Exhibition dates: 11th April – 1st September 2024

This exhibition is a collaboration between Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum, Alexander Turnbull Library, and Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena

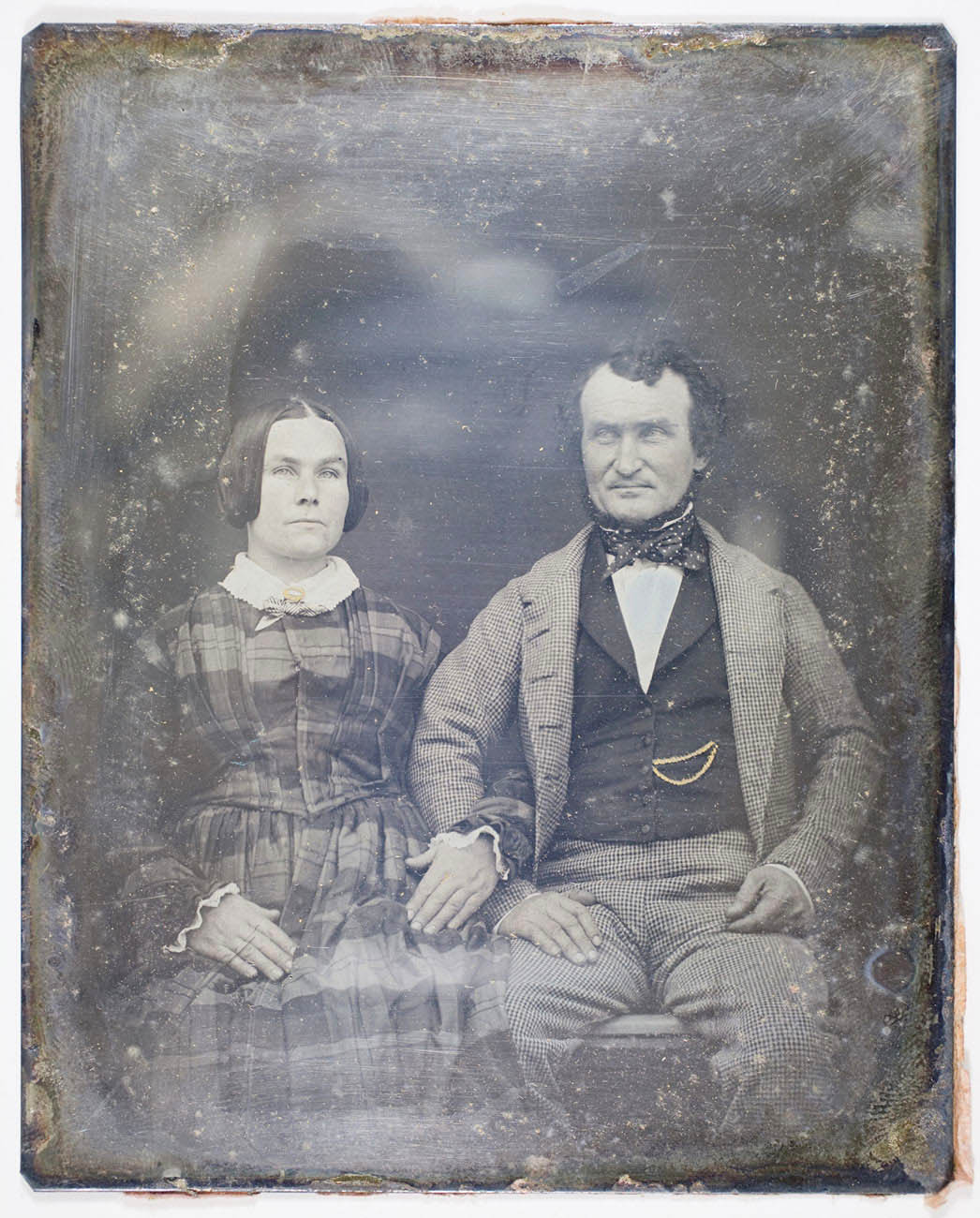

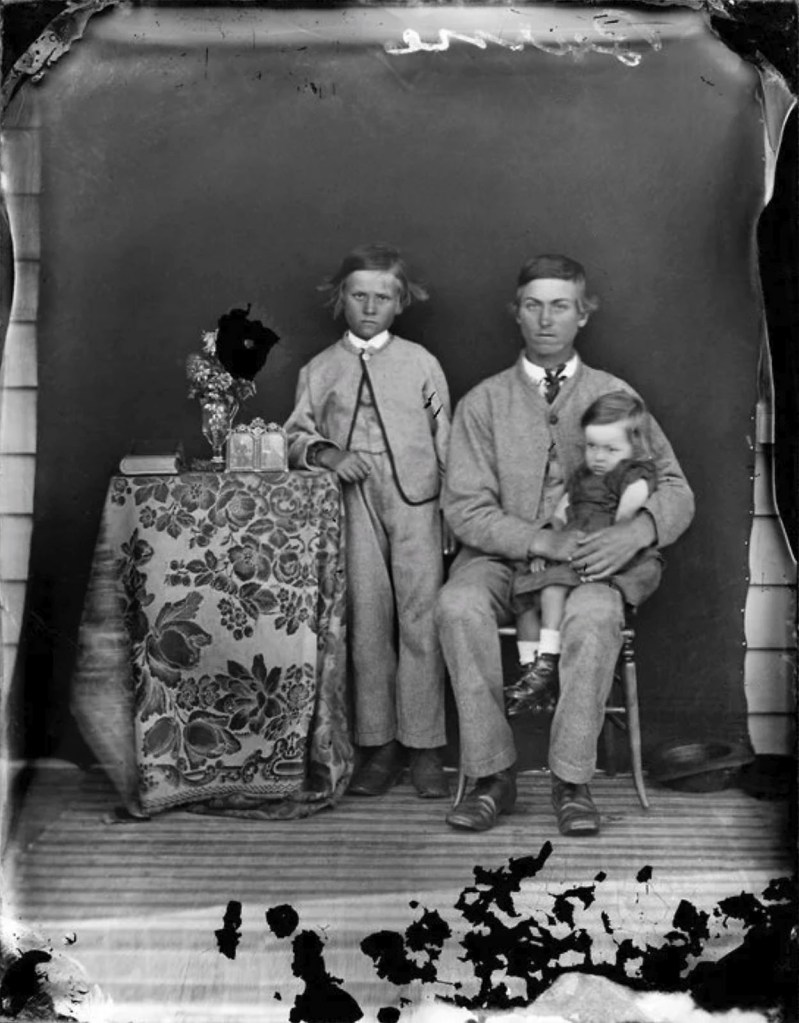

Hartley Webster (New Zealand, 1818-1906) (Attributed to)

Jane and Alexander Alison

30 June 1852

Half-plate daguerreotype, passe-partout mount

130 mm. x 100 mm. (plate)

Auckland Museum Collection

Hartley Webster was Auckland’s first resident professional photographer, but despite his longevity and his unique role in the growth of photography in 19th century New Zealand his death in 1906 passed without an obituary.

~ Keith Giles

Then and now

I went to the annual Melbourne Rare Book Fair at the University of Melbourne recently. There, albums of early photographs of Aotearoa were available to purchase for nearly AUD$7,000. These days, colonial photographs from both Australia and New Zealand are only for those that can afford them – to on sell, to secrete away in collections, to act as memento mori.

The colonial settler lens focused on landscape photography and portrait photographs of white settlers and Indigenous people, Māori “captured” by the camera. Professor Angela Wanhalla observes that, “Photographs are complicit in colonialism because they were used to document the impacts of migration, settlement and land transformation.”1

Through the use of material culture studies – an interdisciplinary field that examines the relationship between people and their things, the making, history, preservation, and interpretation of objects – we can study colonial photographs and the albums that hold them in order to understand how photographs are complicit in colonialism, and how colonial photographs can become a “rich sources for historians trying to uncover and understand late-nineteenth-century life.”2

Historian Jules Prown outlined material culture and a suggested approach. He wrote:

“Material culture as a study is based upon the obvious fact that the existence of a man-made object is concrete evidence of the presence of a human intelligence operating at a time of fabrication. The underlying premise is that objects made or modified by man reflect, consciously or unconsciously, directly or indirectly, the beliefs of individuals who made, commissioned, purchased, or used them, and by extension the beliefs of the larger society to which they belonged.”3

Colonial photographers and their photographs then, reflect the dominant hegemonic, patriarchal society to which they belong. According to Jarrod Hore they were engaged in “settler colonial work” because they “mobilised and visually reorganised local environments in the service of broader settler colonial imperatives.”4

Evidence of this reorganisation and the loss of individual and cultural identity can be found in the photographs Māori people. While the names of the Pākehā commercial photographic studios that took photographs of Māori might be known, the identity of the Māori subjects were often not recorded. Sapeer Mayron observes that, “Māori in particular were often photographed and their names and identities not preserved, called instead “Māori celebrities” and dressed with props in the artists’ studios” while in the same article Shaun Higgins, Auckland Museum pictures curator and curator of this exhibition observes, “When you’re documenting, you’re not this invisible entity that’s just documenting everything, you are making choices. You are, in effect, not documenting neutrally, but with your own agenda.”5 Again, photographers using material culture to record what was around them, reflecting, “consciously or unconsciously, directly or indirectly, the beliefs of individuals who made, commissioned, purchased, or used them, and by extension the beliefs of the larger society to which they belonged.”

But while Pākehā commercial photography captured Māori as ethnographic photographic subjects, conversely the Māori themselves were not always passive subjects in their own representation, posing for the camera as they wanted to be seen, or using the camera themselves to document family and culture. Indeed (and applicable to early New Zealand photographs as well as early Australian ones), academics such as the Australian Jane Lydon in her important books Eye Contact: Photographing Indigenous Australians (2005) and Photography, Humanitarianism, Empire (2016) note that these photographs were not solely a tool of colonial exploitation. Lydon articulates an understanding in Eye Contact that the residents of Coranderrk, an Aboriginal settlement near Healsville, Melbourne, “had a sophisticated understanding of how they were portrayed, and they became adept at manipulating their representations.”

Professor Angela Wanhalla also enunciates that the relationship between the camera and the Māori whānau (extended family group) is multilayered and complicated:

“At different times, and depending on the context, Māori embraced or rejected photography. Because of its colonial implications, Māori whānau and communities have a complicated relationship with the camera. But, as scholars Ngarino Ellis and Natalie Robertson argue, there is evidence it was regarded as friend as much as foe. …

Colonial photographs are culturally dynamic. Their integration into Māori life means they do not just depict relationships but are imbued with them. As such, photographs are taonga (treasures) and connect people across time and space.”6

Then and now, through the photographs ‘materiality’ and their role as sensory things that are held and used as well as viewed – the photographs imbued with the spirit of people long past – images of Indigenous ancestors taken by Māori and Pākehā act as talisman against the vicissitudes of colonial oppression.

They picture a land and culture which has irrevocably changed but the photographs can can still bring past stories into present life, which then regenerate the spirit of the ancestors into the presence of contemporary Māori families. With the recent acts of regression against the Māori people by the current New Zealand government, any object, any taonga (treasures) which connect people across time and space and make them stronger, is to be valued, especially if the photographs upend the tropes of colonial power and control.

As Joyce Campbell observes of these photographs, “The living connection to the sitter was the same as to a carved ancestor, or any other manifestation… It is easy to see that how they lived intersects with how we live now, and also to recognize the ways in which it does not. If these photographs are technically rough, or worn, we easily look past all that to engage with an image of another person or place. The images defy the notion that we need hyper-reality, immersion, massive scale, vivid colour or idealised beauty in order to achieve psychic proximity.”

In psychic proximity and unity, across time.

Strength people, strength. Hope, spirit, respect, strength.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Extract from Professor Angela Wanhalla. “The past in a different light: how Māori embraced – and rejected – the colonial camera lens,” on The Conversation website April 11, 2024 [Online] Cited 10/08/2024

2/ Jill Haley. “Otago’s Albums: Photographs, Community and Identity,” in New Zealand Journal of History, 52, 1, 2018, p. 24 on the Academia website 2018 [Online] Cited 28/08/2024

3/ Jules Prown, ‘Mind in Matter: An Introduction to Material Culture Theory and Method’, Winterthur Portfolio, 17, 1 (1982), pp. 1-2 quoted in Haley, Op. cit., p. 24.

4/ Jarrod Hore. “Capturing Terra Incognita: Alfred Burton, ‘Maoridom’ and Wilderness in the King Country,” in Australian Historical Studies Volume 50, Issue 2, 2019, pp. 188-211 quoted in Professor Angela Wanhalla Op. cit.,

5/ Shaun Higgins, Auckland Museum pictures curator quoted in Sapeer Mayron. “A Different Light: A chance to see 19th-century Aotearoa as our first photographers saw it,” on The Post website April 7, 2024 [Online] Cited 28/06/2024.

