March 2014

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Aksai

1875

2 November 1875 – steamer Aksai (Russia) sailed into White Island, St Martin’s in thick fog while bound for Odessa from Cardiff with coal. The captain and crew of thirty-nine were saved by the Lady of the Isles. Citation: Larn, Richard (1992). Shipwrecks of the Isles of Scilly. Nairn: Thomas & Lochar.

“Other men have taken fine shipwreck photographs, but nowhere else in the world can one family have produced such a consistently high and poetic standard of work.”

.

John Fowles

“This is the greatest archive of the drama and mechanics of shipwreck we will ever see – a thousand images stretching over 130 years, of such power, insight and nostalgia that even the most passive observer cannot fail to feel the excitement or pathos of the events they depict.”

.

Rex Cowan

Dear readers, this gem of a posting will have to last you all of this week as it took such a long time to research, clean the images and assemble the post. I hope you enjoy the fruits of my labour.

These are superb photographs obtained in the most trying of conditions, forming an artistic practice that spans generations and epochs.

As the text below notes, “At the very forefront of early photojournalism, John Gibson and his descendants were determined to be first on the scene when these shipwrecks struck. Each and every wreck had its own story to tell with unfolding drama, heroics, tragedies and triumphs to be photographed and recorded – the news of which the Gibsons would disseminate to the British mainland and beyond.”

This is the most glorious archive of shipwreck photographs that the world has even known and this posting brings together the largest selection of these photographs available on the Internet at the moment, in one place. I have to send a big thank you to the Press Office of the Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) for sending me all these photographs and allowing me to post them on Art Blart. Unfortunately, because they had just been purchased from the auction house Sotheby’s, there was no information about each image, just the title of the ship. So I have spent hours researching the ships in this posting and cleaning up the scans that were sent to me, some of which were in a poor state. All the text comes from the Internet and if I have forgotten to credit someone I apologise in advance. I have included detailed close-ups of certain images to emphasise the drama, the calamity and the presence and inherent curiosity of onlookers.

The hours spent researching has all be worthwhile because the photographs are magnificent. Atmospheric, ghostly, tinged with loss, tragedy, heroism and the “presence” of these (mostly) sailing ships, these photographs are both memorials and romantic photographic ruins to the age of steam and sail. My favourite has to be the ghostly Flying Dutchman-esque The Glenbervie (1902, below), but for tragedy and poignancy you can’t go past the recumbent body of The Jeanne Gougy (1962, below), framed so beautifully by the artist in the horizontal, by just seen rocks.

But how can you pick just one or two? Each photograph has its own mystery, its own fiction, for as Susan Sontag observes, “Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation and fantasy.” In the case of these photographs we can only speculate as to the specific circumstances that led to the occurrence of each wreck (decisions made, or not), the set of circumstances and actions which are evidenced by the time freeze of these photographs, one end product of the performative act. Although they deny interconnectedness and continuity in the actual (conferring on each moment the character of a mystery), they enable interconnectedness and continuity in the imagination of the viewer for we can vividly imagine being on these ships as they are wrecked at sea.

What was interesting with this posting is that the images did not come with captions, just the name of the ship. My imagination was left free to roam, to scour the image for clues, to make up stories about what had happened until I did the research and the text based, “real” story emerged – the words becoming a means by which the viewer can decode the photographic evidence before them. Even though they were rushed to newspapers and magazines to impart news of the accident, I still prefer the fantasy of the image over the informational addendum, for this is what gives these images their power. Here, technology and the mistakes of man yield to the power of nature and you can only imagine how it would have been.

While the back story may add context of time, place, loss and heroism it is the beautiful isolation of these wrecked ships of the sea and their paradoxical nestling close in to the bosom of the earth, holding them fast, that will forever provide intimate fascination.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

.

Many thankx to the Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Bay of Panama

1891

SV Bay of Panama (British): The sailing ship was wrecked under Nare Head, near St Keverne, Cornwall, United Kingdom, during a great blizzard. The ship carried jute from Calcutta; 18 of those on board died but 19 were saved. Noall, C. (1969?) Cornish Shipwrecks Illustrated. Truro: Tor Mark Press; p. 15

Barque, built in 1883, 4 masts (equipped with floors and lower deck beams of iron. The forecastle was 37 ft long and the poop 54 ft. Rigged with double top- and top gallant sails and royal sails)

Built by the Belfast shipping firm of Hartland and Wolff in 1883, the Bay of Panama was described by everyone who saw her as probably the finest sailing ship afloat. With her steel hull, and four square-rigged masts, she was a very fast and beautiful ship of 2282 tons. But strength and good looks are no guarantee, and during March 1891 the Bay of Panama met up with the worst blizzard Cornwall had suffered for over two hundred years. It was to prove no contest. Because of her speed, the Bay of Panama was used on the Calcutta run, and on November 18th 1890 she left that port bound for Dundee loaded with a cargo of 13000 bales of jute.

For four months she sailed swiftly towards England until one morning during the early part of March 1891, she approached the Cornish coast in rapidly deteriorating weather. The Captain knew all about the dangers of a lee shore, but because of the bad visibility he was uncertain as to his exact position. He could see that the weather was unlikely to get any better, and he even thought that there might be some snow. After weighing up all the risks he decided to heave to, take some depth soundings, and generally take stock of his position. It was a decision that was to cost him his ship, and his life. Only a few hours later, in the early afternoon, a blizzard, the worst for over two centuries, swept into the West Country and engulfed the Bay of Panama.

Bay of Panama

Posted on July 4, 2007 Peter Mitchell

The Gibsons of Scilly

SS Blue Jacket

1898

SS Blue Jacket (United Kingdom) November 1898: She was unaccountably wrecked on a clear night a few yards from the Longships lighthouse, Lands End, Cornwall. The crew were saved by the Sennen lifeboat. Noall, C. (1969?) Cornish Shipwrecks Illustrated. Truro: Tor Mark Press; p. 21.

