Exhibition Dates: 3rd June – 7th December, 2024

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Swimming pool, Welch, West Virginia

1958, printed c. 1987

Gelatin silver print

What a pleasure it is to present the work of the renowned American photographer O. Winston Link (1914-2001) on this archive. I’ve only ever posted on one exhibition of his work before, way back in 2009.

I’ve always loved steam trains ever since I was denied a Hornby train set as a kid. I love their scale, design, colour, noise, smell … and their muscularity. As a machine emerging from the early days of the Industrial Revolution there is something so essential and raw about them.

Link’s elaborately staged, choreographed even, large format photographs in which he employs large banks of synchronised flash lights to capture the locomotives in action, mainly at night – have a visceral effect on me, stirring up deep passions for this primordial machine.

Link’s previsualisation was strong. As Tom Garver observes, “Winston Link innately possessed what has been called photographic vision, the ability to visualise photographs before they are created and to recognise in the process that what one sees, no matter how interesting, does not necessarily translate into an interesting photograph.”

It was Link’s ability to capture the spirit and essence of the tableaux vivants, the “living picture”, that brings these static scenes alive. You can almost reach out and touch these Jurassic trains, these workhorses trundling through small American communities. Again, Tom Garver insightfully notes that “there was this great intense spirit to really document and record this, to capture it. I think what I didn’t realise is how much we were capturing a whole way of life that was disappearing. Not only steam locomotives versus diesel locomotives but this isolated small town individualised kind of America that was vanishing.”

The spirit of the thing itself.

As Minor White says in one of his ‘Three Canons’:

Be still with yourself

Until the object of your attention

Affirms your presence

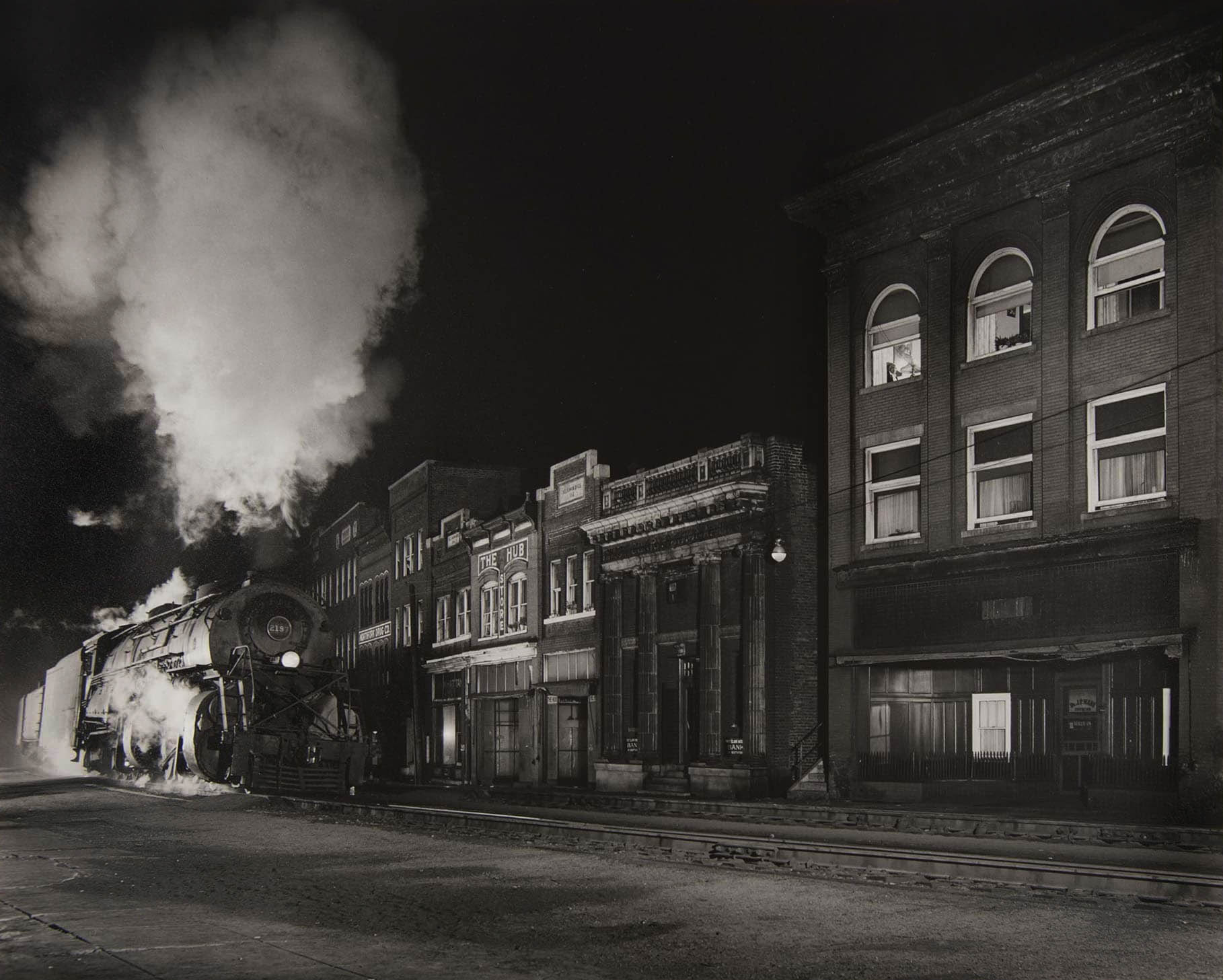

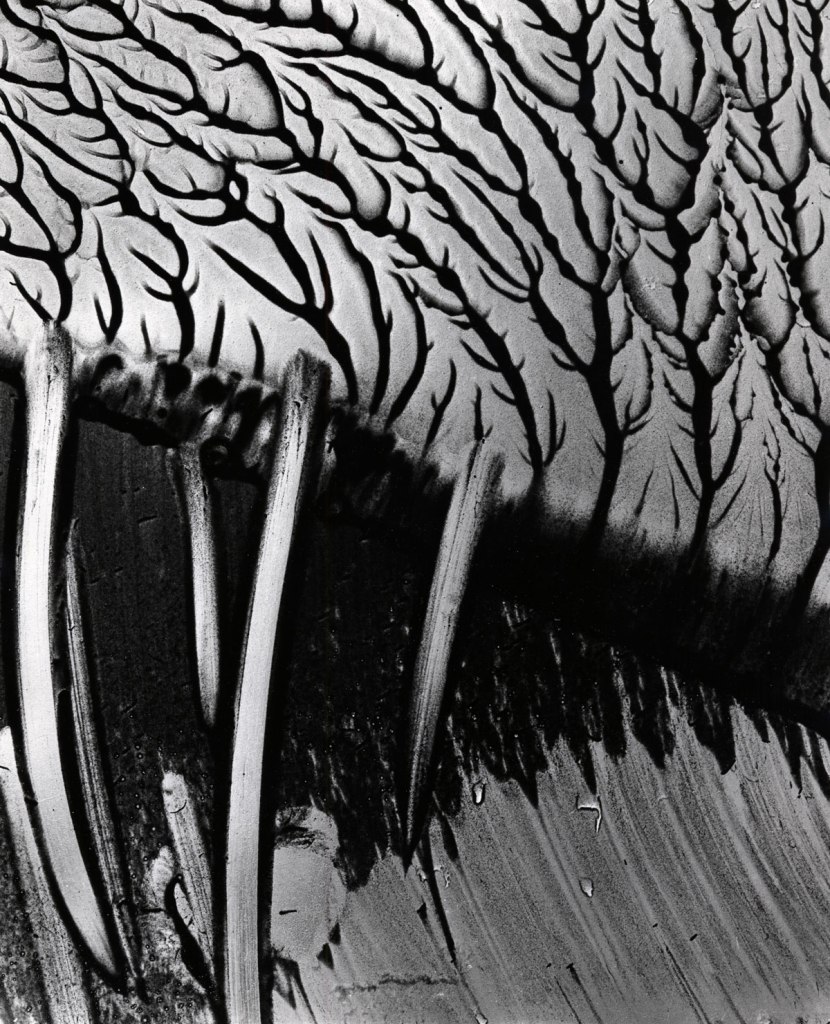

Then you look at magnificent photographs such as Locomotive Driving Wheels (1955, printed 1993?, below) with its low perspective of the enormous wheels and the light falling on the metal; the dark, disturbing creatures in Coaling Locomotives, (Puff of Steam) Shaffers Crossing Yards, Roanoke, Virginia (1955, below) like fire breathing dragons; or the incongruous sight of the train as big as the buildings and running right next to them in Main Line on Main Street, North Fork, West Virginia, August 29, 1958 (1958, printed 1997, below) – and you go… YES!

This artist gets it. He gets he gets it he gets it. And he has the skill and this really great intense spirit and the dedication to apply that skill and spirit… in order to capture the presence of these vanishing machines and worlds.

O. Winston Link … thank you.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the Jane Lutnick Fine Arts Center, Haverford College for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I can’t move the sun – and it’s always in the wrong place – and I can’t even move the tracks, so I had to create my own environment through lighting.”

