Exhibition dates: 6th October, 2015 – 21st February, 2016

Curator: Amanda Maddox, assistant curator, Department of Photographs, the J. Paul Getty Museum.

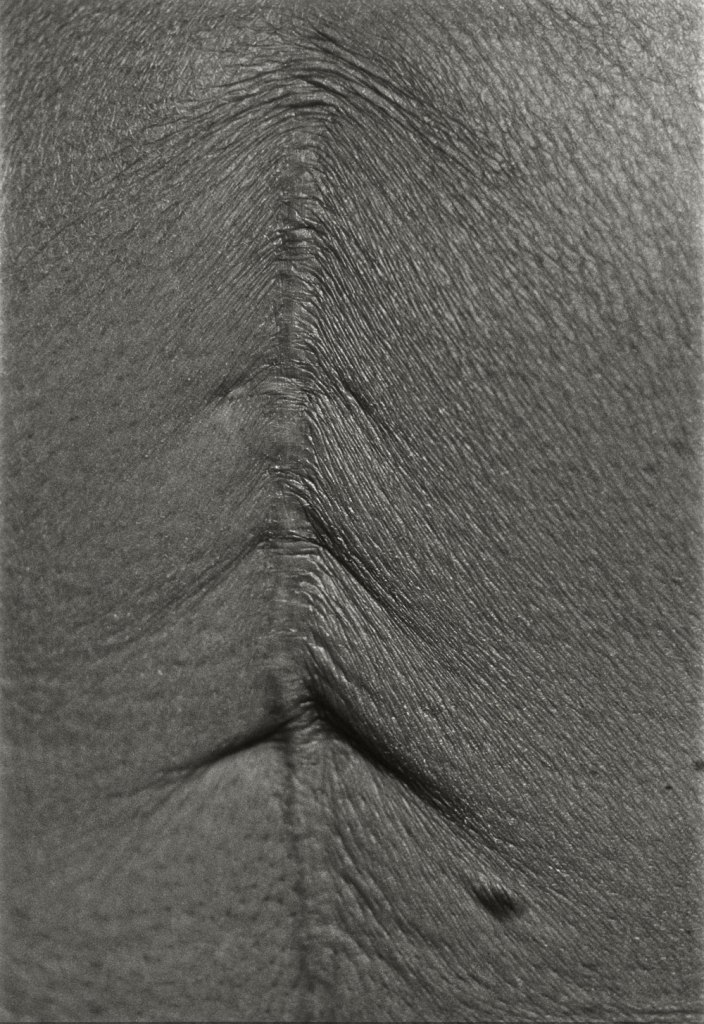

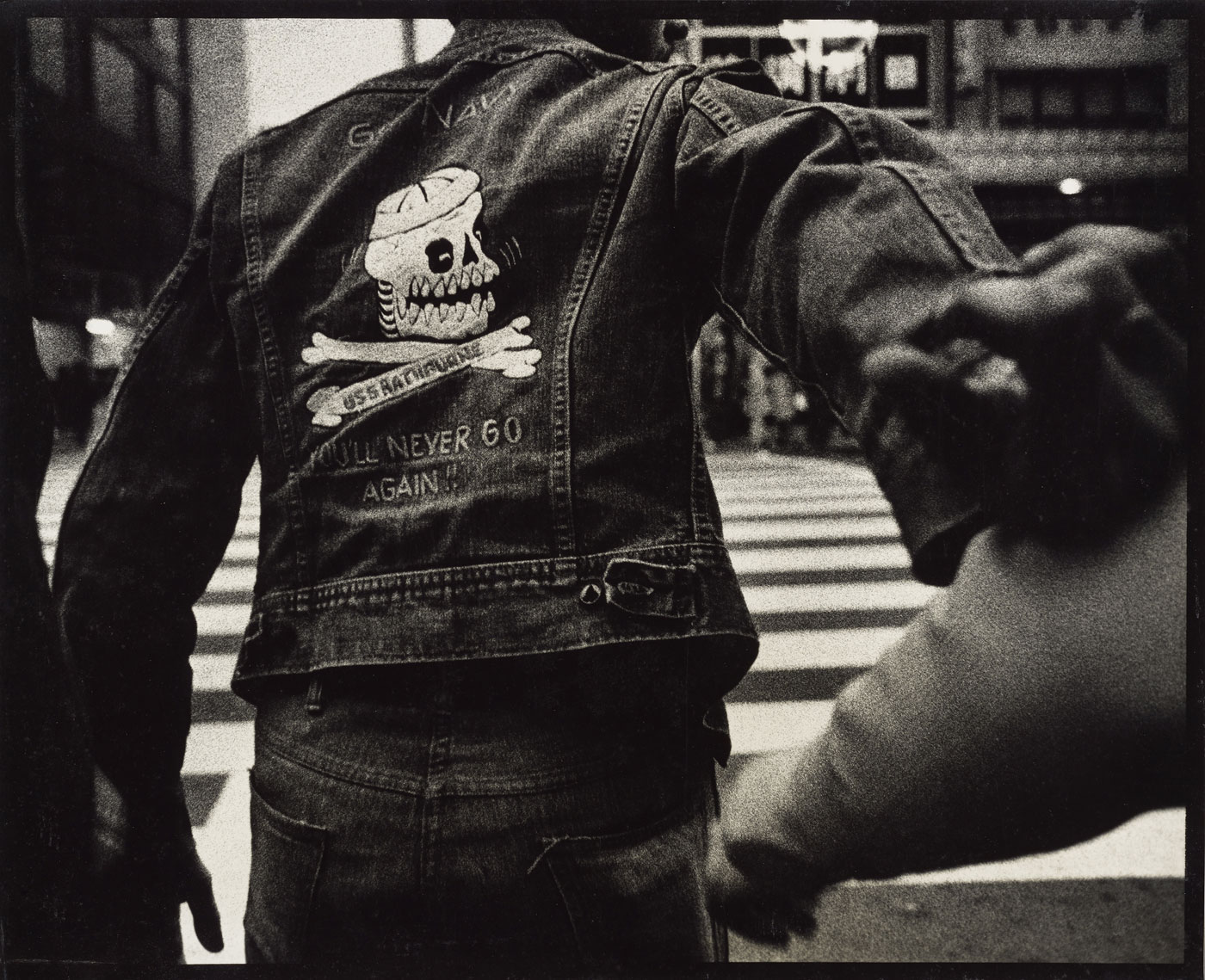

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokosuka Story #98

1976-1977

Gelatin silver print

45.5 x 55.9cm (17 15/16 x 22 in.)

Collection of Yokohama Museum of Art

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Digital file © Yokohama Museum of Art

This is a compelling body of work from Japanese artist Ishiuchi Miyako. I especially like the work from the 1970s period which is, I feel, stronger than the later work from the 1990s onwards. The 1970s work has a biting quality of observation and pathos that the later work somehow lacks. And, more generally, I have always loved Japanese photography from the 1950-70s for these very qualities.

You have to ask, why you would want to print an intimate object like your mother’s lipstick over a metre tall… other than to buy into the current fashion in contemporary photographic art, which is to print big. The same goes for some of the photographs of clothing in Miyako’s latest series ひろしま/ hiroshima (2007, below).

From a distance they may look fine, but when you get up close the image would just fall apart. No sense of the intimacy and privacy of the object here … except for the small prints, such as ひろしま/ hiroshima #41 (Kawamuki Eiko) (2007, below) which evidence the delicacy of the object as part of life, history and memory.

For me it is the essential quality of the earlier work – the large grain, the desperate looking individuals, the unnoticed corners of existence imagined in contrasty, handmade analogue prints – which really strikes at the emotions. The personal interweaved with the political. The brightness of hope mixed with a heavy dash of desolation.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the J. Paul Getty Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. All text from the J. Paul Getty Museum press release.

