Exhibition dates: 28th September 2010 – 6th February 2011

Curators: Michel Frizot and Annie-Laure Wanaverbecq

Many thankx to Jeu de Paume for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Underwater Swimmer, Esztergom

1917, printed in the 1980s

Gelatin silver print

Bibliothèque Nationale de France

André Kertész

André Kertész (Budapest, 1894 – New York, 1985) has never seen his work the subject of a real retrospective in Europe, although he donated all his negatives to the French State. However, he is one of the major photographers of the 20th century, both in terms of the richness of his work and the longevity of his career…

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Esztergom

1918

Gelatin silver print

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Tisza Szalka

1924

Vintage gelatin silver contact print

Salgo Trust for Education, New York

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Self-portrait, Paris

1927

Gelatin silver print

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Plaque cassée, Paris (Broken Plate, Paris)

1929

Gelatin silver print

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

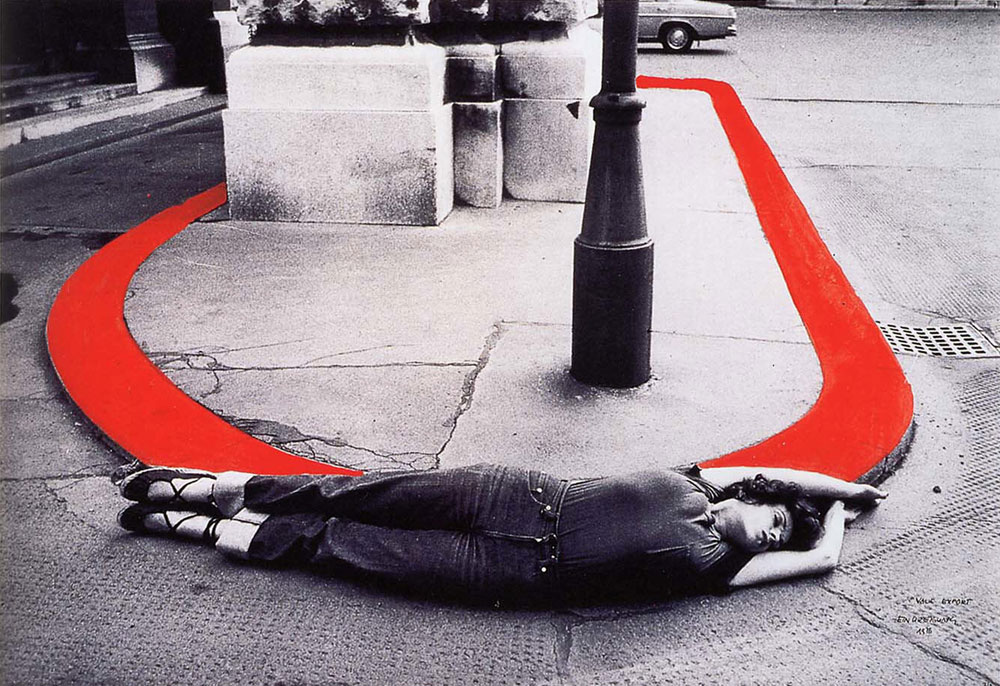

Distortion n° 41

1933

[with André Kertész selportrait]

Gelatin silver print, later print

Collection of the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris

Twenty-five years after his death, André Kertész (1894-1985) is today a world-famous photographer who produced images that will be familiar to everyone, but he has yet to receive full recognition for his personal contribution to the language of photography in the 20th century. His career spanning more than seventy years was chaotic, and his longevity was matched by an unwavering creative acuity that rendered difficult an immediate or retrospective understanding of his work.

This exhibition attempts to provide for the first time a broad and balanced view of Kertéz’s work, presenting new elements and bringing together, for the first time also, a large number of period prints (two thirds of the 300 photographs on show). Both the exhibition and the accompanying catalogue were produced in collaboration with The André and Elizabeth Kertész Foundation (New York) and the Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine (Paris), which holds Kertész’s donation to the ministère de la Culture.

