Exhibition dates: 28th October, 2025 – 15th February, 2026

Curator: Marie Robert, Chief Curator, photography and cinema Musée d’Orsay

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Peppino Scossa endormi dans les bras de sa mère, 11 août 1888

(Peppino Scossa asleep in his mother’s arms, August 11, 1888)

1888

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

8.7 x 11.7cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Amour fou, amour tu

This is one of those unheralded exhibitions on a photographer that you may never have heard of that Art Blart likes to promote.

Gabrielle Hébert as she became, married the painter Ernest Hébert in 1880. She was 28, he was 63. From 1888 until his death in 1908 at the age of 91, she documented her husband painting, their surroundings and their affluent, upper class social milieux. And then she stopped, she gave up photography, she lost the amour fou, that incredible passion that had driven her for so many years to take photographs.

While “her photographs provide an intimate look into the artistic life of the time, portraying artists, models, and domestic scenes” they also do something more – they represent the viewpoint of a female artist which challenges the masculine conventions of the day. “Overturning gender stereotypes, she watched him obsessively and was never tired of capturing him on film… Thanks to her images, which she shared and exchanged with her friends and family, she became recognised as an auteur and gained social status in a milieu where artistic creation was the preserve of men.” (Text from the Musée d’Orsay website)

Further, from my point of view, Gabrielle Hébert was not an amateur photographer taking snapshots for her “visual diary” but an artist fully conversant with current trends in photography. While there are the standard documentary photographs of sculptures and Ernest Hébert and friends painting … there is so much more!

Photographs such as the allegorical Peppino Scossa endormi dans les bras de sa mère, 11 août 1888 (Peppino Scossa asleep in his mother’s arms, August 11, 1888) (1888, above) and La duchesse de Mondragone et l’une de ses bellessoeurs posent pour une Annonciation, juin 1890 (The Duchess of Mondragone and one of her sisters-in-law pose for an Annunciation, June 1890) (1890, below) are redolent of the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron (British born India, 1815-1879).

Other photographs such as Lys des parterres, juin 1890 (Flowerbed lilies, June 1890) (1890, below) evidence her consummate skill at capturing the perfume of a place whilst images such as Procession sur le port de Brindisi (Pouilles) (Procession in the port of Brindisi (Apulia)) (1893, below) show her ability to picture the informality of large groups of people and the atmosphere of the scene.

Then there are the joyous highs of a modern woman looking at the world with perceptive eyes. In the photograph Amalia Scossa et Ernest Hébert à sa peinture La Vierge au chardonneret sur la terrasse du campanile (around 1891, below), Gabrielle Hébert was not afraid to dissect the pictorial plane with strong verticals, horizontal and diagonal lines, providing the viewer with the feeling of an almost voyeuristic in-sight into the creative scene, each section of the photograph holding out attention – two chairs, one upturned on the other, supporting the umbrella shielding the painter from the sun; the Virgin and her child filling the distant space; the painting on the easel leading our eye down and then back up into the cloaked, wizened figure of the artist holding his easel; folding stool for him to rest and other accoutrements earthing the foreground; and the massive pillars slightly askew enclosing our furtive view. Magnificent!

My favourite photograph in the posting is Garçon au coin de la place Zocodover, Tolède, 31 octobre 1898 (Boy on the corner of Zocodover Square, Toledo, October 31, 1898) (1898, below), taken when Hébert had abandoned her large format camera for a more portable Kodak. A wonderful use of depth of field, movement, vanishing point, light, architecture and the ghostly presence of a boy, forever peering at us through eons of time, lend the image an enigmatic, allegorical mystery … as to the passage of time, the journey of life.

How I wish we could have seen more of these later photographs where Hébert proposed “daring viewpoints – notably from a speeding train – a camera in motion, glances towards the camera, the operator’s shadow cast on the ground, motion blur of people and things (smoke, clouds, and waves), truncated figures, and close-ups.” (Marie Robert)

And then there is the crux of the matter. As the text on the Musée d’Orsay website insightfully observes, “… above all, photography revealed her to herself: through capturing a particularly remarkable geography and era, she effectively invented her own mythology.”