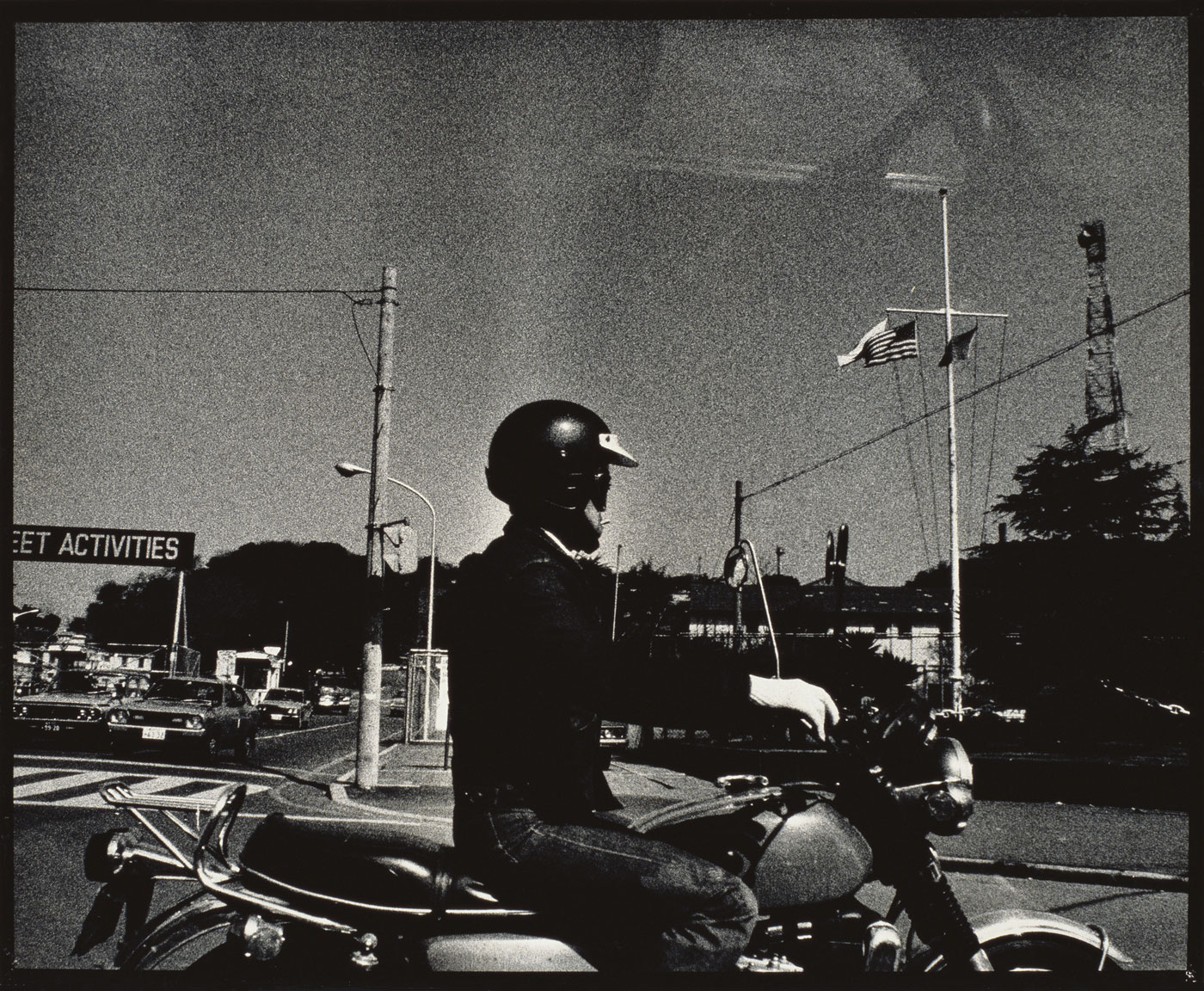

“In the 1970s Ishiuchi Miyako shocked Japan’s male-dominated photography establishment with Yokosuka Story, a gritty, deeply personal project about the city where she spent her childhood and where the United States established a naval base in 1945. Working prodigiously ever since, Ishiuchi has consistently fused the personal and political in her photographs, interweaving her own identity with the complex history of postwar Japan that emerged from the shadows cast by American occupation.

This exhibition is the first in the United States to survey Ishiuchi’s prolific career and will include photographs, books, and objects from her personal archive. Beginning with Yokosuka Story (1977-78), the show traces her extended investigation of life in postwar Japan and culminates with her current series ひろしま/ hiroshima, on view seventy years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.”

