Exhibition dates: 7th October, 2015 – 10th January, 2016

Curator: Dr Xavier Bray

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Duke of Wellington

1812-1814

Oil on mahogany

64.3 x 52.4cm

© The National Gallery, London

Rushing through a dimly lit gallery I remember stumbling upon my first, larger than life, full length Goya portrait in the Louvre, a portrait of a women in a pale blue dress. It literally stopped me in my tracks, the visceral affect was so powerful. There was a certain tactility to the painting, a presence to the figure that produced this emotive response. And the light that emanated from the painting. I think my jaw dropped to the floor.

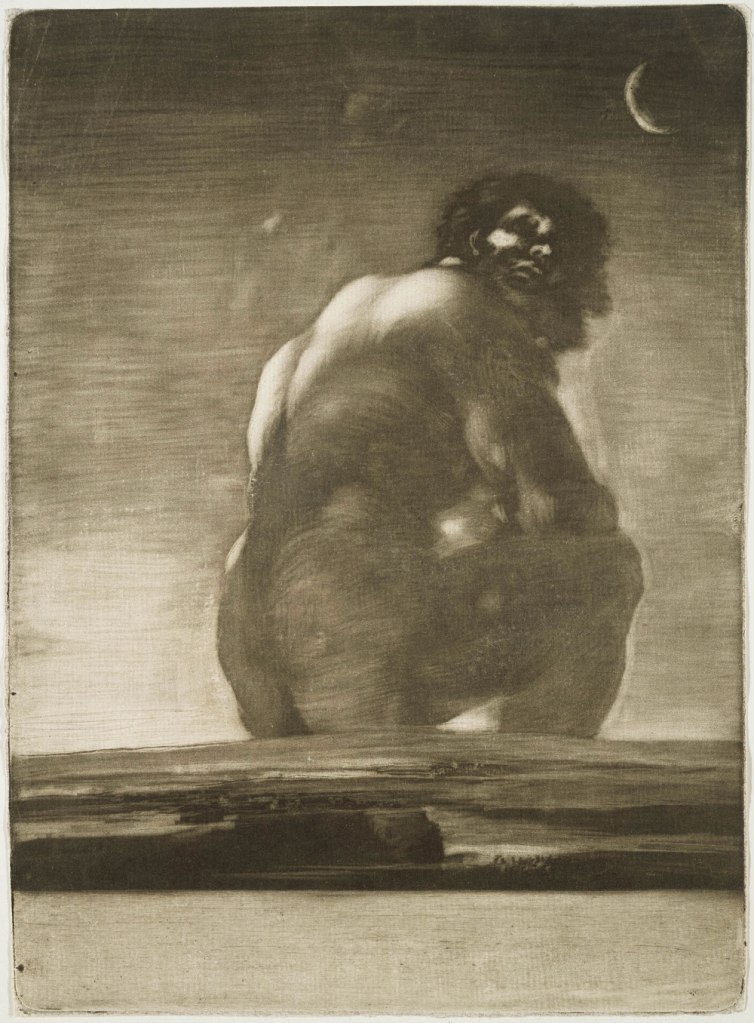

Goya can be cutting when he wants to be, as in the pompous portrait of the buffoon Ferdinand VII in Court Dress (1814-1815, below); he can be precise and reserved as in Don Valentín Bellvís de Moncada y Pizarro (around 1795, below) where the eyes are the key to the portrait; he can be strong and forthright as in the muscular portrait of Martín Zapater (1797, below); or he can be inscrutably honest Self Portrait before an Easel (1792-1795, below) and loving Mariano Goya y Goicoechea (the artist’s grandson) (1827, below). But above all, he is human.