Stuck fast – and surely a classic example of the expression – on the Longships lighthouse rocks off Land’s End, December 9th, 1898. This tramp was in ballast from Plymouth to Cardiff. The captain went below to his cabin – and his wife – at 9.30 p.m., leaving the mate on watch. He was woken near midnight by a tremendous crash, and came on deck to find his listing ship brilliantly illuminated by the lighthouse only a few yards away. Captain, wife and crew took to their boats and were picked up by the Sennen lifeboat. How the mate managed to play moth to this gigantic candle – the weather was poor, but provided at least two miles’ visibility – has remained a mystery. The Blue Jacket sat perched in this ludicrous position for over a year.

John Fowles. Shipwreck. 1975

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Minnehaha

1874

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Minnehaha

1874

The Minnehaha was shipwrecked in 1874 as it travelled from Peru to Dublin. It was carrying guano to be used as fertiliser and struck Peninnis Head rocks when the captain lost his way. The ship sank so quickly that some men were drowned in their berths, ten died in total including the captain.

On 18 January 1874, while travelling from Callao, Peru to Dublin, the 845-ton four-masted barque Minnehaha carrying guano was wrecked off Peninnis Head, St Mary’s, Isles of Scilly. Her pilot mistook the St Agnes light for the Wolf Rock and thought they were passing between the Isles of Scilly and the Wolf. Shortly after she struck a rock off Peninnis Head and the vessel sunk at once with some of the crew being drowned in their berths. Those on deck climbed into the rigging, and as the tide rose the ship was driven closer to land, and some managed to climb onto the shore over the jib boom. The master, pilot and eight crew drowned.

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Mohegan

1898

The Mohegan struck the Manacles, October 14th, 1898. One of the most dreaded of all reefs, the Manacles (from the Cornish ‘maen eglos’, rocks of the church, a reference to the landmark of St Keverne’s tower) stand east of the Lizard promontory, in a perfect position to catch shipping on the way into Falmouth – and before Marconi ‘Falmouth for orders’ (as to final North European destination) was the commonest of all instructions to masters abroad. But the Mohegan was outward bound, and hers is one of the most mysterious of all Victorian sea-disasters. She was a luxury liner on only her second voyage, from Tilbury to New York. Somewhere off Plymouth a wrong course was given. A number of people on shore realised the ship was sailing full speed (13 knots) for catastrophe; a coastguard even fired a warning rocket, but it came too late. The great ship struck just as the passengers were sitting down to dinner. She sank in less than ten minutes, and 106 people were drowned, including the captain and every single deck officer, so we shall never know how the extraordinary mistake, in good visibility, was made. The captain’s body was washed up headless in Caernarvon Bay three months later. Most of the dead were buried in a mass grave at St. Keverne.

John Fowles. Shipwreck. 1975

The Gibsons of Scilly

MV Poleire

1970

The MV Poleire was a Cypriot motor vessel of some 2300 tons. In April 1970 she was on a voyage from Ireland to Gdynia in Poland carrying a cargo of zinc ore when she struck the Little Kettle Rock, which lies just north west of Tresco. There was a thick fog when she struck, and although less than a mile from the Round Island light house, her master failed to hear the fog signal. The sea was flat calm so all the crew managed to get off safely. Within a week the Poleire broke in two and sank.

MV Poleire

Posted on July 4, 2007 Peter Mitchell

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Jeanne Gougy

1962

The Jeanne Gougy, a French fishing trawler (built 1948) ran aground on the 3rd November 1962. Several crew were rescued by Sergeant Eric Smith from a Whirlwind Mk 10 helicopter when he was winched down to the wheelhouse despite it being submerged by breaking waves. He was awarded a George Medal for his rescues.

“The dramatic but tragic shipwreck in which eleven men died and the rescue of the rest of the crew of the Jean Gougy, occurred on November 3rd 1962. The French trawler out of Dieppe, was bound for the fishing grounds of the southern Irish coast when it went aground on the north side of Lands End. At 05.20h, the Sennen Coxswain was contacted by the coastguard who informed him of the trawler’s situation. The firing of the maroons at Sennen Cove awoke two young Royal Marines from their deep sleep, bivouacking as they were, on the flat concrete platform that then existed not far from the lifeboat station at Sennen Cove. The reserve lifeboat on temporary duty at the station was launched as the two marines slowly dozed off back to sleep.

The lifeboat took approximately one hour to reach the scene at Lands End. A parachute flare was fired and the trawler could be seen lying on her side on rocks at the foot of the cliff. A very heavy swell prevailed after the storm. It was impossible for the lifeboat to get any closer than a hundred yards. An L.S.A team at the top of the cliff had fired several lines over the trawler, but the crew could not secure them as the trawler was completely submerged by the heavy swell. Several men were washed out of the wheelhouse. At 8.15h a helicopter from Chivener arrived and, together with the lifeboat, carried out a search of the area. The lifeboat found two seamen and the helicopter one. They were all dead. At 9.00h the helicopter left for Penzance to land a body and to then refuel at Culdrose Naval Air Base near Helston.

“I had awoken with a start at the explosions around me, mistakenly in my stupor believing it was already bonfire night, which of course was two days away. I went back to sleep. Waking sometime later my climbing partner and I packed our equipment and proceeded to walk from Sennen Cove where we had been climbing the previous day, over to Lands End for another days climbing. As we approached Lands End, we noticed people standing on the northern headland. On arriving at approximately midday, we walked over to the zawn beneath us, into which a policeman was peering. There on it’s side was a trawler and looking up at us and waving were many trapped people in the wheelhouse.

Turning to the policeman I said “If my mate and I rope down this side of the zawn (there is a tidal platform, a ledge there), we can set up a belay station, throw our other rope in through the broken wheelhouse window and one by one pull those guys to the cliff below us” (the tide was going out). “Go away” was his curt reply. And so we walked away. In the next four hours, eight more fisherman lost their lives. The outcome could have been so very different.”

