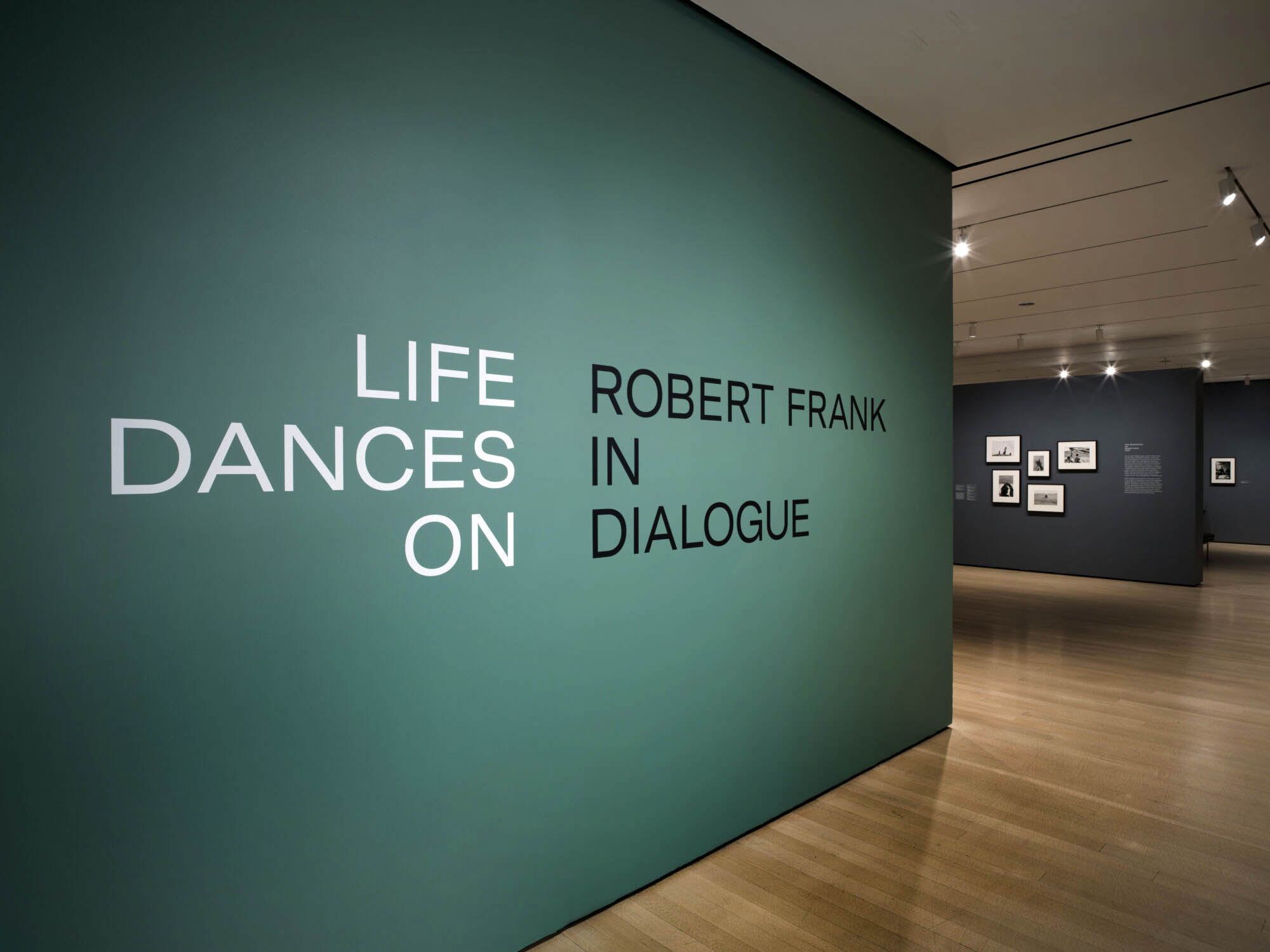

Exhibition dates: 15th September, 2024 – 11th January, 2025

Curator: Organised by Lucy Gallun, Curator, with Kaitlin Booher, Newhall Fellow, and Casey Li, 12 Month Intern, Department of Photography.

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

From the Bus, New York

1958

Gelatin silver print

13 15/16 × 13 1/4″ (35.4 × 33.7cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Robert Frank Collection, Robert B. Menschel Fund

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

The first posting on a new year…

In front of me I have the sea

While the photographs from his groundbreaking photobook The Americans (1958) have defined the artistic reputation and legacy of Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank and his influence on a later generation of documentary photographers, I am so grateful to the man for not retreating into his shell as so many artists do, finding a style which makes them famous and makes them money and then repeating the formula over and over again ad nauseam.

Frank was ever creative, always exploring new ways of filmic and photographic expression. I admire that. While “his perpetual experimentation and collaborations across various mediums” did not produce another seminal body of work – indeed Arthur Lubow has argued that if the aim of this exhibition is to reposition Frank’s reputation through showcasing six decades of later work the problem being that his genius as a photographer did not carry over into filmmaking1 – no matter!

Frank was not afraid to put himself out there as an artist, challenging himself to see differently, to develop further as an artist and as a human being. As he said, “I think of myself, standing in a world that is never standing still … I’m still in there fighting, alive because I believe in what I’m trying to do now.”

Critical to his new way of seeing after The Americans was Frank’s move beyond a single, static image into combining multiple negatives, images, text together. Recently I again delved through my copy of Frank’s 1972 photobook The Lines of My Hand, which “demonstrates Frank’s particular interest in the visual effects and meaning produced from combinations of images, either within a single photograph or formed by printing multiple negatives together to create a dense montage.” (Text from MoMA)

What’s so striking about the photobook is its tightly packed nature, its pages filled with ideas and images. Frank was using his intuition to construct a new language of photography: multiple, diverse and overlaid perspectives complicit with narratives not external to the self but an internal vision of a felt reality, visions that exist somewhere between documentary and fiction.

Here is abstraction and isolation, loneliness in the dream… the white line eternally disappearing into the distance in 34th Street (1949); tickertape floating in the air in Wall Street (1951); stiff men in bowler hats in City of London (1951) and the lines of the hand in Untitled [The Lines of the Hand] (Paris, 1949-1951, below) with the declaration ‘Sciences and Mysteries’. Sciences and mysteries, realities and abstractions, the known and unknown. The Lines of My Hand are the song lines of Frank’s life, the photographs breathing into existence his innermost thoughts and truths. Who am I? What do I believe in?

“Outside it is snowing, no waves at all. The beach is white, the fence posts are grey. I am looking back into a world gone forever. Thinking of a time that will never return. A book of photographs is looking at me. Twenty-five years of looking for the right road. Post cards from everywhere. If there are any answers I have lost them.” (Opening words from The Lines of My Hand)

“Frank felt trapped by the expectations and pigeonholing that the lionization of “The Americans” induced, and he recoiled in horror at the prospect of repeating himself. Beyond that, he gave various explanations over the years for why he abandoned the 35 mm camera that he brandished like a sorcerer’s wand. He explained that he had lost faith in the capacity of a single photograph to convey the truth. And his search had turned inward. “The truth is the way to reveal something about your life, your thoughts, where you stand,” he said.”2 This turning inwards was facilitated by his move in 1970 with his wife June Leaf to the rural town of Mabou on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada: “what I wanted to photograph was not really what was in front of my eyes but what was inside.”

Personally I don’t think it matters that the later photographs are not as memorable as those in The Americans. What matters is that Frank believed in what he was doing: it was his truth telling. “I am no longer the solitary observer turning away after the click of the shutter,” Frank declared. “Instead I’m trying to recapture what I saw, what I heard and what I feel. What I know!”

Finally, in the film Life Dances On (1980), his wife looks at the camera and asks Frank, “Why do you make these pictures?” In an introduction to the film’s screening, he answered: “Because I am alive.”

Because in front of him he had the sea…

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Arthur Lubow. “‘The Americans’ Made the Photographer Robert Frank a Star. What Came Next?” on The New York Times website Sept. 12, 2024 [Online] Cited 15/12/2024

2/ Ibid.,

Many thanks to MoMA for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Untitled [The Lines of the Hand]

Paris, 1949-1951

Gelatin silver print

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

This photograph as far as I know is not in the exhibition. It is used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research.

