Exhibition dates: 16th June, 2023 – 21st April, 2024

Curator: John Stauffer, the Sumner R. and Marshall S. Kates Professor of English and of African and African American Studies, Harvard University

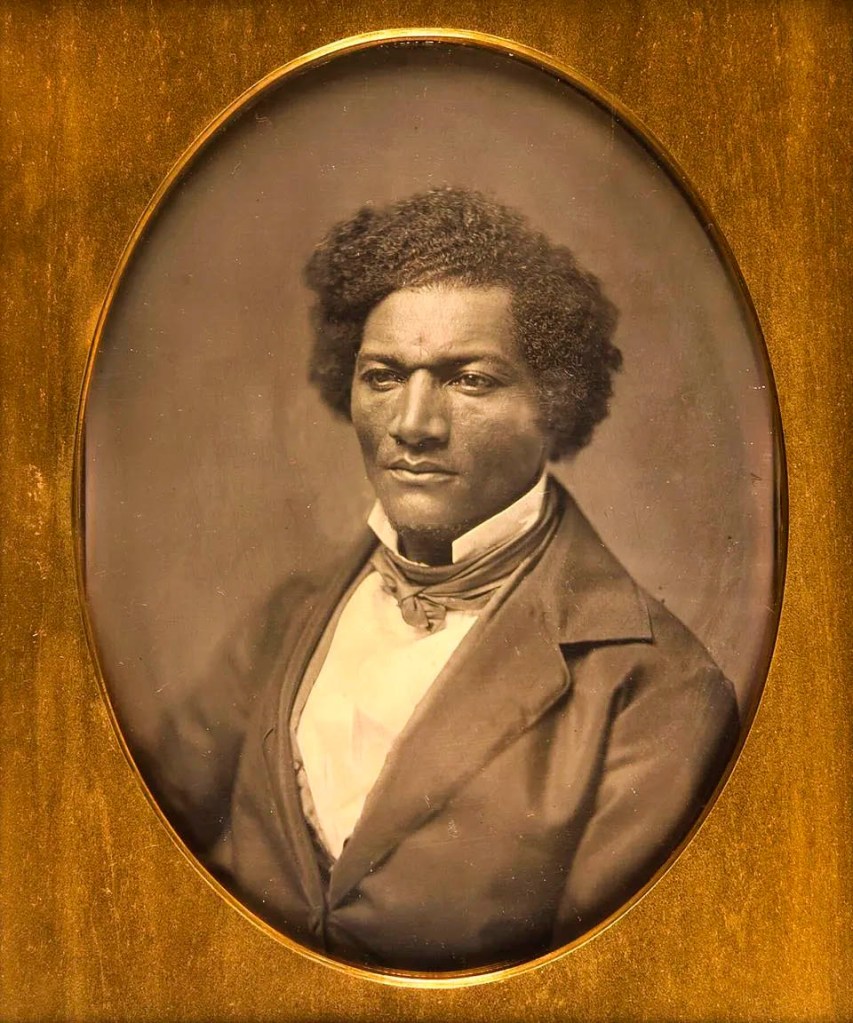

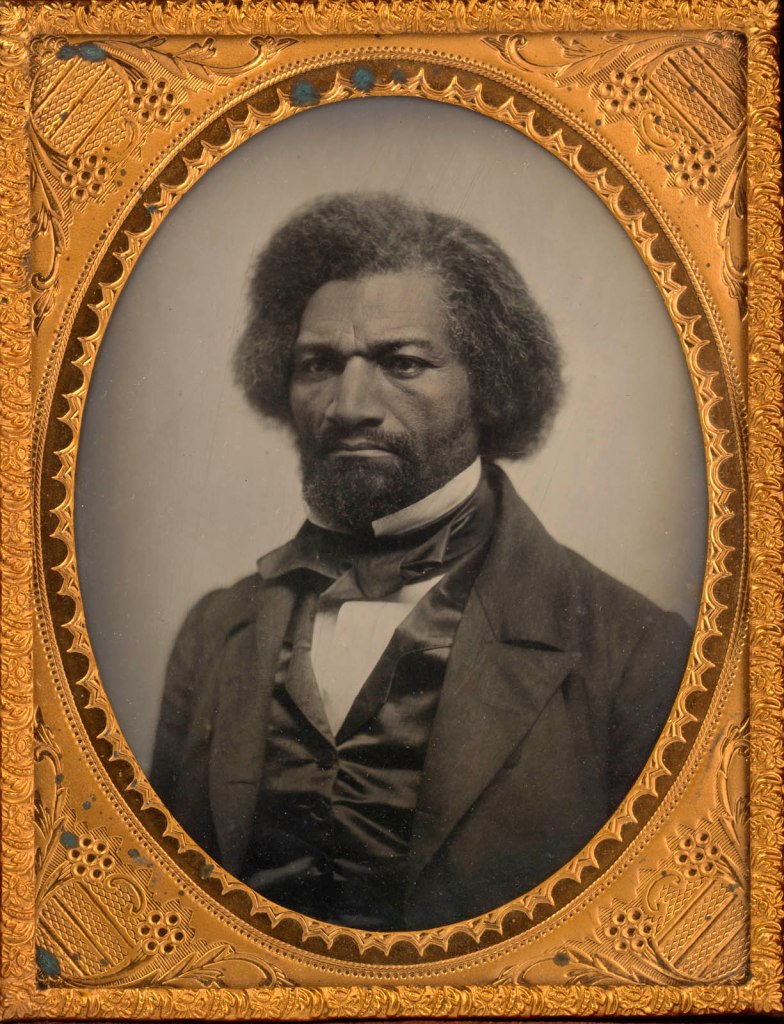

Unidentified photographer

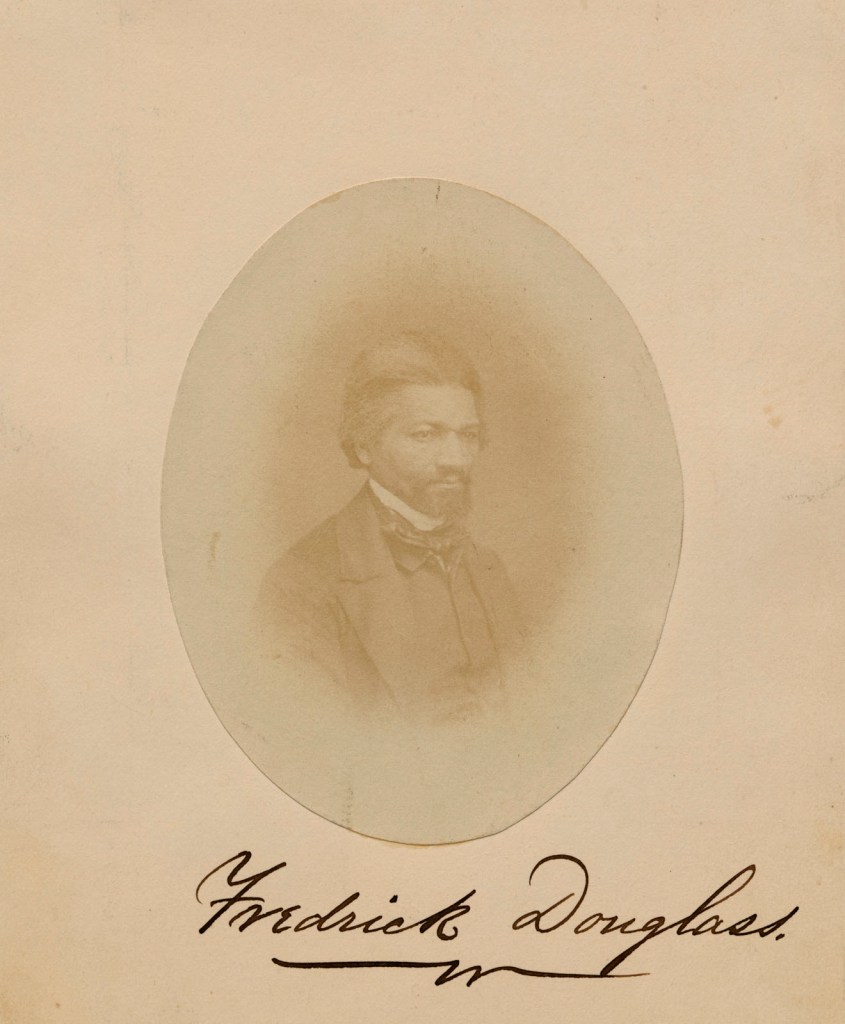

Frederick Douglass

c. 1841

Sixth-plate daguerreotype

Collection of Gregory French

In this first known photographic image of Douglass, taken only one year after the first commercial daguerreotype studio opened in the United States, he appears somewhat dazed or “statue-like,” as he might have said. In 1841, the exposure time for a daguerreotype of this size could run up to fifteen seconds, depending on the time of day and the amount of available daylight in the daguerreotypist’s studio.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

I seem to be envisioning the nineteenth-century at the moment, which is a condition entirely more pleasurable than contemplating the dreadful state of the world at the moment with its environmental desecration, greed, killing of animal and human life and the unconscionable conduct of governments. Ego, greed, religion, power, masculinity, war, nationalism, possession. A toxic mix.

