Exhibition dates: 24th October 2015 – 14th February 2016

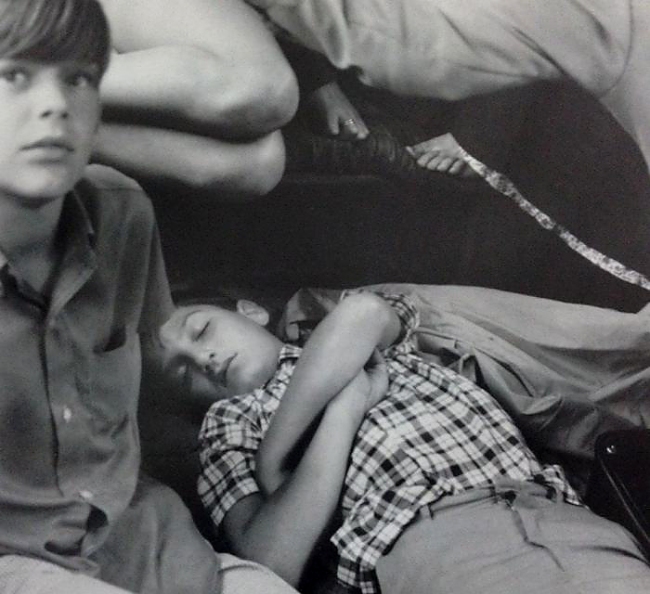

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1930

Silver gelatin print

13 x 18cm

© Private collection

The multiple singularities of photography

Photograph, photographer, negative, print

I have never thought of photography as a “singularity” – the singularity of photography. For me, photography has always been about possibilities, multiplicities rather than singularities.

In Kathrin Yacavone’s text below, the “singularity of photography” is defined as the relationship – the hierarchy – among valuable, perceptual and imaginative relations between the beholder and the image. It is the singularity of the individual and their response at any time to a photograph, but these responses cannot be systematically codified, in the sense that no response can ever be relied upon… certainly, no response to a photograph of a mother could be more singular than the response of a son (as claimed by Barthes Camera Lucida).

In other words, the singularity of photography is how the viewer engages and reads a photograph in a singular way at one point in time, from one “point of view.”

While this point of view is singular, it changes from moment to moment, from context to context, from different points of view. Hence, we have a multiplicity of singularities or, if you like, a multiple singularity of photography. Hasn’t it always seemed false to you in Camera Lucida where Barthes talks about his response to an image (for example, the supposed “lost” image of his mother*), he allows it to freeze in his text? Surely he would feel different later (another singularity). And yet the freezing is necessary for the arguments Barthes makes.

It continues to haunt me – much as photographs haunt our memory – why Barthes stuck with the singularity of a photograph, when at the same time he was pushing the multiplicity of readings in his other texts eg. S/Z (1970). Are we missing something really basic here? Why should a photograph be frozen and a text not?

In this exhibition, Michel Frizot defines a series of classifications (or themes, see below) that seek to organise the ambiguity and perplexity of vernacular and surprising photography. As Frizot himself puts it, “the photograph is not in its essence a transparency through which we gain access to a known reality but, on the contrary, a source of ambiguity and often, perplexity. The photographic image is a constellation of questions for the eye because it offers viewers forms and signs they have never perceived as such and which conflict with their natural vision”.

Frizot suggests questions for the eye offered through forms and signs that are in conflict with natural vision. Barthes pushes further, suggesting that it is not the forms and signs of the photograph that challenge natural vision, but a shift away from a semiology of photography to a phenomenology of photography. From guided message (forms/signs) to emotive response (imagination). Umberto Eco comments that, “Semiology shows us the universe of ideologies, arranged in codes and sub-codes, within the universe of signs, and these ideologies are reflected in our pre-constituted ways of using the language,”1 but Barthes, in works such as S/Z, stresses the multiplicity of a reading (its intertextuality). He contends that there can be no originating anchor of meaning in the possible intentions of the author, and that meaning must be actively created by the reader through a process of textual analysis.

An emotive response to a photograph is an “encounter with the represented other [is] a dialectical relationship between the specific and the general, between the personal and the universal, where the dialectic is seen in the psychologically unsettling potential of photographic images, the status of the photographic referent and the poignancy of the relation between time and image.” Thus the photograph can have a capacity for plurality of meaning which is not restrictive.

