Exhibition dates: 31st July – 8th November, 2015

Melbourne Winter Masterpieces 2015

Curator: Dr. Mikhail Dedinkin, curator from the State Hermitage Museum supported by NGV Director Tony Ellwood and Dr. Ted Gott, Senior Curator of International Art at the NGV

Hermitage Museum, the Winter Palace in Winter, St Petersburg

Photo: Pavel Demidov

Some beauty to cheer me up from my sickbed.

These are the official press photographs for the exhibition Masterpieces from the Hermitage: The Legacy of Catherine the Great. To see my installation photographs of the exhibition go to this posting.

The paintings look as fresh today as when they were first painted, some of them in the early 1500s. To see the thumbs up gesture in Diego Velázquez’s Luncheon (c. 1617-1618, below) echoing down the centuries, is worth the price of admission alone.

We cannot imagine what life would have been like back then… no medication, rampant disease and malnutrition, little law enforcement with danger lurking around each turn (see Matthew Beaumont. Night Walking: A Nocturnal History of London, Chaucer to Dickens. London and New York: Verso, 2015).

And yet these talented artists, supported by the elite, produced work which still touches us today.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Many thankx to the National Gallery of Victoria for allowing me to publish the art works in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the art works. See Part 1 of the posting.

Chinese

Cup

early 17th century

Silver, enamel

4 x 3 x 7cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ЛС-133, ВВс-250)

Acquired before 1789

Chinese

Teapot with lid

17th century

Silver, enamel

18.0 x 5.5cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ЛС-80 а, б, ВВс-219)

Acquired before 1789

Sèvres Porcelain Factory

Sèvres (manufacturer) France est. 1756

Cameo Service

1778-1779

Porcelain (soft-paste), gilt

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg Commissioned by Catherine ll as a gift for Prince Grigory Potemkin in 1777; Potemkin’s Taurida Palace, St Petersburg from 1779; transferred to the Hofmarshal’s Office of the Winter Palace after his death; 1922 transferred to the State Hermitage Museum

Grand Duchess Maria Fyodorovna (Russian, 1795-1828) (engraver)

Russia (manufacturer)

Catherine the Great as Minerva

1789

Cameo

Jasper, gold

6.5 x 4.7cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. К 1077)

Acquired 1789

James Tassie, London (England, 1735-1799) (workshop of)

Head of Medusa

1780s

Coloured glass, gilded paper

7.6 x 9.2cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. R-T, 3296 a)

Purchased from James Tassie 1783-88

Chinese

Toilet service

early 18th century

Glass, mercury amalgam, paper, silver, filigree, parcel-gilt, wood, velvet, peacock and king-fisher feathers, mother-of-pearl, crystals

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ЛС-472/ 1,2, ВВс-373)

Chinese

Table decoration in the form of a pair of birds

1740s-50s

Silver, enamel, silver-gilt

26.0 x 26.0 x 15.0cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ЛС-26, ВВс-189)

Chinese

Crab-shaped box on a leaf tray

1740s-50s

Silver, enamel, silver-gilt

(a) 4.0 x 14.0 x 13.0cm (box)

(b) 3.0 x 22.0 x 17.0cm (stand)

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ЛС-9 а,б, ВВс-186)

