Exhibition dates: 26th August – 31st December 2023

Curatorium: Leo Schofield AM (curatorium chair), Ronan Sulich (advisor), Mark Sutcliffe (advisor) and Eva Czernis-Ryl (Powerhouse)

Assistant curator: Chloe Appleby (Powerhouse)

Exhibition manager: Anna Gardner (Powerhouse)

Exhibition coordinator: Kerrie Goodwin (Powerhouse)

Exhibition designers: Pip Runciman, Julie Lynch and Ross Wallace

Lighting Designer: Damien Cooper

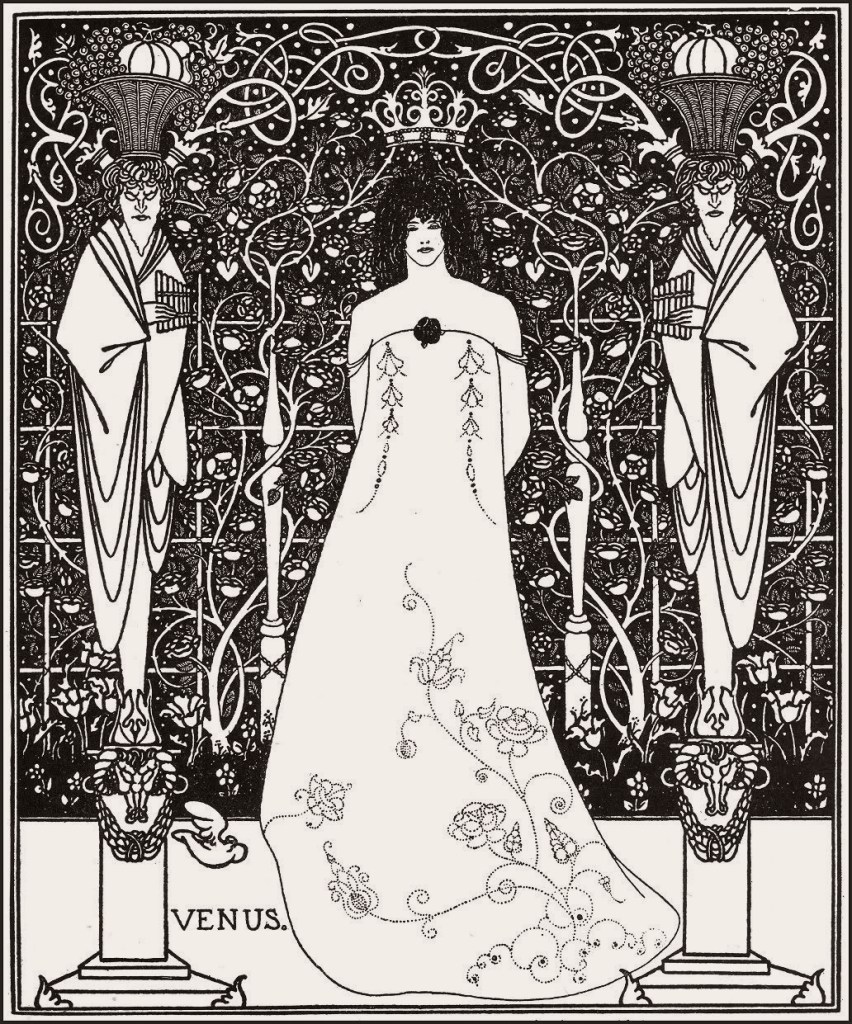

Wedgwood & Bentley (English, manufacturer)

Venus

Early 1800s

Black basalt, stoneware

Height: 350 mm

Width: 210 mm

Depth: 150 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1949

Many rooms of wonder

What a visual feast we have for you this week!

Being an inveterate collector of eclectic objects who then puts them together in disparate but sympathetic arrangements (as in a Wunderkammer or ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’), the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney was a natural for me to post on.

“… the idea of a Wunderkammer was fully born in the sixteenth century as the princely courts of Europe became less peripatetic and as humanist philosophy spread. It was no longer enough simply to show off one’s wealth; every object should also enhance the virtues of the prince. In Inscriptiones vel tituli theatre amplissimi (1565), Samuel Quiccheberg detailed the ideal formula for the Wunderkammer as including naturalia (items created by the earth and items drawn from nature), mirabilia (unusual natural phenomena), artificialia (items wrought by man), ethnographica (items from the wider world), scientifica (items that brought a great understanding of the universe) and artefacta (items relating to history). Together these works would bring the wider world into the court and provide an understanding of the entire universe.”1

While Wunderkammer were the playthings of princes they brought to wider attention the miracles of the universe both natural and manmade. They made human beings aware of the enormity of the forces of nature and (human) industry that surrounded them … through the history and memory of objects.

John McDonald observes every piece has a story. But it is only through (in my case as a collector) being in the presence of these objects and physically handling them that we begin to understand the difference between one piece of Chinese bronze and another, one from the Ming dynasty and another from the Qing dynasty… and the difference in feeling between the two in terms of quality, casting, detail, aesthetics, form. Only through the physical handling of objects do we begin to understand the difference between an original and a fake, how old they are, how they were constructed, what their patina means, and what aura and power the object possesses. I have several pieces of treen (carved wood) in my collection and through the act of holding these objects I wonder about their history. The process is as much a tactile experience as it is a visual one.

The exhibition curators know their art. It is with great pleasure that I observe in an installation photograph in this posting the conflation of two objects that form what Minor White would call “ice/fire” where two disparate objects play off of each other: in this case a vase by that most famous and radical 19th century British designer Sir Christopher Dresser paired with a plate by the equally radical 20th century Russian designer El Lissitzky. A match made in heaven that plays out across the decades, repeated in numerous quirky juxtapositions and inspired nexus throughout the exhibition.

What further sets this exhibition off for me if the absolutely gorgeous and sympathetic “theatrical environments for these whimsical-but-rational groupings.” Exhibition designers Pip Runciman, Julie Lynch and Ross Wallace evoke a visually ravishing atmosphere in which the exhibition flâneur/flâneuse can stroll and take in the sights. Compare this stunning installation to the execrable rooting of the June 2023 Melbourne Winter Masterpieces exhibition Pierre Bonnard at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne which presented the iridescent paintings of Bonnard within immersive scenography by Paris-based designer India Mahdavi. Here the work of Pierre Bonnard (which was supposed to be the subject of the exhibition not its addendum) was almost completely overwhelmed by the manic graphic design background of the installation. “Immersive scenography” = art speak for a load of no/sense.

Let the objects speak to us directly or not at all.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Anonymous. “Wunderkammer: Cabinet of Curiosities,” on the Royal Collection Trust website Nd [Online] Cited 01/12/2023

Many thankx to the Powerhouse Ultimo for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

