Exhibition dates: 6th October, 2011 – 8th January, 2012

Curators: Nicholas Serota and Mark Godfrey

Many thankx to the Tate Modern for allowing me to publish the artwork in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Reader

1994

Courtesy San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

© Gerhard Richter

“Curated by Nicholas Serota and Mark Godfrey, this show sets up all sorts of telling juxtapositions, while following the thread not just of Richter’s thinking, but of history – and in particular German history – since the second world war. We go from the saturation bombing of Dresden and Cologne to 1960s West German consumerism, from 1970s domestic terrorism to 9/11. There are paintings devoted to Richter’s parents, his aunts and uncles, and what happened to them in wartime. There are paintings devoted to his children, and to becoming a father again in his 60s. He confronts the personal with the public, one kind of history with another. …

Caspar David Friedrich’s German Romanticism, Titian’s Venetian colour, constructivism and postwar gestural painting, minimalism and process art are all grist to Richter’s mill. His 1973 Annunciation After Titian is a reworking from a postcard of the original, while the impossibility of Friedrich’s Romanticism returns time and again in Richter’s seascapes and his Greenland photographs. “I was always looking,” he once said, “for a third way, in which eastern realism and western modernism would be resolved into one redeeming construct.” If this remains Richter’s programme, it is one riven with the irreconcilable, a friction on which his art depends.”

Adrian Searle. “Tenderness and terror: the Tate’s Gerhard Richter retrospective,” on The Guardian website Tuesday 4th October 2011 [Online] Cited 03/11/2024

