Exhibition dates: 3rd August – 30th September 2012

Artists: Andrew Browne, John Cato, Jo Daniell, John Delacour, Peter Elliston, Joyce Evans, Chantel Faust, Susan Fereday, Anthony Figallo, George Gittoes, John Gollings, Graeme Hare, Melinda Harper, Paul Knight, Peter Lambropoulos, Bruno Leti, Anne MacDonald, David Moore, Grant Mudford, Harry Nankin, Ewa Narkiewicz, John Nixon, Rose Nolan, Jozef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski, Robert Owen, Wes Placek, Susan Purdy, Scott Redford, Jacky Redgate, Wolfgang Sievers, David Stephenson, Mark Strizic and Rick Wood.

John Gollings (Australia, b. 1944)

Untitled

1988

From the series Bushfire aerials

Gelatin silver print

45.5 x 56.0cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the artist

Dropping the abstract ball

There are some excellent works in this interestingly themed exhibition at the Monash Gallery of Art. Unfortunately the exhibition, the theme and the work are let down by two curatorial decisions. Before I address those issues I will give my insight into some of the work presented:

~ A wonderful print of Sisters of Charity, Washington DC by David Moore (1956) where the starched cornettes of the sisters reminded me of paper doves. The kicker or punctum in this image is the hand of one of the sisters pointing skywards/godwards

~ Wonderful David Stephenson Star Drawing. I always like photographs from this series. Taken in Central Australia using as many as 72 multiple exposures, Stephenson used a set of rules for each exposure – deciding on the length and amount of exposure and how far he would rotate the camera between each exposure before embarking on the creation of each image. The construction of the image was pre-determined but because of the movement of the earth and stars over a couple of hours, the result always incorporated an element of chance. Stephenson draws with light that is millions of years old, the source of which may not exist by the time the light falls on Stephenson’s photographic plate (the star might be dead)

~ John Gollings Untitled from the Bushfire series. Beautiful, luminous black and white silver gelatin prints of tracks in bushfire affected areas. These aerial photographs make the surface of the earth seem like the surface of the skin complete with hairs and wrinkles. In process they reference the New Topographics exhibition of 1975, where the mapping of the landscape is etched into the surface of the photographic print, where the pictorial plane records the environment like the marks on an etching plate. “The pictures were stripped of any artistic frills and reduced to an essentially topographic state, conveying substantial amounts of visual information but eschewing entirely the aspects of beauty, emotion and opinion.”

~ The beautiful Scott Redford Urinal photographs where the subject becomes secondary to the abstract visual elements as the flash bounces off the metal surfaces. Tight camera angles and a limited colour palette cause an almost transcendent composition. The swirls and markings and the sword-like quality of the central image (see below) remind me of Excalibur rising from the lake, dripping water.

~ Four photographs by John Cato, one each from Petroglyph 1971-79, Waterway 1971-79, Proteus 1971-79 and Tree – a journey 1971-79. These were incredibly beautiful and moving photographs, abstractions of the natural world. You need to be reminded what an amazing artist John was, one of the very best Australian photographers, his poetic photographs are cosmological in their musicology and composition

~ Two photographs from Paul Knight’s outstanding Cinema curtain series (below). For me there was a textural, sensory experience here, an intimacy with the subject matter that forced me to focus on the surface of the photograph, the flat plane of the photographic print, itself a highly abstract form. Amazing