O. Winston Link

“Winston’s spirit so imbued the project that it was never really work. It was such a pleasure, there was also that kind of tingle that this was high adventure. You know, you had to get it. There were times when we would be absolutely exhausted, I remember once, we arrived at a place to tape record in this case, we got there at six and discovered that the train had left at five, we got there the next day at five and discovered it had left at four, we got there at four and that time it didn’t come until midnight. So, we sat there and waited and talked about what we were doing and about life and how it was changing and the many varieties of architecture and construction and the quality of things, how they were disappearing. So, there was this great intense spirit to really document and record this, to capture it. I think what I didn’t realise is how much we were capturing a whole way of life that was disappearing. Not only steam locomotives versus diesel locomotives but this isolated small town individualised kind of America that was vanishing.”

Tom Garver, Curator and Museum Director, a former assistant for Link’s photo projects.

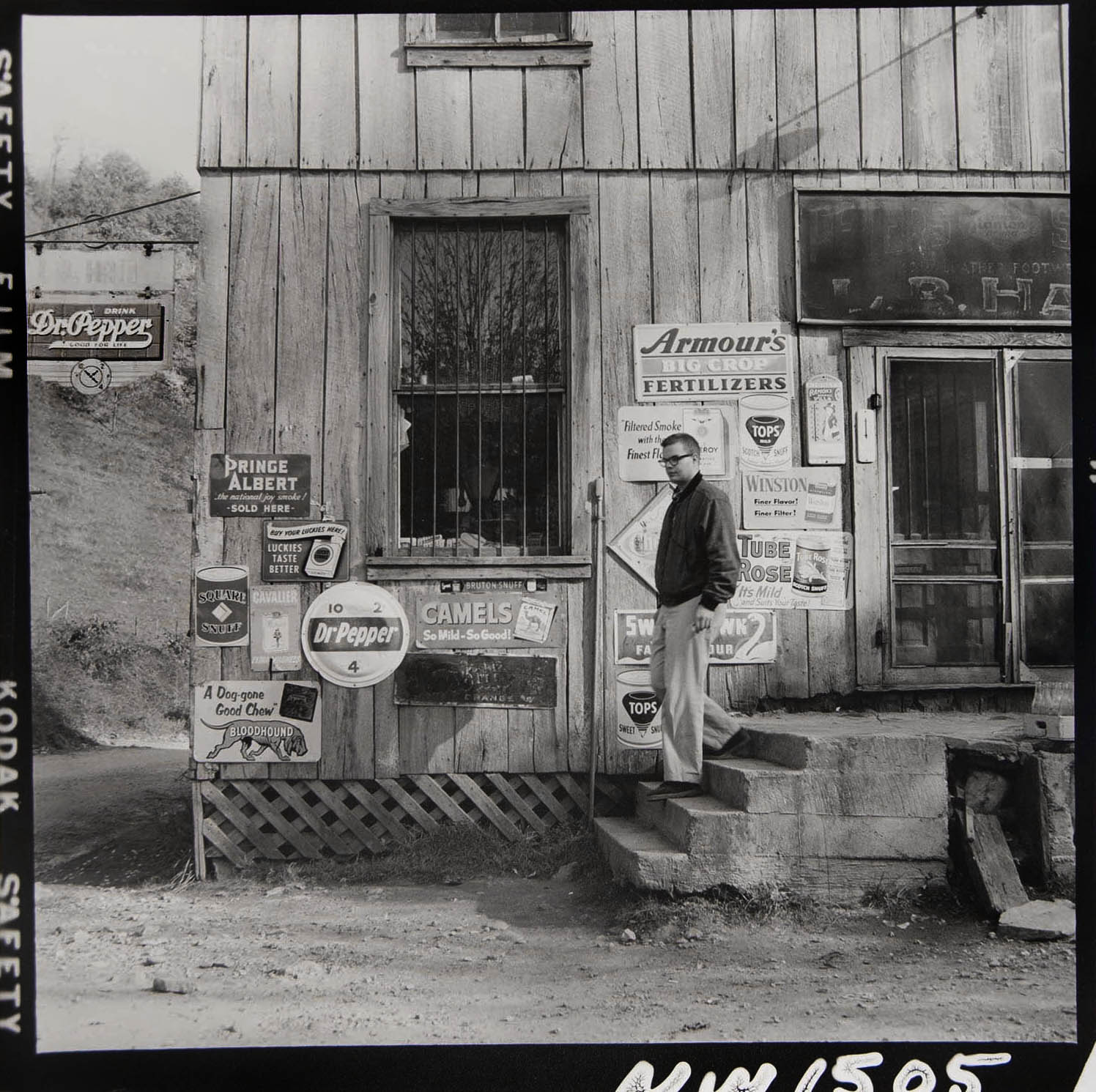

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Tom Garver at the General Store, Husk (Nella), North Carolina, 1957

1957

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Haverford Chemistry Lecture

1952

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Locomotive Driving Wheels

1955, printed 1993?