As there appeared to be no one left alive on the Jean Gougy the lifeboat had made for Newlyn to land two bodies, it being impossible to return to Sennen Cove due to the tide. At noon however a woman watching from the top of the cliff top saw a man’s hand waving inside the wheelhouse and heard him calling. The coastguards fired a line over the trawler and a man, clinging to the edge of the wheelhouse as the vessel was now completely on her side, struggled to grasp it. He was prevented by heavy waves. Eventually he secured the line and was hauled to safety in the breeches buoy. Three others being rescued afterwards by the same means. The helicopter, on being recalled, hovered over the ship and lowered a crewman who saved two more seamen. These six had survived by breathing trapped air in pockets at the wheelhouse and forecastle. On learning of these developments, the Penlee lifeboat Soloman Browne launched at 12.45h and arrived three-quarters of an hour later. The Sennen lifeboat also returned to the scene at 15.45h. With the helicopter they again searched the area but with no success. It was later learned that the trawler carried a crew of 18, 11 of whom lost their lives, including the skipper.

Sergeant E.C. Smith of the R.A.F who was lowered to the trawler to save the two injured men received the George Medal and also the Silver Medal of the Societe Nationale des Hospitaliers Sauveteurs Bretons. The stirring events connected with this shipwreck, which received extensive press and television coverage, provided an excellent illustration for the public of the manner of work the three principle sea rescue services provided in this country, and of the cooperation existing between them.”

Millenium Moments – The Jean Gougy – A personal recollection by Dennis Morrod on the guidinglight.org.uk website [Online] Cited 25/02/2014. No longer available online.

The Gibsons of Scilly

Jeune Hortense

1888

The French brigantine Jeune Hortense was swept on to the beach when she came into Mount’s Bay to land the body of a Fowey man who had died in France. The schooner wrecked at Long Rock, Cornwall. The Penzance lifeboat, having been brought by carriage to the beach near Marazion, rescued four crew.

Stranded near St Michael’s Mount, May lyth, 1888. The foreground carriage is for the Penzance lifeboat

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Mildred

1912

The Mildred was traveling from Newport to London when it got stuck in dense fog and hit rocks at Gurnards Head at midnight on the 6th April 1912. Captain Larcombe and his crew of two Irishmen, one Welshman and a Mexican rowed into St. Ives as their ship was destroyed by the waves.

“The British barquentine Mildred, Newport for London with basic slag, struck under Gurnards Head at midnight on the 6th April 1912, whilst in dense fog. She swung broadside and was pounding heavily when Captain Larcombe, the mate, two Irishmen, one Welshman and a Mexican from Vera Cruz rowed into St. Ives at 6am. They later returned in a pilot gig but the Mildred was already going to pieces. The Mildred, Cornish built and owned, was launched in 1889.”

The Gibsons of Scilly

SS Tripolitania

1912

SS Tripolitania Italian cargo ship (built 1897) ran aground on the 26th December 1912. Driven ashore in a Westerly gale, she beached and attempts were made to refloat her over the coming months on a spring tide. This was unsuccessful and she was eventually scrapped.

“Boxing Day 1912 was remembered by the advent of a south westerly gale, the full force of which was experienced at the Loe Bar, the stretch of shingle and sand separating the Loe Pool from the sea near Porthleven. This Italian Steamer Tripolitania was 2,297 tons. She became firmly embedded and despite strenuous efforts to release her from this perilous position, she was broken up and shipped as scrap from local Porthleven. It has been stated that about £8,000 had been expended on trying to save her. Many tons of sand and shingle were removed in an attempt to free the Tripolitania in the Loe Bar Sands and a great expense was incurred to try and salvage the ship. Tugs stood by for the attempt on the full tide on the morrow, but a storm arose during the night and embedded the vessel even firmer than before. After this incident hopes for refloating her were abandoned and she was broken up for scrap iron. One man was drowned and his body was never recovered.”

Anon. “Tripolitania,” on the Helston History website Nd

Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) today acquired a world renowned and nationally significant collection of photographic and archive material. The Gibson archive presents one of the most graphic and emotive depictions of shipwrecks, lifesaving and its aftermath produced in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The material was acquired at the Sotheby’s Travel, Atlases, Maps and Natural History Sale.

The archive of dramatic and often haunting images, assembled over 125 years (1872 to 1997) by four generations of the Gibson family, records over 200 wrecks – the ships, heroic rescues, survivors, burials and salvage scenes – off the treacherous coastline of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly. The acquisition of this collection comprising of over 1360 glass and film negatives, complements the Museum’s existing, extensive historic photography collection, and creates an unprecedented opportunity for the Museum to further examine and explore the story of life at sea and the dangers experienced by seafarers through research, education and display projects.

John Gibson (1827-1920) founded the family photographic business in the 1860s and took his first photograph of a wreck in 1869. He apprenticed his two sons Alexander (1857-1944) and Herbert (1861-1937), who perfected the art of photographing wrecks, creating perhaps some of the most remarkable and evocative images of misadventure at sea. Among the items included in the collection is the ledger the Gibson brothers kept when taking the photographs, which contains records of the telegraph messages sent from Scilly and is full of human stories of disaster, courage and survival. Having secured the archive RMG will initially conserve, research and digitize the collection, leading to a number of exhibitions to tour regional museums and galleries, especially those in the South West of England.

Lord Sterling of Plaistow, Chairman of the Royal Museums Greenwich, said: “The acquisition of this remarkable archive will enable us to create a series of exhibitions that will travel across the country, starting with the South West. I am very pleased that the National Maritime Museum has been able to secure this wonderful collection for the nation, and I know that the Gibson family are delighted that their family archive will remain and be displayed in this country.”

Items acquired today at auction:

- 585 Glass plate negatives (214: 12 x 10 in: 8 x 6 in) housed in 16 original wooden boxes and one cardboard box

- 407 Glass plate copy negatives (6½ x 4¾ in) in 4 cardboard boxes

- 179 Glass plate negatives (4¼ x 3¼ in)

- 198 film negatives (5 x 4 in) in three boxes

- 335 cut film negatives (various sizes) and 39 (35mm) film negatives

- 97 original photographs of shipwrecks (silver prints, 12 x 10 in)

- Manuscript ledger by Alexander and Herbert Gibson on the shipwrecks of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly

- A collection of books by John Fowles, John Arlott, John Le Carré, and Rex Cowan on the Gibsons of Scilly, together with newspaper and magazine articles

.