This response is based on an individuated, ‘feeling’ viewer whose encounter with the photograph is guided by desire and emotion, grounded in his or her unique experience and life history. It is to engage with the photograph in imaginative, affective, and emotional ways. Here, the codified reading is subsumed? by the emotive reading of an enlightened and fully “conscious” reader in the phenomenology of photography. Phenomenology is the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. The central structure of an experience is its intentionality, its being directed toward something, as it is an experience of or about some object – a photograph for example – by the imagination, by thought. Phenomenology requires a bit to grasp – to read a phenomenologial text like Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space as its author intended requires a cultivated mindset – but a prepared reader has many pleasures.

This is one possible response by the viewer to unsettling photographs. But what of the photographer?

Les Walking (my lecturer at RMIT University for many years), used to ask “what are you pointing your camera at?”… so this would permit an imaginative journey on his part as he imagined the subject matter, what he knew of the person, and all possibilities. Sometimes everything happens at once (in photography), and sometimes we recognise the richness of where we are in photography’s ability to generate many singularities within us at rapid fire.

As a photographer we go on an imaginative journey when we take a photograph – we previsualise, snap, extend the “point” of exposure (long time exposure), double expose or do away with the camera altogether. Taking a photograph is a multiplicity before the moment of the pushing of the shutter (decisions, angles, camera, film, light, place etc..), and a multiplicity afterwards… but for that split second it is a singularity, “an encounter with the represented other” as Walter Benjamin puts it… as though time, history and memory are all focused through the lens (of the camera, of the enlarger, of the scanner) at the object – like a funnel – which then expands afterwards. At the point of “exposure” there is only ever one singularity. Multiple contexts before and after, multiple phenomena if you like, but only one outcome when the negative is exposed. Being aware of all that happens around us leads to that one singularity – the negative. That’s what photographers do, they focus that energy into a singularity.

But the resulting negative is NOT singular!

Of course, there are some things that are forever predetermined in the analogue negative, eg the depth of field, the focus, the grain. Even in the digital negative these determinations apply. But then you think, if I push this film or pull it back in development “other” things may appear. Probably the Leica manual is as good as any for what come after that – they say that when shooting a roll of film with a variety of tonal scales the exposure should be more than the meter indicated, and the development time less. In the Zone System this would be N-1. And a negative like this is what gives the greatest options with graded papers. Multiple options for printing, multiple options for interpreting a negative. I feel these multiple options have been more or less forgotten in the era of the digital print. What you see on the screen is what you aim to see in the print, which negates the multiplicity of the (digital) negative, often leading to bland and underwhelming digital prints. The pre-determination of the screen leads to an over-determination of the print.

While Minor White observed that there was a dragon in the negative that could be reached by careful printing, this locks you into looking for the “one road” in the negative. One person who didn’t was the English photographer Bill Brandt who printed first in a straight documentary style before “unlocking” the surrealist elements of his negs with very contrasty work. He was open to the multiple contexts of the point of exposure of the negative, and it is his later reprinting of his earlier work for which he has become famous.

While it comes down to only several elements when talking about the phenomena of the negative, it is our direct experience of it IN OUR IMAGINATION that, perhaps, gives the negative presence and transcendence. It is the direction of our thought towards the object of our being. And that is what makes us truly human.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

* Of course, the photograph of his mother did exist, it was just necessary for his argument that we never see it, and that he said that it did not exist.

Word count: 1,400.

1/ Eco, U. (1970). “Articulations of the Cinematic Code,” in Cinematics, 1(1), pp. 590-605

Many thankx to my mentor for his advice and thoughts on this text. Many thankx to the Fotomuseum Winterthur for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Anonymous (Press Photo)

Rock and Mud ‘Grand Finale’

California, c. 1930

Silver gelatin print

19.7 x 24.7cm

© Private collection

Photographs often seem familiar and understandable, a visual common sense intimately related to our daily lives. But they can also provoke a spark of amazement or generate a more sustained perplexity and inquiry. Curated by the renowned French photo historian, Michel Frizot, Every Photograph is an Enigma interrogates this paradox. Drawing exclusively from photographs in his private collection, many of them anonymous, he presents a selection of photographic moments at once ordinary and marvellous. Frizot develops a system of classification that explores the strangeness generated by the camera lens. Taken by family members, lovers, or unheralded professional and amateur photographers, the assembled images amount to nothing less than a phenomenology of photography.