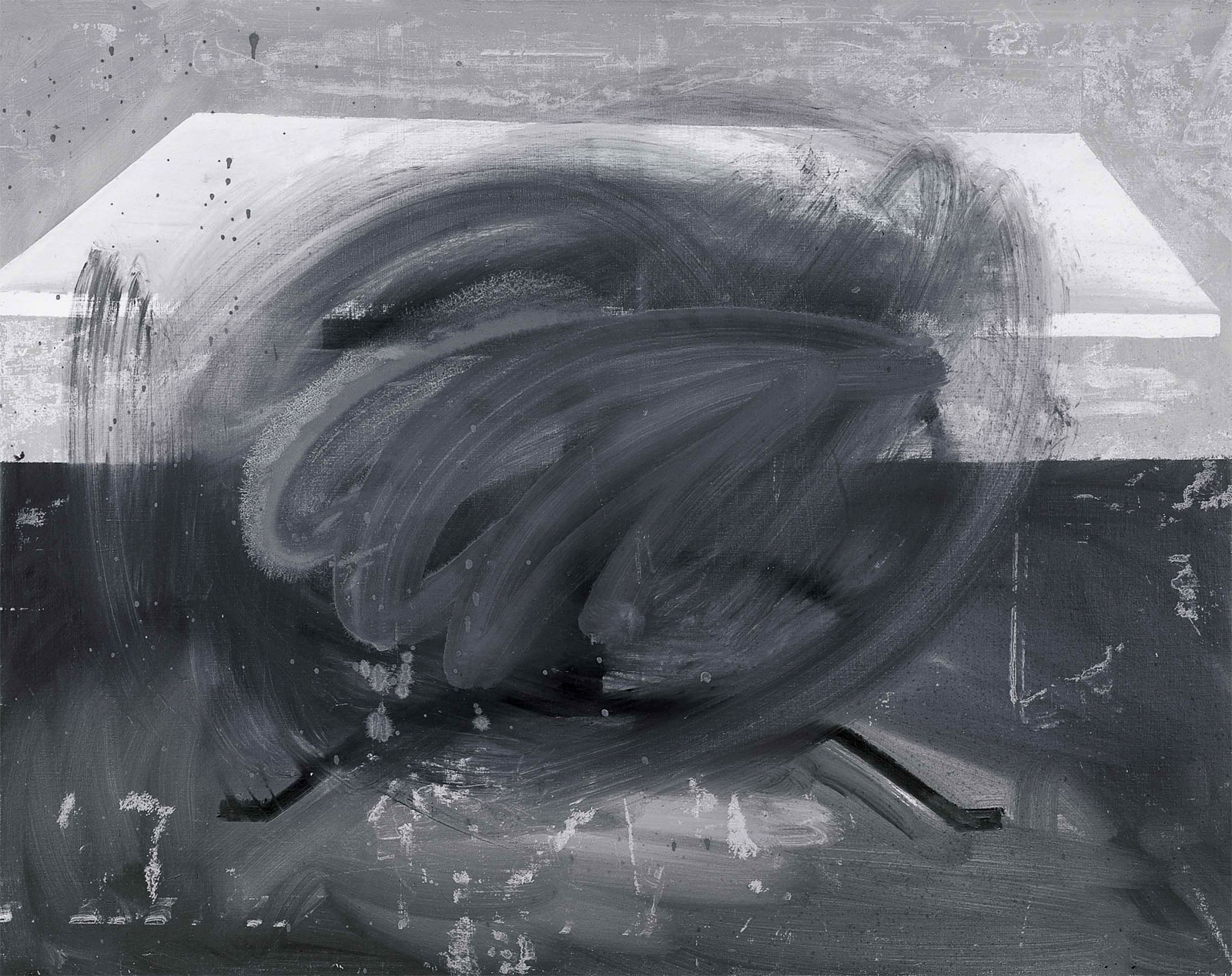

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Table (Tisch)

1962

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Mustang Squadron

1964

Private Collection

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Tante Marianne (Aunt Marianne)

1965

Private Collection

© Gerhard Richter

Wedded to this aesthetic of indifference, it seems more than coincidental that he introduced into his practice subject matter directly related to Germany’s recent Nazi past, images from his family album (one of the few possessions he brought over from the East) that most artists would have chosen to keep concealed. Uncle Rudi for instance is a full sizes portrait of his uncle in the uniform of the Wehrmacht – a going away photo, it turns out, as he was to die some months later. What distinguishes this portrait and many others is the addition of Richter’s signature blur. Paint has been dragged across the wet surface with a dry brush, signalling a whole variety of responses. Often interpreted as replicating an out of focus snapshot, evoking speed, or signalling a temporal distancing by underlining the difference between the ‘now’ of the viewer and the ‘then’ of whatever was captured in the photograph, this flurry of soft or hard brush strokes also signals a degree of moral and emotional ambiguity – despite the painter’s insistence on a lack of intentionality on his part. Take his portrait of Aunt Marianne that depicts his maternal aunt cradling Richter as a none-too-happy baby. A schizophrenic, she was sterilized and eventually starved to death by the Nazis. The blur of the brushstrokes bring her and the baby together suggesting the very emotional attachment that Richter was initially keen to disavow. During an interview in 1986 Richter confessed that this dispassionate stance of indifference was mere subterfuge and pretence on his part: “Content definitely – though I may have denied this at one time, by saying that it had nothing to do with content, because it was supposed to be about copying a photograph and giving a demonstration of indifference.”

Anna Leung. “Gerhard Richter: Panorama at Tate Modern,” on The Arts Section website Nd [Online] Cited 05/12/2024

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Uncle Rudy

1965

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Seascape (Sea-Sea)