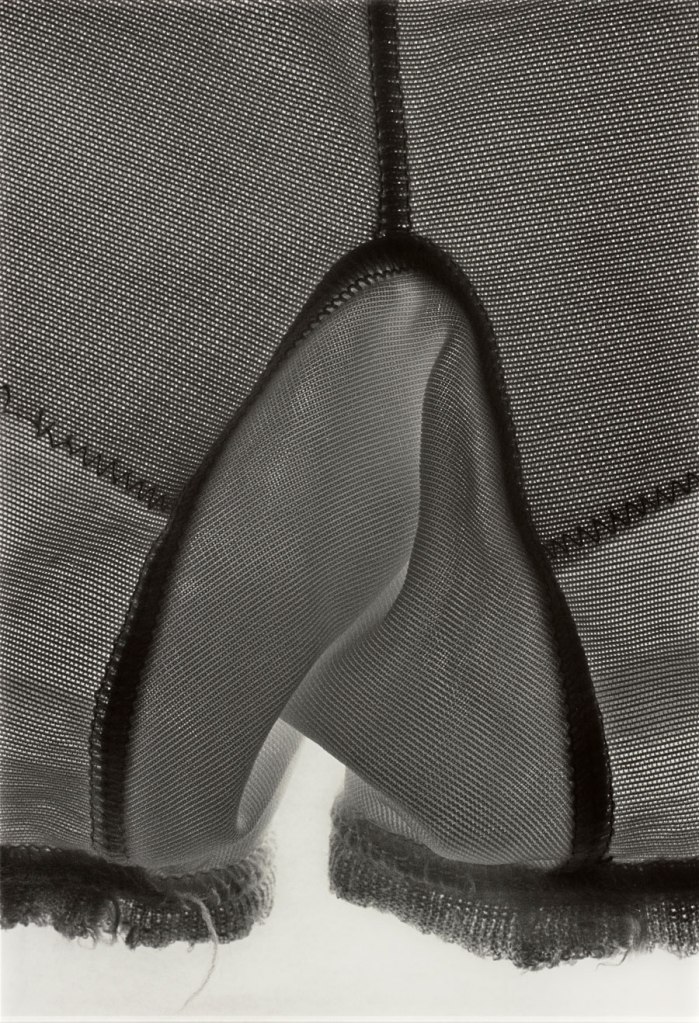

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokosuka Story #58

1976-1977

Gelatin silver print

45.5 x 55.9cm (17 15/16 x 22 in.)

Collection of Yokohama Museum of Art

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Digital file © Yokohama Museum of Art

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokosuka Story #62

1976-1977

Gelatin silver print

45.5 x 55.8cm (17 15/16 x 22 in.)

Collection of Yokohama Museum of Art

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Digital file © Yokohama Museum of Art

Survey exhibition includes Ishiuchi’s series ひろしま/ hiroshima, presented during the 70th anniversary year of the bombing of Hiroshima

The first major exhibition in the United States and the first comprehensive English-language catalogue on celebrated Japanese photographer Ishiuchi Miyako (born Fujikura Yōko in 1947) will showcase the artist’s prolific, groundbreaking career and offer new scholarship on her personal background, her process, and her place in the history of Japanese photography.

On view at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center from October 6, 2015 – February 21, 2016, Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows will feature more than 120 photographs that represent the evolution of the artist’s career, from her landmark series Yokosuka Story (1976-77) that established her as a photographer to her current project ひろしま/ hiroshima (2007-present) in which she presents images of garments and objects that survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

“About eight years ago, the Getty Museum began a concerted effort to expand our East Asian photography holdings and since that time work by Japanese photographers has become an important part of the collection,” explains Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “As part of this effort, the Museum acquired 37 photographs by Ishiuchi, some of them gifts of the artist, which constitute the largest holdings of her work outside Japan.” Potts adds, “Particularly poignant during this 70th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, and shown for the first time in an American institution, is Ishiuchi’s ひろしま/ hiroshima, a delicate and profound series of images depicting objects affected by the atomic blast.”

Born in Kiryū in the aftermath of World War II, Ishiuchi Miyako spent her formative years in Yokosuka, a Japanese city where the United States established an important naval base in 1945. She studied textile design at Tama Art University in Tokyo in the late 1960s before quitting school prior to graduation and ultimately pursuing photography. In 1975 she exhibited her first photographs under her mother’s maiden name, Ishiuchi Miyako, which she adopted as her own.

For the past forty years Ishiuchi has consistently interwoven the personal with the political in her work. Her longstanding engagement with the subject of postwar Japan, specifically the shadows that American occupation and Americanisation cast over her native country following World War II, serves as the organising principle of the exhibition. Across three interconnected yet distinct phases of her career, Ishiuchi explores the depths of her postwar experience.

Early Career: From Yokosuka Story to Yokosuka Again

Shortly after adopting photography as her means of personal expression, Ishiuchi began to take pictures of Yokosuka, where she and her family lived between 1953 and 1966. The prevalence of American culture there had shocked Ishiuchi as a child. Though it informed her love of pop music and denim jeans, it also caused her to harbour fears of the U.S. naval base and develop a hatred of the city. Armed with a camera and fuelled by painful memories, Ishiuchi returned to Yokosuka in the 1970s to address her fears. The act of photographing old haunts, as well as unfamiliar places, proved to be a catharsis. Using money her father had saved for her wedding, Ishiuchi financed the production of prints, as well as the related publication, Yokosuka Story, which she named after the title of a Japanese pop song.

In 1953 Ishiuchi and her family left their home in Kiryū for Yokosuka, a port city with a large U.S. naval base. Shocked by the prevalence of American culture there, she quickly developed fears of the base, its soldiers, and specific neighbourhoods. Harbouring these anxieties for years, Ishiuchi viewed Yokosuka as “a place that I thought I’d never go back to, a city I wouldn’t want to walk in twice” after leaving in 1966.

But Ishiuchi eventually returned on weekends between October 1976 and March 1977 to photograph the city for her first major project. Filled with emotion and fuelled by hatred and dark memories, Ishiuchi traversed the city on foot and by car, chauffeured by her mother who worked as a driver for the U.S. military. Questioned by police multiple times while making this work, Ishiuchi experienced the danger she sensed during childhood.

