Exhibition dates: 9th April – 7th July 2024

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker

Cover of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”]

1839-1855

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Shock of the new

At the moment the archive is going through a veritable feast of wonderful exhibitions on 19th century photography, this exhibition at the Getty a companion to last week’s posting on the exhibition Nineteenth-Century Photography Now also at the J. Paul Getty Museum. What a delight!

This posting on the important photographer and inventor Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) – one of the pioneers of photography who was finally acknowledged as such during his lifetime and received due recognition – offers the visitor the opportunity to view fragile photographs from the Getty’s treasured Bayard album, one of the first photographic albums ever created, before the leaves of the album are reassembled after restoration.

“The album includes 145 of Bayard’s experiments with different photographic processes on paper, primarily salted paper prints from paper negatives from about 1839 to the late 1840s… Bayard divided the album into four sections: still lifes, portraits, urban and rural landscapes, and an assortment of miscellaneous images. The inclusion of twenty-two photographs by British photographers, including William Henry Fox Talbot, provides evidence of Bayard’s interactions with his fellow pioneers across the English Channel. …

Inscriptions found on the Getty album pages and versos of its photographs support the theory that the artist himself – or someone with firsthand knowledge of the chemicals he used – compiled this volume. Thus, this treasure offers intriguing insights into Bayard’s practice, aesthetic choices, and strategies for presenting himself through the order and arrangement of the photographs.”1

The full album and layout can be viewed on the Getty’s website.

What I find delightful about this “album of experiments” – other than Bayard’s perceptive, inquisitive self-portraits and delicate, atmospheric cyanotype and salted paper print photograms – is the colour (including hand coloured), size and placement of the photographic prints on the pages of the album. Sometimes gridded, sometimes singular in grand isolation, sometimes asymmetrical with empty pages between images, the album seems to flow allow like a river… only for the viewer then to have to change orientation, as vertical images on one page are then abutted next to a page of images that need to be viewed in a horizontal format but turning the album through 90 degrees.

It’s as if the compiler of the album, probably Bayard himself, applied this prick of consciousness to the viewing of the album, to stop the viewer skimming over the images but forcing them to be attentive, to be aware, of the progression of the story that the artist was telling, to be aware of a certain “disposition” in the viewer in order to – a/ disrupt the tendency of something to act in a certain manner under given circumstances and b/ impinge on a person’s inherent quality of mind and character. To offer a new dispensation on reality.

In other words, the artist challenges the viewer as to how photographs are read and interpreted through changes to the perception and point of view said “reader”. I don’t think I have ever seen such an early photo book that proposes such a daring reorientation of consciousness as does this album.

New technologies, new aesthetics, new dispositions.

The shock of the new.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs, 2024

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Parisian bureaucrat by day and tireless inventor after hours, Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) was one of the most important, if lesser-known, pioneers of photography. During his thirty-year career, he invented the direct positive process and several other photographic techniques on paper. This exhibition presents an extraordinarily rare opportunity to view some of Bayard’s highly fragile photographs dating from the 1840s – the first decade of the new medium. The exhibition journeys back to the 19th century to unveil a collection of Bayard’s delicately crafted photographs, offering an extraordinarily rare glimpse into his unique processes, subjects, and persistent curiosity. He brought an artistic sensitivity into capturing the first staged self-portraits and set precedents for photography as we know it today. It highlights Getty’s treasured Bayard album, one of the first photographic albums ever created.

This exhibition is presented in English and Spanish.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker

Title page of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] with Hippolyte Bayard’s [Self-Portrait in the Garden] June 1845

1839-1855

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Text above the photograph: Bromure d’argent vapeurs de Mercure (Silver bromide Mercury vapors)

Hippolyte Bayard’s self-portrait at his garden gate [Self-Portrait in the Garden] introduces the contents of this 184-page album, one of the earliest photographic albums ever created…

Titled Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Receuil No. 2 [Photographic Drawings on Paper. Collection No. 2], the album includes 145 of Bayard’s experiments with different photographic processes on paper, primarily salted paper prints from paper negatives from about 1839 to the late 1840s. Twenty-two photographs by six of his British peers are also interspersed through the album. With its green-and-black marbled covers, it is similar in style to the other known album devoted to Bayard – Album d’essais [Album of Experiments] – owned by the Société française de photographie (SFP) in Paris. Inscriptions found on the Getty album pages and versos of its photographs support the theory that the artist himself – or someone with firsthand knowledge of the chemicals he used – compiled this volume. Thus, this treasure offers intriguing insights into Bayard’s practice, aesthetic choices, and strategies for presenting himself through the order and arrangement of the photographs.

Bayard divided the album into four sections: still lifes, portraits, urban and rural landscapes, and an assortment of miscellaneous images. The inclusion of twenty-two photographs by British photographers, including William Henry Fox Talbot, provides evidence of Bayard’s interactions with his fellow pioneers across the English Channel.

This album has passed through several owners over its 180-plus year life. While gaps still exist, we have traced much of its provenance, or history of ownership. Working back in time, the Getty Museum purchased the album in 1984 from the American collector Arnold Crane (1932-2014) as part of its foundational photography collection. Crane had acquired it in 1970 from Alain Brieux (1922-1985), a Parisian book dealer. By the early 1950s, the album was in the possession of the commune of Breteuil-sur-Noye, Bayard’s hometown, or its mayor, François Monnet (1890-1970). A member of Bayard’s extended family may have given or sold the album to Breteuil. Moving further back into the nineteenth century, Bayard’s family likely chose to keep the album at the time of his death in 1887. We believe that Bayard possessed the album from its creation until he passed away.

Over time different individuals have added inscriptions, numbering systems, correspondence, a biography, and a souvenir from a 1959-1960 exhibition on Bayard in Essen, Germany. At the top left corner of pages, an early inventory system notes the page number, the number of images on the page, and total number of photographs in the album up to that point. Numbers under each photograph represent a second system. At the bottom of the pages, Getty Museum staff and Crane each assigned an accession number to identify the album within their collections. Note that Getty numbers begin with “84.XO.968.” and Crane numbers with “A58.”.

With each change of hands, the album has adopted new meanings. It started as an artist’s notebook and portfolio. Upon Bayard’s death it became a family memento and then a symbol of a commune’s pride. Later in the twentieth century, it shifted from an antiquarian book dealer’s curious commodity to a collector’s treasure. Today it is a museum object valued for what it tells us about processes, subject matter, and sophisticated lines of communication between photographers during the earliest years of photography.

Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs, 2024

For more information see:

~ Hellman, Karen and Carolyn Peter, eds. Hippolyte Bayard and the Invention of Photography. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2024.

~ Peter, Carolyn. “The Many Lives of the Getty Bayard Album.” Getty Research Journal 15 (2022): 67-86.

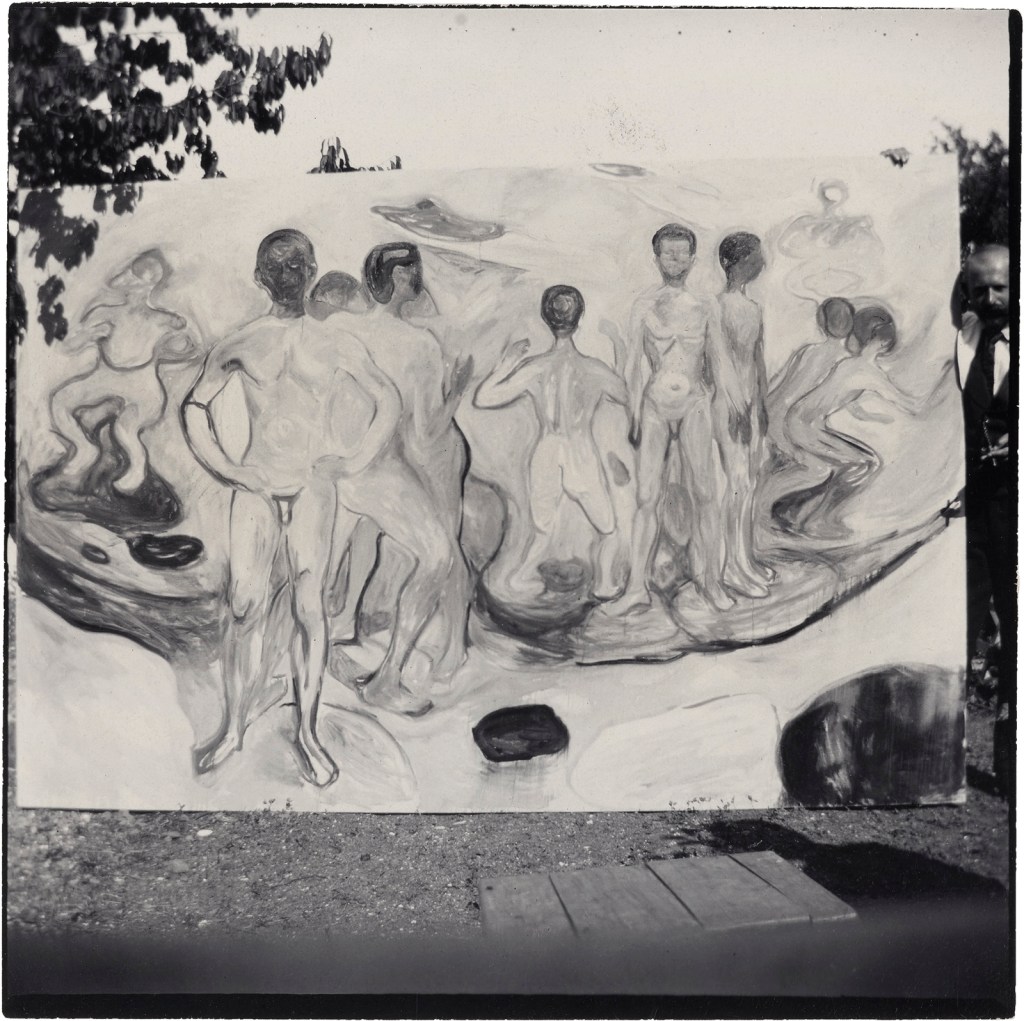

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker

Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] showing at top left Hippolyte Bayard’s [Three Feathers] About 1842-1843