1970

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Betty

1977

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Candle

1982

Museum Frieder Burda, Baden-Baden, Germany

© Gerhard Richter

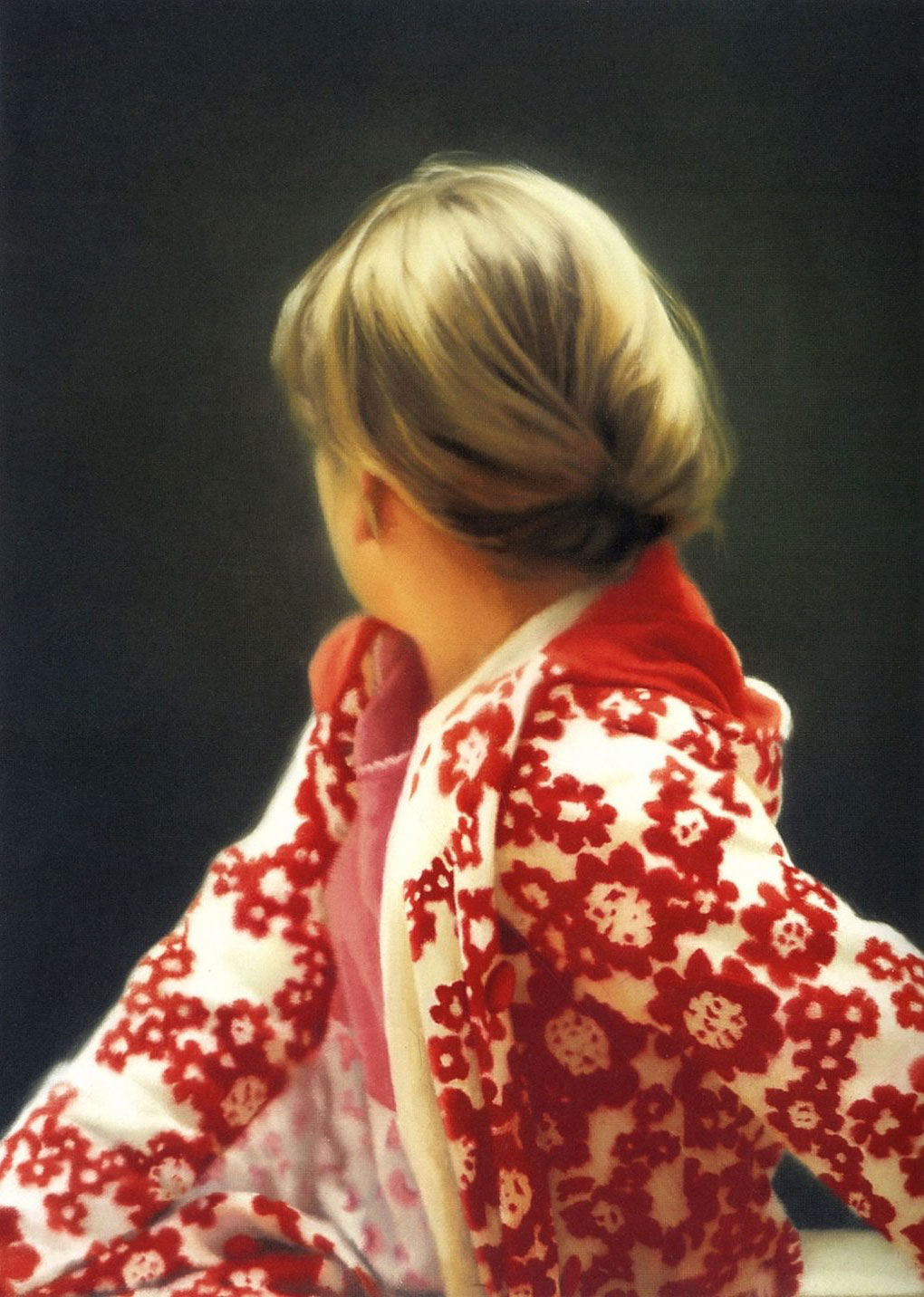

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Betty

1988

Saint Louis Art Museum, USA

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter’s extremely productive career needs to be seen against this shift in attitudes and expectations when pictorial references were no longer drawn directly from the natural world but from an ever-growing nexus of information. Empirical data was being rapidly replaced by conceptual data. From 1961 when he settled in West Germany Richter alternated between figuration and non-figuration treating a wide range of subjects and employing a wide variety of means while not valuing one practice over another. As we shall see Richter is equally adept at dealing with historical genres such as the nude, landscape, portraits and history painting as he is in investigating colour and its absence in his monochromes and colour charts and in his densely layered, explosively coloured abstract canvases. For Richter, Abstraction is as real as Realism is abstract, for what fascinates him is not the image per se or its absence but appearance or semblance as our apprehension of appearance. Richter readily admits that it is inevitable that figurative elements be seen in abstraction and denies any difference between what for him is a false polarity. That this panoply of styles remains Richter’s consistent trademark throughout his long career can be seen as we wander through the rooms of this vast exhibition. Each room displays figurative paintings, mostly from photographic imagery, side by side with abstract paintings. There are two exceptions; the first is the room devoted to 18 October 1977, a cycle of fifteen photo-paintings based on the deaths of the Baader-Meinhof terrorists