Here we have photographs of a majestic human being, a former slave, social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman – who fought for freedom, who fought against discrimination and racism. And still it goes on today…

“A new memorial to Emmett Till was dedicated on Saturday in Mississippi after previous historical markers were repeatedly vandalized. The new marker is bulletproof.

Till, 14, was kidnapped, beaten and killed in 1955, hours after he was accused of whistling at a white woman. His body was found in a river days later. An all-white jury in Mississippi acquitted two white men of murder charges…

This is the fourth historical marker at the site. The first was placed in 2008. Someone tossed it in the river. The second and third signs were shot at and left riddled with bullet holes. The new 500lb steel sign has a glass bulletproof front.”1

His mother, Mamie Till Mobley, held an open casket funeral in Chicago to let the world see how badly her son had been beaten and mutilated. “There was just no way I could describe what was in that box. No way. And I just wanted the world to see.”

At the end I’ll be glad when I have left this world because I am so disappointed with the human race. High hopes indeed.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Associated Press. “Emmett Till: new memorial to murdered teen is bulletproof,” on The Guardian website Sun 20 Oct 2019 [Online] 06/04/2024

Many thankx to the National Portrait Gallery for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The bullet-riddled historical sign for Emmett Till, the Chicago teenager whose 1955 slaying helped propel the civil rights movement

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Unidentified artist (formerly attributed to Elisha Livermore Hammond)

Frederick Douglass

c. 1845

Oil on canvas

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Frederick Douglass became the most influential African American of the nineteenth century by turning his life into a testimony on the evils of slavery and the redemptive power of freedom. After he escaped from bondage in 1838, Douglass quickly emerged as an outspoken advocate for equality and abolition. Aware of the power of telling one’s own story, he frequently spoke about his life, published three genre-defining autobiographies, and founded the influential newspaper, The North Star, in 1847. Douglass also posed for countless photographs, which he considered less susceptible to artists’ racial prejudices.

This painting was likely based on the engraved frontispiece of Douglass’s first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), a gripping account of his struggle for freedom. In My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), Douglass went on to address the psychology of slavery and the racism that continued to define the lives of the newly free.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

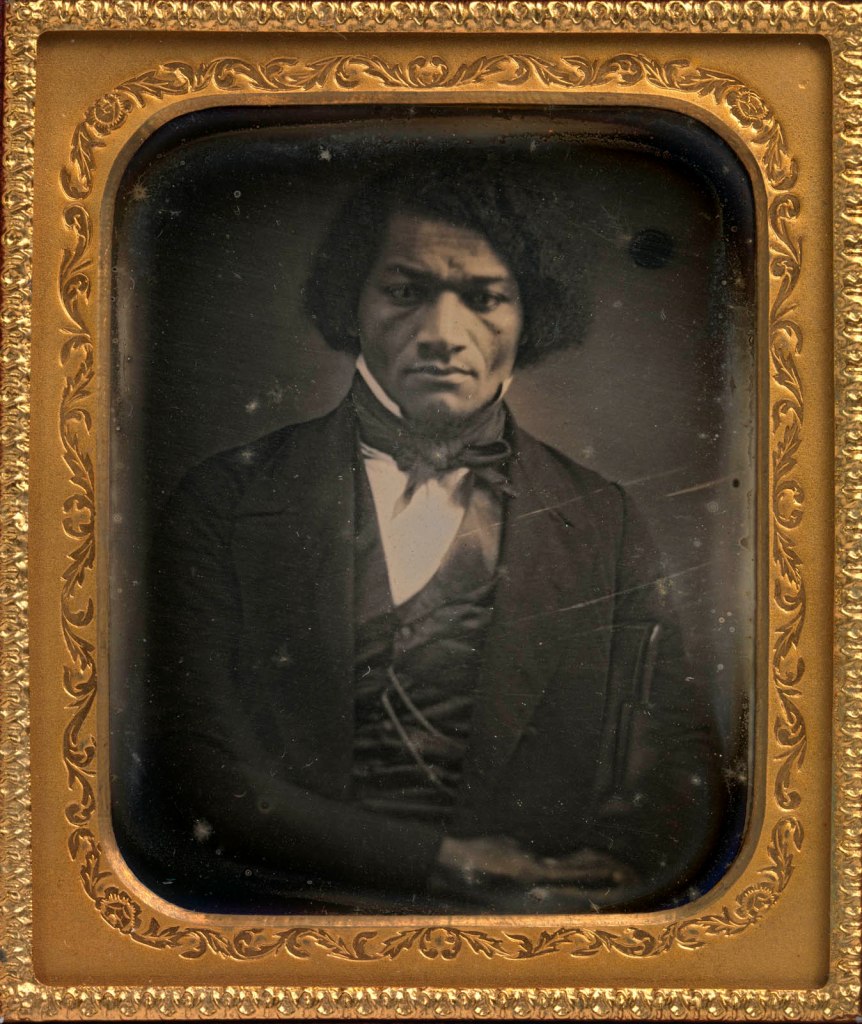

Southworth & Hawes (active 1843–1862)

Frederick Douglass

c. 1845

Whole-plate daguerreotype

Onondaga Historical Association Museum, Syracuse, NY

Douglass likely sat for this daguerreotype in the Boston studio of Southworth & Hawes before he left for England in August 1845. The Twelfth National Anti-Slavery Bazaar, held at Faneuil Hall in December 1845, offered for sale “an excellent Daguerreotype of Frederick Douglass,” according to The Liberator (January 23, 1846). The daguerreotype was “the gift of Mr. Southworth” and “elicited much attention.” John Chester Buttre created an engraving from the daguerreotype, which appeared in Autographs for Freedom (1854), a gift book edited by Douglass’s friend Julia Griffiths to raise money for his North Star newspaper.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

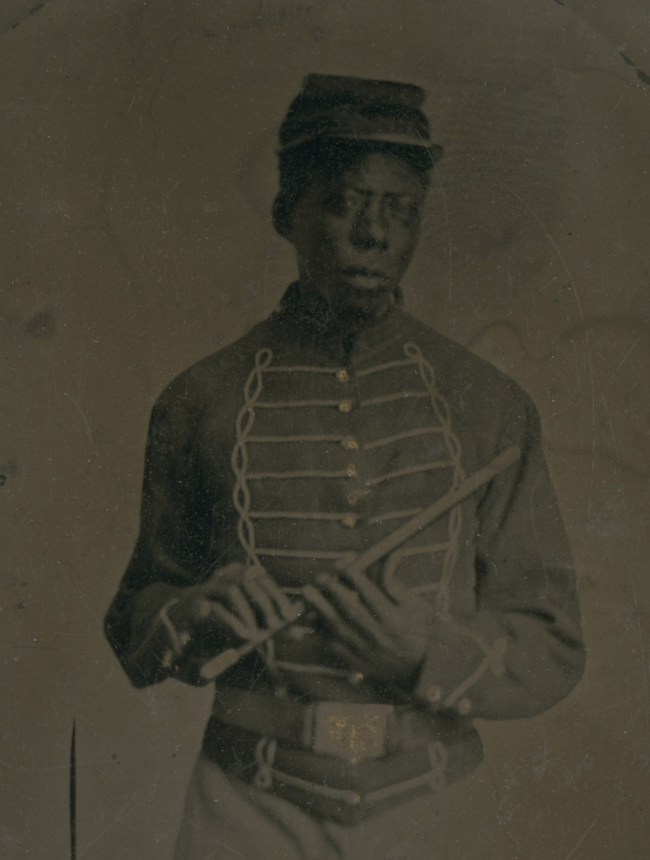

Southworth & Hawes (active 1843–1862)

Frederick Douglass (detail)

c. 1845

Whole-plate daguerreotype

Onondaga Historical Association Museum, Syracuse, NY

Augustus Washington (American, c. 1820–1875)

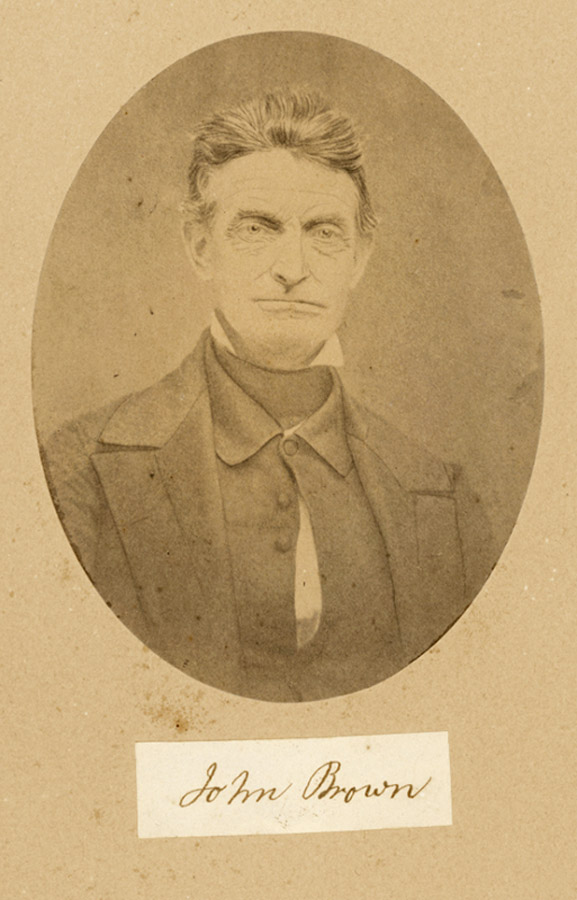

John Brown 1800-1859

c. 1846-1847

Quarter-plate daguerreotype

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; purchased with major acquisition funds and with funds donated by Betty Adler Schermer in honor of her great grandfather, August M. Bondi

One of the nation’s first African American daguerreotypists, Augustus Washington was also a prominent abolitionist in Hartford, Connecticut, when he made this portrait of the militant abolitionist John Brown. At the time, Brown was working to establish a “Subterranean Pass Way,” a network of armed men in the Alleghenies for conducting fugitives to freedom in Canada.