Text from the Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) website

Founder John Gibson bought his first camera 150 years ago

Alexander Gibson was invited by his father John into the business in 1865

Apprentice: Herbert Gibson was taken on by his father as an apprentice and went on to run the business

James Gibson took over the business after the death of his father Herbert

Frank Gibson spent time learning about new technology and techniques to help advance the family business

“The Gibson family originated from the Isle of Scilly and have 300 years of family history. John Gibson acquired his first camera whilst abroad around 150 years ago when photography was still mainly reserved for the wealthiest members of society. He had to go to sea from a young age to supplement the income from a small shop on St Mary’s run by his widowed mother. Making ends meet on St Mary’s was a constant struggle and he learned to use the camera and set up a photography studio in Penzance.

Around 1866 he returned to St Mary’s with his family and he was assisted in his photography by his sons Alexander and Herbert in the studio shed in the back garden of their home. Both Herbert and Alexander learned the art of photography at their father’s knee and Alexander was to become one of the most remarkable characters in Scilly. He had a passion for archaeology, architecture and folk history. He took endless pictures of ruins, prehistoric remains, and artefacts not just in Scilly but all over Cornwall.

Herbert by contrast was a quiet man, a competent photographer and a sound businessman. There can be no doubt that without his steadying influence, the business aspect of their photography might not have survived Alexander’s more flamboyant approach. Frank spent some time working for photographers in Cornwall learning about new technology. But Frank returned to Scilly in 1957 and worked in partnership with his father for two years.

After this time it was apparent that they could not work together and James retired to Cornwall and sold the business to Frank. Under Frank’s stewardship the business expanded. He produced postcards and sold souvenirs to supplement the photography, and opened another shop. Scilly is always in the news and there is always demand for pictures by the press.

James Gibson was, in fact, the most qualified of all the photographers. He was an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society and won various medals and awards through his lifetime. He was an adventurous photojournalist as well as a jobbing photographer. Today, the family runs a souvenir shop which sells books and postcards and they are currently digitising 150 years of photographs.”

“The family’s famous shipwreck photography began in 1869, on the historic occasion of the arrival of the first Telegraph on the Isles of Scilly. At a time when it could take a week for word to reach the mainland from the islands, the Telegraph transformed the pace at which news could travel. At the forefront of early photojournalism, John became the islands’ local news correspondent, and Alexander the telegraphist – and it is little surprise that the shipwrecks were often major news.

On the occasion of the wreck of the 3500-ton German steamer, Schiller in 1876 when over 300 people died, the two worked together for days – John preparing newspaper reports, and Alexander transmitting them across the world, until he collapsed with exhaustion. Although they often worked in the harshest conditions, travelling with hand carts to reach the shipwrecks – scrambling over treacherous coastline with a portable dark room, carrying glass plates and heavy equipment – they produced some of the most arresting and emotive photographic works of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.”

Text from Wills Robinson. “Gibson family’s photos chart a century of Cornish shipwrecks,” on the Mail Online website 21/10/2013

James Gibson at work

The Gibsons of Scilly

SS City of Cardiff

1912

21 March – City of Cardiff (United Kingdom) wrecked at Nanjizal, two miles south of Land’s End. The Sennen Life-Saving Apparatus Team took the crew off by breeches buoy. Citation: Corin, J.; Farr, G. (1983). Penlee Lifeboat. Penzance: Penlee & Penzance Branch of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. p. 120.

The steamer City of Cardiff pictured trapped on rocks with steam still coming out of the chimney, it was washed ashore by a strong gale in March 1912 at Nanjizel. The Captain, his wife and son, and the crew were all rescued but the vessel was left a total wreck. British ship built 1906, the City of Cardiff was en route from Le Havre, France, to Wales in 1912 when it was wrecked in Mill Bay near Land’s End. All of the crew were rescued.

The Gibsons of Scilly

SS City of Cardiff

191

The Gibsons of Scilly

SS City of Cardiff

1912

The Gibsons of Scilly

SS City of Cardiff

1912

The Gibsons of Scilly

SS City of Cardiff (detail)

1912

The Gibsons of Scilly

Brinkburn

1898

“The steamer Brinkburn, belonging to Messrs. Harris and Dixon, of London, from Galverton for Havre, with cotton, ran ashore on the Maiden Bower, Isles of Scilly, on Thursday at midnight during dense fog. The crew of 30 took to their lifeboats and landed in safety. The Brinkburn is a total wreck.” 15/12/1898

Bales of cotton were hauled onto the quayside at Hugh Town, St Mary’s from the wrecked cargo steamer Brinkburn in December 1898. It was travelling from Galveston, USA, to Le Havre when it grounded on the Maiden Bower rocks. The salvage ship Hyaena is alongside the pier on the left. The crew abandoned the ship and were guided to Bryher by islanders. The ship was submerged at high water and cotton was salvaged and landed at St Mary’s over several months.

The Gibsons of Scilly

SS Schiller

1875

SS Schiller was a 3,421 ton German ocean liner, one of the largest vessels of her time. Launched in 1873 she plied her trade across the Atlantic Ocean, carrying passengers between New York and Hamburg for the German Transatlantic Steam Navigation Line. She became notorious on 7 May 1875, when while operating on her normal route she hit the Retarrier Ledges in the Isles of Scilly, causing her to sink with the loss of most of her crew and passengers, totalling 335 fatalities.

Captain Thomas needed to slow due to poor visibility in thick sea fog as she entered the English Channel, and was able to calculate that his ship was in the region of the Isles of Scilly, and thus within range of the Bishop Rock lighthouse which would provide him with information about his position. To facilitate finding the islands and the reefs which surround them, volunteers from the passengers were brought on deck to try to find the light. These lookouts unfortunately failed to see the light, which they were expecting on the starboard quarter, when in fact it was well to port (nautical). This meant that the Schiller was sailing straight between the islands on the inside of the lighthouse, leaving the ship heading towards the Retarrier Ledges.

The Schiller grounded on the reef at 10pm, sustained significant damage, but not enough in itself to sink the large ship. The captain attempted to reverse off the rocks, pulling the ship free but exposing it to the heavy seas which were brewing, which flung the liner onto the rocks by its broadside three times, stoving in the hull and making the ship list dangerously as the lights died and pandemonium broke out on deck as passengers fought to get into the lifeboats.

