Exhibition dates: 8th June – 12th September 2012

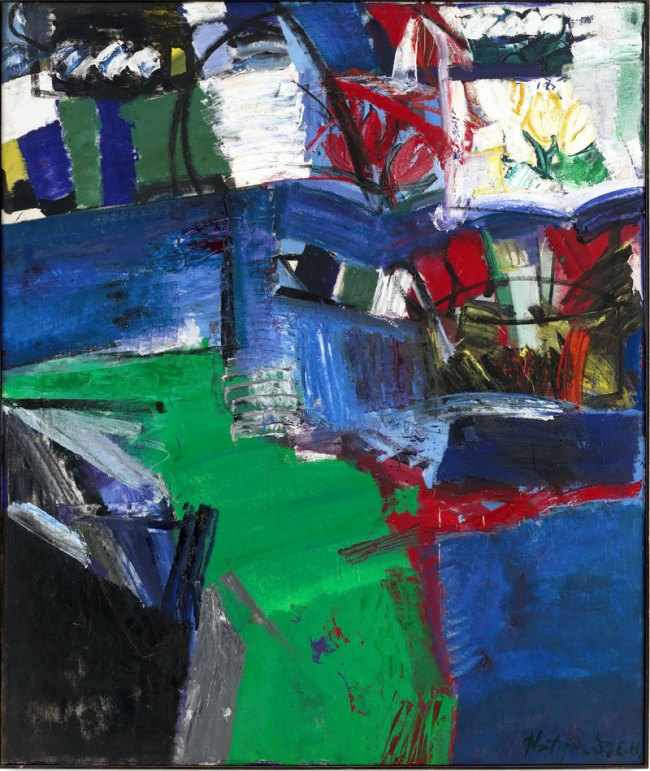

Grace Hartigan

(American, 1922-2008)

Ireland

1958

Oil on canvas

200 x 271cm

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

© Grace Hartigan Estate

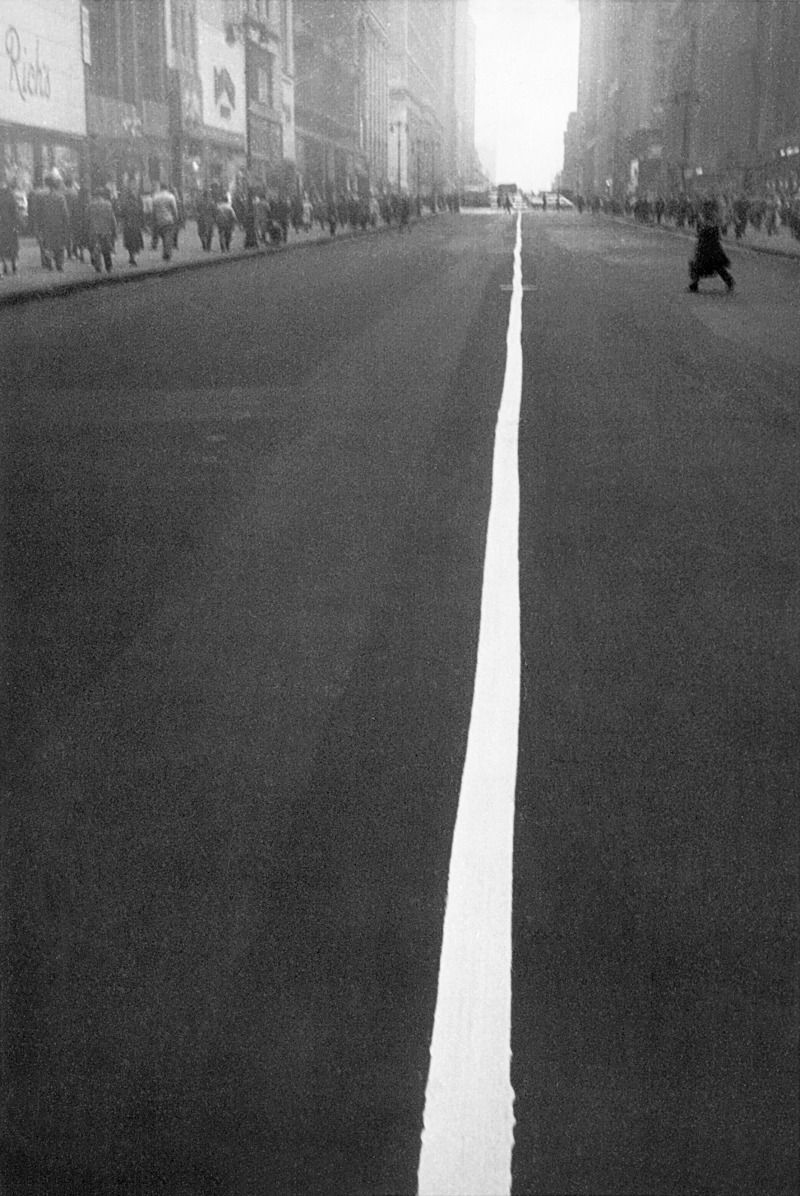

This is pure indulgence. These paintings are so delicious I couldn’t resist a posting. Just imagine having ANY of them (especially the Hartigan, de Kooning or the Soulanges) on your wall at home… oh my!

Marcus

Many thankx to the Guggenheim Museum for allowing me to publish the pictures in the posting. Please click on the pictures to see a larger version of the image.

Art of Another Kind: International Abstraction and the Guggenheim, 1949-1960

Curators Tracey Bashkoff and Megan Fontanella discuss the initial apprehensions toward and eventual return to international exchange and experimentalism that defined the postwar art world.

Alberto Burri (Italian, 1915-1995)

Composition

1953

Burlap, thread, synthetic polymer paint, gold leaf, and PVA on black fabric

86 x 100.4cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

In 1943 Alberto Burri, a doctor in the Italian army, was captured by the British and sat out the remainder of World War II in a Texas POW camp. He began to paint there, covering his stretchers with burlap when other materials were unavailable. Upon his return to Italy in 1946 Burri renounced his original profession and dedicated himself to making art.

Composition is one of his Sacchi (sacks), a group of collage constructions made from burlap bags mounted on stretchers, which the artist began making in 1949. One of Burri’s first series employing nontraditional mediums, the Sacchi were initially considered assaults against the established aesthetic canon. His use of the humble bags may be seen as a declaration of the inherent beauty of natural, ephemeral materials, in contradistinction to traditional “high” art mediums, which are respected for their ostentation and permanence. Early commentators suggested that the patchwork surfaces of the Sacchi metaphorically signified living flesh violated during warfare – the stitching was linked to the artist’s practice as a physician. Others suggested that the hardships of life in postwar Italy predicated the artist’s redeployment of the sacks in which relief supplies were sent to the country.