An initial investigation was undertaken during his lifetime as part of preparations for the first retrospective in 1985. The book Ma France (1990) paid tribute to his French donation and celebrated his Parisian periods (1925-1936 and after 1963), and the recent catalogue for the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art (2005), Washington, provided lots of circumstantial information and new analyses. With this retrospective exhibition, which draws extensively on archive documents, we have attempted to present Kertész’s work as a whole in its homogeneity and its continuity, as he himself conceived it, reflecting closely the course of his life.

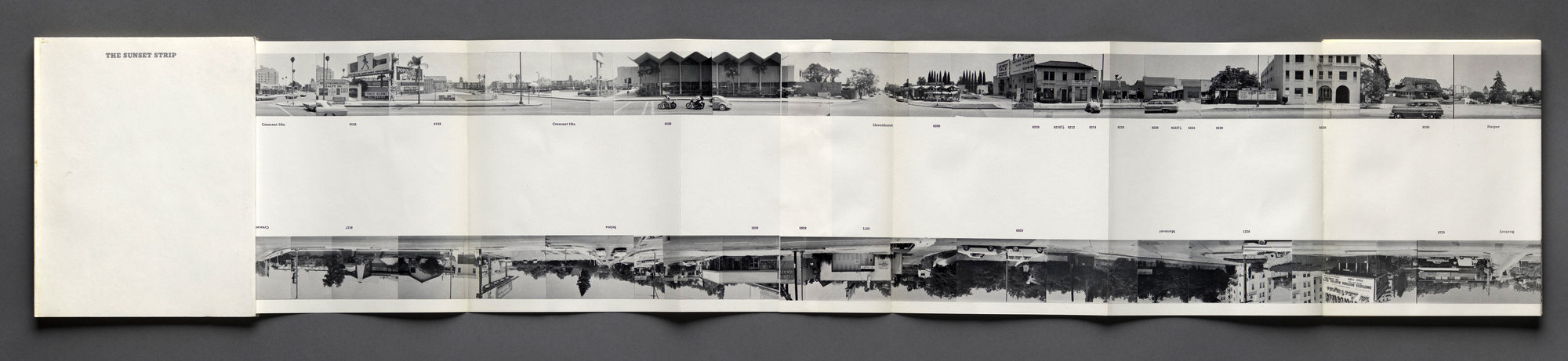

Adopting a chronological and linear exhibition layout reflecting the various periods of his creative life, punctuated by self-portraits at the entrance to each space, we have created thematic groups in the form of “cells” highlighting the unique aspects of his output: his personal photography (the photographic postcards, the Distortions), his involvement in publishing (the book Paris vu par Kertész, 1934), his recurrent creative experiments (shadows, chimneys), and the more diffuse expression of emotions (solitude). The exhibition sheds light on the importance of previously neglected or unexplored periods (his time as a soldier between 1914 and 1918, the New York period and the Polaroids of his last years). In particular, it highlights the beginnings of photojournalism in Paris in 1928, and the dissemination of his photographs in the press, which had become a professional activity for him. Thus numerous copies of magazines are presented (Vu, Art et Médecine, Paris Magazine), as are the various publications of his photo essay on the Trappist monastery in Soligny, with Kertész’s original shots.