Using a darkroom she set up in her parents’ home, Ishiuchi printed the photographs on view here for an exhibition at Nikon Salon in Tokyo in 1977. The work features black borders and heavy grain, which represent memories Ishiuchi “coughed up like black phlegm onto hundreds of stark white developing papers.” With money her father reserved for her wedding, Ishiuchi financed the production of prints, as well as the related publication, Yokosuka Story, named after the title of a Japanese pop song.

“With Yokosuka Story, and ultimately the other series she produced at the beginning of her career, Ishiuchi attempted to transfer her emotions and dark memories into the prints through physical means,” says Amanda Maddox, assistant curator of photographs at the Getty Museum and curator of the exhibition. “By carefully controlling how she processed film, and by intentionally printing the photographs with heavy grain and deep black tones, she injected her feelings into the work. She loved working in the darkroom, in part because the tactile nature of processing film and printing photographs related to her training in textile production.”

Interested in blurring the boundary between documentation and fiction, Ishiuchi tested the limits of this approach in her second major series Apartment. Isolating derelict, cheaply constructed apartments that resembled the cramped one-room apartment that her family occupied in Yokosuka, Ishiuchi photographed ramshackle facades, rooms, and interiors of buildings in Tokyo and Yokohama. Despite criticism of the series from other photographers, Ishiuchi ultimately earned the prestigious Ihei Kimura Memorial Photography Award for her book Apartment.

When Ishiuchi exhibited Yokosuka Story at Nikon Salon in 1977, the chairman of the Salon’s steering committee asked about her next project. Without hesitation, she responded “apartments.” Although she had only photographed a few apartment buildings in Yokosuka, Ishiuchi recognised the potential of this subject. For thirteen years she and her family lived in a cheaply constructed postwar building in Yokosuka, inhabiting a tiny apartment with an earthen floor and communal bathroom.

In 1977 Ishiuchi began to seek out similarly derelict apartments in Tokyo and other cities. With the permission of residents, Ishiuchi photographed rooms and interiors in the buildings, occasionally portraying the occupants. Her images inside these cramped quarters reveal the grim condition of each building – peeling paint, dimly lit hallways, and stained walls “steeped in the odour of people who move about” – and suggest many stories housed within these living spaces.

Ishiuchi wanted the disparate interiors featured in Apartment to feel as though one building contained them. Her desire to create a fictitious place – with different apartments from various locations presented together as one residential complex – met with criticism from traditional documentary photographers, but Ishiuchi ultimately earned the prestigious 4th Kimura Ihei Memorial Photography Award for her book Apartment.

Endless Night, a series that developed as a result of her work on Apartment, features buildings across Japan that formerly functioned as brothels. In 1958 the Japanese government began to enforce an anti-prostitution law, causing many red-light districts to close. Brothels were either abandoned or transformed into inns, hotels, or private accommodations. With memories of walking past a red-light district in Yokosuka on her way to school, Ishiuchi felt a connection to this subject matter and to the women who once inhabited these places, their traces still palpable.

While photographing for Apartment, Ishiuchi sensed something “eerie” inside several buildings. She later discovered that those particular locations had formerly functioned as brothels. In 1958 the Japanese government began to enforce an anti-prostitution law, and as a result many red-light districts closed and some brothels became private accommodations or inns. Growing up in Yokosuka, where she passed through a red-light district on her way to school and where her identity as a woman was shaped by the masculine energy that emanated from the U.S. naval base, Ishiuchi felt particularly drawn to this subject.

Intent on photographing red-light neighbourhoods across Japan, Ishiuchi started in Tokyo and eventually traveled to Sendai and Ishinomaki in northern Japan, as well as to Osaka, Kyoto, and Nara in the Kansai region. Entering these buildings proved an emotional experience for Ishiuchi, which she described as follows: “The space of the entryway froze me, the intruder, in my tracks. Inhaling it, I felt ill, as if I might vomit… Though I had only come to take photographs, all of the women who had once inhabited this room came wafting out from the stains on the walls, the shade under the trees, the shine on the well-tread stairs.”

In 1980 Ishiuchi returned to depict places not represented in Yokosuka Story, targeting locations that terrified her. For this new project she focused on Honchō – the central neighbourhood where the presence of America felt especially concentrated, with the U.S. naval base and EM (Enlisted Men’s) Club located there. For six months Ishiuchi rented an abandoned cabaret on Dobuita Dōri (Gutter Alley). With the help of friends she converted the cabaret into an exhibition space, where she displayed the new work alongside images from Yokosuka Story. She continued to photograph in Yokosuka intermittently until 1990, when the dilapidated EM Club was finally razed. Her final Yokosuka projects, Yokosuka Again, 1980-1990, represents a triumph over the conflicting emotions she possessed toward the city.