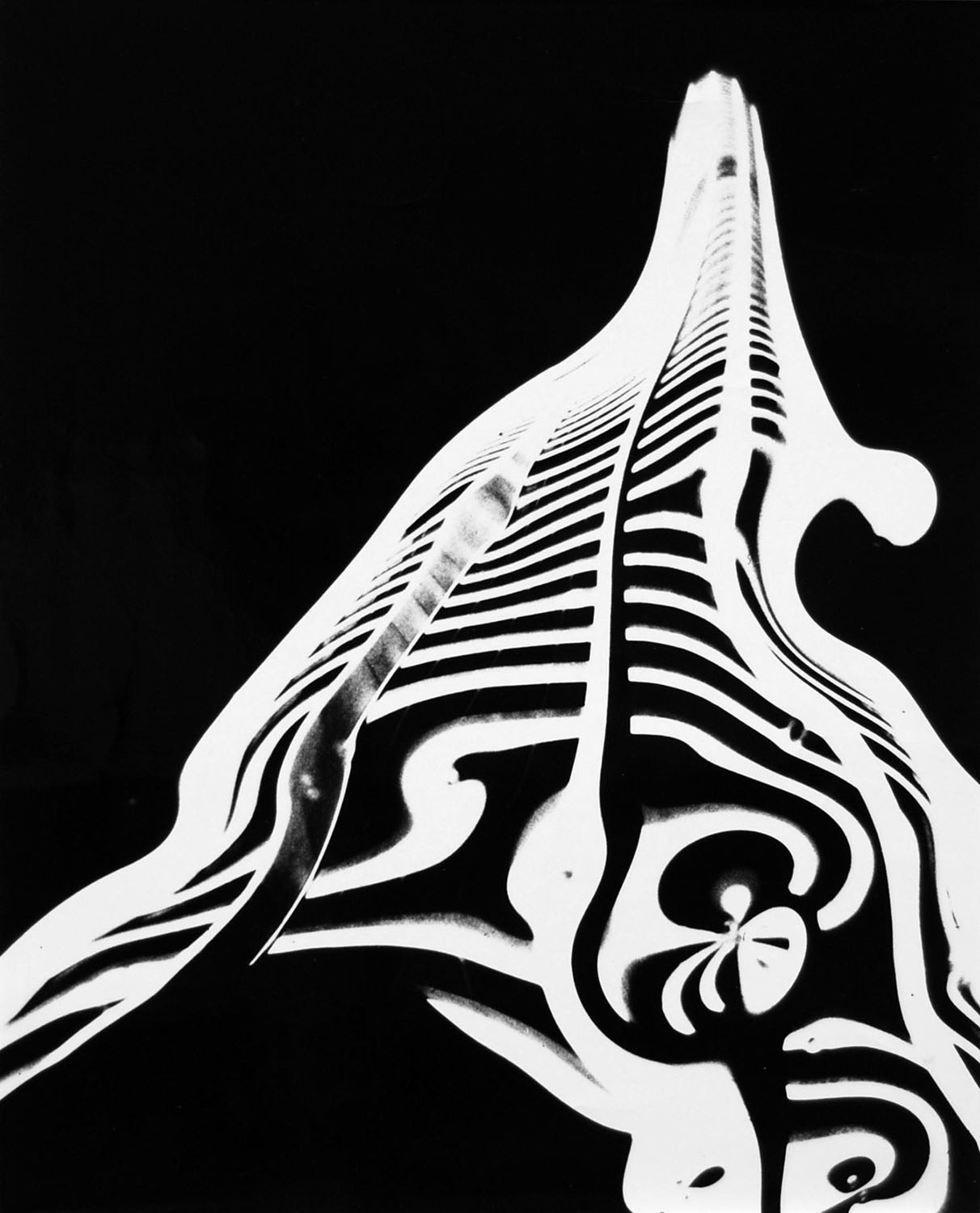

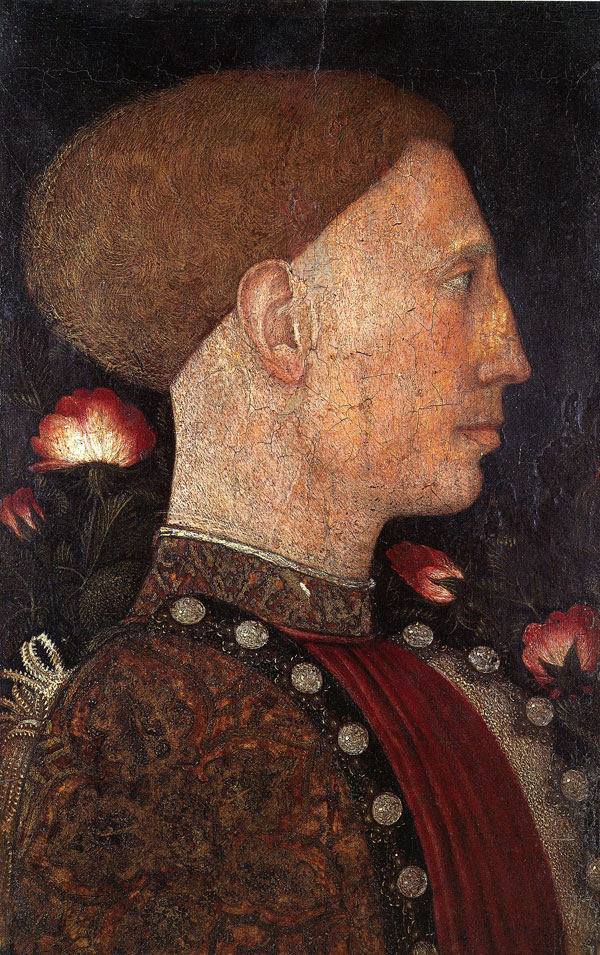

~ My particular favourite in the exhibition were the unknown to me works of the artist Jozef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski (see the two images directly below). These photographs were the most delightful surprise of the exhibition – landscapes of the mind that had great feeling and focus, felt movement, space, flow of light and energy. This was wonderfully nuanced work that I wanted to see more of

Some excellent work then that was let down by two curatorial decisions. The first was the amount of work in the exhibition by each artist – a couple of prints here, another three small prints there – that really never gave the viewer chance to fully engage with the outcomes that the artist was trying to achieve nor explore the process that the artist was using. I know this was a group exhibition trying to highlight work from the collection but a more useful contribution would have been less artist’s in the exhibition with greater work from each, allowing for a more focused exhibition.

Far more serious, however, was the lack of any text that placed the work in a socio-cultural context. At the beginning of the exhibition there was 5 short paragraphs on a wall as you enter the space with mundane insights such as:

~ Photographic language engages the senses and imagination and challenges the way we “look” at the world

~ Through the use of cropping and obscure angle the familiar is made unfamiliar

~ Colour, shape and form (geometric patterns) are important

~ Some artists’ eliminate the camera altogether through photograms, scanner, collage

~ Use of multiple exposures, distortion, mirroring

~ By drilling down into the substances and processes of photography we can reflect on the very nature of photography itself

~ Exploring geometry and patterns found in nature and the built environment or alluding to more intangible themes such as time, mortality and spirituality

I have précised the five paragraphs but that’s all you get!