Gelatin silver print

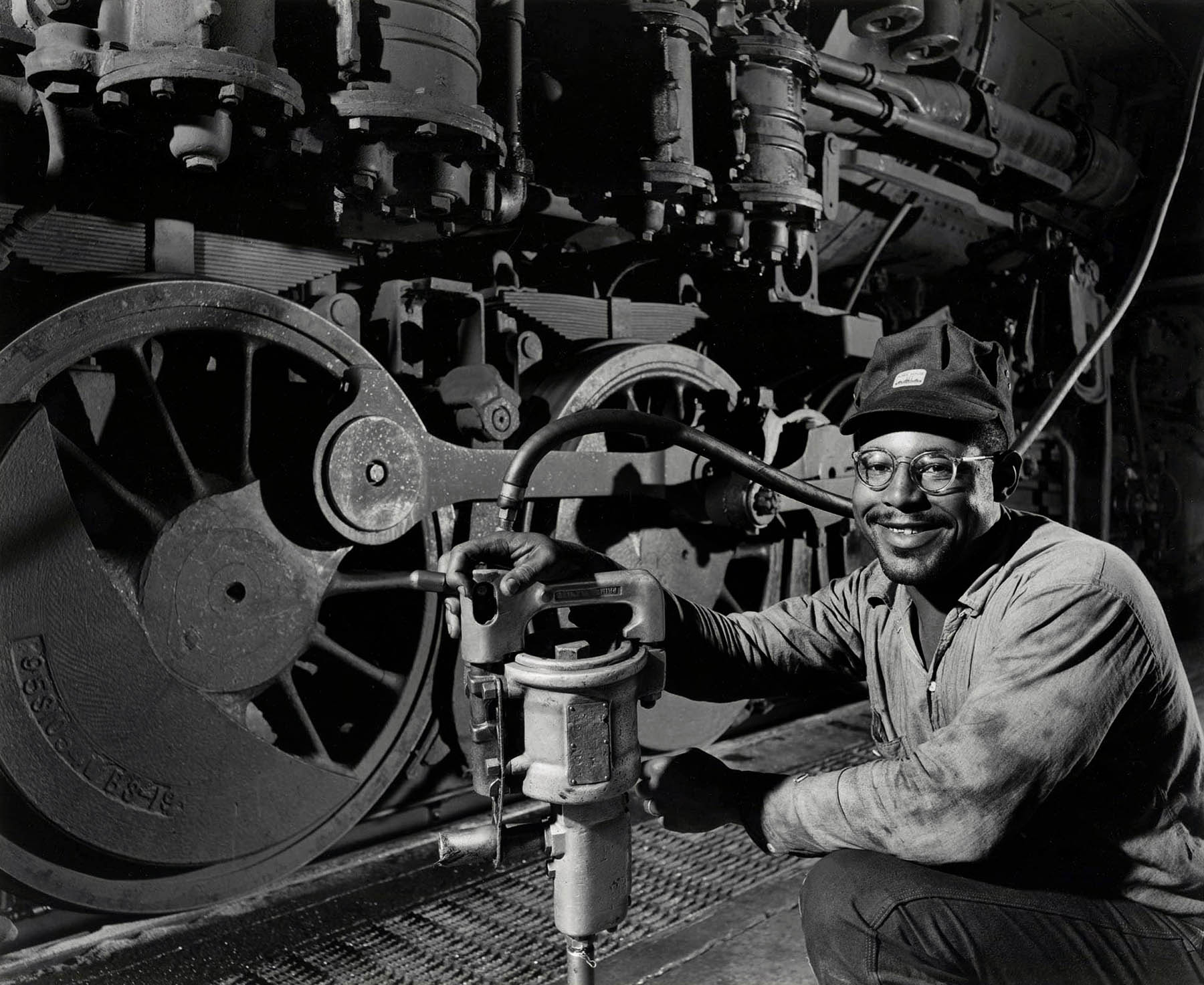

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

J. O. Hayden with His Grease Gun, Bluefield Lubritorium

1955

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Ralph White, Abingdon Branch Train Conductor, and Laundry on the Line, Damascus

1955

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Coaling Locomotives, (Puff of Steam) Shaffers Crossing Yards, Roanoke, Virginia

1955

Gelatin silver print

The exhibition consists of photographs by O. Winston Link (1914-2001) of steam locomotion on the Norfolk and Western Railroad from 1955 to 1960 and photographs taken by Link in 1952 of Haverford College for publicity purposes. Thomas “Tom” Haskell Garver (1934-2023) Haverford class of 1956 first met Link in 1952. Garver recalled that first meeting like this. “Link, a New York photographer, created admissions brochure photos at Haverford in 1952. After graduation, I was studying in New York City and worked part time for him for about a year. This included three trips with Winston to work on his documentation of the last years of steam powered railroading.”