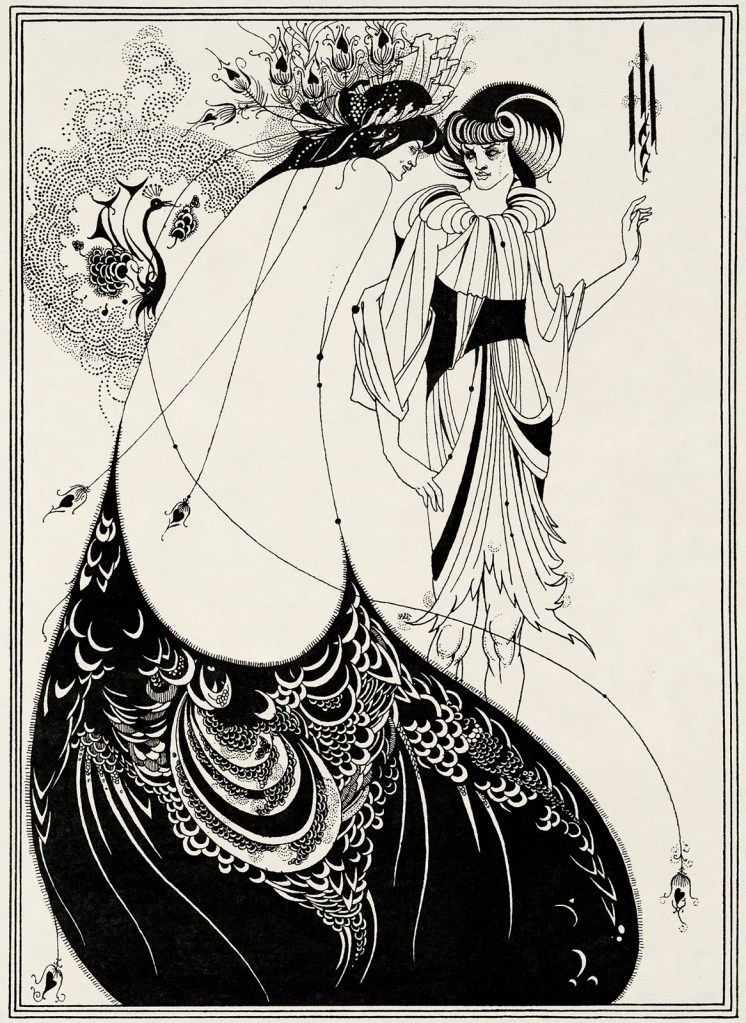

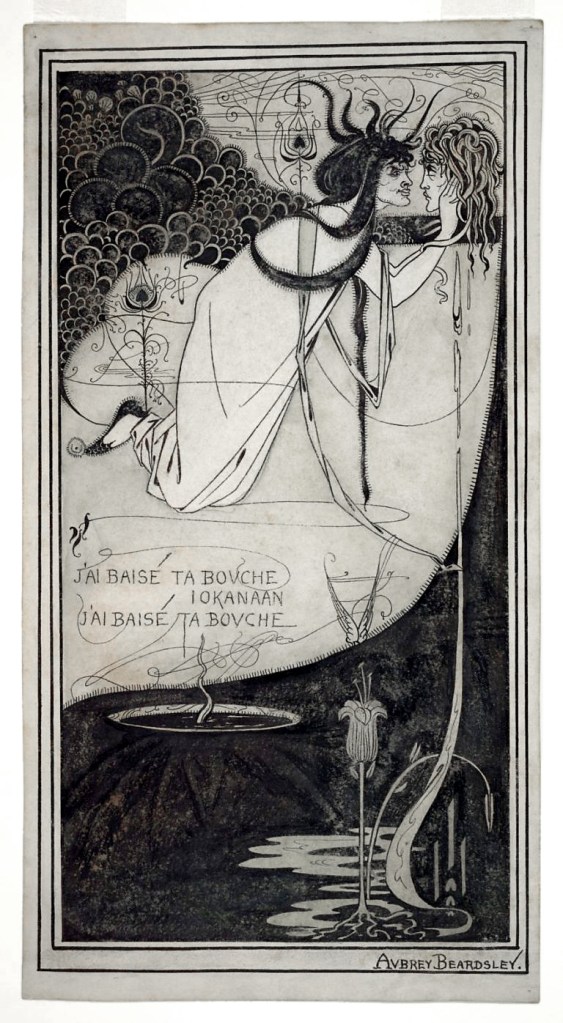

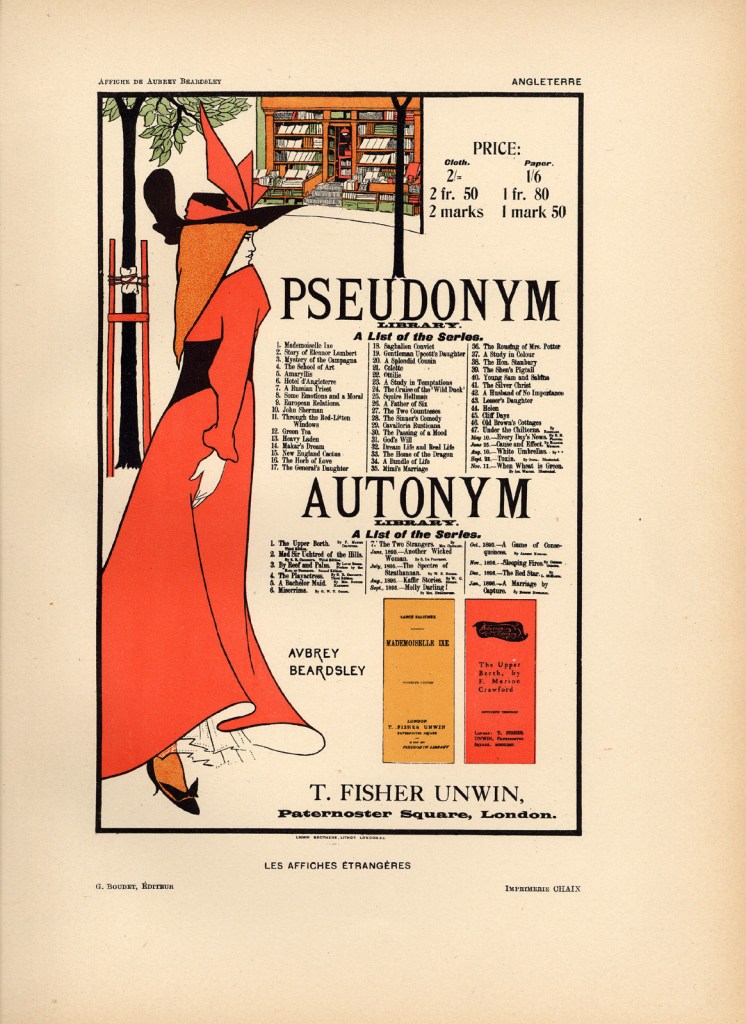

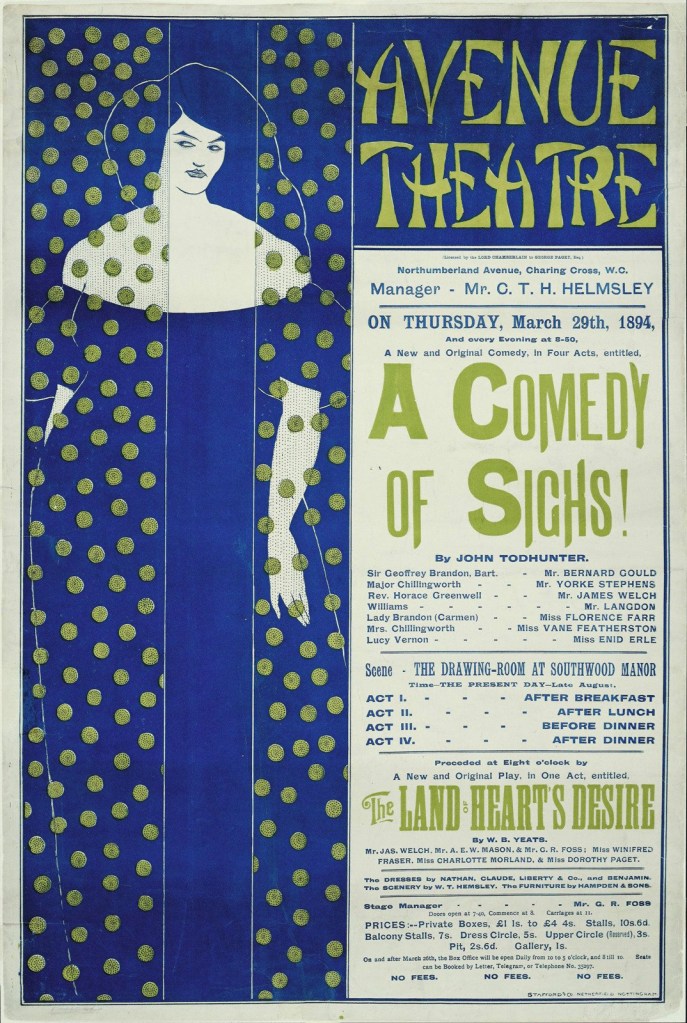

“Every piece in this show has a story, but they are best sampled first-hand. Curatorially, 1,001 Remarkable Objects is a cultural pot-pourri, with disparate items clustered together based on a shared motif or theme. In some rooms, it’s as if Schofield, along with Mark Sutcliffe, Ronan Sulich and Eva Czernis-Ryl, simply put a word such as “peacock” or “music” into the collection database and selected the strangest things that popped up.

Ephemeral items of pop culture are juxtaposed with artefacts of ancient civilisations, tiny pieces of jewellery are linked with great clunking pieces of furniture. Viewers see everything from an Arnott’s biscuit to an electric car manufactured in Detroit in 1917. One extraordinary pairing puts a medieval suit of armour alongside the wheel of the plane in which Charles Kingsford-Smith perished when he crashed in November 1935.

The effect is almost hallucinogenic, and here one needs to give credit to exhibition designers Pip Runciman, Julie Lynch and Ross Wallace, who have created appropriately theatrical environments for these whimsical-but-rational groupings.

This approach, so contrary to the usual curatorial processes, harks back to the ancestor of the modern museum: the Wunderkammer, or cabinet of curiosities, in which royal courts and wealthy connoisseurs in the 17th and 18th centuries would display historical treasures, works of art, items of natural history and ingenious mechanisms.

John McDonald. “An irresistible, mind-boggling exhibition awakens sense of wonder,” on The Sydney Morning Herald website November 11, 2023 [Online] Cited 12/11/2023

Johann Joachim Kändler (modeller)

Royal Saxon Porcelain Manufactory (manufacturer, Meissen, Germany)

Portrait bust, ‘Baron Schmiedel’

1739

Hard-paste porcelain

Height: 475 mm

Width: 360 mm

Depth: 260 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1951

Baron Schmiedel bust by Joachim Kändler

The satirical portrait bust of the court jester Johann Gottfried Tuscheer (born as Johann Gottfried Graf), better known as Baron Schmiedel or Postmaster Schmiedel, was one of the last royal commissions for the Japanese Palace of Augustus the Strong, King of Poland (ruled 1694-1733) and Elector of Saxony. The Japanese Palace was a lavish structure in Dresden refurbished to house both the fabulous royal collection of East Asian porcelains and the amazing new products of the Royal Saxon Porcelain Manufactory in Meissen near Dresden in Germany. Established in 1710, following re-discovery of secret Chinese porcelain formula by the King’s imprisoned alchemist Johann Joachim Böttger, Meissen was Europe’s first factory to make true or hard-paste porcelain. By the mid 1730s, the factory had been able to make monumental animal sculptures, apostle figures and even architectural elements alongside their exquisitely painted vases and tableware.

The bust was modelled by Johann Joachim Kändler (1706-75), the court ‘Modellmeister’ (master modeller) who worked at the Meissen manufactory from 1731 until his death in 1775. The bust was ordered by Augustus III, Augustus the Strong’s son and successor. The medallion on Schmiedel’s chest is based on one of Augustus’ coronation medals.

A highly talented individual who delighted in dressing in the latest fashions, Schmiedel was one of two most prominent jesters at the Saxon court at the time. His role as a jester involved attending the kings in their dressing rooms, at dinners and even at the most intimate court gatherings. He kept company with the kings on visits and hunting expeditions, always ready to crack a joke, exchange witty badinage or play magic tricks with mice while pretending to have morbid fear of rodents. Schmiedel was rewarded with numerous ‘titles’ and valuable presents including Meissen porcelain.

The Schmiedel bust was discovered in Sydney in 1949 by the noted Sydney antique dealer William Bradshaw at a time when its importance and history had been long forgotten. It was acquired by the Museum in 1951. One of the most important objects in the Powerhouse Museum’s collection of ceramics, it is one of only four surviving the the world.

Eva Czernis-Ryl, Curator

For full story see: E. Czernis-Ryl, ‘The golden years of Meissen porcelain and Saxon jesters: the Schmiedel bust in Australia’, Keramik-Freunde der Schweiz (Bulletin des Amis Suisses de la Ceramique), Mitteilungsblatt nr 104, October 1989, pp. 5-11

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at top, El Lissitzky’s Plate (c. 1923, below); and at bottom, Christopher Dresser’s Vase (c. 1888, below)

Lazar Markovich Lissitzky (El Lissitzky, Russian, 1890-1941)(designer and maker, Germany)

Plate (installation view)

c. 1923

Unglazed, earthenware

Depth: 26 mm

Diameter: 190 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 2002

Plate by Lazar Markovich Lissitzky

A round plate made of heavy unglazed earthenware. Decorated in red enamel, sprayed in a stencil like manner (schablonendecor), with geometric motifs along the rim. Three red circles of differing sizes decorate one side of the plate. Two red curved rectangular bands, one short and one long, decorate the other side of the plate. The text ‘Z 2864’ is impressed on the base of the plate.

An architect and graphic designer, El Lissitzky (1890-1941) was among the most important Russian artists to influence Modernism and one of the great avant-garde figures of the 20th century.

His lifetime involvement with abstract art began in 1919 soon after he met the Suprematist artist Kazimir Malevich (see the ‘Design’ section for a summary of his artistic development and achievements). Between December 1921 and January 1924 he lived and worked in Germany and in 1924 was being treated for tuberculosis in Switzerland. Although initially reluctant to apply his distinctive pictorial vocabulary to utilitarian objects, it is during that time that his abstract pictures known as Prouns began to inform Lissitzky’s designs for a group of ceramics. Soon Prouns were also to become the source of his typography, photography and book, furniture and poster design.

This boldly coloured plate is one of the relatively rare examples of Lissitzky’s ceramics. Examples of plates for the same series comprising plates of different sizes can be found in the Sammlung Ludewig in Berlin, National Museum in Nuremberg, Deutsches Museum in Munich, Australian National Gallery in Canberra and in other collections.