The only other information comes from brief wall texts accompanying each artist and these sound bites really don’t give any social and cultural context to the artist, the time they lived in or the social themes that would have influenced the work. For example, who would know from this exhibition that the artist John Cato was one of the first photographers in Australia to create visual tone poems using images of the Australian landscape, one of the first to work in sequences of images and who would go on to be a teacher of great repute, helping other emerging photographic artists at a critical time in the development of Australian art photography. Nobody. Also, I wanted to know more about the “substances” and “processes” of photography in regard to photographic abstraction. There was no serious theoretical enquiry, no educational component offered to the viewer here.

While money might be tight there is really no excuse for this lack of creditable, researched, insightful information. You don’t need a catalogue, all you need is a photo-stated 4-6 page essay to be given to visitors (if they desire to have one, if they want the information). It doesn’t take money it takes will to inform and educate the viewer about this important aspect of Australian photographic history. For a subject so engaging this was most disappointing. In this particular case the curators really did drop the abstract ball.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Monash Gallery of Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

John Gollings (Australia, b. 1944)

Untitled

1988

From the series Bushfire aerials

Gelatin silver print

45.5 x 55.0cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the artist

While John Gollings is best known for his work as an architectural photographer, he has produced a number of works that hone in on the Australian landscape. This aerial photograph looks down onto a landscape that has been scorched by bushfire. Viewed from above, without any horizon line to give a sense of scale or orientation to the terrain, this charred topography takes on the appearance of hairy, stubbled skin. Gollings uses this ambiguity to great effect, making the dirt tracks look like wounds that have scarred the surface of the earth, and the effects of smoke and ash look like bruises. In this respect, the use of aerial photography has allowed the images to be read as abstract ciphers of ecological trauma.