6/ Professor Angela Wanhalla, Op. cit.,

7/ Joyce Campbell. “A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa,” on the New Zealand Review of Books website May 14, 2024 [Online] Cited 23/06/2024

Many thankx to the Auckland War Memorial Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“For Māori there was another dimension. The living connection to the sitter was the same as to a carved ancestor, or any other manifestation. Wharenui would eventually feature photographs of ancestors located where at one time they would have been depicted in other forms. But their presence has the same significance.” …

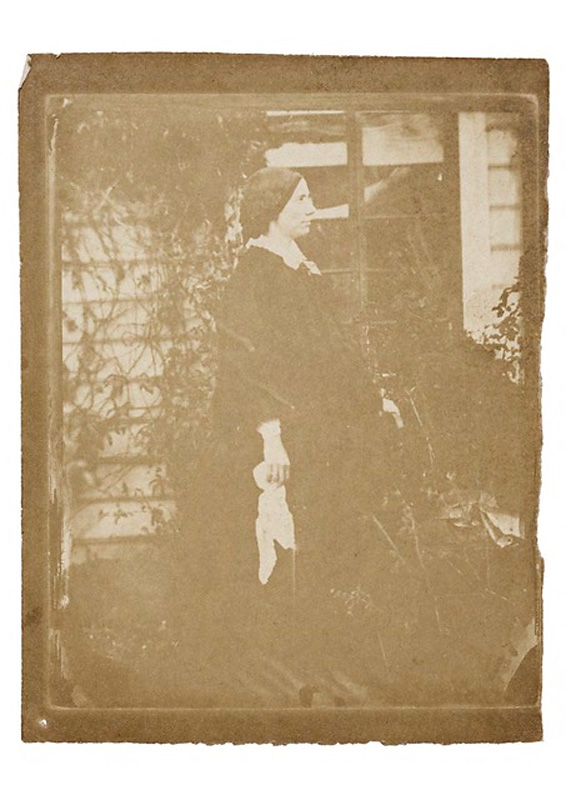

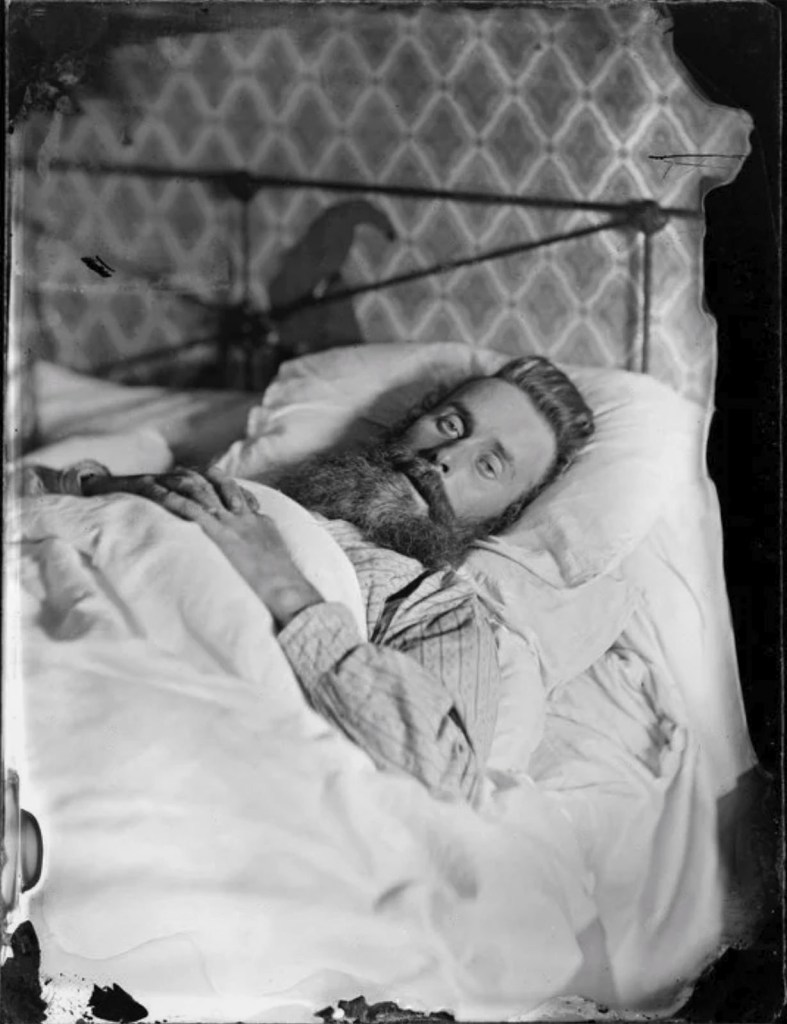

In Natalie Marshall’s essay ‘Camera Fiends and Snapshooters: Early Amateur Photography in Aotearoa’, it is the immediacy of photographs by James Coutts Crawford, Henry Wright and Robina Nicol that ‘pricks’ me, as Roland Barthes would have it. These photographers working far from the global centre of their craft are freed to explore domesticity and love. Their photographs are suffused with intimacy, warmth, pregnancy, yawning and easy comradery. It is easy to see that how they lived intersects with how we live now, and also to recognize the ways in which it does not. If these photographs are technically rough, or worn, we easily look past all that to engage with an image of another person or place. The images defy the notion that we need hyper-reality, immersion, massive scale, vivid colour or idealised beauty in order to achieve psychic proximity.

Joyce Campbell. “A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa,” on the New Zealand Review of Books website May 14, 2024 [Online] Cited 23/06/2024

A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa – from the curators

Hear from the curators of A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa, from from Auckland Museum, Hocken Collections, and Alexander Turnbull Library, as they speak to some of their favourite objects from this new exhibition that explores the captivating evolution of photography in 19th-century New Zealand.

Witness the dawn of photography in Aotearoa New Zealand. Through precious, original photographs, explore its beginnings as an expensive luxury, through to becoming a part of everyday life.

Step into A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa and explore the captivating evolution of photography in 19th-century New Zealand. Delve into the advances that took photography from its beginnings for an exclusive few in the mid-1800s, to being a part of daily life by the turn of the century.

Experience the 19th-century studio as you pose for your own digital Victorian portrait, and explore the wonder of this new technology that changed the way we see ourselves forever.

Featuring precious, original photographs from Auckland Museum, Hocken Collections, and Alexander Turnbull Library, this exhibition offers a unique glimpse into our visual heritage.

Text from the Auckland War Memorial Museum website

James Coutts Crawford (New Zealand born Scotland, 1817-1889)

Jessie Crawford, probably outside the Crawfords’ home in Thorndon, Wellington

c. 1859

Salted paper print

143 × 110 mm

Alexander Turnbull Library

A rare image of a heavily pregnant Victorian woman, shot outdoors in a domestic garden.

James Coutts Crawford (New Zealand born Scotland, 1817-1889)

Nurse Edgar [left] and Jessie Crawford

c. 1860

Salted paper print

Alexander Turnbull Library Collection

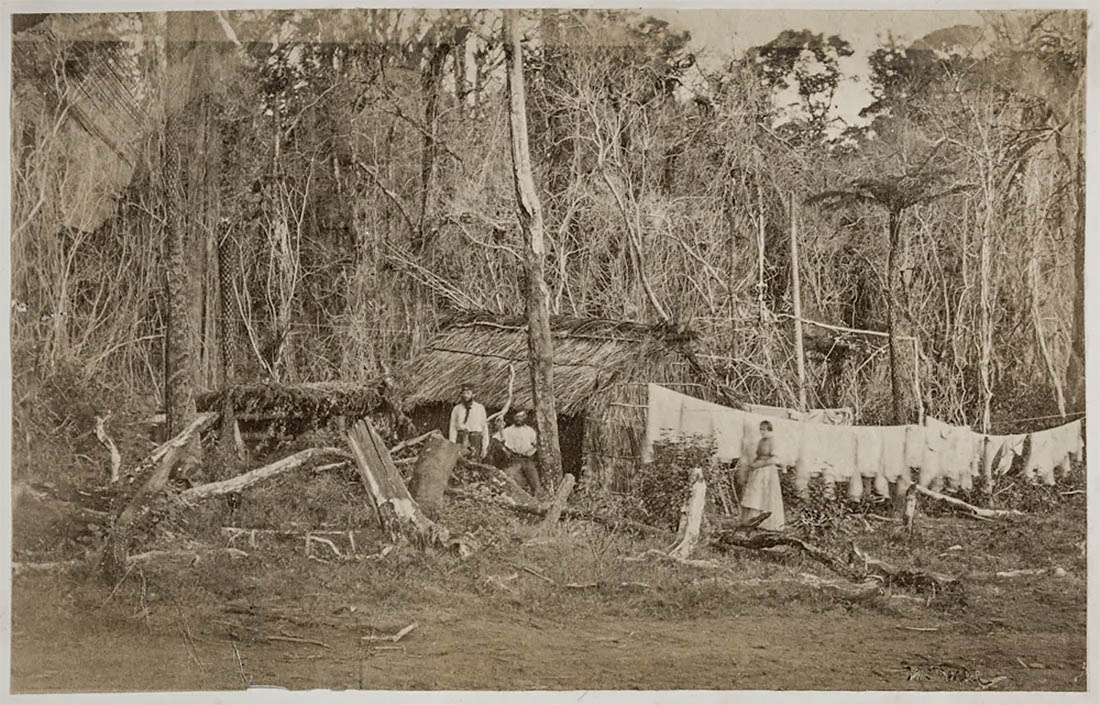

William Temple (New Zealand born Ireland, 1833-1919)

The Bush at Razorback, Great North Road New Zealand

1862-1863

Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum

Medical officer with Imperial forces during New Zealand Wars; photographer. Born Co Monaghan, Ireland, son of William Temple MD and Anne Temple. Entered army service 1858, and served as Assistant Surgeon with the Royal Artillery in the Taranaki (1860-1861) and Waikato (1863-1865) campaigns. He was awarded the Victoria Cross for gallantry at Rangiriri. Died in London.

Text from the National Library of New Zealand website

“… every single photograph is taken with purpose. The photographer chooses what’s in the frame. There is always a bit of an edit in that regard.

“When you’re documenting, you’re not this invisible entity that’s just documenting everything, you are making choices. You are, in effect, not documenting neutrally, but with your own agenda.”

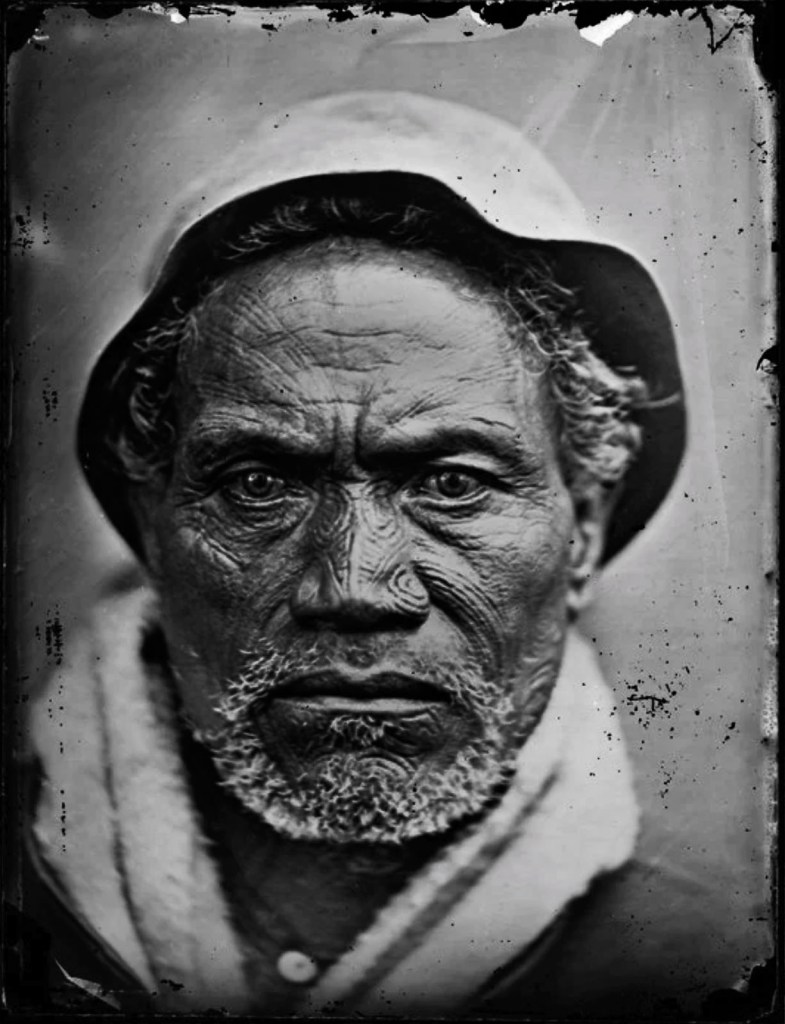

While many of the pictures have full captions detailing not only who took the photo but who is featured in it, some people’s names were lost – or possibly were never recorded at all, Higgins says.