in Stammheim high security prison, the second the Cage room of abstract paintings that brings the exhibition to an close. Throughout the exhibition we see Richter appropriating mutually contradictory trends associated with Hyperrealism, Minimalism and Conceptual Art while at the same time honing his craft as a painter to produce some extraordinarily beautiful images. Impossible to categorise he demonstrates his determination to confront the crisis of representation on one hand and that of Germany’s recent history on the other.

Anna Leung. “Gerhard Richter: Panorama at Tate Modern,” on The Arts Section website Nd [Online] Cited 05/12/2024

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Abstract Painting (726)

1990

Tate

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Abstract Painting

1990

Tate. Purchased 1992

© Gerhard Richter

Photo: Lucy Dawkins

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Forest (3) and Forest (4)

1990

Private collection (left) and The Fisher Collection, San Francisco (right)

© Gerhard Richter

Photo: Lucy Dawkins

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Forest (3)

1990

Private collection

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter is widely regarded as one of the most important artists working today. Spanning nearly five decades, and coinciding with the artist’s eightieth birthday, Gerhard Richter: Panorama is a major retrospective that groups together significant moments of his remarkable career.

As evoked by the title Panorama this exhibition presents a broad look at the wide range of Richter’s practice, discovering contradictions and connections, continuities and breaks. Each room is devoted to a particular moment of his career showing how he explored a set of ideas. While the focus is on painting, the exhibition includes glass constructions, mirrors, drawings, and photographs, and explores how Richter uses these media to ask questions about painting.