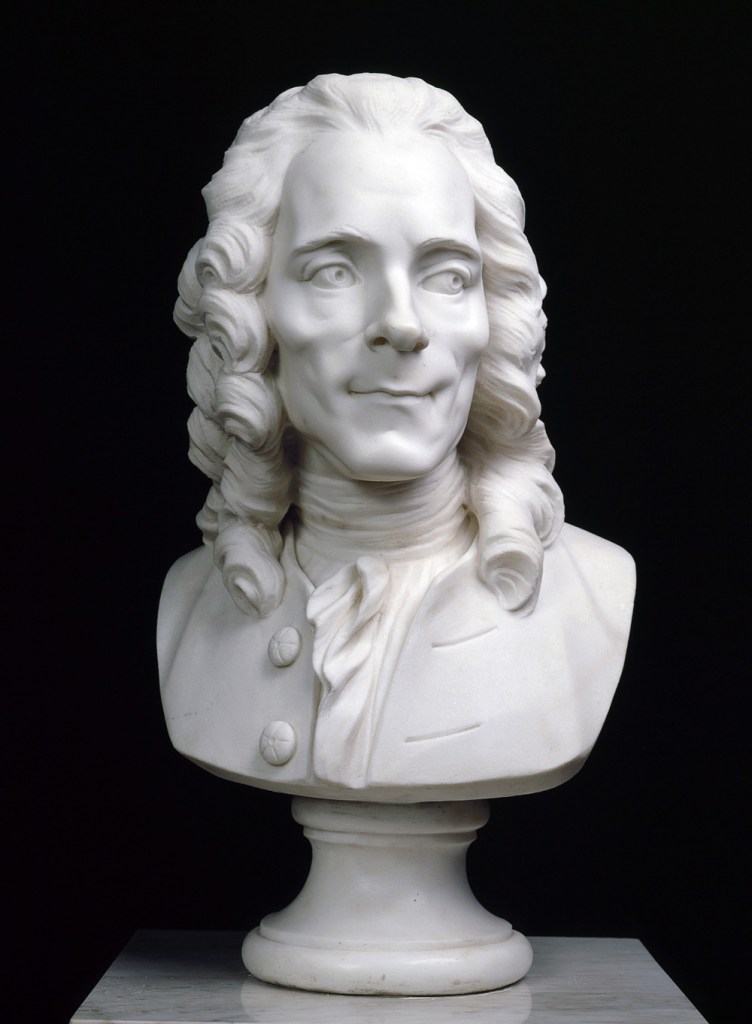

Marie-Anne Collot (French, 1748-1821)

Voltaire

1770s

Marble

49 x 30 x 28cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. Н.ск. 3)

Acquired from the artist, 1778

Jean-Antoine Houdon (French, 1741-1828)

Catherine II

1773

Marble

90 x 50 x 32cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. Н.ск. 1676)

Transferred from the Stroganov Palace, Leningrad, 1928

Jean-Baptiste Greuze (French, 1725-1805)

Head of an old man. Study for The paralytic

1760s

Red and black chalk

49.3 x 40cm (sheet)

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ОР-14727)

Acquired from the artist in 1769 for the Museum of the Academy of Arts. Transferred to the Hermitage in 1924

François Boucher (French, 1703-1770)

Study of a female nude

1740

Red, black and white chalk on brown paper

26.2 x 34.6cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ОР-382)

Acquired from the collection of Count Cobenzl, Brussels, 1768

Charles-Louis Clérisseau (French, 1721-1820)

Design for the paintings in the cell of Father Lesueur in the Monastery of Santissima Trinità dei Monti in Rome

1766-1768

Pen and black and brown ink, brown and grey wash

36.9 x 53cm (sheet)

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ОР-2597)

Acquired from the artist by Catherine II on 5 May 1780, Provenance: before 1797

Carlo Galli-Bibiena (Austrian, 1728-1787)

Design for the interior decoration of a library

1770s

Pen and ink, grey wash and watercolour over pencil

32 х 44cm (sheet)

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ОР-231)

Acquired before 1797

Giacomo Quarenghi (Italian, 1744-1817)

Façade of the Hermitage Theatre

1780s

Pen and ink, watercolour

33 х 47cm (sheet)

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ОР-9626)