1839-1855

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Three Feathers]

About 1842-1843

Part of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] 1839-1855

Cyanotype

13.8 x 11.1cm (5 7/16 x 4 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

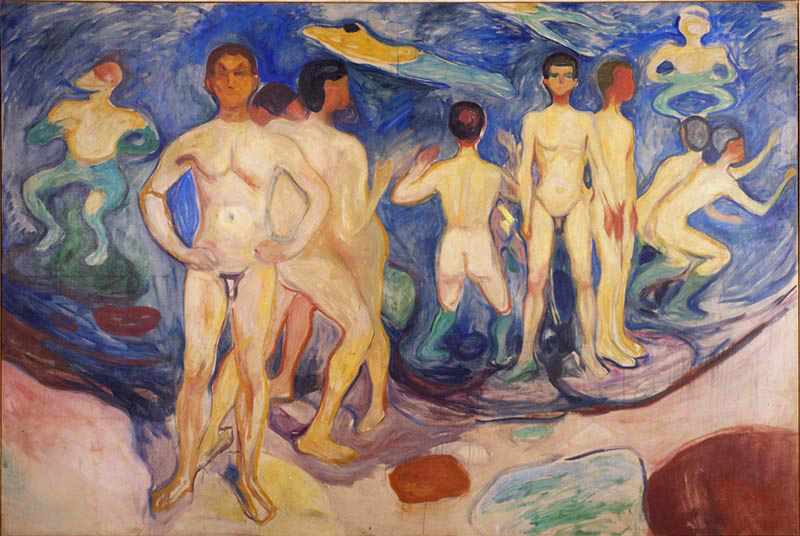

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker

Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] showing at top right, Hippolyte Bayard’s Arrangement of Flowers about 1839-1843

1839-1855

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

Arrangement of Flowers

About 1839-1843

Part of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] 1839-1855

Salted paper print

17.5 × 21.3cm (6 7/8 × 8 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

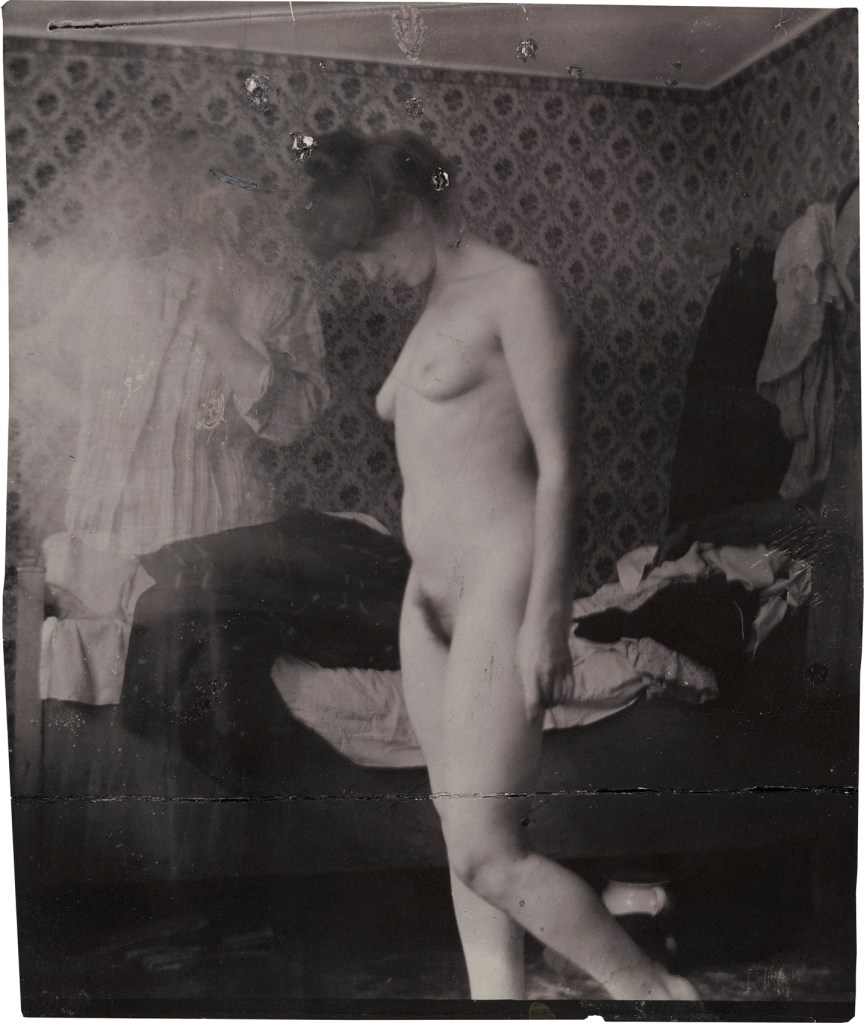

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker

Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] showing at bottom right, Hippolyte Bayard’s [Portrait of a Man] 1843-1845

1839-1855

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

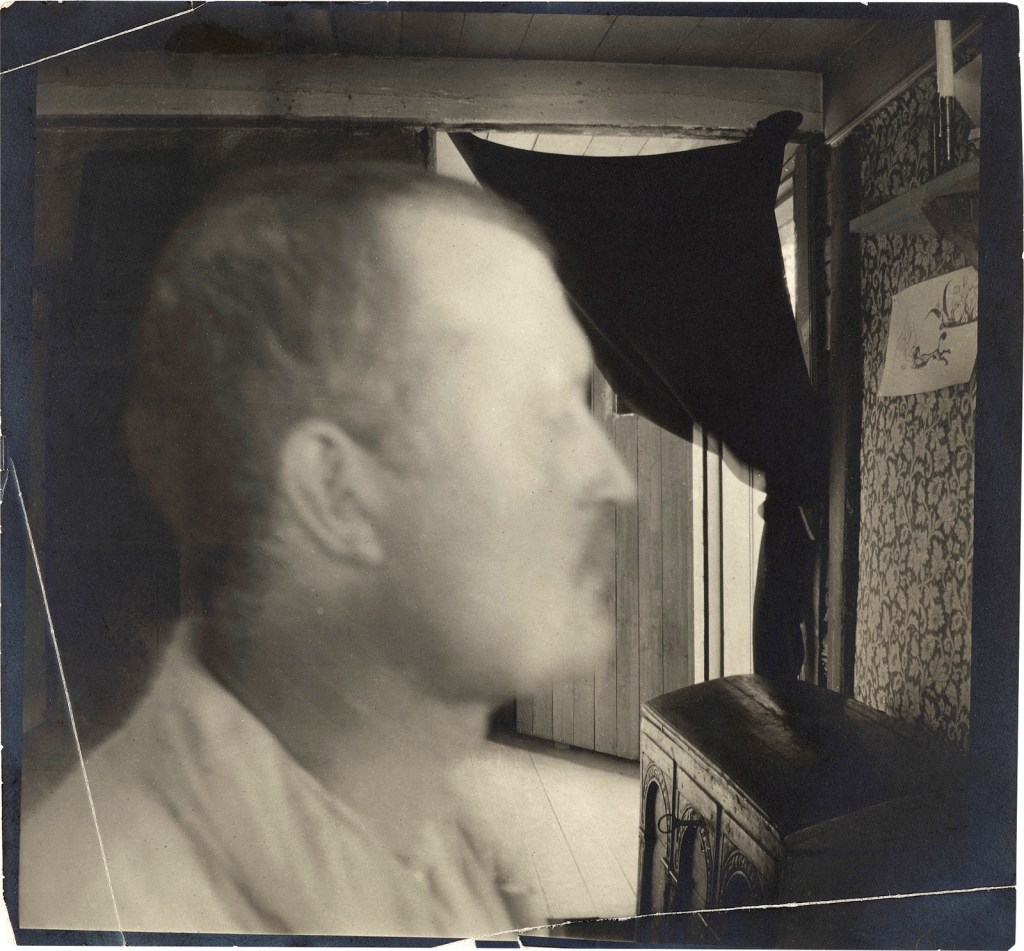

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Portrait of a Man]

1843-1845

Part of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] 1839-1855

Salted paper print

Image: 15.3 × 11.6 cm (6 × 4 9/16 in.)