Midcareer: On the Body

Following her exhaustive investigation of Yokosuka, Ishiuchi contemplated quitting photography altogether. But as she celebrated her 40th birthday in 1987, she recognised that the traces of time and experience left on her body could inspire new work and spark another phase of her career. For 1·9·4·7, titled after her birth year, she approached friends also born that year and asked to photograph them – specifically their hands and feet. As news of the project spread, Ishiuchi expanded the series to include women she did not know. In intimate, close-up views, Ishiuchi draws attention to the calluses, hangnails, wrinkles, and other imperfections that develop on the skin during a lifetime of activity.

Ultimately Ishiuchi chose to eliminate the facial portraits from the series, enhancing the anonymity of the project, to focus on extremities that are exposed to the world but often overlooked. In intimate, close-up views, she draws attention to the calluses, hangnails, wrinkles, and other imperfections that develop on the body during a lifetime. Ishiuchi includes the occupation of each sitter in captions published in the book 1·9·4·7 but excludes that information in exhibitions. Though the women remain anonymous, their body parts, photographed with great sensitivity, appear very distinct.

Inspired by 1·9·4·7, Ishiuchi developed many projects that focused on the body as subject. Among the most powerful is Scars, a series she began in 1991 that remains a work in progress. As reminders of past trauma and pain, scars evoke memories that the skin retains on its surface. Ishiuchi regards these marks as battle wounds and symbols of victory. She also likens them to photographs, which serve simultaneously as visible markers of history and triggers of personal memory. For each large-scale print, Ishiuchi provides only the year that a wound was inflicted as well as its cause – such as accident, illness, attempted suicide, or war.

In her book Scars (Tokyo: Sokyū-sha, 2005), Ishiuchi explains her interest in this subject as follows: “Scars themselves carry a story. Stories of how each person was very sad, or very hurt, and it is because the memory remained in the form of the scar that the story can be narrated in words.” As reminders of past trauma and pain, scars are memories inscribed onto the body and retained into the present moment. Yet rather than view scars only as blemishes or manifestations of injury, Ishiuchi perceives them as battle wounds and symbols of victory over possible defeat. She likens them to photographs, which also serve simultaneously as visible markers of history and triggers of personal memory.

Scars developed as a sideline interest when Ishiuchi noticed old wounds on some of the men she photographed for a project called Chromosome XY. The stories associated with each scar are distilled in the titles, but Ishiuchi provides only the year that a wound was inflicted and its cause – such as accident, illness, suicide, and war. Photographing scars since 1991, Ishiuchi believes that some kind of wound – healed or open – exists on every body.

Fascinated by the idea that a Polaroid camera operates as a portable, self-contained darkroom, Ishiuchi often shared Polaroid portraits with sitters immediately after they were produced. Her series Body and Air features some of these Polaroids – fragments of the body – grouped together by sitter. One of the people included in Body and Air is Ishiuchi’s mother; though her mother was camera-shy, she found the playful, interactive nature of this particular project appealing. Her acquiescence to serve as a photographic subject ultimately laid the foundation for Ishiuchi’s next major series.

An essential aspect of Ishiuchi’s photographic process involves work that must occur in the darkroom: developing film and printing negatives. The tactile nature of the medium immediately appealed to her, in part because it related to her training in textile design but also because it offered room to express her emotions via the contrast, grain, and texture she controlled in the print. She has noted that “photographs are my creations. I create them, brooding in the darkroom, immersed in chemicals.”

Recent Projects: Life and Death

Shortly before her mother died in 2000, Ishiuchi began to photograph her skin and face. While select photographs from this period can be found in the series Scars and Body and Air, Ishiuchi eventually generated a project specifically about her mother. Spurred by her decision to photograph her mother’s personal effects rather than simply dispose of them, Ishiuchi created the series Mother’s, in which she includes images of old shoes, girdles, and used lipstick once owned by her mother as well as photographs of her mother’s body made in 2010, soon before her death.

Ishiuchi’s mother died in 2000, about one year after Ishiuchi began photographing her. Unsure if she should keep or dispose of her mother’s personal effects, Ishiuchi decided to photograph them. She taped worn chemises and girdles to the sliding glass door in her parents’ home, allowing the sun to backlight the undergarments when photographed. Old shoes, dentures, used lipstick cases, tattered gloves, and other accessories owned by her mother also feature as subjects. Combining these images with the pictures of her mother made before she died, Ishiuchi generated a somber, gentle portrait with the series Mother’s. When exhibiting this work at the Venice Biennale in 2005, Ishiuchi realised that sharing these intimate views of her mother’s life resonated with many visitors, thus transforming the work from a private expression of sorrow into a powerful, universal eulogy.

