)' (Outing to Casa de Campo in the 600, with Family [Madrid]) 1963 (May) / posthumous print, 2013 Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) '600 en Casa de Campo con familia (Madrid)' (Outing to Casa de Campo in the 600, with Family [Madrid]) 1963 (May) / posthumous print, 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/francisco-ontac3b1c3b3n-600-en-casa-de-campo-web.jpg)

![Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Parque Sindical (Madrid)' (Parque Sindical Sports Area [Madrid]) 1964 / posthumous print, 2013 Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Parque Sindical (Madrid)' (Parque Sindical Sports Area [Madrid]) 1964 / posthumous print, 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/francisco-ontac3b1c3b3n-parque-sindical-madrid-web.jpg)

![Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Entierro (Madrid)' (Burial [Madrid]) 1967 / posthumous print, 2013 Francisco Ontañón (Barcelona, Spain, 1930 - Madrid, Spain, 2008) 'Entierro (Madrid)' (Burial [Madrid]) 1967 / posthumous print, 2013](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/francisco-ontac3b1c3b3n-entierro-madrid-web.jpg)

![Agustí Centelles (Catalan, 1909-1985) 'Barcelona, España. Guardería infantil en Vía Layetana' [Babysitting in Layetana Road] 1936-1939 Agustí Centelles (Catalan, 1909-1985) 'Barcelona, España. Guardería infantil en Vía Layetana' [Babysitting in Layetana Road] 1936-1939](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/agusti_centelles-guarderia_infantil-web.jpg)

![Fernand Léger (French, 1881-1951) 'Les Loisirs - Hommage à Louis David' [Leisure - Homage to Louis David] 1948-1949 Fernand Léger (French, 1881-1951) 'Les Loisirs - Hommage à Louis David' [Leisure - Homage to Louis David] 1948-1949](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/leger-les_loisirs-web.jpg)

![Louis Sciarli (French, b. 1925) 'Le Corbusier. Marseille: Unité d'habitation, École Maternelle' [Le Corbusier. Marseille: housing unit, Kindergarten] 1945/2014 Louis Sciarli (French, b. 1925) 'Le Corbusier. Marseille: Unité d'habitation, École Maternelle' [Le Corbusier. Marseille: housing unit, Kindergarten] 1945/2014](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/sciarli-le_corbusier_marseille-web.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.