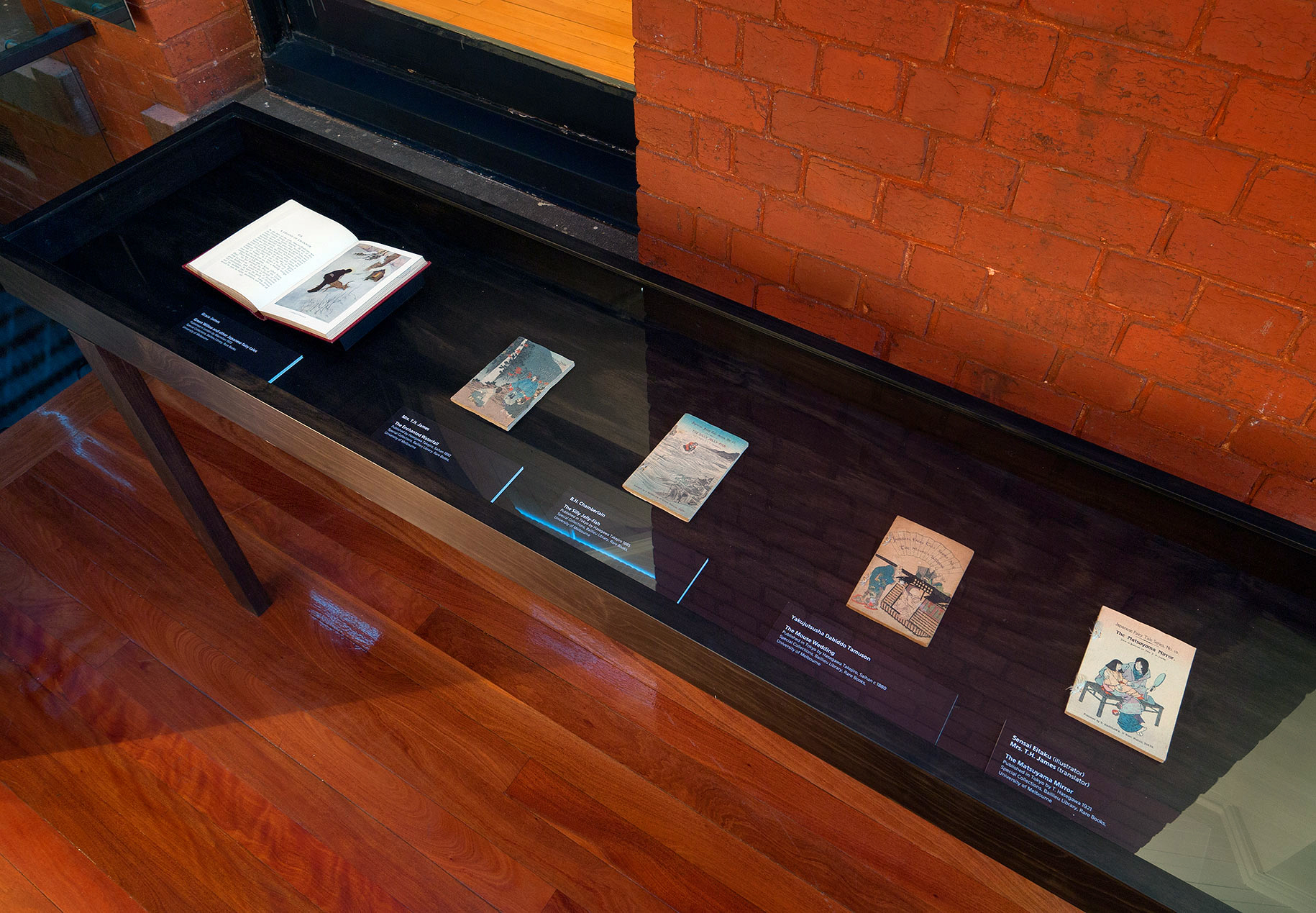

Installation views, Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, from September 15, 2024, through January 11, 2025

Photos: Jonathan Dorado

© 2024 The Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Museum of Modern Art announces Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue, an exhibition that will provide new insights into the interdisciplinary and lesser-known aspects of photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank’s expansive career. The exhibition will delve into the six decades that followed Frank’s landmark photobook The Americans (1958) until his death in 2019, highlighting his perpetual experimentation and collaborations across various mediums. Coinciding with the centennial of his birth and taking its name from the artist’s 1980 film, Life Dances On will explore Frank’s artistic and personal dialogues with other artists and with his communities. The exhibition will feature more than 200 objects, including photographs, films, books, and archival materials, drawn from MoMA’s extensive collection alongside significant loans.

Text from the MoMA website

Unknown photographer

Robert Frank, shown from behind, making “Pull My Daisy”

1959

John Cohen/John Cohen Irrevocable Trust, via The Museum of Modern Art, NY

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Pull My Daisy

1959

Robert Frank/The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation, via the Museum of Modern Art

Pull My Daisy incorporated improvisation by actors, artists and poets.

“I think of myself, standing in a world that is never standing still,” the artist Robert Frank once wrote. “I’m still in there fighting, alive because I believe in what I’m trying to do now.” Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue – the artist’s first solo exhibition at MoMA – provides a new perspective on his expansive body of work by exploring the six vibrant decades of Frank’s career following the 1958 publication of his landmark photobook, The Americans.

Coinciding with the centennial of Frank’s birth, the exhibition will explore his restless experimentation across mediums including photography, film, and books, as well as his dialogues with other artists and his communities. It will include some 200 works made over 60 years until the artist’s death in 2019, many drawn from MoMA’s extensive collection, as well as materials that have never before been exhibited.

The exhibition borrows its title from Frank’s poignant 1980 film, in which the artist reflects on the individuals who have shaped his outlook. Like much of his work, the film is set in New York City and Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where he and his wife, the artist June Leaf, moved in 1970. In the film, Leaf looks at the camera and asks Frank, “Why do you make these pictures?” In an introduction to the film’s screening, he answered: “Because I am alive.”