The richness and combination of colours, the sense of space that surrounds the sitter (with their mainly contextless backgrounds and the isolation of the figure in pictorial space), their power – both personal and political – and the certain wariness, weariness and insouciance of their expressions… are just a marvel to behold. It’s as though the sitters had just stopped for a moment to ponder their lives. Almost as though they had conjured or envisaged their own visage, as if from a dream.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery, London for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Count of Altamira

1787

Oil on canvas

177 x 108cm

Colección Banco de España

© Colección Banco de España

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Countess of Altamira and Her Daughter, María Agustina

1787-1788

Oil on canvas

195 x 115cm

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga

1788

Oil on canvas

127 x 101.6cm

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Jules Bache Collection, 1949

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Countess-Duchess of Benavente

1785

Oil on canvas

105 × 78cm

Private Collection, Spain

© Joaquín Cortés

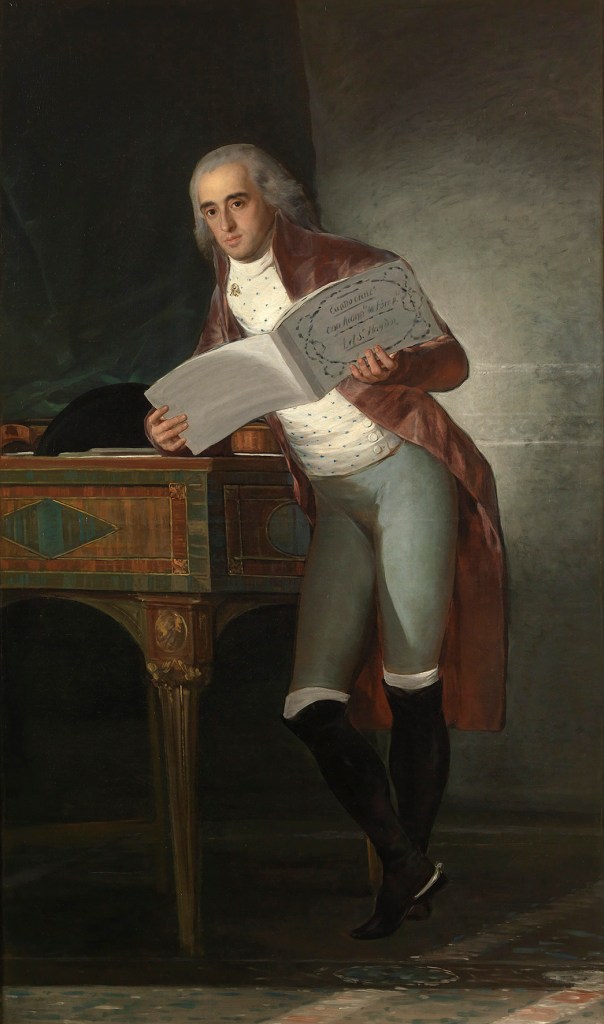

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Duke of Osuna

1797-1799

Oil on canvas

113 x 83.2cm

The Frick Collection, New York, Purchase, 1943

© The Frick Collection

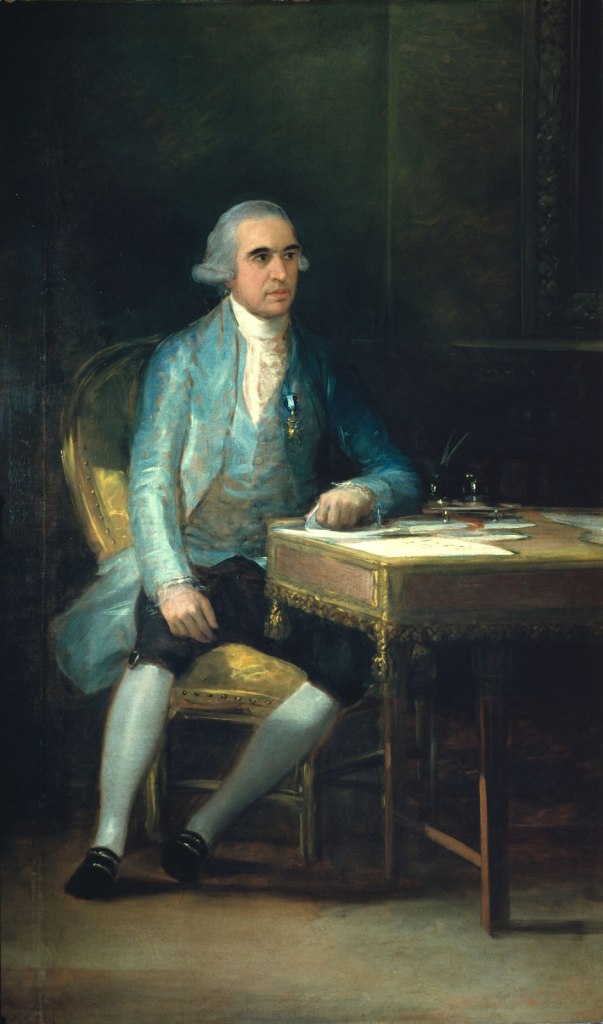

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Portrait of the Count of Floridablanca

1783

Oil on canvas

262cm (103.1 in). Width: 166cm (65.4 in).