Sheet: 15.7 × 12 cm (6 3/16 × 4 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

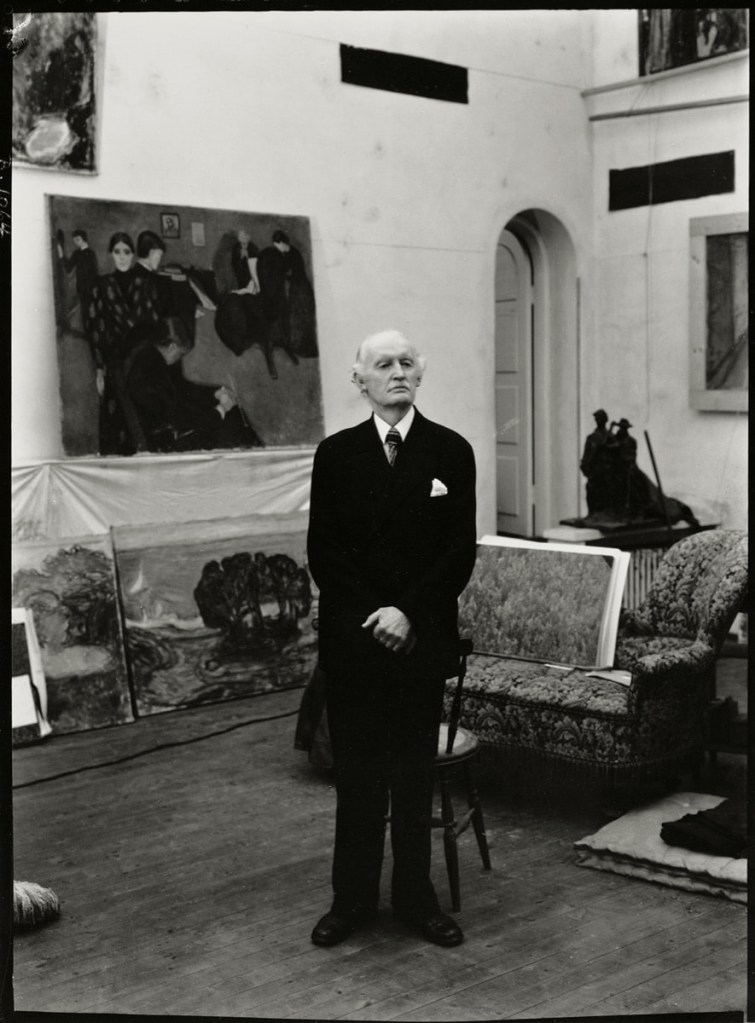

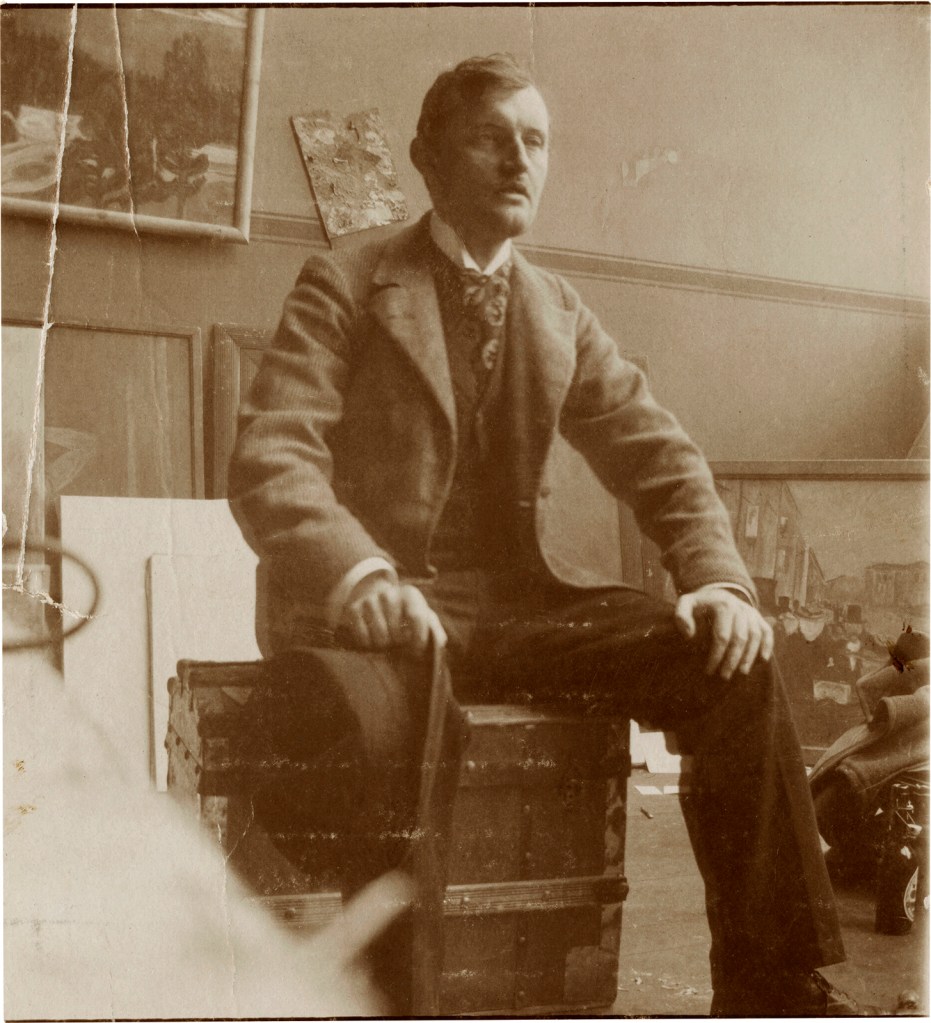

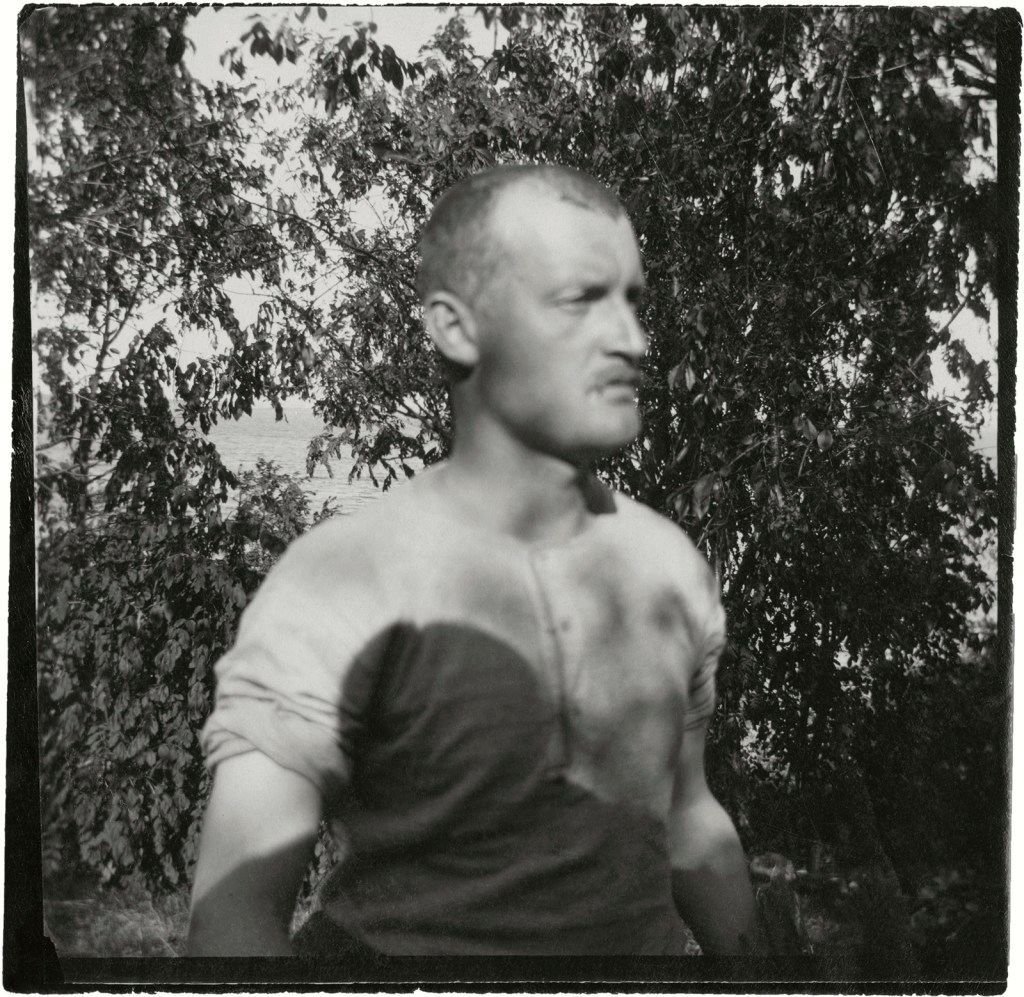

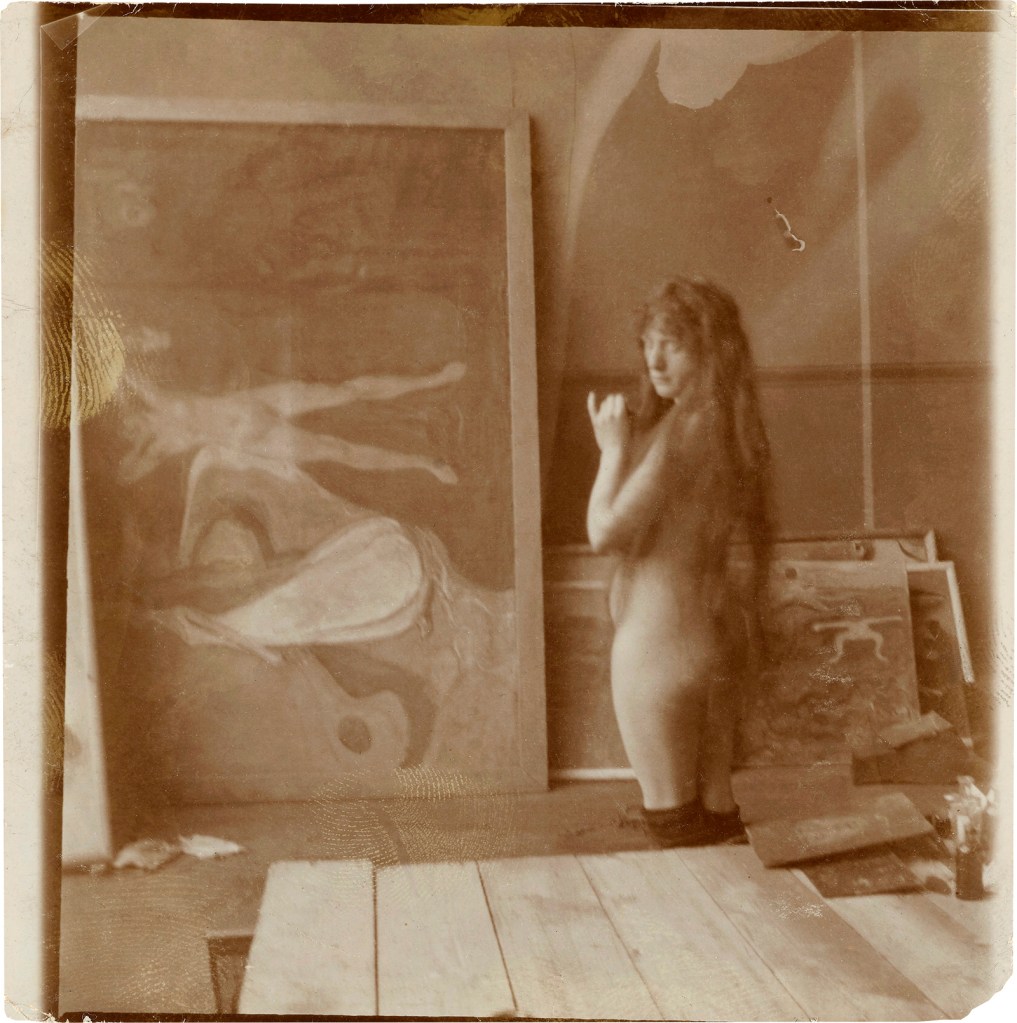

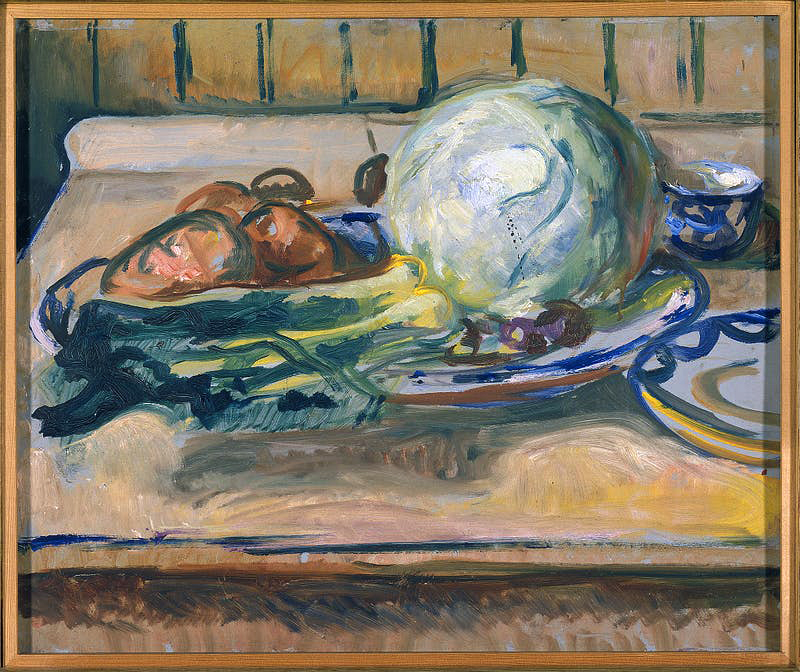

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[In Bayard’s Studio]

About 1845

Part of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] 1839-1855

Salted paper print

23.5 × 17.5cm (9 1/4 × 6 7/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard is one of the earliest photographers to explore self-portraiture using a camera. The Getty Museum’s collection includes seven of Bayard’s self-portraits (see 84.XO.968.1, 84.XO.968.166, 84.XO.968.20).* While Bayard is not present in this image, it too can be considered a self-portrait of sorts as it offers the viewer a window onto his artistic world. The seemingly casual composition shows a make-shift photographic studio with wood doors leaning up against a brick wall to form the principal back wall. The floor is rough; it isn’t clear whether it is made of tile, wood, or simply dirt. Bayard featured the tools of his trade – glass bottles filled with chemicals, a beaker, a funnel, a dark canvas backdrop, and a light curtain or coverlet as well as some of his favourite subjects – three plaster casts and a porcelain vase. The Société française de photographie (SFP) collection in Paris has two versions of this image; one of them is hand-coloured. The overpainting with watercolour heightens the various patterns and adds colours that the photographic process was unable to capture.