Garver, an accomplished museum administrator and curator, stepped in when Link needed a friend and supporter. Forty years after Garver first met Link his life was marred by tragedy. Conchita Mendoza Link, his second wife, who also was her husband’s agent, fabricated a story that Link suffered from Alzheimer’s Disease in an attempt to steal from Link payments for his work. Mrs. Link was also found to have stolen many of Link’s negatives and prints from which she pocketed the money from their sale. Mrs. Link was criminally charged, found guilty, and sentenced to prison in 1996. Garver began to assist again Link by becoming his business agent. After Link’s death Garver became the organising curator of the O. Winston Link Museum in Roanoke, Virginia. The Last Steam Railroad in North America, published in 1995 by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. and authored by Garver is the definitive publication on Link and his photography.

Garver wrote in the book: “These photographs are, in every way, works of art,” … “Winston Link innately possessed what has been called photographic vision, the ability to visualise photographs before they are created and to recognise in the process that what one sees, no matter how interesting, does not necessarily translate into an interesting photograph. The thing photographed and a photograph of it are coequal neither in interest, nor in appearance.” Garver’s efforts were instrumental on so many levels in gaining recognition for Link’s photographs as they are now recognised as some of the greatest photographs of the 20th century.

Tom Garver was a great supporter of Haverford College in all manner of ways. As an active member of the class of 1956 with each reunion cycle he compiled Class of 1956 Collective Biography. Furthermore, in his case, that also meant contributing hundreds of art photographs to the Fine Art Photography Collection. Manuscripts including letters from Paul Strand and George Segal and documentary photographs of American scenes by Charles Currier, who was the subject of Garver’s Master’s thesis to further support Special Collections at Haverford. Among this bounty of collections of photographs are a choice selection of O. Winston Link’s black and white, and colour photographs. This exhibition is a fitting memorial to a loyal and generous alumnus.

Text from the Jane Lutnick Fine Arts Center, Haverford College website

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Hotshot Eastbound, Iaeger, West Virginia, 1956

1956, printed 2001

Gelatin silver print

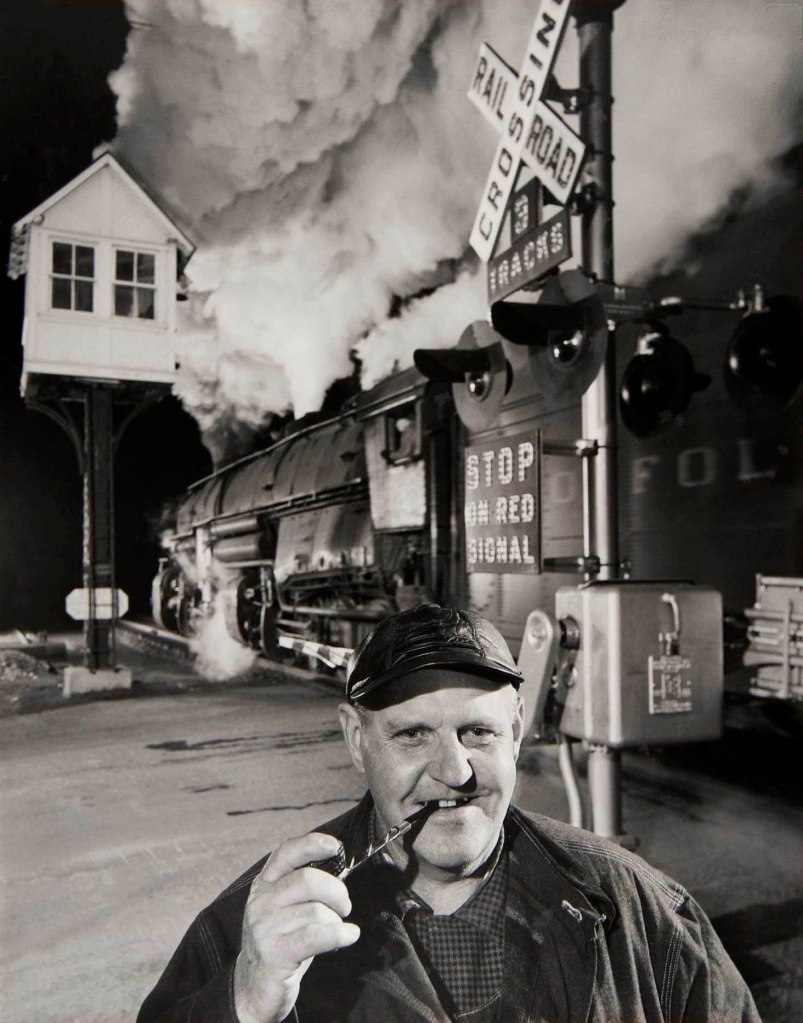

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Archie Stover, Crossing Watchman