The exhibition and book are divided into eleven themes, such as:

Ambiguous assemblages

The enigma of relationship

The enigma of context

The enigma of attentiveness

Challenging the figurative order

The aesthetic solution

Original configurations

The photographer’s options

The space of the gaze

The spirit of the place

Anonymous (Keystone)

Professor Piccard’s Balloon Destroyed by Flames

25th May 1937

Silver gelatin print

13.4 x 18.5cm

© Private collection

The stratosphere balloon of Professor Piccard catches fire in the moment of ascending over the area of Brussels, Belgium.

Auguste Antoine Piccard (28 January 1884 – 24 March 1962) was a Swiss physicist, inventor and explorer known for his record-breaking helium-filled balloon flights, with which he studied the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Piccard was also known for his invention of the first bathyscaphe, FNRS-2, with which he made a number of unmanned dives in 1948 to explore the ocean’s depths.

“Every photograph is an enigma for the gaze: for the enigma is part of the photographic act itself. It ensues from the distance between the natural vision and the camera’s photosensitive capture process. By widening this gap, the modes of capture, the photographer’s intentions, and the reactions and involvement of the “photographer” together create new forms and perceptual requirements specific to photography. It is a question, above all, of understanding how much photographs, by transcending our visual capacities and going beyond our intuitions, also give rise to empathy and the need to project personal concerns. The element of enigma in photography bears witness, in fact, to what it is to “be human”.”

“The answer to the Sphinx’s riddle, it should be remembered, is humankind. And looking at a photograph means discovering oneself and the human species. Through the disparity and the dissonance between what it shows and what we experience, photography testifies above all, and at every moment, to what “being human” means. And the riddle, the enigma inherent in looking at a photograph is that of our presence in the world.”

Michel Frizot

Kathrin Yacavone. Benjamin, Barthes and the Singularity of Photography. Bloomsbury Academic, 2012, pp. 123-124

Mr. Brodsky

Marchand ties, Paris

1935

Silver gelatin print

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1930

Silver gelatin print

5.9 x 8.1cm

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1950

Silver gelatin print

6.5 x 9cm

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer (Hollywood Press photo)

The Photographer set on by His “Victim”

1938

Silver gelatin photograph

16.9 x 22cm

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer (International News Photos)

Untitled

Nd

Silver gelatin print

16.5 x 21.5cm

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer (International News Photos)

Untitled (detail)

Nd

Silver gelatin print

16.5 x 21.5cm

© Private collection

France-Presse

C’est demain mardi-gras / Tomorrow is Shrove Tuesday

March 5, 1935

Silver gelatin photograph

© Private collection

Interpress

Avant l’ouverture du Salon des Surindépendants / Prior to the opening of Superintendent’s Fair

Paris, 1952

Silver gelatin photograph

© Private collection

Mondial Photo-Presse

Réunion de modélistes

c. 1930

Silver gelatin photograph

12.8 × 17.6cm

© Private collection

NYT Photo

Wind Tunnel in Chalais Meudon

1935

Silver gelatin print

18 x 24cm

© Private collection

Photographs often seem familiar and understandable, a visual common sense intimately related to our daily lives. But they can also provoke a spark of amazement or generate a more sustained perplexity and inquiry. Curated by the renowned French photo historian, Michel Frizot, Every Photograph is an Enigma interrogates this paradox. Drawing exclusively from photographs in his private collection, many of them anonymous, he presents a selection of photographic moments at once ordinary and marvellous. Frizot develops a system of classification that explores the strangeness generated by the camera lens. Taken by family members, lovers, or unheralded professional and amateur photographers, the assembled images amount to nothing less than a phenomenology of photography.