Text from the MoMA website

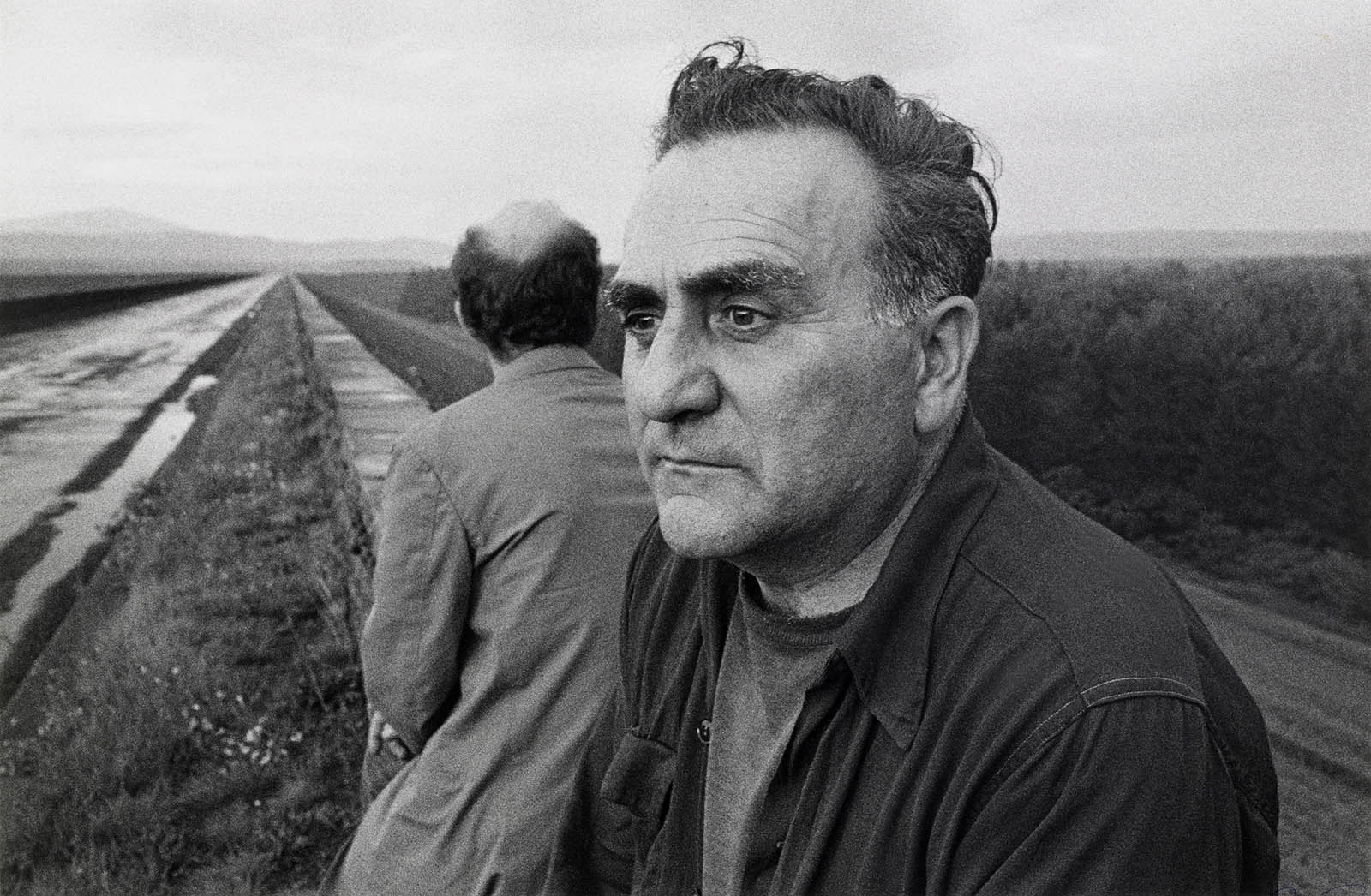

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Jack Kerouac

1959

Gelatin silver print

10 7/8 x 8 5/16 inches (27.7 x 21.1cm)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

Robert Frank Collection, Gift of Robert Frank

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Marvin Israel and Raoul Hague, Woodstock, New York

1962

Gelatin silver print

11 1/8 × 16 7/8 inches (28.3 × 42.8cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of the artist

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

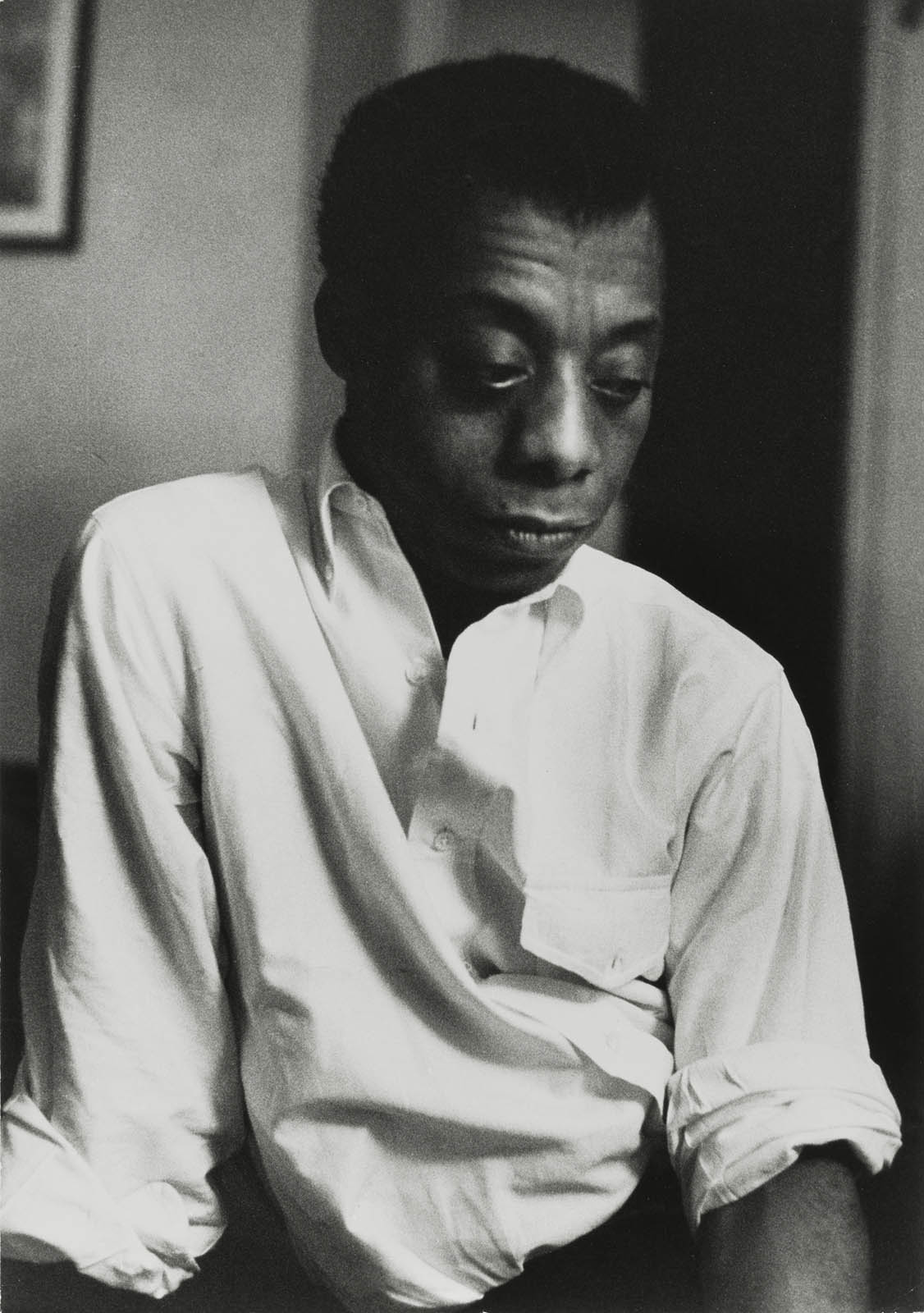

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

James Baldwin

c. 1963

Gelatin silver print

13 15/16 × 9 13/16 inches (35.4 × 24.9cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of the artist

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

The Museum of Modern Art presents Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue, an exhibition that provides new insights into the interdisciplinary and lesser-known aspects of photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank’s expansive career. On view from September 15, 2024, to January 11, 2025, the exhibition delves into the six decades that followed Frank’s landmark photobook The Americans (1958) until his death in 2019, highlighting his perpetual experimentation and collaborations across various mediums. Coinciding with the centennial of the artist’s birth, and taking its name from his 1980 film, Life Dances On explores Frank’s artistic and personal dialogues with other artists and with his communities. The exhibition features more than 250 objects, including photographs, films, books, and archival materials, drawn from MoMA’s extensive collection alongside significant loans. Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue is organised by Lucy Gallun, Curator, with Kaitlin Booher, Newhall Fellow, and Casey Li, 12 Month Intern, Department of Photography.

“This exhibition offers visitors a fresh perspective on this beloved and influential artist,” said Gallun. “The enormous impact of Frank’s book The Americans meant that he is often remembered as a solo photographer on a road trip, a Swiss artist making pictures of an America that he traversed as an outsider. And yet, in the six decades that followed, Frank continually forged new paths in his work, often in direct artistic conversation with others, and these contributions warrant closer attention. The pictures, films, and books he made in these years are evidence of Frank’s ceaseless creative exploration and observation of life, at once searing and tender.”

Organised loosely chronologically, Life Dances On focuses on the theme of dialogue in Frank’s work and reflects on the significance of individuals who shaped his outlook. Frank’s own words are present throughout the exhibition – in the texts he scrawled directly onto his photographic negatives, in the spoken narrative accompanying his films, and in quotes woven into the exhibition catalogue published by MoMA in conjunction with the exhibition. Also revealed throughout the exhibition is Frank’s innovation across multiple mediums, from his first forays into filmmaking alongside other Beat Generation artists, with films such as Pull My Daisy (1959), to the artist’s books he called “visual diaries,” which he produced almost yearly over the last decade of his life.

