Exhibition dates: 16th October, 2009 – 28th February, 2010

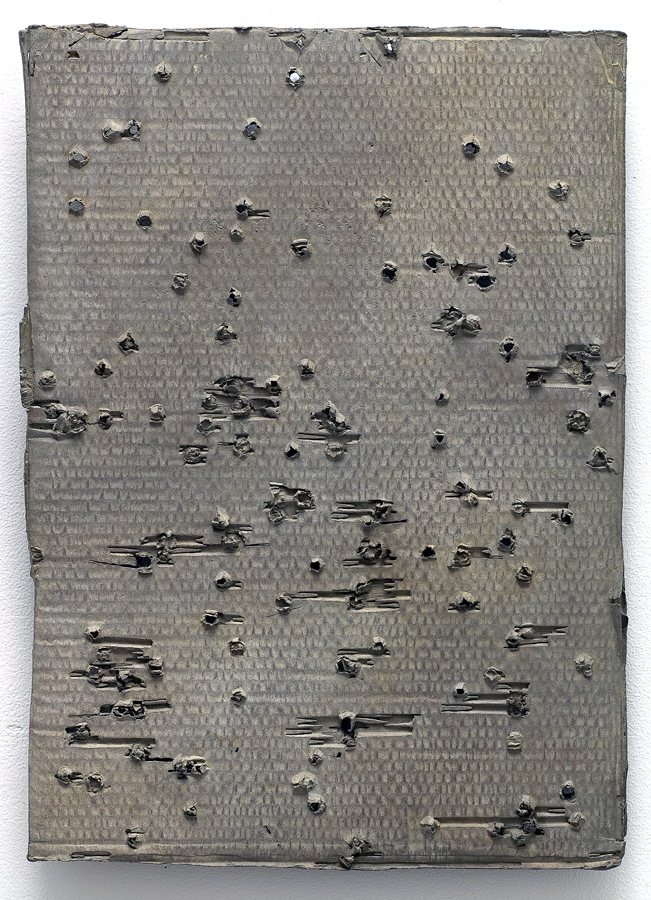

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-2006, United States 2006- )

Salad days

c. 2005

Jelutong (Dyera costulata), maple (Acer sp.)

102.0 x 102.0 x 23.8cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased with funds from the Victorian Foundation for Living Australian Artists, 2005

© Ricky Swallow

Photo: Andy Keate courtesy Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney

“Curiosity is a vice that has been stigmatized in turn by Christianity, by philosophy and even by a certain conception of science. Curiosity, futility. I like the word however. To me it suggests something all together different: it evokes concern; it evokes the care one takes for what exists or could exist; an acute sense of the real which, however, never becomes fixed; a readiness to find our surroundings strange and singular; a certain restlessness in ridding ourselves of our familiarities and looking at things otherwise; a passion for seizing what is happening now and what is passing away; a lack of respect for traditional hierarchies of the important and the essential.”

Michel Foucault 1

“Swallow is at his best when he’s exploring ways to communicate through the innate qualities of materials … This is always going to be more affecting than glib post-modernism, but he just can’t help himself sometimes. So my deep dislike for portentous and ironic titles bristled up immediately here. ‘Salad Days’ and ‘Killing Time’ are only two of the jokey puns, the problem is that art that simply supports two meanings isn’t very smart or complex. There’s no room for subtext. Irony is not the complex and neutral form that ambiguity is. It doesn’t invite engagement or interpretation. Art ought to aspire to infinite meanings, or maybe even only one. Irony doesn’t make for good art, when irony is the defense mechanism against meaning, masking an anxiety about sincerity.”

John Matthews 2

Let’s cut through the hyperbole. This is not the best exhibition since sliced bread (“the NGV highlight of 1609, 2009 and possibly 2109 too” says Penny Modra in The Age) and while it contains a few strong individual pieces this is not even a particularly good exhibition by Ricky Swallow at NGV Australia.

