Exhibition dates: 18th June to 15th September 2024

Curators: Toya Viudes de Velasco and Miguel Lusarreta

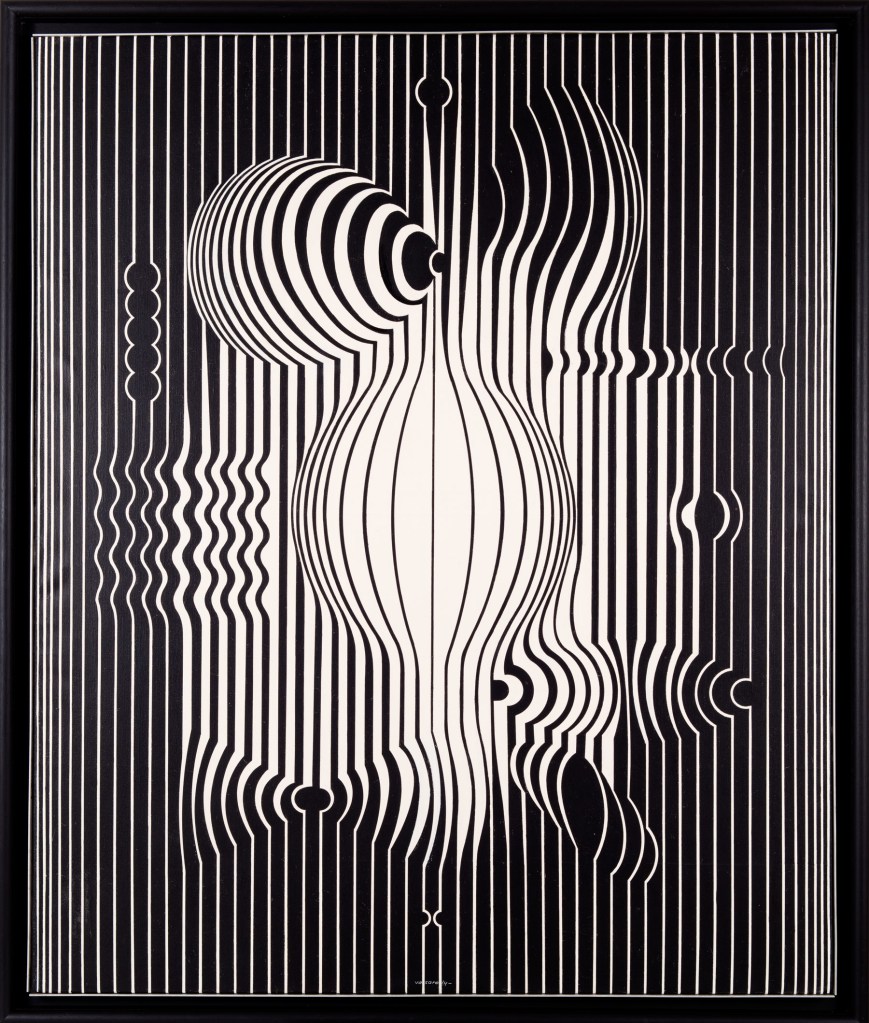

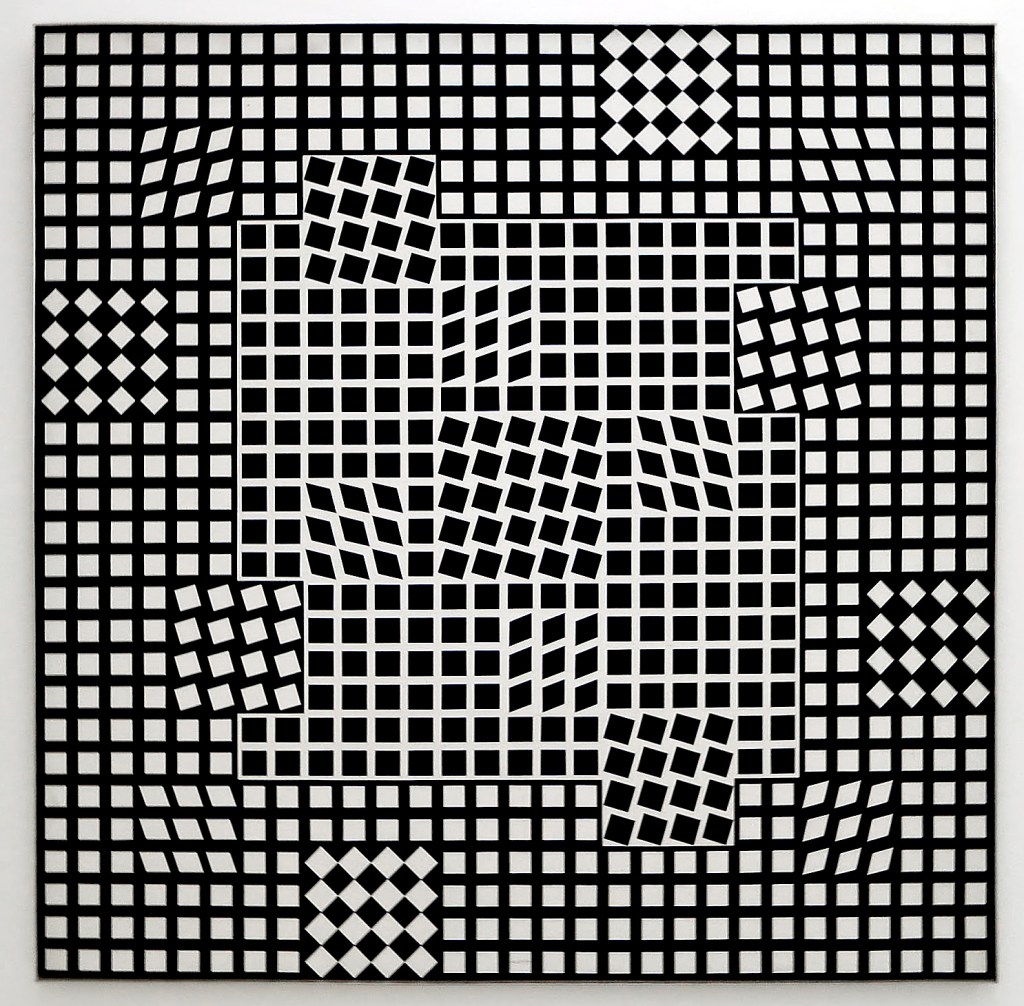

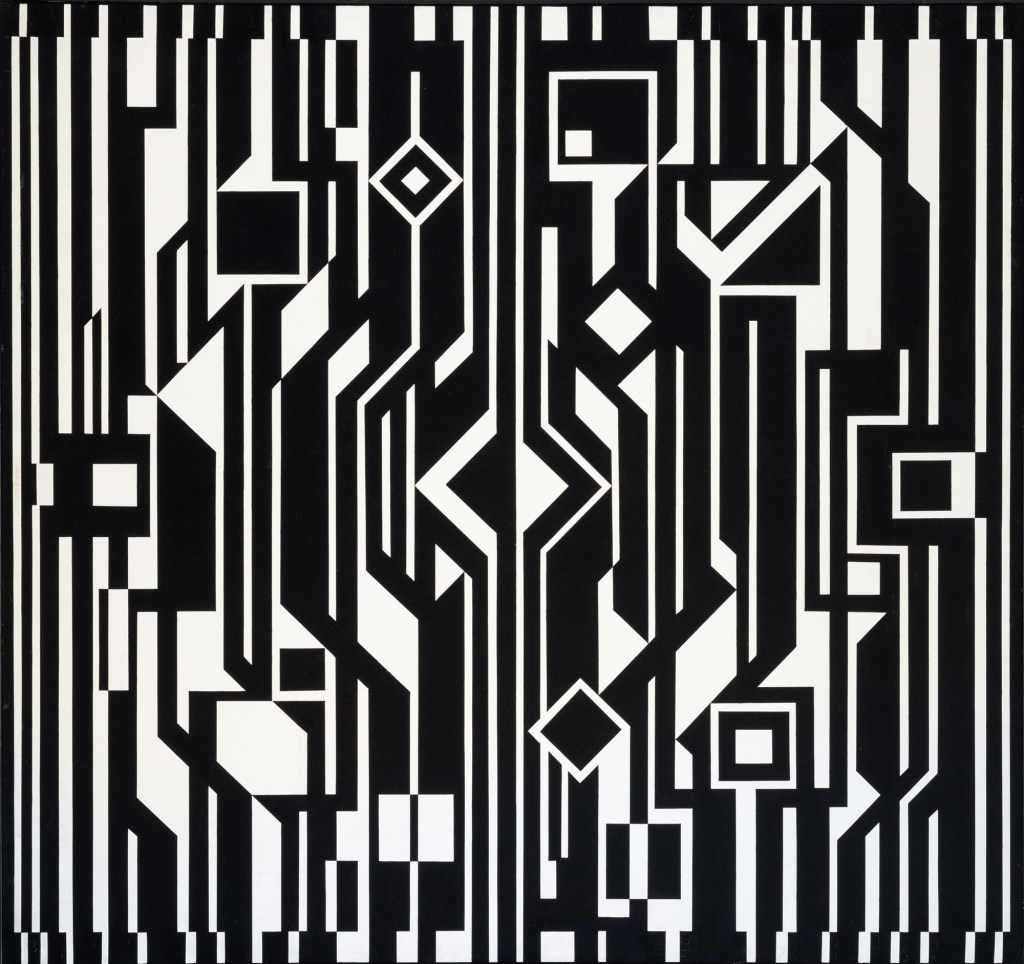

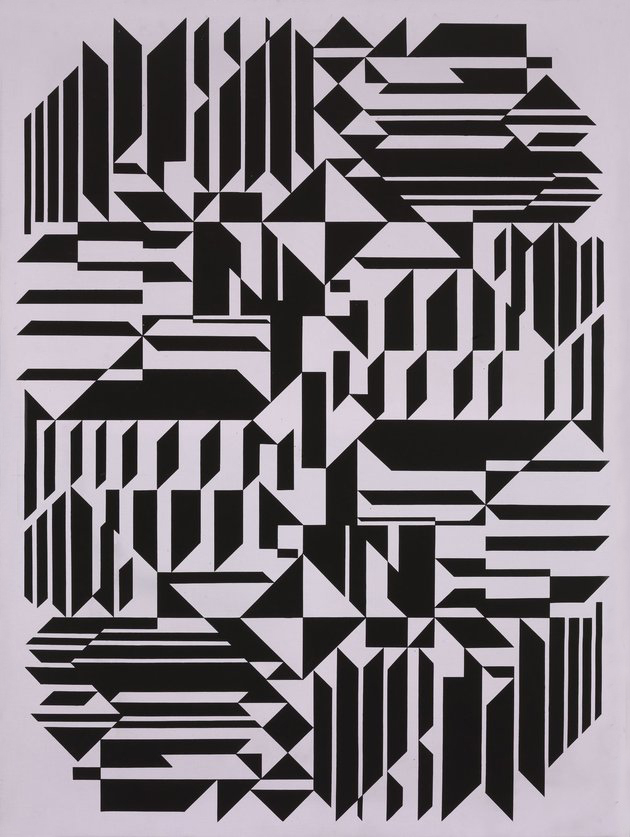

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Adam and Eve (Adán y Eva)

1932

Oil on canvas

109 x 134cm

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

Photo credit: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía Photographic Archive

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

(hidden) in plain sight

When Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid sent me an email about this exhibition I was captivated by the beautiful paintings of Rosario de Velasco, an artist who I had never hear of before, and I decided to do a posting on the exhibition.