Eva Czernis-Ryl, Curator, 2003

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Christopher Dresser (designer, British, 1834-1906)

Linthorpe Pottery (manufacturer, Middlesbrough, Yorkshire, England)

Vase (installation view)

c. 1888

Earthenware

Powerhouse Collection

Gift of Bob Meyer under the Tax Incentives for the Arts Scheme, 1997

As opposed to John Ruskin and William Morris, Christopher Dresser was an enthusiastic advocate of scientific progress and the machine. The association of simplicity with progress led him to reject the taste for rich decoration of 19th century historical styles and Naturalism which used representational decoration and high-relief ornaments indiscriminately applied to objects. Dresser’s interest in forms based on the structure of plants, his emphasis on function in design and the economic use of materials such as electroplated silver, have no precedent in Western design traditions.The restrained design of this striking vase is a fine example of Dresser’s innovative pottery produced by the Linthrope Pottery.

Eva Czernis-Ryl. Curator

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Carlo Scarpa for VSM Paolo Venini & Co (Murano, Venice, Italy)

Carlo Scarpa (designer, Italian, 1906-1978)

Bowl

c. 1940

Murrine opache

Height: 60 mm

Width: 232 mm

Depth: 365 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1984

Before Carlo Scarpa began designing some of Italy’s most celebrated modernist buildings, he spent 15 years with Venini, pushing the boundaries of Venetian glassblowing techniques. He worked for Venini between 1932 and 1947, both pioneering new techniques and reviving traditional Veentian techniques. Franco Deboni, observes: ‘Scarpa’s glass was so radical and innovative for its time. You can see it in the colours, shapes, textures and quality of execution…When you start to analyse the glass, you also realise how extremely complex it was for the master blowers to execute.’ Many of Scarpa’s designs reinterpreted historical designs using modern methods. His murrine romane combined the traditionally round murrina patterns with the square tiles of Roman mosaics. Revealed at the XXII Venice Biennale of 1940, the Murrine Opache technique is amongst the architect’s greatest technical and stylistic achievements.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at top left, Bowl, murrine opache, Carlo Scarpa for VSM Paolo Venini & Co, Murano, Venice, Italy, c. 1940; at top centre, Bowl form, Untitled, kiln formed fused mosaic glass, designed and made by Klaus Moje, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia, 1990-1991; at top right, Vase, blown glass with cane inclusions, Lino Tagliapietra, Rozelle, New South Wales, Australia, 1997; and at centre back, Textile length, Mohnkopfe (poppy heads), silk-double weave, Art Nouveau style, woven by Johann Backhausen and Sohne, Vienna, Austria, made by Koloman Moser, Vienna, Austria, 1900-1903

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at top left, Bowl, murrine opache, Carlo Scarpa for VSM Paolo Venini & Co, Murano, Venice, Italy, c. 1940; at top centre, Bowl form, Untitled, kiln formed fused mosaic glass, designed and made by Klaus Moje, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia, 1990-1991; at top right, Vase, blown glass with cane inclusions, Lino Tagliapietra, Rozelle, New South Wales, Australia, 1997; and at centre back, Textile length, Mohnkopfe (poppy heads), silk-double weave, Art Nouveau style, woven by Johann Backhausen and Sohne, Vienna, Austria, made by Koloman Moser, Vienna, Austria, 1900-1903

Klaus Moje (Australian born Germany, 1936-2016) (designer and maker, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia)

Bowl form, Untitled

1990-1991

Kiln formed fused mosaic glass

Height: 75 mm

Diameter: 540 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1991

Fused Mosaic Glass Bowl by Klaus Moje

This bowl form, ‘Untitled’, was made from fused mosaic Bullseye glass, in Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia, 1990-1991.

Klaus Moje (1936-2016, born Hamburg, Germany) was one of Australia’s most significant glass artists, and also one of the most influential through his teaching in Canberra for 10 years from 1982. His international connections provided many exhibiting and teaching opportunities for others.

The Bullseye Glass Company had been set up in Portland, Oregon, in 1974 by three young glassblowers, Daniel Schwoerer, Boyce Lundstrom and Ray Ahlgren. Schwoerer had also studied glass as graduate assistant to Harvey Littleton at the University of Wisconsin in the 1960s as well as doing graduate work in engineering. Although they were glass blowers, they wanted to support their art through an income-generating industry and saw a need for a manufacturer of flat glass. Schwoerer explains, ‘In the early ’70s the few American companies making opalescent glass were back-ordered for at least two years and weren’t taking on new customers.’ In the following years Ahlgren and Lundstrom both left to start up other glass-related ventures and Lani McGregor, now artistic director of the Bullseye Connection gallery, joined Schwoerer as partner in 1985.

Bullseye kept closely involved with the needs of the marketplace through direct connections with the art world. In the early 1980s Klaus Moje wanted to make kilnformed mosaic glass and needed colours that fused compatibly. He met Lundstrom at the Pilchuck Glass School and found they had a mutual interest in the development of what became Bullseye’s Tested Compatible sheet glasses. ‘Moje provided a huge further inspiration to continue on this path which really had no justifiable commercial rationale at that time,’ says Lani McGregor. This liaison had far-reaching repercussions, especially for Australians, because Moje moved to teach at the Canberra School of Art in 1982: ‘Bullseye made hand-rolled glass for architectural purposes. They saw the problems I had with compatible glass and a limited colour palette…[and] started to see a serious way of entering the studio glass movement with their product.’

By the 1990s Moje wanted to make vessel forms from his fused mosaic sheets. It required further collaboration to develop a glass working process to enable this to happen. He first tried with Bullseye glass at Pilchuck with glassblower Billy Morris in 1987 and again with Dante Marioni in Portland in 1993. Bullseye provided a compatible blowing glass for these sessions, where the sheets were wrapped around a gather of furnace glass, but ‘what eventually came out of them’ says McGregor, ‘was that Klaus discovered that a blowing glass is not necessary for blowing previously fused forms. What Dante was doing was a variation on the long-known Italian pick-up method. What evolved was the truly amazing Australian Roll-up that – although we do now make a blowing compatible glass – doesn’t need it’. Artists were to discover, however, that the provision of these two compatible glasses allows other processes to take place, where, for example, sections of blown and fused glass can be successfully joined using the encalmo technique.

Bullseye’s connection with Australia was established mainly through Moje’s interest in providing opportunities for graduates and colleagues to travel, study and exhibit elsewhere, that were continued later by his successor Stephen Procter, and Jane Bruce. In turn Bullseye became involved in supporting programs in Australia, the most notable being the Latitudes workshops and exhibitions of 1995 and 1997 organised at the Canberra School of Art by Kirstie Rea, where participants experimented with the many options now possible. Kirstie Rea and Scott Chaseling continued their own explorations of these new possibilities, and became well-known in the 1990s for their international ‘Roll-up’ workshops.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at top, Carved form, Echidna shape, bean wood / echidna quills, painted, Louie Pwerle, Ngkawenyerre camp, Utopia, Northern Territory, Australia, 1996; and at second top, Figure, dog, Devil Dog, wood, Billy Petyarre, Utopia Station, Northern Territory, Australia, 1991; at second bottom, Coolamon, Bush Tomato Dreaming, wood / acrylic paint, Billy Petyarre, Utopia Station, Northern Territory, 1990-1991

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at top, Carved form, Echidna shape, bean wood / echidna quills, painted, Louie Pwerle, Ngkawenyerre camp, Utopia, Northern Territory, Australia, 1996; and at second top, Figure, dog, Devil Dog, wood, Billy Petyarre, Utopia Station, Northern Territory, Australia, 1991

Louie Pwerle (Cowboy ‘Louie’ Pula Pwerle (Australian, c. 1940-2022)(Ngkawenyerre camp, Utopia, Northern Territory, Australia)

Carved form, echidna shape

1996

Bean wood/ echidna quills, painted

Height: 160 mm

Width: 170 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1996

Carved Echidna by Louie Pwerle

Carved animals and dishes, and painted seed necklaces, are made variously by artists including Queenie Kemarre, Louie Pwerle, Billy Petyarre, Wally Pwerle, Elizabeth Kngwarreye, Angelina Pwerle at the Ngkawenterre camp in the Utopia homelands. This particular camp is known for the carved animals made there.

Goannas, lizards, echidnas and kangaroos are sought after for food, as ‘bush tucker’, while the dogs are ‘devil dogs’. The devil dogs assist the ritual law enforcer, Kwertatye, in the beliefs of this group of Aboriginal people. Carved figures were made in earlier times, but it is not known what these were. The Ngkwarlerlaneme people at Utopia have revived the practice, following the introduction of acrylic painting in the 1980s; the dogs are painted in the manner of acrylic painting. Similalry the silk batiks made by this group often include figures or representations of animals and figures, real or mythological.

Designed and made by Louie Pwerle from a soft wood, locally called beanwood. The echidna is well-known as a form of bush tucker. Louie is part of a family who live at the Ngkawenterre camp in the Utopia homelands, and mostly carves and paints animals. He made three kangaroos in 1989 and none other until 1996, after Rodney Gooch brought back a ‘tree kangaroo’ (squirrel or possum) from Indonesia; following this Louie started to make kangaroos again. Only a few echidnas appear to be made (about 12 in the last 6 years), and only two with real quills seen by the Sydney agent in the last few years. This is (in 1996) the only camp where carved animals, figures and bowls are made, and paintings on canvas are also made at this camp. All the works in this particular collection are made by members of this family at this camp. All are consistent carvers, some like Queenie and Louie since about 1988.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

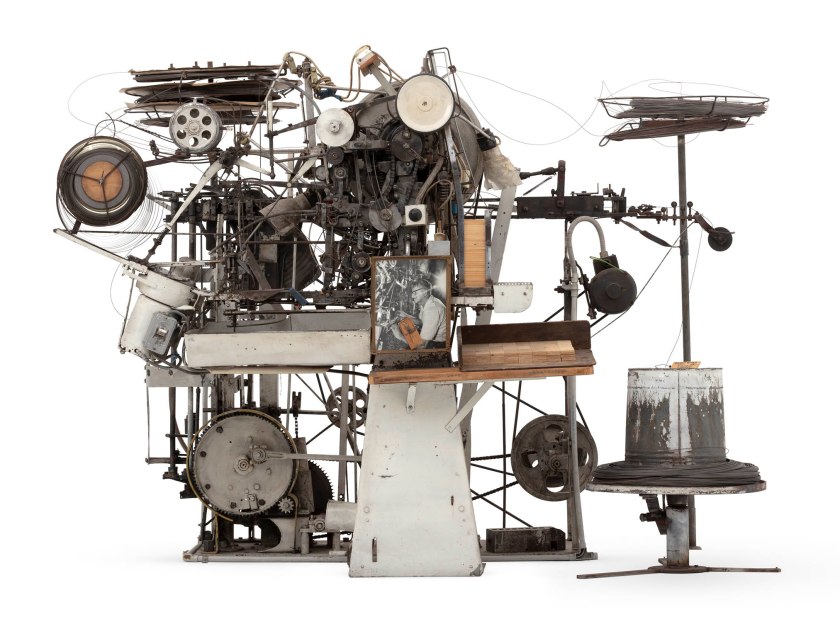

AW Standfield and Co (manufacturer, Mascot, New South Wales, Australia, active 1925-2000)

‘Supreme’ Mouse Trap Making Machine

1942-1943

Metal/wood

1950 mm H x 2470 mm W x 1500 mm D

Weight 830 kg

Powerhouse Collection

Acquired October 2001

‘Supreme’ Mouse Trap Making Machine

This mouse trap making machine is part of the Museum’s Standfield collection of trap-making machines and associated items which are an unusual, indeed curious, ensemble of purpose-built machines and products that defined an Australian industry for sixty years.