Colección del Banco de España, Madrid

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Duke and Duchess of Osuna and their Children

1788

Oil on canvas

225 x 174cm

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

© Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Marquis of Villafranca and Duke of Alba

1795

Oil on canvas

195 x 126cm

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

© Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Duchess of Alba

1797

Oil on canvas

210.1 × 149.2cm

On loan from The Hispanic Society of America, New York, NY

© Courtesy of The Hispanic Society of America, New York

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828) is one of Spain’s most celebrated artists. He was an incisive social commentator, considered (even during his own lifetime) as a supremely gifted painter who took the genre of portraiture to new heights. Goya saw beyond the appearances of those who sat before him, subtly revealing their character and psychology within his portraits.

Born before Mozart and Casanova, and surviving Napoleon, Goya’s life spanned more than 80 years during which he witnessed a series of dramatic events that changed the course of European history. Goya: The Portraits will trace the artist’s career, from his early beginnings at the court in Madrid to his appointment as First Court Painter to Charles IV, and as favourite portraitist of the Spanish aristocracy. It will explore the difficult period under Joseph Bonaparte’s rule and the accession to the throne of Ferdinand VII, before concluding with his final years of self-imposed exile in France. Exhibition curator Dr Xavier Bray says:

“The aim of this exhibition is to reappraise Goya’s status as one of the greatest portrait painters in art history. His innovative and unconventional approach took the art of portraiture to new heights through his ability to reveal the inner life of his sitters, even in his grandest and most memorable formal portraits.”

This landmark exhibition will bring to Trafalgar Square more than 60 of Goya’s most outstanding portraits from both public and private collections around the world. These include works that are rarely lent, and some which have never been exhibited publicly before, having remained in possession of the descendants of the sitters. The exhibition will show the variety of media Goya used for his portraits; from life-size paintings on canvas, to the miniatures on copper and his fine black and red chalk drawings. Organised chronologically and thematically, we will for the first time be able to engage with Goya’s technical, stylistic, and psychological development as a portraitist.

From São Paulo to New York, and Mexico to Stockholm, private and institutional lenders have been outstandingly generous, including 10 exceptional loans from the Museo del Prado, Madrid. One of the stars of the show will undoubtedly be the iconic Duchess of Alba (The Hispanic Society of America Museum & Library) which has only once left the United States and has never travelled to Britain. Painted in 1797, this portrait of Goya’s close friend and patron shows the Duchess dressed as a ‘maja’, in a black costume and ‘mantilla’ pointing imperiously at the ground where the words ‘Solo Goya’ (‘Only Goya’) are inscribed.

Other patrons who assisted Goya on his upward trajectory to become First Court Painter, as Velázquez had done more than 150 years before him, are well represented: these include The Count of Floridablanca (Banco de España, Madrid) and The Duke and Duchess of Osuna and their Children (Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid) – both key and influential patrons. The immense group portrait of The Family of the Infante Don Luis de Borbón (Magnani-Rocca Foundation, Parma), will be reunited with some of the other portraits Goya painted of the Infante’s young family who were living in exile from the Spanish court.

Other highlights will include the charismatic portrait of Don Valentin Bellvís de Moncada y Pizarro (Fondo Cultural Villar Mir, Madrid) which is unpublished and has never been seen before in public, and the rarely exhibited Countess-Duchess Benavente (Private Collection, Spain). The recently conserved 1798 portrait of Government official Francisco de Saavedra (Courtauld Gallery, London) will be exhibited for the first time in more than 50 years alongside its pendant painted in the same year, showing his friend and colleague Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (Museo del Prado, Madrid).