By focusing on dialogue and experimentation, the exhibition explores such enduring subjects as artistic inspiration, family, partnership, loss, and memory through the lens of Frank’s own personal traumas and life experiences. Among the works presented in the exhibition is a selection of photographs drawn from Frank’s footage for his 1980 film Life Dances On. These works reflect on the significance of individuals who shaped Frank’s own outlook – in this case, his daughter Andrea and his friend and film collaborator Danny Seymour. Like much of his work, the film finds its setting in Frank’s own communities in New York City and in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, where he and his wife, the artist June Leaf, moved in 1970. An abundance of material was loaned to the exhibition by the June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation, including works from the artist’s archives that are shown publicly for the first time, as well as personal artefacts, correspondence, and book maquettes. …

MoMA has been exhibiting Frank’s work since 1950, early in his career. In 1962, the Museum featured Frank’s work in a two-person exhibition alongside photographer Harry Callahan. Since then, the Museum has regularly collected and exhibited his work, and today the Museum’s collection includes over 200 of Frank’s photographs. That collection has been built through important gifts from Robert and Gayle Greenhill in 2013, and more recently, a promised gift to the Museum from Michael Jesselson, comprising a remarkable group of works, many of which are presented at MoMA for the first time in this exhibition. In 2015, the artist made an extraordinary gift of his complete film and video works, spanning the entirety of his career in filmmaking. MoMA’s Department of Film has since been engaged in a multiyear restoration project of these materials. Building upon this significant history with the Museum, Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue is the first solo exhibition of Robert Frank’s work at MoMA.

Publication

The accompanying publication, edited by Gallun, features photographs, films, books, and archival materials, layered with quotes from Frank on his influences and process. Three scholarly essays, excerpts from previously unpublished video footage, and a rich visual chronology together explore Frank’s ceaseless creative exploration and observation of life. 192 pages, 150 illustrations. Hardcover, $60. ISBN: 978-1-63345-164-3. Published by The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Press release from MoMA

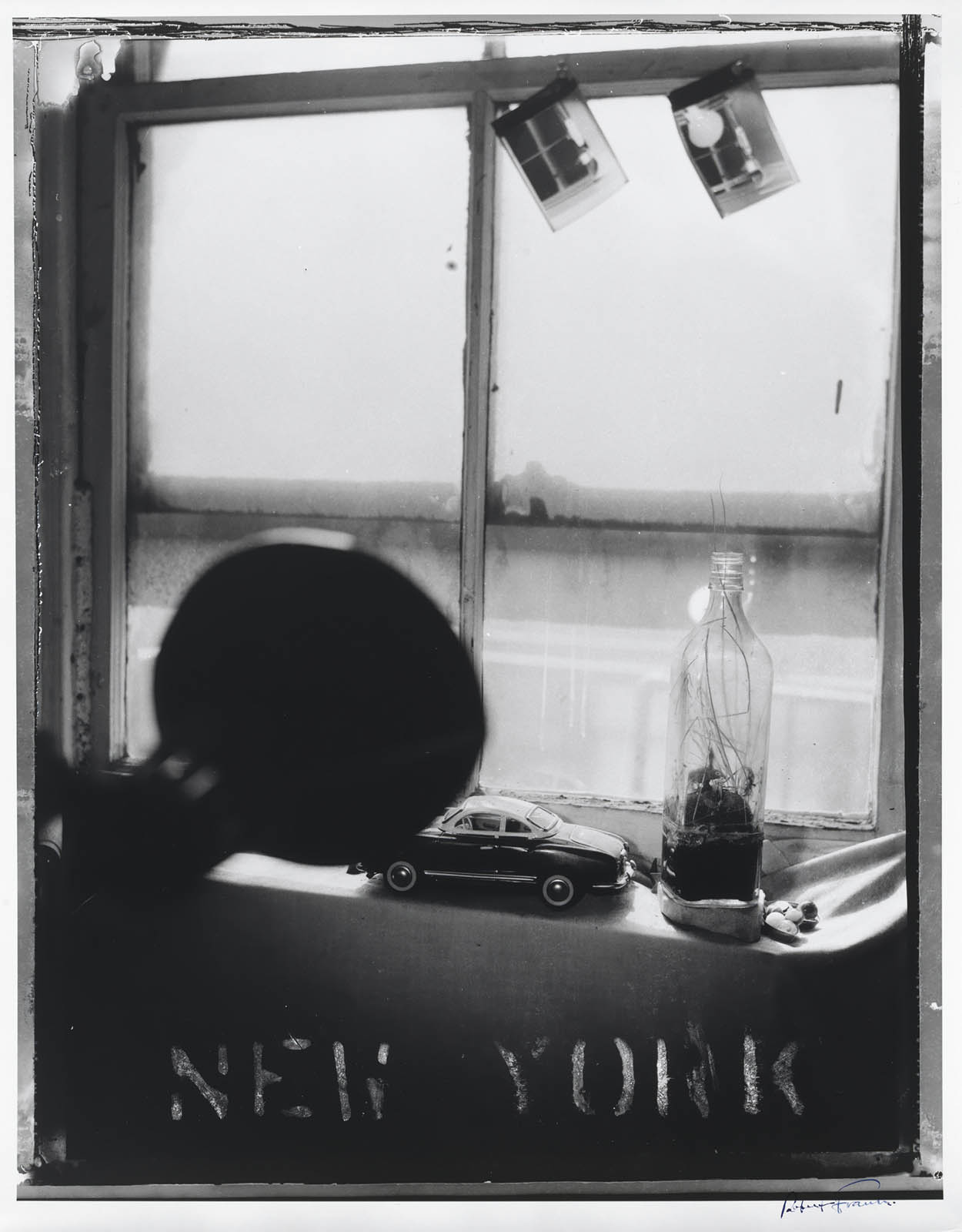

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Beauty Contest, Chinatown

c. 1968

Robert Frank/The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation, via The Museum of Modern Art, NY

Frank collaged multiple prints of news photographers to convey a sense of the frenzy.

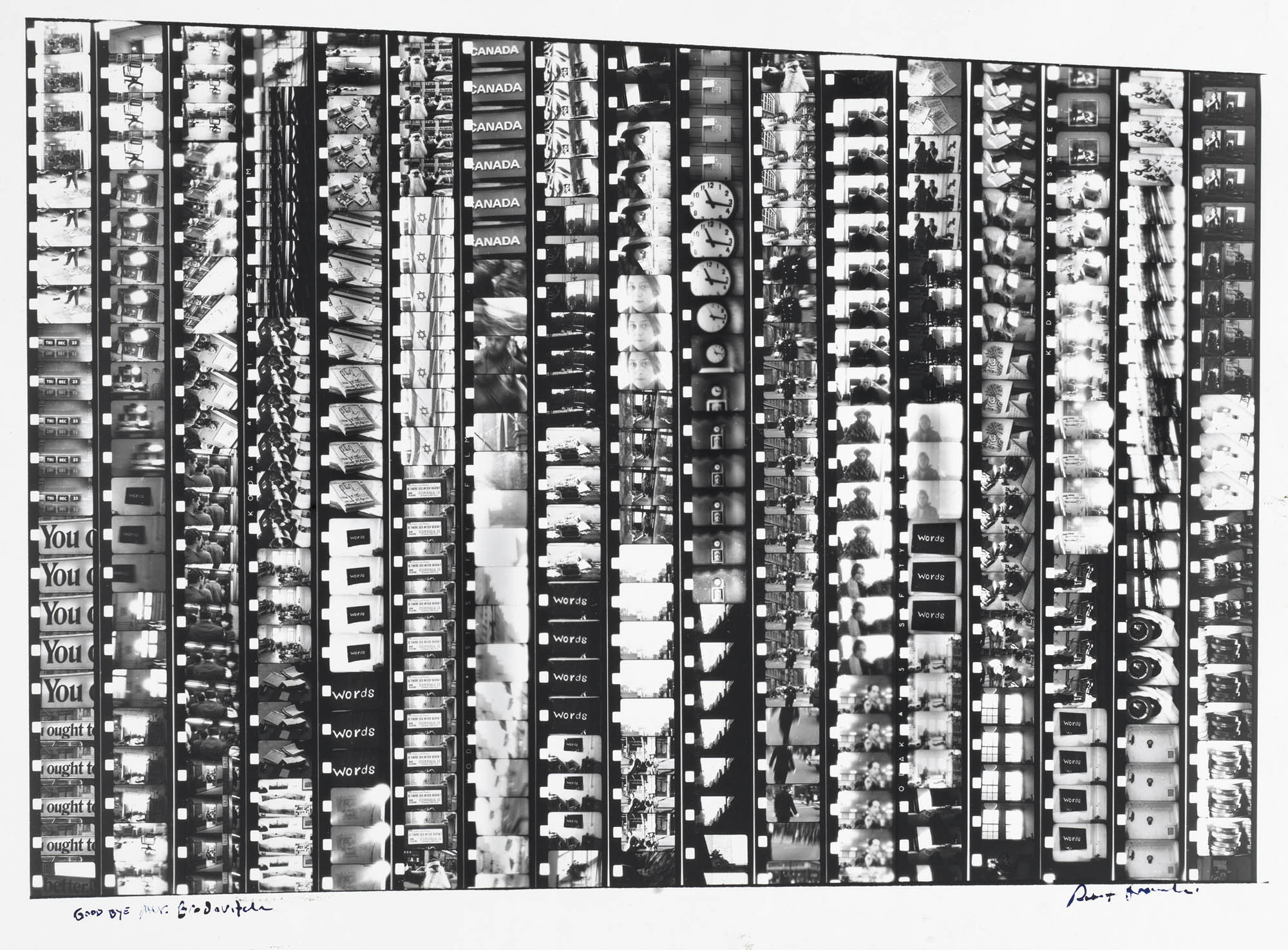

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Goodbye Mr. Brodovitch – I Am Leaving New York