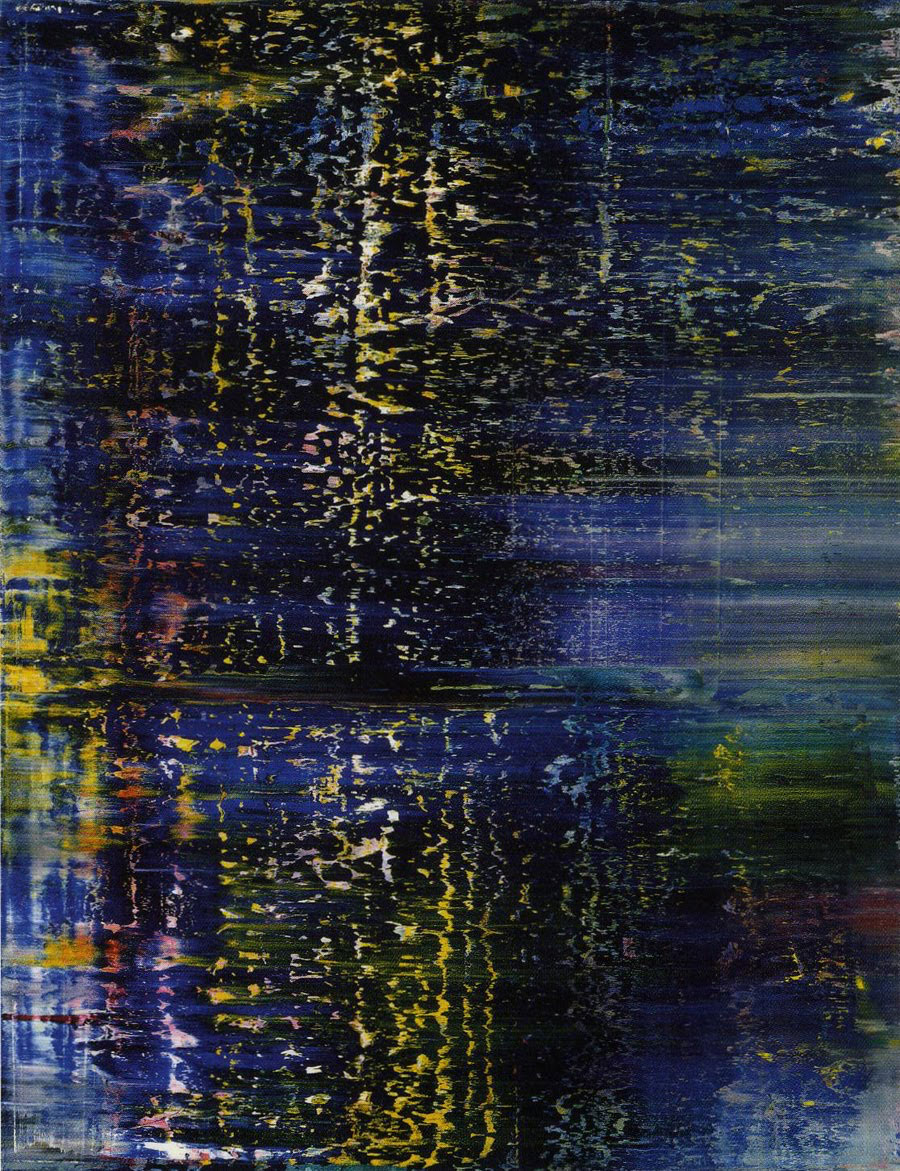

The exhibition includes many of Richter’s most well-known works such as Ema (Nude descending a staircase) 1966, Candle 1982, Betty 1988 and Reader 1994. There are also important works that are rarely shown: the first Colour Chart from 1966, 4 Panes of Glass 1967, a triptych of Cloud paintings from 1970, and, for the first time outside Germany, Richter’s monumental twenty metre long painting Stroke (on Red) 1980, based on a photograph of a brush stroke. There are several groups of important abstract paintings including a room of brightly coloured works from the early 1980s, a room of monumental squeegee paintings from the 1990s, and the Cage series 2006.

Richter was one of the first German artists to reflect on the history of National Socialism, creating paintings of family members who had been members, as well as victims of, the Nazi party. In the late 1980s, looking back to the history of radical political activity in West Germany in the 1970s, he produced the fifteen-part work 18 October 1977 1988, a sequence of black and white paintings based on images of the Baader Meinhof group. At the same time as developing a complex body of abstract work, often using squeegees to drag paint across the surface of his canvases, Richter has continued to respond to significant moments in history. In 2005 he painted September, an image of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in New York in 2001, which is shown for the first time in the UK in this exhibition.

Richter is often celebrated for the diversity of his approaches to painting. His practice can seem to be structured by various oppositions, with paintings after photographs as well as abstract pictures; traditional still-lifes alongside highly charged subjects; monochrome grey works and multicoloured grids. Some paintings are planned out and ordered; others are the result of unpredictable accumulations of marks and erasures. Richter sometimes maintains these oppositions, but at other times he undoes them. This exhibition shows how he often brings abstraction and figuration together, and explores related ideas in very different looking works. The exhibition reveals breaks and new beginnings in his career, but it also reveals questions that he has asked throughout his life.

Short Biography

Richter was born in Dresden in 1932 and after training in the East, moved to West Germany in 1961. He was part of a group of painters working in Düsseldorf, that included Sigmar Polke and Konrad Lueg, who turned to image-based painting during the emergence of American Pop art. Major solo exhibitions include the 36th Venice Biennale in 1972, his first large-scale retrospective at Städtische Kunsthalle und Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf in 1986 and Forty Years of Painting, a large-scale retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2002. He installed Black Red Gold in the foyer of the Reichstag building in Berlin in 1999 and the window that he designed for Cologne Cathedral was completed in 2007. Richter lives and works in Cologne.”