The Countess of Altamira and her daughter, María Agustina, which has never been lent internationally from the Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, will come to Europe for the very first time to be reunited with her husband The Count of Altamira (Banco de España, Madrid) and their son Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), wearing a fashionably expensive red costume and playing with a pet magpie (which holds the painter’s calling card in its beak). It was shortly after completing his imposing portrait of the Countess, wearing a shimmering embroidered silk gown and shown with an introspective expression, that Goya was appointed court painter to Charles IV, King of Spain.

It was in his royal portraits in particular that Goya managed to combine his insightful observation and technical refinement to create unique, memorable portraits; in these he condensed the various aspects of his sitter’s personality into a subtle look or gesture, which often did not flatter his sitters. Charles III in Hunting Dress (Duquesa del Arco) stands in a pose directly inspired by Velázquez’s hunting portraits of the Spanish royal family in the previous century, but the candid portrayal of a weather-beaten face with its marked wrinkles and a somewhat ironic gesture is unique to Goya, clearly revealing to us the personality of the King – an enlightened man, a lover of nature and his people, who wished to be approached as ‘Charles before King’. Similarly, in the portrait of Ferdinand VII (Museo del Prado, Madrid) we can imagine Goya’s mistrust of the pompous and selfish monarch who abolished the constitution and reintroduced the Spanish Inquisition.