It was at these boats that the real disaster began, as several were not seaworthy due to poor maintenance and others were destroyed, crushed by the ship’s funnels which fell amongst the panicked passengers. The captain attempted to restore order with his pistol and sword, but as he did so, the only two serviceable lifeboats were launched, carrying 27 people, far less than their full capacity. These boats eventually made it to shore, carrying 26 men and one woman.

On board the ship the situation only became worse, as breakers washed completely over the wreck. All the women and children on board, over 50 people, were hurried into the deck house to escape the worst of the storm. It was there that the greatest tragedy happened, when before the eyes of the horrified crew and male passengers, a huge wave ripped off the deck house roof and swept the occupants into the sea, killing all inside. The wreck continued to be pounded all night, and gradually those remaining on board were swept away or died from exposure to cold seas, wind and resulting hypothermia, until the morning light brought rescue for a handful of survivors.

The recognised manner of signalling disaster at sea was by the firing of minute guns, carried on all ships for signalling purposes. Unfortunately, it had become the custom in the islands to fire a minute gun as your ship passed safely through the area, and so the firing of the Schiller’s guns failed to produce hoped for rescue. Such an operation at night and in the dark would have been near impossible anyway with such high seas, and thus it was not until the first light that rescue craft began arriving.

St Agnes pilot gig, the O and M, was summoned to investigate multiple cannon shots. Her crew discovered the mast of the sinking Schiller. The O and M rowed to pick up five survivors before returning to St Agnes for assistance. Steamers and ferries from as far away as Newlyn, Cornwall, assisted the rescue operation.

Of her original 254 passengers and 118 crew, there were 37 survivors. The death toll, 335, made the disaster one of the worst in British history.

Text from the Wikipedia website

“An exceptional collection of shipwreck photographs taken by four generations of the Gibson family was bought at a Sotheby’s auction yesterday by the Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG) for £122,500 ($195,645) including buyer’s premium. The archive contains more than 1,100 glass plate negatives, more than 500 film negatives and 97 original print photographs of shipwrecks off the coasts of Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly. They make the perfect complement to the RMG’s pre-existing collection of historic maritime photography.

For 125 years, starting with patriarch John Gibson, a seaman who became a professional photographer in 1860, the Gibson family braved shoals, waves and sand to capture haunting scenes of shredded ships, dramatic rescues, cargo salvage and burials of people who fell victim to the treacherous coastal waters of southwest England. John’s sons Herbert and Alexander joined the business in 1865 and their talents would come to define the Gibson archive and its exceptional high quality. The first wreck they photographed was in 1869 when the telegraph had just arrived on the Isles of Scilly.

These were not simple point and shoot operations. It was dangerous, highly physical labour. On the occasion of the wreck of the 3500-ton German steamer, Schiller, in 1876 when over 300 people died, the two brothers worked together for days – [Herbert] preparing newspaper reports, and Alexander transmitting them across the world, until he collapsed with exhaustion. Although they were working in difficult conditions, travelling with a cart or boat to reach the shipwrecks – and scrambling over rocky crags and sand dunes with a portable dark room, carrying fragile glass plates and heavy equipment – they produced some of the most arresting and emotive photographic images of shipwrecks produced in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

They were pioneers. This was at a time when most photography was still firmly wedded to the studio portrait. The equipment was so bulky and fragile that climbing over crags hauling not just the camera and plates but a freaking dark room would be inconceivable to most people. That the Gibsons pulled it off is amazing in and of itself; that they also created images of such beauty and emotional resonance makes the archive little short of miraculous.

The Gibson family business is still going strong on the Isles of Scilly, although they’ve added souvenir and wholesale postcard sales to the professional photography. Sandra Gibson, John’s great-great granddaughter, runs it now with her husband Pete. The family decided it was time to sell the archive rather than let it continue to languish in boxes.”

Author John Le Carré, who used some Gibson photographs in his books, visited the business, then run by Frank, Sandra’s father, in 1997. I love his description of the archive:

“We are standing in an Aladdin’s cave where the Gibson treasure is stored, and Frank is its keeper. It is half shed, half amateur laboratory, a litter of cluttered shelves, ancient equipment, boxes, printer’s blocks and books. Many hundreds of plates and thousands of photographs are still waiting an inventory. Most have never seen the light of day. Any agent, publisher or accountant would go into free fall at the very sight of them.”

Now that National Maritime Museum has the pictures, we can all go into free fall at the very sight of them, and the family can be sure it will be archived properly and shared with the world. The museum plans to use the archive to study the dangers of the seafaring life and to display this invaluable record as widely as possible.”

Press release from the Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG)

The Gibsons of Scilly

River Lune

1879

River Lune struck in fog and at night just south of Annet (Scillies), July 27th, 1879 – the same day as the Maipu. The master later blamed a faulty chronometer, since he had believed himself fifteen miles to the west. The ship heeled and sunk aft in the first ten minutes. The crew took to their boats, but returned in daylight to collect their belongings. This barque was only eleven years old. She broke up soon afterwards.

John Fowles. Shipwreck. 1975

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Punta

1955

The Gibsons of Scilly

SV Seine

1900

The Gibsons of Scilly

SV Seine (detail)

1900

The French ship, the barque SV Seine (built in 1899) was on her way to Falmouth with a cargo of nitrate when she ran into a gale off Scilly on Decermber 28, 1900. She ran ashore in Perran Bay, Perranporth, Cornwall, but thankfully all crew members were rescued with Captain Guimper reported as the last man to leave the ship before she was broken up in the next flood tide.

Ran ashore in Perran Bay (Perranporth), December 28th, 1900. This beautiful ship was a French ‘bounty clipper’ – so called because a government subsidy to French ship-owners allowed them to build for elegance rather than more mundane qualities. The crew got off in heavy seas. By dawn the next day she was dismasted and on her beam-ends, and broke up on the next flood-tide. Two weeks later the hulk of this celebrated barque was bought for only £42.

The Gibsons of Scilly

SV Albert Wilhelm

1886

SV Albert Wilhelm 1886, a German brig was lost 16 October 1886 Lelant.

The Albert Wilhelm, Lelant, 1886, a 202 ton German Brig travelling from the Isle of Man to Fowey.