Many of these same props can be found in a number of Bayard’s photographs. The vase with its elaborate floral design as well as the small figure with arms extended, the coverlet, backdrop, and bench are integral parts of Bayard’s most famous self-portrait, Le Noyé [The Drowned Man], now housed at the SFP.

*Four of the Getty’s Bayard self-portraits are part of a portfolio printed in 1965 by M. Gassmann and Son from Bayard’s original negatives that are housed in the SFP collection. (See: 84.XO.1166.1, 84.XO.1166.2, 84.XO.1166.8, and 84.XO.1166.25).

Carolyn Peter. J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photographs

2019

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker

Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] showing at bottom right, Hippolyte Bayard’s [Galerie de la Madeleine with Scaffolding, Place de la Madeleine] 1843

1839-1855

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Galerie de la Madeleine with Scaffolding, Place de la Madeleine]

1843

Part of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] 1839-1855

Salted paper print

Image: 16.5 × 22cm (6 1/2 × 8 11/16 in.)

Sheet: 16.8 × 22.3cm (6 5/8 × 8 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker

Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] showing at top right, Hippolyte Bayard’s [Rue des Batignolles] about 1845

1839-1855

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Rue des Batignolles]

About 1845

Part of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] 1839-1855

Salted paper print

15.4 x 11 cm (6 1/16 x 4 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Bitch in profile]

About 1865

Part of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] 1839-1855

Albumen silver print

Mount: 10 x 6.1cm (3 15/16 x 2 3/8 in.)