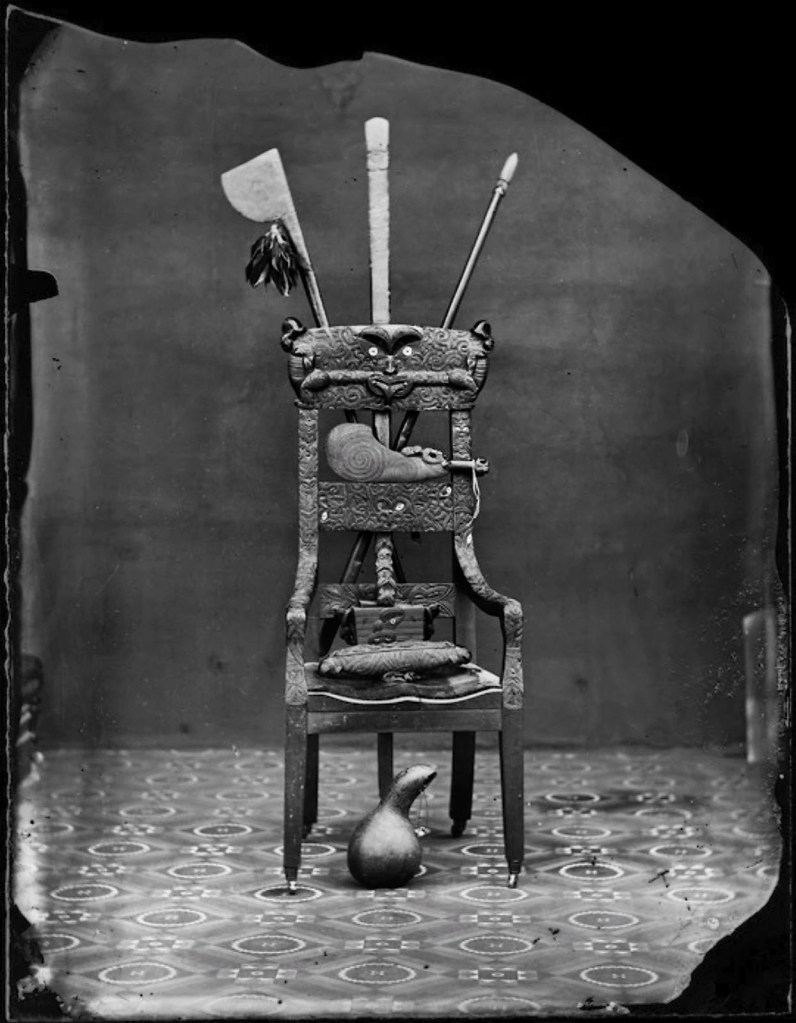

Māori in particular were often photographed and their names and identities not preserved, called instead “Māori celebrities” and dressed with props in the artists’ studios.

“Sadly we sometimes know the studio, but we don’t know who they are, we don’t know answers to questions why they were taken. Did you walk away with your own picture, but did you know that that would then be sold to collectors for their albums?

“You might see someone and say, ‘Oh, they’re sitting with their taonga’. Well, not necessarily, they might be sitting with the studio’s prop and dressed up for a certain image.

“Photos like these are why throughout the exhibition you might see the question: Do you know who is in this picture? Higgins hopes with a bit of luck, some of the “orphan pictures” with no names might be identified.

“Our own institution and others play a part. We collect from collectors and photos end up in an institution with no name,” Higgins says.

“The best thing we can do is put them out and say, ‘Do you know who these people are?’ and hopefully we find out more about these orphan photographs that have made their journey through time in albums collected by largely white men.

“We don’t have answers, but we can pose the questions. I hope people walk away from an exhibition like this questioning some of the things they’ve seen and maybe looking at things in a different light.”

Shaun Higgins, Auckland Museum pictures curator quoted in Sapeer Mayron. “A Different Light: A chance to see 19th-century Aotearoa as our first photographers saw it,” on The Post website April 7, 2024 [Online] Cited 28/06/2024.

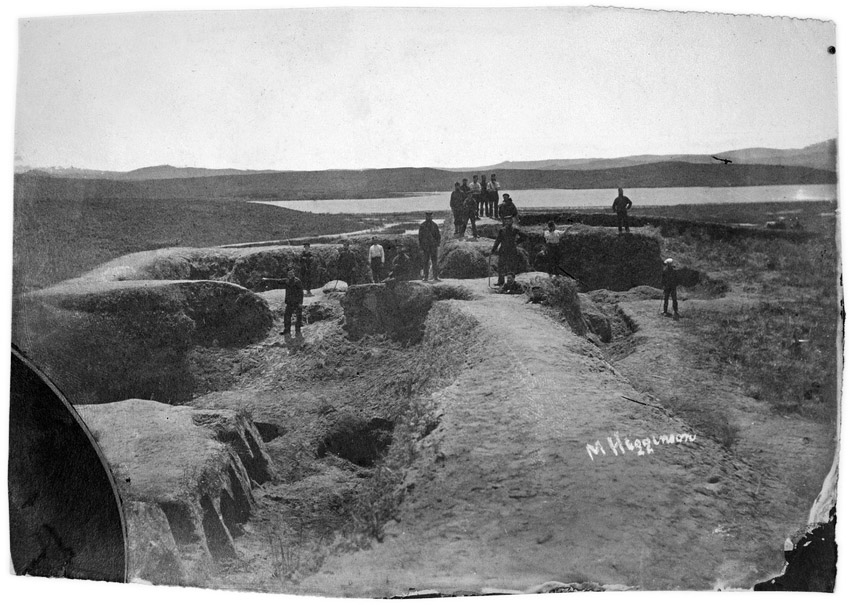

Montagu Higginson (English, 1840-1910)

The Native Earthworks at Rangiriri partially destroyed

November 1863

Auckland Museum

In 2006 Auckland Museum acquired the album Photographs of the South Sea Islands; a photograph album featuring the work of a hitherto unknown photographer, one George Montagu John Higginson (Auckland War Memorial Museum 2006:28). Known commonly as Montagu Higginson (Illustrated London News vol. 045 XLV:91), this amateur photographer produced many images of the Waikato campaign that are either new, or at the very least previously of unknown authorship. There are also many images which cross over to other albums compiled by other photographers indicating the strong possibility of trading. This notion has been considered by Main and Turner (1993:10) with regard to other photographers such as Daniel Manders Beere.

Shaun Higgins. “Brothers in Glass: Montage Higginson and the Photographers of the Waikato War,” Auckland Museum Records, 2012

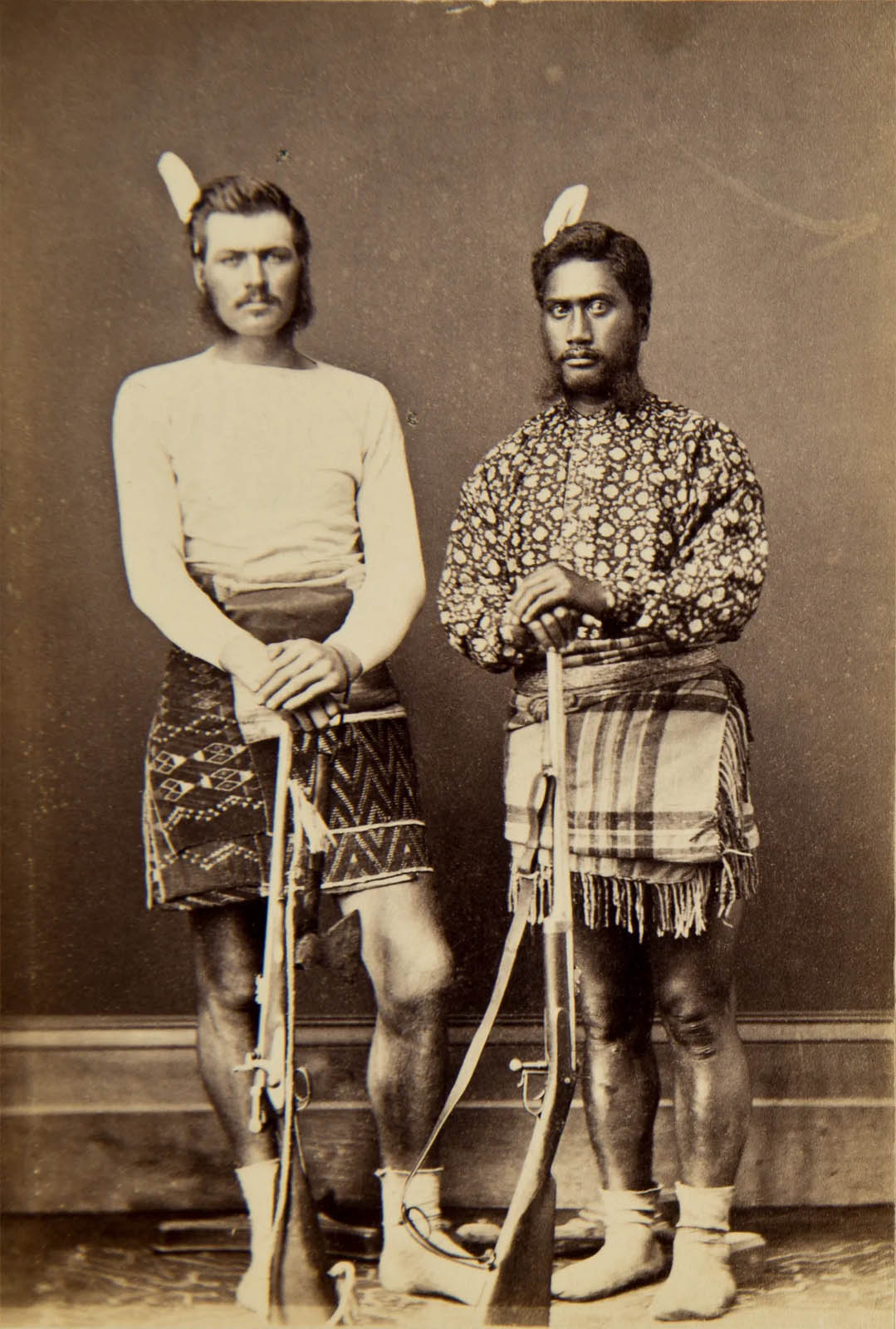

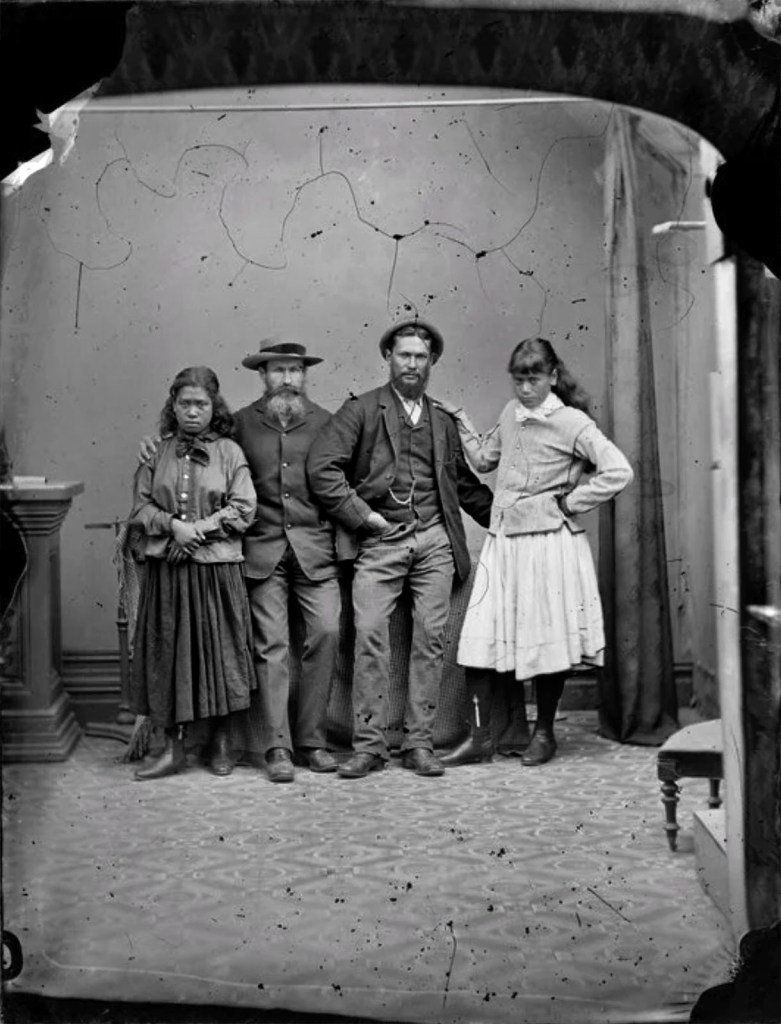

Batt & Richards (firm) (finished January 1874)

Tom Adamson and Wiremu Mutumutu, Wanganui

c. 1867-1874

Hocken

This studio carte de visite provides striking evidence of cultural exchange in the way of Māori and European fabrics and designs, with Tom Adamson on the left wearing a woven flax kaitaka with a geometric tāniko border, and Wiremu Mutumutu on the right wearing a fringed tartan rug, both in the manner of kilts. Adamson worked alongside Māori as a military scout and guide, hunting down dissidents in the dense native bush for pro-government forces during the New Zealand Wars. This service earned him a New Zealand Cross in 1876.