Press release from the Tate Modern website

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Panels from 18 October 1977

1988

© Gerhard Richter

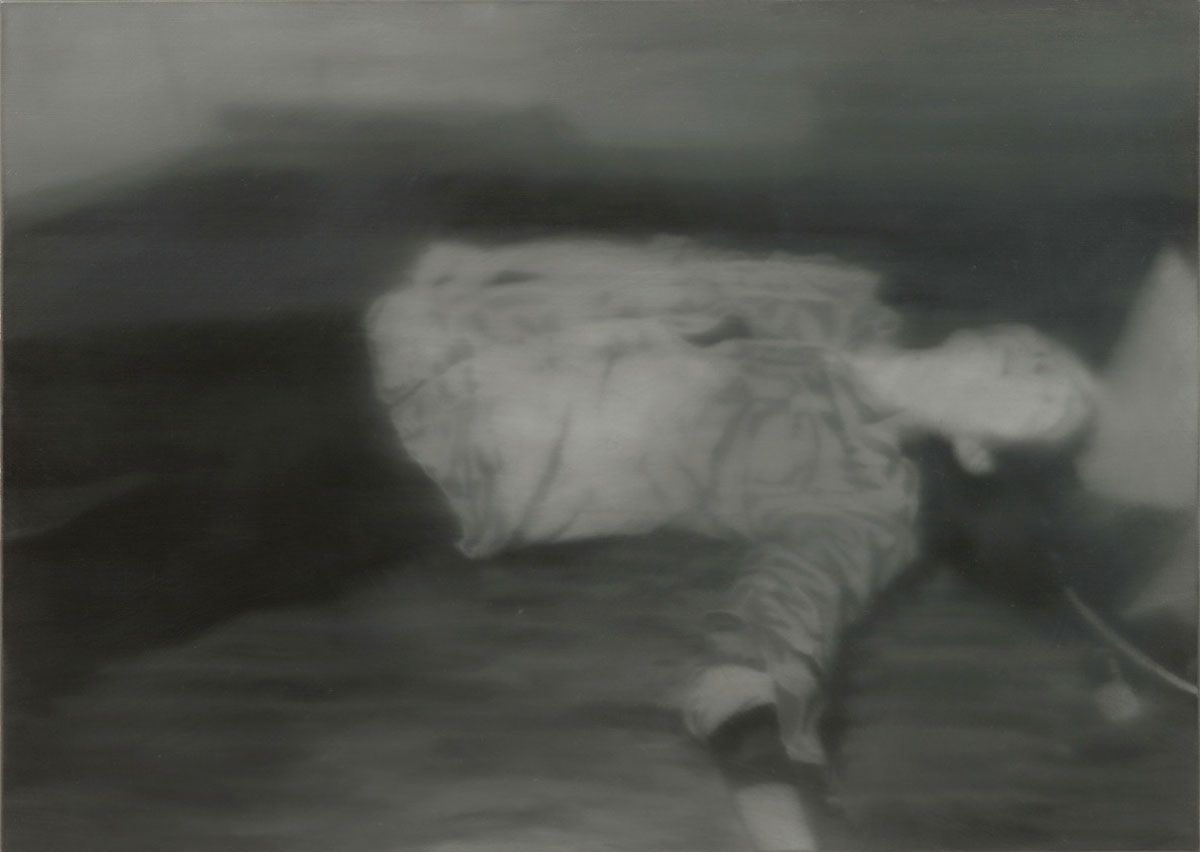

Gerhard Richter debuted his 15-painting suite 18 October 1977, concerning the radical left-wing Baader-Meinhof Group that had shaken Germany with a two-year campaign of terror, with more public ceremony than usual. At a press conference at the Museum Haus Esters in Krefeld, introducing the pictures before they were first shown in early 1989, he offered a curious speech, reflecting that, “I hope…there is purpose in looking at those deaths, because there is something about them that should be understood.” If Richter’s words recognized the particularly ambitious nature of these paintings among his growing body of work, it also gave listeners little guidance as to what it was that should be understood. …