The Gibsons of Scilly

MV Cita

1997

The German owned 300ft merchant vessel the Cita, sunk after it pierced its hull and ran aground in gale-force winds en route from Southampton to Belfast in March 1997. The mainly Polish crew of the stricken vessel were rescued a few hours after the incident by the RNLI and the wreck remained on the rock ledge for several days before slipping off into deeper water.

On 26 March 1997, the 300-ft merchant vessel MV Cita pierced its hull when running aground on rocks off the south coast of the Isles of Scilly in gale-force winds en route from Southampton to Belfast. The incident happened just after 3 am when the German-owned, Antiguan-registered 3,000 tonne vessel hit Newfoundland Point, St Mary’s. The mainly Polish crew of the stricken vessel were rescued a few hours after the incident by St Mary’s Lifeboat, RNLB Robert Edgar with the support of a H-3 Sea King rescue helicopter from RNAS Culdrose. They sailed to the UK mainland on board the Scillonian III later that afternoon. Many containers were washed up on the rocks and beaches of the Isles of Scilly, and many were found in the Celtic Sea, travelling as far as Cornwall.

Text from the Wikipedia website

The Gibsons of Scilly

The Glenbervie

1902

The Glenbervie, which was carrying a consignment of pianos and high quality spirits crashed into rocks Lowland Point near Coverack, Cornwall, in January 1902 after losing her way in bad weather. The British owned barque was laden with 600 barrels of whisky, 400 barrels of brandy and barrels of rum. All 16 crewmen were saved by lifeboat.

The Glenbervie, The Lizard, 1902, travelling from the Thames to West Africa spirits and pianos. Struck on the Manacles and went aground near Lowland Point, December 1901. The crew were saved in heavy seas by the Coverack lifeboat. The old wreckers must have groaned in their uneasy graves when they heard that this cargo was officially salvaged, since it contained over a thousand cases and barrels of spirits. There was also a valuable consignment of grand pianos on board, which were all ruined. The Glenbervie was launched in 1866; she was first a tea-clipper, then had many years in the Canada trade. She normally made three trips a year, between the thawing and the freezing of the St Lawrence, on this latter run.

The Gibsons of Scilly

SV Granite State / Slate

1895

American three-masted sailing ship built in 1877 ran aground near Porthcurno 4th November 1895.

On 3rd November 1895 this American sailing ship arrived in Falmouth with a cargo of wheat from the River Plate. Given orders to discharge in Swansea she sailed on the 4th November and whilst attempting to round Lands End, struck the Lee Ore rock of the Runnel Stone. Taken in tow by the Cardiff tug Elliot and Jeffrey she was beached in the shallows of Porthcurno. She rapidly settled, and when the wheat began to swell and the hatches burst under the pressure, she was abandoned. She broke up soon afterwards in a winter gale.

Struck on the Runnel Stone, three miles south-east of Land’s End, November 4, 1895. This fine Yankee windjammer was making for Swansea from Falmouth. A navigation error by the mate seems to have been the cause of disaster. She was hauled off by a tug, but had to be towed to the nearest sandy bay, Porthcurno. She settled rapidly, and when the cargo of wheat began to swell the crew took to boats. The Granite Slate was soon afterwards destroyed completely by a gale.

The Gibsons of Scilly

SV Granite State / Slate (detail)

1895

The Gibsons of Scilly

Hansy

1911

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

Wreck of the Norwegian full-rigger Hansy, Housel Bay, The Lizard, Cornwall, November 1911.

3 November – 1497 ton sailing ship Hansy (Norway) of Fredrikstad was wrecked at Housel Bay on the eastern side of the Lizard. Three men were saved by the Lizard lifeboat (Royal National Lifeboat Institution) and the rest along with the Captain’s family were taken off by rocket apparatus. She was bound for Sydney with building material and her cargo of steel and timber was washed up for weeks afterwards and used in many of the local cottages. One in Church Cove now bears her name. (Wikipedia)

“Wrecked in Housel Bay near the Lizard Point, November 13th, 1911. Sailing from Sweden to Melbourne with timber and pig-iron, she missed stays while trying to come about in a gale. The crew were brought ashore by breeches-buoy. Two days later a salvage party boarded – to find a pair of goats lying happily in a seaman’s bunk. Local fishermen did a thriving trade in timber for weeks afterwards; and the iron pigs are fished up for ballast to this day. The Scottish-built Hansy (formerly Aberfoyle) had had an unhappy history. In 1890 the bulk of the crew jumped ship in Australia, after a bad voyage out – only to be returned on board following a fortnight in jail. Jail must have been more agreeable, for eight men jumped ship again at the next port of call. In 1896 a steamer found the Aberfoyle drifting helplessly off Tasmania. The captain had been swept overboard, the first mate had committed suicide by leaping into the sea and the rest had given up hope. Similar stories of low morale – and often of insane bitterness between officers and crew – are manifold.”

John Fowles. Shipwreck. 1975

The Gibsons of Scilly

Voorspoed

1901

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

Horses and carts and a big crowd surround the Dutch three-masted schooner Voorspoed which ran aground in heavy weather on Perranporth Beach in March 1901. It was on passage from Cardiff to Bahia, Brazil, heavily laden with coal and machinery. The rocket brigade rescued the seven crew and one cabin boy. The captain was reluctant to leave but did so eventually. The cargo was salvaged during the afternoon although the captain though it was more like looting. He is reputed to have said: ‘I have been wrecked in different parts of the globe, even in the Fiji Islands, but never among such savages as those of Perranporth.’ The ship was refloated on the next tide.

The Gibsons of Scilly

Hampton

1909

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

Steam cargo ship Plympton ran aground at Lethegus Rocks, off St Agnes, Isles of Scilly, in foggy weather in August 1909. Islanders in seven gigs are salvaging cargo. The ship, on passage from Rosario to Falmouth with a cargo of maize, slipped off the rocks and rolled over onto its port side and two islanders were drowned.

The 2869-ton steamer Plympton was built by Furness Withy in West Hartlepool. The single-screw ship was powered by three-cylinder triple-expansion engines with two boilers giving her 256hp. She was 314ft long with a beam of 40ft.