1971

Gelatin silver print

15 7/8 × 19 15/16 inches (40.3 × 50.6cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Promised gift of Michael Jesselson

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Untitled (bulletin board)

1971

Gelatin silver print

8 7/8 × 13 1/8 inches (22.6 × 33.4cm)

The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

When Frank was moving to Nova Scotia, Frank photographed a bulletin board in his East Village loft, making one picture out of many.

The Beginning of Something New

The summer of 1958 marked a shift in Frank’s work. He had already finalised the selection of pictures that would appear in his photobook The Americans. For a new series, Frank photographed passersby from the window of a New York bus as it traversed Fifth Avenue. The pictures – a sequence of frames that appear linked by his own movement – indicated a notable moment of change beyond a single, static image. In 1972 he reflected on their significance: “When I selected the pictures and put them together I knew and I felt that I had come to the end of a chapter. And in it was the beginning of something new.”

Frank was also on the lookout for cinematic scenes. On the night of Independence Day, he photographed revelers sleeping on the beach among the holiday detritus. The stillness of the nighttime images contrasts with the daylit beach scenes he captured of his family on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, where Frank also shot his first film that same summer. Although it would remain unfinished, the film anticipated the collaborative and experimental spirit of his work to come.

The Way These Painters Lived

From his window across a courtyard, Frank could watch the painter Willem de Kooning as he paced in his studio and contemplated his canvas. “I think that the people that influenced me most were the abstractionist painters I met; and what influenced me strongly was the way these painters lived,” Frank said of his time embedded in New York City’s vibrant arts community. “They were people who really believed in what they did. So it reinforced my belief that you could really follow your intuition. … You could photograph what you felt like.”

During these years, Frank continued to earn a living by photographing artists and writers for magazine print commissions, while also embracing the creative challenges of filmmaking alongside photography. His proximity to a diverse group of painters, sculptors, writers, and poets in the late 1950s would lead to boundary-pushing explorations like his first finished film, Pull My Daisy (1959), co-directed with artist Alfred Leslie, and filmed in Leslie’s own loft.

The Truth is Somewhere Between the Documentary and the Fictional

In 1968 Frank premiered his first feature-length film, Me and My Brother, at the Venice Film Festival. Built as a film within a film, the story prompts questions about participation in traditional society and culture, and about what experiences of life are understood as valid. “The truth is somewhere between the documentary and the fictional, and that is what I try to show,” Frank explained. “What is real one moment has become imaginary the next.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, as Frank turned his camera toward friends and neighbours, he also captured events of the time – manifested in political protests, music, poetry, and other aspects of social change and counterculture. During this period, Frank contributed cinematography to films directed by others and also spearheaded his own projects, which featured both recognisable figures and everyday folks on the street. In Me and My Brother, one character advises another: “Don’t make a movie about making a movie. MAKE IT. … Wouldn’t it be fantastic if you didn’t even have to have a piece of celluloid between you and what you saw?”

The Lines of My Hand

Frank’s photobook The Lines of My Hand offers a retrospective view of his career up until the date of its publication, in 1972. Pairing text and image, the book begins with early photographs made in Switzerland in the 1940s and ends with montages of film strips from Frank’s films of the 1950s and ’60s. Its title, perhaps a rumination on one’s past and one’s fate, is drawn from a sign pictured in a 1949 photograph of a Paris fortuneteller’s booth, on view here. This section of the exhibition also brings together a selection of older photographs that appear in the first Lustrum edition of the book.

The Lines of My Hand demonstrates Frank’s particular interest in the visual effects and meaning produced from combinations of images, either within a single photograph or formed by printing multiple negatives together to create a dense montage. In later editions, in keeping with his practice of revisiting and rearranging his images, Frank made changes to the photographs and graphic design and updated the book with his most recent works, using photocopies and notebooks to sequence the book’s new iterations.

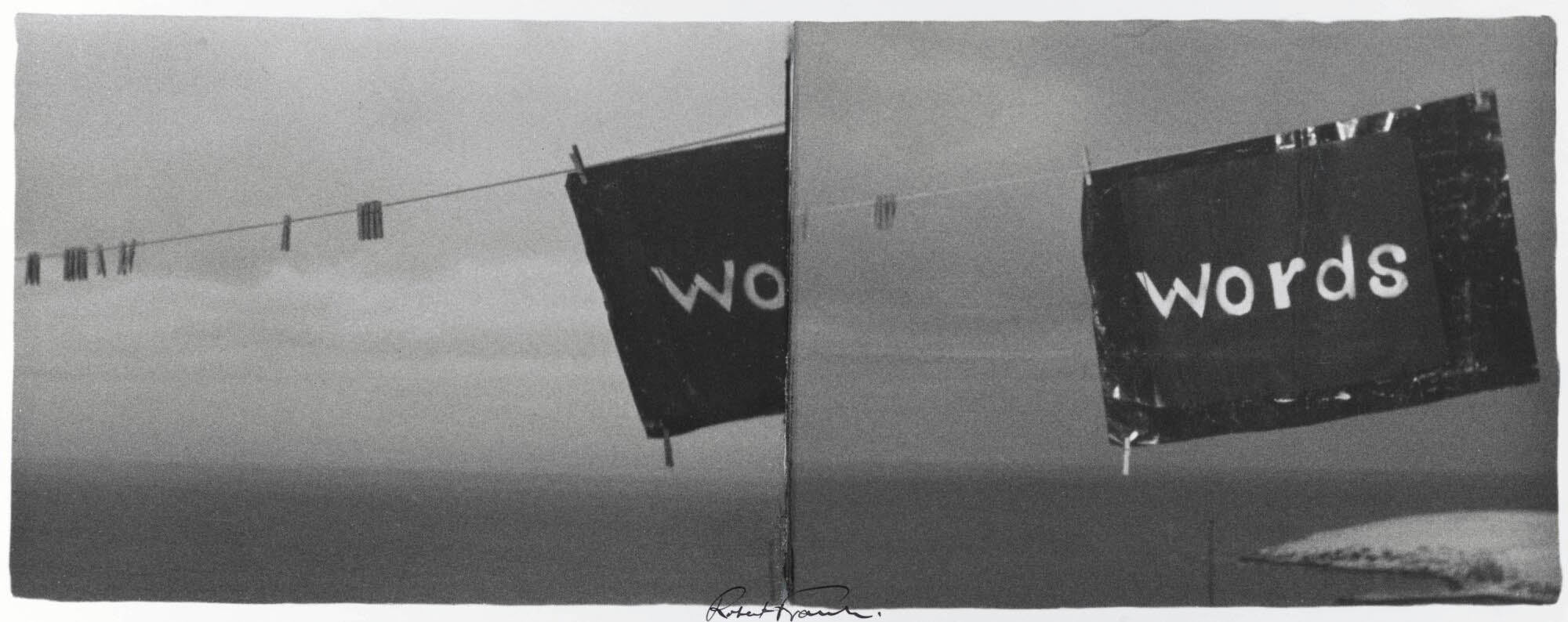

In Front of Me I Have the Sea

In 1970 Frank and Leaf relocated from New York City to the rural town of Mabou on Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada. The photographer Walker Evans, Frank’s friend and mentor, came to visit them soon after at their old fisherman’s cabin overlooking the sea. Evans’s photographs capture the house’s hulking wood stove and the clothesline strung outside it, elements of the couple’s daily routine that also became material for artistic work. Living there, they “learned a completely different rhythm of life.”