Soon after, Richter began wiping across the still-wet surface of his photo-paintings with a squeegee to soften the edges and blur the image. This signature blur can evoke a range of things – the motion of the viewer or the camera, the passage of time, but also something more metaphoric, of the type suggested in the artist’s 1971 musing: “My relationship to reality has a great deal to do with imprecision, uncertainty, transience, incompleteness.” At times, Richter also suggested that this fuzzy gaze might serve a role in helping to focus the mind: “You do not see less,” he wrote, “by looking at a field out of focus through a magnifying glass.” In the October cycle, Richter seems to amp his blurring technique up a notch, so that the images are more obscured, more diffuse than usual, in some cases approaching the edge of recognisability.

The date of the title – October 18, 1977 – marks the bloody denouement of a story that had played out over several years in front of a shaken German nation. From 1968 to 1977, the Baader-Meinhof Group led a campaign of shootings and kidnappings aimed at undermining the German state, leaving more than 30 people dead. The group’s founders – Holger Meins, Ulrike Meinhof, Gudrun Ensslin, and Andreas Baader – and several other members of the group were arrested and held in Stammheim prison. On October 17, a plane was diverted to Mogadishu by hijackers who demanded the release of the members of the group from prison. Early the next morning, following the successful liberation of the plane by the German military, three of the Baader-Meinhof Group were found dead in their cells from apparent suicide – though the proximity of these events prompted speculation about their cause of death. …

Richter acknowledged how profoundly unsettling he found the events around the Baader-Meinhof Group: “The deaths of the terrorists, and the related events both before and after,” he reflected, “stand for a horror that distressed me and has haunted me as unfinished business ever since, despite all my effort to repress it.” Perhaps as a way of processing things, Richter began to collect materials related to the group, holding onto “a number” for years before he began painting the October cycle, filed “under the heading of unfinished business.” In fact, over 100 images related to the Baader-Meinhof Group appear in Atlas, Richter’s ongoing scrapbook-like compendium of photographic source material.

When he began working in earnest on what would become 18 October 1977, Richter drew some of his source images from newspapers and magazines or snapshots of television coverage – markers of the pervasiveness of media coverage of the Baader-Meinhof Group during their violent reign and in its aftermath. But others, taken from police evidentiary photographs, were far less readily available, and serve as tokens of Richter’s preoccupation with the topic and his determined research efforts in preparation for painting. …

The narrative arc Richter creates begins in a banally sweet portrait image of a young woman and ends in a collective ritual of public mourning. Yet both, Richter seems to suggest, are inadequate to our understanding of what has taken place. What truth, he seems to ask, do photographs offer? Can violence or righteousness be discerned in the blur of grays?

But he declined to offer answers: “It is impossible for me to interpret the pictures,” he concluded in notes made for the work’s unveiling. “In the first place they are too emotional; they are, if possible, an expression of speechless emotion. They are the almost forlorn attempt to give shape to feelings of compassion, grief, horror (as if the pictorial repetition of events were a way of understanding these events, being able to live with them).”

Leah Dickerman. “Gerhard Richter’s Enigmatic Cycle in The Long Run,” on the MoMA website March 1, 2019 [Online] Cited 05/12/2024

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Panels from 18 October 1977

1988

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Abstract Painting

1990

Private Collection

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Demo

1997

The Rachofsky Collection

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Cage 4

2006

Tate. Lent from a private collection 2007

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

Ema (nude descending a staircase)

1992

© Gerhard Richter

Gerhard Richter (German, b. 1932)

14. Feb. 45

2002

Tate

© Gerhard Richter

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 6pm

Back to tophttps://artblart.com/2012/01/06/exhibition-gerhard-richter-panorama-at-tate-modern-london/

You must be logged in to post a comment.