Press release from the Jeu de Paume website

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Place de la Concorde

Paris, 1928, printed in the 1970s

Gelatin silver print

Collection of Robert Gurbo

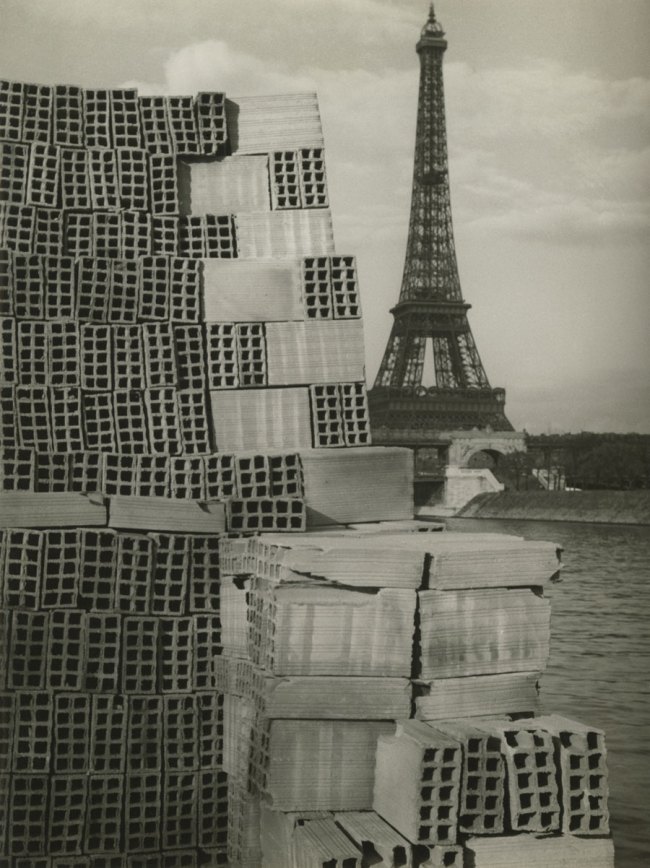

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

The Eiffel Tower, Paris

1933

Vintage gelatin silver print

Courtesy Stephen Daiter Gallery

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Elizabeth and I

1933

Gelatin silver print

A Small Journal

André Kertész (1894-1985) is today famous for his extraordinary contribution to the language of photography in the 20th century. This retrospective, which will be traveling to Winterthur, Berlin, and Budapest, marshals a large number of prints and original documents that highlight the exceptional creative acuity of this photographer, from his beginnings in Hungary, his homeland, to Paris, where between 1925 and 1936 he was one of the leading figures in avant-garde photography, to New York, where he lived for nearly fifty years without encountering the success that he expected and deserved. It pays tribute to a photographer whom Cartier-Bresson regarded as one of his masters, and reveals, despite an apparent diversity of periods and situations, themes and styles, the coherence of Kertész’s approach. It emphasises his originality and poetic uniqueness, drawing on new elements to present his oeuvre as the photographer himself conceived it, reflecting as closely as possible the course of his life. It makes full use of archive documents, focusing in particular on an area of his work that is little known (the beginnings of photo-reportage in Paris and the publication of his images in the press and books), and it analyses the circumstances surrounding his late resurgence. By exploring the recurring preoccupations and themes of Kertész’s work, it sheds light on the complex output of this unclassifiable photographer, who defined himself as an “amateur,” and in connection with whom Roland Barthes talked of a photography “that makes us think.”

Hungary 1894-1925: from Andor to André

Kertész’s youth left him with an enduring love of the countryside, animals, leisurely walks, and down-to-earth people. His sentimental nature led him to treat photography as “a little notebook, a sketchbook,” whose principal subjects were his friends, his family, his fiancée Elizabeth, and above all his younger brother, Jenö, with whom he carried out most of his early experiments in photography. Called up during the war, he continued to take photographs, capturing for the most part trivial events in the lives of the soldiers, whose situation he shared, for in spite of the context photography remained for him a way of expressing emotions. André Kertész was very independent at this time – his work diverged radically from the prevailing pictorialism of the time – and he was laying the foundations for a unique innovative photographic language. In 1914, he began photographing at night; in 1917, he took an astonishing photo of an underwater swimmer, and captured his brother “as a scherzo” in 1919. The two persons watching the Circus (1920) and The Blind Musician (1921) immediately emerged as modernist images. André Kertész’s photography was distinguished at this time by its freedom and diversity of approach, as well as its reliance on feelings and emotional bonds for inspiration.

France, 1925-1936: The Garden of André Kertész

Hard up and speaking only Hungarian, André Kertész lived in Paris amid a circle of fellow Hungarian émigrés. It was in the studio of one of them, Étienne Beöthy, that the dancer Magda Förstner, mimicking one of the artist’s sculptures, instigated the famous photograph Satiric Dancer in 1926. In the same year, when taking photographs at Mondrian’s studio, the photographer emerged as the master of a new type of unorthodox “portrait in absence.” Kertész evokes more than he shows, giving life to the inanimate, and creating a poetic language of allusive signs, both poetic and visual. During the early years of his life in Paris, he printed a large number of his images on photographic paper in postcard format (this inexpensive practice occupied a notable place in his work, because he resorted to it so persistently and with such inventiveness).