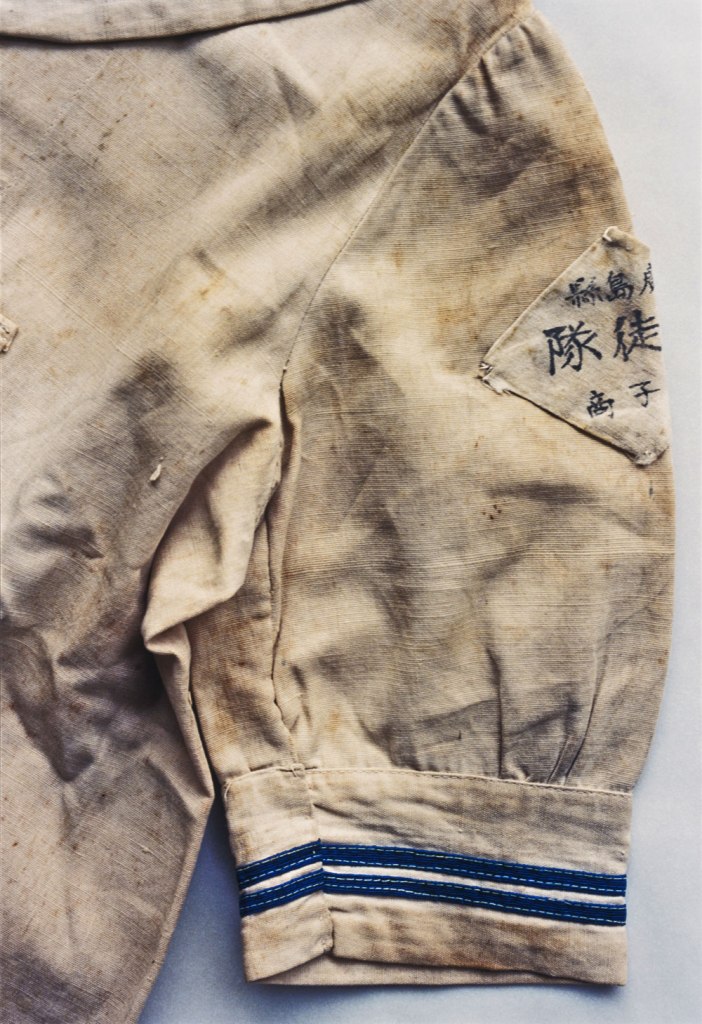

The shared experience of trauma as a photographic subject registers most poignantly in Ishiuchi’s current series ひろしま/ hiroshima. Ishiuchi first visited Hiroshima when commissioned to photograph there in 2007. She chose as her principal subjects the artefacts devastated by the U.S. atomic bombing of the city, now housed at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Aware that Tōmatsu Shōmei, Tsuchida Hiromi, and others had previously photographed some of the same objects, Ishiuchi nevertheless wanted to photograph this material in order to present it from a different, distinctly feminine perspective. (The title of the series ひろしま/ hiroshima intentionally includes the word Hiroshima in Hiragana, a Japanese writing system that women used extensively in previous eras).

The title of the project, ひろしま / hiroshima, includes the word Hiroshima written in Hiragana, a Japanese writing system that women used extensively in previous eras. Images in this series typically feature objects once owned by women, primarily garments that had been in direct contact with their bodies at the time of the bombing. Ishiuchi sometimes speaks to the objects while photographing them and initially used a light box to illuminate fabrics, conjuring the ghostlike auras of the victims – which the artist reinforces by “floating” the photographs on the walls – and alluding to the “artificial sun” of the bomb. But the effects of irradiation – visible in the holes, stains, and frayed edges – are offset by the fashionable textiles, vibrant colours, and intricate, hand-stitched details. Included in the titles are names of individuals who donated each article to the Peace Memorial Museum, further animating the stories these photographs tell.

Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows is curated by Amanda Maddox, assistant curator, Department of Photographs, the J. Paul Getty Museum. A fully illustrated scholarly catalogue, with essays by Maddox; Itō Hiromi, poet; and Miryam Sas, professor, University of California, Berkeley, accompanies the exhibition.

Text from the press release; text from “Ishiuchi Miyako: Postwar Shadows,” published online 2015, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Cited 03/02/2016.

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokosuka Story #61

1976-1977

Gelatin silver print

45 x 55.3cm (17 11/16 x 21 3/4 in.)

Collection of Yokohama Museum of Art

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Digital file © Yokohama Museum of Art

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokosuka Story #34

1976-1977

Gelatin silver print

45.2 x 55.7cm (17 13/16 x 21 15/16 in.)

Collection of Yokohama Museum of Art

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Digital file © Yokohama Museum of Art

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokosuka Story #64

1976-1977

Gelatin silver print

45.5 x 55.9cm (17 15/16 x 22 in.)