Acquired from Giulio Quarenghi in 1818

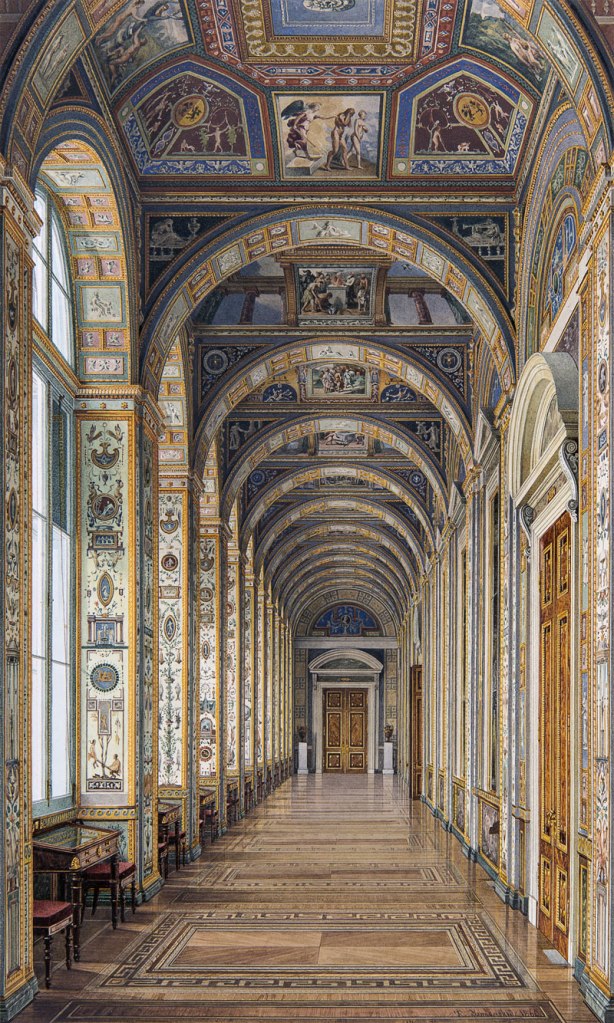

Konstantin Ukhtomsky (Russian, 1818-1881)

The Raphael Loggia

1860

Watercolour

42 х 25cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ОР-11741)

Acquired from the artist, 1860

Over 500 works from the personal collection of Catherine the Great will travel to Australia in July. Gathered over a 34-year period, the exhibition represents the foundation of the Hermitage’s collection and includes outstanding works from artists such as Rembrandt, Velasquez, Rubens and Titian. Exemplary works from Van Dyck, Snyders, Teniers and Hals will also travel, collectively offering some of the finest Dutch and Flemish art to come to Australia. The exhibition, presented by the Hermitage Museum, National Gallery of Victoria and Art Exhibitions Australia, is exclusive to Melbourne as part of the Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series.

The Premier of Victoria, the Hon. Daniel Andrews MP said: “Masterpieces from the Hermitage: The Legacy of Catherine the Great will showcase treasures from one of the largest, oldest and most visited museums in the world. Another major event for Melbourne, this exhibition will provide visitors with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see first-hand the extraordinary personal collection of Catherine the Great, drawn from the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.”

NGV Director, Tony Ellwood said, “This exhibition celebrates the tenacity and vision of a true innovator in the arts. Catherine the Great’s inexhaustible passion for the arts, education and culture heralded a renaissance, leading to the formation of one of the world’s great museums, the Hermitage.”

“We are delighted that we have the good fortune of bringing one of the world’s most important collections to Australian audiences. The exhibition is a rare opportunity to be immersed in the world of Catherine the Great and her magnificent collection of art,” Tony Ellwood said.

Catherine the Great’s reign from 1762 to 1796 was known as the golden age and is remembered for her exceptional patronage of the arts, literature and education. Of German heritage, Catherine the Great was well connected in European art and literature circles. She saw herself as a reine-philosophe (Philosopher Queen), a new kind of ruler in the Age of Enlightenment. Guided by Europe’s leading intellectuals, such as the French philosophers Voltaire and Diderot, she sought to modernise Russia’s economy, industry and government, drawing inspiration both from classical antiquity and contemporary cultural and political developments in Western Europe.

A prolific acquirer of art of the period, Catherine the Great’s collection reflects the finest contemporary art of the 18th century as well as the world’s best old masters of the time, with great works by French, German, Chinese, British, Dutch and Flemish artists. Notable in this exhibition are entire groups of works acquired from renowned collections from France, Germany and England representing the best collections offered for sale at the time. The exhibition will feature four Rembrandts, including the notable Young woman with earrings, known as one of most intimate images Rembrandt ever created. The exhibition will also include 80 particularly fine drawings by artists including Poussin, Rubens, Clouet and Greuze.

Exquisite decorative arts will be brought to Australia for this exhibition, including 60 items from the Cameo Service of striking enamel-painted porcelain made by the Sèvres Porcelain Manufactory in Paris. Commissioned by Catherine the Great for her former lover and military commander, Prince Grigory Potemkin, the dinner service features carved and painted imitation cameos, miniature works of art, based on motifs from the French Royal collection.

Director of the Hermitage Museum, Mikhail Piotrovsky said, “These outstanding works from the personal collection of Catherine the Great represent the crown jewels of the Museum. It was through the collection of these works and Catherine the Great’s exceptional vision that the Hermitage was founded. Today it is one of the most visited museums in the world. We are very pleased to be able to share these precious works with Australian audiences at the 250-year anniversary of this important institution.”