The street also provided the photographer with micro-events, fleeting associations and multiple signs that became metaphors. The leading representative, along with Man Ray, of international modernity in Paris, he worked for the press, initiating photo-reportage; he took part in several important exhibitions, including “Film und Foto” in Stuttgart in 1929. Kertész nevertheless insisted on retaining his independence, keeping artistic movements, in particular Surrealism, at arm’s length. Nourished by his emotions, surprises, and personal associations, his work, with its mirrored images, reflections, shadows, and doubles, established him as a leading exponent of avant-garde photography. But he nevertheless avoided conventional doctrines and styles. The Fork (1928), for example, a perfect application of the modernist creed that held sway at the time, reveals another distinguishing feature of Kertész’s work: his interest in shadows cast by objects or people. In The Hands of Paul Arma (1928) and the extraordinary Self-Portrait (1927), these play subtly on the alternation between absence and presence, doubling and disappearance.

André Kertész always sought to take advantage of innovations that would enable him to reconfigure reality through unusual images. He very quickly became interested in the optical distortions produced by waves (The Swimmer, 1917), or by the polished surfaces of such objects as silver balls or by car headlights. In 1930, when the magazine VU commissioned him to take a portrait of its new editor, Carlo Rim, Kertész took him to the funhouse at Luna Park to pose in front of the distorting mirrors. Then, in 1933, at the request of the editor of a girlie magazine, Le Sourire, he produced an extraordinary series of female nudes, known as Distortions. He used two models, who posed with two distorting mirrors that, depending on the vantage point chosen, produced grotesque elongations, monstrous protuberances, or the complete disintegration of the body. Following his move to the United States, Kertész hoped to make use of this technique by adapting it to advertising, but he was met with incomprehension (it was not until 1976 that a book devoted to the Distortions was published in American and French editions).

United States, 1936-1962: A Lost Cloud

The offer of a contract from the Keystone agency (which would be broken after one year) prompted Kertész’s to move to New York in October 1936. His reservations about fashion photography, the rejection of his photo essays that “talked too much” according to the editorial board of Life, and the incomprehension that greeted the Distortions series gradually plunged Kertész into depression. The war and the curtailment of the “foreign” photographer’s freedom merely added to his difficulties. In 1947, in order to have a regular income, Kertész was forced to accept a contract from the magazine House & Garden. In 1952, he moved into an apartment overlooking Washington Square, which prompted a change of direction in Kertész’s work. He now watched and witnessed what was taking place on the surrounding terraces and in the square. He used telephoto lenses and zooms to create whimsical series, such as the one featuring chimneys.