In Mabou, Frank’s work shifted its focus, becoming a means of processing his feelings, including profound grief. His change of environment, he acknowledged, had been significant: “All of a sudden you are in the company of something very powerful. … [But] what I wanted to photograph was not really what was in front of my eyes but what was inside.” For Frank, the sea was a dynamic ground against which to measure his life. He reflected, “I have a lot in back of me and that’s a tremendous pull, of what has happened in my life, backward. And in front of me I have the sea.”

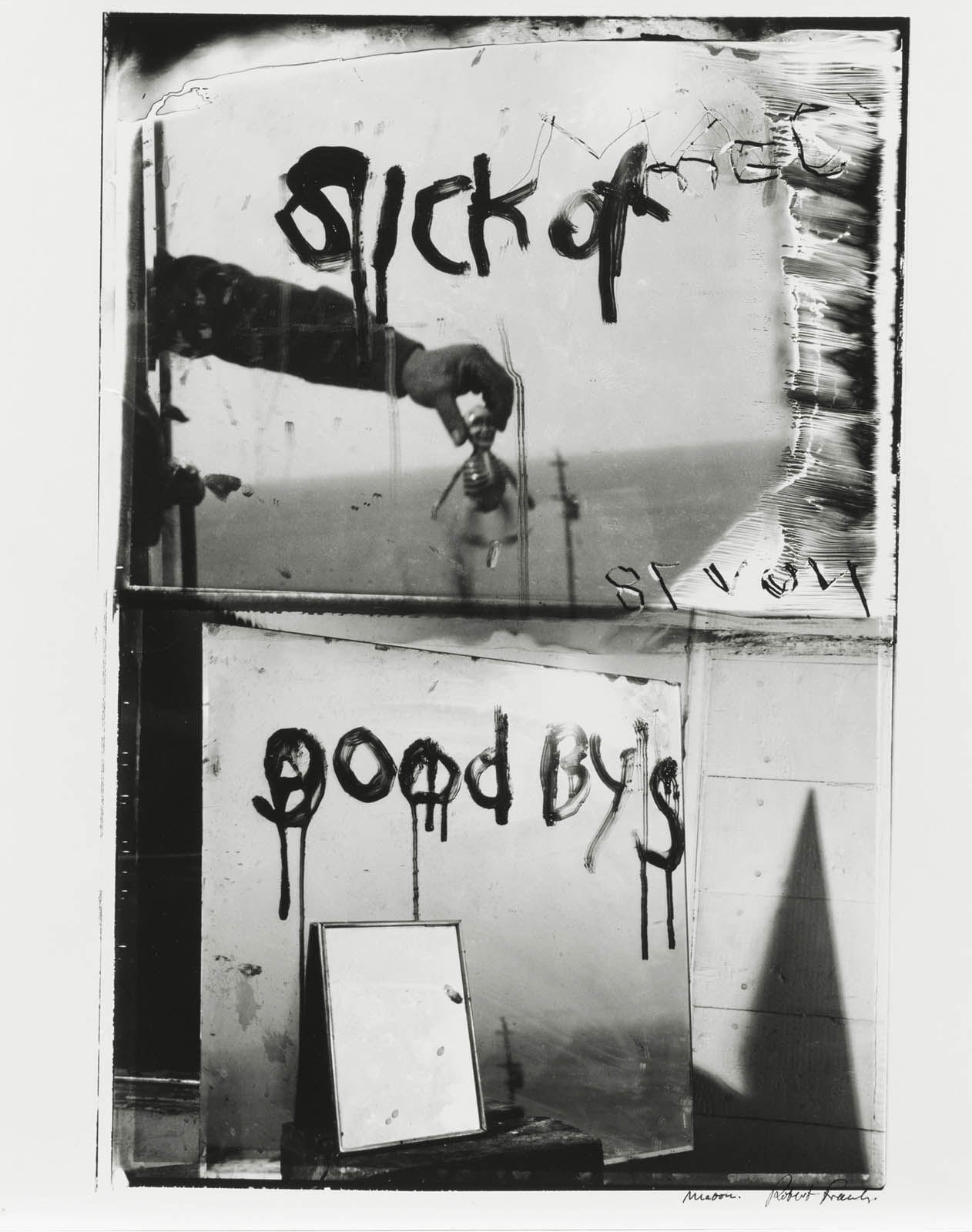

There Are Ways of Strengthening the Feeling

In the 1970s, Frank began regularly incorporating an instant print process, commonly known by the brand name Polaroid, into his work. He valued the immediacy of Polaroids, which enabled him to create an image instantly but then consider a work’s full composition over time. “I am no longer the solitary observer turning away after the click of the shutter,” Frank declared. “Instead I’m trying to recapture what I saw, what I heard and what I feel. What I know!”

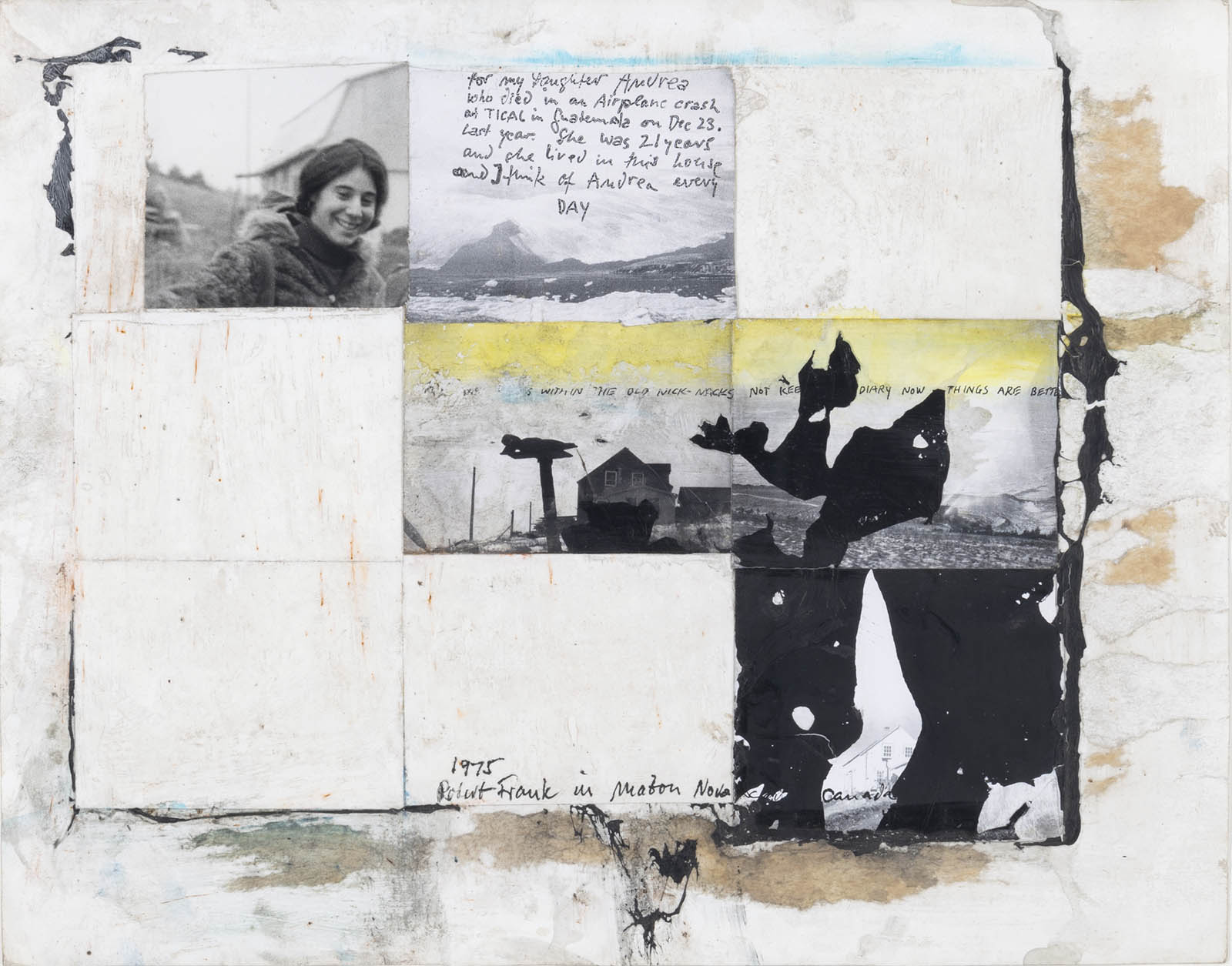

Throughout the rest of his career, Frank experimented with images by scratching words directly into the negatives and collaborating with printers to enlarge them into bigger prints and combinations. This process became especially significant for him after the sudden death of his daughter, Andrea, late in 1974. Frank began constructing monuments out of wood and materials around him in the landscape, which then figured into photographic memorials. “The Polaroid negative allows me to add that on it if it isn’t in the picture – I can put a word in it, I can combine two pictures – there are ways of strengthening the feeling I have,” Frank described.