In Washington’s daguerreotype, Brown apparently holds the Pass Way flag and pledges allegiance to his scheme, which never materialised. In 1853, Washington and his family emigrated to Liberia, the former West African colony founded by the American Colonization Society, which gained independence in 1847.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

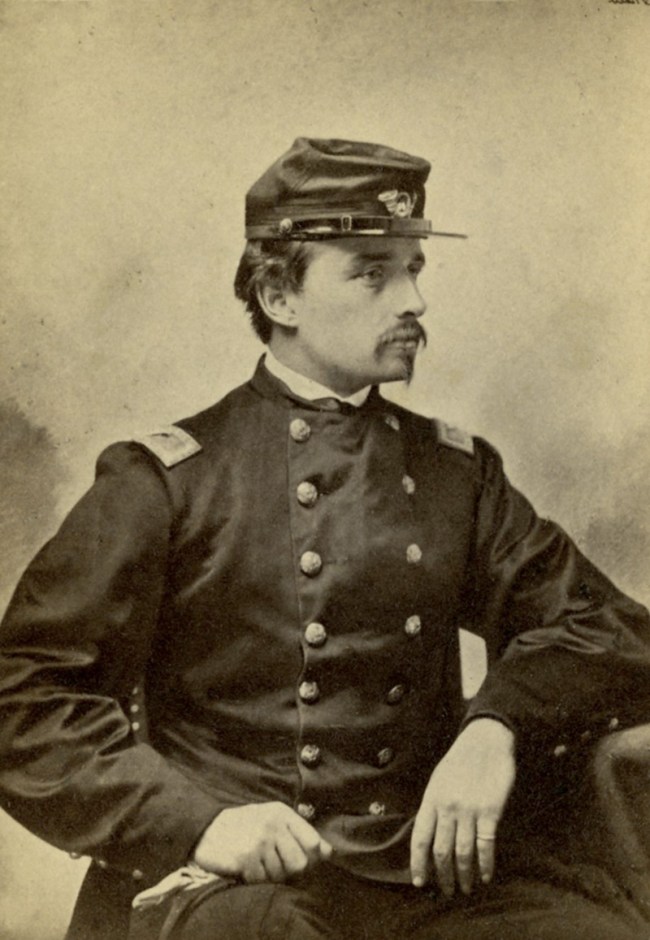

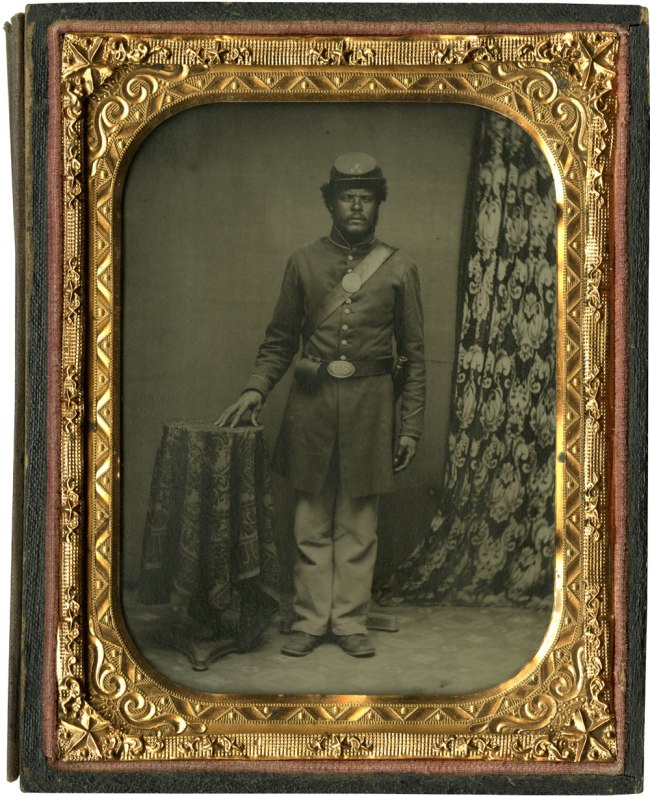

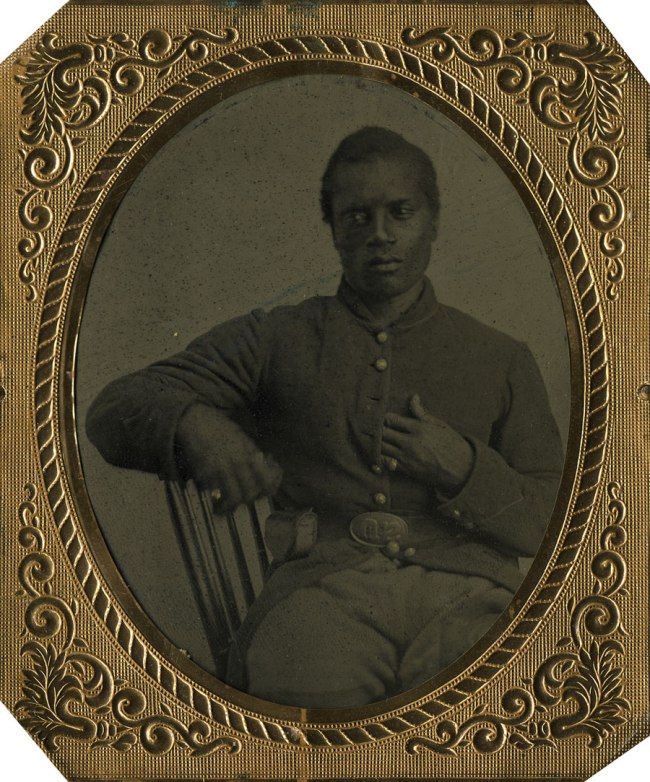

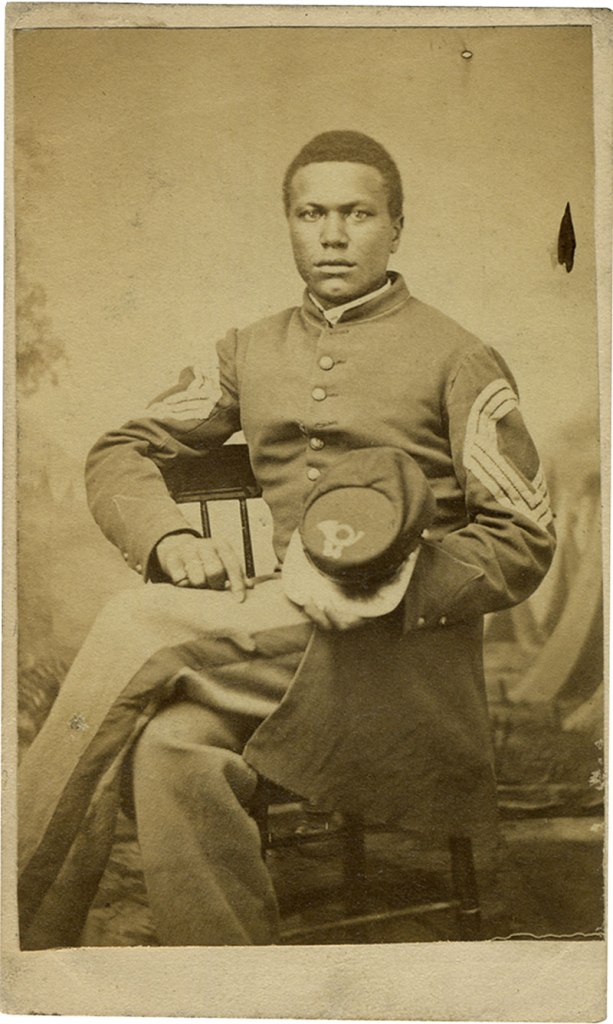

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), the preeminent African American voice of the nineteenth century, is remembered as one of the nation’s greatest orators, writers, and picture makers. Born on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1818, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was the son of Harriet Bailey, an enslaved woman, and an unknown white father. He escaped bondage in 1838 and changed his surname to Douglass.

