Exhibition dates: 2nd June – 29th July 2012

Apologies, just a short review as I have been sick all weekend. It’s hard to think straight with a thumping headache…

~ An interesting exhibition with several strong elements

~ Wonderful use of the ACCA space. Nice to see the building allowed to speak along with the work; in other words a minimal install that shows off the work and the building to advantage. ACCA could do more of this.

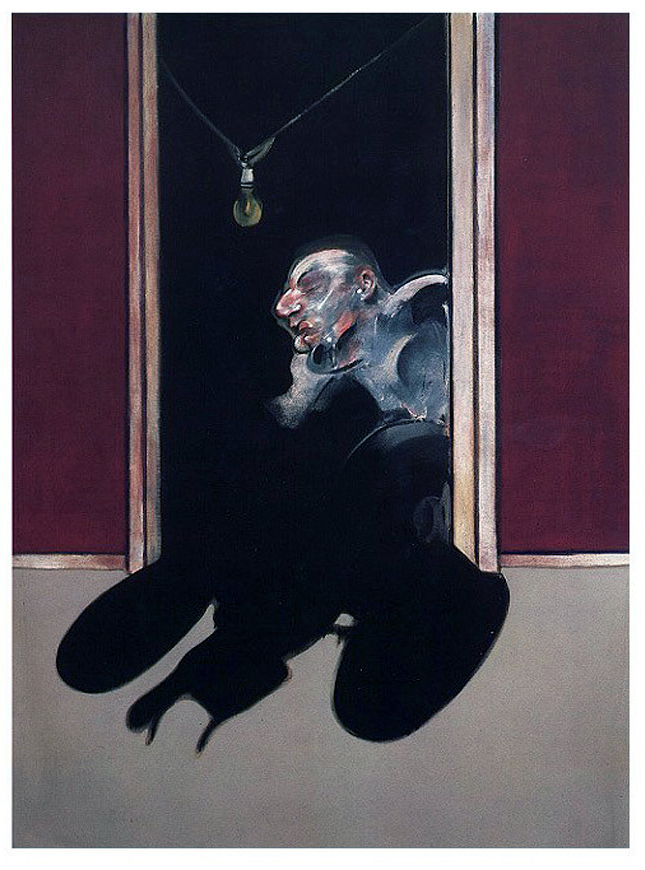

~ The main work We Are All Flesh (2012, below) reminded me of a version of the game The Hanged Man (you know, the one where you have to guess the letters of a word and if you don’t get the letter, the scaffold and the hanged man are drawn). The larger of the two hanging pieces featured two horse skins of different colours intertwined like a ying yang paux de deux. Psychologically the energy was very heavy. The use of straps to suspend the horses was inspired. Memories of Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp and The Godfather rose to the surface…

~ I found it difficult to get past the fact that the sculptures were built on an armature with epoxy = the construction of these objects, this simulacra, had to be put to the back of my mind but was still there

~ Inside me III (2012, below) was a strong work reminding me of an exposed spinal column being supported by thin rope and fragile trestles. Excellent

~ The series of work Romeu “my deer” (2012, below) was the least strong in the exhibition. Resembling antler horns or the blood vessels of the aorta bound together with futon like wadding, the repetition of form simply emphasised the weakness of the conceptual idea

~ My favourite piece was 019 (2007, below). Elegant in its simplicity this beautiful display case from a museum was dismantled and shipped over to Australia in parts and then reassembled here. The figurative pieces of wood, made of wax, seemed like bodies drained of blood displayed as specimens. The blankets underneath added an element of comfort. The whole piece was restrained and beautifully balanced. Joseph Beuys would have been very proud!

~ The “visceral gothic” contained in the exhibition was very evident. I liked the artist’s trembling and shuddering. Her narratives aroused a frisson, a moment of intense danger and excitement, the sudden terror of the risen animal

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“On one hand, I shoot disconcerting questions at the spectator, to which I do not give any re-assuring answers; on the other hand, the presence of human characteristics in my figures is familiar, and therefore comforting.”