John McGregor (New Zealand born Scotland, 1831-1894)

Bell Hill

c. 1875

Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena

Photographer, Stuart St, Dunedin, fl 1863-1884. Awarded first class certificate at The New Zealand Exhibition 1865 (Source: Photography in New Zealand / Hardwicke Knight and back of photograph). Died 12 Oct 1894, aged 63 years. 32 years in New Zealand, formerly of Glasgow, Scotland. Buried at Southern Cemetery, Dunedin (Source: Dunedin online cemetery database).

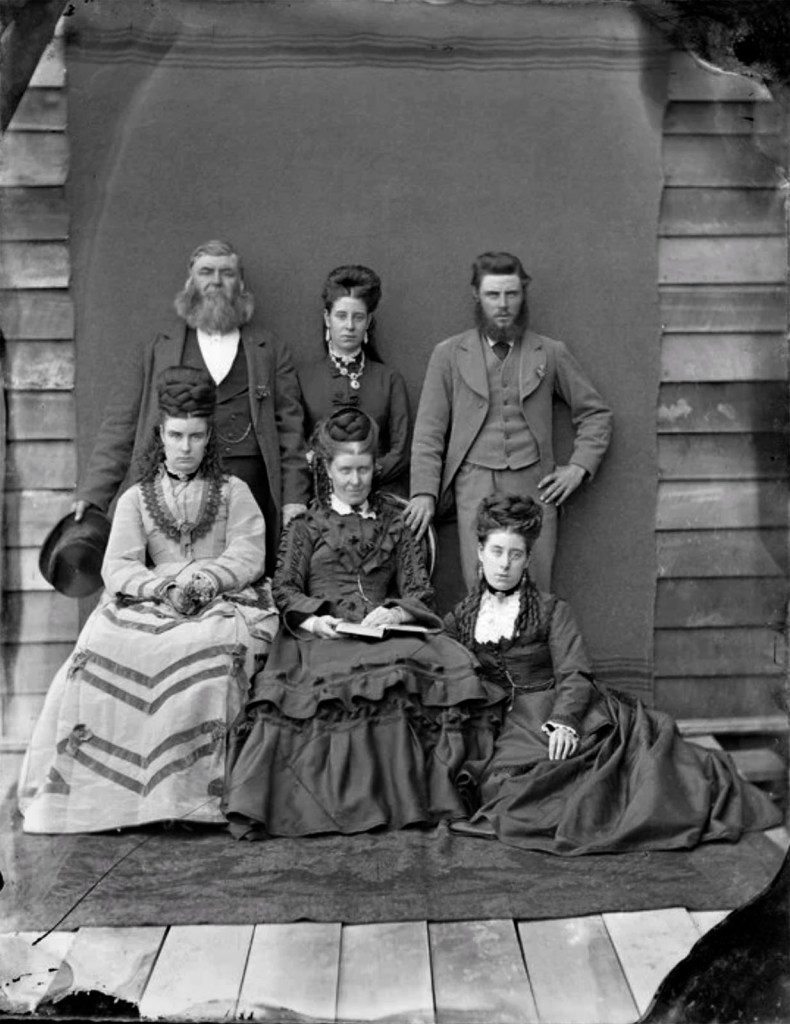

In 1848, two decades after a French inventor mixed daylight with a cocktail of chemicals to fix the view outside his window onto a metal plate, photography arrived in Aotearoa. How did these ‘portraits in a machine’ reveal Māori and Pākehā to themselves and to each other? Were the first photographs ‘a good likeness’ or were they tricksters? What stories do they capture of the changing landscape of Aotearoa?

From horses laden with mammoth photographic plates in the 1870s to the arrival of the Kodak in the late 1880s, New Zealand’s first photographs reveal Kīngi and governors, geysers and slums, battles and parties. They freeze faces in formal studio portraits and stumble into the intimacy of backyards, gardens and homes.

A Different Light brings together the extraordinary and extensive photographic collections of three major research libraries – Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum, Alexander Turnbull Library and Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena – to coincide with a touring exhibition of some of the earliest known photographs of Aotearoa.

Text from the Auckland War Memorial Museum website

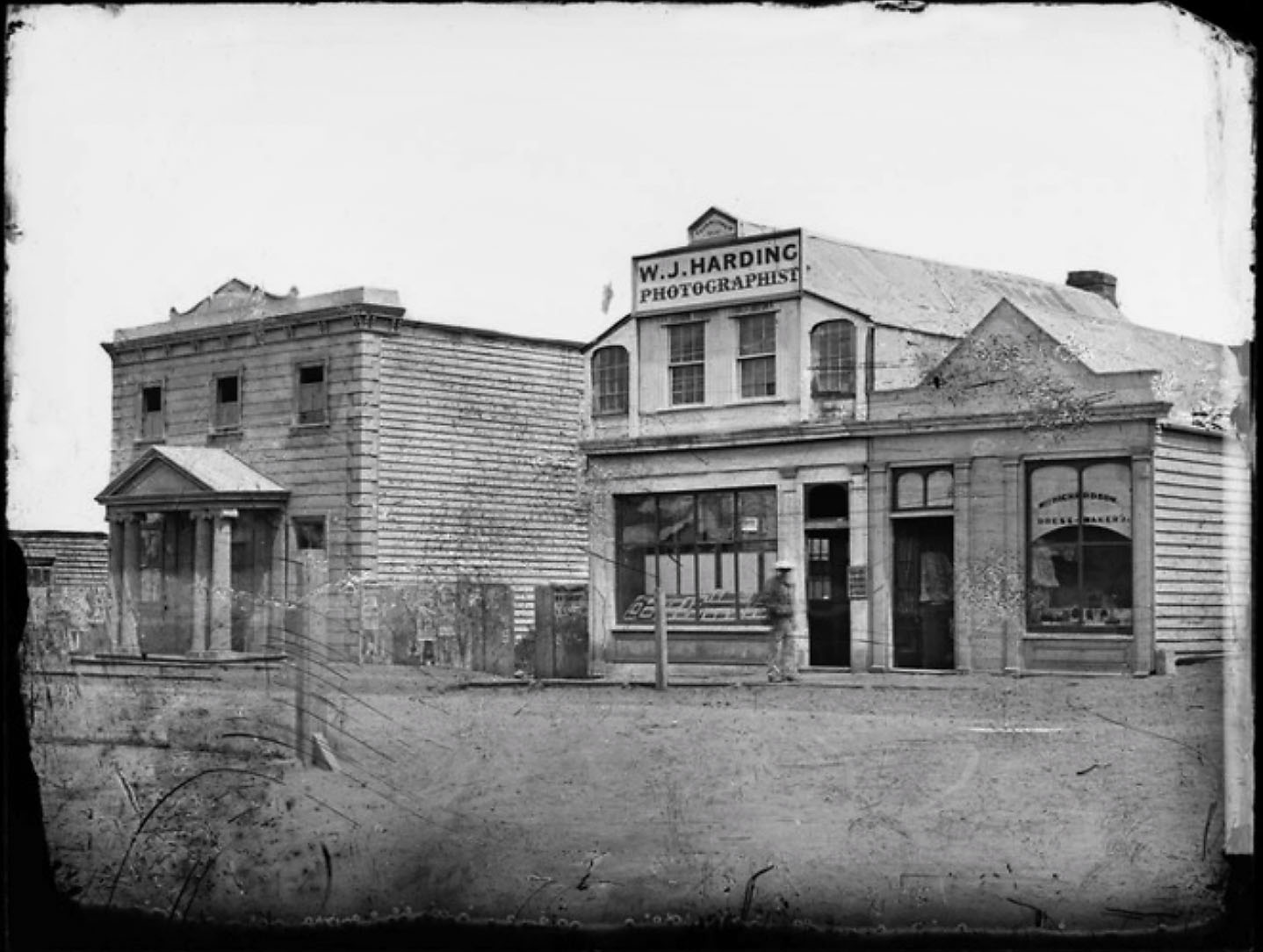

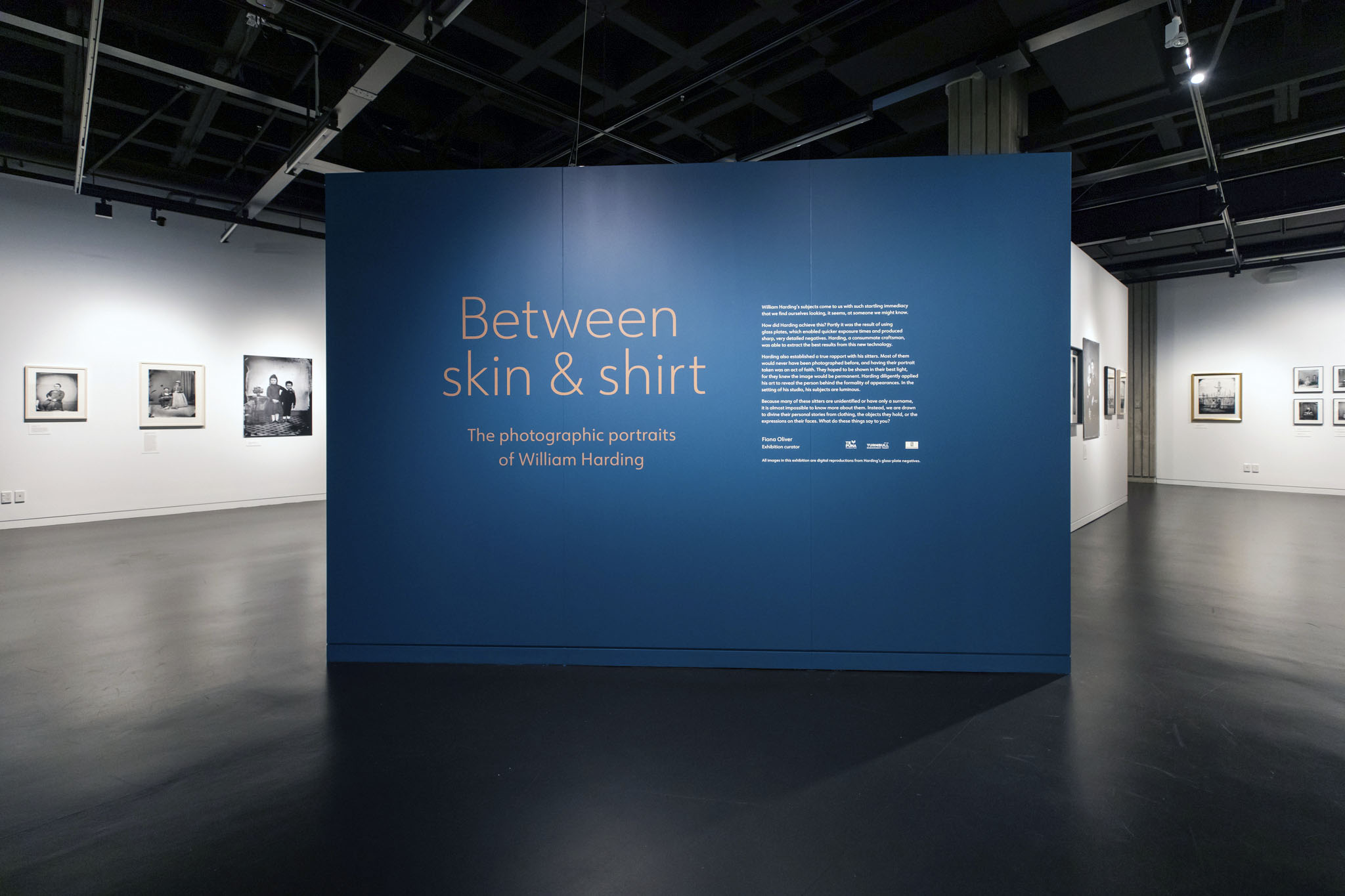

William James Harding (New Zealand born England, 1826-1899)

Young woman looking at photograph album

c. 1870s

Quarter-plate collodion silver glass negative

Alexander Turnbull Library Collection

William and Annie Harding arrived in New Zealand in 1855. Two brothers had already emigrated – John in 1842 and Thomas in 1848. The three brothers, and Annie, were followers of Emanuel Swedenborg, and strong supporters of the Total Abstinence Society. William and Annie settled in Wanganui, where William set up briefly as a cabinet-maker but in 1856 established a photographic studio. By the 1860s his studio was installed in a two-storeyed, corrugated-iron building on Ridgway Street.