Yet Burri maintained that his use of materials was determined purely by the formal demands of his constructions. “If I don’t have one material, I use another. It is all the same,” he said in 1976. “I choose to use poor materials to prove that they could still be useful. The poorness of a medium is not a symbol: it is a device for painting.” The title Composition emphasises the artist’s professed concern with issues of construction, not metaphor. Underlying the work is a rigorous compositional structure that belies the mundane impermanence of his chosen mediums and points to art-historical influences. The Sacchi rely on lessons learned from the Cubist- and Dada-inspired constructions of Kurt Schwitters.

Despite Burri’s cool public stance, the Sacchi are examples of the Expressionism widely practiced in postwar Europe, where such work was called Art Informel (in the U.S. it was called Abstract Expressionism). Artists used powerfully rendered gestures and accommodated chance occurrences to express the existential angst characteristic of the period.

Jennifer Blessing

Text from the Guggenheim website

Antoni Tàpies (Spanish, 1923-2012)

Great Painting

1958

Oil with marble dust and sand on canvas

79 x 103 1/2 inches (200.7 x 262.9cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© 2018 Fundació Antoni Tàpies/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VEGAP, Madrid

In the years after World War II, both Europe and America saw the rise of predominantly abstract painting concerned with materials and the expression of gesture and marking. New Yorkers dubbed the development in the United States Abstract Expressionism, while the French named the pan-European phenomenon of gestural painting Art Informel. A variety of the latter was Tachisme, from the French word tache, meaning blot or stain. Antoni Tàpies was among the artists to receive the label Tachiste because of the rich texture and pooled colour that seemed to occur accidentally on his canvases.

Tàpies reevaluated humble materials, things of the earth such as sand – which he used in Great Painting (Gran pintura, 1958) – and straw as well as the refuse of humanity such as string and bits of fabric. By calling attention to this seemingly inconsequential matter, he suggested that beauty can be found in unlikely places. Tàpies saw his works as objects of meditation that every viewer will interpret according to personal experience; he sought to inspire a contemplative reaction to reality through the integration of materials unexpected in fine art.

These images often resemble walls that have been scuffed and marred by human intervention and the passage of time. In Great Painting, an ocher skin appears to hang off the surface of the canvas; violence is suggested by the gouge and puncture marks in the dense stratum. These markings recall the scribbling of graffiti, perhaps referring to the public walls covered with slogans and images of protest that the artist saw as a youth in Catalonia – a region in Spain that experienced the harshest repression under dictator Francisco Franco. Tàpies called walls the “witnesses of the martyrdoms and inhuman sufferings inflicted on our people.”1 Great Painting suggests the artist’s poetic memorial to those who have perished and those who have endured.

Jennifer Blessing

1/ Antoni Tàpies, La pratique de l’art (Paris: Gallimard, 1974), p. 59.

Text from the Guggenheim website

Kenzo Okada (Japanese, 1902-1982)

Decision

1956

Oil on canvas

67 3/4 x 80 inches (172.8 x 203.2cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, Susan Morse Hilles, 1981

© Kenzo Okada

After Kenzo Okada relocated from Tokyo to New York in 1950, his work came to represent a melding of Japanese traditions and American abstract trends. Rather than striving for pure abstraction, his work from the 1950s could be called “semi-abstract,” evoking the natural world through carefully composed form and a decidedly muted palette. These works are subtle, quiet, and poetic – more meditative in nature than the energetic gestural abstractions of some of his American-born counterparts. The composition of Decision (1956) is also organised to suggest natural topography. Blocky, softly defined shapes organically arrange the canvas into rough horizontal registers, creating a panoramic quality reminiscent of landscape painting. Meanwhile, small, irregular shapes hover and tumble rhythmically across the stable ground. Okada thus seeks a balance between heavy and delicate, tangible and abstract.

Text from the Guggenheim website

José Guerrero (Spanish, 1914-1991)

Signs and Portents

1956

Oil on canvas

175.9 x 250.2cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VEGAP, Madrid

© The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Kumi Sugaï (Japan, 1919-1996)

Shiro

June 1957

Oil on canvas

63 5/8 x 51 inches (161.6 x 129.5 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© Kumi Sugaï

Kumi Sugaï lived and worked in Paris from 1952 until his death. Revered both in his native Japan and France, he used his early fascination with modern typography and his knowledge of East Asian calligraphy in his work. Combining and reinventing traditional aesthetics and contemporary forms, Sugaï reveals his syncretic approach to abstract painting in Shiro (June 1957). Here, his palette is restricted essentially to black, white, and blue, and the composition is at once spare and dynamic. The painting’s title is a reference to its central black form, the ideogram shiro, which means white. He has enlarged the character to occupy the entire composition and placed this abstract form on a white ground, both evoking and distorting its original calligraphic source.