The Video Camera Is Like A Pencil

In the early 1980s, Frank started using a Sony Portapak, a portable video camera that allowed him to instantly play back recordings. He could then erase, edit, and add new content on the tape. On video, Frank brought together fragments that at first seem unrelated, but through the choices he made while assembling them, offer a window into his personal preoccupations. Video, he noted, is “like a pencil. You can say things that you could never say with film.”

Home Improvements (1985), Frank’s first work in video, was made between New York City and Mabou. From it, the artist made a new work in which he captured still images of the footage using a large-format Polaroid camera. The resulting photographs feature snippets of found text; portraits of family members; and – in the last image – Frank himself, captured in a reflection behind his camera. “I’m always looking outside, trying to look inside,” Frank narrates in the video. “Trying to say something that’s true. But maybe nothing is really true. Except what’s out there. And what’s out there is always different.”

Memory Helps You – Like Stones In A River Help You To Reach The Shore

In his last decades, Frank’s work centered ever more upon his own life. Instead of travelling and looking outward, he found stories and compositions by panning his camera around his homes. His camera lingered on collected objects: figurines on the windowsill, postcards pinned to the wall, the typewriter on the table, and – always – photographs from years earlier. “I want to use these souvenirs of the past as strange objects from another age,” he once wrote. “They are partly hidden and curiously resonant, bringing information, messages which may or may not be welcome, may or may not be real.”

Frank also collected memories in his “visual diaries,” small, softcover books in which he, with his assistant, the photographer A-chan, arranged new and old pictures in sequences with personal resonance. Toward the end of his life, these photobooks became his main artistic output. Looking back at the souvenirs of his life – the settings in which it had taken place and the people who populated it – was incredibly generative: “Memory helps you,” he mused. “Like stones in a river help you to reach the shore.”

Text from MoMA

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Cocksucker Blues

1972

Gelatin silver print

19 7/8 × 15 7/8 inches (50.5 × 40.3cm)

The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Untitled (from Cocksucker Blues)

1972

Gelatin silver print

8 × 9 15/16 inches (20.3 × 25.2cm)

The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Pablo’s Bottle at Bleecker Street, New York City

1973

Gelatin silver print

19 13/16 × 15 7/8 inches (50.3 × 40.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Promised gift of Michael Jesselson

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Bonjour – Maestro, Mabou

1974

Robert Frank/The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation, via The Museum of Modern Art, NY

Frank hung an earlier landscape collage from a clothesline in a see-through frame, with the same landscape visible behind it.

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Andrea

1975

Five gelatin silver prints and ink on paper

10 15/16 × 13 7/8 inches (27.8 × 35.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, NY

Gift of the June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation in honor of Clément Chéroux and Lucy Gallun

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

After the death of Andrea Frank, his young daughter, in a plane crash, Frank memorialised her in a collage that he embellished with paint and a heartfelt, handwritten message.

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Mabou

1977

Gelatin silver print

7 5/16 × 19 5/16 inches (18.5 × 49cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of Robert and Gayle Greenhill

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Mabou Winter Footage

1977

Gelatin silver print

23 11/16 × 14 3/4″ (60.1 × 37.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Sick of Goodby’s

1978

Gelatin silver print

21 15/16 × 12 11/16 inches (55.8 × 32.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Purchase

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Fire Below – to the East America, Mabou

1979

19 3/16 × 22 13/16 inches (48.8 × 57.9cm)

Gelatin silver print enlarged from six Polaroid negatives with paint and ink

Gift of the artist, by exchange

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Look Out for Hope, Mabou – New York City

1979

Gelatin silver print

23 3/4 × 19 7/8 inches (60.3 × 50.5cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Promised gift of Michael Jesselson

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Los Angeles – February 4th – I Wake Up – Turn On TV

1979

Robert Frank/The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation, via The Museum of Modern Art, NY

In words and pictures he expressed a forlorn mood in a hotel room.

Robert Frank never recovered from the success of “The Americans.” On its publication in the United States in 1959, the book was initially excoriated as un-American, particularly in the photography magazines, for its sour, disillusioned take on life in this country. The rich looked bored, the poor desperate, the city fathers fatuous, and the flags threadbare or soiled. What’s more, specialists in photography faulted his technique for muddiness, grain and blur.

But in a slow burn, Frank’s willful violation of the conventional rules of photography was understood to serve the purpose of personal expression, and his dissection of national alienation and social divides was deemed prophetic. The smoke blew away, and “The Americans” stood clearly as a towering monument, one of the most important and influential books in the history of photography.

Frank hated that. In the early ’60s, he renounced still photography in favor of filmmaking. When he went back in the ’70s to making photographs – “in the time left over between films or film projects,” as he put it – he eschewed the street photography that had established his reputation. Instead, he mostly made studio or landscape pictures, which he liked to splice together into montages or embellish with scratched and stenciled words.

It’s this late work – if such a rubric can be applied to the six decades of movie, video and photo production that preceded his death at 94 in 2019 – that is the focus of “Life Dances On: Robert Frank in Dialogue,” opening Sunday at the Museum of Modern Art. Curated by Lucy Gallun, the exhibition marks the centenary of Frank’s birth and is his first solo show at MoMA. Although there are some omissions (his return to documentary photography in Beirut in 1991, for example), it presents as eloquent a case as can be made for this later art, often left in the shade by what came before.

Frank felt trapped by the expectations and pigeonholing that the lionization of “The Americans” induced, and he recoiled in horror at the prospect of repeating himself. Beyond that, he gave various explanations over the years for why he abandoned the 35 mm camera that he brandished like a sorcerer’s wand. He explained that he had lost faith in the capacity of a single photograph to convey the truth. And his search had turned inward. “The truth is the way to reveal something about your life, your thoughts, where you stand,” he said. He believed film was a better way to do that.

Film (joined by video in the ’80s) allowed Frank to record his feelings directly. In addition to clips from his movies and videos, the museum is showing “Robert Frank’s Scrapbook Footage,” an assemblage of previously unseen diaristic moving images, stitched together by Frank’s longtime editor, Laura Israel, and art director Alex Bingham – most ambitiously, in a five-screen installation that jumps between shots taken in the house in Mabou, Nova Scotia, and the apartment on Bleecker Street in the East Village in New York that Frank shared with his wife, artist June Leaf, as well as visits he made to his parents in Switzerland (where he was born) and to Russia. Topping it off, MoMA, which received Frank’s entire film and video archive as a gift from the artist, will present a complete motion-picture retrospective, from Nov. 20 to Dec. 11.

The aim is to reposition Frank’s reputation by showcasing the art that occupied most of his life. The trouble is: His genius as a photographer did not carry over to filmmaking. That was evident from the outset. His first completed movie, “Pull My Daisy,” a collaboration with artist Alfred Leslie, incorporated improvisation by the actors within the framework of a rehearsed script. With a voice-over by Jack Kerouac and appearances by Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Gregory Corso and Larry Rivers, the film resonates as a historical document of the Beat movement. As a movie, though, its madcap bohemianism is a clunky, leaden bore. First screened publicly in 1959 on a double bill with John Cassavetes’ similarly improvised “Shadows,” it wilts, woefully dated, when viewed today alongside that other milestone of independent American cinema.