Through love and life, through devotion to husband, through devotion to photography, and through devotion to herself, she revealed her to herself and to the world. What crazy, mad love!

Dr Marcus Bunyan

PS. With photographs like Femmes à la fenêtre, Taormine (Sicile), mai 1893 (Women at the window, Taormina (Sicily), May 1893) (1893, below) it is likely Gabrielle Hébert would have met Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden (German, 1856-1931) who lived and worked there between 1878-1931.

Many thankx to the Musée d’Orsay, Paris for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Active between 1888 and 1908, Gabrielle documented daily life at Villa Medici in Rome, where her husband served as director of the French Academy. Her photographs provide an intimate look into the artistic life of the time, portraying artists, models, and domestic scenes. The exhibition features original prints, albums, diaries, glass plate negatives, and her cameras, alongside works by Ernest Hébert and personal items that tell their love story. With over 3.500 prints, Gabrielle Hébert is considered a pioneer of female photography, having sensitively and precisely documented an artistic environment predominantly male.

Veronica Azzari on the Bvlgari Hotel Paris website

When Gabriele von Uckermann and a friend discovered Ernest Hébert’s painting, La Mal’aria [below], at the Munich International Exhibition of Fine Arts in 1869, the two young women sent a telegram to the artist expressing their admiration. A few months later, the painter agreed to receive Gabriele in his Parisian studio, and their marriage in 1880 sealed their whirlwind romance. He was 63, she was 28. Five years later, Ernest Hébert’s reappointment as director of the French Academy in Rome allowed the young woman to have her own studio. Gabrielle Hébert, who had Gallicized her first name, dates her photographic debut to July 8, 1888. From that day forward, she never stopped photographing her husband. She also dedicated herself to visually documenting their stay at the Villa Medici, as well as their travels in Italy, Sicily, and Spain. …

The exhibition’s subtitle, “Mad Love at the Villa Medici,” while certainly catchy, is somewhat misleading, as the section strictly devoted to photographs related to her stay at the French Academy in Rome represents only a third of the exhibition. However, each period of this prolific output is contextualised using a variety of documents: diary entries, correspondence, camera footage, albums, contact sheets, and more.

Christine Coste. “Gabrielle Hébert, un itinéraire photographique singulier,” on the Le Journal des Arts website, 17th December, 2025 [Online] Cited 02/01/2026. Translated from the French by Google Translate. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Ernest Hébert (French, 1817-1908)

The Mal’aria

1848-1849

Oil on canvas

1930 x 1350cm

Musée d’Orsay, dist. RMN / Patrice Schmidt

Bought 1851

Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Alexis Axilette (French, 1860-1931)

Ernest et Gabrielle Hébert et leurs chiens sur la terrasse du bosco

(Ernest and Gabrielle Hébert and their dogs on the terrace of the bosco)

Around 1888

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

8.7 x 12.2cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Ernest Hébert aquarelle l’arc du balcon de la Casa Poscia, Viterbe, août 1888

(Ernest Hébert watercolour the arch of the balcony of the Casa Poscia, Viterbo, August 1888)

1888

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

9 x 12cm environ

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Le peintre pensionnaire Alexis Axilette et son modèle Elvira dans le Bosco de la Villa Médicis, Octobre 1888

(Resident painter Alexis Axilette and his model Elvira in the Bosco of the Villa Medici, October 1888)

1888

Négatif au gélatino-bromure d’argent sur plaque de verre (Silver gelatin bromide negative on glass plate)

9 x 12cm

© La Tronche, musée Hébert

Photo: Musée Hébert, Département de l’Isère

The photograph above shows a nude woman posing for the artist Alexis Axilette for his painting Summertime (c. 1891, below)

Alexis Axilette (French, 1860-1931)

Summertime

c. 1891

Only a black and white reproduction is available of this work

At the Salon exhibition of 1891, a picture which attracted a marked amount of attention was a vividly painted midsummer landscape, with the figures of three wood-nymphs, basking in the flood of golden sunshine. It was entitled “Summertime.” The painter was A. Axilette, a Parisian artist whose studio was already well known to collectors. The success of “Summertime” in Europe was enormous. It was successively exhibited at various continental exhibitions, and everywhere repeated the hit it had made in France. It was, in fact, one of those works of which it is said that they “make” their authors, and in the sense that it completely established the painter’s reputation, “Summertime” realised this figure of speech.