The collection exemplifies a ‘making do’ approach to manufacturing in that the machines were built from secondhand parts from a range of sources; it also exemplifies the notion of technological stasis in that the machines were always considered efficient and sophisticated artefacts for the making of rodent traps. Likewise, the organisation, traditional skills, and daily customs of the Standfield firm did not change from the Second World War to the end of the twentieth century, a period when rapid industrial change was the norm.

The nature of production at Standfields was based on a belief that a unique machine would provide a quality product whose market was based upon the natural cycle of rodent population size. According to the Standfields, production was never based upon the traditional economic factors of supply and demand, as these concepts did not seem applicable to a production facility of this nature, size, and scale. Productivity was rarely increased or decreased from the machine’s range, that is, 1,000 traps per hour. Product stockpiling was a normative value that was practised by the firm.

Less demonstrative, but deeply embedded in the Standfield approach to manufacturing, was a belief that a well-made and simple product defined an Australian approach to the making of things.

The mouse trap making machine is made from a variety of metal and electronic components, painted white for framework and left plain for working parts. The machine can be divided into two segments consisting of the mouse trap assembly line and the spring and hammer making mechanism.

The front section of the machine features the assembly line from right to left. This section contains an intricate series of levers, pulleys and gears which feed the wooden mouse trap platforms through the production line. On the right is the platform feeder, filled with wooden platforms. From here the bases are pressed in a stamper, leaving the imprint, ‘Supreme / MOUSE TRAP / MADE IN AUSTRALIA’ on the top. The next phase involves the the catch or baiter and the holding bar both being stapled on to the platform. Once through this process, there is an open section in the centre for a worker to manually attach the spring and hammer device to the mousetrap and then place the traps back in the conveyor channel. The traps then pass through a plane or sander to remove any points on the base, and the process is complete. The power switch for this portion of the machine is positioned just below the sander, with a speed switch also present in the machines centre. On each side of the production line segment are different coils of metal, for each of the components used in constructing the mouse traps. Each of the coils is labelled with different specifications, based on their thickness, with some spare coils placed underneath. A counter, in a red casing, can be seen in the centre of the machine, indicating the number of traps which have been processed. Above the counter are two lamps, plugged into a powerboard at the top of the machine, for providing additional light in the dark workshop.

The back section is designed with the specific purpose of constructing the spring and hammer mechanism for the traps. This section also works like a production line with two sets of metal coils, suspended on metal poles, on the right and left sides of the machine. The wires are fed through a set of gears, pulleys and levers, which bend, coil and shape the wire to create the spring and hammer. The finished product reaches the end of the production line and is released down a slide or ramp, into a white tray at the front of the main production line for the worker to retrieve. A power switch can be found on the right side of this section

At the front of the machine is a black and white image of Arnold Wesley Standfield woking on the machine, with the final mousetrap that the machine made stuck to the front. A number of finished and half finished mousetraps as well plain platforms can be found on a wooden shelf on the machines right.

Formal patent applications were taken by Arnold Wesley Standfield for the ‘Westan’ all metal rodent trap, and the Kyogle cow-tail clip. The patent documents are supplemented with schematic designs, which illustrate the operational requirements of the products. Interestingly, no formal machine design or patent was ever taken on Standfield’s principal item, namely, the mouse-trap machine. The Standfield archives hold the patent applications for the ‘Westan’ mouse trap and Kyogle cow-tail clip, as well as other documentary accounts of these items.

The machines, traps, and the cow-tail clip, were entirely the creations of Arnold Wesley Standfield (1901-1990), the founder of A.W. Standfield and Co., ‘Supreme’ Mouse and Rat Traps. His sons Dave and Ron Standfield assisted their father with the repair and maintenance of the machines, and the sons became the owners and managers of the firm upon the death of their father. Knowledge of the machines and its products was passed to the sons by their father, and in turn they passed on knowledge and skill to long-term employees of the firm.

A.W. Standfield made the machine from wheels, gears and pieces of metal taken from scrapped machines he found in scrap-iron yards around Sydney. Although Standfield had no formal training in machining or associated trades, his accomplishment does suggest that he had an innate ability to build production machines. In a single operation, a mouse trap can be assembled in 1.5 seconds. The standard production rate is “over 1,000 traps per hour” (‘Mouse-Trap Making Machine’, n.d. probably composed by A.W. Standfield, Standfield archives).

The machine was made over a two-year period (1942-1943) and the first traps ‘came off’ the machine on 7 January, 1944. The machine is as it was first made, although broken and worn parts have been replaced over the years.

The machine itself makes all parts, and, as mentioned above, assembles a trap in 1.5 seconds. In operational terms, four strands of staple wire are fed, straightened, cut off, folded and driven into the base of the trap. The machine grounds off protruding staple ends. It feeds, straightens, cuts off, and forms into a trigger, wire of 3″ (76.2mm) length of 17 gauge wire, which was supplied by BHP. The machine staples the trigger wire to the pine base.

The machine makes and assembles the bait holder. The machine selects the length of steel for the bait-holder, cuts it, punches and forms the steel into the bait holder and affixes the holder (under the staple) to the pine base. The machine feeds, straightens, and cuts off 18″ (457.2mm) of 17 gauge spring wire and forms this as the mouse-trap spring. In the process, the wire is turned and bent 23 times at varying degrees to make a spring. The mouse-trap machine pushes the piece of pine along a slot and brands the base. The machine turns the spring ends. The spring is fed through and stapled by hand to the base. This operation completes the assembly of a mouse trap.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Lockheed Aircraft Company (manufacturer, Burbank, California, United States of America)

Aircraft undercarriage from Lockheed Altair monoplane ‘Lady Southern Cross’, starboard side

Probably 1933

Metal/rubber

Height: 1420 mm

Width: 480 mm

Diameter/Length: 1000 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Acquired February 1994

Aircraft undercarriage from the Lady Southern Cross

The only surviving fragment of aircraft in which Sir Charles Kingsford Smith died, 8 November 1935

This wheel and oleo strut are part of the starboard undercarriage used by Sir Charles Kingsford Smith (Smithy) in his Lockheed Altair aircraft VH-USB ‘Lady Southern Cross’ for his attempt at a record breaking flight from England to Australia in 1935. On 8 November 1935 ‘Lady Southern Cross’ is estimated to have crashed into the Gulf of Martaban in the vicinity of Aye Island off the coast of Burma, now Myanmarm, at approximately 0216 local time. The undercarriage is the only major component to have been located and preserved after the loss of the aircraft with Smithy and his co-pilot/engineer, Tom Pethybridge, on board.

Sir Charles Kingsford Smith is Australia’s most renowned pioneer aviator. He established a number of records in a variety of aircraft, most notably the Fokker Trimotor, ‘Southern Cross’. His interest in competing in the MacRobertson Air Race of 1934 gave him the impetus to purchase the Lockheed Altair as an aircraft with the capability of achieving first place, but engineering problems and lack of time mean that he had to withdraw from the race. In testing the aircraft in Australia, he established a number of city to city speed records in the Altair. To ‘save face’ for withdrawing from the race he flew the Pacific instead in the west east direction establishing another record. Smithy and Tom Pethybridge, lost their lives endeavouring to break yet another record, the England-Australia speed record.

The single engined Lockheed monoplane aircraft of the late 1920s and 1930, encompassing the Sirius, Orion, Altair, Air Express, Explorer and Vega, were considered to be revolutionary in their time. According the their ‘biographer’, Richard Sanders Allen in ‘Revolution in the Sky’, those fabulous Lockheeds, the pilots who flew them, “…became the most copied, coveted, news making airplanes of their era”. They achieved a number of records in the hands of such famous aviators as Amelia Earhart, Charles Lindbergh, Wiley Post, Hubert Wilkins and Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, to name a few. As well as providing record breaking aircraft the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, as it became, used the basic designs and manufacturing techniques to produce small airliners such as the Orion, Air Express and Vega. After the completion of the last of this series of designs Lockheed went on to design and manufacture such significant airliners as the Lockheed 10 Electra and the Lockheed 14 Super Electra. During World War II, Lockheed designed the Constellation which became the backbone of many airlines restarting services post-world War II. Qantas based its fleet on the Constellation before converting to the gas turbine powered Boeing 707.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

John Lyon Gardiner (maker, Sydney Technical College, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia)

Model staircase

1891

Cedar (Toona australis)

Height: 2730 mm

Width: 1390 mm

Depth: 990 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Presented by Sydney Technical College, 11 November 1953

Model staircase

This model staircase is a significant example of the work of Sydney Technical College instructor, John Lyon Gardiner. It was built to demonstrate the principles of stair construction. Almost from its inception the Museum had a close relationship with the Technical College which was its immediate neighbour in Harris Street. At the time there was a new interest in education through observation or ‘learning by looking’. This was thought particularly important in the training of ‘practical men’ and museum’s were an essential part of this process. As the English philanthropist, Thomas Twining, wrote in Science made easy (1876) about the purpose behind his own Museum in Twickenham, outside London:

‘I became more and more impressed with the desirableness of propagating among the working population, sound practical knowledge calculated to secure for steady persevering industry, a well earned mead of Health and Comfort … [through] VISUAL EDUCATION.’