Arthur Lubow. “‘The Americans’ Made the Photographer Robert Frank a Star. What Came Next?” on The New York Times website Sept. 12, 2024 [Online] Cited 15/12/2024

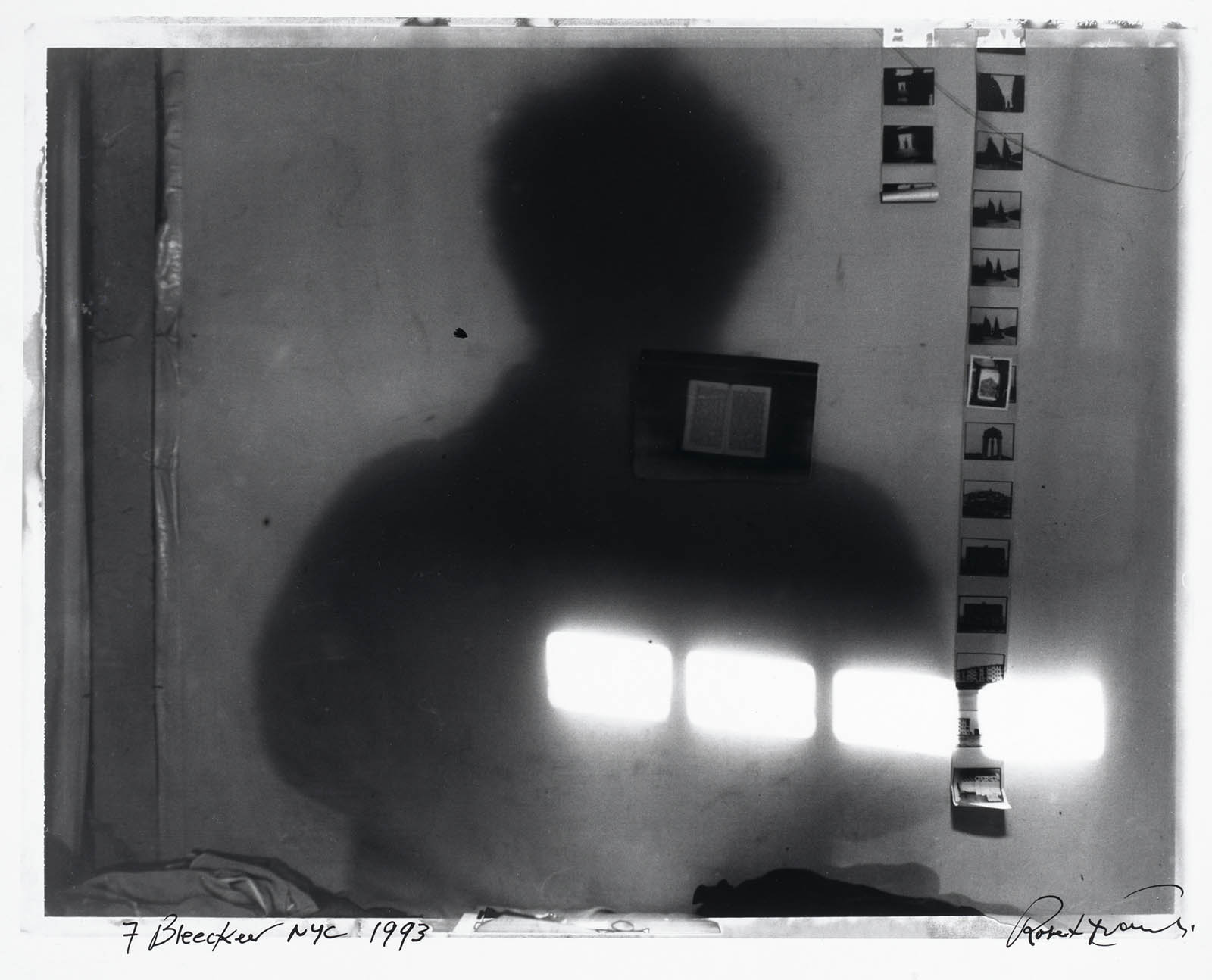

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

New York City, 7 Bleecker Street

September 1993

Gelatin silver print

15 15/16 × 19 13/16 inches (40.5 × 50.3cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Promised gift of Michael Jesselson

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

A self-portrait of the artist, in September 1993. Frank caught himself studying a strip of filmed images.

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

The Suffering, the Silence of Pablo

1995

Robert Frank/June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation, via Museum of Modern Art, NY

After the suicide of his son, Pablo Frank, the photographer composed this testament to his young, painful life.

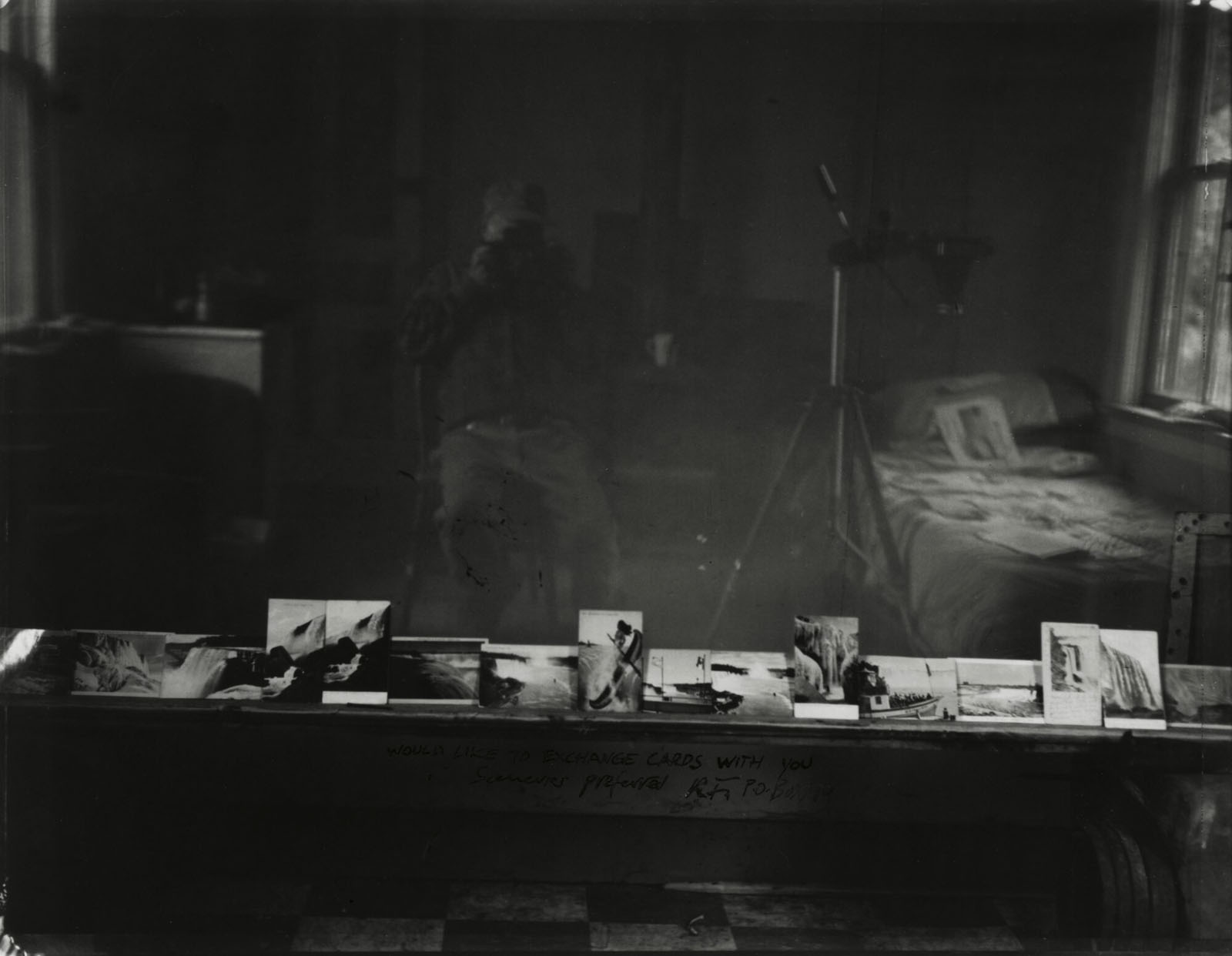

Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019)

Would Like to Exchange Cards with You, Souvenirs Preferred

2002

Gelatin silver print

10 13/16 × 13 7/8 inches (27.4 × 35.2cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of the artist

© 2024 The June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street

New York, NY 10019

Phone: (212) 708-9400

Opening hours:

10.30am – 5.30pm

Open seven days a week

![Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019) 'Untitled [The Lines of the Hand]' Paris, 1949-1951 Robert Frank (Swiss-American, 1924-2019) 'Untitled [The Lines of the Hand]' Paris, 1949-1951](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/frank-untitled-the-lines-of-the-hand.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.