“Life is beautiful even if we have to deal with fear and pain… It makes it easier if we take care of each other and if we have a language with each other to communicate about pain, suffering and fear.”

“That’s what makes a good sculpture, I think: the fact it doesn’t rely on a meaning or subject matter, but that it is so broad that you can take it in any number of different directions, and lose your way in it.”

Berlinde De Bruyckere

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

We Are All Flesh (installation view)

2012

Treated horse skin, epoxy, iron armature

280 x 160 x 100cm

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galleria Continua

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

We Are All Flesh (installation view)

2012

Treated horse skin, epoxy, iron armature

280 x 160 x 100cm

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galleria Continua

Photo: Andrew Curtis

“I only use animals in a human way. I started to work on horses in 1999, when the Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres asked me to reflect on war today. I was working more than one year in their archives and did a lot of research on this matter. The most important images for me were the abandoned city and the dead bodies of the horses. These images were staying with me. I took the motif of the dead horse as a symbol for loss in war, wherever it happens. Because if we address war, it’s about losing people. I wanted to translate that feeling so I started to work on six portraits of dead horses. Some years afterwards when people were asking about other animals in my work, I said ‘no’. I need the horse because of its beauty and its importance to us. It has a mind, a character and a soul. It is closest to us human beings. I couldn’t imagine another animal being so important.”

Berlinde De Bruyckere, 2011

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

We Are All Flesh (installation view detail)

2012

Treated horse skin, epoxy, iron armature

280 x 160 x 100cm

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galleria Continua

Berlinde De Bruyckere uses wax, wood, wool, horse skin and hair to make haunting sculptures of humans, animals and trees in metamorphosis.

Based in her home town of Ghent, Berlinde De Bruyckere’s studio is an old neo-Gothic Catholic school house. From here she creates her incredible sculptures – torsos morph into branches, trees are captured and displayed inside old museum cabinets and cast horses are crucified upside down in works that have been described as brutal, challenging, inspiring and both frightening and comforting.