J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

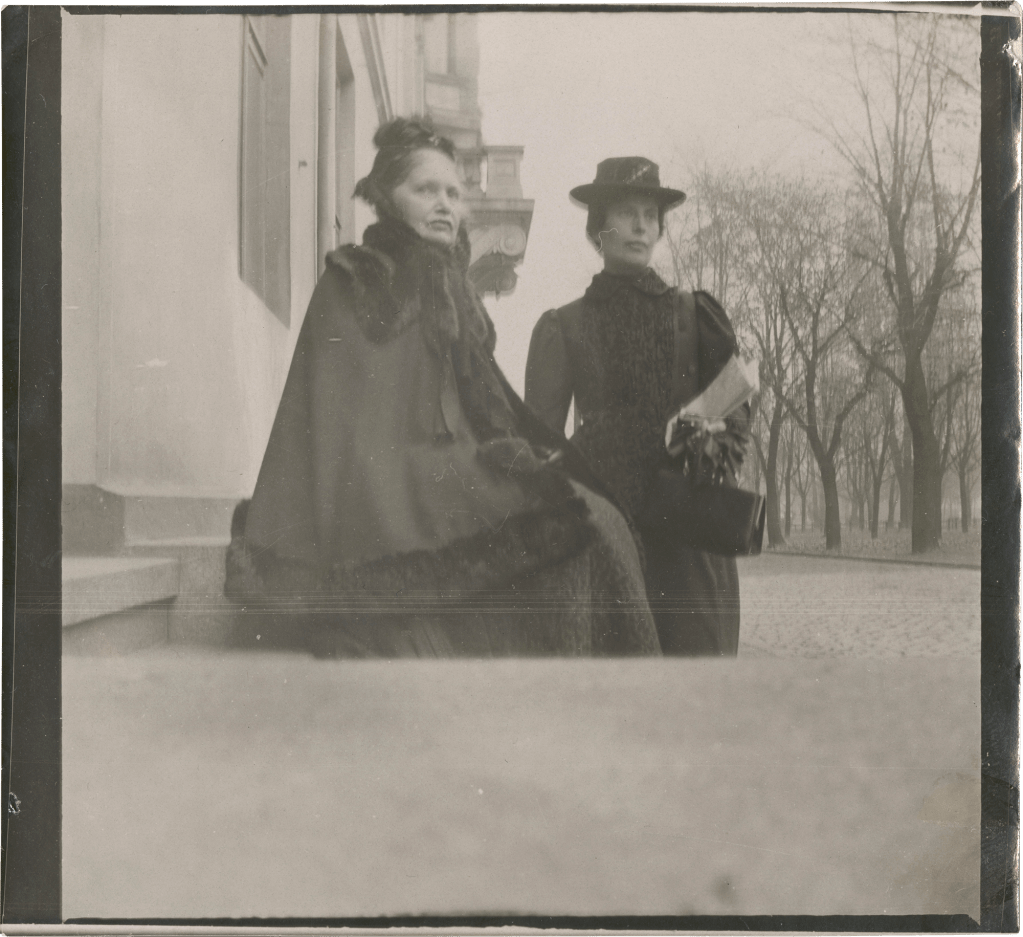

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Unidentified woman standing, leaning against a credenza]

About 1861

Albumen silver print

Mount: 10.4 x 6.1 cm (4 1/8 * 2 3/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker

Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”]

1839-1855

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

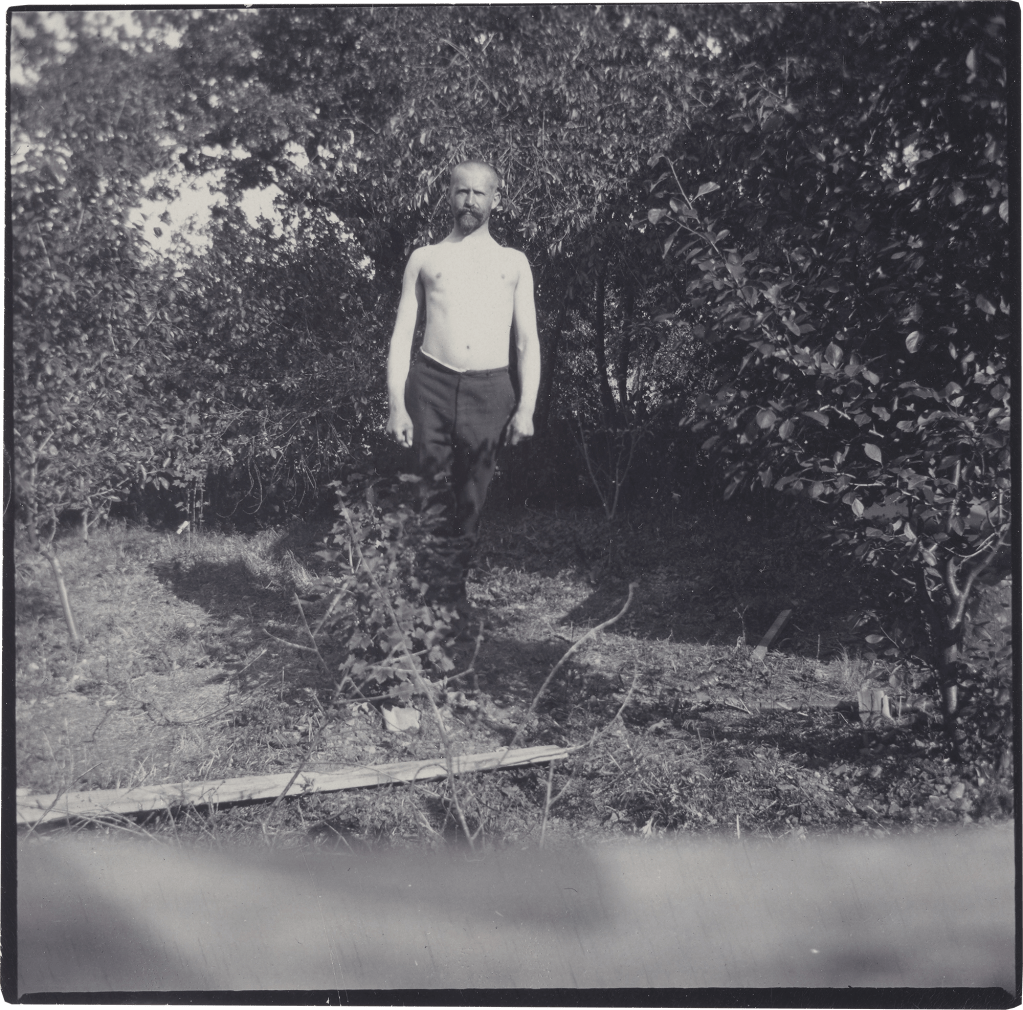

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Two Men and a Girl in a Garden]

About 1847

Part of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The “Bayard Album”] 1839-1855

Albumenised salted paper print

12.9 x 15.6cm (5 1/16 x 6 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Hippolyte Bayard

Frenchman Hippolyte Bayard was one of the earliest experimenters in photography, though few will recognise his name today. While working as a civil servant in the Ministry of Finance in the late 1830s and early 1840s, he devoted much of his free time to inventing processes that captured and fixed images from nature on paper using a basic camera, chemicals, and light. The announcement of the inventions of his fellow countryman Louis-Jacques Mandé Daguerre’s daguerreotype on January 7, 1839, and Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot’s photogenic drawing soon after greatly diminished opportunities for recognition of Bayard’s contributions. He was most likely persuaded by François Arago, the head of the French Academy of Sciences, to keep quiet about his own distinct process until after the announcement of Daguerre’s process and subsequent celebration in August of 1839.

Bayard nonetheless continued his investigations and submitted letters detailing three photographic recipes to the Academy of Sciences. Though he exhibited examples of his work in what has been recognised as the first public exhibition of photography in July 1839 and presented his direct positive process at the Academy of Fine Arts in November of 1839, where it was lauded as an important tool for artists, he remained in the shadows of Daguerre and Talbot.

Bayard is best known today for his 1840 self-portrait as a drowned man, to which he added text protesting the lack of recognition for his invention. The humorous, yet biting text read:

The corpse of the gentleman you see here…. is that of Monsieur Bayard, inventor of the process that you have just seen…. As far as I know this ingenious and indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with perfecting his discovery…. The Government, who gave much to Monsieur Daguerre, has said it can do nothing for Monsieur Bayard, and the poor wretch has drowned himself. Oh! The precariousness of human affairs! …

In reality, of the three inventors, it was Bayard who actively continued to photograph the longest. He was a founding member in the 1850s of the Société héliographique and its successor, the Société française de photographie. He kept up with the latest developments in the world of photography and integrated new processes into his practice. He was one of only five photographers selected to be part of the Missions héliographiques in 1851, charged with the task of documenting France’s historic architecture for the Commission des Monuments historiques. He exhibited regularly in the universal expositions and, in the 1860s after his retirement from the Ministry of Finance, opened a photographic portrait studio in Paris with Charles Albert d’Arnoux, known as Bertall (1820-1882). During his lifetime, Bayard was described as the “Grandfather of Photography” by several commentators. The Légion d’honneur (still considered today the highest order of military and civil decoration in France) awarded him the first level of merit – Chevalier – in 1863. In the late 1860s he left Paris and moved to Nemours near his lifelong friend, the actor and painter Edmond Geffroy (1804-1895). Bayard died there in 1887.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