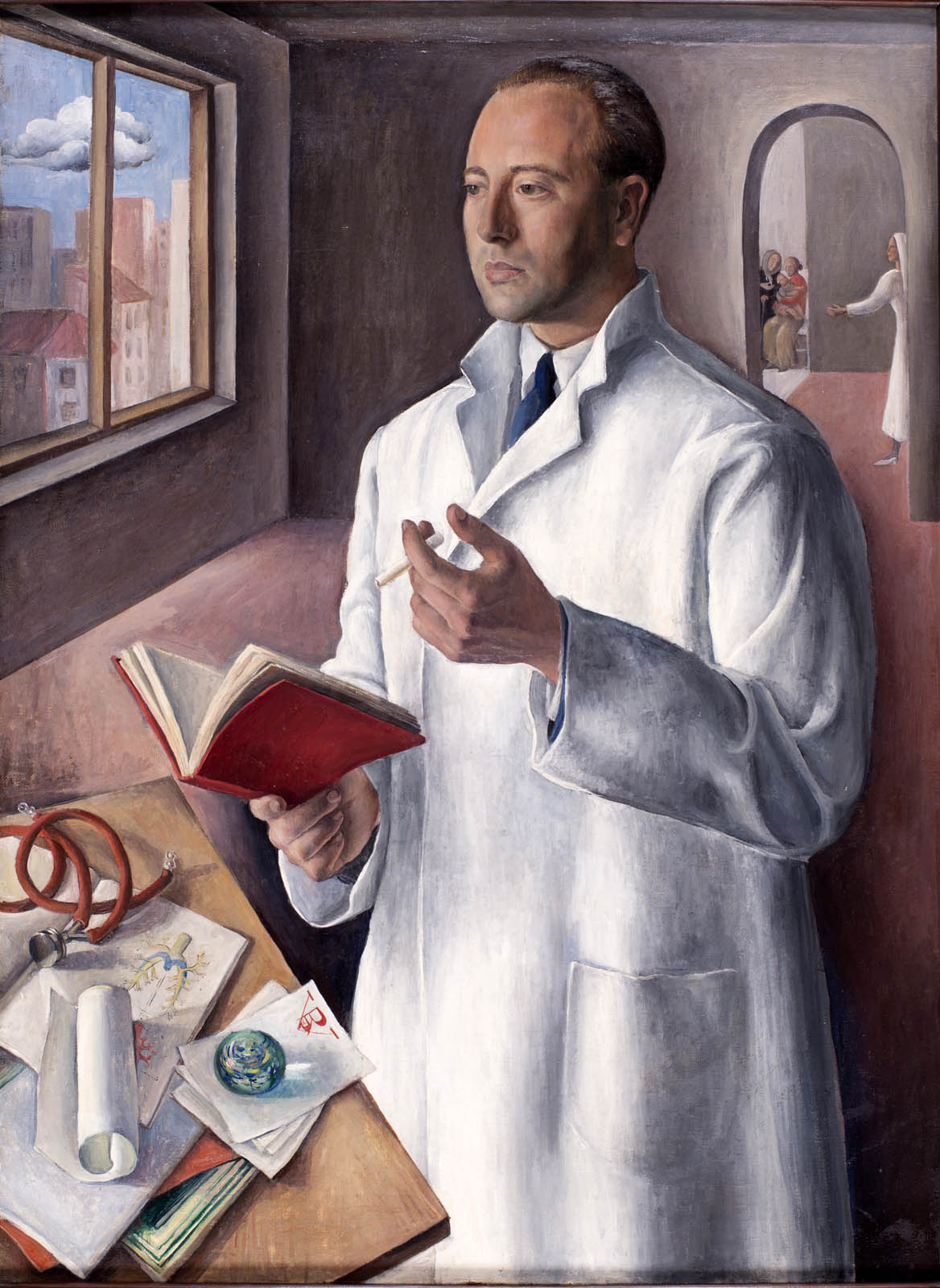

Rosario de Velasco was part of the “return to order” movement in Spain which was a style that combined tradition and modernity, associated with a revival of classicism and realistic painting. The paintings are stylish with clean lines and finely honed forms. Among other influences, they evoke Cubism in the tilting of perspective and De Chirico in the slightly twisted perspective of the architectural landscape scenes (for example, see Portrait of Doctor Luis de Velasco (Retrato del doctor Luis de Velasco) c. 1933 below) … while also incorporating magic realism (a style which presents a realistic view of the world while incorporating magical elements) in their story telling.

The press release and various commentators link de Velasco’s paintings to the Italian Novecento and German New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movements and there are visible connections to these movements in the work. De Velasco stated that Novecento was an influence on her art practice. But while there are surface similarities in style to the likes of Christian Schad, for example, I believe that de Velasco’s work is of a different order: for New Objectivity was described by art historian G.F. Hartlaub, as ‘new realism bearing a socialist flavour’. And while de Velasco’s work bears a working class flavour it is anything but socialist.

While New Objectivity mines the satirical, debauched air of decadence of the Weimar Republic, de Velasco’s paintings are a paen (perhaps even a sermon) to motherhood, heterosexuality, religiosity, utopianism and the fascist desire for a clean, lean and muscular art. Figurative stylisation and idealisation are used to evidence this desire for wholesomeness in her paintings of gypsies, peasants and working people (just as the stereotypical form of modern realist painting imposed by Stalin following his rise to power after the death of Lenin in 1924 crushed all extant art movements in Russia including the wonderful, briefly flowering Ukrainian modernist movement).

Indeed, glossed over by the press release in a paragraph or two, is the fact that de Velasco believed in the ideas of the Spanish fascists, in “the ideas of the Falange Española de las JONS and José Antonio Primo de Rivera [which] led her to collaborate with the magazine Vértice between 1937 and 1946, where she illustrated the ideology of the new regime.”1 Her art was placed at the service of propaganda and as an artist she benefitted from being on the side of the regime.

It’s a prickly question: Is her ideology complicit with her art? Can you separate the artist from the art?

And the answer is, no you can’t.

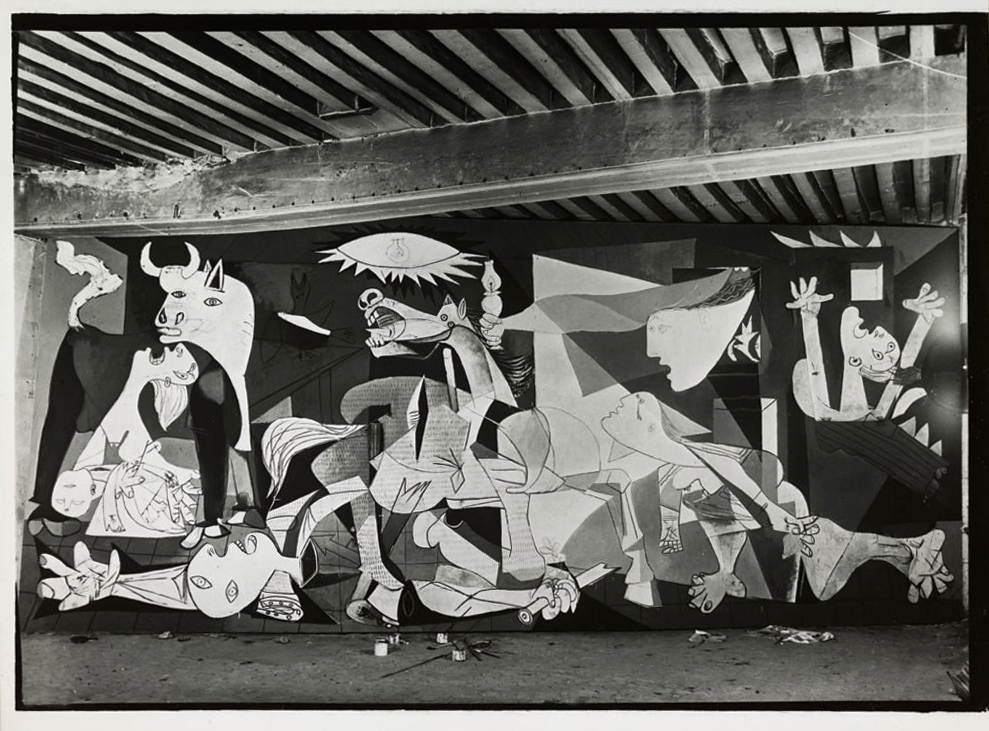

In Rosario de Velasco’s paintings the ideology slips behind the surface but it is still there. Witness the diabolical power of destruction rained down on a civilian population in Picasso’s painting Guernica (1937) – “an emotional response to war’s senseless violence ” – when compared to de Resario’s very Catholic, idealistic preternatural interpretation of a massacre in her The Massacre of the Innocents (La matanza de los inocentes) (1936, below). “She covers up with religious aura what was actually going on.”2

With the transition to democracy in Spain starting after the death of Franco in November 1975, “the exiled and forgotten republican artists were recovered, Rosario de Velasco was ignored both for her genre and for her ideology.”3 But now with her rehabilitation – noun: the action of restoring someone to former privileges or reputation after a period of disfavour – in her privilege, her special right to speak as an artist to all, we must not be blinded to the fact that de Velasco’s art is authoritarian utopian erasing social libertarian hiding dystopian destruction.