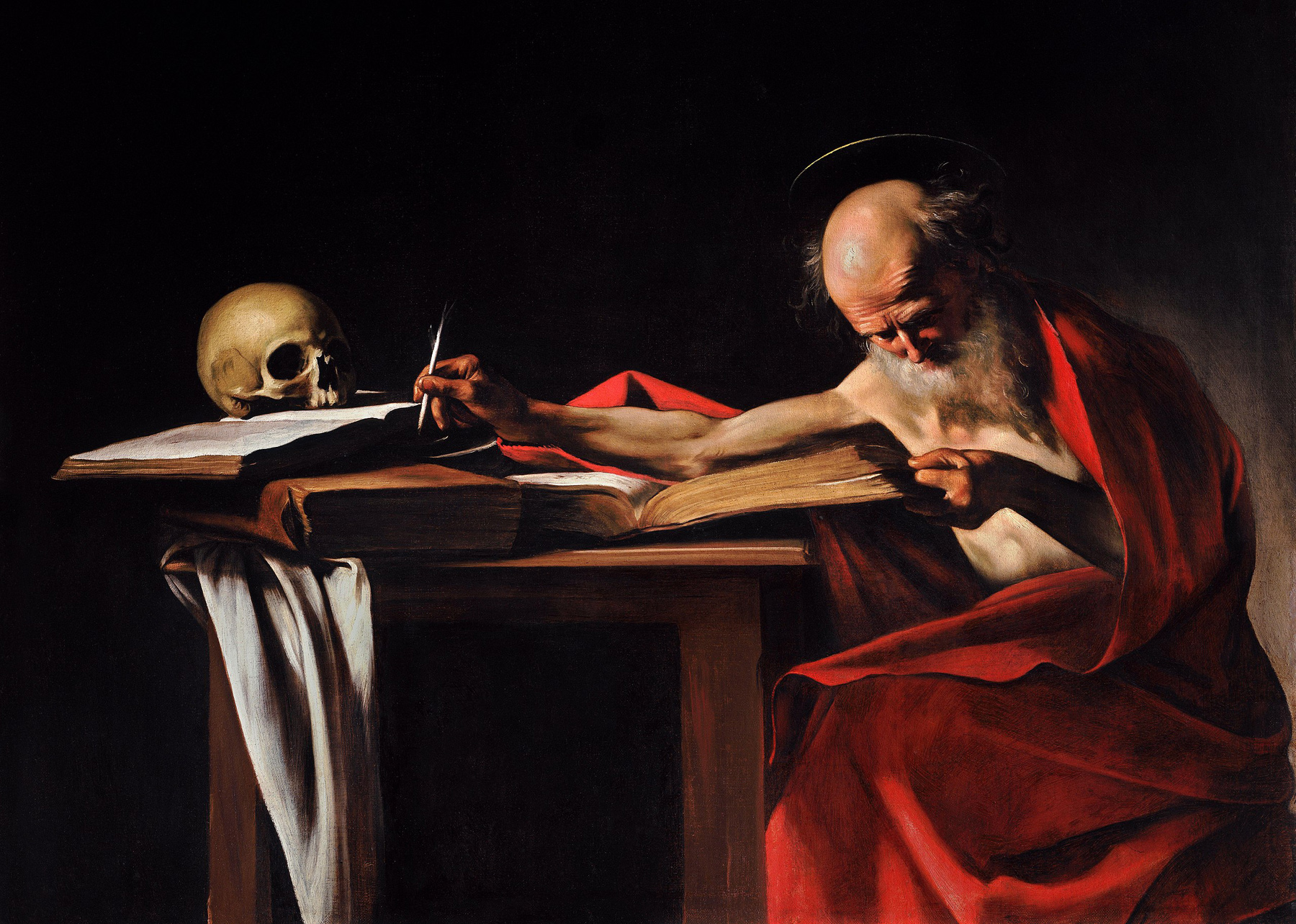

Heavily influenced by the old masters, De Bruyckere’s early years at boarding school were spent hiding in the library, pouring over books on the history of catholic art. She went on to study at the Saint-Lucas Visual Arts School in Ghent, and was known in the early stages of her career for using old woollen blankets in her works, sometimes simply stacked on tables of beds, a response to news footage she had seen of blanket-swathed refugees in Rwanda.

Her breakthrough work In Flanders Fields, five life-size splay-legged horses captured in the throes of death, was commissioned by the In Flanders Fields Museum, in the town of Ypres, the site of the legendary World War 1 battle. She was then invited to participate in the 2003 Venice Biennale, and the subsequent work, an equine form curled up on a table titled Black Horse, firmly established her on the international scene. She has since had solo exhibitions at Hauser & Wirth in Zurich and New York and in prestigious museums across Europe.

“Berlinde De Bruyckere creates works that recall the visceral gothic of Flemish trecento art, updated to a new consideration of the human condition,” says Juliana Engberg, ACCA Artistic Director.

“Her work taps into our human need to experience transformation and transcendence, to experience great depths of feeling transferred from the animal to human. Through experiencing Berlinde’s amazing sculptural works we come closer to the human condition and the tragedy and drama of mortality, out of which something miraculous occurs in metamorphosis.”

We are all Flesh will include the rarely seen and iconic work 019 and two new commissions created specially for this exhibition.