Featuring bronzes, watercolours and sculptures made from 2004-2009 that are sparingly laid out in the gallery space this exhibition comes as close to the National Gallery of Victoria holding a commercial show as you will find. Using forms such as human skeletons, skulls, balloons encrusted with barnacles, dead animals and pseudo death masks that address issues of materials and memory, time and space, discontinuity and death, Swallow’s sculptures are finely made. The craftsmanship is superb, the attention to detail magnificent and there is a feeling of almost obsessional perfectionism to the pieces. This much is given – the time and care taken over the construction, the hand of the maker, the presentation of specimen as momento mori is undeniable.

After seeing the exhibition three times the standout pieces for me are a life size dead sparrow cast in bronze (with the ironic title Flying on the ground is wrong 2006) – belly up, prostrate, feet curled under – that is delicate and poignant; Caravan (2008), barnacle encrusted bronze balloons that play with the ephemerality of life and form – a sculpture that is generous of energy and spirit, quiet yet powerful; Bowman’s record (2008), found objects of paper archery targets cast in bronze, the readymade solidified, the marks on paper made ambiguous hieroglyph of non-decaying matter, paper / bronze pierced by truth = I shot this, I was here (sometime); and Fig.1 (2008), a baby’s skull encased in a paper bag made of carved wood – the delicacy of surfaces, folds, the wooden paper collapsing into the skull itself creating the wonderful haunting presence of this piece. In these sculptures the work transcends the material state to engage the viewer in a conversation with the eternal beyond.

Swallow seeks to evidence the creation of meaning through the humblest of objects where the object’s fundamental beauty relies on the passing of time for its very existence. In the above work he succeeds. In other work throughout the exhibition he fails.

There seems to be a spare, international aesthetic at work (much like the aesthetic of the Ron Mueck exhibition at NGV International on St. Kilda Road). The art is so kewl that you can’t touch it, a dude-ish ‘Californication’ having descended on Swallow’s work that puts an emotional distance between viewer and object. No chthonic nature here, no dirt under the fingernails, no blood on the hands – instead an Apollonian kewlness, all surface and show, that invites reflection on life as discontinuous condition through perfect forms that seem twee and kitsch.

In Tusk (2007) two bronze skeletal arms hold hands in an undying bond but the sculpture simply fails to engage (the theme was brilliantly addressed by Louise Bourgeois in the first and only Melbourne Arts Biennale in 1999 with her carving in granite of two clasped hands); in History of Holding (2007) the icon of the Woodstock festival designed in 1969 is carved into a log of wood placed horizontally on the floor while a hand holding a peeled lemon (symbolising the passing of time in the still life genre) is carved from another log of wood placed vertically. One appreciates the craftmanship of the carving but the sentiments are too saccharin, the surfaces too shallow – the allegorical layering that Swallow seeks stymied by the objects iconic form. A friend of mine insightfully observed about the exhibition: “Enough of the blond wood thing – it’s so Space Furniture!”

As John Matthews opines in the above quotation from his review of the exhibition there seems to be a lack of sincerity and authenticity of feeling in much of Swallow’s work. Irony as evidenced in the two major pieces titled Salad Days (2005) and Killing Time (2003-2004) leaves little room for the layering of meaning: “Irony is not the complex and neutral form that ambiguity is. It doesn’t invite engagement or interpretation.” Well said.

Killing Time in particular adds nothing to the vernacular of Vanitas paintings of the 17th century, adds nothing to the mother tongue of contemporary concerns about the rape of the seas, fails to update the allegories of the futility of pleasure and the inevitability of death – in fact the allegories in Swallow’s sculpture, the way he tries to twist our conception of the real, seem to have lost the power to remind us of our doom. The dead wooden fish just stare back at us with doleful, hollow eyes. The stilted iconography has no layering; it does not destroy hierarchies but builds them up.

In his early work Swallow was full of curiosity, challenging the norms of culture and creation. I always remember his wonderful series of dioramas at the Melbourne Biennale that featured old record players and animated scenes (see the photograph of Rooftop shoot out with chimpanzee (1999) below). Wow they were hot, they were fun, they made you think and challenge how you viewed the world! As Foucault notes in his excellent quotation at the top of the posting, curiosity promotes “an acute sense of the real which, however, never becomes fixed; a readiness to find our surroundings strange and singular; a certain restlessness in ridding ourselves of our familiarities and looking at things otherwise; a passion for seizing what is happening now and what is passing away; a lack of respect for traditional hierarchies of the important and the essential.”