Text from the Wikipedia website

William James Harding founded his studio in Wanganui in 1856. In 1889 he sold it to Alfred Martin, who had previously practiced in Christchurch. During his tenure, Harding occasionally hired out his studio to other photographers, and there are images in the 1/4 plate sequence which the Library also holds as cartes-de-visite by the photographers D Thomson and T Tuffin. Alfred Martin sold the business to Frank Denton in 1899. Denton in turn sold out to Mark Lampe around 1930, but retained Harding’s negatives, and Martin’s 10 x 8 and 10 x 12 negatives, himself.

Text from the National Library of New Zealand website

William James Harding (New Zealand born England, 1826-1899)

Studio portrait of a woman and child

1870s

Reproduction from quarter-plate collodion silver glass negative

Alexander Turnbull Library Collection

William James Harding (New Zealand born England, 1826-1899)

Captain Nathaniel Flowers and wife Margaret, with a dog

February 1878

Glass negative

4.25 x 3.25 inches

Negatives of Wanganui district

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand

When Nathaniel and Margaret Flowers visited the Whanganui photographic studio of W.J. Harding (1826-99) in February 1878, they engaged with a technology that was only a few decades old but one that had been rapidly embraced by ordinary people such as themselves. By the 1870s, people – as individuals, couples and families – could have their likenesses made for a small fee. Harding photographed people from an array of backgrounds, from social elites to imperial and colonial soldiers, as we as interracial couples such as Nathaniel and Margaret. As soon as photography was invented, it was used by individuals, families and communities to fashion their social identities around age, class, ethnicity and gender. It was quickly integrated into society through social and cultural practices such as the making and keeping of photograph albums.

Text from the Introduction to the book A Different Light – First Photographs of Aotearoa

Elizabeth Pulman (New Zealand born England, 1836-1900)

King Tāwhiao

1882

Carte de visite

Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum

Blackman, Elizabeth, 1836-1900, Chadd, Elizabeth, 1836-1900 Auckland photographer. Married George Pulman (d. 1871). Worked with him in his photographic studio in Shortland Street, specialising in scenic photographs and portraits. Elizabeth continued Pulman’s Photographic Studio for almost 30 years until the business was sold shortly before her death in 1900. After George Pulman’s death she married John Blackman (d 1893). She continued to be known professionally as Elizabeth Pulman.

Text from the National Library of New Zealand website

In the early years of photography it was relatively uncommon for women to take photographs, let alone work as professional photographers. Elizabeth Pulman was quite possibly New Zealand’s first female professional photographer.

Born in Lymm, Cheshire, England in 1836, she married George Pulman in 1859, and emigrated to New Zealand in 1861. Although a joiner and draughtsman by training, in 1867 George Pulman opened a photographic studio in Auckland, specialising in scenic photographs and portraits. Elizabeth assisted George with the business and after he died in 1871 she continued the work of the studio.

She married John Blackman in 1875, and was once more widowed in 1893. But for almost 30 years, until the business was sold to the Government Tourist Bureau shortly before her death, she carried on Pulman’s Photographic Studio, almost single-handedly managing the upbringing of nine children, running a successful business, and the problems of a period of rapidly changing technology in photography.

Pulman’s Photographic Studio left a legacy of many prints of historical interest, in both portrait and scenic subjects. Among the portraits are photographs of many important Maori chiefs of the North Island, including Tawhiao, the second Maori King, taken in Auckland shortly after he left his King Country stronghold.

Adapted by Andy Palmer from the DNZB biography by Phillip D. Jackson published as “Elizabeth Pulman,” on the New Zealand History website updated

John Martin Hawkins Lush (New Zealand, 1854-1893)

Picnic party at Thames

c. 1884

Half-plate gelatin silver glass negative

Auckland Museum Collection

Unknown photographer

Three men in hats

c. 1880s

Ferrotype

Hocken Collections

Charles Spencer (New Zealand born England, 1854-1933)

Cold Water Baths White Terrace

c. 1880s

Cyanotype

Auckland Museum Collection

New Zealand photographer operating in Tauranga from 1879. Active in Auckland from the 1880s to 1917. Was one of Stephenson Percy Smith’s survey party at Mount Tarawera after the 1886 eruption. Took a series of photographs on White Island in late 1890s.

For more information on the photographer see Charles Spencer, Photographer (Part I) May 2019 and Charles Spencer, Photographer (Part II) July 2019 on the Tauranga Historical Society website

Josiah Martin (New Zealand born England, 1843-1916)

Portrait of an unidentified sitter from the Teutenberg family album

c. 1880s

Albumen silver print, cabinet card

Auckland Museum Collection

Josiah Martin was born in London, England, on 1 August 1843 and, in 1864, married Caroline Mary Wakefield. They emigrated to New Zealand a few years later with an infant daughter and eventually settled in Auckland. Martin founded a private academy, where he was headmaster until 1874 and proved to be a gifted teacher but retired from the profession in 1879 due to failing health.

He then concentrated on photography. During 1879 he returned to Europe, and while in London studied the latest innovations in photographic techniques and processes. On his return to Auckland he opened a photographic business with a studio on the corner of Queen and Grey streets in partnership with W.H.T. Partington. After the partnership was dissolved he opened another studio in Queen Street, later selling the portrait business and transferring premises to Victoria Arcade. Martin visited the area of Tarawera and Rotomahana many times and was there on the eve of the eruption of Mt Tarawera in 1886; some of the photographs he took after the eruption were reproduced in the Auckland Evening Star. He also appears to have visited several Pacific Islands, including Fiji and Samoa, in 1898, and in 1901 travelled there with S. Percy Smith. He published an account of this trip in Sharland’s New Zealand Photographer and also contributed articles and photographs to the Auckland Weekly News and the New Zealand Illustrated Magazine.

Martin gained an international reputation for his ethnological and topographical photographs. His work was exhibited in London at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 and he won a gold medal at the Exposition coloniale in Paris in 1889. He was also editor of Sharland’s New Zealand Photographer for several years and lectured frequently, not only on photography but also on scientific subjects.

Josiah Martin died on 29 September 1916 at his home in Northcote, Auckland, aged 73. His photographs provide a record of changed landscapes and societies. Martin was one of the first photographers to realise the commercial potential of photography to encourage tourism, but he was also aware of the need for conservation of the landscape and of the role of photography in providing a documentary record (Orange 1993, pp.313-314).

Orange, Claudia ed. (1993), The dictionary of New Zealand biography, volume 2, 1870-1900, Wellington: Bridget Williams Books Limited and the Department of Internal Affairs.

Harriet Cobb (New Zealand born England, 1846-1929)

Two wāhine

c. 1887-1890

Albumen silver print, carte de visite

Alexander Turnbull Library Collection

The word “wahine” came into English in the late 18th century from Maori, the language of a Polynesian people native to New Zealand; it was originally used for a Maori woman, especially a wife. The word is also used for a woman in Hawaiian and Tahitian, though spelled “vahine” in the latter.

Harriet Sophia Cobb (née Day, 10 February 1846 – 18 December 1929) was a New Zealand photographer. Her works are held in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Cobb operated two successful photography studios in the late 1800s and into the 20th century.

In 1866 she married Joseph Edward Cobb, and they went on to have 15 children… In 1884 Cobb and her husband emigrated from the United Kingdom to New Zealand with their nine children and set up a photographic studio in the Hawke’s Bay. They arrived in Wellington on the Lady Jocelyn.

The couple operated two studios known as JE & H Cobb in Napier (from 1884) and Hastings (from 1885), but in 1887 after Joseph’s bankruptcy, Cobb won a plea to operate the businesses in her name until she retired in 1911… Cobb died on 18 December 1929 in Ōtāhuhu, Auckland.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Ambitious and creative

Harriet was a busy and ambitious woman – having a sensibility for the photographic trade learnt from her father that was out of step in the sleepy colony of New Zealand. Her work in the 1885 Industrial Exhibition in Wellington caught the attention of Julius von Haast who selected it for inclusion in the New Zealand court at the 1886 Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London.

Cobb’s work was described by a reviewer as being portraiture of mostly female subjects. By being included in the exhibition, Cobb’s work inserted the visual existence of family life and women’s lives in the colony into the multitude of industrial and scenic exhibits that dominated the New Zealand court at the London exhibition.

An art photographer

Cobb advertised herself as an ‘art photographer’, which was a way of claiming that her work was of higher quality than other photographers. In one of Cobb’s advertisements she claimed that the basics of photography could be learnt by any school boy in a week but not the skills, experience, and eye for creating quality photographs that she had.

Cobb’s marketing targeted a broad clientele and emphasised quality service in a quality establishment run by herself. She wanted it understood that her studios were respectable places for women to go unaccompanied by men.

Extract from Lissa Mitchell. “Inspiring stories about NZ women photographers – Harriet Cobb (1846-1929),” on the Museum of New Zealand / Te Papa Tongarewa website 16 Oct 2018 [Online] Cited 10/08/2024

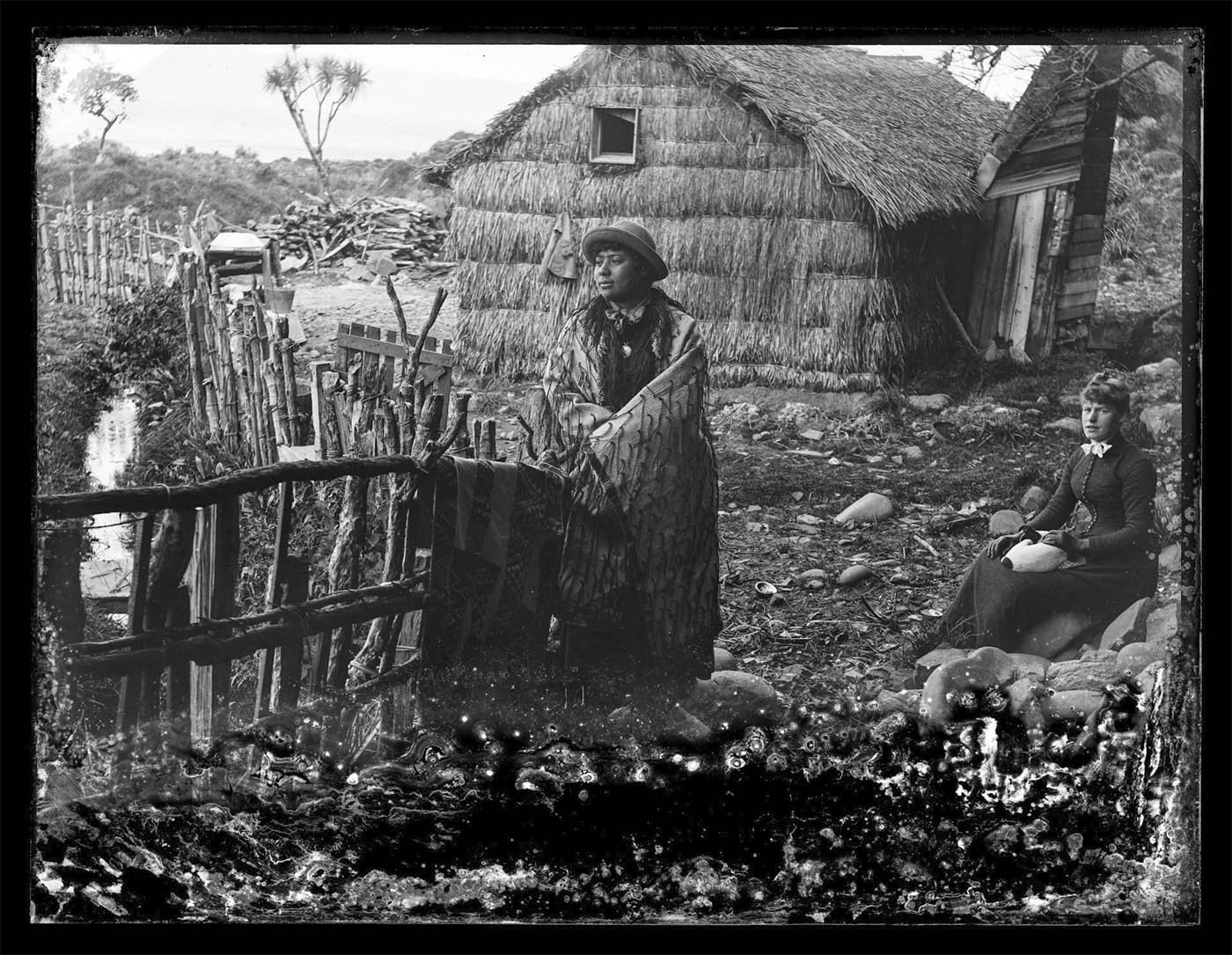

Henry Wright (New Zealand, 1844-1936)

Māori woman in a tag cloak (possibly Rīpeka Te Puni) and Amy Elizabeth Wright, Wellington

c. 1885

Alexander Turnbull Library

John Kinder (New Zealand born England, 1819-1903)

Mount Tarawera

1886

Albumen silver print mounted on album page

151 × 200 mm

Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum

While he [Kinder] was at Ayr Street Kinder also practised as an amateur photographer. There is no indication that he had taken an active interest in photography in England. Rather, it seems likely that he learned the wet-plate photographic process in Auckland about 1860-61. He was friendly with Hartley Webster, a prominent professional, who was the Kinder family photographer in the 1860s. He also collected prints of the work of Daniel Manders Beere, a photographer working in Auckland at the same time, whose photography has some affinities with his own.