1956

Gelatin silver print

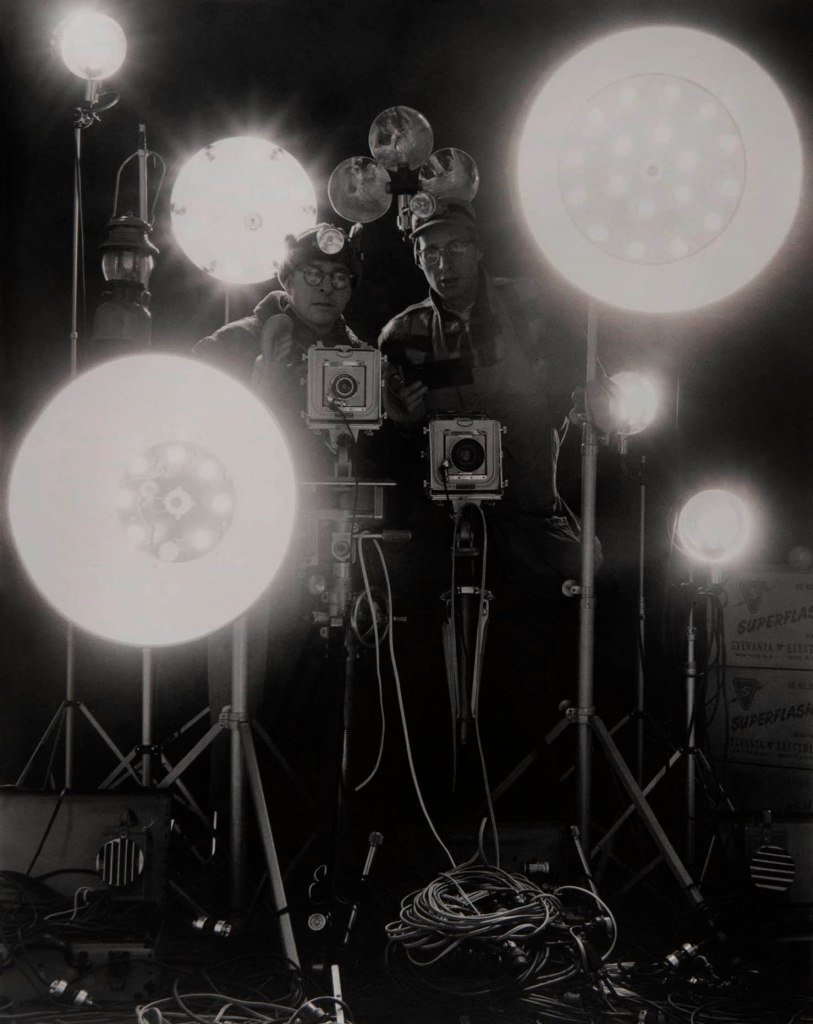

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Winston Link, George Thom and Night Flash Equipment: All Flashbulbs Firing

1956

Gelatin silver print

Preserving the Golden Age of Railroads

In the 1950s, O. Winston Link, a photographer with an astute affinity for technical photography and a fond fascination with trains, set out to record the last steam locomotives operating in the country. After contacting the Norfolk and Western Railway and gaining access to the company’s premises, Link would begin recording the last surviving fleet of locomotives against the night sky, preserving the golden age of railroads and the remaining vestiges of American 20th-century industry. …

Staunton, Virginia

In 1955, O. Winston Link would begin exploring a series of photographs that would have a lasting impact on the medium’s history. After accepting a job that would take him to Staunton, Virginia, Link noticed the Norfolk and Western Railway, the last major steam railroad in the country. The company was ceasing operations as an industry-wide change from steam to diesel was in effect. Link was further impressed by the human connection to the railroad, a thread of sparsely spread communities that lived near the tracks. The photographer noticed not only the facilities and locomotives but the trackside communities that were profoundly immersed with the steam locomotives and rail transportation.