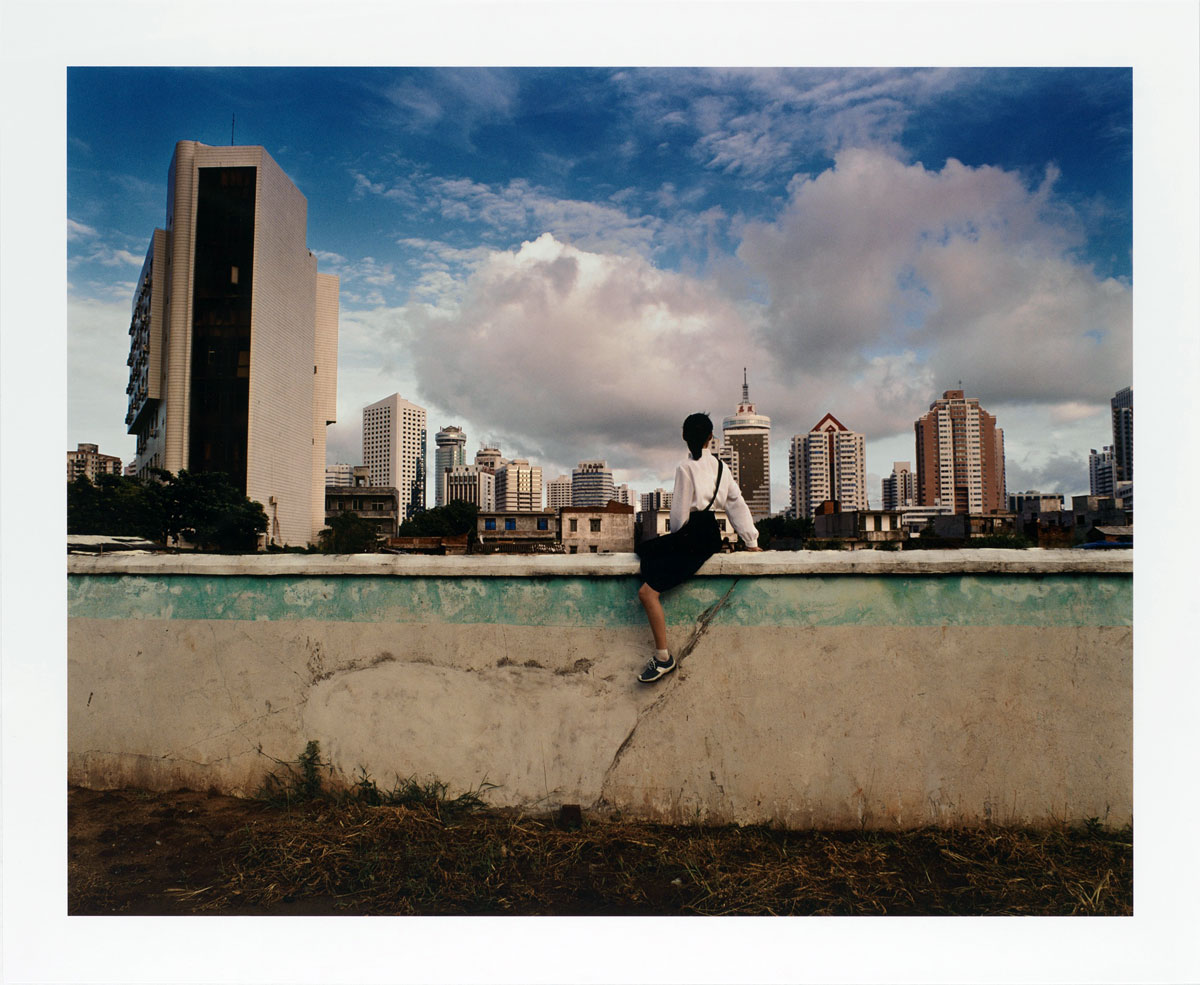

André Kertész lived in New York from 1936 to 1985 and he never stopped photographing “in” the city, rather than the city itself. He did not record the life of its neighbourhoods, the picturesque aspects of its various trades, and its often paradoxical architectural environments. For him, New York was a sound box for his thoughts, which the city echoed back to him in the form of photographs. He sought everywhere an antidote to the city’s regularity, in the dilapidated brick walls and the inextricable tangle of shadows, beams, and external staircases, and it is sometimes impossible to recognise specific places in these broken geometries: Kertész’s New York is highly fragmented, but a single photo could reveal the imaginary city.

He remained true to his intuitive, allusive personal style, and used his work to give voice to the sadness that undoubtedly permeated his entire life in New York, rendered most explicitly in The Lost Cloud (1937). Right up until the end of his life, he sought images of solitude, sometimes incorporating pigeons into them. On January 1, 1972, during a trip to Martinique, he caught the fleeting, pensive profile of a man behind a pane of frosted glass: this nebulous vision of a solitary man before the immensity of the sea was the last image in his retrospective collection, Sixty Years of Photography, 1912-1972, providing a very provisional conclusion to his career.

Returns and Renewal, 1963-1985

After his retirement in 1961, Kertész developed a new appetite for life and photography. Following a request from the magazine Camera for a portfolio, he made a sort of inventory of his available work. In 1963 he had one-man exhibitions at the Venice Photography Biennale and the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris, the latter enabling him to stay in a city that, on an emotional level, he had never left. In addition, he located and took possession of several boxes of negatives that had been entrusted to a friend in 1936, at the time of his departure, which prompted a review of his entire oeuvre and led to new prints, with fresh croppings. These various episodes, which can be seen as part of a general reassessment of the value of photography and its history, had a rejuvenating effect on Kertész (who was seventy at the time). The traveling exhibition “The Concerned Photographer” even presented him as a pioneer of photojournalism.