While Swallow’s ‘diverse gestures of memorialisation’ still address the fundamental concerns of Foucault’s quotation his work seems to have become fixed in an Apollonian desire for perfection. He has forgotten how his early work challenged traditional hierarchies of existence; now, even as he twists and turns around a central axis, the conceptualisation of life, memory and death, his familiarity has become facsimile (a bricoleur is a master of nothing, a tinkerer fiddling at the edges). His lack of respect has become sublimated (“to divert the expression of (an instinctual desire or impulse) from its unacceptable form to one that is considered more socially or culturally acceptable”), his tongue in cheek has become firmly fixed, his sculptures just hanging around not looking at things otherwise.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Foucault, Michel. “The Masked Philosopher” in Politics, philosophy, culture: interviews and other writings, 1977-1984. London: Routledge, 1988, p. 328

2/ Matthews, John. “On Ricky Swallow @ NGV” on ArtKritique [Online] Cited 02/02/2010

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-06, United States 2006- )

Rooftop shoot out with chimpanzee

1999

From the series Even the odd orbit

Cardboard, wood, plastic model figures and portable record player

53.0 h x 33.0 w x 30.0 d cm

Collection of the National Gallery of Australia

Gift of Peter Fay 2001

Please note: This art work is not in the exhibition

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-06, United States 2006- )

Tusk (detail)

2007

Patinated bronze, brass

Edition of 3 plus 1 Artist’s Proof

50 x 105 x 6cm

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Gift of the Prescott Family Foundation, 2008

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-06, United States 2006- )

The Man from Encinitas

2009

Plaster, onyx, steel

Ricky Swallow’s sculptures address fundamental issues that lie at the core of who we are. Things have lives. We are our things. We are things. When all is said and done it is our things – our material possessions – that outlive us. Anyone who has lost a family member or close friend knows this: what we have before us once that person is gone are the possessions that formed a life. Just as we are defined and represented by the things that we collect over time, we are ultimately objects ourselves. When we are dead and decomposed what remains are our bones, another type of object. And then there is social science. Archaeology, a subfield of anthropology, is entirely based on piecing together narratives of human relations based on material culture, that is, objects both whole and fragmentary. It may seem obvious but it is worth stressing here that our understanding of cultures from the distant past, those that originated before the advent of writing, is entirely based on the study of objects and skeletal remains. Swallow’s art addresses these basic yet enduring notions and reminds us of our deep symbiotic relationship to the stuff of daily life.

Like the bricoleur put into popular usage by anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss in his seminal book The Savage Mind, Ricky Swallow creates works of art often based on objects from his immediate surroundings. His method, however, is more of a second order bricolage: his sculptures are not assemblages of found objects, but rather elegantly crafted things. Handcarved from wood or plaster or cast in bronze, these humble objects are transformed into memorials to both the quotidian and the passage of time.

Still life

The still life has been an important touchstone throughout Swallow’s recent practice as it is an inspired vehicle for the exploration of how meaning is generated by objects. Several sculptures in the exhibition reference the still-life tradition in which Swallow updates and personalises this time-honoured genre, in particular the vanitas paintings of 17th century Holland. Vanitas still lifes, through an assortment of objects that had recognisable symbolism to a 17th-century viewer, functioned as allegories on the futility of pleasure and the inevitably of death. Swallow’s embrace of still life convention, however, is non-didactic, secular and open-ended. Swallow is not obsessed by death. On the contrary, his focus on objects is about salvaging them from the dust bin of history and honouring their continued resonance in his life.