From 1955 to 1960, Winston Link returned to Virginia around 20 times. He photographed the clouds of steam and massive steel bodies of the locomotives passing through the Virginian and Appalachian communities, documenting some of the last days of the steam engine. In this unique quest, Link traveled by night covering a large swath of area, from Virginia and North Carolina to Maryland. With his preference for capturing the locomotives at night and prior experience with highly technical photographs for corporate clients, Link had the aptitude to develop a unique flash photography system. His unique system rigged flashbulbs, sometimes up to 80 of them, to fire simultaneously and allow the camera to capture the high-speed trains moving past his frame at night. As to why he chose to take his pictures at night, the photographer notedly said:

“I can’t move the sun – and it’s always in the wrong place – and I can’t even move the tracks, so I had to create my own environment through lighting.” ~ O. Winston Link

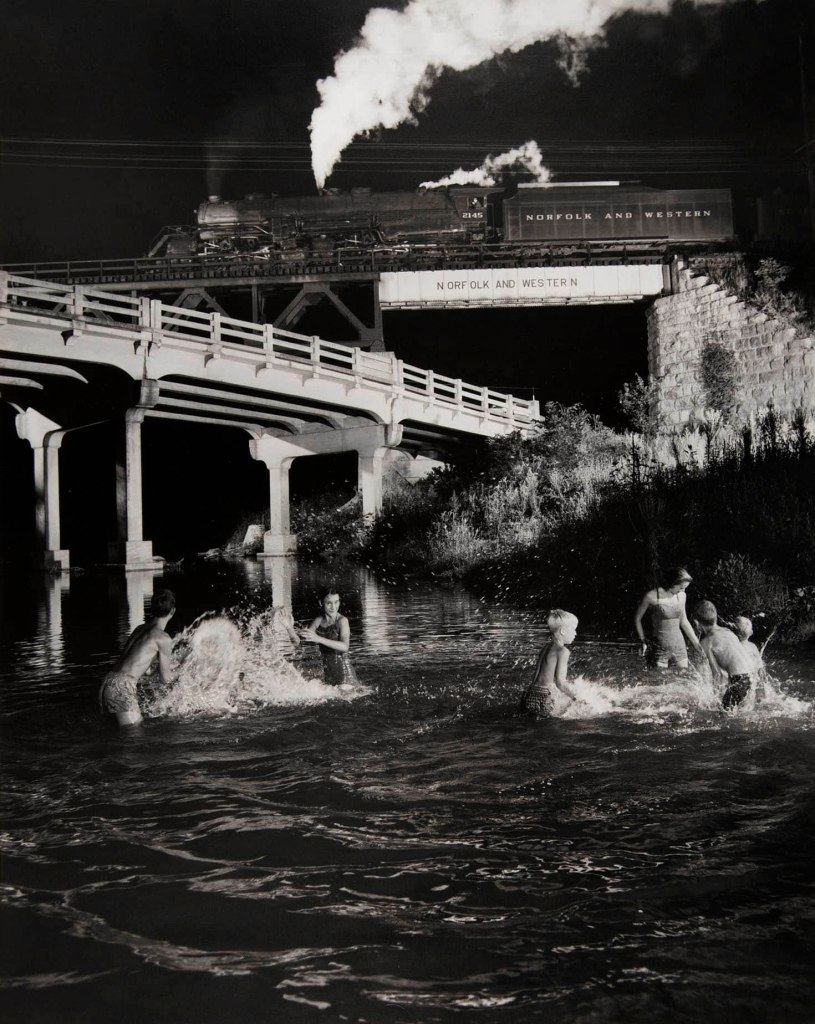

O. Winston Link’s perseverance in recording the nightly locomotives that passed Appalachia made him a pioneer not only for his subject matter but also as a trailblazer in night photography. Most likely inspired by his legendary predecessor, the Hungarian-French photographer Brassai, who captured the underbelly of Paris by night, Winston Link’s contributions to the preservation of American history helped chronicle these once, one-of-a-kind towns. Whether at the drive-in, splashing in the river below a railway bridge, pumping gas trackside by a passing locomotive, or directing a train through the quiet night of the rural countryside, Link’s pictures conserve small towns, whose lives revolved around the coming and going of steam engines. Through the rising pillars of steam, the sounds of bells and whistles announcing the arrival of the steam engines, and the camaraderie of community members in his pictures, Winston Link preserves a romantic, golden age of American railroads. When asked what about steam engines he found so appealing, Link said:

“I guess it’s because of the places they go. They’re always going through some mountains, through the valleys, and through the rivers, and forests, it’s always country. And I’ve lived in New York City, in Manhattan and Brooklyn, where you didn’t have anything like that. So, it’s always great to get on a train and take a long trip. I suppose that’s part of it. And the sounds that it makes, the smells that it has. It has a bell in it, it has air pumps, and it has valves that are releasing shots of steam every now and then. It has a turbo, which has a whine to it. It has a beautiful whistle, the old steam engines had different whistles, all had different characteristics and different sounds. And they had smells from hot grease and oil, the smell of coal smoked, the soft coal, has a nice smell to it as long as you don’t get it blasted in the face, as long as you’re far away from it, its Ok. It’s things like that. The sound of the wheels, the sound of the drivers, you can tell exactly what’s happening to the engine, and how fast its going, if the rods are lose, it makes different sounds. So, it has all these characteristics. The diesel engine is great, it’s very efficient, there’s nothing like them but, it’ll never replace a steam engine.” ~ O. Winston Link, 1980s