The staircase is made from cedar which is also significant as, at the time, the Museum was actively promoting commercial applications for colonial timbers.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

James Brewer (maker, Darlestone, United Kingdom)

Long case clock

1690

Wood/glass/brass/metal

Height: 2240 mm

Width: 495 mm

Depth: 300 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1963

John Dewe (maker, London, England)

Long case clock

1733-1764

Lapis-blue Japanned case, wood/metal

Height: 2240 mm

Width: 515 mm

Depth: 240 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1964

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at top, Man’s ceremonial headpiece (lamba), sheet gold alloy, Sumba, Indonesia, 1880-1950; and at second top, Textile length (mens waist cloth), handwoven cotton / shells / beads, maker unknown, East Sumba, Indonesia, 2000-2004

Installation view detail of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at top, Man’s ceremonial headpiece (lamba), sheet gold alloy, Sumba, Indonesia, 1880-1950; and at second top, Textile length (mens waist cloth), handwoven cotton / shells / beads, maker unknown, East Sumba, Indonesia, 2000-2004

Maker unknown (East Sumba, Indonesia)

Textile length (mens waist cloth)

2000-2004

Handwoven cotton/shells/beads

Width: 560 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 2010

Pictorial textile from East Sumba

This exceptionally long and narrow pictorial textile was woven on the island of Sumba in Indonesia. While the textile exemplifies the renowned skills of the Sumbanese women weavers, its design is highly innovative and a distinct departure from tradition. Innovation in textile design was not new to the Sumbanese weavers who certainly embodied strong traditions but who, under Dutch colonial rule, were encouraged to produce textiles specially designed to appeal to the Dutch market.

This long textile was probably produced for the tourist trade and reflects innovative approaches to design and production in several respects.

Supplementary warp patterning, known as pahikung on Sumba, has been used in the central decorative band for the full five metre length of the textile. In accomplishing such an extended length of pahikung, the weaver has produced a masterpiece of intricate and evenly tensioned weaving. This exacting technique was generally used for the short and highly decorative bands around a woman’s tube skirt or sarong whereas here it has been combined with the traditional five metre long men’s waist wraps called rohobanggi. However rohobanggi, which had a ritual function, were always woven with a simple design of stripes and had no additional ornament.

The most dominant motif in the textile, which is repeated in pahikung down the middle of the cloth, is a sailing boat with one person wearing a large hat at the tiller and three passengers. Boat motifs are not part of the traditional iconography of Sumbanese art; they are common in Sumatra however, where ‘ship cloths’ appear in several well-known forms. The ship imagery must have been brought to Sumba in some form, probably from Sumatra, for incorporation into the weavers’ design repertoire. Forming a wide border down each side of the cloth, are motifs traditional to Sumba which depict water creatures such as crocodiles, turtles and crayfish and have been worked in beads and small shells. Traditionally, shell decoration was also restricted to women’s tube skirts or sarongs.

Sumbanese textiles have changed significantly through interaction with the Dutch and other global markets, especially during the last decades during which tourism has grown exponentially in Indonesia. As exemplified in this remarkable example, textiles in Sumba today combine ancient ancestral symbols with contemporary images drawn from other sources. Their designers can pick and choose from a wealth of possibilities while still maintaining non-negotiable traditional design forms, weaving techniques and iconography.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing The Transparent Woman (1950-1953, below)

Installation view detail of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing a detail of The Transparent Woman (1950-1953, below)

The German Health Museum (Cologne, Germany)

Anatomical model, full size, ‘The Transparent Woman’

1950-1953

Used by Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 1954-2007

Perspex/aluminium/metal/wood/plastic

Height: 1740 mm

Width: 1060 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1958

The Transparent Woman

This the first transparent anatomical model of a woman ever to be exhibited in Australia.

In 1939 the director of the Museum, Arthur Penfold, embarked on an international study tour visiting many different museums and galleries overseas. He visited museums in both Chicago and New York and became captivated by their displays of transparent human models and their promotion of healthy living and sanitary practices. Due to lack of funding, the Transparent Woman was not acquired by the Museum until 1954. She was the first electronic scientific anatomical model to be displayed in Australia and was acquired to further the Museum’s mission to shape model citizens.

People have historically been curious about seeing what is inside objects, especially the human body. In the nineteenth century members of the public were able to witness dissections on cadavers; however the sights, and smells must have been overwhelming at times. The technology then became available to preserve human organs and make them semi-transparent by passing light through them. People were able to see what was inside the body without the blood and guts of dissections. Papier mache and wax models were used and, with advancements in plastics technology, clear and flexible plastic became available for model making.

These models were a German innovation, originating in the early 1930s at the Museum of Hygiene in Dresden. They served as a teaching aid for students of anatomy, and promoted a message of health and sanitation to the general public. The models were based on ‘perfect forms’, of young men and women, and symbolised the healthy body that people should strive to achieve. Germany was undergoing rapid industrialisation; thus prompted rapid urban growth accompanied by inadequate sanitation. The German Government promoted the use of these models as a way of educating and preserving a healthy working class. In the early 1950s the Health Museum in Cologne, West Germany, was established and began producing the transparent models and exporting them to America and other countries.

In the late 1930s some thought that the transparent models were symbols of Nazi ideal racial ideology, most who saw them were transfixed by the eugenic ideal of a healthy body. The Powerhouse Museum’s Transparent Woman arrived in 1954 to advocate a message of individual responsibility to maintain a healthy body.

It is hard to imagine being shocked or offended by this model, but the Transparent Woman must have been something of a spectacle in the 1950s. On importation it is recorded that one customs official was so offended by the nature of the exhibit that she almost never made it into the country. To cover some of the huge cost involved in obtaining the model, she was put on displayed in the State Theatre and the public were charged 2 shillings per adult and 9 pence per child to see her. The viewing sessions were segregated by gender and a trained nurse was on standby to assist if anyone was overcome by the experience. To add to the sensationalism she was marketed using images depicting a dark and shadowy ‘sex siren’ type of woman.

After several months at the State Theatre, the Transparent Woman was moved to the Museum where she continued efforts to promote health and hygiene. The accompanying souvenir booklet proclaimed, “The transparent woman will help us to understand the mysteries of our body, nature’s crowning masterpiece. The transparent woman tells us how our body is made and how it works [she] provides us with the means towards greater understanding of ourselves – so necessary to our wellbeing and healthy living, it is the responsibility of the individual to keep his body healthy so that he may live a useful and a successful life.”.

She later assisted in the Museum’s first attempts to discuss the subject of sex. During the 1970s and 1980s the museum utilised the Transparent Woman to provide human anatomy lessons for school groups. Children were allowed to ask questions and teachers were assured that the museum’s education officers would “endeavour to answer each question openly and as scientifically as possible if the subject of reproduction was raised”. The model was a significant public education tool and, as her accompanying booklet declares, “has helped lift the veil of mystery from womanhood”.

The Transparent Woman has a long history of service to Museum. Starting life as a controversial sensation, she then became the iconic symbol of the Museum’s hygienic crusade. In the past 50 years she has been used to demonstrate how the nervous system works, for sex education, and to demonstrate the areas of the body where contraceptive activities take place. The Powerhouse Museum has a collection of over 380,000 objects, only a small amount of which are on display at any one time, yet the Transparent Woman has spent little of her working life in storage.

References:

Correspondence. A. R. Penfold to F.R. Morrison, 27th Oct 1952, museum records.

The Transparent Woman [souvenir booklet]. Sydney, 1954.

Internal Correspondence. A.R. Penfolds overseas trip, 1939, museum records.

Internal Correspondence. Memorandum to the Secretary: Department of Technical Education, Sydney, From A. R. Penfold, Museum Director, 22nd November, 1954, museum records.

Terence Measham, Discovering the Powerhouse Museum, Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney, 1997, pp. 139-147.

Klaus Vogel. Manifesting Medicines, Bodies and Machines: The transparent man- some comments on the history of a symbol, Harwood Academic Publishers, Netherlands, 1999.

Graeme Davidson and Kimberley Webber. Yesterday’s Tomorrows: The Powerhouse Museum and its Precursors 1880-2005. Powerhouse Publishing, Sydney, 2005, pp. 68-81.

The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences Annual Report, 1954, museum records.

Written by Erika Dicker

Assistant Curator, October 2007

A life-size anatomical model of a woman with transparent plastic casing revealing her internal construction. The skeleton is cast aluminium painted white. The arterial and venous systems are represented by red and blue coloured plastic tubing. The nervous and lymphatic systems are represented by brown and green coloured plastic tubing.

The body organs and brain are made from pink, orange, brown and yellow plastics. The plastic organs consist of the brain, larynx, thyroid gland, lungs, heart, liver, gall bladder, spleen, pancreas, stomach, small intestine, caecum, transverse intestine, large intestine, rectum, kidneys, bladder, ovaries, womb and breasts. The organs and brain are fitted with small pilot lights that are controlled from the console to illuminate during different parts of a pre-recorded presentation.

The figure is standing on a turntable, is raised on a two tier platform, which contains rotating mechanisms and loud speakers. The wooden console contains an automatic operating tape recorder and relay switches to operate lighting of organs and rotation of figure.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Philippe Starck (designer) (French, b. 1949)

Daum Crystal (manufacturer, Nancy, France)

Table vase, ‘Quatre Etrangetes sous un mur’ (Four curiosities below a wall)

1988

Glass

Height: 490 mm

Width: 600 mm

Depth: 500 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1996

Vivienne Westwood (designer, London, England) (English, 1941-2022)

Shoes (pair), ‘Super Elevated Gillie’, ‘Anglomania’ collection, Autumn / Winter 1993-1994

1993

Leather/cork/silk

Height: 270 mm

Width: 68 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1997

Powerhouse today unveiled 1001 Remarkable Objects, a major new exhibition led by Leo Schofield AM.

‘Our vision for 1001 Remarkable Objects was a seemingly simple one: to create an exhibition celebrating the sheer scale, breadth and relevance of the Powerhouse Collection. But how to choose? We rejected the nomenclature of ‘treasures’ or ‘masterpieces’ and instead determined all choices must be in some way ‘remarkable’ – whether by virtue of rarity, visual appeal, social history or an ability to invoke wonder. The result is a cornucopia of eras, styles, form, function, size and colour, to stoke memories that so many have of this iconic institution and signal the beginning of a new phase in its marvellous existence’, said Curatorium Chair Leo Schofield AM.

Leo Schofield AM has a long association with Powerhouse, as a former member of the Board of Trustees and a significant donor. He has worked in collaboration with advisors Ronan Sulich, Mark Sutcliffe and Powerhouse curator Eva Czernis-Ryl to select 1001 objects from the more than half a million objects within the collection. This selection includes objects that have never been exhibited before alongside much loved collection icons.

The Powerhouse Collection will be presented across the applied arts and applied sciences including the decorative arts, jewellery, costume, textiles, furniture, clocks, musical instruments, industrial design and social history.

Exhibition designers Pip Runciman, Julie Lynch and Ross Wallace were invited to respond to underlying themes of nature, power, movement and joy. They have created an exhibition that features more than 25 rooms, presenting an unexpected juxtaposition of objects and leads visitors on a journey across time and memory.