Catherine the Great’s love of education, art and culture inspired a period of enlightenment and architectural renaissance that saw the construction of the Hermitage complex. This construction includes six historic buildings along the Palace Embankment as well as the spectacular Winter Palace, a former residence of Russian emperors. On view in the exhibition will be remarkable drawings by the Hermitage’s first architects Georg Velten and Giacomo Quarenghi, complemented by excellent painted views of the new Hermitage by Benjamin Patersen. These, along with Alexander Roslin’s majestic life-size portrait of Catherine, set the scene for a truly spectacular exhibition.

Visitors to the exhibition will be able to immerse themselves in Catherine the Great’s world evoking a sensory experience of a visit to the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg. The exhibition design will have rich treatments of architectural details, interior furnishings, wallpapers and a colour palette directly inspired by the Hermitage’s gallery spaces. Enveloping multimedia elements will give visitors a sense of being inside the Hermitage, evoking the lush and opulent interiors.

The Hermitage Museum was founded in 1764 by Catherine the Great and has been open to the public since 1852. With 3 million items in its holdings, the Hermitage is often regarded as having the finest collection of paintings in the world today. In 2014, The Hermitage celebrated its 250-year anniversary and opened a new wing of the museum with 800 rooms dedicated to art from the 19th to 21st centuries. The exhibition is organised by The Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg in association with the National Gallery of Victoria and Art Exhibitions Australia.

Masterpieces from the Hermitage: The Legacy of Catherine the Great will be at NGV International from 31 July – 8 November 2015 and will be presented alongside the David Bowie is exhibition at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image as part of the 2015 Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series.

Press release from the National Gallery of Victoria

Jean-Baptiste Santerre (French, 1651-1717)

Two actresses

1699

Oil on canvas

146 х 114cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-1284)

Acquired 1768

Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641)

Portrait of Philadelphia and Elizabeth Wharton

1640

Oil on canvas

162 х 130cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-533)

Acquired from the collection of Sir Robert Walpole, Houghton Hall, 1779

Jean Louis Voille (French, 1744-1804)

Portrait of Olga Zherebtsova

1790s

Oil on canvas

73.5 х 58cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-5654)

Acquired from the collection of E. P. Oliv, Petrograd, 1923

Peter Paul Rubens and workshop (Flemish, 1577-1640)

The Apostle Paul

c. 1615

Oil on wood panel

105.6 х 74cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-489)

Acquired before 1774

Leonardo Da Vinci (school of)

Female nude (Donna Nuda)

Early 16th century

Oil on canvas

86.5 х 66.5cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-110)