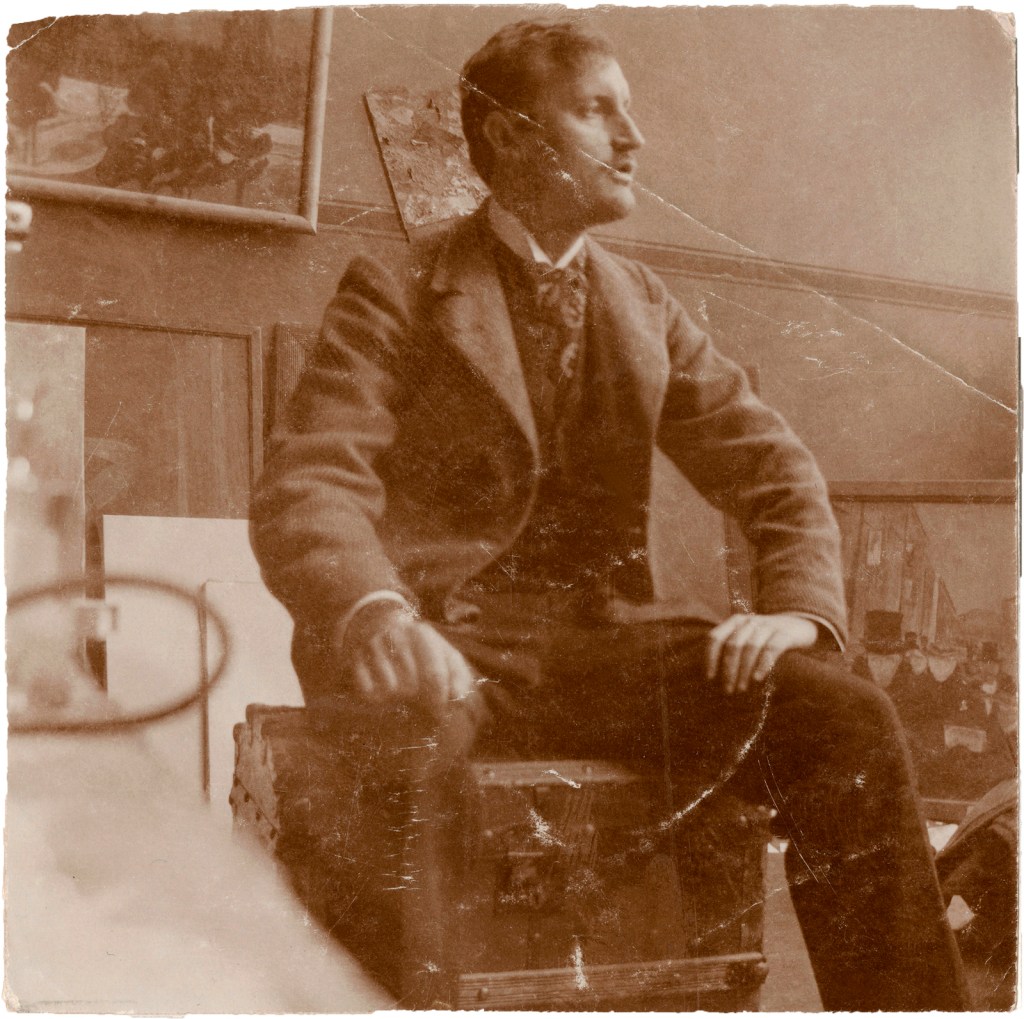

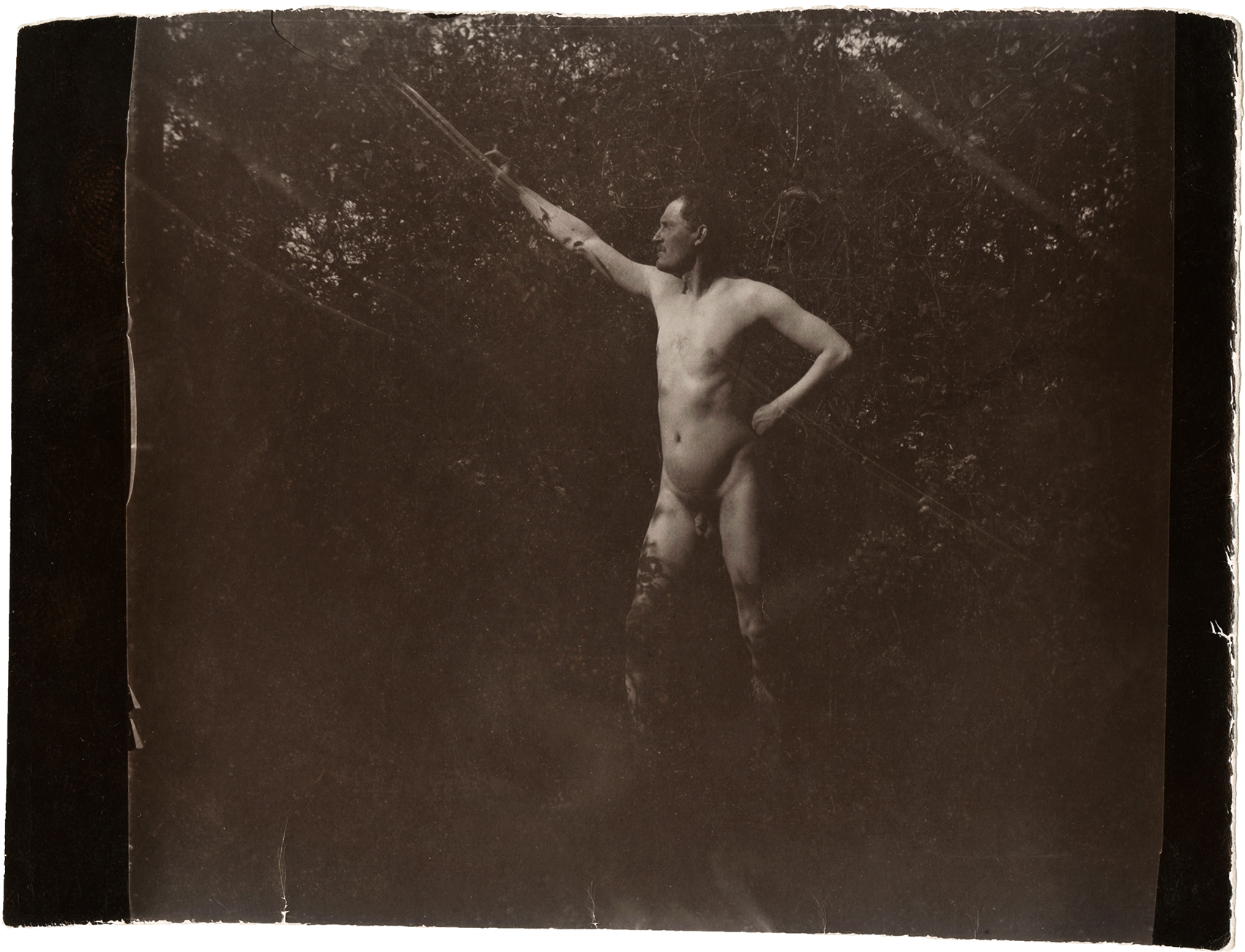

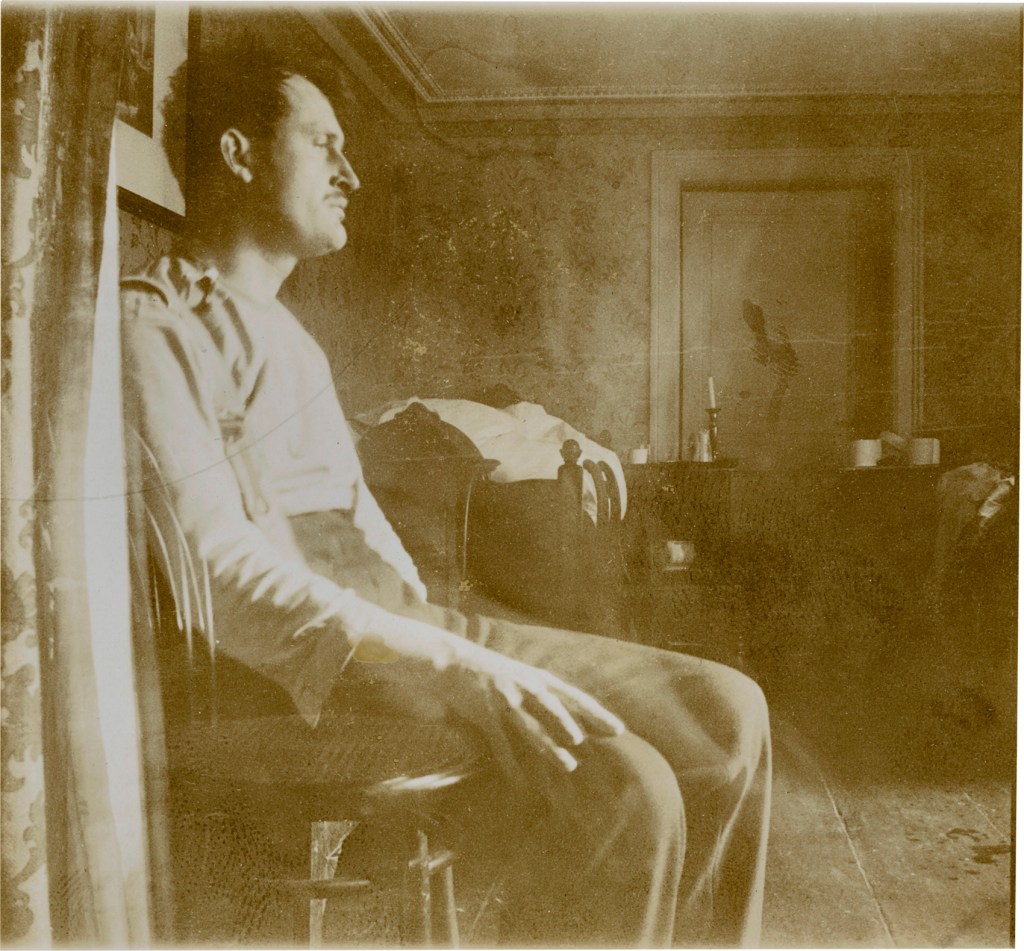

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Self-Portrait in the Garden]

1847

Salted paper print

Image: 16.5 × 12.3cm (6 1/2 × 4 13/16 in.)