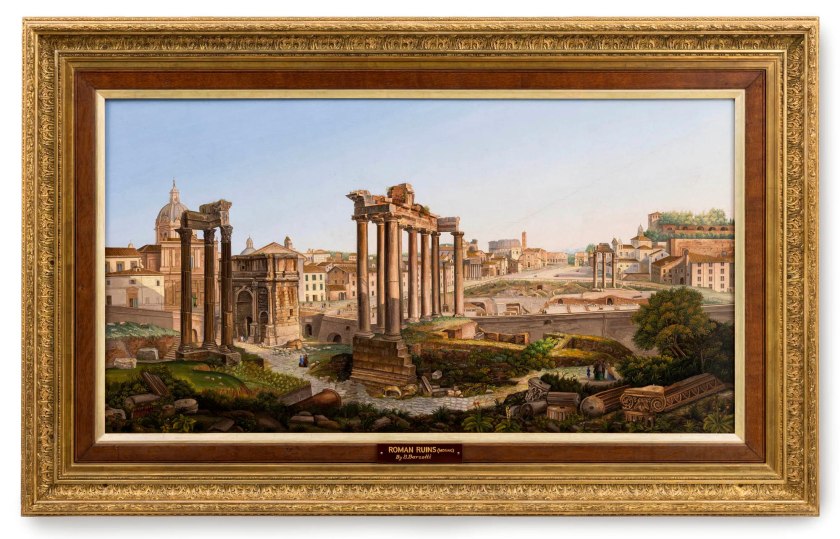

Extraordinary objects include a rare Meissen porcelain satirical portrait bust of the court jester known as Baron Schmiedel, made in 1739; the only surviving fragment of the Lockheed Altair aircraft Lady Southern Cross flown by pioneer aviator Sir Charles Kingsford Smith for his final flight in 1935; an Edo period samurai warrior’s suit of armour; and a Detroit Electric car manufactured in 1917.

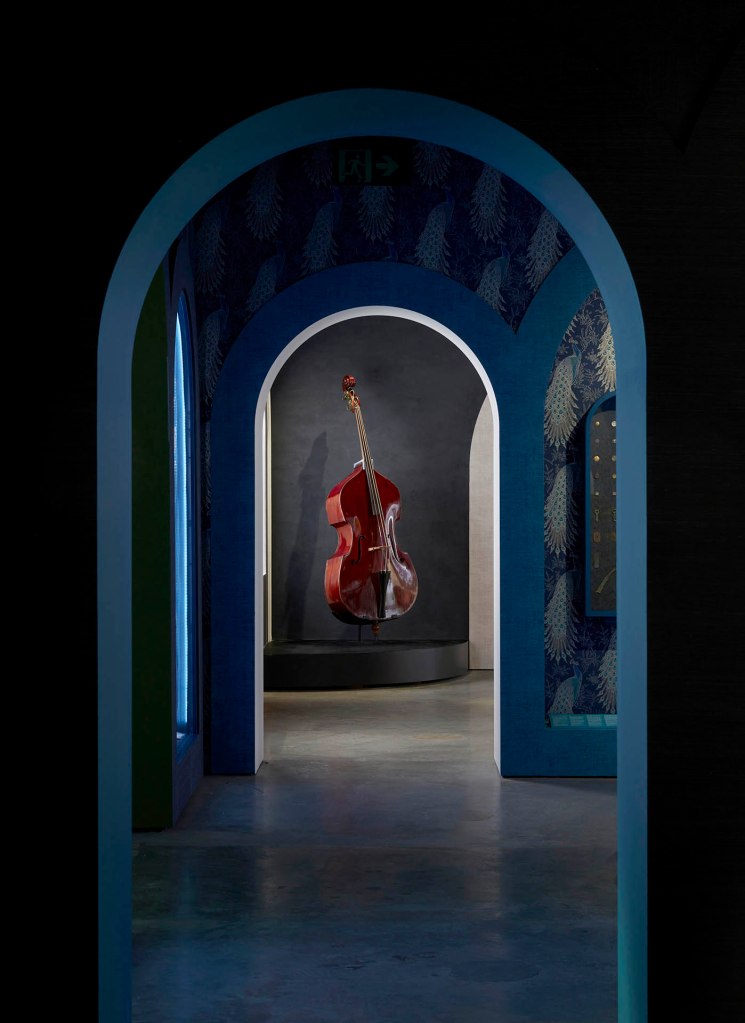

Musical instruments include a double bass made in 1856 by John Devereux, one of the oldest surviving bowed string instruments made in Australia by a professional instrument maker; an acoustic guitar decorated with hand painted designs by Harold ‘The Kangaroo’ Thornton; and an upright bookcase grand piano, made in 1809.

Fashion highlights include a 1700s court dress; an evening dress by Gabrielle ‘Coco’ Chanel for her Spring collection of 1939; a pair of Super Elevated Gillie platform shoes by British designer Vivienne Westwood from Anglomania, her Autumn/Winter collection 1993-1994; and Romance Was Born’s 2009 ‘Iced VoVo’ dress.

Costumes include the ‘Showgirl’ costume worn by Kylie Minogue for the Closing Ceremony of the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games; the ‘Pink Diamonds’ dress worn by Nicole Kidman in the Baz Luhrmann film, Moulin Rouge and the ‘Fruity Mambo’ costumes designed by Catherine Martin for Strictly Ballroom the Musical.

More than 100 rare and remarkable pieces of jewellery will highlight a recent major donation by Anne Schofield AM. This includes Egyptian revival designs from the 1800s and mourning jewellery crafted from human hair, which will be on display at Powerhouse for the first time.

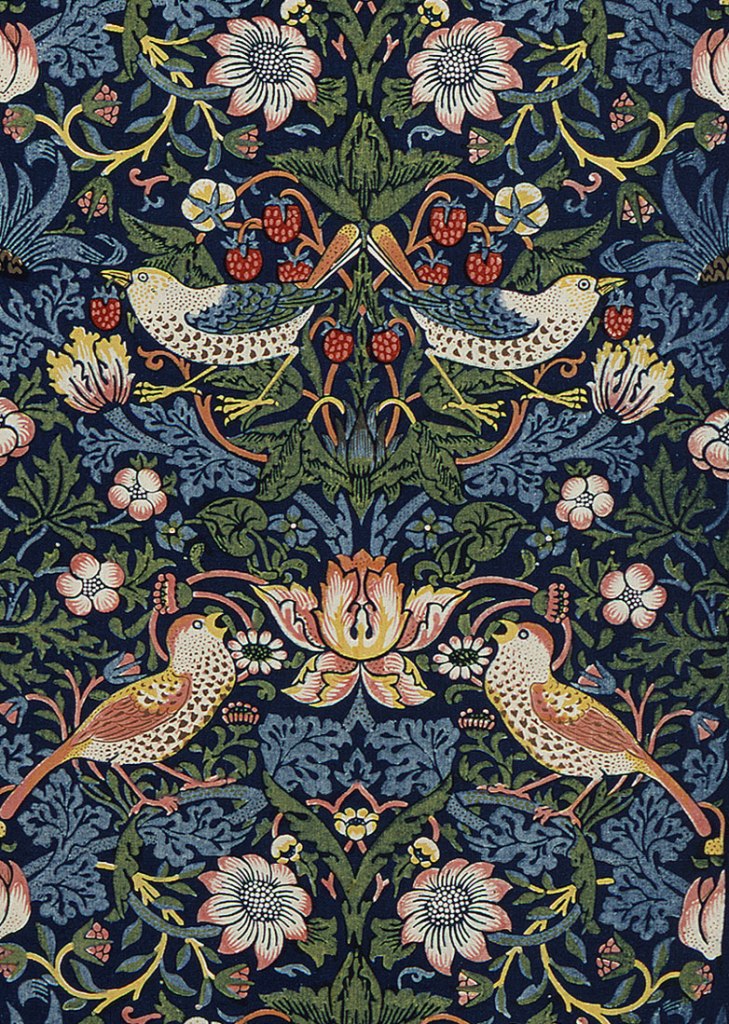

French and Venetian glass from the 1800-1900s will be presented, as will an English stained-glass window, ‘The Delphic Sibyl’, based on an 1873 painting by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones made by Morris & Co about 1900, alongside key examples of Australian and international studio glass ranging from Dale Chihuly to Canberra-based artist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello and Sydney-based artist Brian Hirst.

‘Leo Schofield and his collaborators, through this exhibition, shed new light and new perspectives on the Powerhouse Collection. In 1001 Remarkable Objects we continue to extend our commitment to sharing with our communities the Powerhouse Collection and the many insights and connections it makes to both our past and our future’, said Powerhouse Chief Executive Lisa Havilah.

Powerhouse will present two special Powerhouse Late programs presented in collaboration with Liquid Architecture. The first program on 5 October is an exploration of the unusual and remarkable sonics in response to the exhibition with creative practitioners who evoke a range of moods through their work. On 23 November, a range of artists will take inspiration from the designers who have created unique worlds for these objects in conjunction with a celebration to launch companion publication 1001.

Press release from the Powerhouse

J Hubert Newman (photographer, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) (Australian, c. 1835-1916)

Untitled [young boy in sailor suit]

Nd

Carte de visite

Paper/card

Height: 165 mm

Width: 107 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Acquired September 1984

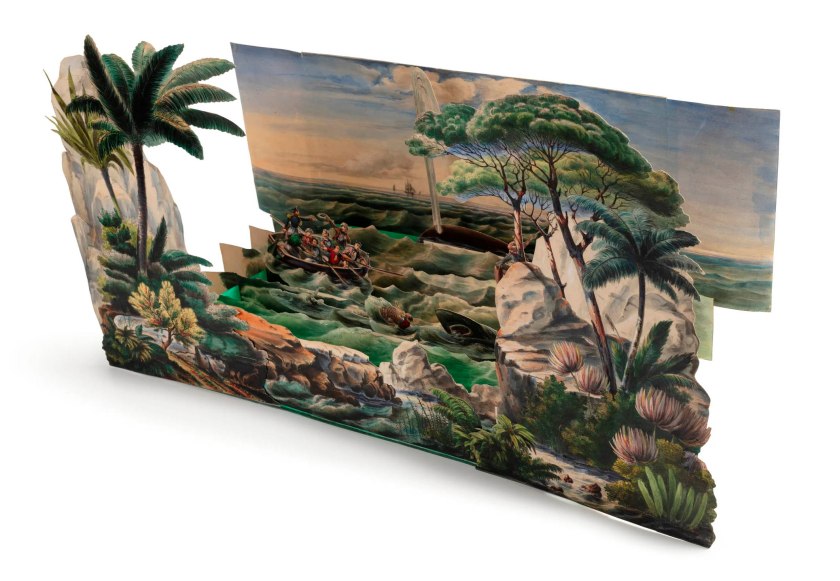

Charles Letaille (designer)

J Pintard (publisher, Rue Saint-Jacques, Paris, France)

Toy theatre, ‘La Pleine Mer, Scenes Maritimes en Action’

1836

Paper/cardboard/textile/metal/timber

Height: 320 mm

Width: 704 mm

Depth: 85 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased with funds donated by the Patrons of the Powerhouse, 1985

Children’s toy theatre, ‘La Pleine Mer’ (The Open Sea) by Charles Lataille

This extremely rare, hand-coloured, French children’s toy theatre ‘La Pleine Mer, Scenes Maritimes en Action’ (‘The Open Sea, Maritime Scenes in Action’) dates from 1836. The theatre comprises an ocean backdrop, a middle ground of waves and foreground of a South Pacific island reef. Numerous cardboard pieces of French ships, long boats, a drowning sailor and a shark attack can be slid in and out of the scene. By means of a booklet of seven short melodramatic plays (in French), to be read aloud by an adult or teacher, the drama and excitement of maritime adventures in the exotic South Pacific can be performed. The plays cover accounts of Australian aborigines fishing and building canoes, visits by French wayfarers to the Solomon Islands and Tahiti, and Maoris in New Zealand.