Immediately a photograph is taken it generates a distance between what the image reveals and what we have seen for ourselves only seconds before. This observation of disparity is central to the phenomenon of photography, creating a sense of indeterminacy that we might describe as the singularity of the photographic. As Frizot himself puts it, “the photograph is not in its essence a transparency through which we gain access to a known reality but, on the contrary, a source of ambiguity and often, perplexity. The photographic image is a constellation of questions for the eye because it offers viewers forms and signs they have never perceived as such and which conflict with their natural vision”. Every Photograph is an Enigma draws out the full implications of this disparity, everything which constitutes the singularity of the photographic process. This begins with the selection procedure itself: Frizot has collected the photographs over many years, with no predetermined objective, finding scraps and castoffs at flea markets and jumble sales. Abandoned photographs escape traditional standards of classification and judgement and are often the work of anonymous photographers. For Frizot, this artlessness offers ‘an extra touch of photographic naturalness which is not shrouded in conventions’. It is the work of the exhibition to reveal, and the role of the visitor to discover, this photographic supplement.

The exhibition explores the modalities of photographic capture and the out-distancing of the senses that results, above all in the relationship between photographer, subject photographed and the operations of the camera, a technical device. Recording different intensities of light on a photosensitive surface, photography is an index of states of light rather than the reality perceived by the eye. The formal consequences of photographic technique are considerable, whether determined by exposure time, framing, exhaustive detail, or the projection of three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional surface. At the same time, what are fundamentally physical processes are also determined by the split-second decisions taken by the camera operator. It is precisely this that gives rise to the puzzle of photography: the contradictions between the precision of a physical world and the decision-making of the photographer.

Every Photograph is an Enigma explores other aspects of the riddle of photography, including the complexity of the exchange with the subject of the photograph, embodied by a reciprocal glance. The ability of the camera to record human form and gesture is what lends it its quasi-magical vocation. However, that act of recording is dependent on a vast array of potentialities and constraints, including perhaps the demeanour of the participants. The photographic act transforms emotionally-charged, interpersonal experience into uncertain, interpretable signs, a distillation of affect. At the same time, those signs are also dependent on the astuteness of the eyes that scrutinise the photograph, igniting, perhaps, an empathy with others. A photograph is a fragmentary capture and the gaze of the viewer operates in similarly fragmentary bursts. A viewer’s optical capacities are decisive, interpreting, for example, the photograph’s excess of data. The enigma of photography also emerges from the inadequacies and impasses of the energetic viewer’s scrutiny. These, and many other riddles, are explored across eleven separate chapters in the exhibition, which together provide a method for specifically photographic viewing. They probe the way the photographic device is used to celebrate the subject, or the way that processes unique to photography and the photographer’s command of his or her equipment help determine the final image. A further theme investigates the way that viewers are involved in a perceptual relationship which ordinary vision has not accustomed them to, including a display of stereo images. We encounter the myriad ways that photography overwhelms our senses and the many puzzles it presents.

Every Photograph is an Enigma brings together a remarkable selection of everyday photographs, selected over many years by one of the sharpest eyes in the history photography. It offers us the opportunity of a liberated escape into a ‘pure’ photographic act stripped of artistic pretension or historical portent. As Frizot proposes, there are no hierarchies in photography – it is the activity of the gaze that reveals the richness of the image. For the eye, every photograph is an enigma.

Catalogue

The exhibition is accompanied by the fully-illustrated catalogue Toute photographie fait énigme/Every photography is an enigma, by Michel Frizot, in collaboration with Cédric de Veigy. Published by Éditions Hazan. English/French with a German translation of the main texts. Price 45 CHF.

Credits

The exhibition is curated by Michel Frizot and organised by the Maison Européenne de la Photographie, Paris and the Musée Nicéphore Niépce, Chalon-sur-Saône in collaboration with Fotomuseum Winterthur.”