As my good friend, writer and philosopher Associate Professor James McArdle commented on Rosario de Velasco’s work: “I think we can admire the art but we must be knowing of its seduction, and be prepared to see straight through it to that layer of ideology ‘hidden in plain sight’.”4

Personally, I believe that it’s not so much hidden in plain sight, but right there in plain sight. If you are an informed, aware, sentient human being you know these things, you feel these things, and you can see these things.

There is never any excuse for a collective forgetting or cultural amnesia of the ideologies of the past for, with the rise of the far right around the world, they are returning to haunt us.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Anonymous. “La matanza de los inocentes,” on the on the Museo Belles Arts Valencia website Nd [Online] Cited 05/09/2024. Translated by Google Translate from the Spanish text

2/ Associate Professor James McArdle email to the author, 04/09/2024

3/ Anonymous. “La matanza de los inocentes,” on the on the Museo Belles Arts Valencia website Nd [Online] Cited 05/09/2024. Translated by Google Translate from the Spanish text

4/ Associate Professor James McArdle email to the author, 04/09/2024

Many thankx to the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“Rosario de Velasco is part of the “return to order” movement in Spain, parallel to the German New Objectivity and the Italian Novecento, with a style that combines tradition and modernity. The artist admired masters such as Giotto, Mantegna, Piero de la Francesca, Durero, Velázquez and Goya, but also the vanguardists, such as De Chirico, Braque or Picasso and the protagonists of that return to order in Germany and Italy that she met through of magazines and exhibitions held in the 1920s in Madrid.”

Cristina Perez. “La fuerza bíblica de Rosario de Velasco ilumina el Museo Thyssen,” (The biblical force of Rosario de Velasco illuminates the Thyssen Museum) on the rtve website 18.06.2024 [Online] Cited 14/08/2024. Translated from the Spanish by Google Translate

The return to order (French: retour à l’ordre) was a European art movement that followed the First World War, rejecting the extreme avant-garde art of the years up to 1918 and taking its inspiration from classical art instead. The movement was a reaction to the war. Cubism was partially abandoned even by its co-creator Picasso. Futurism, which had praised machinery, dynamism, violence and war, was rejected by most of its adherents. The return to order was associated with a revival of classicism and realistic painting.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Installation view of the exhibition Rosario de Velasco at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza showing in the bottom image, Velasco’s Adam and Eve (1932, above)

Installation view of the exhibition Rosario de Velasco at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza showing Velasco’s Portrait of Doctor Luis de Velasco (c. 1933, below)

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Portrait of Doctor Luis de Velasco (Retrato del doctor Luis de Velasco)

c. 1933

Oil on canvas

114 x 84cm

José A. de Velasco Collection

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

The Jeweller Karl Krall (Der Juwelier Karl Krall)

1923

Oil on canvas

Kunst- und Museumsverein im Von der Heydt-Museum Wuppertal

This painting is not in the exhibition and is used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research.

The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza is jointly organising with the Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia an exhibition on the Spanish figurative painter Rosario de Velasco (Madrid, 1904 – Barcelona, 1991).

Curated by Miguel Lusarreta and Toya Viudes de Velasco, the artist’s great-niece, the exhibition features 30 paintings from the 1920s to 1940s (the earliest and the most important from Velasco’s career) and a section on her activities as an illustrator. Alongside well known works from museum collections, such as the famous oil Adam and Eve from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, with which the artist obtained the second-prize medal for painting at the National Fine Arts Exhibition in 1932, or The Massacre of the Innocents (1936) from the Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia, there will be others on display for the first time that have remained with Velasco’s family and in private collections, some unlocated until recently and only found and identified in the past few years.

Through a selection of paintings, drawings and illustrations and employing an approach that combines general art-historical issues and also explores aesthetic, social and political aspects, the exhibition aims to rediscover and reassess the work of one of the great Spanish women artists of the first half of the 20th century.

Following its showing in Madrid the exhibition will be seen at the Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia from 7 November 2024 to 16 February 2025.

Text from the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza website

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Seamstress Asleep

c. 1930

Oil on canvas

56 × 75cm

Private collection

Photo: Jonás Bel

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Still Life with Fish (Bodegón con peces)