Many children’s theatres were made in the early 19th century with their popularity peaking between 1830 and 1860 when adult theatre was enjoying an unprecedented success with melodramas, masques and pantomimes. English toy theatres were the most complex often with a proscenium, stage, trap-doors, machinery for working curtains and trick effects, supports for scenery and a multitude of characters. However, Continental publishers produced simplified versions, although what they lacked in technical complexity was made up in settings and characters. French theatres, such as this one produced by J. Pintard in Paris, were noted for their beautiful hand-colouring.

Toys of the mid to late 19th century were designed to be educational rather than for play. The toy theatre, ‘La Pleine Mer’, would have instructed children in aspects of navigation, maritime life, exploration, geography and the people of the Pacific. The theatre features an unusual and appealing use of maritime pictorial material which is drawn heavily from books, paintings and journals of discovery of the day. It illustrates a popular representation of Australia and the South Pacific at the time. The theatre is one of the earliest graphic representations of Australia and the South Seas in the Museum’s collection. Furthermore, whereas the books, journals and paintings of this period survive in state, national and international libraries and art galleries virtually no toys depicting content related to Australia and the South Pacific in the 1830s are extant worldwide.

Margaret Simpson

Curator, Transport & Toys

August 2011

Mitchell, Louise, ‘La Pleine Mer Sailing over a cardboard sea’, in The Australian Antique Collector, 36th edition, 1988. pp. 37-41.

Publication of La Pleine Mer noted in Bibliographie de la France, 10 December 1836, p. 597, entry No. 6239.

Toy theatre comprising 27 printed and hand-coloured lithographic cardboard pieces, in a South Pacific setting. When assembled the theatre comprises a painted backdrop with two ships under sail flying French colours, a longboat pulling away, more ships in the background and a blue sky with clouds. Between this and the proscenium are five ranks of waves (two of which have wooden runners to support the moving pieces).

The foreground features lush tropical vegetation and a reef battered by breakers. It is in three parts with a base showing the shore and large pieces which are installed at the left and right composed of trees and rocks. There are seven separate lithograph boats, one for each of the plays, with a further six separate pieces to be added in where instructed in the script. The scenes are either fixed into slots in the foreground or locked into a balance placed on wooden runners obscured by the middle waves.

The script comprises a 32-page booklet designed to be read aloud by an adult or older child while the different scenes are activated. The plays depict customs of the Solomon Islands, Natives of New Guinea and Tahiti, whaling activity in the South Pacific and landing in New Zealand.

According to the ‘Bibliographie de la France’, this toy theatre was produced by J. Pintard on 10 December 1836. Pintard’s other toy theatres had titles including ‘Le Theatre Enfantin’, ‘Le Spectacle Asiatique’, ‘Ou Danse et Voltige sur La Corde’ and ‘La Voiere’.

In keeping with most toymakers of the period, Pintard produced a variety of toys and related material aimed at educating children in art, geography, scripture, history and natural history. Advertising his stock at the conclusion of the ‘La Pleine Mer’ script, he claimed “L’enseignement de la moral la plus pure forme la base de tous ces petits ouvrages instructifs” (“The moral teaching in its purest form is the basis of all these little educational works”).

This toy theatre, ‘La Pleine Mer’, includes seven plays written by Charles Letaille, who also produced the lithography. Letaille collaborated with his publisher to produce other children’s material during the 1830s and 1840s. The first play is entitled ‘The Sea, The Birth of Navigation’ and describes the simple craft of the natives of New Holland (Australia) and concludes with an account of the carved and outrigger canoes of New Guinea and Tahiti.

In the more dramatic second play, ‘The Whale’, native canoes are replaced with a spouting whale and a long boat from the whaling ship ‘Albatross’. The narrative begins in a bay of the Chilean coast and concludes with a whale-hunting drama. The play instructs children about the uses of whale products, (whale rib bones for umbrellas and whale fat boiled on board in large vats for oil) and includes a gruesome description of the sailors climbing over the carcass of the whale while tied to the side of the ship to remove the ribs, skin and fat.

The third and fourth plays, entitled ‘Man Overboard’ and ‘The Rescue’, describe an unlucky sailor falling overboard from the ship and being thrown a woven cane life preserver. In the meantime the ship is brought into the wind and the long boat launched for the sailor’s rescue.

The next play ‘The Shark’ begins with the deceptively calm description: “We are aboard the American three-master ‘Oceanic’ the sea breeze was barely enough to cause the waves to break on the nearby beach”. The pace picks up quickly with nail biting anticipation as it is revealed the ship’s master is repeatedly diving from the ship and hauling himself up on a rope to cool off from the heat while a short distance away a shark’s fin creates a “frothing shimmering wake”. Climbing into a small boat, the sailors go to his rescue. Gripped with fear they ‘could all foresee the struggle that was about to take place between themselves and the shark; a terrible struggle with a man as the contest’.

In the final play, ‘Putting in at New Zealand’, native figures are slotted into the foreground and a longboat is set into the waves. The play relates the meeting between French sailors and friendly Maoris. After an exchange of branches, the natives return with the sailors in their canoes and a priestess is invited on board ship. Attempts to rub noses with the ship’s steward end in chaos when he makes a sudden movement dislodging his wig and frightening the priestess into believing that he is a sorcerer.

According to Louise Mitchell in her article ‘La Pleine Mer Sailing over a cardboard sea’ many of the original details in the lithographs seen in this toy theatre can be traced to paintings, books and journals of the period. For example, the lithograph depicting New Holland natives tumbling from their capsized canoe while spearing fish, can be traced to an illustration by the Scottish engraver and miniaturist, John Heaviside Clark (c. 1777-1863). Clark had never seen Australian aborigines but adhered to the popular European imagery of them as being noble and savage sportsmen. The illustration appeared in a book published in London in 1813 with the title ‘Field sports & of the Native Inhabitants of New South Wales’, reprinted a year later as a supplement to ‘Foreign Field Sports, Fisheries, Sporting Anecdotes, etc’.

Several of the script’s plays can be traced to a journal entitled ‘La France Maritime’. The shark attack lithograph was derived from an American romantic horror-painting of 1778 by John Singleton Copley (1738-1815) ‘Watson and the Shark’. In the toy theatre play the man overboard facing a shark’s jaws of death is pulled to safety. Ironically, the victim in the play ends up being the 16-foot shark which is split open by the ship’s cook. In a scene which initially evokes terror the mood is transformed into humour when the sailors discover that a man’s otter-skin hat belonging to the ship’s doctor is inside the shark’s stomach. (Clothes and belongings hung over the side of ships were regularly eaten by sharks).

Other illustrations can be traced to ‘Le Voyage Pittoresque Autour du Monde’ also published in 1836 by the French explorer of the South Pacific renowned for his seamanship, Jules Dumont d’Urville (1790-1842). A canoe from the Solomon Islands and a Tahitian sailing boat are directly derived from d’Urville’s book.

By the 1830s Europeans were familiar with many popular accounts of seamen’s journals of scientific and exploratory maritime expeditions. Suitable pictorial material was also available from the atlases of the Pacific voyages of Cook, La Perouse, d’Urville and others, and were reproduced extensively in all kinds of publications.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Charles Letaille (designer)

J Pintard (publisher, Rue Saint-Jacques, Paris, France)

Toy theatre, ‘La Pleine Mer, Scenes Maritimes en Action’

1836

Paper/cardboard/textile/metal/timber

Height: 320 mm

Width: 704 mm

Depth: 85 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased with funds donated by the Patrons of the Powerhouse, 1985

Charles Letaille (designer)

J Pintard (publisher, Rue Saint-Jacques, Paris, France)

Toy theatre, ‘La Pleine Mer, Scenes Maritimes en Action’ (detail)

1836

Paper/cardboard/textile/metal/timber

Height: 320 mm

Width: 704 mm

Depth: 85 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased with funds donated by the Patrons of the Powerhouse, 1985

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at centre an architectural model of the Macquarie Lighthouse made by the Department of Navigation, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, c. 1880

Installation view detail of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing at centre an architectural model of the Macquarie Lighthouse made by the Department of Navigation, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, c. 1880

Architectural model, Macquarie Lighthouse, c. 1880

This lighthouse model is a record of a significant Sydney building and landmark. It shows the design of the second lighthouse built on the sight at Dunbar Head, Vaucluse, lit in 1883, and designed by colonial architect James Barnet. The original lighthouse, designed by convict architect Francis Greenway and lit in 1818 had deteriorated by 1823 due to the soft sandstone used in construction.

Scottish immigrant James Barnet arrived in Sydney in 1854. A trained builder and architect, he became Clerk of Works at the University of Sydney soon after his arrival. in 1860 he joined the Colonial Architect’s Office, and within two years was its Head. Barnet was strongly influenced by the Italian Renaissance, and had no sympathy for new American styles of architecture which were becoming fashionable in Sydney at the end of the century. He was equally critical of domestic architecture cluttered with ornamentation. As colonial architect for twenty-five years he has had a lasting influence the architecture of Sydney. As well as the genesis of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, the 1879 Sydney International Exhibition Garden Palace building, Barnet’s buildings include the 1857 new wing of the Australian Museum, the Sydney General Post Office at Martin Place, Customs House, Medical School Anderson Stuart building at the University of Sydney, Callan Park Lunatic Asylum, East Sydney Technical College, Darlinghurst Court House, Victoria Lodge at the Botanical Gardens, and Mortuary Station, Central Railway.

The Macquarie Lighthouse is Australia’s longest serving lighthouse, and its current state is still well represented by this over-a-century year old model.