Killing time, 2003-2004, and Salad days, 2005, depict animals that Swallow and his family either found or caught when he was young and best highlight how the artist reclaims the still life genre to explore personal narrative. Killing time, which depicts a bounty of fish and crustaceans spread across a table modelled after the Swallow family kitchen table of the artist’s youth, is rife with autobiographical association. It not only references an object from Swallow’s past, but also the profession of his father, a fisherman, and the fact that Swallow was raised by the sea. Salad days is another autobiographical work depicting a range of animals such as birds, a rabbit, mice and a fox skull. Like many boys growing up in rural environments, Swallow recalls shooting magpies, encountering nesting birds in his garage or discovering dead lizards or trapping live ones in an attempt to keep them as pets.

While not an overt still life, History of holding, 2007, suggests the genre in its fragmentary depiction of a musical instrument and the appearance of a lemon with falling rind. The hand holding / presenting a peeled lemon as the rind winds around the wrist in bracelet-like fashion is based on a cast of Swallow’s own hand, insinuating himself into this antiquated tradition. It is as if Swallow is announcing to us his deep interest in the temporality of objects through the presentation of the peeled lemon, which symbolises the passing of time and also appears in Killing time. The second component of History of holding is a sculptural interpretation of the Woodstock music festival icon designed by Arthur Skolnick in 1969, which still circulates today. History of holding, then, also references music, a leitmotif in Swallow’s art that appears both within the work itself, and also through Swallow’s use of titles.

Body fragments

Tusk, 2007 among several other works in the exhibition, explores the theme of body as fragment. Much has been discussed about Swallow’s use of the skeleton as a form rich in meaning within both the traditions of art history as well as popular culture (references range from the Medieval dance macabre and the memento mori of the still life tradition to the skeleton in rock music and skateboard art iconography). Tusk represents two skeletal arms with the hands clasped together in eternal union. A poignant work, Tusk is a meditation on permanence: the permanence of the human body even after death; the permanence of the union between two people, related in the fusion of the hands into that timeless symbol of love, the heart.

Watercolours: atmospheric presentations, mummies, music, homage

Swallow calls his watercolours “atmospheric presentations,” in contradistinction to his obviously more physical sculptures, and he sees them as respites from the intensity of labour and time invested in the sculptural work. They also permit experimentation in ways that sculpture simply does not allow. One nation underground, 2007, is a collection of images based on rock / folk musicians, several who had associations to 1960s Southern California, Swallow’s current home. Most of the subjects Swallow has illustrated in this work are now deceased; several experienced wide recognition only after their deaths. Like many of his sculptures, this group of watercolours tenderly painted with an air of nostalgia has the sensibility of a memorial – or as Swallow has called it “a modest monument”. The title of the work is based on a record album by another under-heralded rock band from the 1960s, Pearls Before Swine, and is a prime example of Swallow’s belief in the importance of titles to the viewing experience as clues or layers of meaning. In this case, the title hints at the quasi-cult status of the musicians and singers depicted. The featured musicians are Chris Bell (Big Star), Karen Dalton (a folk singer), Tim Buckley (legendary singer whose style spanned several genres and father to the late Jeff Buckley), Denny Doherty (The Mamas & the Papas ), Judee Sill (folk singer), Brian Jones (Rolling Stones), Arthur Lee (Love), John Phillips (The Mamas & the Papas ), Skip Spence (Jefferson Airplane and Moby Grape) and Phil Ochs (folk singer).

Text from the NGV website

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-2006, United States 2006- )

Killing Time

2003-04

Laminated Jelutong, maple

108.0 x 184.0 x 118.0cm (irreg.)

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Rudy Komon Memorial Fund and the Contemporary Collection Benefactors 2004

© Ricky Swallow. Courtesy Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney

Killing time, 2003-2004, and Salad days, 2005, depict animals that Swallow and his family either found or caught when he was young and best highlight how the artist reclaims the still life genre to explore personal narrative. Killing time, which depicts a bounty of fish and crustaceans spread across a table modelled after the Swallow family kitchen table of the artist’s youth, is rife with autobiographical association. It not only references an object from Swallow’s past, but also the profession of his father, a fisherman, and the fact that Swallow was raised by the sea. Salad days is another autobiographical work depicting a range of animals such as birds, a rabbit, mice and a fox skull. Like many boys growing up in rural environments, Swallow recalls shooting magpies, encountering nesting birds in his garage or discovering dead lizards or trapping live ones in an attempt to keep them as pets.