Kertész continued his never-ending search for images, both in the cities that he visited and from the window of his apartment. His two books J’aime Paris (1974) and Of New York … (1976) express his sense of being torn between two cultures. The death of his wife Elizabeth in 1977, shortly before his one-man show at the Centre Georges Pompidou, led him to develop an interest in Polaroids, which enabled him to adopt a more introspective approach. As always, emotion was the driving force behind his work. Of the fifty-three Polaroids brought together in the small book From My Window, dedicated to Elizabeth, Kertész, always curious about new technology, was in reality capturing the light of his recollections and the distortions of his memory.”

Michel Frizot and Annie-Laure Wanaverbecq, curators of the exhibition

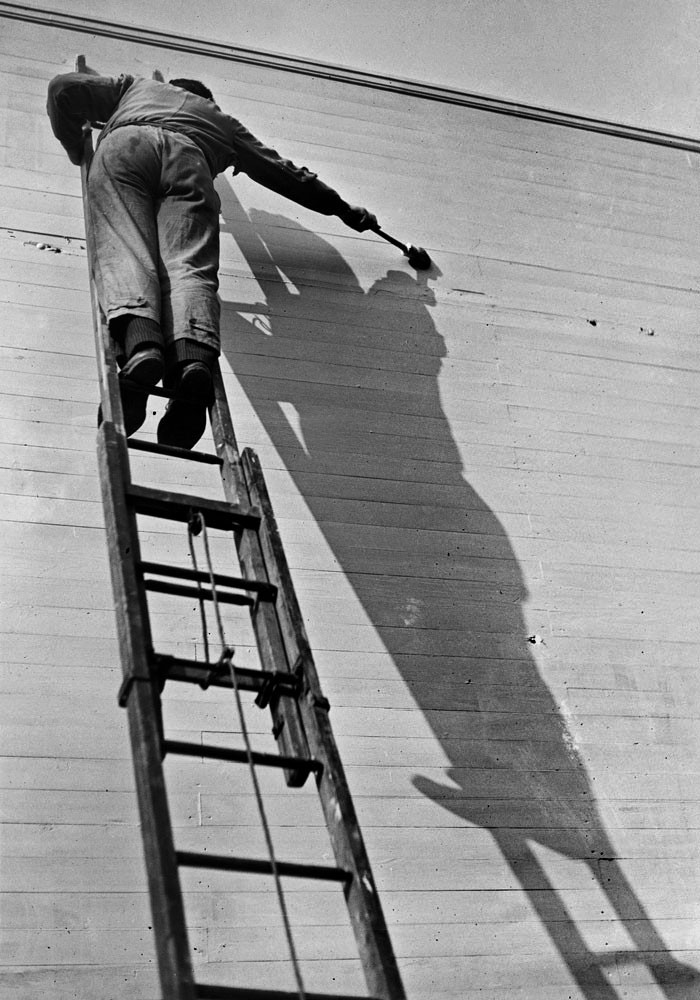

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Peintre d’ombre, Paris (Shadow painter, Paris)