Over six decades, Douglass published three autobiographies, hundreds of essays, and a novella; delivered thousands of speeches; and edited the longest-running Black newspaper in the nineteenth century, The North Star (later Frederick Douglass’ Paper and Douglass’ Monthly). During the Civil War, he befriended and advised President Abraham Lincoln and met every subsequent president through Grover Cleveland. He was also the first African American to receive a federal appointment requiring Senate approval (U.S. Marshal of the District of Columbia).

Douglass became the most photographed American of the nineteenth century and remains a public face of the nation. As an art critic, he wrote extensively on portrait photography and understood its power. He explained how this “true art” (as opposed to pernicious caricatures) captured the essential humanity of each subject. True art was an engine of social change, he argued, and true artists were activists: “They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavour to remove the contradiction.”

Curatorial Statement

Organised into seven sections, this exhibition highlights the long arc and significance of Frederick Douglass’s life: from slave and fugitive to internationally acclaimed abolitionist, women’s rights activist, and statesman after the Civil War. We come to recognise his influences in the Civil War and postwar eras; and the significance of his afterlife, in which his portraits and writings continue to inspire people to seek “all rights for all,” one of his mottos. The range of objects shown here reflects Douglass’s openness to new forms of media and technology to advance the cause of human rights.

John Stauffer, the Sumner R. and Marshall S. Kates Professor of English and of African and African American Studies, Harvard University

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

Douglass’ ascension into the most preeminent African American voice in the 1800s and one of the handful of most influential and famous Americans in the nation’s history owes itself equally to his merits and good fortune.

“Douglass had an extraordinary work ethic, he was immensely curious and dedicated,” Stauffer explained. “And physically strong and tall – over six feet, a half-foot taller than the average man – which helped him survive slavery.”

Size does matter. George Washington and Abraham Lincoln were also comparative giants for their day. American presidents, on average, stand a great deal taller, literally, than the average citizen.

Douglass’ physical size and strength allowed him to outlast a sadistic “slave breaker,” Edward Covey, in a protracted fight as a teen. After suffering numerous whippings, Douglass stood up to the man. As long as he lived, he referred to the fight as the turning point in his life as a slave.

“He was also lucky to have been born and raised in the upper South and not sold into the Deep South or murdered for his rebelliousness as a slave and his constant battles against slavery and racism as a free man,” Stouffer added. “Had he been born in the Deep South, where most enslaved people lived, his chances of escaping to free soil would have been almost nil.”

Douglass’ circumstances were hardly favourable, but he did win something of a genetic and geographic lottery at birth.

He also caught a rare break, learning to read and write as a young boy, skills most slaveowners prohibited.

“In Baltimore, Douglass asked his mistress, Sophia Auld, to teach him to read, which she did, having never overseen an enslaved person before,” Stouffer said. “Her husband, Hugh Auld, found out and told her in front of Douglass, ‘if you learn him to read, he’ll want to know how to write; and this accomplished, he’ll be running away from himself.’ Hearing this, Douglass ‘understood the direct pathway to freedom,’ as he said.”

Chadd Scott. “Art, Activism And Frederick Douglass At National Portrait Gallery,” on the Forbes website Aug 22, 2023 [Online] Cited 21/04/2024

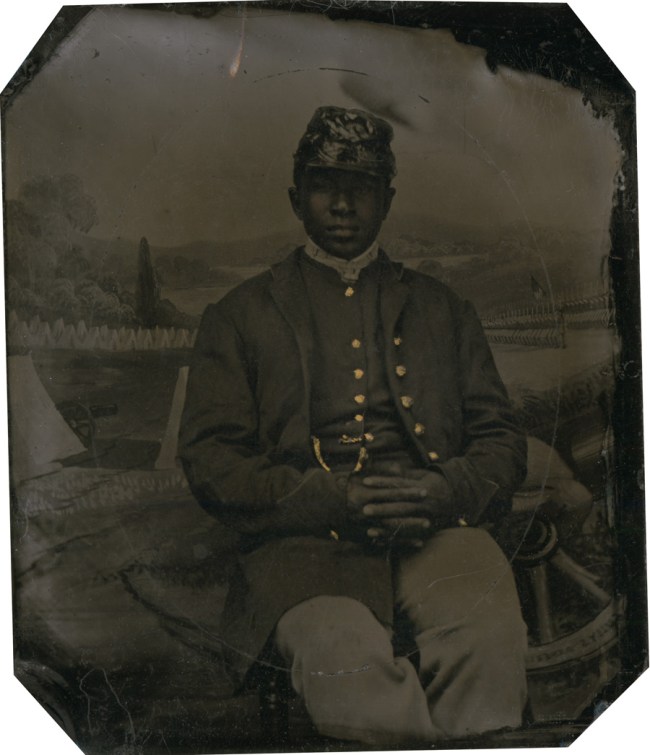

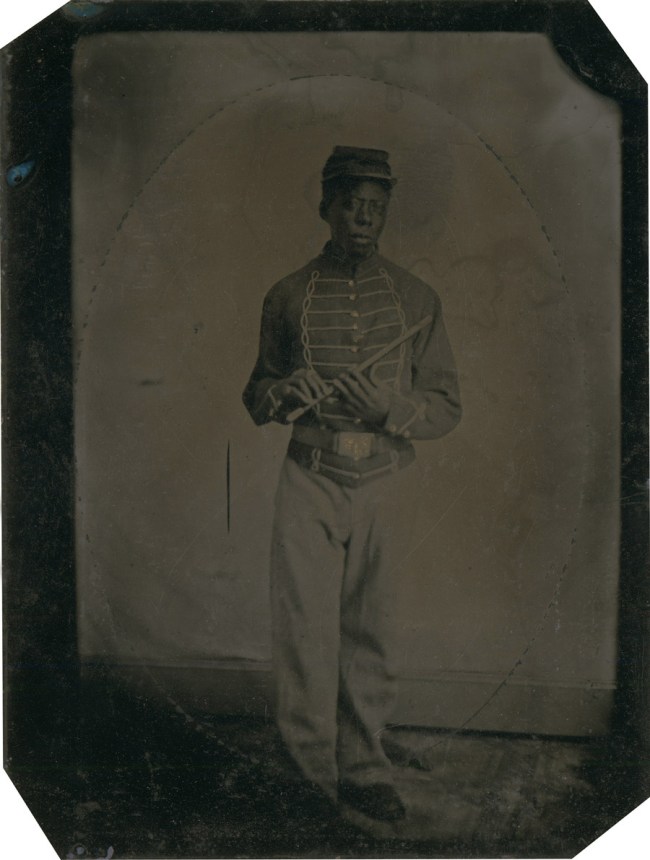

Unidentified photographer

Frederick Douglass

c. 1850 (after c. 1847 daguerreotype)

Sixth-plate daguerreotype

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

When sitting for a photograph, Douglass would pose as an artist or performer, forming part of a pas de trois with the photographer and the camera. He always dressed up and, as the activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton noted, often appeared “majestic in his wrath.”

Before the mid-1860s, Douglass typically stared into the camera lens with a dramatic look. He wanted the focus on himself. Here, he fills the frame, appearing as an accomplished, dignified activist, and projecting a visual voice of democracy. Through his images, voice, and writings, Douglass sought to “out-citizen” whites, many of whom questioned African American rights.

In the years following his escape from bondage in 1838, Frederick Douglass emerged as a powerful and persuasive spokesman for the cause of abolition. Douglass’s effectiveness as an antislavery advocate was due in large measure to his firsthand experience with the evils of slavery and his extraordinary skill as an orator whose “electrifying eloquence” astonished and enthralled his audiences. Convinced that a peaceful end to slavery was impossible, Douglass embraced the Civil War as a fight for emancipation and called for the enlistment of black troops. Throughout the decades that followed, he remained a tireless champion for civil rights.