Kinder was primarily a landscape and architectural photographer, although he did take a few portraits of family and friends, including Celia Kinder and the Reverend Vicesimus Lush, vicar of Howick. One of his best-known photographs is the portrait of Wiremu Tāmihana, which was used as the frontispiece for John Gorst’s The Māori King (1864). There are also a few fine photographs of Māori artefacts, including canoes and canoe prows. He took photographs of Parnell in the 1860s, especially of Anglican buildings such as the first St Mary’s Church, St Stephen’s Chapel and Bishopscourt (Selwyn Court). These provide a good historical record as well as having high artistic merit. Kinder also travelled extensively and his paintings and photographs are not confined to Auckland. After his sisters Mary and Sarah settled in Dunedin in 1878 he made several trips to the South Island.

In his photographs and paintings Kinder imposed a sense of order on his views, as if regulating them to current conventions of composition where clarity and intelligibility were paramount. This tidiness, combined with the serene calmness of the depicted weather conditions, can give a Utopian or idealised dimension to his colonial scenes. While there is a high degree of objectivity in his works, this does not exclude an element of interpretation – an adaptation of landforms and buildings to an ideal. His art expresses a positive view of the colonising process. It is worth noting that many of his finished paintings were made late in life, during his retirement, when he was looking back through rose-tinted glasses to a time of great achievement and rapid progress. In an unpublished autobiography, written in his later years, he recalled with pride how the city of Auckland had grown from the humble beginnings he encountered in 1855, when there were only one or two decent buildings to be seen.

Extract from Michael Dunn. “Kinder, John,” first published in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography in 1993 digitally published on the Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand website [Online] Cite 11/08/2024

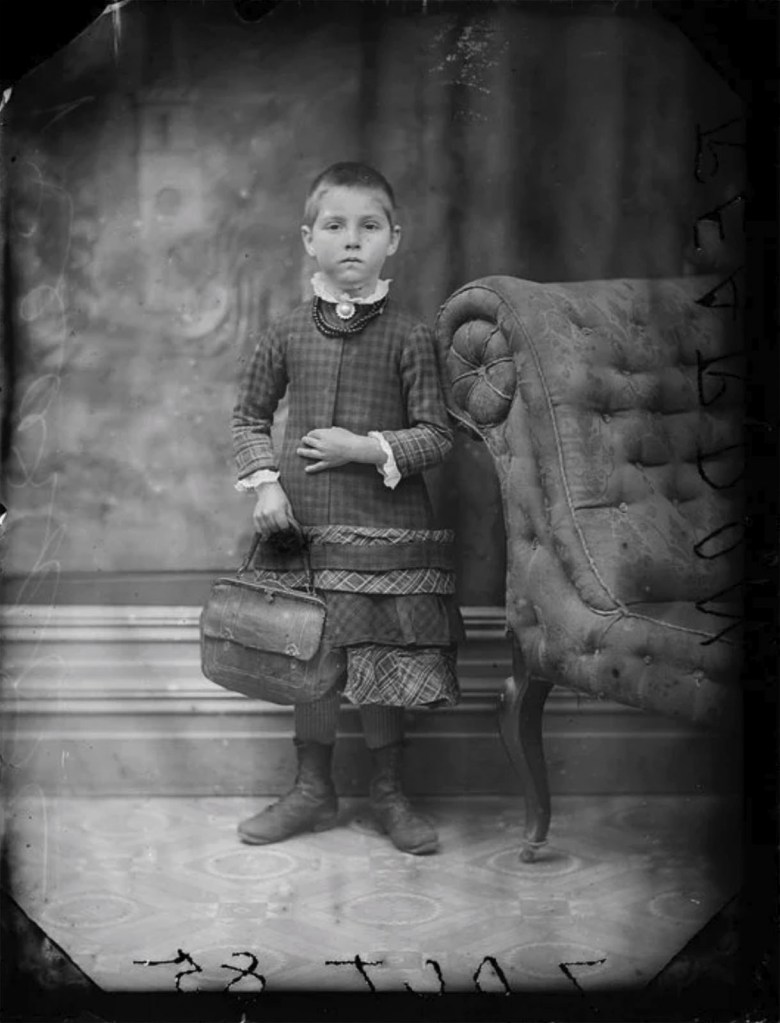

Unknown photographer

Portrait of an unidentified child

c. 1890

Crystoleum

Auckland Museum Collection

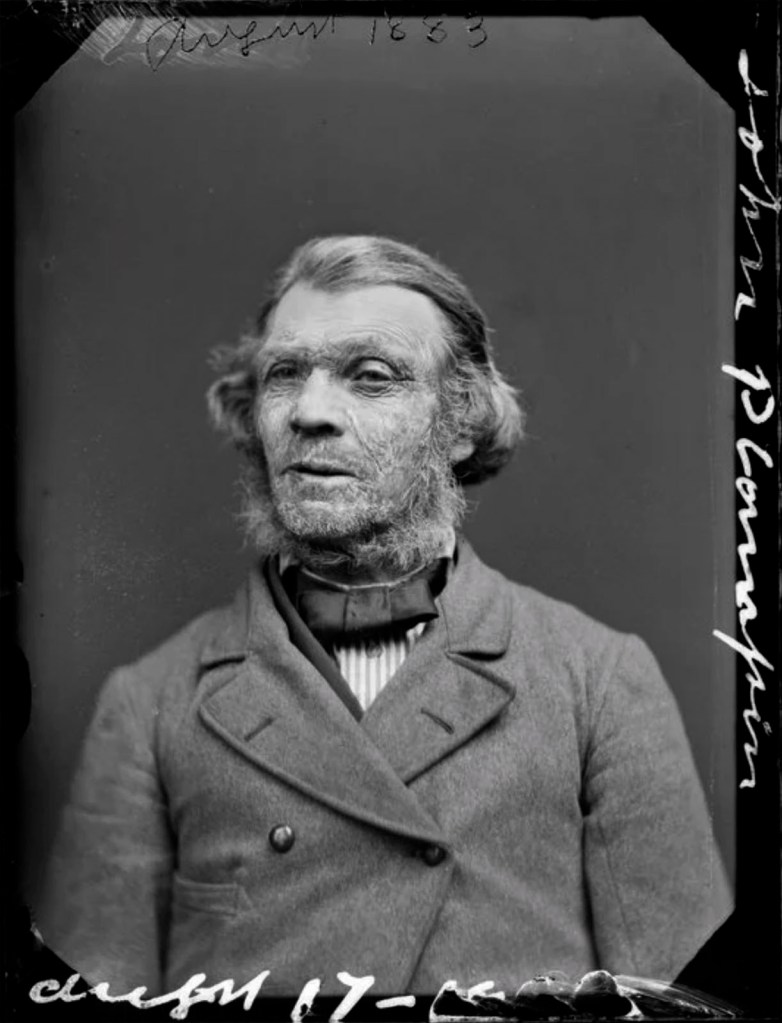

Elite Photographers

Portrait of the Thompson family, with drawn-on eyes and eyebrows

1893

Opalotype

Auckland Museum Collection

The settler lens

Photographs are complicit in colonialism because they were used to document the impacts of migration, settlement and land transformation. For example, they illustrate the advance of settlement and the subjugation of Māori after the Waikato War (1863-1864).

Imperial officers such as William Temple, who was active in military campaigns to advance European settlement, photographed two icons of colonisation: roads and military camps.

An Irish-born soldier, Temple followed the Great South Road on foot and with his camera as the route advanced towards the border of Kiingitanga territory. One of his photographs (The Bush at Razorback, Great North Road New Zealand, 1862-1863) demonstrates the impacts of the Great South Road on the local environment.

Photography’s commercial interests also aligned with colonial propaganda, especially as landscape photography grew in popularity from the 1870s. Historian Jarrod Hore has demonstrated how landscape photographers helped shape settler attitudes to the environment, but also documented colonial progress.

Photographs were used to illustrate engineering successes and the advancing tide of settlement. For instance, John McGregor’s 1875 photograph (Bell Hill, c. 1875) depicts the clearing of Bell Hill in Dunedin. In the background, the church embodies the possibilities of colonial advancement enabled by environmental transformation.

Our early photographers were, in Hore’s words, engaged in “settler colonial work” because they “mobilised and visually reorganised local environments in the service of broader settler colonial imperatives.”

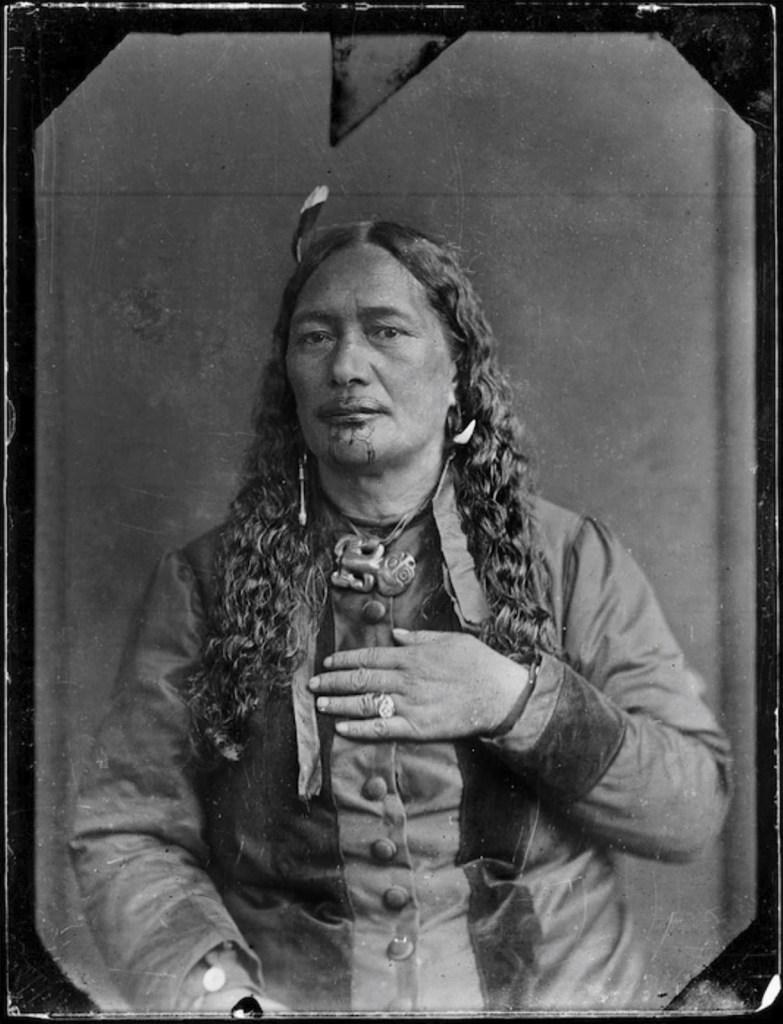

The photograph as taonga

Indigenous peoples were a particular focus of early photography in other settler colonial societies. New Zealand followed this pattern and Māori feature prominently in our colonial photographic record.

As soon as photography arrived in the colony, Māori were captured by the camera. Itinerant daguerreotype photographers travelled the new colony in the 1840s and 1850s to exploit the commercial opportunities available in new colonies such as New Zealand.