Text from the Monash Gallery of Arts website

David Stephenson (born USA 1955 arrived Australia 1982)

Star drawing 1996/402

1996

From the series Star drawings 1995-2006

Chromogenic print, printed 2008

55.8 x 55.8cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the artist, John Buckley Gallery Melbourne, Boutwell Draper Gallery, Sydney and Bett Gallery, Hobart

In a career spanning over 40 years, David Stephenson has consistently used photography to transcend visible reality, photographing built and natural environments to explore abstract, intangible themes such as time, mortality and spirituality. Stephenson made these Star drawings in Central Australia, overlaying as many as 72 different exposures to make one work. For each photograph he used a list of predetermined rules. For instance, he would decide on the length and number of exposures and how far he would rotate his camera between each exposure before embarking on the creation of each image. The images, each of which took a couple of hours to produce, were in this sense pre-planned; however, the amount of variables involved such as the movement of the earth and the stars during each shoot, meant the result always incorporated an element of chance. Interested in the idea that photography is essentially drawing with light, Stephenson’s series of experimental abstract patterns is not so much about documenting the night sky as it is about conceptually exploring the nature of light, time and photography itself.

Text from the Monash Gallery of Arts website

Paul Knight (Australia, b. 1976)

Cinema curtain #3

2004

Chromogenic print

43.5 x 55.0cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the artist

The function of the stage curtain in the cinema was to help suspend the illusion of reality in the moving image of the film. The idea being that the plain white screen behind the curtain was never seen without the moving image on it. So the illusion always existed behind the curtain and was simply masked-off from us by it. This is partly why the image was alway projected onto the curtain for a moment before it was opened, to ensure that we never saw the dead white screen. These works use this function of the cinema stage curtain as a way of engaging with the meta-reality offered by the flat-plane of a photographic print. Utilising the lure of aesthetics and pattern to bring the viewer onto the folded membrane of the curtain and onto the essentially flat plane of the print. Both give way to a potential of volume.

Text from the Paul Knight website [Online] Cited 21/09/2012 no longer available online

Paul Knight (Australia, b. 1976)

Cinema curtain #2

2004

Chromogenic print

43.5 x 55.0cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the artist

Jozef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski (born Poland 1922 arrived Australia 1949 died 1994)

Australia Square – Sydney

1971

From the series Inscape 871

Gelatin silver print

29.4 x 24.0cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the artist

Originally trained as a painter, Jozef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski was interested in the advancement of art materials and techniques. He worked across a variety of media, including painting, sculpture, photography, electronic sound and light projections. He was also interested in combining different art forms and experimented with blending photography with music and sound.

Ostoja-Kotkowski played a key role in the development of experimental photography as well as electronic art in Australia. While his subjects were taken from the real world, they were photographically distorted and abstracted so that many became unrecognisable. He used this technique to create the series Inscape 871, examples of which are exhibited here. Inscape refers to an inner landscape, or images of the mind, while 871 refers to the month and year the works were completed. This series was included in the National Gallery of Victoria’s exhibition Frontiers (1971), which featured five Australian experimental photographers.

Text from the Monash Gallery of Arts website

Jozef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski (born Poland 1922 arrived Australia 1949 died 1994)

Untitled

c. 1971

Gelatin silver print

29.4 x 24.0cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

Donated by Ken Scarlett 2004

© courtesy of the Estate of J S Ostoja-Kotkowski

Anne MacDonald (Australia, b. 1960)

Cloth (red velvet)

2004

Ink-jet print

105 x 70cm

Collection of the artist

© courtesy of the artist and Bett Gallery, Hobart

John Cato (Australian, 1926-2011)

Tree – a journey

1971-1979

From the series Essay I

Gelatin silver print

35.5 x 27.5cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the John Cato Estate

Chantal Faust (Australian, b. 1980)

Waiting

2007

From the series Milk

Chromogenic print

80.0 x 58.0cm

Collection of the artist

© courtesy of the artist

Like much of Chantal Faust’s photographic work, her series Milk was produced using a digital flatbed scanner, a method that allowed her to generate photographs without the use of a camera. The series documents milk being drunk from a bowl and can be linked to the tradition of 1960s and 1970s ‘process art’. During the late 20th century, photography was often employed by artists who wanted to document performance-based art actions and activities. Faust’s ‘action’ of slurping milk from a bowl is a playful extension of this tradition.