In 1845, when the publication of his Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass revealed biographical details that could have led to his capture as a fugitive from slavery, Douglass left the United States for an extended stay in Great Britain. He was warmly welcomed by British abolitionists, who raised the funds to purchase his freedom, thereby enabling Douglass to return to the United States in 1847 as a free man. In this daguerreotype, believed to date from the time of his return, Douglass confronts the camera with an intensity that became the hallmark of his photographic portraits.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

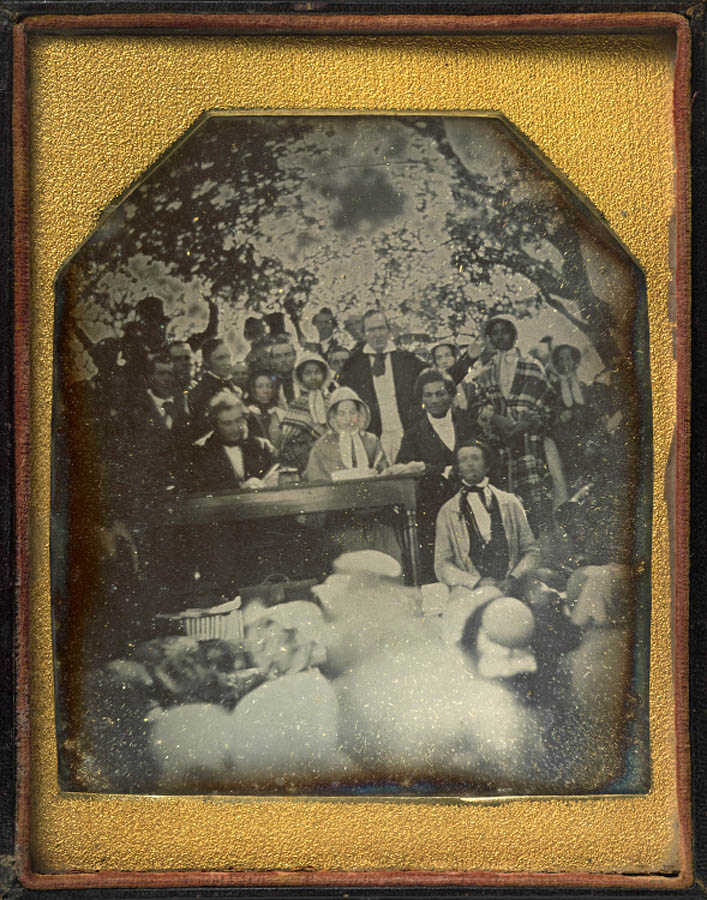

Ezra Greenleaf Weld (American, 1801-1874)

Fugitive Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, New York

1850

Half-plate copy daguerreotype

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Set Charles Momjian

On August 21, 1850, two days after the Senate passed the Fugitive Slave Act [Passed on September 18, 1850 by Congress, The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was part of the Compromise of 1850. The act required that slaves be returned to their owners, even if they were in a free state. The act also made the federal government responsible for finding, returning, and trying escaped slaves], about two thousand abolitionists convened near Gerrit Smith’s home. Douglass presided as president. Participants approved Smith’s “Letter to the American Slaves,” urging captives to avenge their enslavers. “You are prisoners of war in an enemy’s country,” Smith declared.

Here, Douglass sits at the edge of the table next to Theodosia Gilbert, the fiancée of William Chaplin, who was in prison for aiding fugitives. Behind Douglass stands Gerrit Smith [see photo below], in mid-speech, gesticulating. On either side of Smith, in checkered shawls and day bonnets, are Mary and Emily Edmonson, whose freedom had been orchestrated by Chaplin.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

Ezra Greenleaf Weld, known simply as “Greenleaf,” operated a daguerreotype studio in Cazenovia, New York, during a time of intense social and political turmoil. He opened his first studio in his home in 1845, when America began to witness the volatile events that led to the Civil War. At that time, instruction manuals on the daguerreotype process were widely available, and most small towns had at least one studio. In an 1850 advertisement in his local newspaper, Greenleaf offered “Miniatures executed in the finest style, and put in Rings, Pins, Lockets and cases, of great variety size and price.”

Greenleaf seems to have been very successful with his daguerreotype business. By 1851 he had leased new quarters on the top floor of a building, where he placed a skylight to receive northern light for his studio sessions. During the Civil War years, he made numerous pictures in and around Cazenovia.

Text from the J. Paul Getty Museum website

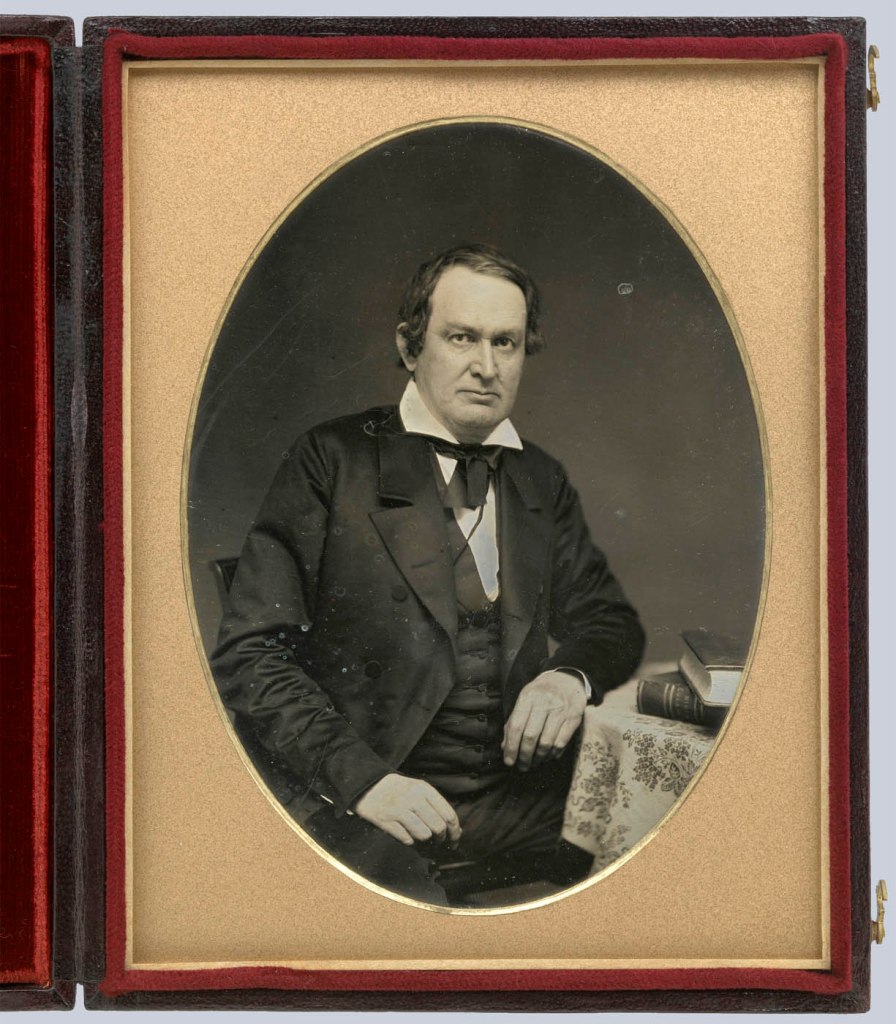

Southworth & Hawes (active 1843–1862)

William Lloyd Garrison 1805-1879

c. 1851

Half-plate daguerreotype

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

After escaping enslavement, Douglass subscribed to William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper, The Liberator, and read it as devoutly as his bible. “The paper became my meat and drink,” he recalled.

Garrison promoted Douglass’s 1845 autobiography, which made him famous and prompted him to flee to the British Isles to avoid capture and re-enslavement. British friends then purchased his freedom, and he returned to the United States in 1847, a free man. Wanting to launch his own paper, Douglass soon moved his family to Rochester, New York, a railroad and antislavery hub that lacked an abolitionist paper. The move ruptured his friendship with Garrison until after the Civil War.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery will present One Life: Frederick Douglass, an exhibition exploring the life and legacy of one of the 19th century’s most influential writers, speakers and intellectuals. Douglass was a radical activist who devoted his life to abolitionism and rights for all. This exhibition shows the intimate relationship between art and protest through prints, photographs and ephemera. One Life: Frederick Douglass is guest curated by John Stauffer, the Sumner R. and Marshall S. Kates Professor of English and African and African American Studies at Harvard University, and consulting curator Ann Shumard, the National Portrait Gallery’s senior curator of photographs.

“Frederick Douglass was the preeminent African American voice of the 19th century and among the nation’s greatest orators, writers and picture-makers,” Stauffer said. “Born into slavery, he became a leading abolitionist, civil rights activist and the most photographed American of the 19th-century, a public face of the nation. This comprehensive exhibition includes objects from all phases of his life as a way to highlight the power of his remarkable impact. It explores his friendship with President Abraham Lincoln, for example, as well as his enduring influence on artists and activists in the 20th and 21st centuries.”

Douglass was born on the Eastern shore of Maryland in 1818. Having escaped slavery in 1838, he traveled to New York, where he married Anna Murray. After the couple moved to Massachusetts, he began attending abolitionist meetings. Douglass went on to publish three autobiographies and a novella, deliver thousands of speeches and edit the longest continually running Black newspaper of the 19th century, The North Star (later Frederick Douglass’ Paper and Douglass’ Monthly). As a political insider and policy influencer during the Civil War, he befriended and advised President Abraham Lincoln. Douglass changed traditional rules of representation by explaining how “true art” could be an engine of social change.

The exhibition will showcase over 35 objects, including the ledger documenting Douglass’ birth in February 1818; a pamphlet of his “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” oration; two of his three autobiographies – My Bondage and My Freedom and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself; a letter from Douglass to Lincoln; portraits of activists in Douglass’ circle, such as Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth; portraits by the prominent Black photographers Augustus Washington and Cornelius Marion Battey; and portraits of the Black leaders Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes, all of whom carried on his legacy.