c. 1930

Oil on canvas

42 × 60cm

Ibáñez Museum Collection, Olula del Rio

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

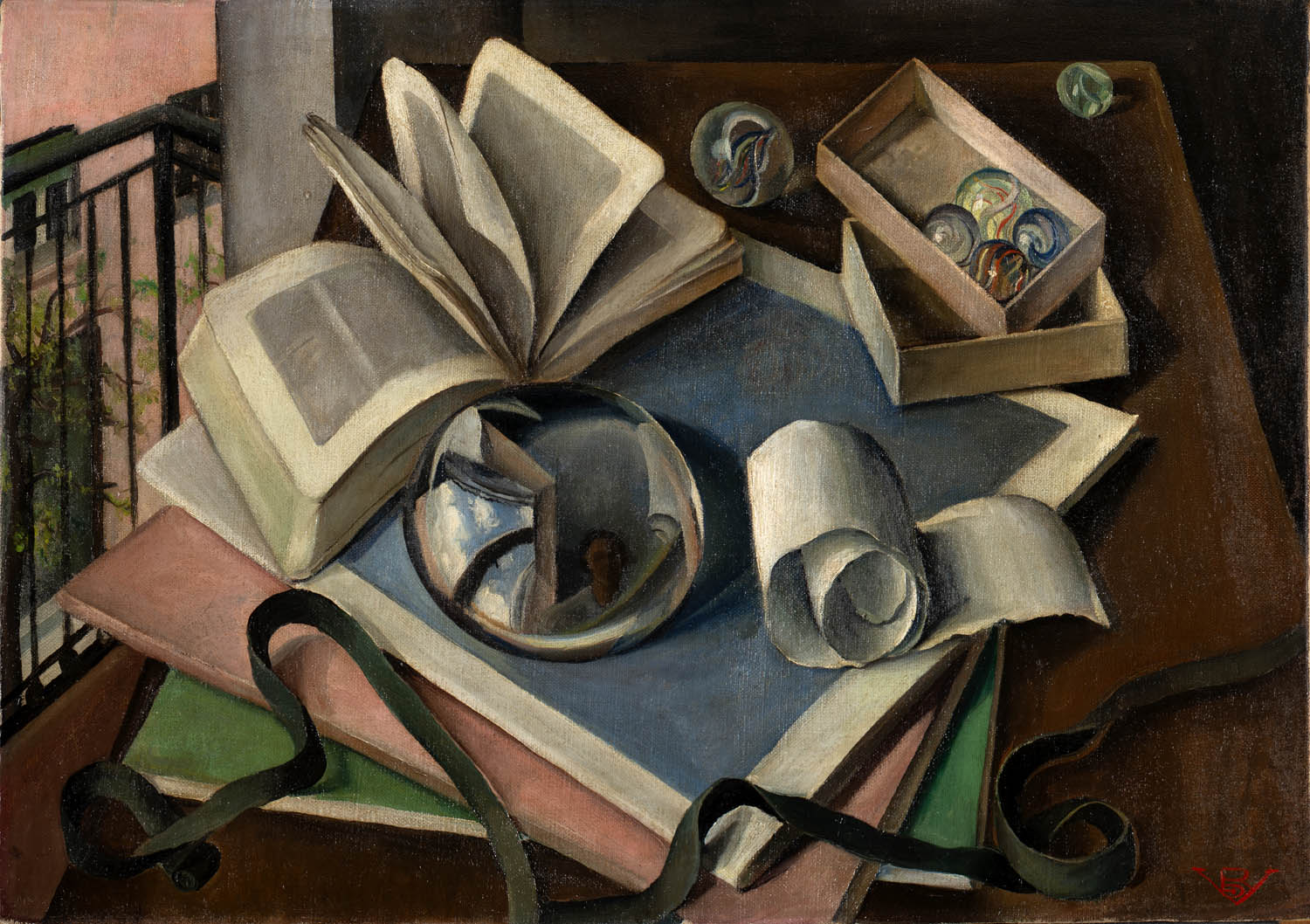

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Things (Cosas)

1933

Oil on canvas

45.5 × 65.5cm

Private collection

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Untitled, (The Children’s Room) / Sin título (El cuarto de los niños)

1932-1933

Oil on canvas

55 × 73cm

Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

Photo: Archivo Fotográfico Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco remains one of the least known artists of the 1930s in Spain. Her academic training in Madrid took place alongside Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor and, above all, was the result of her avid curiosity for the Italian Novecento and the German New Objectivity. This interest came to her through magazines and the contemplation of the work of authors such as Carlo Carrà, Felice Casorati and Ardengo Soffici at the Palacio de Exposiciones del Retiro in 1928.

Her approach to the ideas of the Falange Española de las JONS and José Antonio Primo de Rivera led her to collaborate with the magazine Vértice between 1937 and 1946, where she illustrated the ideology of the new regime. In this context we must place the canvas The Massacre of the Innocents (1936), in which Rosario de Velasco used a religious theme to create a work with clear political content created with the aim of mobilising society. The work was presented at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts inaugurated on July 4, 1936 by the President of the Republic, Manuel Azaña, at the Palacio de Cristal in Madrid.

This drift from realism towards political action was a frequent trend at a turbulent time in the history of Spain when art was placed at the service of propaganda. However, with democracy, the exiled and forgotten republican artists were recovered, Rosario de Velasco was ignored both for her genre and for her ideology. The flood of 1957 only deepened the marginalisation of The Massacre of the Innocents and left the painting covered in mud and with water marks for years. The magnificent and disturbing work was attributed to Ricardo Verde based on the monogram with which Rosario de Velasco signed her works, with the initials of her name, RV, until in 1995 its authorship was returned to the artist.

Anonymous. “La matanza de los inocentes,” on the on the Museo Belles Arts Valencia website Nd [Online] Cited 05/09/2024. Translated by Google Translate from the Spanish text

The Spanish Civil War marked a turning point in Rosario’s life. Her Falangist militancy and her family environment led her to leave Madrid, traveling first to Valencia and then to Barcelona, where she met the doctor Javier Farrerons, who would become her husband. Thanks to Farrerons, Rosario was released from the Modelo prison in Barcelona, where she was detained. After the war, he settled in Barcelona with his family and continued to participate in various exhibitions, albeit less frequently.

In 1939, she participated in the National Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture in Valencia, and in 1940 she presented her first individual exhibition in Barcelona. Over the following years, she also exhibited in Madrid, at events such as the National Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1941 and 1954, as well as in various galleries. In 1944, she was selected for the II Salón de los Once, organised by the Academia Breve de Crítica de Arte, an initiative by Eugenio d’Ors to promote post-war art.

Redacción. “Rosario de Velasco: Entre Giotto y Picasso, un estilo único en la pintura española,” (Rosario de Velasco: Between Giotto and Picasso, a unique style in Spanish painting) on the GenexiGente website 28/05/2024 [Online] Cited 14/08/2024, Translated from the Spanish by Google Translate

The outbreak of the Civil War, her Falangist militancy and her family environment lead her to leave Madrid. She travels first to Valencia and then to Barcelona, in Sant Andreu de Llavaneres, where she meets the ophthalmologist Javier Farrerons, her future husband, and who managed to free her from the Modelo prison in Barcelona, where she was detained. Viudes de Velasco explains that “thanks to God, she was in prison for one night because she had the immense luck that the doctor in the prison was a very good friend of the one who later became her husband, and that same night they took her out. The next day her cellmate was shot. That marked her life and she didn’t want to talk about the war again.”

Cristina Perez. “La fuerza bíblica de Rosario de Velasco ilumina el Museo Thyssen,” (The biblical force of Rosario de Velasco illuminates the Thyssen Museum) on the rtve website 18.06.2024 [Online] Cited 14/08/2024. Translated from the Spanish by Google Translate

Dora Maar (French, 1907-1997)

Guernica

May-June, 1937

Gelatin silver print

This photograph is not in the exhibition and is used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research.

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

The Massacre of the Innocents (La matanza de los inocentes)

1936

Oil on canvas

164 × 167.5cm

Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia

Photo: Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

The Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza is jointly presenting with the Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia an exhibition on the Spanish figurative painter Rosario de Velasco (Madrid, 1904 – Barcelona, 1991). Curated by Miguel Lusarreta and Toya Viudes de Velasco, the artist’s great-niece, the exhibition brings together around 30 paintings from the 1920s to the 1940s – the earliest and the most important from Velasco’s career – and also has a section on her work as an illustrator.

The exhibition, which is benefiting from the support of the Region of Madrid and the City Council of Madrid, aims to present and draw attention to the work of one of the great Spanish women artists of the first half of the 20th century. In addition to well-known paintings from museum collections, such as the famous oil Adam and Eve (1932) from the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, The Massacre of the Innocents (1936) from the Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia, Maragatos (1934) from the Museo del Traje, Madrid, and Carnival (before 1936) from the Centre Pompidou, Paris, the exhibition features works still with the artist’s family and in private collections and others that have only been rediscovered and located in the past few months. Following its showing in Madrid, the exhibition will be presented at the Museo de Bellas Artes de Valencia from 7 November 2024 to 16 February 2025.