Text from the Guggenheim website

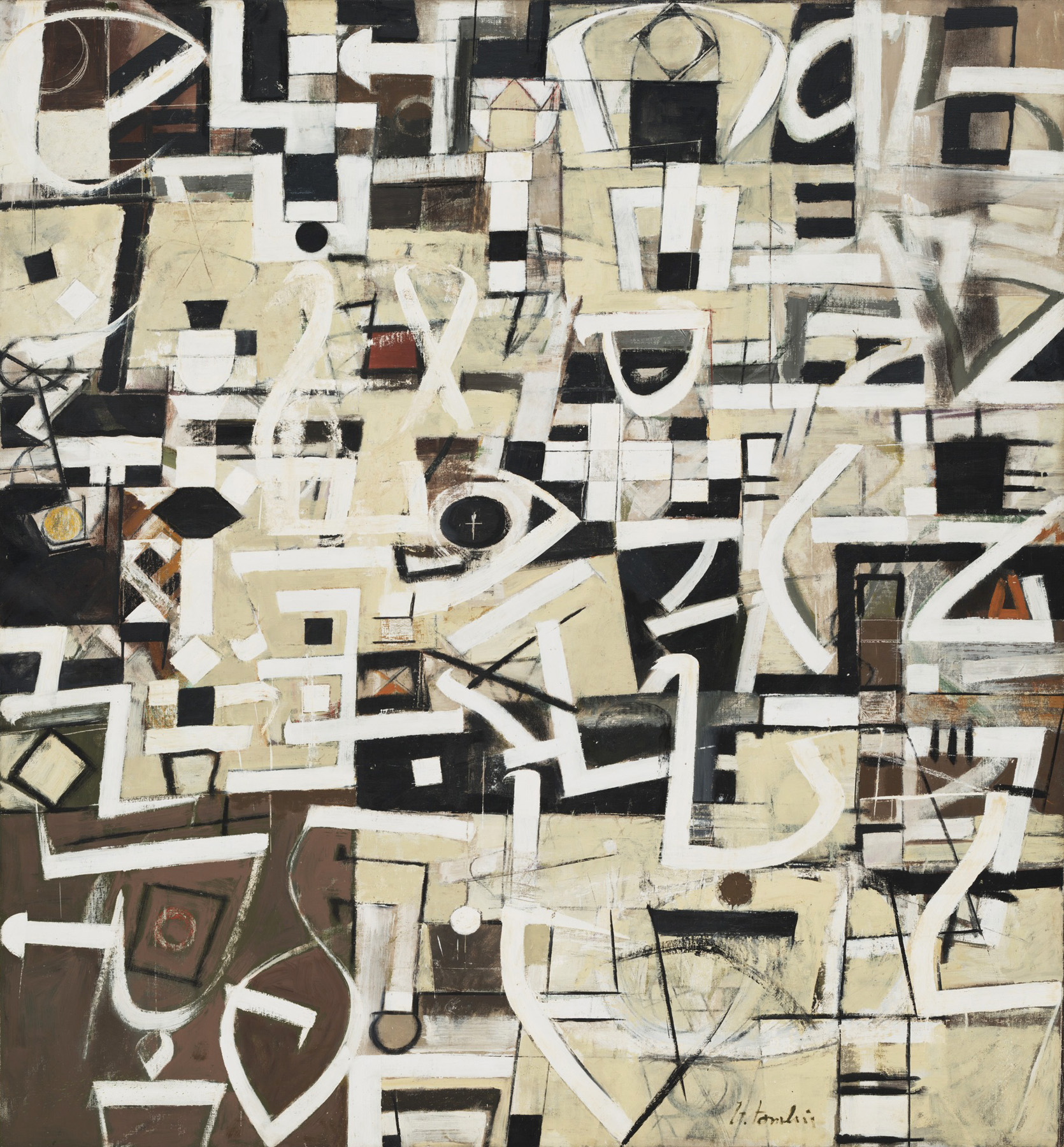

Giuseppe Capogrossi (Italian, 1900-1972)

Surface 210

1957

Oil on canvas

81 1/4 x 63 inches (206.4 x 160cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome

A decisive shift in Giuseppe Capogrossi’s career took place in 1949, when he moved away from figurative, tonal painting and experimented with an abstract geometric style that led to the development of a vocabulary of irregular comb- or fork-shaped signs. With no allegorical, psychological, or symbolic meaning, these structural elements could be assembled and connected in countless variations. Intricate and insistent, Capogrossi’s signs determined the construction of the pictorial surface. Similar to mysterious lists or sequences, his paintings were immediate in their appeal yet remained hard to decode, a quality he shared with other Art Informel practitioners. These abstract comb-sign paintings, known simply as Surfaces (Superficies, 1949-1972), were first exhibited at the Galleria del secolo, Rome, in 1950. The comb sign dominated his oeuvre until the end of his career.

Text from the Guggenheim website

Takeo Yamaguchi

(Japanese, 1902-1983)

Work – Yellow (Unstable Square [Fuantei shikaku])

1958

Oil on plywood

182.6 x 182.6cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© Takeo Yamaguchi

In his native Japan, Takeo Yamaguchi was a pioneer of modern abstract painting. This focus led him to spend time in France, where he was much influenced by the work of Cubist practitioners in Paris, until he returned to Japan in 1931. In the 1950s, Yamaguchi began executing works consisting of simple, geometric forms – largely yellow, ochre, or russet in color – painted on a black background. His thick pigments added texture to the monochromatic compositions, and as seen in Work – Yellow (Unstable Square [Fuantei shikaku], 1958), Yamaguchi’s abstract shapes increasingly dominated the canvas. It is noteworthy that the painting was prominently displayed on the ground floor of the Guggenheim’s rotunda during the 1959 inaugural exhibition, attesting to then-director James Johnson Sweeney’s keen interest in Yamaguchi’s work.

Text from the Guggenheim website

Pierre Soulages

(French, b. 1919)

Painting, November 20, 1956 (Peinture, 20 novembre 1956)

1956

Oil on canvas

195 x 130.2cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

Pierre Soulages, a leading proponent of Tachisme (from the French word tache, meaning blot or stain), maintained that he decided to become a painter while inside the church of Sainte-Foy in Conques-en-Rouergue, near his birthplace in the South of France. The impressions of monumentality, stability, primitive force, and clearly organised volumes characteristic of the Romanesque style, as well as the mystery and sobriety of dark church interiors, were metaphorically transmitted in his mature style. Early on he was also drawn to the work of Claude Lorraine and Rembrandt van Rijn, whose rendering of light had an impact on his development. In 1938 he moved to Paris to prepare for the entrance exam to the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, but he soon abandoned his traditional studies at the school as a result of seeing exhibitions of the work of Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso and visiting the Louvre.

In his earliest work Soulages took leafless winter trees as his point of departure. Their essential, reduced network of branches – which Soulages regarded as abstract sculpture – provided him with an ideal vehicle for the exploration of structure and variation. During the German occupation of France, he met Sonia Delaunay, who introduced him to abstract art and set him on a new path. By the mid 1950s, Soulages had switched from a small brush, with which he had painted abstract calligraphic patterns, to palette knives, straightedges, and large house-painting brushes. These tools afforded him a greater range of motion in his wrist, allowing him to produce bold, dynamic strokes that resulted in a more gestural surface. Throughout his career, Soulages painted in a predominately black palette in order to explore the contrasts of light and shade, which endowed his paintings both an architectonic and a sculptural quality. In Painting, November 20, 1956 (Peinture, 20 novembre 1956, 1956), Soulages divided his canvas into three horizontal registers, articulating each with a repetition of slab-like black shapes that reveal a variety of red and brown nuances, as well as a certain luminosity.

Text from the Guggenheim website

From June 8 to September 12, 2012, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum presents Art of Another Kind: International Abstraction and the Guggenheim, 1949-1960. Comprising approximately 100 works by nearly 70 artists, the exhibition explores international trends in abstraction in the decade before the Guggenheim’s iconic Frank Lloyd Wright-designed building opened in October 1959, when vanguard artists working in the United States and Europe pioneered such influential art forms as Abstract Expressionism, Cobra, and Art Informel. In the 1950s, many countries ended their postwar isolationism and entered a phase of cultural openness and internationalism. The prominent French art critic Michel Tapié declared the existence of un art autre (art of another kind), a term embracing a mosaic of styles, but essentially signifying an avant-garde art that rejected a connection with any tradition or past idiom. With works by Karel Appel, Louise Bourgeois, Alberto Burri, Eduardo Chillida, Lucio Fontana, Grace Hartigan, Asger Jorn, Yves Klein, Willem de Kooning, Georges Mathieu, Isamu Noguchi, Kenzo Okada, Jackson Pollock, Pierre Soulages, Antoni Tàpies, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Takeo Yamaguchi, and Zao Wou-Ki, among others, the exhibition considers the artistic developments of the post-World War II period and draws greater attention to lesser-known artists in the museum?s collection alongside those long since canonised.