Text from the Fotomuseum Winterthur website

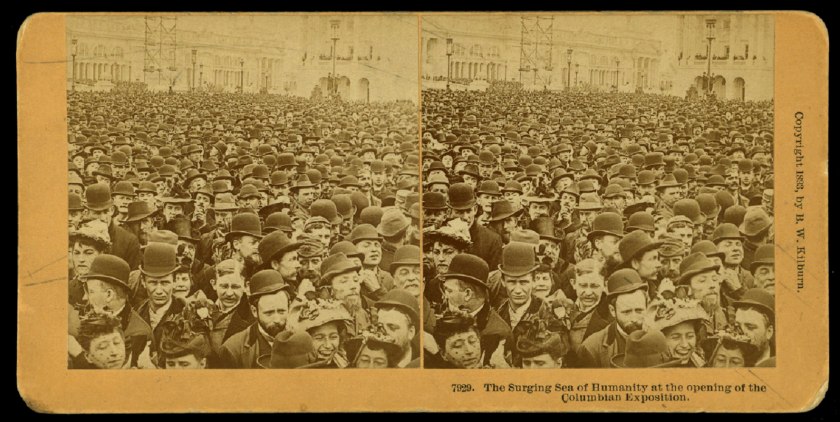

B.W. Kilburn (American, 1827-1909)

The Surging Sea of Humanity at the Opening of the Columbian Exposition, Chicago

1893

Stereocard

Albumen photographs

© Private collection

B.W. Kilburn (American, 1827-1909)

The Surging Sea of Humanity at the Opening of the Columbian Exposition, Chicago (detail)

1893

Stereocard

Albumen photograph

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1900

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Untitled (Flagrants délits / Egregious crimes)

c. 1955

Silver gelatin print

5.5 x 5.5cm

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

Instamatic Kodak

c. 1970

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Children Watching the Apollo 12 Flight on Television

1969

Silver gelatin photograph

© Private collection

For many years, Michel Frizot the historian and theorist has been collecting neglected photographs which have been overlooked because they were taken by anonymous, unknown photographers, unheard-of or non-celebrated artists, throughout the entire history of photography. Avoiding “museumification” and classification, selected first of all for their capacity for surprise, these photographs are no less generous, moving and perhaps “photographic” than others. This exhibition reflects on the element of mystery in all photography.

“Because they are so familiar to us, because they are part of our visual space, photographic images seem to be immediately accessible and understandable. But everyone has experienced that sudden burst of amazement they can set off through suspended movements, the rendering of colours, unexpected coincidences or abruptly frozen expressions. If we pay attention to such features, they provoke the feeling that we are faced at once with something obvious and with a question. When we can look at a photograph as soon as we have “taken” it, we immediately, moreover, sense the distance between what the image tells us and what we have been able to see for ourselves only seconds before. The observation of this disparity, recognisable at every moment, is proper to the photographic phenomenon. We grant each photograph an element of truth but suspect its indeterminacy and sense its contradictions.

The photographic image is a constellation of questions for the eye because it offers viewers forms and signs they have never perceived as such and which conflict with their natural vision.

The enigma, the riddle, the puzzle would thus be fundamental to the photographic act itself.

Inherent in the photographic process, it results from the irreducible distance between the human senses and the camera’s light-sensitive capture: it arises from the split between visual perception and the photographic process.

For the eye, every photograph is an enigma.

Whether they are kept in archives, family albums or agencies, or dumped in the street, photographs are virtual objects which only begin to exist when they find a viewer. The selective collecting process is thus carried out “by eye” and not the eye of the connoisseur or the historian, but the paradoxical eye which goes against the tide of the canonically “good” photograph, it is a slow eye which opens itself to the pleasure of choice. The pursuit of irreplaceable strangeness. A determined eye, in search of what it does not yet know and yet perceives as the baring of the “photographic”, the liberated escape into a “pure” photographic act stripped of its eloquence. By repeating the selections, the eye discovers the unknown properties of the photographic image: it spots the elements of a puzzle to be savoured without anticipation of any solution. As a kind of practical application, when we look closely, these photographs seem more “photographic” than so many other images with more conventional features that quickly lose their interest. They reveal what escapes us in the recognition of the world, what lies beyond its photographic figures repeated over and over again.

The answer to the Sphinx’s riddle, it should be remembered, is humankind. And looking at a photograph means discovering oneself and the human species. Through the disparity and the dissonance between what it shows and what we experience, photography testifies above all, and at every moment, to what “being human” means. And the riddle, the enigma inherent in looking at a photograph is that of our presence in the world.”