She was captained by Alexander Stewart with a crew of 24 and one passenger when she called at Falmouth from Rosario, Argentina. There she received orders to take her cargo of 4100 tons of maize in bags on to Dublin and discharge it there.

At midnight on 13 August, 1909, she ran into dense fog that lasted throughout the following day. Stewart knew he was in trouble. The lead was used at short intervals and the siren sounded almost continuously. From 4am on 14 August, Captain Stewart set up a listening watch, with all hands on deck striving to hear the Bishop Rock foghorn. They still hadn’t heard it when the Plympton ran on to Lethegus Reef, filled with water and was abandoned. The crew and passengers landed safely on St Agnes.

Once the islanders were satisfied that all were safe, they set about the ancient Scilly practice of stripping the wreck, which they found hard aground by the bow. However, while they worked the Plympton rose with the flood tide and, without warning, capsized and sank. Two men who were below were drowned.

Anonymous. “The Hathor & The Plympton (Wrecks),” on the Wikimapia website [Online] Cited 21/10/2022

The Gibsons of Scilly

King Cadwallon

July 22, 1906

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

On the foggy morning of July 22, 1906, King Cadwallon struck rocks off the coast of St Martin’s Island. A photographer from the Gibson family boarded a rowboat to get this image before the ship sank completely beneath the waves.

The Gibsons of Scilly

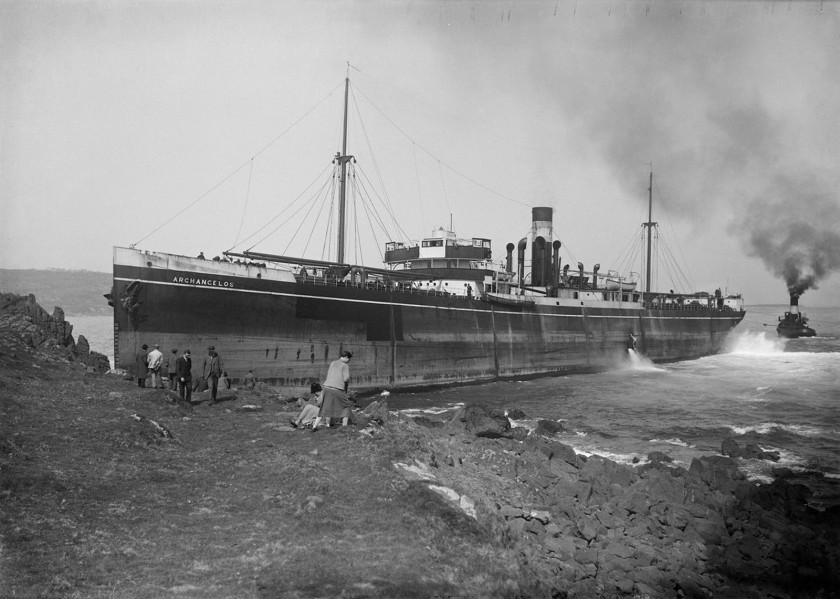

SS Archangelos

1929

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

A port bow view of the stranded cargo ship Archangelos (built 1918) with tugs in attendance and people watching from the shore.

The Greek cargo, Archangelos, owned by Livanos, ran aground in heavy fog at Coverack on April 22nd, 1929. Many attempts were made in vain to tow her off the rocks. Eventually they succeeded and the vessel was repaired and became the SS K. Sadikoglu.

The Gibsons of Scilly

Maurice Bernard

1921

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

A starboard bow view from the beach of the French general cargo vessel Maurice Bernard (1921) aground, with crowds watching the rescue of a man suspended from the wire leading from the ship to the shore. On passage Le Havre to Barry in ballast, went aground during a south-west gale. Later refloated with the aid of tugs.

The Gibsons of Scilly

Jebba

1907

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

The Jebba, seen from the cliffs of Bolt Tail, near Hope Cove, Devon, was on its way from Nigeria and the Gold Coast when it ran aground in thick fog in March, 1907. Lines stretch from the ship to the cliffs where the Breeches Buoy system was used to rescue 155 passengers and crew, at least one chimpanzee and three monkeys.

Built originally as the Albertville in 1896 by Sir Robert Dixon and Company, she was later taken over by the Elder Dempster line and renamed the Jebba. 302 feet long and 3813 tons gross, the Jebba was homeward bound from Sierra Leone carrying a cargo of rubber, ivory and fresh fruit worth over ?00,000. Besides this cargo she was also carrying 155 passengers and crew, and the Royal Mail.

In the early hours of 18 March 1907 the Jebba overshot the Eddystone in dense fog and ran aground under the steep cliffs at Whitchurch, just a few yards away from Bolt Tail. The ship immediately started to take in water, and after sending up distress rockets, the Captain ordered all the boiler fires to be doused to prevent the risk of an explosion. Being broadside onto the rocks, waves soon started breaking over the liner’s decks, but instead of the usual panic, the passengers and crew remained exceptionally calm, and all went dutifully to their lifeboat stations to await the Captains orders. Very quickly the Hope Cove lifeboat, which was literally around the corner, came upon the scene and because it could not get into the comparatively sheltered water between the Jebba and the shore, it was considered too dangerous to attempt to take people off from the weather side as it would mean cragging all 155 people through the rough seas. However, with the aid of a rocket apparatus and the extraordinary bravery of two local men all the passengers and crew were eventually saved.

In order to get the rescue started, Issac Jarvis and John Argeat climbed down the treacherous 200 foot cliffs in complete darkness to set up a bosun’s chair, with which they rescued over a hundred persons. So impressed was everybody by their selfless bravery that King Edward VII personally approved that the men be awarded the Board of Trade Bronze Medal. They were also awarded the Liverpool Shipwreck and Humane Society Silver Medal…

Soon after the rescue the Jebba filled with water, and although most of the cargo was eventually salvaged, it was obvious that the liner was a complete write off. Once again Bolt Tail had claimed another victim.

Peter Mitchell. “The Wreck of the Jebba,” on the Submerged website Nd [Online] Cited 22/10/2022

The Gibsons of Scilly

Horsa

1893

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

Three-masted cargo ship Horsa ran aground in Bread and Cheese Cove (Loop Hole), St Martin’s in April 1893. Two RNLI lifeboats are alongside the ship with rowing gigs, transferring people to or from the ship which was on passage from New Zealand with a cargo of tinned meat, wool and grain and picked up a pilot off Round Island, Scilly. The ship was towed out of the cove by the packet steamer Lyonesse but it rolled over and the crew were rescued before Horsa sank.