Rosario de Velasco’s work represents an outstanding example of the so-called “return to order” in Spain, a movement parallel to German New Objectivity and Italian Novecento with a style that combined tradition and modernity. Velasco admired painters such as Giotto, Masaccio, Piero della Francesca, Mantegna, Velázquez and Goya, but also avant-garde figures such as De Chirico, Braque, Picasso and the exponents of the “return to order” in Germany and Italy, whom she encountered via magazines and exhibitions held in Madrid in the 1920s.

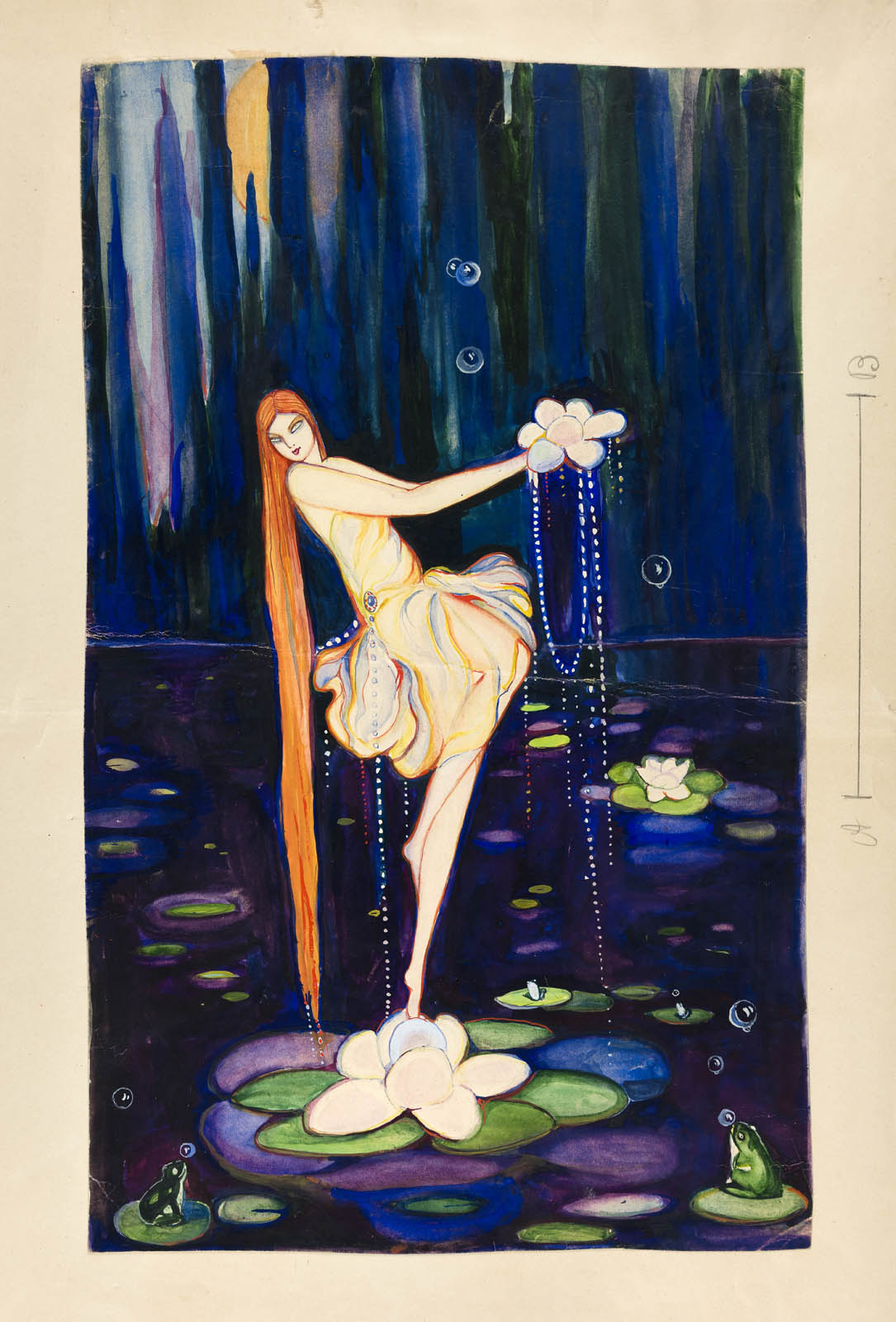

The exhibition also focuses on Velásco’s activities as an illustrator, revealing a graphic artist of great versatility. This is evident, for example, in her illustrations for the 1928 edition of Stories for dreaming by María Teresa León and Stories for my grandchildren (1932) by Carmen Karr.

Rosario de Velasco (Madrid, 1904 – Barcelona, 1991)

Born into a very traditional and religious family in Madrid, Rosario de Velasco began to study art aged fifteen at the academy of the genre painter Fernando Álvarez de Sotomayor, a member of the Royal San Fernando Academy of Fine Arts and two-time director of the Museo del Prado. Dating from that period is her Self-portrait (1924), which she signed with a monogram consisting of the initials R, D and V. Inspired by Dürer’s monogram, it has been fundamental to locating some of the artist’s paintings.

The young artist was, however, aware that she needed to go beyond tradition and assimilate the new trends and avant-gardes in her desire to compete as an equal in a largely male world. Her openness and cultural curiosity led her to associate with numerous creators of her generations, particularly women painters and writers such as Maruja Mallo, Rosa Chacel and María Teresa León. Other women friends included Mercedes Noboa, Matilde Marquina, Concha Espina and Lilí Álvarez, the tennis champion whom Velasco painted in the 1930s and with whom she enjoyed playing the sport. De Velasco was also a tireless traveller and enjoyed mountaineering, skiing and rock climbing.

In 1924, the year she completed her studies, the artist participated in the National Fine Arts Exhibition in Madrid and also produced her first illustrations. By the 1930s Rosario de Velasco had established a considerable reputation, taking part in numerous group shows and competitions, such as the National Fine Arts Exhibition of 1932 in which she presented the canvas Adam and Eve, which earned her a second prize medal in the Painting category. The work was exhibited together with all the other entries in the Palacio de Exposiciones in the Retiro park and in various exhibitions organised by the Society of Iberian Artists held in Copenhagen and Berlin, where it was warmly praised by critics for its power and originality and Velasco was singled out as the major discovery of the season. The work is startling in its play of perspective, employing a bird’s-eye view, a device also used in various still lifes and in (Untitled) The Children’s Room (1932-33), another work in the collection of the Museo Reina Sofía, in which the artist disrupts the space through an original arrangement of objects that recalls Cubism.

The majority of Velasco’s most important works date from that decade: Maragatos, which was awarded second prize in the National Painting competition of 1932; The Massacre of the Innocents (1936), which for many years was attributed to Ricardo Verde due to the signature “RV”, until it was correctly attributed to De Velasco in 1995; and Laundresses (1934), a wedding gift to her brother, Dr Luis de Velasco, who appears in another work in the present exhibition.