Collection of Yokohama Museum of Art

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Digital file © Yokohama Museum of Art

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokosuka Story #121

1976-1977

Gelatin silver print

43.7 x 54cm (17 3/16 x 21 1/4 in.)

Collection of Yokohama Museum of Art

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Digital file © Yokohama Museum of Art

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Yokosuka Story #73

1976-1977

Gelatin silver print

43.7 x 53.7cm (17 3/16 x 21 1/8 in.)

Collection of Yokohama Museum of Art

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Digital file © Yokohama Museum of Art

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Apartment #1

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

50.5 x 60.3 x 2.5cm (19 7/8 x 23 3/4 x 1 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Ishiuchi Miyako

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Apartment #55

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

50.5 x 62.8cm (19 7/8 x 24 3/4 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Ishiuchi Miyako

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Apartment #47

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

50 x 60 x 2.5cm (19 11/16 x 23 5/8 x 1 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Ishiuchi Miyako

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Apartment #19

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

50 x 60 x 2.5cm (19 11/16 x 23 5/8 x 1 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Ishiuchi Miyako

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Apartment #10

1977-1978

Gelatin silver print

50 x 60cm (19 11/16 x 23 5/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Ishiuchi Miyako

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Endless Night #2

1978-1980

Gelatin silver print

78.7 x 106.5cm (31 x 41 15/16 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Endless Night #71

1978-1980

Gelatin silver print

78.7 x 106.5cm (31 x 41 15/16 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Endless Night #98

1978-1980

Gelatin silver print

50 x 63cm (19 11/16 x 24 13/16 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

EM Club #28

1990

Gelatin silver print

77.2 x 104.8cm (30 3/8 x 41 1/4 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

1·9·4·7 #61

1994

Gelatin silver print

39.5 x 54.6cm (15 9/16 x 21 1/2 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

1·9·4·7 #15

1988-1989; print 1994

Gelatin silver print

39.4 x 54.5cm (15 1/2 x 21 7/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Gift of Ishiuchi Miyako

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

1·9·4·7 #11

1988-1989

Gelatin silver print

85.7 x 114.2cm (33 3/4 x 44 15/16 x in.)

Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

1·9·4·7 #11

1988-1989

Gelatin silver print

85.7 x 114.2cm (33 3/4 x 44 15/16 x in.)

Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

1·9·4·7 #49

1988-1989

Gelatin silver print

85.7 x 114.2cm (33 3/4 x 44 15/16 x in.)

Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Scars #45 (Illness 1955)

2000

Gelatin silver print

111 x 76.7cm (43 11/16 x 30 3/16 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Scars #27 (Illness 1977)

1999

Gelatin silver print

160 x 108cm (63 x 42 1/2 in.)

Collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Mother’s #57

2004

Chromogenic print

19.2 x 28.8cm (7 9/16 x 11 5/16 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Mother’s #35

2002

Chromogenic print

107.5 x 74cm (42 5/16 x 29 1/8 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Mother’s #49

2002

Gelatin silver print

107.5 x 74cm (42 5/16 x 29 1/8 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

Mother’s #16

2001

Gelatin silver print

Framed: 107.5 x 74cm (42 5/16 x 29 1/8 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

ひろしま/hiroshima #69 (Abe Hatsuko)

2007

Chromogenic print

108 x 74cm (42 1/2 x 29 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

© Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

ひろしま/hiroshima #9 (Ogawa Ritsu)

2007

Chromogenic print

187 x 120cm (73 5/8 x 47 1/4 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

ひろしま/hiroshima #33 (Nishimoto Oyuki)

2007

Chromogenic print

108 x 74cm (42 1/2 x 29 1/8 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

ひろしま/hiroshima #60 (Abe Hatsuko)

2007

Chromogenic print

33.5 x 23cm (13 3/16 x 9 1/16 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

ひろしま/hiroshima #97F (Wada Yasuko)

2010

Chromogenic print

108 x 74cm (42 1/2 x 29 1/8 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

ひろしま/hiroshima #82 (Uesugi Ayako)

2007

Chromogenic print

23 x 33.5cm (9 1/16 x 13 3/16 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

Ishiuchi Miyako (Japanese, b. 1947)

ひろしま/hiroshima #41 (Kawamuki Eiko)

2007

Chromogenic print

23 x 33.5cm (9 1/16 x 13 3/16 in.)

Courtesy of and © Ishiuchi Miyako

The J. Paul Getty Museum

1200 Getty Center Drive

Los Angeles, California 90049

Opening hours:

Daily 10am – 5pm

![Gotthard Schuh (Swiss, 1897-1969) 'Inseln der Götter' (Islands of the gods) [book cover] 1941 Gotthard Schuh (Swiss, 1897-1969) 'Inseln der Götter' (Islands of the gods) [book cover] 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/insel-de-gotter.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.