Text from the Monash Gallery of Art website

Chantal Faust (Australian, b. 1980)

Lap Milk

2007

From the series Milk

Chromogenic print

80.0 x 58.0cm

Collection of the artist

© courtesy of the artist

Drawing on MGA’s collection of Australian photographs, Photographic abstractions highlights the work of 33 Australian artists who use photography to achieve abstract effects. Ranging from modernist geometric abstraction and the psychedelic experiments and conceptual projects of the 1970s, through to recent explorations of pixelated pictorial space, this exhibition surveys a rich history of abstract Australian art photography. Photography is traditionally recognised for its ability to depict, record and document the world. However, this exhibition sets out to challenge these assumptions. As co-curator of the exhibition and MGA Curator Stephen Zagala states, “The artists in this exhibition are less concerned with documenting the world and more interested in engaging the senses, exciting the imagination and making the ordinary appear extraordinary.”

Some artists have eliminated the camera altogether, preferring the effects that can be achieved with photograms and digital scans. Other artists have experimented with multiple exposures, mirrored images, irregular lenses and the printing of the usually discarded stubs of negatives. Co-curator and MGA Curatorial Assistant Stella Loftus-Hills says, “Photography has always been tied to abstraction. Some of the first photographs ever produced were abstract and subsequent photographers have sought out abstract compositions in their work.”

One highlight of the exhibition is a selection of works by the iconic Australian photographer David Moore, who experimented with abstract photography alongside his more well-known figurative work. In Moore’s Blue collage (1983) the process of cutting bands of colour from existing photographs to create a new composition celebrates the artist’s imagination above and beyond the camera’s ability to capture content.

Artists include Andrew Browne, John Cato, Jo Daniell, John Delacour, Peter Elliston, Joyce Evans, Chantel Faust, Susan Fereday, Anthony Figallo, George Gittoes, John Gollings, Graeme Hare, Melinda Harper, Paul Knight, Peter Lambropoulos, Bruno Leti, Anne MacDonald, David Moore, Grant Mudford, Harry Nankin, Ewa Narkiewicz, John Nixon, Rose Nolan, Jozef Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski, Robert Owen, Wes Placek, Susan Purdy, Scott Redford, Jacky Redgate, Wolfgang Sievers, David Stephenson, Mark Strizic and Rick Wood.