Michel Frizot

Extract from the book Toute photographie fait énigme / Every photograph is an enigma, Hazan, 2014

Michel Frizot quoted in “Every Photograph is an enigma,” on the Musée Nicéphore Niépce website [Online] Cited 07/20/2021

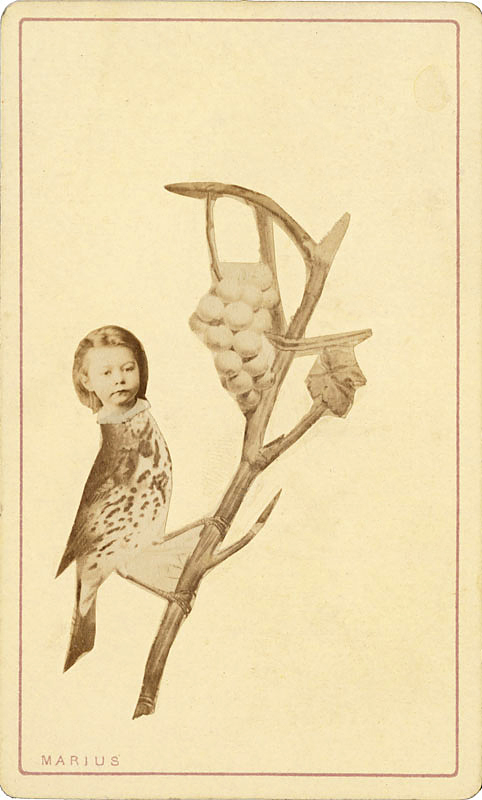

Marius, Paris

Photomontage

c. 1865

Albumen print

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1910

© Private collection

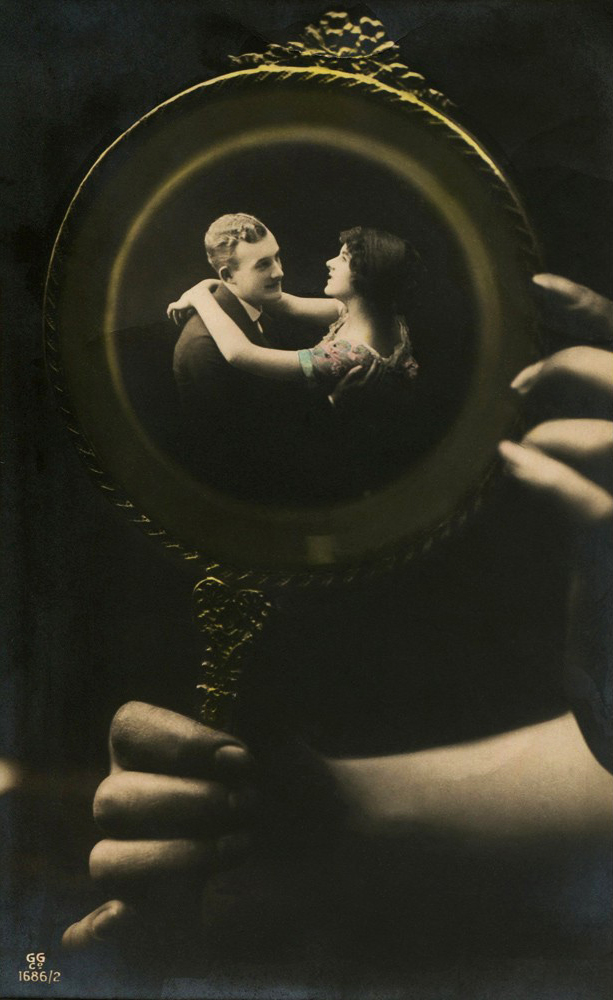

Anonymous photographer

Photomontage (photographic postcard)

c. 1920

Silver gelatin print

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Studio Portrait (Photographic postcard)

c. 1910

Silver gelatin print

9 x 14cm

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1930

Silver gelatin print

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Photographie transcendetale avec visages d’ectoplasms / Transcendental photography with faces of ectoplasm