Reproduction of colonial tropes became common in commercial photography, reflecting the collectability of Māori as photographic subjects. The carte-de-visite, popular from the 1860s and of a size that could easily be posted, meant images of Māori found their way into albums all around the world.

Such images became an important part of the business for studio photographers in the colonial period.

At different times, and depending on the context, Māori embraced or rejected photography. Because of its colonial implications, Māori whānau and communities have a complicated relationship with the camera. But, as scholars Ngarino Ellis and Natalie Robertson argue, there is evidence it was regarded as friend as much as foe.

Māori have long integrated visual likenesses into customary practices, such as tangihanga (funerals), while portraits adorn the walls of wharenui [meeting house, large house] across the country.

Colonial photographs are culturally dynamic. Their integration into Māori life means they do not just depict relationships but are imbued with them. As such, photographs are taonga (treasures) and connect people across time and space.

Te Whiti and the camera

Māori also took up the camera. Canon Hākaraia Pāhewa, for instance, was a skilled photographer who took his camera on his pastoral rounds, during which he recorded scenes of daily life.

He depicted people at work and documented transformations of landscapes, important cultural events, religious service and domestic routines. These photographs bring to light the diversity and richness of Māori life in the early 20th century.

Māori whānau [basic extended family group] already valued and used photographs in a variety of ways in the 19th century. Photographs were memory containers, mementos of family, markers of personal transformation, and generators of social connection.

Designed to be shared and displayed, photographs were prompts for discussion and storytelling. They are visual records of whakapapa [Whakapapa is a fundamental principle in Māori culture. Reciting one’s whakapapa proclaims one’s Māori identity, places oneself in a wider context, and links oneself to land and tribal groupings and their mana], identity and notions of belonging. They also mark Indigenous presence and survival in the face of settler colonialism.

At the same time, though, photography’s role in advancing colonialism meant Māori were cautious about the reproduction of images. There was an awareness of what could happen to photographs once they were out of the subject’s control.

Extract from Professor Angela Wanhalla. “The past in a different light: how Māori embraced – and rejected – the colonial camera lens,” on The Conversation website April 11, 2024 [Online] Cited 10/08/2024

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Henry Wright (New Zealand, 1844-1936)

Rahui Te Kiri Tenetahi [right] and her daughter Ngāpeka Te Roa of

Ngāti Manuhiri

1893

Full-plate gelatin silver glass negative

216 × 165 mm

Alexander Turnbull Library

Rahui Te Kiri Tenetahi (right) and her daughter Ngapeka Te Roa, of Ngati Manuhiri, alongside a building made of ponga logs, Little Barrier Island, 1893. They hold dahlia flowers.

Henry Wright was a prominent Wellington businessman. He was also a keen amateur photographer. Negatives found in two wooden boxes under house at 117 Mein Street, originally the home of Henry Wright, who had lived there from 1896 until his death in 1936.

Henry Wright spent nearly three months living on the island and produced a report for the government on its value as a bird reserve. After the government purchased the island from iwi and it was declared a forest reserve and bird sanctuary, Wright was appointed its first ranger. Wright’s series of photographs capture the vegetation, coastline and the last of the mana whenua [the right of a Maori tribe to manage a particular area of land], Ngāti Manuhiri, to live and sustain themselves on the island, including Rāhui Te Kiri Tenetahi, her daughter Ngāpeka Te Roa, and her second husband Wiremu Tenetahi, who were forcibly evicted just three years after Wright had visited the island.

Text from the book A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa

John Robert Hanna (New Zealand born Ireland, 1850-1915)

Portrait of unidentified sitters

c. 1895

Gelatin silver print, cabinet card

Auckland Museum Collection

Photographer of Auckland. Born Ireland in 1850, eldest son of Eliza Crawford and Robert Hanna of Drum, County Monaghan, Ireland; arrived in Auckland per ‘Ganges’ in 1865; began his photographic career in Auckland with R H Bartlett whose business he managed for some time. Then managed the firm of Hemus & Hanna for 10 years before business dissolved in 1885. Bought the business of J Crombie (which had been established in 1855) in Queen Street. Died in 1915.

Text from the National Library of New Zealand website

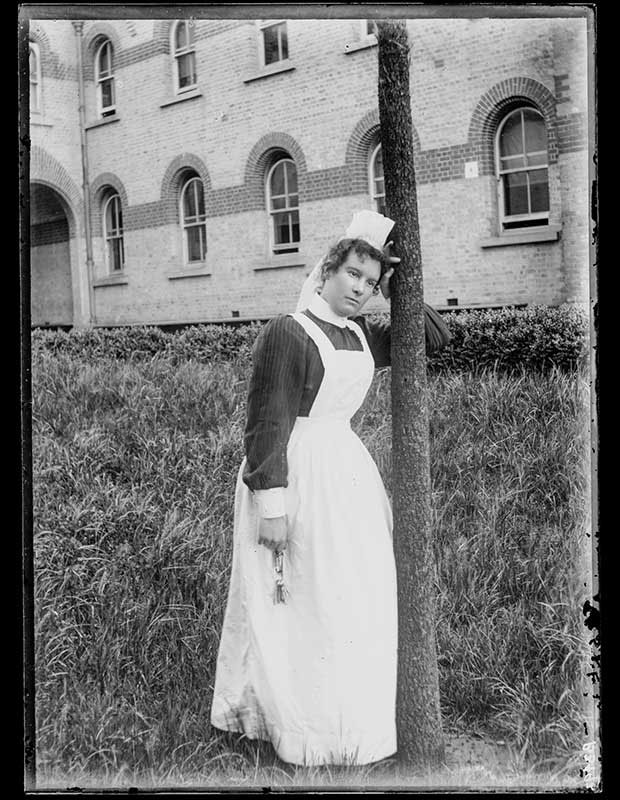

Margaret Matilda White (New Zealand born Northern Ireland, 1868-1910)

Nurse Pierce and Bessie McKay smoking with Mr Hodson and other nurses at Huia Private Hospital

1895

Gelatin silver print

Auckland Museum Collection

Margaret Matilda White

Margaret Matilda White came to New Zealand in the 1880s to join her family when she was 18 years old. She was acquainted with the photographer Hanna, possibly working in his studio. She established her own photographic business, which was not a success, but continued to photograph on an amateur or semi-professional basis until her early death in 1910.

Margaret Matilda White is best known for her photographs of the Auckland Mental Hospital, known at times as the Whau Lunatic Asylum, Oakley Mental Hospital or Carrington Mental Hospital. She photographed the buildings and the staff, making pictures of nurses and attendants with her characteristic structured group poses.

The Museum has a large collection of her glass plates, donated by her son Albert Sherlock Reed, in 1965.

Text from the Auckland Museum website

Margaret Matilda White (New Zealand born Northern Ireland, 1868-1910)

Self Portrait

c. 1897

Half-plate gelatin silver glass negative

164 × 120 mm

Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum

A series of photographs taken around 1897 by Margaret Matilda White (1868-1910) at the Whau Lunatic Asylum, also known as the Avondale Asylum, show a rare example of what appear as deliberately staged images of staff in the grounds. Starting as an apprentice to Hanna in 1890, White briefly operated a studio in Queen Street. She spent some time working as an attendant at the asylum, photographing the staff on location using a dry-plate camera. The playful approach White takes shows an unexpected side to her sitters, despite their formal uniforms. Arranged in the grounds, sitting together for a portrait, the men and women who worked at the asylum appear to have shed the formality of the studio. Even when they appear lined up in rows, they all look in different directions as a man peers through the window behind them. One image, thought to be a self-portrait, shows White in her uniform holding a set of keys. An informal portrait taken at Huia Private Hospital shows staff smoking together on a break: a far cry from the wooden poses of early likenesses.

Text from the book A Different Light: First Photographs of Aotearoa

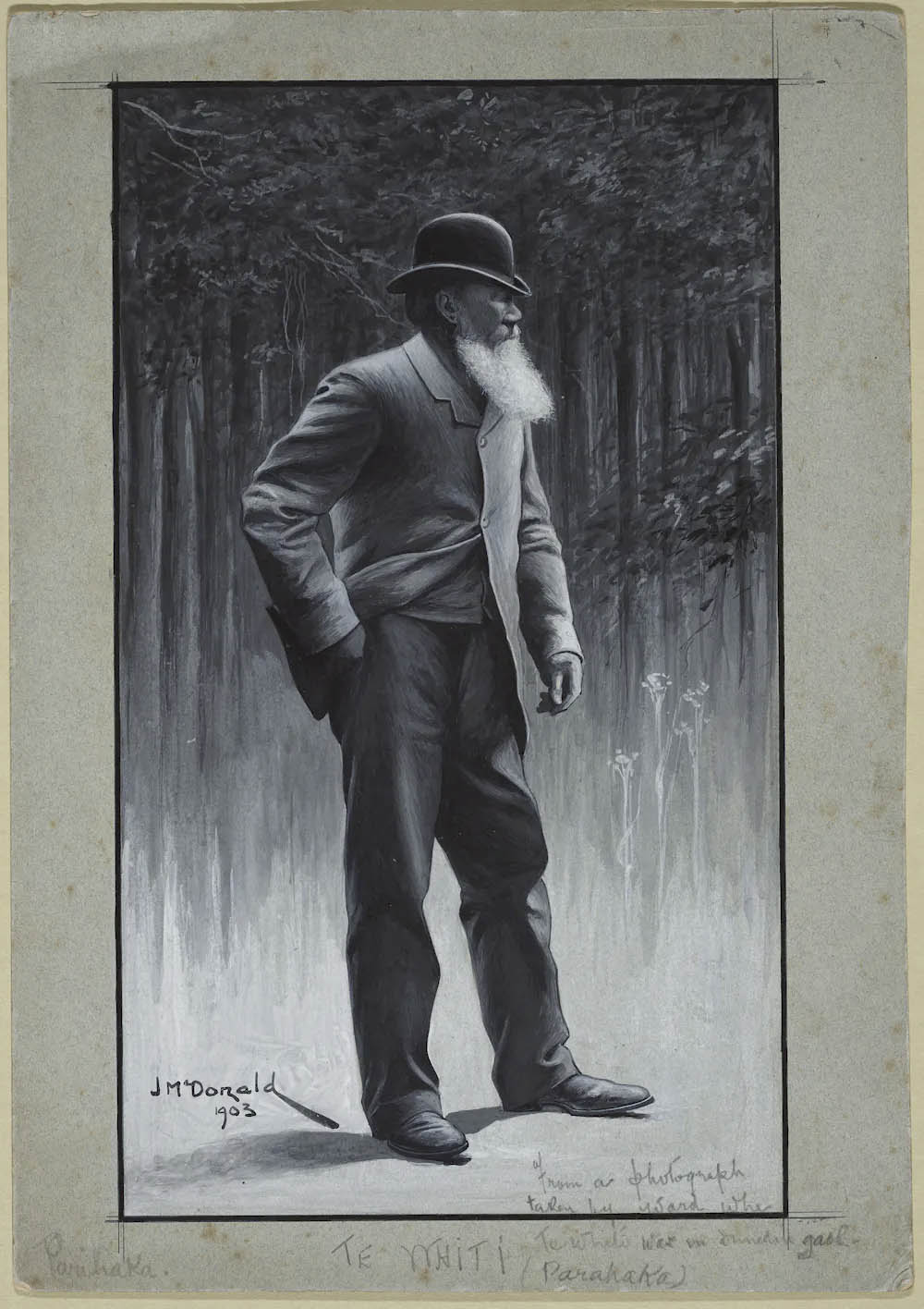

James Ingram McDonald (New Zealand 1865-1935)

Te Whiti

c. 1903

Alexander Turnbull Library

James Ingram McDonald (11 June 1865 – 13 April 1935) was a New Zealand painter, photographer, film-maker, museum director, cultural ambassador film censor, and promoter of Maori arts and crafts.

James McDonald was born in Tokomairiro, South Otago, New Zealand on 11 June 1865. He began painting early in his life and took art lessons as a young man in Dunedin with James Nairn, Nugent Welch and Girolamo Nerli. He continued his art studies in Melbourne, Australia, but returned to New Zealand in 1901, where he worked as a photographer. From 1905 he was a museum assistant and draughtsman in the Colonial Museum, later to become the Dominion Museum and even later the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa). He began making films about various scenic sights. At the museum he was responsible for the maintenance of the photographic collection and the production of paintings, drawings and photographs for the Dominion Museum bulletins.