Abstract Expressionism encompasses a diverse range of postwar American painting that challenged the tradition of vertical easel painting. Beginning in the late 1940s, Pollock placed his canvases on the floor to pour, drip, and splatter paint onto them. This gestural act, with variations practiced by William Baziotes, De Kooning, Adolph Gottlieb, and others, was termed “Action painting” by American critic Harold Rosenberg, who considered it a product of the artist’s unconscious outpouring or the enactment of some personal drama. The New York school, as these artists were called due to the city’s postwar transformation into an international nexus for vanguard art, expanded in the 1950s with the unique contributions of such painters as James Brooks and Hartigan, as well as energetic collagist-assemblers Conrad Marca-Relli and Robert Rauschenberg. Other painters eliminated the gestural stroke altogether. Mark Rothko used large planes of colour, often to express universal human emotions and inspire a sense of awe for a secular world. Welder-sculptors such as Herbert Ferber and Theodore Roszak are also counted among the decade’s pioneering artists.

The postwar European avant-garde in many ways paralleled the expressive tendencies and untraditional methods of their transatlantic counterparts, though their cultural contexts differed. For artists in Spain, abstract art signified political liberation. Dissenting Italian artists correspondingly turned to abstraction against the renewed popularity of politicised realism. French artist Jean Dubuffet’s spontaneous approach, Art Brut (Raw art), retained figurative elements but radically opposed official culture, instead favouring the spontaneous and direct works of untrained individuals. His work influenced the Cobra group (1948-1951), which was founded by Appel, Jorn, and other artists from Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. The Cobra artists preferred thickly painted surfaces that married realism to lively colour and expressive line in a new form of primitivism.

Eventually taking root in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and Spain, Art Informel refers to the anti-geometric, anti-naturalistic, and nonfigurative formal preoccupations of many European avant-garde artists, and their pursuit of spontaneity, looseness of form, and the irrational. Art Informel is alternatively known by several French terms: Abstraction lyrique (Lyrical Abstraction), Art autre (Art of another kind), matiérisme (matter art), and Tachisme (from tache, meaning blot or stain). The movement includes the work of Burri and Tàpies, who employed unorthodox materials like burlap or sand and focused on the transformative qualities of matter. Asian émigré artists Kumi Sugaï and Zao were likewise central to the postwar École de Paris (School of Paris) and melded their native traditions with modern painting styles. By the end of the 1950s, artists such as Lucio Fontana, Klein, and Piero Manzoni were exploring scientific, objective, and interactive approaches, and introduced pure monochrome surfaces. Other abstractionists engaged viewers’ senses and explored dematerialisation, focusing on optical transformations as opposed to the art object itself, and investigating the effects of motion, light, and colour.

Through the presentation of these varied styles and innovative developments in the post-World War II years, Art of Another Kind especially highlights paintings and sculptures that entered the Guggenheim collection under James Johnson Sweeney, the museum’s second director (1952-1960). Following Solomon R. Guggenheim’s death in 1949 and the end of founding director and curator Hilla Rebay’s tenure in 1952, Sweeney championed emerging avant-garde artists and augmented the museum’s existing modern holdings with new works. Sweeney had stated, “I do not believe in the so-called ‘tastemakers,’ … but in what I would call ‘tastebreakers,’ the people who break open and enlarge our artistic frontiers.” His program of exhibitions and acquisitions considerably broadened the museum’s scope, and his vision included reconsidering the founding collection assembled by Solomon and Irene Guggenheim under Rebay’s guidance by uniting the abstract works by Vasily Kandinsky and other modernists with rarely seen representational works for a more complex perspective of the avant-garde in the first half of the twentieth century. Recently, the Guggenheim Museum highlighted his contributions to the institution in The Sweeney Decade: Acquisitions at the 1959 Inaugural, an exhibition featuring a selection of works that were first unveiled at the 1959 show in the museum’s new Wright building. On view in 2009 as part of the museum’s 50th-anniversary celebrations, The Sweeney Decade featured 24 paintings and sculptures from the 1950s collected under his leadership. Art of Another Kind offers a more comprehensive elaboration of his vision along with works that were added to the collection after his tenure.

Exhibition installation

While the exhibition explores individual styles, diversity within abstraction, and artists often working independently of established groups or affiliations, works are loosely organised according to artists’ locus of activity and stylistic trends: New York school; Art Brut and Cobra; School of Paris; Spanish and Italian Informalism; Kinetic art; and, finally, late 1950s experiments with matiérisme, performance-based painting, and the monochrome. Highlights within the installation include Outburst (Éclatement, 1956) by Judit Reigl, newly acquired in 2012, and Alexander Calder’s Red Lily Pads (Nénuphars rouges, 1956), suspended in the upper ramps and visible from the rotunda floor below. The exhibition also includes the work of 11 living artists.

Visitors will have the opportunity to browse through historic exhibition catalogues produced by the first full-time publications department established during Sweeney’s tenure. Designed by the Swiss-born typographer and designer Herbert Matter, catalogues from the era helped shape the museum’s visual identity and chronicle the development of the art championed by the Guggenheim under Sweeney in the 1950s. Selected books will be available in the museum at iPad stations and online at https://www.guggenheim.org/publications

Extensive content related to the exhibition will be available on the Guggenheim’s website, which features a selection of supporting materials from the museum’s archives, including letters between artists and director James Johnson Sweeney, invitations to exhibitions, and historic photos of Guggenheim exhibitions. In addition, 20 works and several exhibition themes will be explored through short texts. Multimedia content including video footage and interviews with the curators will be added to the site once the exhibition opens to the public.

Press release from the Guggenheim Museum website

Mark Rothko

(American, 1903-1970)

Untitled (Violet, Black, Orange, Yellow on White and Red)

1949

Oil on canvas

207 x 167.6cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Gift, Elane and Werner Dannheisser and The Dannheisser Foundation

© 2012 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956)

Untitled (Green Silver)

c. 1949

Enamel and aluminum paint on paper, mounted to canvas

22 3/4 x 30 3/4 inches (57.8 x 78.1cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, Sylvia and Joseph Slifka, 2004

© 2018 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the decades following World War II, a new artistic vanguard emerged, particularly in New York, that introduced radical new directions in art. The war and its aftermath were at the underpinnings of the movement that became known as Abstract Expressionism. These artists, anxiously aware of human irrationality and vulnerability, expressed their concerns in an abstract art that chronicled the ardor and exigencies of modern life. Their heroic aspirations are most evident in Jackson Pollock’s innovative “drip” paintings that forever altered the course of American art.