1939

Silver gelatin print

© Private collection

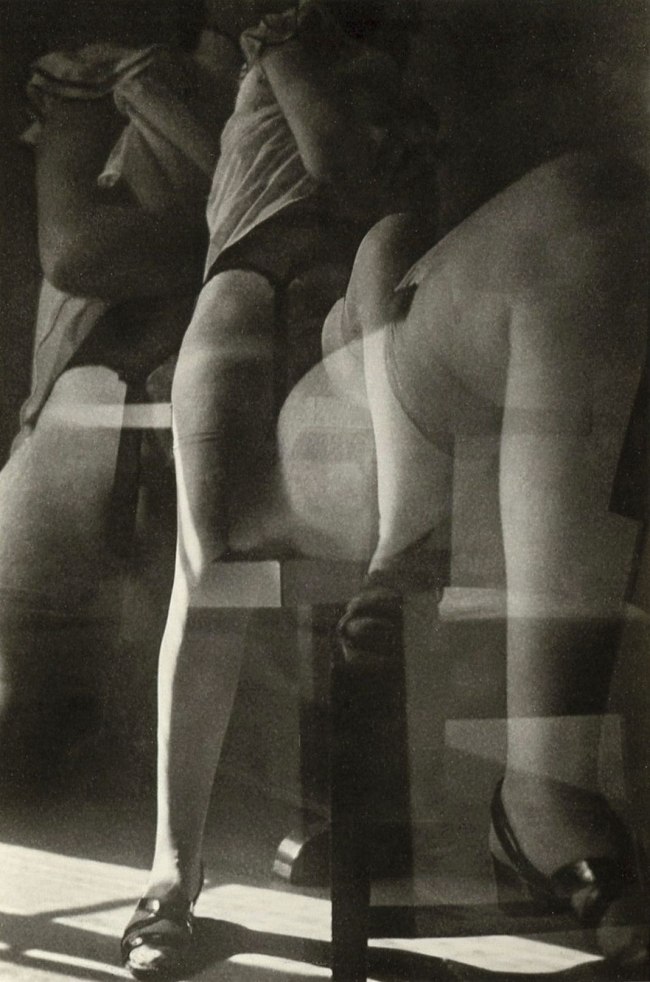

Anonymous photographer

Untitled (Surimpression)

c. 1935

Silver gelatin photograph

8.2 × 5.4cm

© Private collection

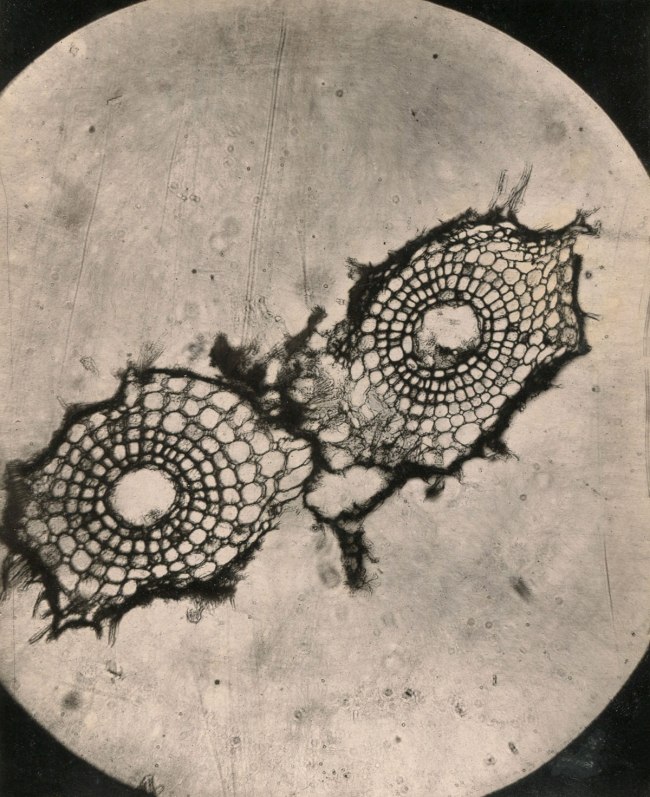

L. Olivier

Recherches sur l’appareil tégumentaire des racines Marsilea Quadrifolia

(Photomicrographic plate)

1881

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer (Press photo)

Patriot Missile Warheads Promoters

1991

Gelatin silver print

25.3 x 20.2cm

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Dans un local désaffecté de Budapest, les corps de patriotes hongrois voisinent avec une statue déboulonnée à la gloire du sport soviétiqueMembers of the State Protection Authority, ÁVH

In some abandoned premises in Budapest, the bodies of Hungarian patriots lie beside a statue removed from its base [dedicated] to the glory of Soviet sports

Budapest, 1956

Gelatin silver print

29.8 × 22.6cm

© Private collection

Victims of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 brutally put down by the Russians.