Text from the National Gallery of Victoria

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-2006, United States 2006- )

Killing Time (detail)

2003-04

Laminated Jelutong, maple

108.0 x 184.0 x 118.0cm (irreg.)

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Rudy Komon Memorial Fund and the Contemporary Collection Benefactors 2004

© Ricky Swallow. Courtesy Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney

“I’ve always been interested in how an object can be remembered and how that memory can be sustained and directed sculpturally, pulling things in and out of time, passing objects through the studio as a kind of filter returning them as new forms.”

Ricky Swallow in Goth: Reality of the Departed World. Yokohama: Yokohama Museum of Art, 2007

A new exhibition featuring the work of internationally renowned Australian artist Ricky Swallow will open at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia on 16 October 2009.

Ricky Swallow: The Bricoleur is the artist’s first major exhibition in Australia since 2006. This exhibition will feature several of the artist’s well‐known intricately detailed, carved wooden sculptures as well as a range of new sculptural works in wood, bronze and plaster. The exhibition will also showcase two large groups of watercolours, an aspect of Swallow’s practice that is not as well known as his trademark works.

Salad days (2005) and Killing time (2003‐2004), which were featured in the 2005 Venice Biennale and are considered Swallow icons, will strike a familiar chord with Melbourne audiences.

Sculptures completed over the past year include bronze balloons on which bronze barnacles seamlessly cling (Caravan, 2008); a series of cast bronze archery targets (Bowman’s Record, 2008) that look like desecrated minimalist paintings; and carved wooden sculpture of a human skull inside what looks like a paper bag.

A highlight of the show will be Swallow’s watercolour, One Nation Underground (2007), recently acquired by the NGV. The work presents a collection of images based on 1960s musicians including Tim Buckley, Denny Doherty, Brian Jones and John Phillips.

Alex Baker, Senior Curator, Contemporary Art, NGV said the works in this exhibition explore the themes of life and death, time and its passing, mortality and immortality.

“Swallow’s art investigates how memory is distilled within the objects of daily life. His work addresses the fundamental issues that lie at the core of who we are, reminding us of our deep symbiotic relationship to the stuff of everyday life.”

“The exhibition’s title The Bricoleur refers to the kind of activities performed by a handyman or tinkerer, someone who makes creative use of whatever might be at hand. The Bricoleur is also the title of one of the sculptures in the exhibition, which depicts a forlorn houseplant with a sneaker wedged between its branches,” said Dr Baker.

Gerard Vaughan, Director, NGV, said this exhibition reinforces the NGV’s commitment to exhibiting and collecting world‐class contemporary art.

“The NGV has enjoyed a long and successful relationship with Ricky Swallow, exhibiting and acquiring a number of his works over the years. His detailed and exquisitely crafted replicas of commonplace objects never fail to inspire visitors to the Gallery.”

Ricky Swallow was born in Victoria in 1974 and currently lives and works in Los Angeles, California. His career has enjoyed a meteoric rise since winning the NGV’s prestigious Contempora5 art prize in 1999. Since then, Swallow has exhibited in the UK, Europe and the United States, and represented Australia at

the 2005 Venice Biennale.

Press release from the NGV

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-2006, United States 2006- )

A sad but very discreet recollection of beloved things and beloved beings (detail)

2005

Watercolour

(1-10) 35.0 x 28.0cm (each)

Private collection

© Ricky Swallow

Photo: courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-2006, United States 2006- )

Bowman’s record (detail)

2008

Bronze

46.0 x 33.0 x 2.5cm

Collection of the artist, Los Angeles

© Ricky Swallow

Photo: Robert Wedemeyer courtesy Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London

Ricky Swallow (born Australia 1974, lived in England 2003-2006, United States 2006- )

The Bricoleur (detail)

2006

Jelutong (Dyera costulata)

122 x 25 x 25cm

Private collection

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia Federation Square

Corner of Russell and

Flinders Streets, Melbourne

Opening hours:

Open daily 10am-5pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.