Press release from the MGA website

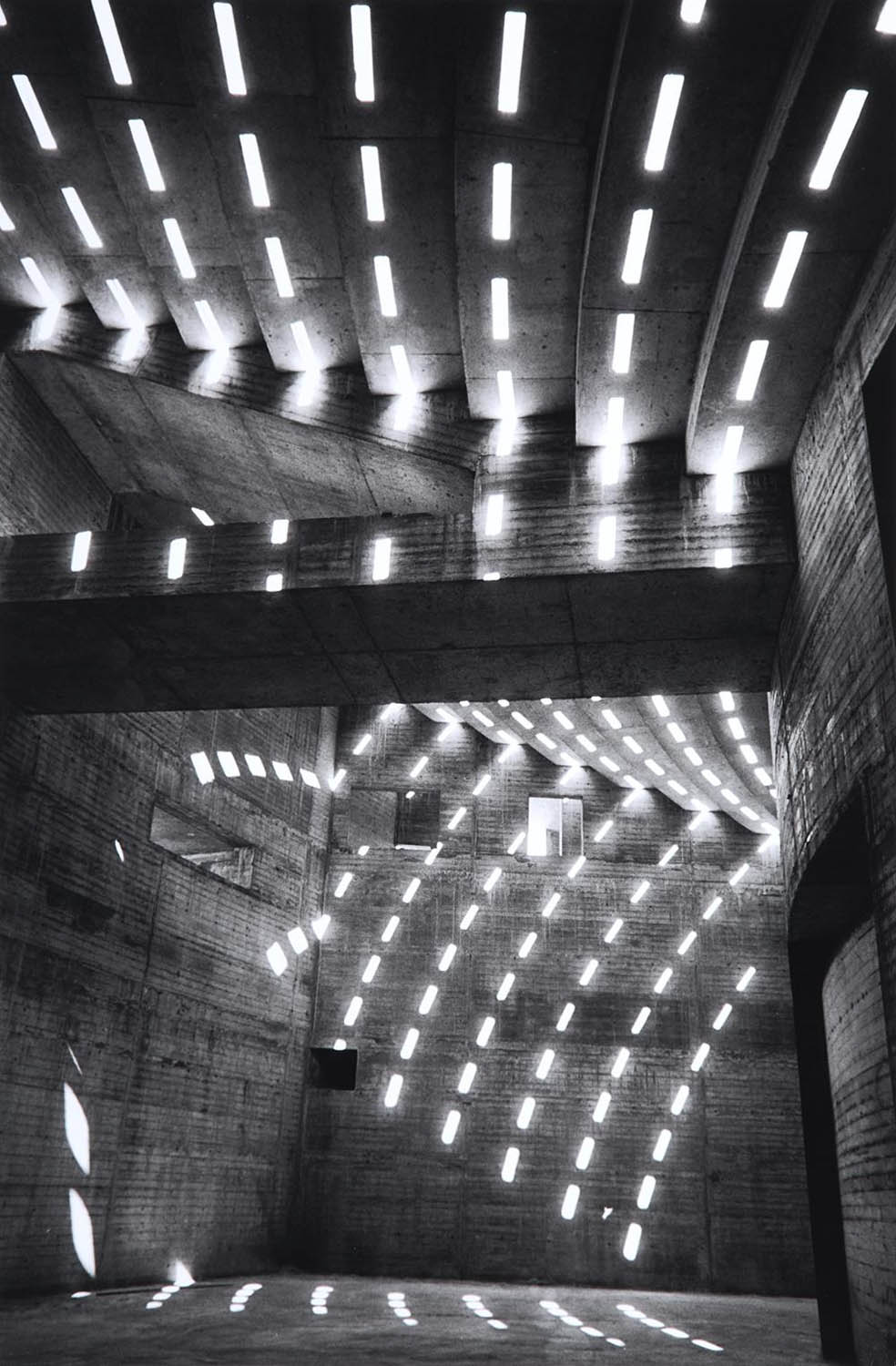

David Moore (Australian, 1927-2003)

Sun patterns within the Sydney Opera House

1962

Gelatin silver print, printed 2005

37.75 x 25.0cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the Estate of David Moore

David Moore (Australian, 1927-2003)

Sisters of Charity, Washington DC

1956

Gelatin silver print

30.5 x 19.5cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the Estate of David Moore

Robert Owen (Australian, b. 1937)

Street, Burano, Italy

1978

Silver dye bleach print

20 x 25cm

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the artist and Arc One Gallery, Melbourne

Robert Owen (Australian, b. 1937)

Green Sheet, Burano, Italy

1978

Silver dye bleach print

Monash Gallery of Art, City of Monash Collection

© courtesy of the artist and Arc One Gallery, Melbourne

Scott Redford (Australian, b. 1962)

Urinal (Broadbeach)

2000-2001

From the Urinals series 1988-2001

Chromogenic print

Collection of the artist

© courtesy of the artist

Scott Redford (Australian, b. 1962)

Urinal (Surfer’s Paradise)

2000-2001

From the Urinals series 1988-2001

Chromogenic print

Collection of the artist

© courtesy of the artist

Scott Redford (Australian, b. 1962)

Urinal (Fortitude Valley)

2000-2001

From the Urinals series 1988-2001

Chromogenic print

Collection of the artist

© courtesy of the artist

Redford’s photographs of urinals… dialogue with art historical motifs that precede discourses of minimal art and postmodern understandings of the abject. In representing the site of male urination, they evoke the oxidation paintings of Andy Warhol, who directed young men to piss onto canvases prepared with copper oxide, resulting in compelling abstract imagery… All of that is in Redford’s photographs and at the same time they are completely empty and quiet and contemplative… They are pure sensory experience like rainfall, even transcendent in their purity. They are concerned with beauty, but they are beyond debates about beauty. They are indifferent and in this they are transcendent.

Chapman, Christopher. “Scott Redford’s urinals,” in Redford, Scott et.al. Bricks are Heavy (exhibition catalogue). Brisbane: Institute of Modern Art, pp. 6-7.

Monash Gallery of Art

860 Ferntree Gully Road, Wheelers Hill

Victoria 3150 Australia

Phone: +61 3 8544 0500

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 10am – 5pm

Saturday – Sunday 10am – 4pm

Mon/public holidays: closed

You must be logged in to post a comment.