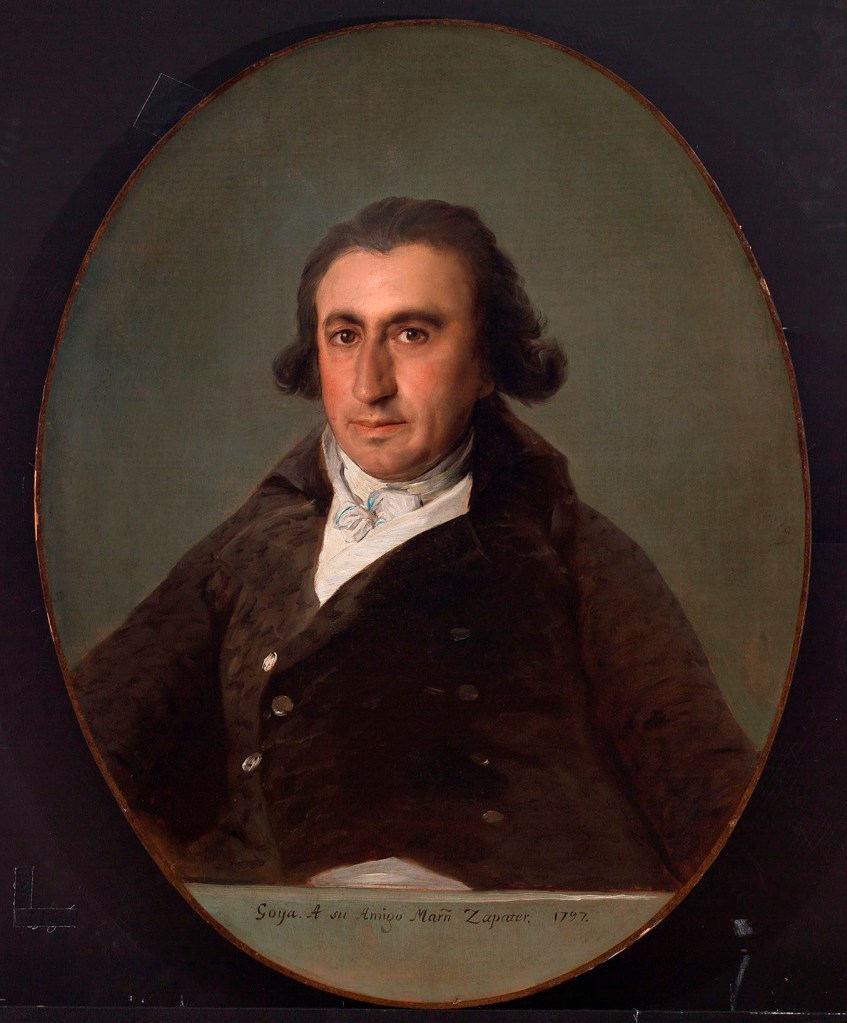

In contrast to the formality of his royal portraits, the exhibition also features more personal works by Goya, including a number of self-portraits in different media, and depictions of his friends and family. 47 years lie between the first Self Portrait (about 1773, Museo Goya, Colección Ibercaja, Zaragoza) in the show, completed when Goya was in his late 20s, and the last, the poignant Self Portrait with Doctor Arrieta (1820, The Minneapolis Institute of Art) painted after an illness from which he almost died when he was 74 years old. There will also be a chance to ‘meet’ the people who were closest to Goya; his wife Josefa Bayeu (Abelló Collection, Madrid), his son Javier Goya (Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Private Collection; Museo de Bellas Artes, Zaragoza) and his best friend and life-long correspondent Martin Zapater (Bilboko Art Eder Museoa / Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao). The exhibition also includes the last work Goya ever painted, of his only, beloved grandson Mariano Goya (Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas) – painted just months before Goya’s death on 16 April, 1828, this portrait is a testament to the genius, skill, and unfaltering creativity of an artist who persevered with his craft to his very last days.

Press release from the National Gallery website

Installation photographs of the exhibition Goya: The Portraits at the National Gallery, London

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

The Marchioness of Santa Cruz

1805

Oil on canvas

124.7 × 207.7cm

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

© Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Self Portrait before an Easel

1792-1795

Oil on canvas

42 x 28cm

Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid

© Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, Madrid

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Self Portrait after Illness of 1792-1793

1795-1797

Brush and grey wash on laid paper

15.3 x 9.1cm

Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1935

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Self Portrait

1815

Oil on canvas

45.8 × 35.6cm

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

© Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Self Portrait with Doctor Arrieta

1820

Oil on canvas

114.6 × 76.5cm

Lent by The Minneapolis Institute of Art, The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund

© Minneapolis Institute of Art

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos

1798

Oil on canvas

205 x 133cm

Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

© Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Portrait of Don Francisco de Saavedra

1798

The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London

The Spanish politician Francisco de Saavedra was noted for his integrity. In late 1798 Saavedra and his great friend and ally, Gaspar de Jovellanos, were appointed to the two highest political offices in Spain: Minister of Finance and Minister of State. Jovellanos was one of Goya’s most consistent supporters, and the two men commissioned a pair of portraits from him.

The two pictures are closely related. In each, the sitter faces to the right, and sits on a round-backed chair beside a table. But while Jovellanos is thoughtful, Saavedra seems about to leave his paper-strewn desk having decided on a course of action. The simplicity of the background may be influenced by Goya’s knowledge of eighteenth-century English portraiture. It could, however, have been chosen by Saavedra, who was known for the well ordered and ‘English’ character of his household.

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Charles IV in Hunting Dress

1799

Oil on canvas

205 x 129cm

Colecciones Reales, Patrimonio Nacional, Palacio Real de Madrid

© Patrimonio Nacional

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

María Luisa wearing a Mantilla

1799

Oil on canvas

205 x 130cm

Colecciones Reales, Patrimonio Nacional, Palacio Real de Madrid

© Patrimonio Nacional

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Mariano Goya y Goicoechea (the artist’s grandson)

1827

Oil on canvas

52.1 x 41.3cm

Meadows Museum, SMU, Dallas. Museum Purchase with Funds Donated by the Meadows Foundation and a Gift from Mrs Eugene McDermott, in honour of the Meadows Museum’s 50th Anniversary

© Photograph by Michael Bodycomb

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Doña Isabel de Porcel

before 1805

Oil on canvas

82 x 54.6cm

The National Gallery, London, bought, 1896

© The National Gallery, London

The exhibition Goya: The Portraits includes around 70 works unquestionably by his hand, provides us with a unique opportunity to look more closely at Portrait of Doña Isabel de Porcel and ask the question: is she really by Goya? This Room 1 display will present historical information surrounding the portrait and its acquisition by the National Gallery in 1896, together with technical evidence, including an X-ray image which reveals an earlier portrait painted underneath.

Who was Doña Isabel de Porcel?