Text from the ACCA website

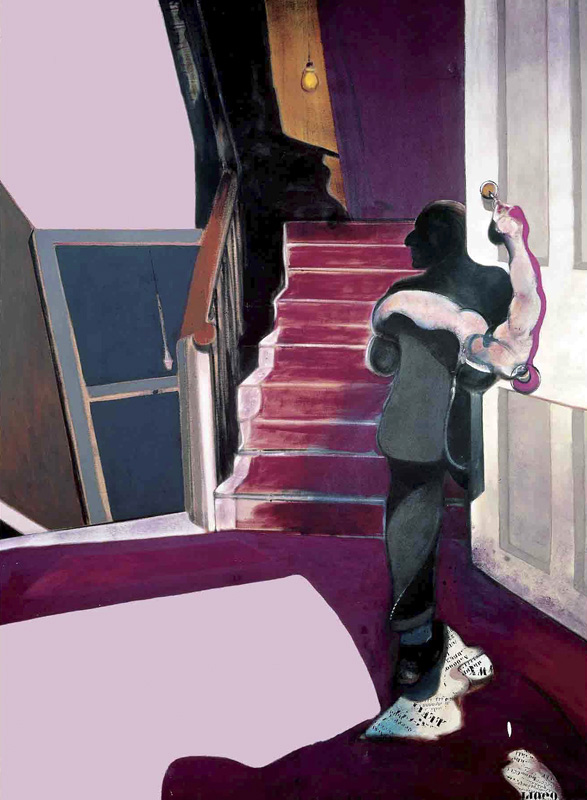

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

019 (installation view)

2007

Wax, epoxy, metal, glass, wood, blankets

293.5 x 517 x 77.5cm

Private Collection, Paris

Photo: Andrew Curtis

“Behind the distorted, antique glass, you see sculptures in the shape of trees or branches. The trees are nearly the colour of human skin, so you end up with something fragile. Because the antique glass distorts your view, a couple of doors are left open, inviting you to look inside. I don’t want people to see the sculptures as trees, but as strange, vulnerable beings. The vitrines have a shelf at the bottom on which I placed three piles of blankets. It looks as if they are shielding and nurturing the roots of the trees… I also refer to those blankets as a “soothing circumstance” because they can sometimes lead us to a less harsh reality.”

Berlinde De Bruyckere

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

019 (installation view)

2007

Wax, epoxy, metal, glass, wood, blankets

293.5 x 517 x 77.5cm

Private Collection, Paris

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

019 (installation view detail)

2007

Wax, epoxy, metal, glass, wood, blankets

293.5 x 517 x 77.5cm

Private Collection, Paris

What is the Meaning of Trecento (1300-1400)

The term “trecento” (Italian for ‘three hundred’) is short for “milletrecento” (‘thirteen hundred’), meaning the fourteenth century. A highly creative period, it witnessed the emergence of Pre-Renaissance Painting, as well as sculpture and architecture during the period 1300-1400. In fact, since the trecento coincides with the Pre-Renaissance movement, the term is often used as a synonym for Proto-Renaissance art – that is, the bridge between Medieval Gothic art and the Early Renaissance. The following century (1400-1500) is known as the quattrocento, and the one after that (1500-1600) is known as the cinquecento.

The main types of art practised during the trecento period showed relatively little change from Romanesque times. They included: fresco painting, tempera panel painting, book-painting or illuminated manuscripts, metalwork, relief sculpture, goldsmithery and mosaics.