Addendum

According to the experts at Fortepan, an open access public resource of the Hungarian audio-visual culture, the dead men in the photograph above are very likely (~99%) not patriots, but members of the State Protection Authority, ÁVH- Államvédelmi Hatóság. The State Protection Authority was the secret police of the People’s Republic of Hungary from 1945 until 1956.

The photograph below recently found on the Fortepan website showing the above sculpture at second back left of the image.

Ismeretlen fotós. 1956. MagyarországBudapest XIII. Jász utca 74., a Képzőművészeti Kivitelező és Iparvállalat szoboröntödéjének udvara. Sóváry János Táncoló gyerekek alkotása és a mögötte lévő Pátzay Pál Integető című alkotása Budapesten, Antal Károly Birkózók és Mikus Sándor Labdarúgók szobra a Népstadion szoborkertjében, Szomor László Kígyóölő szobra Szolnokon a vérellátónál, Kisfaludi Strobl Zsigmond Kossuth Lajost ábrázoló szobra a Hősök terén került később felállításra.

Unknown photographer. 1956 Hungary, Budapest XIII. Jász utca 74, the yard of the sculptural foundry of the Fine Art Designer and Industrial Company. János Sóváry Creation of Dancing Children and the Pátzay Pál Integető, behind the Antal Károly Birkozók and Mikus Sándor Football Sculpture in the Népstadion Sculpture Garden, The Statue of László Szomor, The Snake Statue in Szolnok, The statue of Kisfaludi Strobl Zsigmond Kossuth Lajost was later erected in the Heroes’ Square.

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 or the Hungarian Uprising of 1956 (Hungarian: 1956-os forradalom or felkelés) was a nationwide revolt against the government of the Hungarian People’s Republic and its Soviet-imposed policies, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956. Though leaderless when it first began, it was the first major threat to Soviet control since the USSR’s forces drove out Nazi Germany from its territory at the end of World War II and broke into Central and Eastern Europe.

The revolt began as a student demonstration, which attracted thousands as they marched through central Budapest to the Parliament building, calling out on the streets using a van with loudspeakers via Radio Free Europe. A student delegation, entering the radio building to try to broadcast the students’ demands, was detained. When the delegation’s release was demanded by the demonstrators outside, they were fired upon by the State Security Police (ÁVH) from within the building. One student died and was wrapped in a flag and held above the crowd. This was the start of the revolution. As the news spread, disorder and violence erupted throughout the capital.

The revolt spread quickly across Hungary and the government collapsed. Thousands organised into militias, battling the ÁVH and Soviet troops. Pro-Soviet communists and ÁVH members were often executed or imprisoned and former political prisoners were released and armed. Radical impromptu workers’ councils wrested municipal control from the ruling Hungarian Working People’s Party and demanded political changes. A new government formally disbanded the ÁVH, declared its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact, and pledged to re-establish free elections. By the end of October, fighting had almost stopped and a sense of normality began to return.

After announcing a willingness to negotiate a withdrawal of Soviet forces, the Politburo changed its mind and moved to crush the revolution. On 4 November, a large Soviet force invaded Budapest and other regions of the country. The Hungarian resistance continued until 10 November. Over 2,500 Hungarians and 700 Soviet troops were killed in the conflict, and 200,000 Hungarians fled as refugees. Mass arrests and denunciations continued for months thereafter. By January 1957, the new Soviet-installed government had suppressed all public opposition. These Soviet actions, while strengthening control over the Eastern Bloc, alienated many Western Marxists, leading to splits and/or considerable losses of membership for Communist Parties in the West.

Text from the Wikipedia website

International Newsreel Photo

Governor of Alabama Arrested for Breaking Prohibition Laws

24th November 1926

Gelatin silver print

20 x 15cm

© Private collection

Anonymous photographer

Untitled

c. 1950

Gelatin silver print

7 x 4.5cm

© Private collection

Fotomuseum Winterthur

Grüzenstrasse 44 + 45

CH-8400

Winterthur (Zürich)

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Sunday 11am – 6pm

Wednesday 11am – 8pm

Closed on Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.