The sitter has long been identified as Doña Isabel Lobo de Porcel on account of an inscription on the back of the original canvas. Goya exhibited a portrait of Doña Isabel Lobo de Porcel in Madrid in 1805, and this has traditionally been linked to the National Gallery painting. Isabel married Antonio Porcel (Secretary of State for Spain’s American Colonies) in 1802 and the couple had four children. Isabel died in 1842, surviving her husband by 10 years. Antonio, who was a political associate of Goya’s friend and patron Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (whose portrait can be seen in Goya: The Portraits), was also painted by Goya in 1806, but his portrait was destroyed by fire in 1953.

The National Gallery’s purchase of Portrait of Doña Isabel de Porcel

The National Gallery bought Portrait of Doña Isabel de Porcel in June 1896 for just over £404. It was among the first pictures by the artist – and the very first portrait by Goya – to enter the National Gallery collection, having made its first Goya purchases (A Picnic and A Scene from ‘The Forcibly Bewitched’) the previous month. The portrait was no longer owned by the sitter’s descendants when the Gallery acquired it, having been sold by the Porcel y Zayas family from Granada, in whose possession it had apparently remained until around 1887, to Don Isidro de Urzáiz Garro (d. 1894). It was from the latter’s heir, Andrés de Urzáiz (1866-1912), that the Gallery acquired the portrait about 10 years later.

A question of attribution

The glamorous sitter is shown wearing a black lace ‘mantilla’, a traditional headdress which became fashionable among the Spanish aristocracy in the late 18th century. Although painted with tremendous flair, the picture’s brushwork – when compared with Goya’s other portraits – lacks his customary subtlety in describing transparencies and textures. Isabel is extremely charismatic but we struggle to grasp her psychological state – something in which Goya invariably excelled.

The hidden portrait

When an X-ray image was made of the Portrait of Doña Isabel de Porcel during conservation treatment in 1980, another portrait was unexpectedly found underneath. The head and striped jacket of the underlying figure are clearly visible in the X-ray, and Doña Isabel de Porcel was painted directly on top of the initial portrait, without first hiding it with new priming. Although perhaps surprising, this is not unique in Goya’s work. During the period of political upheaval in Spain at the turn of the 19th century, Goya – and other artists – had to be resourceful and adapt to circumstance, recycling canvases as their patrons fell in and out of political favour. Doña Isabel de Porcel must have been painted soon after the underlying portrait, since no dirt is visible between the paint layers of the two figures. A clearer image of the underlying portrait has recently been obtained by using an X-ray fluorescence scanning spectrometer, a cutting-edge piece of analytical technology on loan to the National Gallery through collaboration with Delft University of Technology, which maps the chemical elements in the paint.

Letizia Treves, National Gallery Curator of Italian and Spanish Paintings 1600-1800, says:

“Goya is one of the most admired and imitated painters in the history of art. Pastiches and forgeries of his works proliferated on the European and American art market in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The technical studies and provenance information regarding the Portrait of Doña Isabel de Porcel are inconclusive so far as Goya’s authorship is concerned, and the attributional status of the painting rests largely on perceptions of quality and on how close it comes to works that are indisputably by the artist – something we all have a unique opportunity to explore during the exhibition Goya: The Portraits. If it is a pastiche, it has been carried out with such impressive skill that its long-standing attribution to Goya has convinced several generations of specialists and gallery visitors.”

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Martín Zapater

1797

Oil on canvas

83 x 65cm

Bilbao Fine Arts Museum

© Bilboko Arte Ederren Museoa-Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Ferdinand VII in Court Dress

1814-1815

Oil on canvas

208 x 142.5cm

Museo Nacional del Prado. Madrid

© Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

Francisco de Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828)

Don Valentín Bellvís de Moncada y Pizarro

around 1795

Oil on canvas

115 x 83cm

Fondo Cultural Villar Mir, Madrid

© Fondo Cultural Villar Mir, Madrid

The National Gallery

Trafalgar Square, London WC2N 5DN

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 6pm

Friday 10am – 9pm

![Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828) 'Raging Lunatic (Loco furioso), Bordeaux Album I, G, 3[4?]' 1824-1828 Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746-1828) 'Raging Lunatic (Loco furioso), Bordeaux Album I, G, 3[4?]' 1824-1828](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/11-raging-lunatic-web.jpg?w=788)

You must be logged in to post a comment.