Damian McDonald

Curator

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Department of Navigation, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia

Architectural model, Macquarie Lighthouse

c. 1880

Wood / plastic

Height: 1885 mm

Width: 975 mm

Depth: 420 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Gift of Port Authority of New South Wales, 2015

Installation views of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing 1880s Murano glass from Venice, Italy made by the Venice & Murano Glass and Mosaic Co. (except from the very top piece in the first image, which is a vase, ‘Ronces’ (Thorns), model 946, glass, designed by René Lalique, 1921, made by René Lalique et Cie, Wingen-sur-Moder, France, c. 1950)

W & M Stodart (maker, London, England)

Upright grand piano

1809

Timber, metal/ivory/fabric

Height: 2480 mm

Width: 1100 mm

Depth: 560 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Bequest of Mr William F Bradshaw, 2010

Upright Grand Piano by W & M Stodart

This upright grand bookcase piano is the first of its type to enter the Powerhouse Museum’s collection and the earliest upright piano to be found in it. Dating from 1809 it is made by one of London’s leading piano manufacturers, Matthew and William Stodart, and one of the few examples of this type of piano to be found in Australia. Apart from its rarity it is significant for its construction and design showing the transition from the standard horizontal grand piano to the cabinet piano, which then developed further into the upright piano known today.

This style of upright grand is also unique as it was purposely designed to incorporate a bookcase and therefore had the dual function of musical instrument and drawing room furniture. The style was first patented by William Stodart, one of the makers of this piano, in 1795. Rosamond Harding recounts that Joseph Haydn visited the Stodart shop and “expressed himself delighted with the new possibilities it foreshadowed in case-making and with the quality of tone.” (Harding, p. 63).

Unlike later upright pianos the design is similar to a horizontal grand which has been inverted to the vertical from the keyboard. This accounts for the great height of these instruments, having approximately the same string length as horizontal grand pianos of the time. The bookcase piano was an ornate instrument and expensive to buy as well as produce. This together with their unwieldy height and lack of portability as well as tuning difficulties contributed to bookcase grands only being produced up until about 1825. From this time the upright idea evolved further into the cabinet piano where the string and soundboard section of the piano was dropped to floor level thus reducing the height. This created other problems related to the position the hammers needed to be in to strike the strings to produce an optimum tone. This lead to further developments in piano action design to overcome the problem.

However, the trend to make pianos as ornate pieces of domestic furniture continued well into the 19th century when cabinet pianos would continue to be decorated with ornate fabric fronts or large mirrors, suitable for large domestic rooms.

Michael Lea

Curator, music & musical instruments

March 2010

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Installation view of the exhibition 1,001 Remarkable Objects at Powerhouse Ultimo, Sydney showing John Devereux’s Double bass (1856, below)

John Devereux (Australian born England, (c. 1815-1883)(maker, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia)

Double bass

1856

Red brown varnish, European Spruce/European Maple/Australian Cedar/brass/paper

Height: 1990 mm

Width: 655 mm

Depth: 385 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased with the assistance of the Australian Government through the National Cultural Heritage Account and supporters of the Powerhouse Museum Foundation and the Pinchgut Opera, 2007

Double Bass made by John Devereux

John Devereux is one of the earliest violin makers known to have been working in Australia and is seen as Australia’s first professional bowed string instrument maker. He had a significant reputation and output from the 1860s to 1880s and was a contemporary of Australia’s other great maker of this period William Dow, also of Melbourne. Born in England in 1810, Devereux arrived in Australia in 1854 from London where he had been working in the workshop of violin maker Bernhard Simon Fendt (1800-1852). He settled in Melbourne and operated a violin making business there until his death in 1883. Apart from double basses he is known to have made violins, violas and cellos. He was apparently an accomplished double bass player and performed regularly at Government House in Melbourne. …

This double bass is possibly Devereux’s earliest instrument made in Australia that still survives. The instrument is made as a 3 string rather than 4 string bass which denotes an early period in bass making generally. Although the label is not original the bass has all the same characteristics of Devereux’s other instruments including two features that typify his work in Australia – his use in his double basses of Australian cedar especially for the back and an internal tension bar running the length of the body of the instrument from top to bottom. Independent assessments of the instrument also confirm this as a Devereux instrument. Most Devereux instruments remaining in original condition contain the tension bar which he devised in Australia to strengthen the instrument and prevent twisting of it in the Australian climate. This rigidity was also a way of keeping his instruments in tune in the local climate. There are only 4 other Australian made Devereux basses known to exist which date from a later period to this one.

In addition to the double bass the Powerhouse Museum also contains 2 violins by Devereux dating from 1869 and 1871 respectively, a viola by Devereux dated 1869, the 1866 gold medallion inter-colonial exhibition award, referred to above, and a separate tension bar and labels.

The exact number of instruments John Devereux made is unknown. Double basses made by Devereux both when he worked in London and in Australia survive, however, only five Australian made basses are currently known. Devereux also made violins, violas and cellos in Australia and examples of his work in general exist. He exhibited in a number of inter-colonial exhibitions and the catalogues of these mention the types of instruments he made. These catalogues also state that he used both European and Australian native timbers for his instruments.

Michael Lea,

Curator, music and musical instruments

May 2007

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Lorenzo (maker, Japan)

Guitar

c. 1975

Painted and used by Harold ‘The Kangaroo’ Thornton, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, 1980-2000

Handpainted, wood/nylon/plastic/metal/paper

Height: 1150 mm

Width: 375 mm

Depth: 97 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Gift of Philip Thornton, 2018

Hand painted Guitar by Harold ‘The Kangaroo’ Thornton

The guitar is part of a collection of extraordinary outfits and objects belonging to artist Harold ‘The Kangaroo’ Thornton (1915-2004), the creator of one of Australia’s rare historically themed art works, ‘Dr Brown and Green Old Time Waltz’. Hand painted by Harold, the guitar beautifully represents Harold’s personality and passion for art which shines through all of his works. In common with the other painted pieces in the collection, the artwork on the guitar is characterised by a sense of exuberant boldness and carefree abandon. The use of kaleidoscopic colours, uninhibited patterns both geometric and organic, mirrors Harold’s sense of playfulness and joy for life.

Largely self taught, Harold began painting at 8 years of age following the traditional art conventions of the times. It wasn’t until the 1980s however that Harold began painting in the style that perfectly matched his personality and philosophy of life. Stylistically, his work has been described as ‘psychedelic, naive or magic realistic’. Harold was never interested in making money or being aligned to a specific genre. His single-minded focus was to paint whatever took his fancy in his own inimitable way.

Several well-known Australian artists including Ken Done, Martin Sharp and body artist, Tim Gratton acknowledge Harold’s influence on their work. Largely denied recognition as a serious artist in life, over time there has been a growing appreciation of Harold’s artistic gift.

Glynis Jones and Wendy Circosta, 2017

Curator and Curatorial Volunteer

This guitar was hand painted by artist, Harold ‘The Kangaroo’ Thornton in Sydney possibly between 1980 and 1995.

Prominent Australian, Dr Bob Brown has described Harold as a ‘very unusual character. He had a little goatee, a wisp of beard coming out of his chin and he had a naked woman enamelled on to one of his teeth.’ Born in Enfield, an inner west suburb of Sydney, in 1915, Harold Leslie Thornton began his art career at the age of 8 when he used to write signs for the local butcher and grocer. Finding school a waste of time, he left at age 14 to work as a sign writer, learning by watching how others worked. In later years he spent some time at the Julian Ashton Art School and Desiderius Orban School of Art (1944-46), though he remained largely self-taught. In 1937, Harold departed Sydney with a friend on a motorbike and ended up settling in Griffith, New South Wales until 1941. Painting and wrestling were sources of income at this time. During the remainder of World War II, he lived in Sydney and worked as a sign painter at several places in the war industry. It wasn’t until after World War II that Harold began painting in earnest.

Harold returned to Griffith in 1947 and ran a sign writing business. In 1950 he began touring the Australian countryside setting up his own mini exhibitions in places such as Condobolin, Leeton, Wagga Wagga, Wollongong and Griffith for the next 10 years. He returned to Sydney in 1963.

He has said in both print and recorded interviews that he didn’t fit the mould of what the established art world considered an artist. From head to toe, he dressed flamboyantly in clothes which he’d fashioned and painted and he revelled in fun, whimsy and theatricality that had the art world questioning, ‘was he an artist or a showman’. Self-styled ‘ The Greatest Genius That Ever Lived’, Harold believed very much tongue in cheek that ‘You are what the public thinks you are so I’m the greatest genius that ever lived!’

Not represented by any local dealers and disenchanted with the power of art critics to make or break an artist, Harold left Australia to live in Papua New Guinea from 1968-1970 before making his way to Amsterdam where he spent many years creating art, writing songs and modelling for art classes. In Amsterdam, Harold received the recognition that the Sydney academic art world denied him. Known for his painted murals on shop windows, he was a well-loved and recognised figure in Amsterdam. His most famous mural was painted in 1975 on ‘The Bulldog’, one of the first establishments where marijuana from around the world could be sampled. It is now a landmark site protected by the Netherlands National Trust.

Harolds’s earlier works followed the more conventional style of realistic portraiture and landscapes. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Harold developed his own ‘magic realistic’ style. Nonconformist and reminiscent of psychedelia describes not only his art but Harold himself. A larger than life figure, he dedicated his life to his art, surrounding himself with objects that had received the ‘genius’ treatment, including clothing, accessories, his van, and a guitar and suitcase which are both included in the Museum’s collection.

Professionally, Harold had three portraits selected as finalists in the prestigious Archibald Prize which is held annually at the Art Gallery of NSW: comic Roy Rene (1948), Al Grassby (1982) Minister for Immigration in the Whitlam Government and Dr Bob Brown (1983), founder and leader of the Greens political party. Dr Brown was the subject of a very important Australian historical work, ‘Dr Brown and Green Old Time Waltz’ which is held in the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. It documents the story of one of Australia’s most controversial environmental issues – the Gordon-below-Franklin Project. He also held several exhibitions in Sydney, Griffith and Amsterdam and has influenced well known Australian artists, Martin Sharp, Ken Done and Tim Gratton.

Harold died on 7 April 2004, leaving an archive of over 200 paintings. His greatest wish was for all of his paintings to be in the one place on permanent exhibition.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website

Edward William Godwin (designer) (English, 1833-1886)

William Watt (maker, England, 1834-1885)

Sideboard

1867-1880

Oak/metal

Height: 1810 mm

Width: 2550 mm

Depth: 520 mm

Powerhouse Collection

Purchased 1991

Sideboard designed by Edward William Godwin

Edward William Godwin (1833-1886) was one of the most important designers of the English design reform movement in the second half of the 19th century. He was an active and influential member of the Aesthetic Movement and the first 19th century English furniture designer to turn to Japanese art for inspiration. His emphasis on the need to reconcile function and design, utility and beauty did much to redirect Victorian design and is now believed to have influenced the direction of 20th century design. The Anglo-Japanese sideboard is one of the earliest pieces of furniture by Godwin and expresses his enthusiasm for Japanese design as well as the importance he attached to function, lightness and simplicity. The sideboard remained his most radical Japanese-inspired design and is his best known piece of furniture.

Text from the Powerhouse Collection website