Press release from the National Portrait Gallery

Ezra Greenleaf Weld (American, 1801-1874)

Gerrit Smith 1797-1874

c. 1854

Two-thirds daguerreotype

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of an anonymous donor

Gerrit Smith, the upstate New York abolitionist and philanthropist, was a close friend of Douglass from the late 1840s to the Civil War. In 1846, Smith gave away 120,000 acres of land in the Adirondacks, known as “Timbuctoo,” to three thousand Black residents of New York State. Smith welcomed Douglass to New York with a deed for forty acres and provided crucial financial support to his newspaper. “You not only keep life in my paper but keep spirit in me,” Douglass wrote. Smith helped convert Douglass into a political abolitionist, one who interpreted the Constitution as an antislavery document.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

Unidentified photographer

John Brown 1800-1859

c. 1857 (after c. 1855 daguerreotype)

Salted paper print

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Douglass described John Brown as someone who, “though a white gentleman, is in sympathy a black man, and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.” They became friends, and in 1859, Brown urged Douglass to join him in raiding the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. Douglass, however, refused and told Brown he thought he was entering a “steel trap.” Brown and sixteen others were killed, either during the raid or after they were found guilty of treason. Douglass later credited Brown with starting the war that ended slavery.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

Frederick Douglass believed that Brown’s “zeal in the cause of my race was far greater than mine – it was as the burning sun to my taper light – mine was bounded by time, his stretched away to the boundless shores of eternity. I could live for the slave, but he could die for him.”

Douglass, Frederick (1881). John Brown. An Address at the Fourteenth Anniversary of Storer College, May 30, 1881. Dover, New Hampshire: Dover, N. H., Morning Star job printing house. p. 9. Retrieved March 9, 2022

Unidentified photographer

Frederick Douglass

c. 1860

Salted paper print

Image: 6 × 4.5cm (2 3/8 × 1 3/4″)

Sheet: 10.1 × 7.9cm (4 × 3 1/8″)

Mount: 17 × 13.6cm (6 11/16 × 5 3/8″)

Mat: 45.7 × 35.6cm (18 × 14″)

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Douglass’s visual persona continually evolved, which undermined one of the key intellectual foundations of chattel slavery and racism that cast the self as fixed, unable to rise. Perhaps the most noticeable markers of Douglass’s continual evolution are his hairstyle and facial hair. In this salted paper print, he experiments with a mid-scalp part, unique among the 168 separate photographs. Five years later, in a carte de visite, he sports a ponytail, also distinct from his typical hairstyle.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

Douglass’ words were powerful; his image, arguably, more so.

“Douglass, along with most Americans, believed that photography was a ‘truthful’ representation and the great democratic art,” Stouffer explained. “He also recognised that the sitter had agency in the outcome of a photographic portrait. He understood his role as an artist or performer, part of a pas de trois with the photographer and the camera. He always dressed up. His photographic portraits, along with those of numerous other African Americans, starkly contrasted the racist caricatures of Blacks created by whites.”

A long American tradition of white artists caricaturing African Americans in prints and paintings influenced public perception. White painters in the antebellum era almost always cast the devil as a Black man. Monkeys and happy slaves were other tropes.

Douglass, meanwhile, always presented himself, in dress, pose, and expression, as a dignified and respectable citizen.

“Photography was a truth-telling medium he emphasised. It bore witness to African Americans, and all humans, essential humanity, and it countered the racist caricatures by whites drawing freehand,” Stouffer said. “Douglass argued that photography inspired people to eradicate the sins of their society. It led them to activism. It stemmed from the power of imagination, which allowed people to appreciate photographs as accurate representations of some greater reality. It encouraged them to realise their ideals in an imperfect world.”

As Douglass put it: “Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers – and this ability is the secret of their power and of their achievements. They see what ought to be in the reflection of what is, and endeavour to remove the contradiction.”

This is a key message of the exhibition.

“Poets, prophets, and reformers were artists and activists. Activism inspired art and vice versa. Poets, prophets, and reformers saw their community or nation as it was – with all its gross inequalities, injustices, and prejudices – and they contrasted it with what ought to be. The contradiction inspired them to remove structural inequalities, injustices, and prejudices,” Stouffer explained. “Douglass and most other abolitionists, along with many antislavery advocates, considered themselves poets, prophets, and reformers. As a group, they sat for their photographic portraits with greater frequency, distributed them more effectively, and were more taken with photography, than other groups.”

Douglass went so far as to say that “the moral and social influence of pictures” was more important than “the making of its laws.”

Chadd Scott. “Art, Activism And Frederick Douglass At National Portrait Gallery,” on the Forbes website Aug 22, 2023 [Online] Cited 21/04/2024

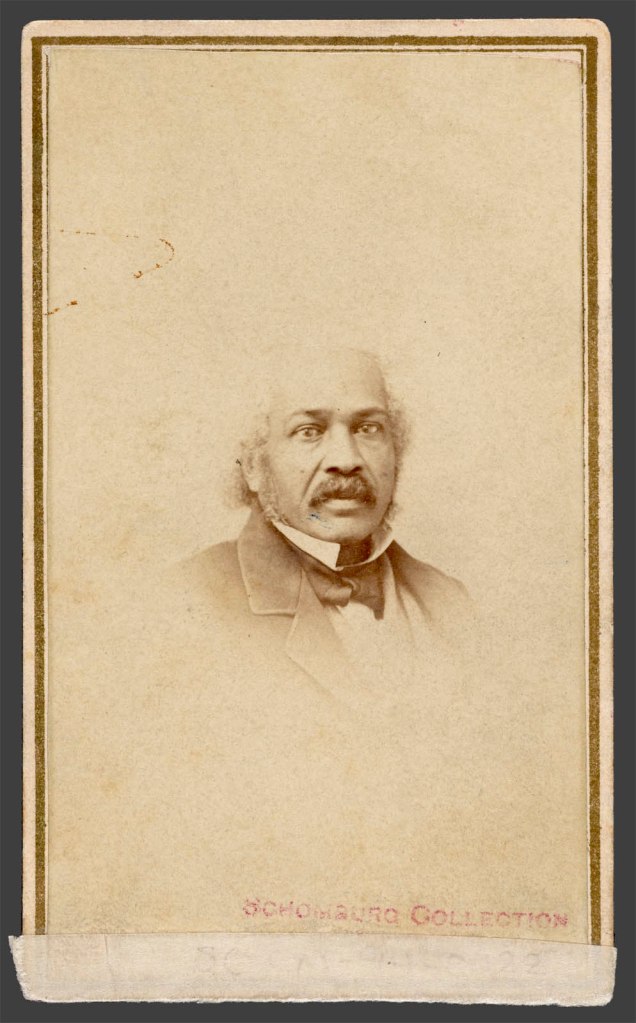

Johnson, Williams &. Co. (active 1860s and 1870s)

James McCune Smith 1813-1865

c. 1860

Albumen silver print

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division; The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

James McCune Smith (April 18, 1813 – November 17, 1865) was an American physician, apothecary, abolitionist and author. He was the first African American to earn a medical degree. His M.D. was awarded by the University of Glasgow in Glasgow, Scotland. After his return to the United States, he also became the first African American to run a pharmacy in the nation.

In addition to practicing as a physician for nearly 20 years at the Colored Orphan Asylum in Manhattan, Smith was a public intellectual: he contributed articles to medical journals, participated in learned societies, and wrote numerous essays and articles drawing from his medical and statistical training. He used his training in medicine and statistics to refute common misconceptions about race, intelligence, medicine, and society in general. He was invited as a founding member of the New York Statistics Society in 1852, which promoted a then new science. Later he was elected as a member in 1854 of the recently founded American Geographic Society. He was never admitted to the American Medical Association or local medical associations,[1] very likely as a result of the systemic racism that Smith confronted throughout his medical career.

He has been most well known for his leadership as an abolitionist: a member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, with Frederick Douglass he helped start the National Council of Colored People in 1853, the first permanent national organisation for blacks. Douglass called Smith “the single most important influence on his life.” Smith was one of the Committee of Thirteen, who organised in 1850 in Manhattan to resist the newly passed Fugitive Slave Law by aiding refugee slaves through the Underground Railroad. Other leading abolitionist activists were among his friends and colleagues. From the 1840s, Smith lectured on race and abolitionism and wrote numerous articles to refute racist ideas about black capacities.

Both Smith and his wife were of mixed African and European descent. As he became economically successful, Smith built a house in a mostly white neighbourhood; in the 1860 census he and his family were classified as white, along with their neighbours. (In the census of 1850, while living in a predominately African-American neighbourhood, they had been classified as mulatto.) Smith served for nearly 20 years as the physician at the Colored Orphan Asylum in New York. After it was burned down in July 1863 by a mob in draft riots in Manhattan, in which nearly 100 blacks were killed, Smith moved his family and practice to Brooklyn for their safety. Many other blacks left Manhattan for Brooklyn at the same time. The parents stressed education for their children. In the 1870 census, his widow and children continued to be classified as white.