In 1935 Gypsies was selected to participate in the Carnegie International, an exhibition of artists from different countries organised by the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. Velasco’s work shared space with that of Carlo Carrá, Otto Dix, Edward Hopper and Georgia O’Keeffe, as well as Picasso and Dalí. Lost for years, the painting has only recently been located and is one of the major discoveries made during the preparation of this exhibition.

On the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War the artist’s membership of the Falange and her family context led her to leave Madrid. She went first to Valencia and later to Barcelona, to Sant Andreu de Llavaneres where she met a doctor, Javier Farrerons, who later became her husband and who succeeded in liberating her from the Modelo prison in Barcelona where she was being held. After the war the artist settled in Barcelona with her husband and their daughter María del Mar.

In 1939 Velasco participated in the National Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture in Valencia and in 1940 presented her first solo exhibition, in Barcelona. Over the following years she continued to exhibit in Madrid although less often, for example at the National Fine Arts Exhibitions of 1941 and 1954, and at various galleries. In 1944 Velasco was selected for the 2nd Salón de los Once, organised by the Academia Breve de Crítica de Arte, founded by Eugenio d’Ors to promote art of the immediate post-war period. D’Ors was one of the well known figures in the artist and her husband’s circle of friends, together with Dionisio Ridruejo, Pere Pruna and Carmen Conde, among others.

The recent search for works by Velasco which was undertaken via the social media and the media in general has resulted in the identification in private collections of both celebrated works of which all trace had been lost, such as Things (1933), Motherhood (1933), Gypsies (1934) and Pensive Woman (1935), as well as various illustrations for books and a preparatory drawing for the oil painting Carnival (before 1936). It has also brought to light some previously completely unknown works such as Still Life with Fish (c. 1930) and Girls with a Doll (1937).

Press release from the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

The Bluebird, drawing for the cover of María Teresa León’s book Cuentos para soñar (El pájaro azul 1927. Dibujo para la cubierta del libro Cuentos para soñar de María Teresa León, 1927)

1927

Mixed media on paper

41 x 27.5cm

Gonzalez Rodriguez Collection

Photo: Jonás Bel

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

The White Leaves of a Waterlily Half Opened, drawing for María Teresa León’s book Cuentos para soñar (Las blancas hojas de nenúfar se entreabrieron, 1927. Dibujo para el libro Cuentos para soñar de María Teresa León)

1927

Mixed media on paper

50 × 32.3cm

Gonzalez Rodriguez Collection

Photo: Jonás Bel

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

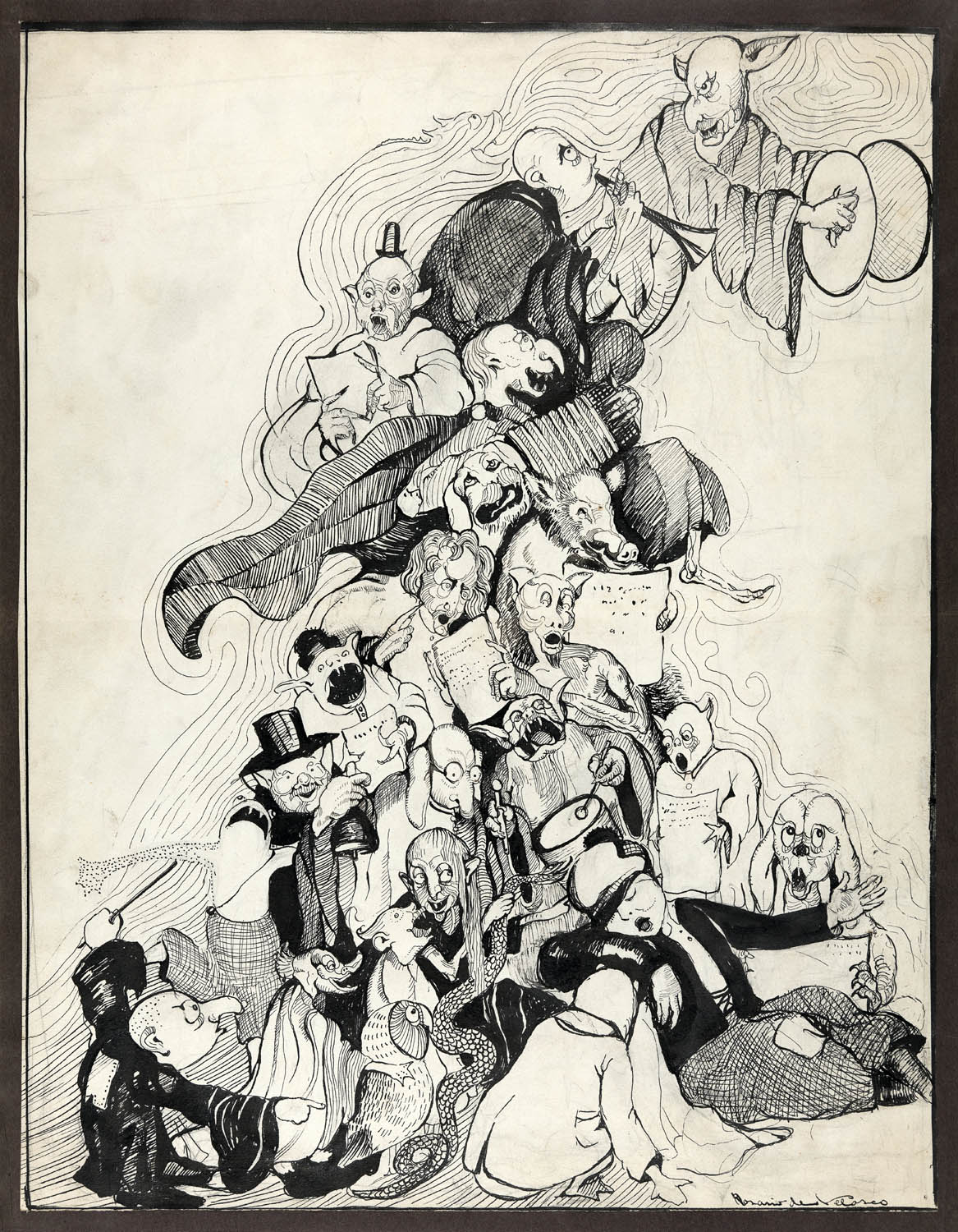

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

The Hullabaloo Gave Him Serious Nightmares, drawing for María Teresa León’s book Cuentos para soñar (Tales to dream about) (La algarabía ciudadana proporcionó serias pesadillas, 1927. Dibujo para el libro Cuentos para soñar de María Teresa León)