He began to gather information about Māori tribal traditions. His films show poi dances and whai string games. He was probably the earliest known ethnographic filmmaker in New Zealand. In 1920 he filmed the gathering of the Māori tribes in Rotorua, when they welcomed the Prince of Wales, and other aspects of the royal journey. He filmed traditional skills and activities, including the make of fishing nets and traps, weaving, digging kumara camps and cooking food in a hangi. Most of his often unedited and fragmentary negatives became only known in 1986 after restoration by the New Zealand film archive. …

He died in Tokaanu on 13 April 1935 and was buried at Taupo cemetery. The School of Applied Arts, which he had founded, doesn’t exist anymore, but many examples of McDonald’s work have been preserved. Many hundreds of his photographic negatives are kept by the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. There are prints of his works in the collections of the Alexander Turnbull Library and the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Hawaii. The four ethnographic films he has made are preserved in the collection of the New Zealand Film Archive Nga Kaitiaki or Nga Taonga Whitiahua.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Te Whiti o Rongomai III (c. 1830 – 18 November 1907) was a Māori spiritual leader and founder of the village of Parihaka, in New Zealand’s Taranaki region.

Te Whiti established Parihaka community as a place of sanctuary and peace for Māori many of whom seeking refuge as their land was confiscated in the early 1860s. Parihaka became a place of peaceful resistance to the encroaching confiscations. On 5 November 1881, the village was invaded by 1500 Armed Constabulary with its leaders arrested and put on trial. Te Whiti was sent to Christchurch at the Crown’s insistence after it was clear the crown was losing its case in New Plymouth. The trial, however, was never reconvened and Te Whiti, along with Tohu were held for two years. Te Whiti and Tohu returned to Parihaka in 1883, seeking to rebuild Parihaka as a place of learning and cultural development though land protests continued. Te Whiti was imprisoned on two further occasions after 1885 before his death in 1907.

Text from the Wikipedia website

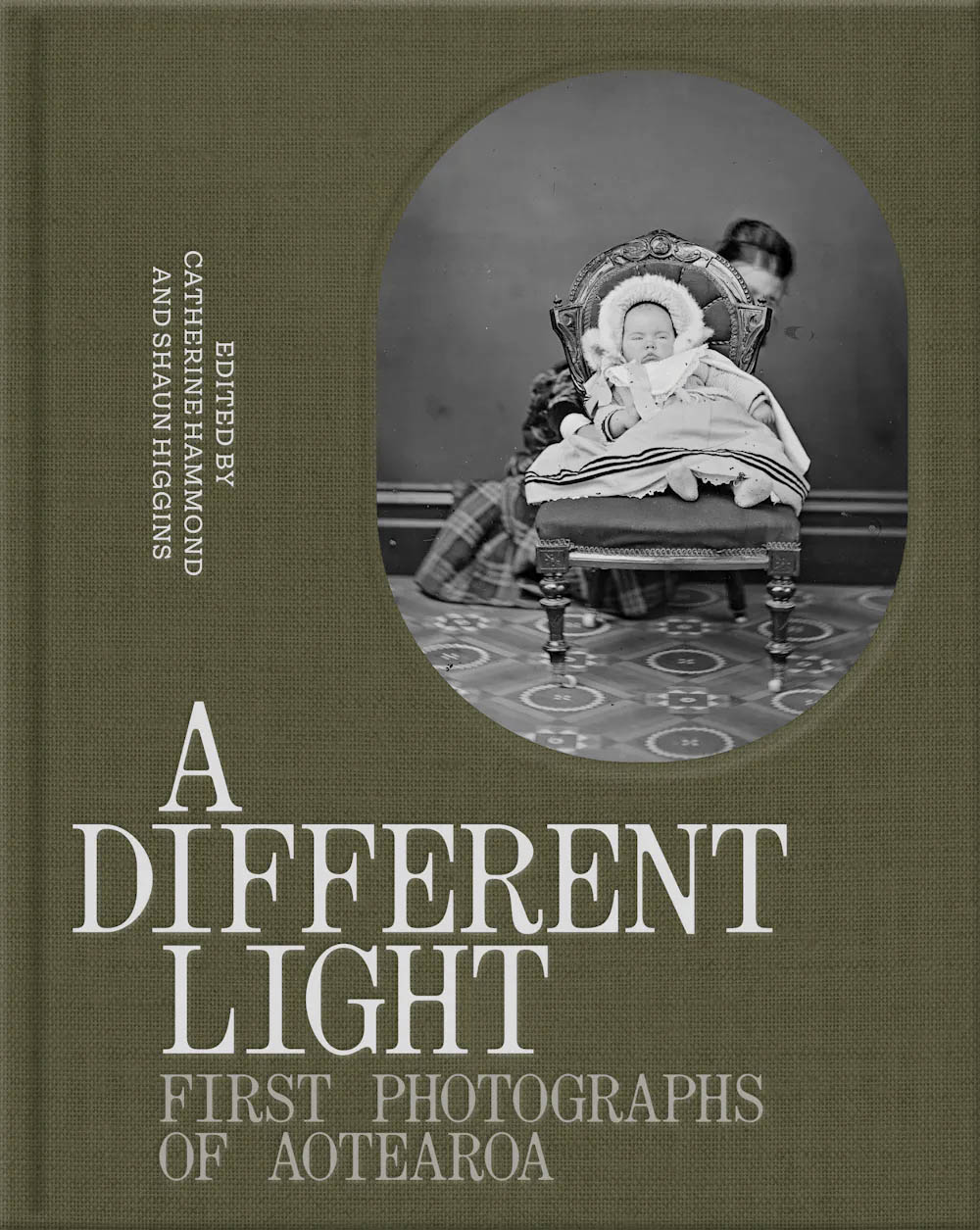

A Different Light – First Photographs of Aotearoa book cover

The mīhini mīharo reveals nineteenth-century Aotearoa as never before.

In 1848, two decades after a French inventor mixed daylight with a cocktail of chemicals to fix the view outside his window onto a metal plate, photography arrived in Aotearoa. How did these ‘portraits in a machine’ reveal Māori and Pākehā to themselves and to each other? Were the first photographs ‘a good likeness’ or were they tricksters? What stories do they capture of the changing landscape of Aotearoa?

From horses laden with mammoth photographic plates in the 1870s to the arrival of the Kodak in the late 1880s, New Zealand’s first photographs reveal Kīngi and governors, geysers and slums, battles and parties. They freeze faces in formal studio portraits and stumble into the intimacy of backyards, gardens and homes.

A Different Light brings together the extraordinary and extensive photographic collections of three major research libraries – Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum, Alexander Turnbull Library and Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena – to coincide with a touring exhibition of some of the earliest known photographs of Aotearoa.

Editors

Catherine Hammond is the director of collections and research at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum. She was formerly Hocken Librarian at the University of Otago Te Whare Wānanga o Ōtākou, and before that head of documentary heritage at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum and research library manager at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki.

Shaun Higgins is curator pictorial at Tāmaki Paenga Hira Auckland War Memorial Museum. He has worked on exhibitions for two decades, most recently Robin Morrison: Road Trip (2023). He has an MA, BA and PGDip from the University of Auckland in anthropology, art history and museum studies, and further qualifications in photography and care and identification of photographs.

Alongside the editors, A Different Light includes essays by Angela Wanhalla (Kāi Tahu), professor of History at the University of Otago; Paul Diamond (Ngāti Hauā, Te Rarawa, Ngāpuhi), curator, Māori at the Alexander Turnbull Library; Anna Petersen, curator, Photographs at Hocken Collections Uare Taoka o Hākena; and Natalie Marshall, formerly curator, Photographs at Alexander Turnbull Library.

Text from the Auckland University Press website

A Different Light – First Photographs of Aotearoa Introduction to book

A Different Light – First Photographs of Aotearoa book pages

Auckland War Memorial Museum

The Auckland Domain Parnell,

Auckland New Zealand

+6493090443

Opening hours:

Open weekdays from 10am – 5pm.

Open Saturdays, Sundays, and public holidays from 9am – 5pm.

Open late every Tuesday evening until 8.30pm

![James Coutts Crawford (New Zealand born Scotland, 1817-1889) 'Nurse Edgar [left] and Jessie Crawford' c. 1860 James Coutts Crawford (New Zealand born Scotland, 1817-1889) 'Nurse Edgar [left] and Jessie Crawford' c. 1860](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/crawford-nurse-edgar.jpg)

![Henry Wright (New Zealand, 1844-1936) 'Rahui Te Kiri Tenetahi [right] and her daughter Ngāpeka Te Roa of Ngāti Manuhiri' 1893 Henry Wright (New Zealand, 1844-1936) 'Rahui Te Kiri Tenetahi [right] and her daughter Ngāpeka Te Roa of Ngāti Manuhiri' 1893](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/henry-wright-rahui-te-kiri-tenetahi-and-her-daughter.jpg)

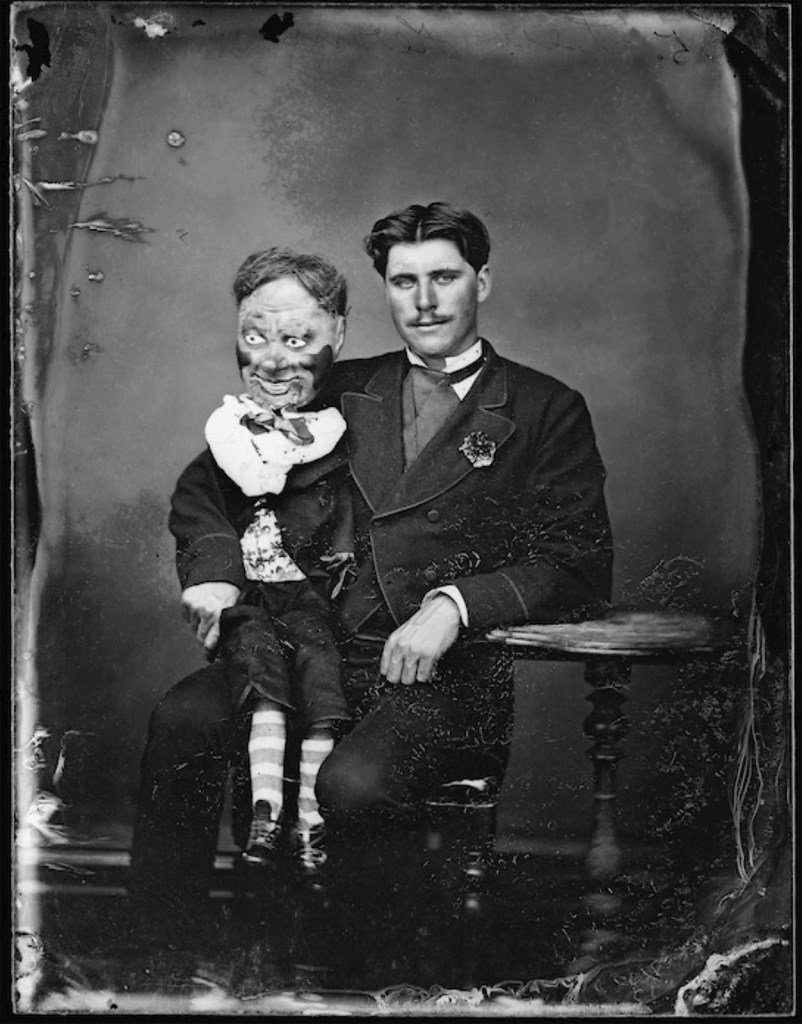

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Between skin & shirt: The photographic portraits of William Harding' at the National Library of New Zealand Gallery, Wellington showing at left, '[Miss] Scott' (between 1870-1889); at second left, 'Woman on left wearing large crinoline dress with black jacket with tassels and belt above the waist, woman on the right wearing crinoline dress with tassels on top part of dress' (between 1870-1880); at centre, 'Lieutenant Herman with his ventriloquist dummy' (c. 1877); and at second right, 'Members of the Burne family' (between 1856-1889) Installation view of the exhibition 'Between skin & shirt: The photographic portraits of William Harding' at the National Library of New Zealand Gallery, Wellington showing at left, '[Miss] Scott' (between 1870-1889); at second left, 'Woman on left wearing large crinoline dress with black jacket with tassels and belt above the waist, woman on the right wearing crinoline dress with tassels on top part of dress' (between 1870-1880); at centre, 'Lieutenant Herman with his ventriloquist dummy' (c. 1877); and at second right, 'Members of the Burne family' (between 1856-1889)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/20220525_nl_pe_ge_between_skinshirt_opening_003.jpg)

![William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) 'Fraser' [Consump?] Between 1856-1899 William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) 'Fraser' [Consump?] Between 1856-1899](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/harding-fraser-consump.jpg?w=790)

![William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) '[Mrs?] Keen' Between 1870-1889 William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) '[Mrs?] Keen' Between 1870-1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/harding-mrs-keen.jpg?w=782)

![William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) '[Miss] Scott' Between 1870-1889 William James Harding (New Zealand, 1826-1899) '[Miss] Scott' Between 1870-1889](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/harding-miss-scott.jpg?w=783)

You must be logged in to post a comment.