Sheet: 17.1 × 12.5cm (6 3/4 × 4 15/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

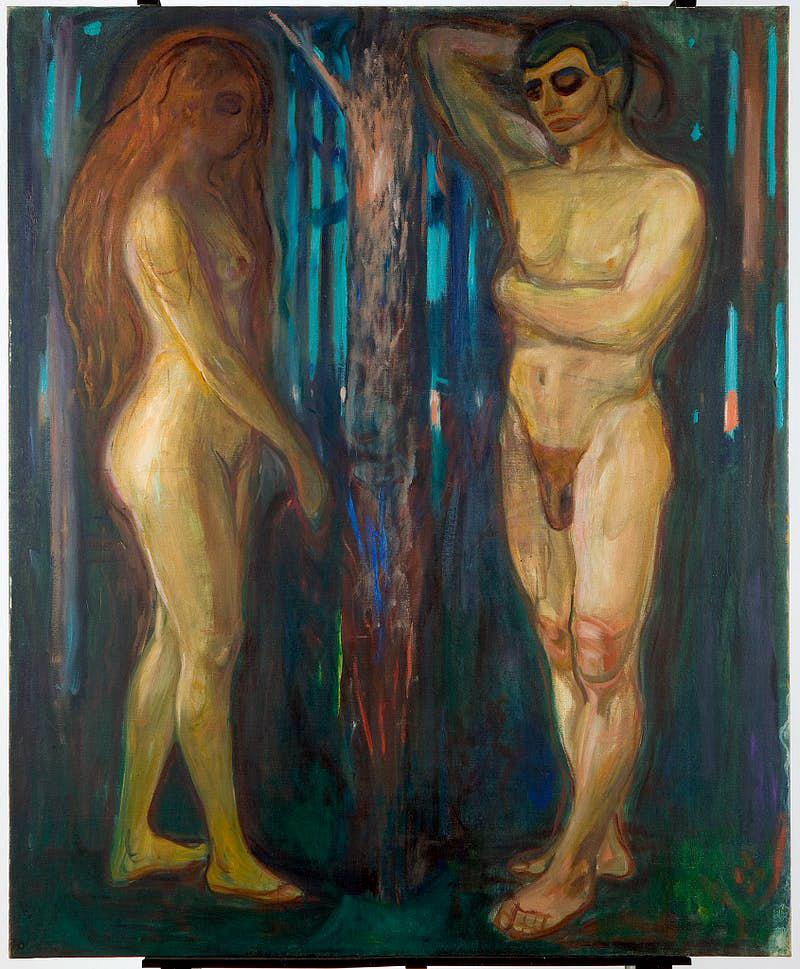

By October 1840, a little over a year after several competing photographic processes had been made public, Hippolyte Bayard began staging elaborate self-portraits in his garden and other locations. His best known, Le Noyé [The Drowned Man], was made on October 18, 1840 (three variants are now part of the collection of the Société française de photographie in Paris).

The Getty Museum’s collection includes six other self-portraits by Bayard in addition to this 1847 Self-portrait in the Garden (See: 84.XO.968.1, 84.XO.968.166).* In five of the seven self-portraits, he placed himself in garden settings. This was, in part, a practical decision since natural light was required to make photographs at the time. However, his choice of setting also reflects his passion for plants. He came from a family of gardeners – his maternal grandfather worked in the extensive grounds of the abbey in Breteuil, the village where Bayard grew up. His father, a justice of the peace, was a passionate amateur gardener who grew peaches in an orchard attached to the family home. The garden(s) featured in Bayard’s self-portraits may indeed be part of the family property in Breteuil or his own home in Batignolles – an area that was just on the outskirts of Paris.

The setting becomes an integral aspect of these portraits; Bayard, the man, merges with his environment. In this particular image, he is surrounded by vegetation and is seated in a wooden chair whose arms and legs resemble vine branches. The lower portion of his legs merges into the darkened lower foreground as if he too is rooted in the earth and has sprouted from it. He shares the foreground with a tall leafy plant that bursts into blossoms at the top. The artist’s choice of clothing, including his cravat, brimmed cap, as well as his direct gaze, all combine to convey a sense of confidence.

Another image found mounted on a separate page in the same album in which this one appears offers a slightly more distant view of almost all the same elements. Bayard is no longer part of the composition, which instead features a watering can and an extra pot (See 84.XO.968.85). Perhaps this photograph was a study in preparation for this self-portrait.

*Four of the Getty’s Bayard self-portraits are part of a portfolio printed in 1965 by M. Gassmann and Son from Bayard’s original negatives that are housed in the SFP collection. (See: 84.XO.1166.1, 84.XO.1166.2, 84.XO.1166.8, and 84.XO.1166.25).

Carolyn Peter, J. Paul Getty Museum, Department of Photograph

2019

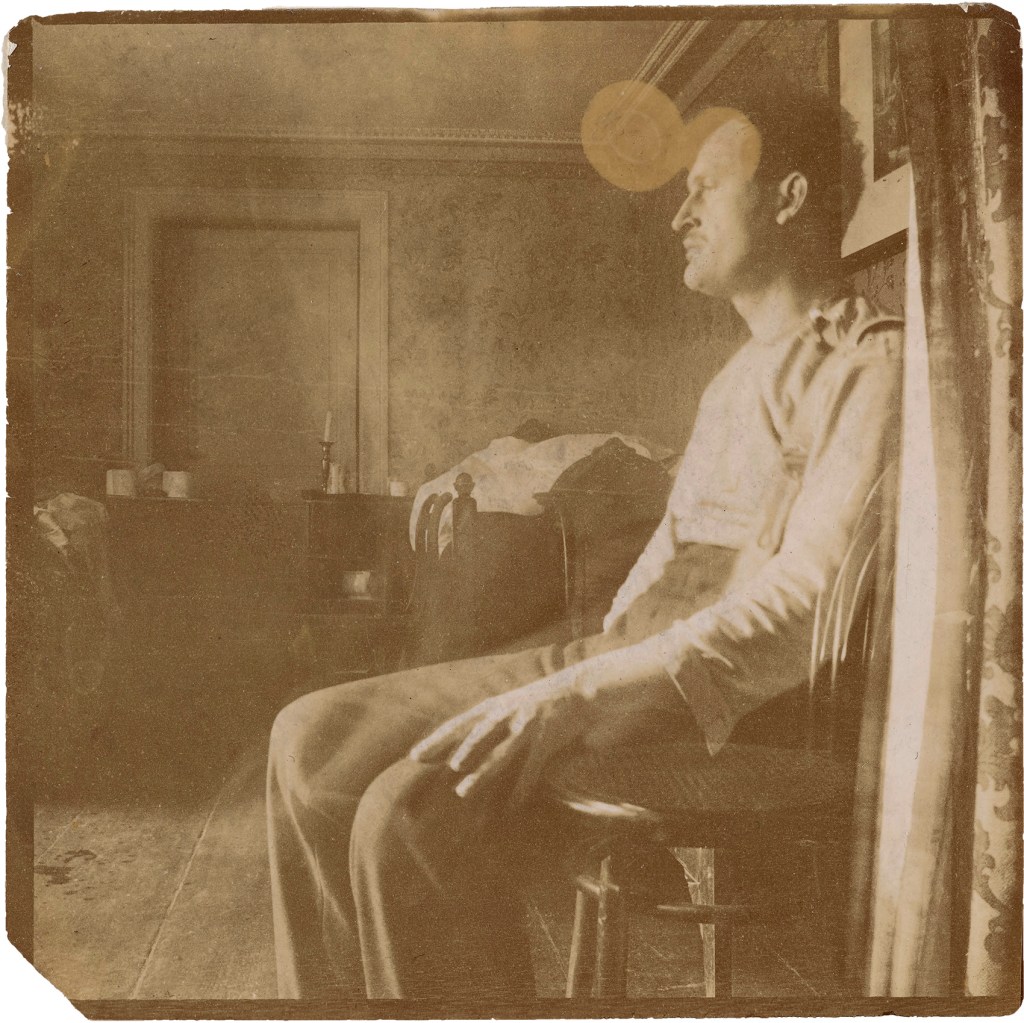

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Self-Portrait in the Garden]

June 1845

Hand-coloured

Salted paper print

12 1/4 × 9 13/16 in.