1927

Ink on paper

42.3 × 32.5cm

Gonzalez Rodriguez Collection

Photo: Jonás Bel

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

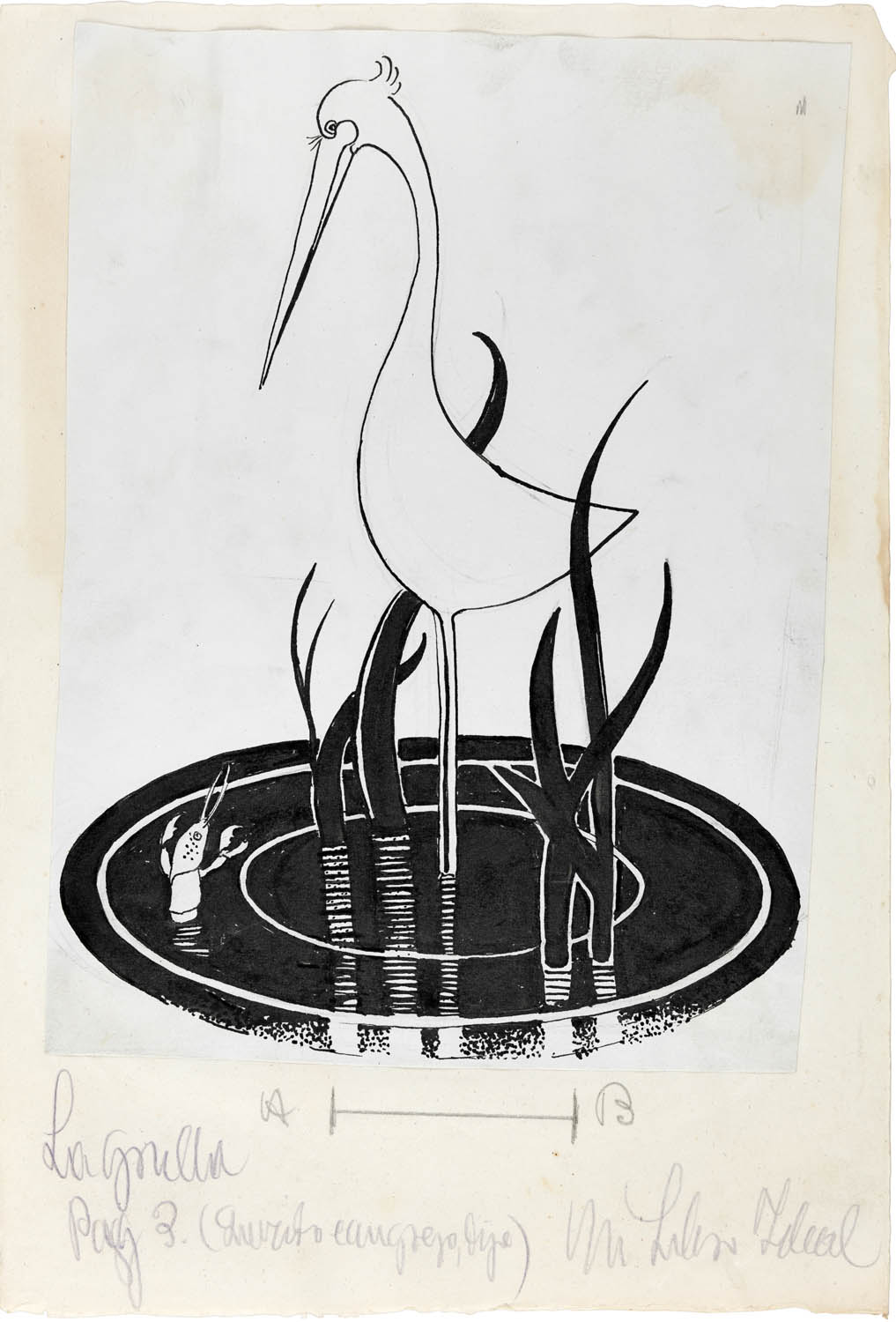

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Dear Crab, Leave the Crane, drawing for Mi libro ideal (Querido cangrejo, deja la grulla, 1933. Dibujo para Mi libro ideal de varios autores)

1933

Ink on paper

31.2 × 21.4cm

Gonzalez Rodriguez Collection

Photo: Jonás Bel

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Motherhood (Maternidad)

1933

Oil on canvas

99 × 89cm

Private collection

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Gypsies (Gitanos)

1934

Oil on canvas

95 × 132cm

Private collection

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Otto Dix (German, 1891-1969)

Reclining Woman on a Leopard Skin

1927

Oil paint on panel

680 x 980mm

© DACS 2017. Collection of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University. Gift of Samuel A. Berger

This painting is not in the exhibition and is used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research.

Dix was a key supporter of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement, a name coined after an exhibition held in Mannheim, Germany in 1925. Described by art historian G.F. Hartlaub, as ‘new realism bearing a socialist flavour’, the movement sought to depict the social and political realities of the Weimar Republic.

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Woman with Towel (Mujer con toalla)

1934

Oil on canvas

82 × 76cm

Private collection

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Pensive Woman (Pensativa)

1935

Oil on canvas

57.5 × 72cm

Emilia Casal Piga and Guillermo González Hernández Collection

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Installation view of the exhibition Rosario de Velasco at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza showing at left, de Velsaco’s Laundresses / The Washerwomen (Lavanderas) 1934 (below)

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Laundresses / The Washerwomen (Lavanderas)

1934

Oil on canvas

209 × 197cm

Private collection

Photo: Jonás Bel

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Maragatos

1934

Oil on canvas

210 × 150cm

Museo del Traje, Madrid

Photo: Museo del Traje. Centro de Investigación del Patrimonio Etnológico, Madrid

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Carnival (Carnavalina)

1936

Watercolour and graphite on cardboard

29.7 × 21.2cm

Fundación Colección ABC

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Carnival (Carnaval)

Prior to 1936

Oil on canvas

115 × 110cm

Centre Pompidou, París, Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle, adquisición del Estado, 1936

Photo: Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Bertrand Prévost

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Installation view of the exhibition Rosario de Velasco at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza showing de Velsaco’s Retrato de la familia Bastos (Portrait of the Bastos family) 1936 Oil on canvas

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Girls with Doll (Niñas con muñeca)

1937

Oil on canvas

84.7 × 61.8cm

Private collection

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Installation view of the exhibition Rosario de Velasco at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza showing at left, de Velsaco’s Lilí Álvarez 1938 (below)

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

Lilí Álvarez

1938

Oil on board

97.8 × 71.8cm

Lopez-Chicheri Daban Family Collection

Photo: Jonás Bel

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Rosario de Velasco (Spanish, 1904-1991)

María del Mar en Vilanova

1943

Oil on canvas

117 × 89cm

Private collection

© Rosario de Velasco, VEGAP, Madrid, 2024

Anonymous photographer

Rosario de Velasco painting

1920s

Anonymous photographer

Rosario de Velasco painting ‘Laundresses / The Washerwomen’ (Lavanderas)

1934

Archive of the Rosario de Velasco family

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza

Paseo del Prado, 8. 28014, Madri

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday, 10am – 7pm

Saturdays, 10 am – 9 pm

Closed on Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.