Arriving in New York in 1930 from the West Coast, Pollock began working with figuration of both human and imaginary beings. Most of this imagery was connected to that of American Indian sand painting and the Mexican muralists he saw as a youth and that reemerged through psychoanalysis to treat his lifelong alcoholism. His first fully mature works – dating between 1942 and 1947 – use an idiosyncratic iconography he developed in part as a response to Surrealism, popular in New York with its numerous European exiles from World War II. Employing mythical subject matter, calligraphic markings, and a vibrant and distinctive colour palette, Pollock produced emotionally charged works that retain figurative subject matter yet emphasise abstract qualities. Arising from this confluence of abstraction and figuration are Pollock’s breakthrough works, commonly perceived as pure abstraction and made over the course of an explosive period between late 1947 and 1950 as represented by Untitled (Green Silver). At the time, he also broke free from the standard use of implements, usually abandoning their direct contact with the surface. Working from above the picture plane, he dripped and poured enamel paints on canvases and papers, a method that more precisely controlled the application of line. His preference for the technique of fluid paint spilling from the can or drizzling from the tips of sticks or trowels was heralded by critic Harold Rosenberg as “action painting.” These unconventional working methods and his own physical presence while creating these works have assumed epic proportions. In the last four years of his life – he died in an automobile accident on August 11, 1956 – he produced significantly fewer works, with each further refining his pouring method. Compositionally, they hark back to his earlier style through the reintroduction of figurative elements as in Ocean Greyness, which also addresses his allover abstract technique. Its dramatic, swirling forms set against a dark ground recall Pollock’s Eyes in the Heat (1946).

Text from the Guggenheim website

Emilio Vedova (Italian, 1919-2006)

Image of Time (Barrier)

1951

Egg tempera on canvas

51 3/8 x 67 1/8 inches (130.5 x 170.4cm)

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© Emilio Vedova

Emilio Vedova produced art in response to contemporary social upheavals, however his political position was contrary to that of his early modern counterparts, the Italian Futurists, who coalesced as a group in the years preceding World War I. While the Futurists romantically celebrated the aggressive energies inherent in societal conflict and technological advancement, Vedova’s feverish, violent canvases convey – in abstract terms – his horror and moral protestation in the face of man’s assault on his own kind.

Vedova expressed a political consciousness in his work for the first time during the late 1930s, when his works were inspired by the Spanish Civil War. His continuing commitment to social issues gave rise to series such as Cycle of Protest (Ciclo della protesta, 1956) and Image of Time (Immagine del tempo, 1946-1959). Although the motivation behind Image of Time (Barrier) (Sbarramento) is political, its formal preoccupations parallel those of the American Abstract Expressionists, namely Franz Kline. The drama of the angular, graphic slashes of black on white is heightened with accents of orange-red. Occupying a shallow space, pictorial elements are locked together in formal combat and emotional turmoil.

Text from the Guggenheim website

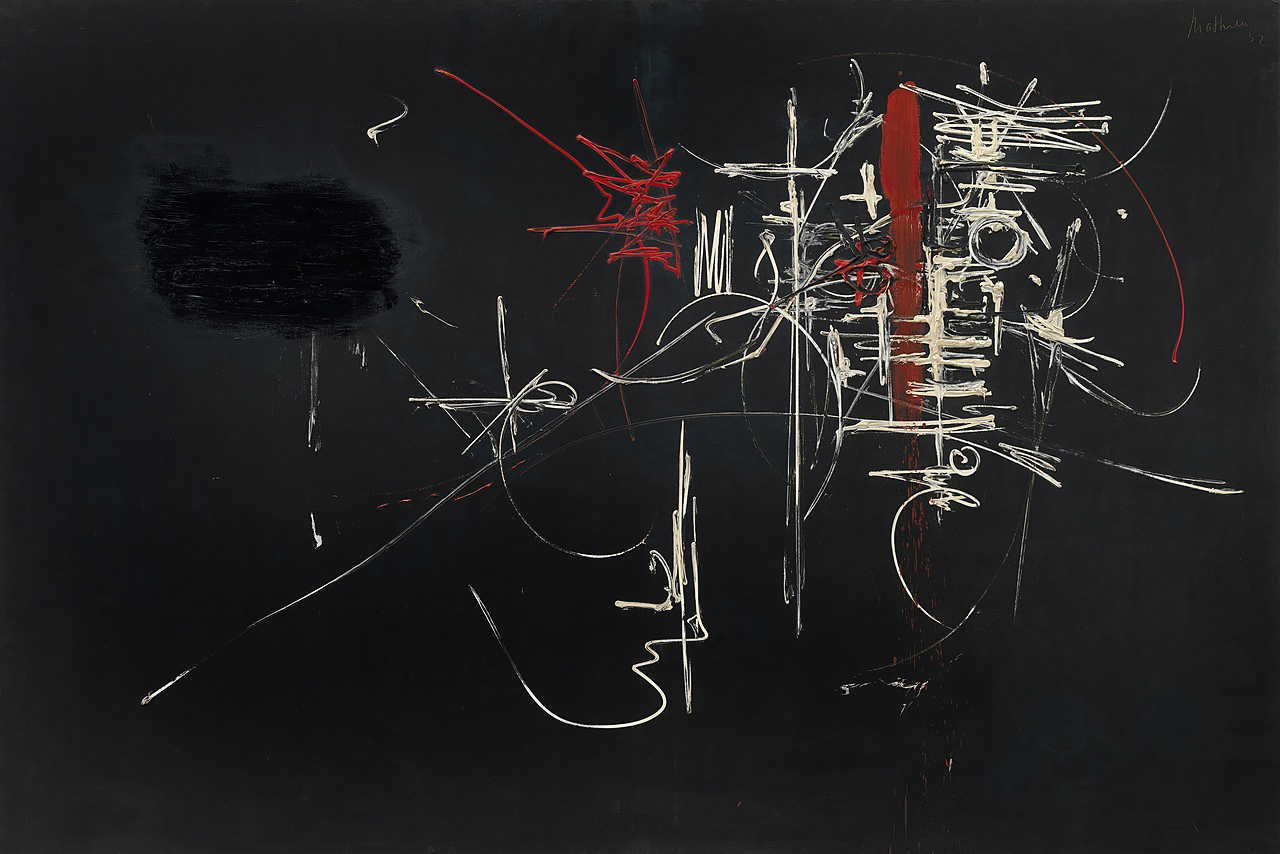

Georges Mathieu (French, 1921-2012)

Painting

1952

Oil on canvas

78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 299.7cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

A key figure of the postwar art scene in Paris as well as a champion – and competitor – of the burgeoning movement of Abstract Expressionist painters in New York, Georges Mathieu practiced a mode of gestural abstraction that was decidedly calligraphic. His paintings were executed with controlled force, resulting in a matrix of lines bursting from a single point and thrusting outward in every direction, as seen in Painting (Peinture, 1952). The artist often squeezed paint directly from tubes onto the canvas and emphasised the necessity of rapid application in order to harness an intuitive expression. Mathieu also occasionally introduced a performative dimension to his painting in the 1950s, executing large canvases before audiences. This merger of painting and performance anticipated the work of Yves Klein and others in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Text from the Guggenheim website