Holden Luntz. “O. Winston Link’s Birmingham Special, Rural Retreat, Virginia,” on the Holden Luntz Gallery website October 12, 2012 [Online] Cited 11/10/2024

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Main Line on Main Street, North Fork, West Virginia, August 29, 1958

1958, printed 1997

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Hawksbill Creek Swimming Hole, Luray, Virginia, 1956

1956

Gelatin silver print

Further O. Winston Link photographs from the Norfolk and Western Railroad

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Y-6 Locomotive on the Turntable, Shaffers Crossing Yards, Roanoke, Virginia

1955, printed 1994

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Norfolk and Western Railway

1955

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Locomotive 261

1955

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Train #2 arrives at the Waynesboro Station, Waynesboro, Virgnia, April 14, 1955

1955, printed 1996

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Sometimes the Electricity Fails, Vesuvius, Virginia, 1956

1956, printed 1988

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Maud Bows to the Virginia Creeper

1956

Gelatin silver print

O. Winston Link (American, 1914-2001)

Birmingham Special, Rural Retreat, Virginia, 1957

1957, printed 1986

Gelatin silver print

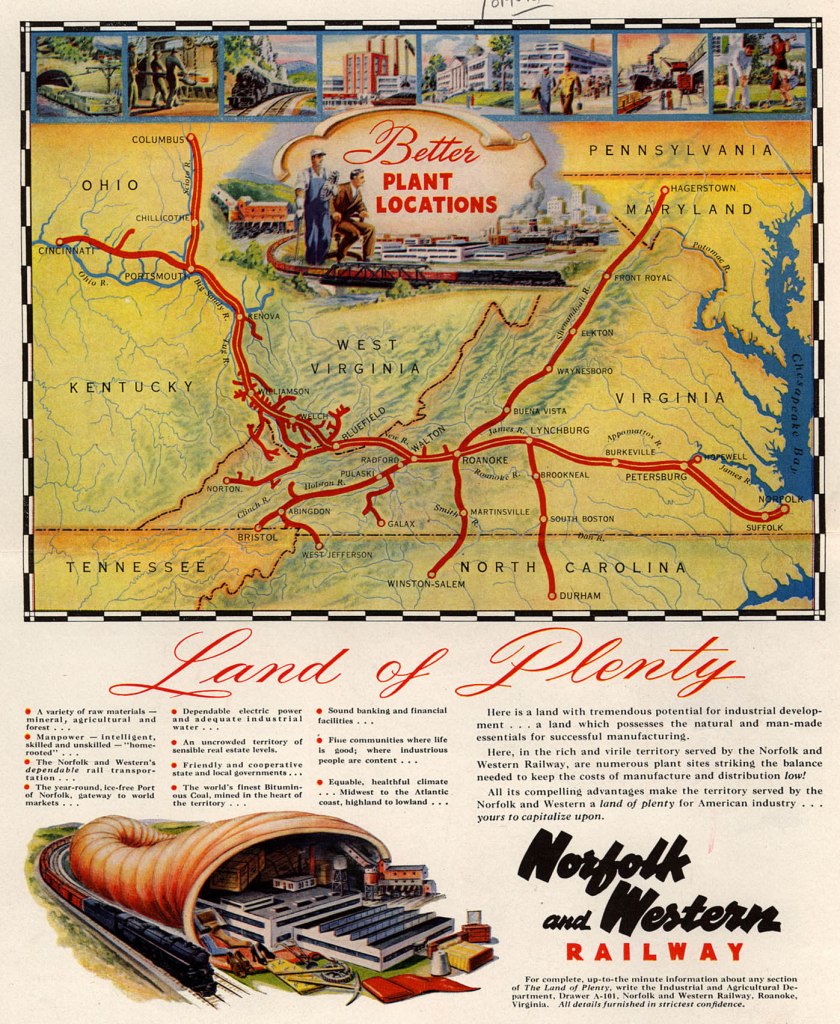

1948 Norfolk and Western Railway – Land of Plenty

Norfolk and Western magazine ad with system map

1948

Duke University Libraries

Public domain

Haverford College

370 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, PA 19041

Monday – Friday, 9am – 5pm

Weekends, Noon – 5pm

You must be logged in to post a comment.