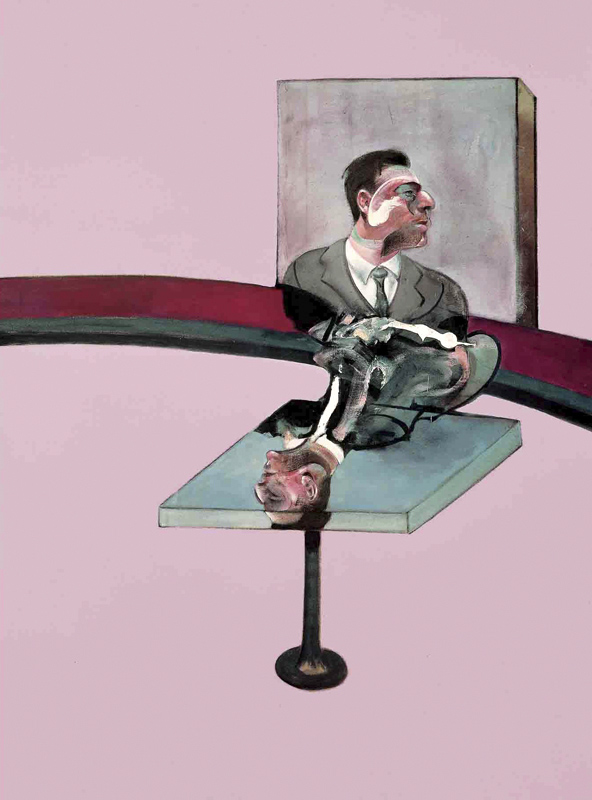

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

Inside me III (installation view)

2012

Wax, wool, cotton, wood, epoxy, iron armature

135 x 235 x 115cm

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galleria Continua

Created especially for ACCA, Inside Me III is a tangle of flesh-coloured wax branches reminiscent of intestines, tree roots and human limbs, splayed across worn white pillows and slung between a frame based on a drying rack for herbs. This is a body turned inside out shown as a bag of bones and flesh. It’s a body reduced to its most basic form. In this state the viewer is encouraged to think about what makes us human. Yes we are all flesh – but we are more than the physical, aren’t we? Inside Me alludes to an interior state of being, a tangle of intangible emotions and feelings that are very real. Similar to the work in Gallery 4, here human limbs become branches, as tree trunks stand in for people in 019, reminding us of a universal life cycle, and for De Bruyckere ‘life and hope’.

Text from the Berlinde De Bruyckere We Are All Flesh ACCA Education Kit

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

Inside me III (installation view)

2012

Wax, wool, cotton, wood, epoxy, iron armature

135 x 235 x 115cm

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galleria Continua

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

The Pillow (installation view)

2010

Wax, epoxy, iron, wool, cotton, wood

90 x 70 x 60cm

Private Collection, Brussels

To one side of the room a wax figure is crouched over a soft pillow, the body hairless, faceless and surface almost transparent. ‘The Pillow’ is another important loan in the exhibition and the only obviously human figurative element. The figure appears to be protecting itself, curled inwards into a pillow atop a small wooden box. The fragility and rawness of the body is softened by the use of pillows. Here the pillow supports the figure as a sort of plinth, comforting the body. Four antler-based works are suspended by strings from the gallery wall. Unlike the clichéd hunting trophies mounted in baronial halls, these antlers are pallid, delicate and raw. Antlers are a more recent motif for De Bruyckere. In Metamorphoses, Ovid retells the Greek myth of Actaeon, who accidentally stumbled across the Goddess Diana bathing. In an embarrassed fury she transforms Actaeon into a stag. He is unable to speak and flees in fear. His fellow hunters and their dogs do not recognise him and he is torn to death by his own hounds. The male deer’s antlers serve to seduce the female but also to test their strength with other males and defend themselves against predators. In this sense they are also capable of destruction. The antler grows out of the body without control, and in some of De Bruyckere’s drawings they grow back inside it, suggesting that sometimes our strongest weapons can, despite their benefits, also be a threat to our own lives. Not only referencing mythology, the stag is also a traditional symbol of Christ. De Bruyckere has frequently used the Man of Sorrows motif, which throughout history has shown Christ, usually on the cross with the wounds of the passion, Here its interpretation enhances our sympathy for the hunted animal as well.

Text from the Berlinde De Bruyckere We Are All Flesh ACCA Education Kit

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

Romeu “my deer” (installation view)

2012

Pencil, watercolour, collage

37.5 x 28cm

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galleria Continua

Berlinde De Bruyckere (Belgian, b. 1964)

Romeu “my deer” (installation view detail)

2012

Pencil, watercolour, collage

37.5 x 28cm

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Galleria Continua

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA)

111 Sturt Street

Southbank

Victoria 3006

Australia

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 10am – 5pm

Saturday – Sunday 11am – 5pm

Monday closed

Open all public holidays except Christmas Day and Good Friday

You must be logged in to post a comment.