Text from the Wikipedia website

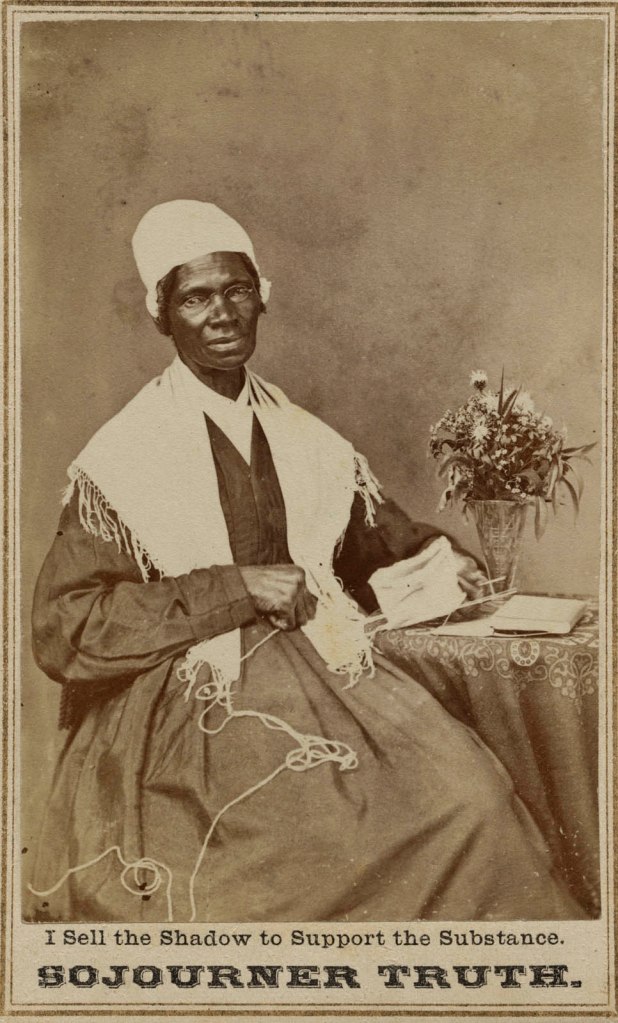

Unidentified photographer

Sojourner Truth c. 1797-1883

1864

Albumen silver print

Image/Sheet: 8.7 × 5.6cm (3 7/16 × 2 3/16″)

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Sojourner Truth was possibly more famous for her carte-de-visite photographs than for her actual presence at abolition meetings. Her carefully chosen images made her a familiar figure to millions of viewers. They depicted a respectable matron. Truth’s famous maxim that she included with her portrait, “I sell the shadow to support the substance,” links her image (shadow) to her actual self (substance) and to the growing demand for photographs during the war years.

Truth’s image becomes an extension of herself and her nation. The yarn forms the contours of the eastern United States, with Florida’s panhandle and Texas clearly visible. As a representative American woman, Truth’s piety, simplicity, and abolitionism were shaping the United States.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

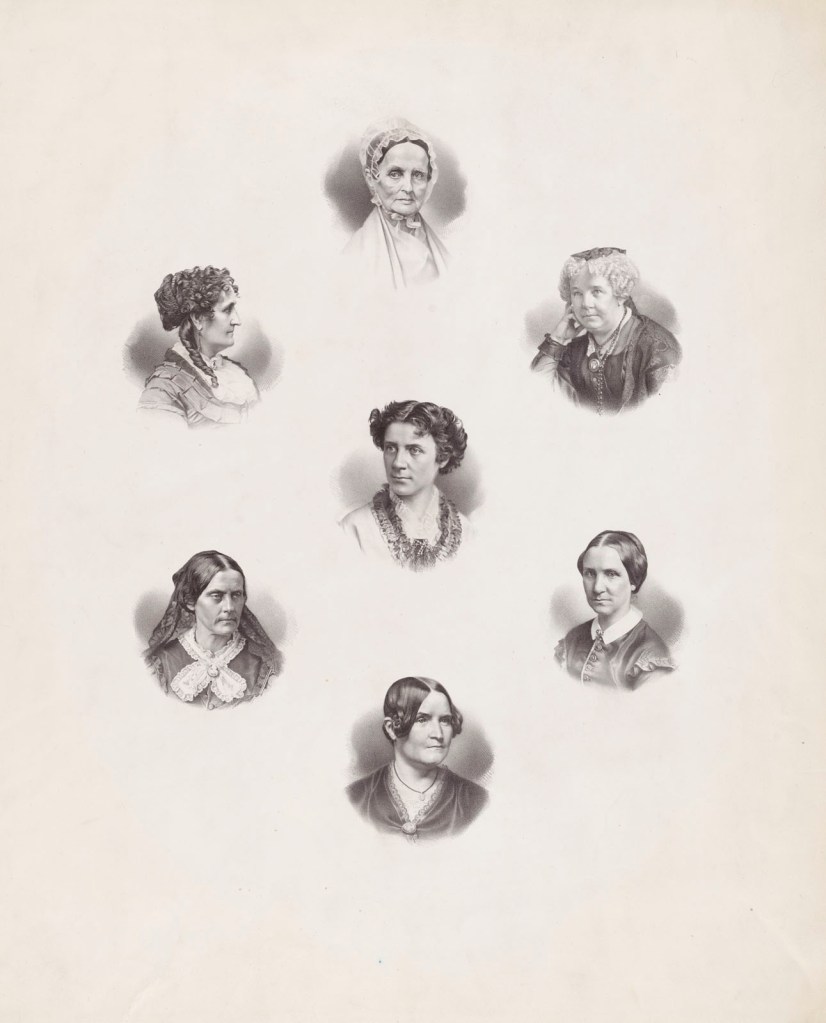

L. Schamer (active c. 1870)

Louis Prang Lithography Co. (active 1856-1899)

Representative Women

1870

Lithograph

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

This portrait unites seven leading female suffragists. Clockwise from the top are portraits of Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Livermore, Lydia Maria Child, Susan B. Anthony, and Sara Jane Lippincott, who surround Anna Dickinson, the most popular woman on the lecture circuit; in a sense, Douglass’s counterpart. The visual power of the image stems from its ability to reveal both the cohesiveness of the movement and the strong personalities within it.

Douglass knew these women and, as a leading male advocate for women’s rights, often collaborated with them and attended their conventions. But when Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment in 1869, granting suffrage to Black men but not to women, their cohesion crumbled. Anthony and Stanton argued that white women should have suffrage before Black men. Douglass supported the amendment but continued to advocate for women’s suffrage.

Between 1860 and 1880, it became common for American reformers to gather on stages – then called lyceums – to promote abolition, temperance, education reform, and women’s rights. Lyceum associations allowed suffragists to speak. In their lectures, suffragists addressed men and women of diverse backgrounds – across state, racial, and economic divides – and reached wider audiences than through women’s organisations alone.

Representative Women is a combinative portrait that brings together seven women who were active on the lecture circuit. The visual power of the image stems from its ability to reveal both the cohesiveness of the movement and the strong individual personalities within it. Clockwise from the top are portraits of Lucretia Coffin Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Livermore, Lydia Maria Francis Child, Susan B. Anthony, and Sara Jane Lippincott, who surround the central figure of Anna Elizabeth Dickinson. At the time, Dickinson was more popular than Mark Twain and held the distinction of being the highest paid woman on the lecture circuit.

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

NOT IN THE EXHIBITION BUT IN THE NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY COLLECTION

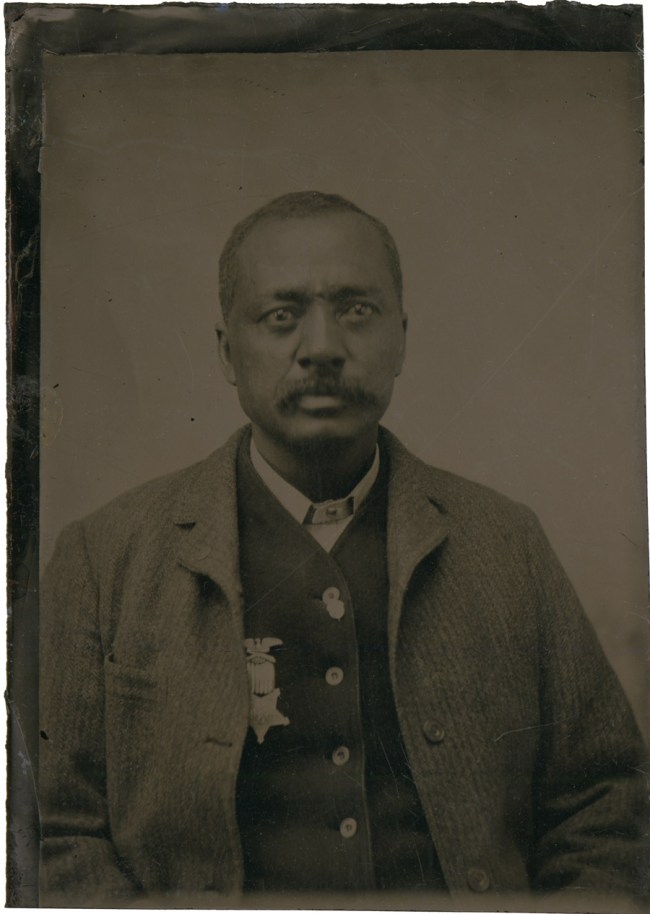

Unidentified photographer

Frederick Douglass

1856

Quarter-plate ambrotype

Image/Sight: 8.8 × 6.7cm (3 7/16 × 2 5/8″)

Mat (brass): 10.8 × 8.3cm (4 1/4 × 3 1/4″)

Case open: 12 × 19.2 × 1.3cm (4 3/4 × 7 9/16 × 1/2″)

Case closed: 12 × 9.5 × 1.9cm (4 3/4 × 3 3/4 × 3/4″)

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor

In the years following his escape from bondage in 1838, Frederick Douglass emerged as a powerful and persuasive spokesman for the cause of abolition. His effectiveness as an antislavery advocate was due in large measure to his firsthand experience with the evils of slavery and his extraordinary skill as an orator. His “glowing logic, biting irony, melting appeals, and electrifying eloquence” astonished and enthralled his audiences. As this ambrotype suggests, Douglass’s power was also rooted in the sheer impressiveness of his bearing, which abolitionist and activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton likened to that of “an African prince, majestic in his wrath.”