1926

Gelatin silver print

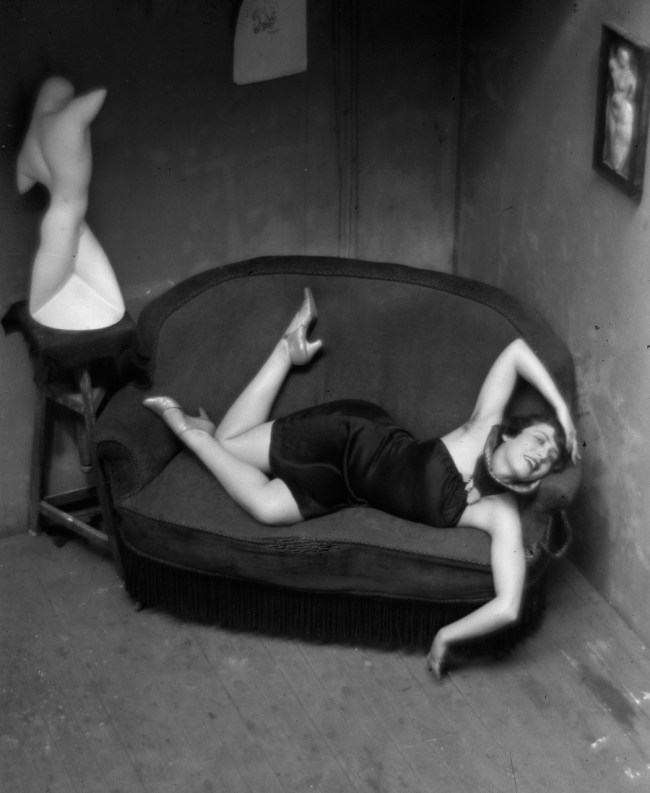

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Satiric Dancer

1926, printed in the 1950s

Gelatin silver print

Bibliothèque nationale de France

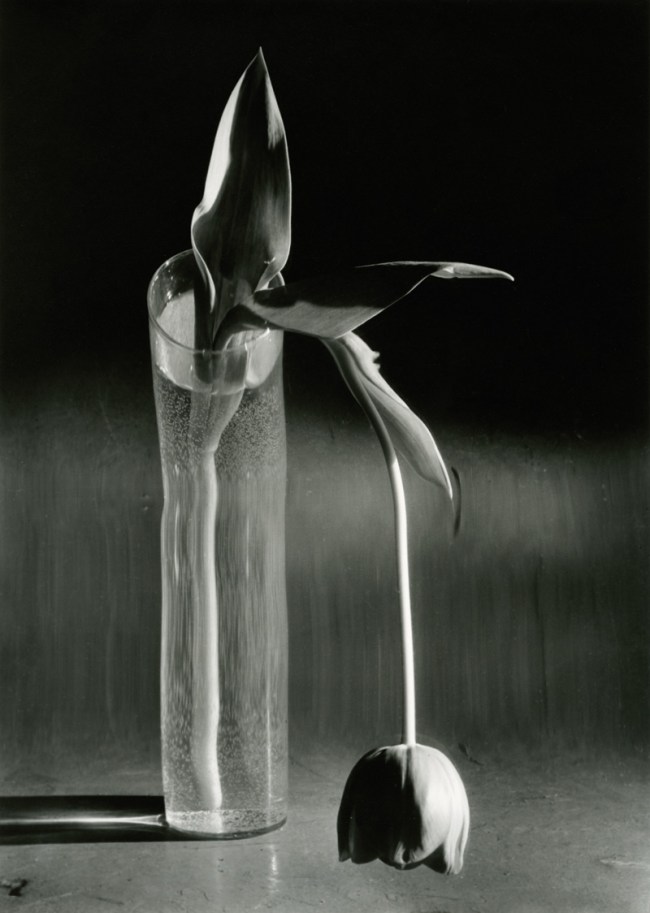

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Melancholic Tulip

New York, 1939, printed c. 1980

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy Bruce Silverstein Gallery

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Lost Cloud, New York

1937, printed in the 1970s

Gelatin silver print

Courtesy Sarah Morthland Gallery, New York

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

Washington Square, New York

1954

Gelatin silver print

André Kertész (Hungarian, 1894-1985)

July 3, 1979

Polaroid

Jeu de Paume

1, place de la Concorde

75008 Paris

métro Concorde

information: 01 47 03 12 50

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 12 – 8pm

Saturday and Sunday 11am – 7pm

Closed Monday (including public holidays)

![Felix Gonzalez-Torres (American born Cuba, 1957–1996) '[No Title]' 1985 from the exhibition 'Between Here and There: Passages in Contemporary Photography' at The Metropolitan Museum of Art Felix Gonzalez-Torres (American born Cuba, 1957–1996) '[No Title]' 1985 from the exhibition 'Between Here and There: Passages in Contemporary Photography' at The Metropolitan Museum of Art](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/felix-gonzalez-torres-no-title-1985.jpg?w=284)

You must be logged in to post a comment.