An elevated starboard bow view of the three-masted cargo ship Horsa (1860) aground in Bread and Cheese Cove (Loop Hole), St. Martin’s, Isle of Scilly. The tide has dropped enough for the waterline of the ship to be exposed and water can be seen being pumped out. The RNLI lifeboat (possibly the Henry Dundas or James & Caroline) is off the starboard side under oar. Four rowing gigs are alongside the hull. People are standing on the upper deck leaning over the bulwarks. The photographer was standing on the cliffs above the cove looking northeast towards St. Martin’s Head and the red and white striped 17th Century day marker on the headland.

The Horsa (built 1860) was on passage from New Zealand with a cargo of tinned meat, wool and grain and picked up a pilot off Round Island, Scilly. According to the report in the newspaper after the Board of Inquiry, the pilot allowed the ship to stand on port tack too long before deciding that they would not pass Hard Lewis Rocks. The attempt to tack northward failed as the light winds and the tide caused the ship to miss her stays (i.e. could not get the bow through the wind quick enough). The ship was run aground in Bread and Cheese Cove to save it and the crew [Liverpool Mercury, 27 April 1893]. The ship was towed out of the cove by the packet steamer Lyonesse and eventually the captain sailed Horsa after three tow lines snapped. The ship rolled over and sank in the early hours of 5 April 1893. The Lyonesse rescued the remaining crew before Horsa sank.

Text from the Royal Museums Greenwich website

The Gibsons of Scilly

Renwick

1903

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

NB. The shutter speed must have been between a quarter and a half a second to get the movement of the people on the beach.

In February 1903, the Renwick was in ballast when it was dragged onto Castle Beach in Falmouth Bay during a south-westerly gale. A month later the ship was floated off and towed into Falmouth Harbour and later was sold after temporary repairs.

An elevated starboard bow view of the cargo steamer Renwick (1890) stranded on Castle Beach in Falmouth Bay. A large number of people are on the beach and rocks off the ship’s starboard side as the tide is out. The rudder has broken away from the stern post at the bottom. The photographer was standing near Cliff Road looking across the wreck to the southeast towards Pendennis Castle and Pendennis Point in the background.

On 26 February 1903, the Renwick was in ballast when it dragged ashore on Castle Beach in Falmouth Bay during a south-westerly gale. On 11 March 1903 the ship was floated off and towed into Falmouth Harbour [Dundee Courier, 12 March 1903]. The ship later was sold and after temporary repairs was taken to Cardiff to be repaired in Mount Stuart Dry Dock, arriving on Monday 6 April 1903 [Western Mail, 7 April 1903].

Text from the Royal Museums Greenwich website

The Gibsons of Scilly

Busby

1894

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

Busby left Newport on its maiden voyage for Civita Vecchia on June 22, 1894 with a cargo of 4,600 tons of coal and 26 crew. It ran aground two days later in thick fog at Pendeen Cove.

A port quarter view of the general cargo steamer Busby (1894) aground with a slight list to starboard in Pendeen Cove (near Portheras Cove). The photographer was standing on the cliffs above Pendeen Cove looking north-west towards The Wra or Three Stone Oar rocks in the background. A man dressed in white with his back to the camera is standing on the rocky shoreline holding a line that is attached to a pulley block on the guardrail of the Busby. A small rowing boat is tied alongside the ship near a rope ladder.

Busby left Newport on its maiden voyage for Civita Vecchia on 22 June with a cargo of 4,600 tons of coal and 26 crew. It ran aground on 24 June 1894 in thick fog. However, after the cargo was removed, and pumps installed the ship was refloated, only to founder under tow on 16 July 1894.

Text from the Royal Museums Greenwich website

The Gibsons of Scilly

Ravonia

1911

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

Sightseers turn out to see the three-masted schooner Ravonia aground off St Ives Head in 1908. She was later re-floated and towed to Liverpool for repairs

A port side view, fine of the port bow, of the steel screw three-masted collier Ravonia (1908) stranded on shore near St Ives Head. A number of men and children are around the bows of the ship. The tide is out, so water is washing around the stern to the funnel area of the hull only. The Ravonia was stranded near St Ives Head on 1 July 1911. The master was found to be responsible for steaming too close to land in foggy weather and not using the lead [The Times report, 17 July 1911].

Text from the Royal Museums Greenwich website

The Gibsons of Scilly

Cviet

1884

Glass negative

Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection

A large group gathers to see Austrian wooden sailing barque Cviet, aground on Porthleven beach in January 1884. The vessel was bound from St Domingo to Falmouth with a cargo of about 600 tons of logwood when it was caught in hurricane force winds. Rocket lines were fired to reach the crew, but eventually a fisherman swam through the surf and threw a line. The captain and one of the crew were washed overboard and drowned. The rest of the crew were saved.

An elevated starboard quarter view of the Austrian wooden sailing barque Cviet (1870) aground on Porthleven beach listing to port. The tide is out and the waves are breaking lower down on the beach. The top masts are missing and the rigging is a mess. A large group of people are off the starboard side on the beach close to the stern and quarter, many looking at the camera. Part of the Porthleven pier is in the background.

The Cviet was bound from St. Domingo to Falmouth for orders with a cargo of about 600 tons of logwood. On 26 January 1884 the ship was caught in hurricane force winds that blew most of her sails. Cviet was driven ashore on Porthleven beach broadside to the waves. Rocket lines were fired to reach the crew, but eventually a fisherman swam through the surf and threw a line. The captain and one of the crew were washed overboard and drowned. The rest of the crew were saved. The rigging was taken down on 27 January at low water and the salvage operations continued under the direction of the Receiver of Wreck. [Royal Cornwall Gazette, 1 February 1884]

Text from the Royal Museums Greenwich website

Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG)

The National Maritime Museum, Queen’s House, Royal Observatory and Cutty Sark are normally open 10.00-17.00 seven days a week.

You must be logged in to post a comment.