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

The 19th-Century Selfie Pioneer

Before Instagram influencers, there was Hippolyte Bayard

More than 160 years before smartphones and selfie sticks allowed even the most inexperienced shutterbug to snap a photo of themselves, Hippolyte Bayard was turning his camera on himself.

The year was 1840. Several competing photographic processes had just been made public for the first time the year before, effectively introducing the medium of photography to the world. Bayard, a bureaucrat who worked at the Ministry of Finance in Paris and took pictures on weekends or his lunch hour, was one of the first photographers to practice the art of the self-portrait. Examples of these are on view in the new Getty Center exhibition Hippolyte Bayard: A Persistent Pioneer.

With himself as the subject, Bayard could experiment with new photographic processes, set a scene, and pose in front of the camera, creating images that represented his hobbies, frustrations, and achievements. Sound familiar?

“The earliest photographers wanted to capture people in photographs. Bayard was one of the first to actually succeed,” says Carolyn Peter, the exhibition’s co-curator. He also demonstrated that photography was a new art form. “The public was so taken by the realistic depictions of the world in photography, but he was saying that you can also make things up. You can stage things.”

Bayard in the Garden

Self-portraits were an appealing solution in those early days of photography largely because taking a picture required a long, labor-intensive process, explains Peter. Photographers had to set their cameras in front of their (motionless) subjects for anywhere between 20 minutes and three hours – a daunting ask for any human being – to expose the sensitised surface (metal, paper, or glass) to enough light to create the image.

“He probably didn’t want to subject others to this endurance test, but he still wanted to try and work on his photography techniques. Gradually, the amount of time it took to make a photo shortened, maybe down to around 10 minutes, and finally down to seconds,” Peter said.

In a series of self-portraits from the 1840s, Bayard posed himself in his or his family’s gardens, among plants and tools, emphasising his passion for horticulture. The outdoor setting was a necessity as it offered plenty of natural light. He adopted several different configurations of items and positions in each portrait. Notice how in one image (above left) he hid his feet behind greenery, as if he were planted in the earth.

“Today artists, along with the rest of us, still try a lot of different positions and poses with slight variations when we are making self-portraits,” Peter says.

Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887)

[Self-Portrait in the Garden]

About 1845-1849

Salted paper print

Image: 15.9 × 12.7 cm (6 1/4 × 5 in.)

Sheet: 16.3 × 13.1 cm (6 7/16 × 5 3/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Public domain

Bayard as Dramatist

Perhaps Bayard’s best-known photo is his Drowned Man (1840), in which he slumps over, partially covered by a sheet, eyes closed, as if he had perished. Bayard created three versions of the image, changing the pose and props in each one, and eventually added this over-the-top lament to the back of the final version:

“The corpse of the gentleman that you see here… is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process you have just seen…. To my knowledge, for about three years this ingenious and indefatigable researcher has been working to perfect his invention…. The Government, which has given so much to M. Daguerre, said it could do nothing for M. Bayard, and the unfortunate man drowned himself. Oh! The precariousness of human affairs!”

Clearly, Bayard had a few frustrations about his position in the photography world and about how little respect he felt he had been given in comparison to fellow photographer Louis Daguerre. This self-portrait allowed him to express his woes in a humorous and, yes, dramatic way, perhaps inspired by his connections to the theater.

“One of his very best friends from childhood on was Edmond Geffroy, a famous actor, so Bayard hung out with actors and theater people as well as fine artists and writers,” Peter says. “He had this connection to theatricality and theater. He attended a lot of plays. So I think that influenced him.”

A Special Effects Pioneer

In the 1860s, Bayard opened a portrait studio where customers could pay to have their pictures taken. Exposure times had been dramatically reduced, making it significantly easier for ordinary folks to sit for photographs. Bayard continued to experiment, using himself as a subject. Here he combined two negatives to make it look as though he is having a conversation with himself (or an imaginary identical twin?). This is 100 years before The Parent Trap was released!

“He’s just got this sense of humour and this desire to keep playing around,” says Peter.

A Self-Portrait of Pride

Bayard might have felt profoundly under acknowledged for his work in the 1840s, but it turns out he just needed to wait a little to get his due. In 1863 he was awarded the cross of the French Legion of Honor, a prestigious award bestowed in recognition of his contributions to photography. He took the portrait above while wearing the badge, showing off what must have been one of his proudest achievements. Bayard retired from photography soon after.

Bayard’s selfies are now more than 160 years old, but selfie-takers of today seem to be (unconsciously) following the same principles Bayard experimented with. He was one of the first to show that photography could represent not just the literal world but also how you wanted to present yourself. While selfies may appear to be a new phenomenon spawned by the reverse-camera button on smartphones, selfie aficionados should pay proper homage to Bayard for pioneering this art form.

“Today, selfies often include humour. Photographers invest a lot of strategic thought into how they want to present themselves. Selfies are performative and create something that isn’t fully realistic. Bayard was also conscious of the power of photography to visually imagine other worlds and invent different versions of himself.”

Erin Migdol. “The 19th-Century Selfie Pioneer,” on the J. Paul Getty Museum website Apr 09, 2024 [Online] Cited 12/04/2024

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Cover of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"]' 1839-1855 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Cover of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"]' 1839-1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/the-bayard-album-cover.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Title page of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"] with Hippolyte Bayard 's [Self-Portrait in the Garden] June 1845' 1839-1855 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Title page of Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"] with Hippolyte Bayard 's [Self-Portrait in the Garden] June 1845' 1839-1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/title-page-of-the-bayard-album-with-bayards-self-portrait-in-the-garden.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"]' 1839-1855 showing at top left Hippolyte Bayard's '[Three Feathers]' about 1842-1843 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"]' 1839-1855 showing at top left Hippolyte Bayard's '[Three Feathers]' about 1842-1843](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-album-a.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Three Feathers]' About 1842-1843 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Three Feathers]' About 1842-1843](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/gm_10846601_web.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"]' 1839-1855 showing at top right, Hippolyte Bayard's 'Arrangement of Flowers' about 1839-1843 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"]' 1839-1855 showing at top right, Hippolyte Bayard's 'Arrangement of Flowers' about 1839-1843](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-album-b.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"] showing at bottom right, Hippolyte Bayard's [Portrait of a Man] 1843-1845' 1839-1855 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"] showing at bottom right, Hippolyte Bayard's [Portrait of a Man] 1843-1845' 1839-1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-album-d.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Portrait of a Man]' 1843-1845 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Portrait of a Man]' 1843-1845](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-portrait-of-a-man.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[In Bayard's Studio]' About 1845 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[In Bayard's Studio]' About 1845](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-in-bayards-studio.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"] showing at bottom right, Hippolyte Bayard's [Galerie de la Madeleine with Scaffolding, Place de la Madeleine] 1843' 1839-1855 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"] showing at bottom right, Hippolyte Bayard's [Galerie de la Madeleine with Scaffolding, Place de la Madeleine] 1843' 1839-1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-album-e.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Galerie de la Madeleine with Scaffolding, Place de la Madeleine]' 1843 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Galerie de la Madeleine with Scaffolding, Place de la Madeleine]' 1843](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-galerie-de-la-madeleine-with-scaffolding.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"] showing at top right, Hippolyte Bayard's [Rue des Batignolles] about 1845' 1839-1855 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"] showing at top right, Hippolyte Bayard's [Rue des Batignolles] about 1845' 1839-1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-album-f.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Rue des Batignolles]' about 1845 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Rue des Batignolles]' about 1845](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/gm_04476001_web.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Bitch in profile]' about 1865 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Bitch in profile]' about 1865](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/gm_09531001_web.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Unidentified woman standing, leaning against a credenza]' about 1861 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Unidentified woman standing, leaning against a credenza]' about 1861](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/gm_09860801_web.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"]' 1839-1855 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) William Henry Fox Talbot (English, 1800-1877) Samuel Buckle (British, 1808-1860) Nicolaas Henneman (British, 1813-1893) Reverend Calvert Jones (British, 1804-1877) David Kinnebrook (English, 1819-1865) M.H. Nevil Story-Maskelyne (British, 1823-1911) Unknown maker. 'Dessins photographiques sur Papier. Recueil No. 2. [The "Bayard Album"]' 1839-1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-album-c.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Two Men and a Girl in a Garden]' About 1847 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Two Men and a Girl in a Garden]' About 1847](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-two-men-and-a-girl-in-a-garden.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Self-Portrait in the Garden]' 1847 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Self-Portrait in the Garden]' 1847](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-self-portrait-in-the-garden1.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Self-Portrait in the Garden]' June 1845 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Self-Portrait in the Garden]' June 1845](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-self-portrait-in-the-garden-june-1845.jpg)

![Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Self-Portrait in the Garden]' About 1845-1849 Hippolyte Bayard (French, 1801-1887) '[Self-Portrait in the Garden]' About 1845-1849](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/bayard-self-portrait-in-the-garden.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.