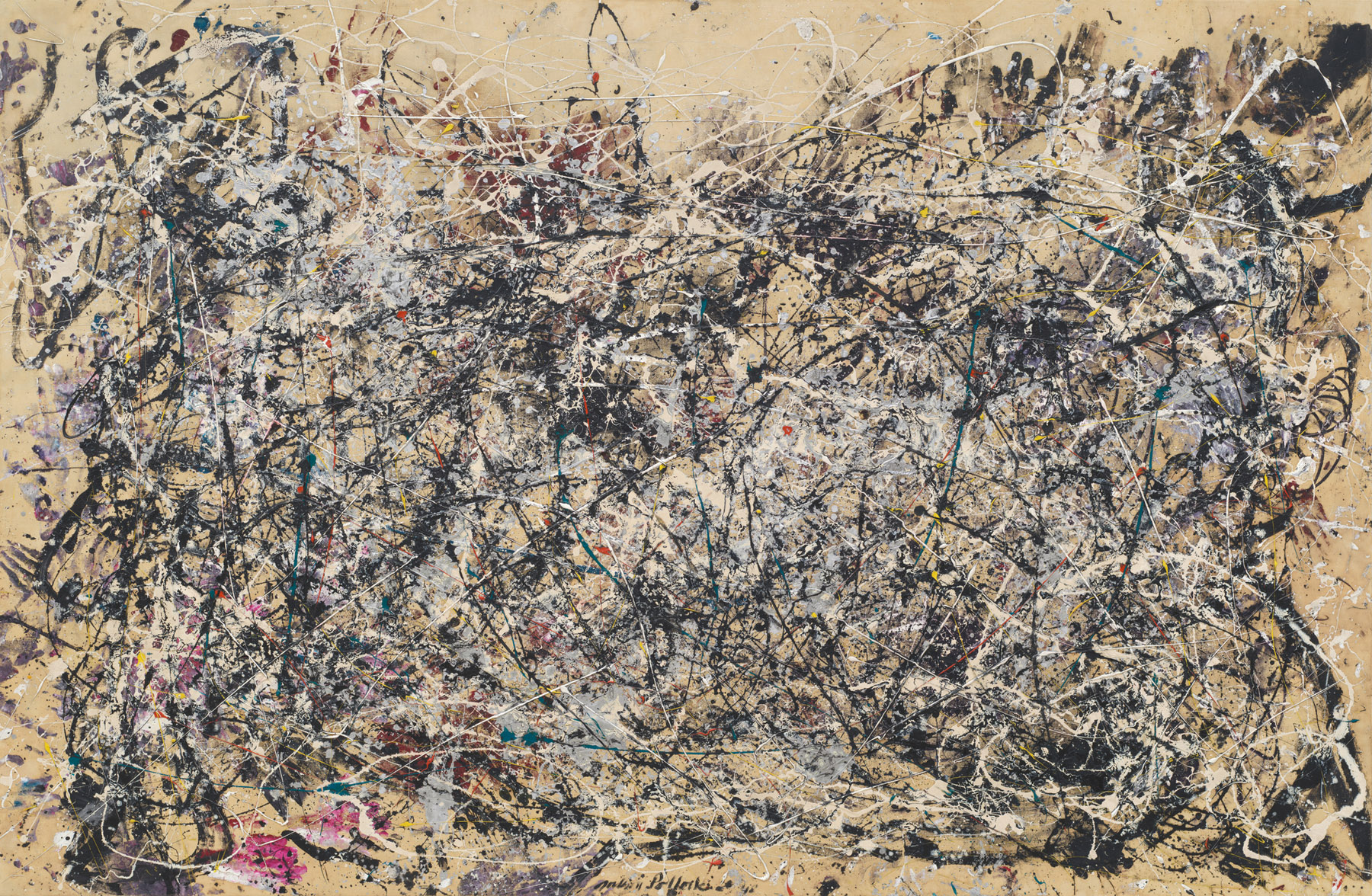

Jackson Pollock (American, 1912-1956)

Ocean Greyness

1953

Oil on canvas

57 3/4 x 90 1/8 inches (146.7 x 229cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© 2016 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The critical debate that surrounded Abstract Expressionism during the late 1940s was embodied in the work of Jackson Pollock. Clement Greenberg, a leading critic and Pollock’s champion, professed that each discrete art form should, above all else, aspire to a demonstration of its own intrinsic properties and not encroach on the domains of other art forms. A successful painting, he believed, affirmed its inherent two-dimensionality and aimed toward complete abstraction. At the same time, however, the critic Harold Rosenberg was extolling the subjective quality of art; fervent brushstrokes were construed as expressions of an artist’s inner self, and the abstract canvas became a gestural theater of private passions. Pollock’s art – from the early, Surrealist-inspired figurative canvases and those invoking “primitive” archetypes to the later labyrinthine webs of poured paint – elicited both readings. Pollock’s reluctance to discuss his subject matter and his emphasis on the immediacy of the visual image contributed to shifting and, ultimately, dialectic views of his work.

In 1951, at the height of the artist’s career, Vogue magazine published fashion photographs by Cecil Beaton of models posing in front of Pollock’s drip paintings. Although this commercial recognition signalled public acceptance – and was symptomatic of mass culture’s inevitable expropriation of the avant-garde – Pollock continuously questioned the direction and reception of his art. His ambivalence about abstract painting, marked by a fear of being considered merely a “decorative” artist, was exacerbated, and it was around this time that he reintroduced to his paintings the quasi-figurative elements that he had abandoned when concentrating on the poured canvases. Ocean Greyness, one of Pollock’s last great works, depicts several disembodied eyes hidden within the swirling coloured fragments that materialise from the dense, scumbled gray ground. “When you are painting out of your unconscious,” he claimed, “figures are bound to emerge.” Manifest in this painting is a dynamic tension between representation and abstraction that, finally, constitutes the core of Pollock’s multileveled oeuvre.