Acquired from the collection of Sir Robert Walpole, Houghton Hall, 1779

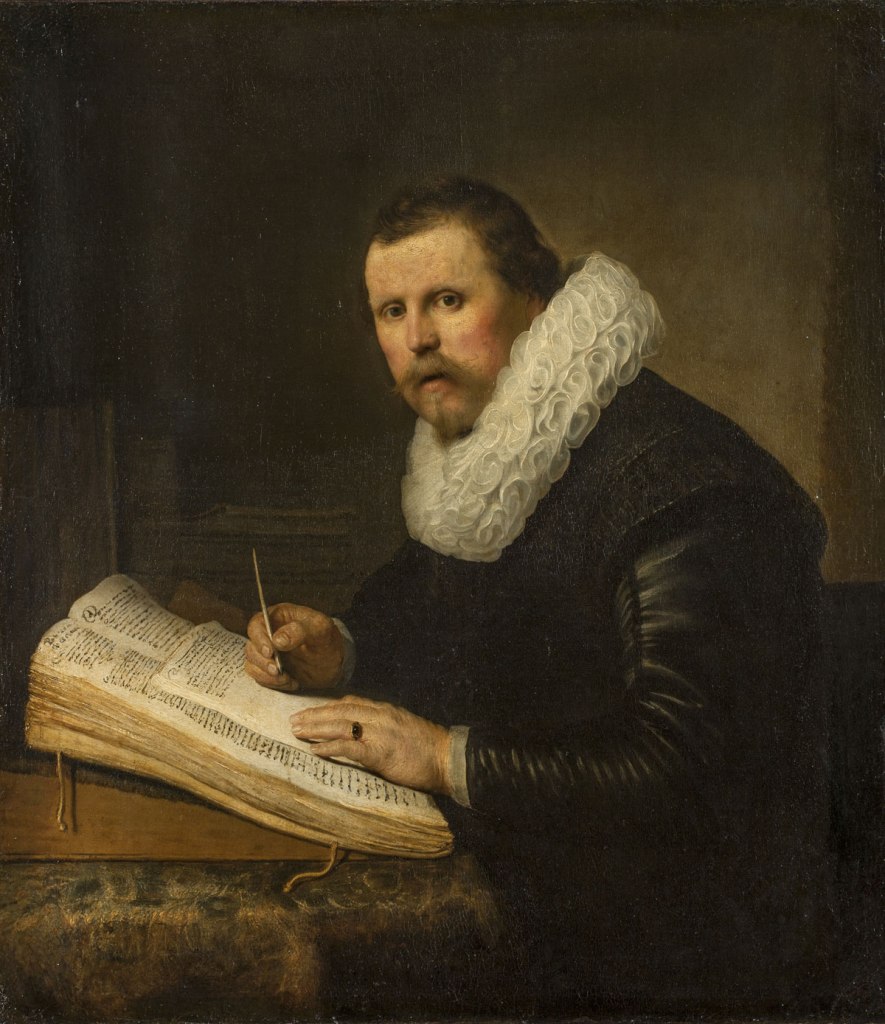

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Portrait of a scholar

1631

Oil on canvas

104.5 х 92cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-744)

Acquired from the collection of Count Heinrich von Brühl, Dresden, 1769

Jean-Baptiste Perronneau (French, 1715-1783)

Portrait of a boy with a book

1740s

Oil on canvas

63.0 х 52cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-1270)

Acquired from the collection of A. G. Teplov, St Petersburg, 1781

Domenico Capriolo (Italian, c. 1494-1528)

Portrait of a young man

1512

Oil on canvas

117 х 85cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-21)

Acquired from the collection of Baron Louis-Antoine Crozat de Thiers, Paris, 1772

Alexander Roslin (Swedish, 1718-1793)

Portrait of Catherine II

1776-1777

Oil on canvas

271 х 189.5cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-1316)

Acquired from the artist, 1777

Titian (Italian, 1485-1490 – 1576)

Portrait of a young woman

c. 1536

Oil on canvas

96 х 75cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-71)

Acquired from the collection of Baron Louis-Antoine Crozat de Thiers, Paris, 1772

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669)

Young woman trying on earrings

1657

Oil on wood panel

39.5 х 32.5cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-784)

Acquired from the collection of the Comte de Baudouin, Paris, 1781

Francois Clouet (French, c. 1516-1572)

Portrait of Charles IX

1566

Black and red chalk

33.1 x 22.5cm (sheet)

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. OР-2893)

Acquired from the collection of Count Cobenzl, Brussels, 1768

David Teniers II (Flemish, 1610-1690)

Kitchen

1646

Oil on canvas

171 х 237cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-586)

Acquired from the collection of Sir Robert Walpole, Houghton Hall, 1779

Cornelis de Vos (Dutch/Flemish, c. 1584-1651)

Self-portrait of the artist with his wife Suzanne Cock and their children

c. 1634

Oil on canvas

185.5 х 221cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-623)

Donated by Prince G. A. Potemkin, 1780s

Anthony van Dyck (Flemish, 1599-1641)

Family portrait

c. 1619

Oil on canvas

113.5 х 93.5cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-534)

Acquired from a private collection, Brussels, 1774

Charles Vanloo (French, 1705-1765)

Sultan’s wife drinking coffee

1750s

Oil on canvas

120 х 127cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-7489)

Acquired from the collection of Madame Marie-Thérèse Geoffrin, Paris, 1772

Peter Paul Rubens and workshop (Flemish, 1577-1640)

The Adoration of the Magi

c. 1620

Oil on canvas

235 х 277.5cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. № ГЭ-494)

Acquired from the collection of Dufresne, Amsterdam, 1770

Diego Velázquez (Spanish, 1599-1660)

Luncheon

c. 1617-1618

Oil on canvas

108.5 х 102cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-389)

Acquired 1763-1774

Melchior d’Hondecoeter (Dutch, 1636-1695)

Birds in a park

1686

Oil on canvas

136 х 164cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-1042)

Acquired from the collection of Jacques Aved, Paris, 1766

Frans Snyders (Flemish, 1579-1657)

Concert of birds

1630-1640

Oil on canvas

136.5 х 240cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg (Inv. no. ГЭ-607)

Acquired from the collection of Sir Robert Walpole, Houghton Hall, 1779

NGV International

180 St Kilda Road

Opening hours for exhibition

10am – 5pm daily

You must be logged in to post a comment.