Text from the National Portrait Gallery website

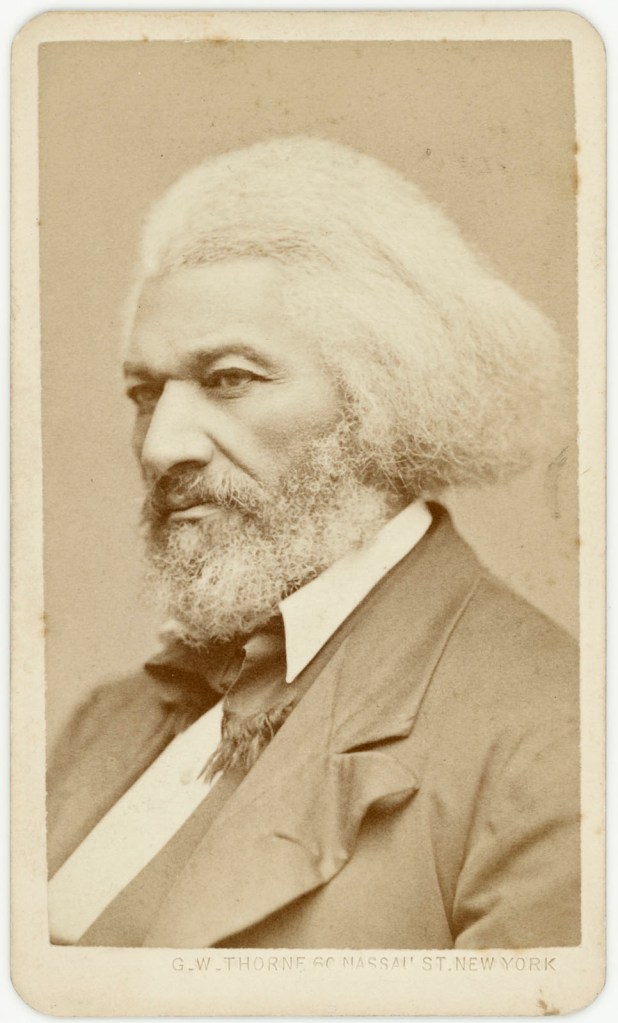

George Francis Schreiber (American, 1803-1892)

Frederick Douglass

1870

Albumen silver print

Image/Sheet: 9.4 x 5.9cm (3 11/16 x 2 5/16″)

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Donald R. Simon

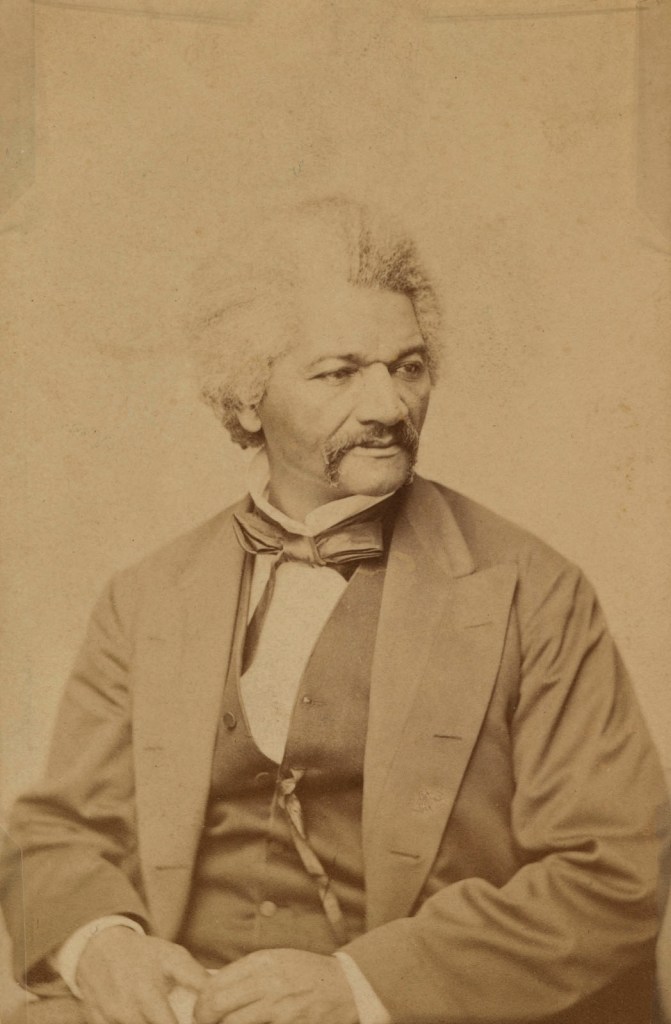

George Kendall Warren (American, 1834-1884)

Frederick Douglass

1876

Albumen silver print

Image/Sheet: 9.7 × 5.7cm (3 13/16 × 2 1/4″)

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

8th and F Sts NW

Washington, DC 20001

Opening hours:

11.30am – 7.00pm daily

![J[eremiah] Gurney (American) 'Untitled [Cross-eyed man in three-quarter profile]' Nd J[eremiah] Gurney (American) 'Untitled [Cross-eyed man in three-quarter profile]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-half-plate-jeremiah-gurney-at-349-broadway-new-york-orig.jpg?w=750)

![J[eremiah] Gurney (American) 'Untitled [Cross-eyed man in three-quarter profile]' Nd J[eremiah] Gurney (American) 'Untitled [Cross-eyed man in three-quarter profile]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-half-plate-jeremiah-gurney-at-349-broadway-new-york-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Group of three men]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Group of three men]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-unsigned-unusual-period-frame-of-cast-thermoplastic-circa-1850-web.jpg?w=746)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man on crutches]' c. 1850-1860s Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man on crutches]' c. 1850-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/man-on-crutches-sixth-plate-ambrotype-1850-60s-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) Untitled [Man with pistols] c. 1850-1860s Unknown photographer (American) Untitled [Man with pistols] c. 1850-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/man-with-pistols-sixth-plate-daguerreotype-1850-60s-orig.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) Untitled [Man with pistols] c. 1850-1860s Unknown photographer (American) Untitled [Man with pistols] c. 1850-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/man-with-pistols-sixth-plate-daguerreotype-1850-60s-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man, possibly a sailor, wearing hoop earrings]' Nd Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man, possibly a sailor, wearing hoop earrings]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/man-possibly-a-sailor-wearing-hoop-earrings-orig.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man, possibly a sailor, wearing hoop earrings]' Nd Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man, possibly a sailor, wearing hoop earrings]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/man-possibly-a-sailor-wearing-hoop-earrings-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [African American]' c. 1850s Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [African American]' c. 1850s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-unsigned-sixth-plate-american-circa-1850s-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [African American]' c. 1850s Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [African American]' c. 1850s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-unsigned-sixth-plate-american-circa-1850s-b-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Two men in caps, elegantly dressed]' c. 1850s Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Two men in caps, elegantly dressed]' c. 1850s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/unsigned-dag-two-men-in-caps-elegantly-dressed-american-circa-1850s-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Handsome man with fifth finger ring]' c. 1850s Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Handsome man with fifth finger ring]' c. 1850s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-unsigned-1850s-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Portrait of violinist holding instrument]' c. 1855 Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Portrait of violinist holding instrument]' c. 1855](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-sixth-plate-portrait-of-violinist-holding-instrument-circa-1855-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Two men, one with trug of tools]' c. 1850-1860s Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Two men, one with trug of tools]' c. 1850-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/two-men-one-with-trug-of-tools-sixth-plate-ambrotype-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Two firemen]' c. 1850-1860s Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Two firemen]' c. 1850-1860s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/two-firemen-quarter-plate-tinted-tintype-1850-60s-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man in button braces]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man in button braces]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-unsigned-ninth-plate-american-circa-1850-web.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man in button braces]' c. 1850 Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Man in button braces]' c. 1850](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/dag-unsigned-ninth-plate-american-circa-1850-web1.jpg?w=750)

![Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Two young men with straw hats, seated beside each other]' Nd Unknown photographer (American) 'Untitled [Two young men with straw hats, seated beside each other]' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/two-young-men-with-straw-hats-web.jpg?w=929)

You must be logged in to post a comment.