Nancy Spector

Text from the Guggenheim website

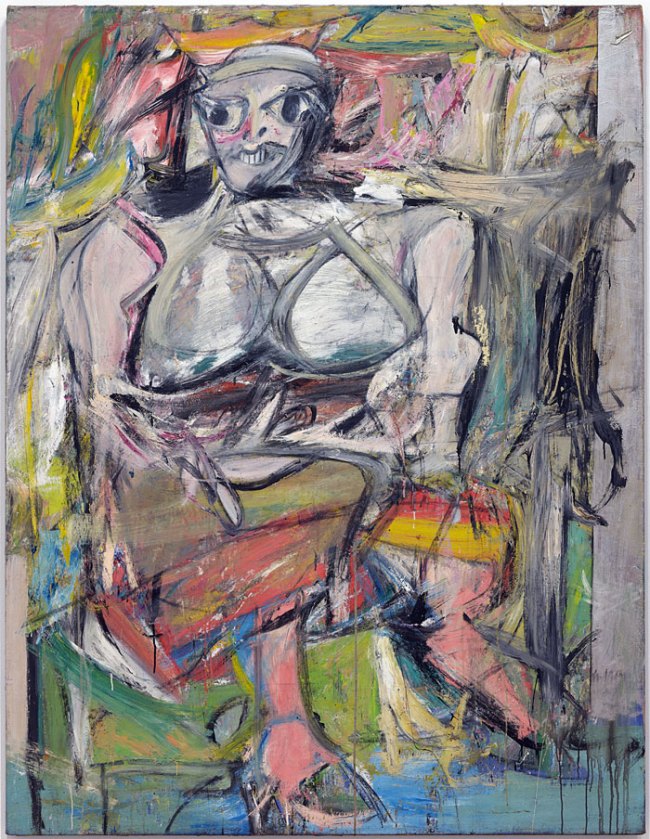

Willem de Kooning (American, 1904-1997)

Composition

1955

Oil, enamel, and charcoal on canvas

201 x 175.6cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© 2012 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Although often cited as the originator of Action Painting, an abstract, purely formal and intuitive means of expression, Willem de Kooning most often worked from observable reality, primarily from figures and the landscape. From 1950 to 1955, de Kooning completed his famous Women series, integrating the human form with the aggressive paint application, bold colours, and sweeping strokes of Abstract Expressionism. These female “portraits” provoked not only with their vulgar carnality and garish colours, but also because of their embrace of figural representation, a choice deemed regressive by many of de Kooning’s Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, but one to which he consistently returned for many decades.

Composition serves as a bridge between the Women and de Kooning’s next series of work, classified by critic Thomas Hess as the Abstract Urban Landscapes (1955-1958). According to the artist, “the landscape is in the Woman and there is Woman in the landscapes.” Indeed, Composition reads as a Woman obfuscated by de Kooning’s agitated brushwork, clashing colours, and allover composition with no fixed viewpoint. Completed while the artist had a studio in downtown New York, Composition’s energised dashes of red, turquoise, and chrome yellow suggest the frenetic pace of city life, without representing any identifiable urban inhabitants or forms.

Painted 20 years later, after de Kooning moved to East Hampton, New York, seeking to work in greater peace and isolation, … Whose Name Was Writ in Water takes nature as its theme. Water was a favourite subject of the artist, and he devised a rapid, slippery technique of broad impasto strokes with frayed edges, speckled with drips, to convey its fluidity and breaking movement. The title, taken from an epigraph on Keats’s tomb, which de Kooning had seen on a trip to Rome in 1960, is, according to critic Harold Rosenberg, “the closest de Kooning can come to saluting overtly the impermanence of existence, and things in a state of disappearance.” Always aiming to reinforce the content of his work with his technique, de Kooning reworked his canvases over and over again, making each painting a composite of evanescent visual traces. The scrambled pictorial vocabulary and condensed space of the urban landscapes was gradually diffused in de Kooning’s later work. More open compositions, a less cluttered palette, and looser, liquid brushstrokes reveal a painter relieved of the nervous, claustrophobic atmosphere of city life and newly at peace with his rural surroundings.

Bridget Alsdorf

Text from the Guggenheim website

Pierre Alechinsky (Belgium, b. 1927)

Vanish

1959

Oil on canvas

78 3/4 x 110 1/4 inches (200 x 280cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, Julian and Jean Aberbach, 1967

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Pierre Alechinsky was a central figure in Cobra, a European artists’ group that emphasised material and its spontaneous application. The abstract and concrete often merge in his work; in Vanish (Disparaître, 1959), Alechinsky focused on the appearance and disappearance of a female figure in the centre of the canvas. This emergent shape and the background coalesce into a vigorously brushed surface that is distinguished by thickly impastoed white pigment and a network of predominantly blue lines. There are still traces of the allover patterning that characterises the artist’s watercolours and earlier canvases such as The Ant Hill (La fourmilière, 1954). His work likewise exhibits a fluidity and vitality that points to the artist’s fascination with Japanese calligraphy, which he observed during his travels to Japan in 1955.

Text from the Guggenheim website

Jean Dubuffet (French, 1901-1985)

The Substance of Stars

December 1959

Metal foil on Masonite

59 x 76 3/4 inches (150 x 195cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

© 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

In Jean Dubuffet’s Matériologies series (1959-1960), of which The Substance of Stars (Substance d’astre, December 1959) is an example, form is subverted by an emphasis on materials, meant to stimulate mental responses and associations in the viewer. Far from being an abstraction in the usual sense, this and other such works suggest concern with topographical reality – the earth, water and sky, and the stars. These elements are not conveyed through descriptive images or through the use of materials identical with a natural substance, but through evocative effects of their artificial counterparts, here black, gray, and silver metal foil. Nature, although closely observed, is thus rendered through artifice, and reality conjured up through elaborate illusion.

Text from the Guggenheim website

Karel Appel

(Dutch, 1921-2006)

The Crying Crocodile Tries to Catch the Sun

1956

Oil on canvas

145.5 x 113.1cm

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice, 1976

© 2012 Karel Appel Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Karel Appel, like Asger Jorn, was a member of the Cobra group, which emphasised material and its spontaneous application. Although the group was short-lived, its concerns have endured in his work. The single standing figures of humans or animals he developed during the 1950s are rendered in a deliberately awkward, naive way, with no attempt at modelling or perspectival illusionism. Thus, the crocodile in this painting is presented as a flat and immobile form, contoured with heavy black lines in the manner of a child’s drawing.

Appel’s paint handling activates a frenzy of rhythmic movement in The Crying Crocodile Tries to Catch the Sun (1956), despite the static monumentality of the subject. Drips and smears are interspersed with veritable stalactites of brilliant, unmodulated colour that buckle, ooze, slash, wither, and thread their way over the surface. The physicality of the impasto and its topographic variety allow it to reflect light and cast shadows dramatically, increasing the emotional intensity of violent colour contrasts. In 1956 Appel summarised the genesis of his work: “I never try to make a painting; it is a howl, it is naked, it is like a child, it is a caged tiger… My tube is like a rocket writing its own space.”1

Lucy Flint

1/ Karel Appel, quoted in Alfred Frankenstein, ed., Karel Appel (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1980), p. 52.

Text from the Guggenheim website

Asger Jorn (Danish, 1914-1973)

A Soul for Sale (Ausverkauf einer Seele)

1958-1959

Oil with sand on canvas

200 x 250cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Purchased with funds contributed by the Evelyn Sharp Foundation, 1983

© 2012 Donation Jorn, Silkeborg / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/COPY-DAN, Copenhagen

Asger Jorn’s career began in 1936 when he ventured from Copenhagen to Paris with the goal of apprenticing under the legendary painter Vasily Kandinsky. On his arrival, however, Jorn promptly learned that Kandinsky did not operate his own academy. Instead, the young artist enrolled in Fernand Léger’s Académie contemporaine and worked with Le Corbusier on his Pavillon des temps nouveaux at the World Exhibition of 1937, experiencing firsthand the formal restraint and balance that characterised the art and architecture of Le Corbusier’s Purism – a movement dedicated to highly rationalised geometric forms.

But Jorn preferred methods rooted in spontaneity and would ultimately reject the techniques of his teachers in favour of a life of art, writing, and activism that amounted to an assault on rationality in all its guises – painterly, architectural, and social. In 1948 Jorn and others, including Karel Appel, founded Cobra, an international collection of like-minded experimental artists. Indebted to the style of Jorn’s friend Jean Dubuffet – whose Art Brut looked to traditions of art making commonly considered debased or vulgar by the art establishment – Cobra art combined Surrealist automatism with the materiality of gestural mark making. Many of Jorn’s early paintings exist on the boundary between abstraction and figuration, aligning his practice with that of American contemporaries including Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock.

In 1957 Jorn merged his anti-Bauhaus group, the Mouvement internationale pour un Bauhaus imaginiste (International movement for an imaginist Bauhaus, founded in 1954), with Guy Debord’s Lettrist International, to form the Internationale Situationiste (Situationist International, SI), a Marxist, activist group of writers, artists, and theorists who sought to destabilise societal practices and structures ranging from urban planning to the art establishment. Jorn continued to exhibit an anarchic spirit even after he left the SI in 1961. As an act of rebellion against the concept of art prizes, for instance, he refused to accept the Guggenheim Museum’s 1964 International Award for his painting Dead Drunk Danes (Døddrukne Danskere, 1960), stating in a telegram that he wanted no part of the museum’s “ridiculous game.”

During his SI period Jorn focused great effort on a series of “modification” paintings, which utilised other paintings as pre-existing supports on which to produce new images or marks, but he also continued to work within his Cobra aesthetic, making paintings such as A Soul for Sale (Ausverkauf einer Seele, 1958-59). In both its use of expressive brushwork and its collapsing of foreground and background, figuration and abstraction, A Soul for Sale articulates some of Jorn’s most significant interrogations of the precepts of geometric abstraction and rationalised art making. Barely discernible amid a field of gestural marks, the work’s central figure – demarcated by fragmented contour lines that seem to merge with the abstract ground even as they define the figure’s form – appears on the verge of disappearing. Jorn seems to deny his subject even as he represents it. In a similar fashion, rational strategies of delineating form or representing depth, seen in the contour drawing or in the crosshatching at the top right of the painting, are overcome by strikingly crude or naive methods of mark making, such as scattered soil or paint smudges – techniques Jorn first developed early on as a Cobra artist.

Text from the Guggenheim website

Yves Klein (French, 1928-1962)

Large Blue Anthropometry (ANT 105) [La Grande Anthropométrie Bleue (ANT 105)]

c. 1960

Blue pigment and synthetic resin on paper on canvas

280 x 428cm

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao

Yves Klein’s first passion in life was judo. In 1952 he moved to Tokyo and studied at the Ko-do-kan Judo Institute, where he earned a black belt. When he returned to Paris in 1955 and discovered to his dismay that the Fédération Française de Judo did not extol him as a star, he shifted his attentions and pursued a secondary interest – a career in the arts. During the ensuing seven years Klein assembled a multifarious and critically complex body of work ranging from monochrome canvases and wall reliefs to paintings made with fire. He is renowned for his almost exclusive use of a strikingly resonant, powdery ultramarine pigment, which he patented under the name “International Klein Blue,” claiming that it represented the physical manifestation of cosmic energy that, otherwise invisible, floats freely in the air. In addition to monochrome paintings, Klein applied this pigment to sponges, which he attached to canvases as relief elements or positioned on wire stands to create biomorphic or anthropomorphic sculptures. First exhibited in Paris in 1959, the sponge sculptures – all essentially alike, yet ultimately all different – formed a forest of discrete objects surrounding the gallery visitors. About these works Klein explained, “Thanks to the sponges – raw living matter – I was going to be able to make portraits of the observers of my monochromes, who … after having voyaged in the blue of my pictures, return totally impregnated in sensibility, as are the sponges.”1

For his Anthropométries series, Klein famously used nude female models drenched in paint as “brushes.” His system of pressing bodies against the paper support (which was later mounted on canvas) rejected any illusion of a third dimension in the pictorial space. In these works, the subject, object, and medium become confused with one another to produce a trace of the body’s presence. Klein’s unconventional activities also included releasing thousands of blue balloons into the sky, and exhibiting an empty, white-walled room and then selling portions of the interior air, which he called “zones” of “immaterial pictorial sensibility.” His intentions remain perplexing thirty years after his sudden death. Whether Klein truly believed in the mystical capacity of the artist to capture cosmic particles in paint and to create aesthetic experiences out of thin air and then apportion them at whim is difficult to determine. The argument has also been made that he was essentially a parodist who mocked the metaphysical inclinations of many modern painters, while making a travesty of the art market.

Nancy Spector

1/ Yves Klein, “Remarques sur quelques oeuvres exposées chez Colette ‘Allendy’,” 1958, Klein archive, quoted in Nan Rosenthal, “Assisted Levitation: The Art of Yves Klein,” in Yves Klein 1928-1962: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (Houston: Institute for the Arts, Rice University, 1982), p. 111.

Text from the Guggenheim website

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

1071 5th Avenue (at 89th Street)

New York

Opening hours:

Sunday – Monday, 11am – 6pm

Wednesday – Friday 11am – 6pm

Saturday 11am – 8pm

Closed Tuesday

![Takeo Yamaguchi

(Japanese, 1902-1983)

'Work – Yellow (Unstable Square [Fuantei shikaku])' 1958

Takeo Yamaguchi

(Japanese, 1902-1983)

'Work – Yellow (Unstable Square [Fuantei shikaku])' 1958](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/takeo-yamaguchi-web.jpg?w=650&h=646)

![Yves Klein (French, 1928-1962) 'Large Blue Anthropometry (ANT 105) [La Grande Anthropométrie Bleue (ANT 105)]' c. 1960 Yves Klein (French, 1928-1962) 'Large Blue Anthropometry (ANT 105) [La Grande Anthropométrie Bleue (ANT 105)]' c. 1960](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/klein-large-blue.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.