Mary S. Van Deusen. “Alexis Axilette,” on the Master Paintings of the World website 2007 [Online] Cited 02/01/2026. Used under fair use conditions for the purposes of education and research

Alexis Axilette (French, 1860-1931)

Alexis Axilette was born in 1860 in Durtal, a small town in Maine-et-Loire. From a modest background – his father was a merchant – his future seemed predetermined, far removed from the world of art. His parents, who dreamed of a career as a notary’s clerk for him, were nonetheless surprised to discover his talent for drawing. After encouraging him to prove his abilities, they supported his choice to become an artist, a vocation he embraced with passion and determination. This ambition led him to become one of the most remarkable painters of his time.

A Promising Start

At the age of 16, Alexis Axilette began working as an apprentice in a photography studio, retouching photographs by hand, a modern activity for the time. At the same time, he attended evening classes at the Angers Municipal School of Fine Arts, where he distinguished himself with his talent and won several prizes. Supported by his teachers, he obtained a scholarship to attend the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Between 1878 and 1880, he learned Neoclassical principles there under the influence of the renowned painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, teachings that would profoundly shape his artistic approach.

The Rise to Recognition

At 24, Alexis Axilette reached a major turning point in his career by winning the prestigious Premier Grand Prix de Rome with his painting Themistocles Taking Refuge with Admetus (1885), a masterfully executed historical scene. This success, achieved at such a young age only by Fragonard, propelled his career, marked by gold medals, honorary distinctions, and the Legion of Honor. From that moment on, he became a central figure in the artistic and literary life of the Third Republic, frequenting high society and financial circles. An accomplished artist, he traveled throughout Europe and forged an international reputation, becoming a sought-after portraitist with prestigious commissions, notably from the Imperial Court of Russia.

In 1898, he received a major state commission: the creation of a monumental triptych for the ceiling of the Social Museum, entitled Humanity, Fatherland, and Muse. This work, both moral and balanced, perfectly embodies the republican ideals of the time.

Historical and Artistic Context

Under the Third Republic, the arts were seen as a privileged means of promoting national cohesion. Axilette’s academic style, rooted in moral and patriotic values, perfectly aligned with this objective. However, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the emergence of new artistic movements such as Impressionism, Symbolism, and Expressionism. Axilette’s attachment to classicism and a rigorous aesthetic set him apart from the avant-garde movements that favored experimentation and creative freedom. Thus, although he perfectly embodied his era, his art gradually came to be perceived as outdated and obsolete.

A Transition to Pastels

In the 1910s, as artistic tastes evolved, Alexis Axilette turned to the use of pastels. This more subtle and delicate medium allowed him to explore a new sensibility while remaining true to his academic style. His works from this period, primarily portraits and landscapes, testify to his desire to renew his approach while remaining rooted in classical tradition. These pastels reveal an undiminished technical mastery and a willingness to adapt to new artistic trends, although his style seems to have been less appreciated at this time.

Posthumous Oblivion

Like many academic artists, Alexis Axilette suffered from the evolution of tastes in the 20th century. Classical art, once revered, lost ground to the avant-garde, relegating its works to museum storage. Furthermore, his image as a society artist, associated with the establishment of the Third Republic, did not help his legacy. While artists like Gauguin symbolized rebellion and innovation, Axilette remains perceived as a representative of a bygone academicism.

A body of work to be rediscovered

Alexis Axilette died on July 3, 1931, in Durtal, his birthplace. Today, his legacy lives on through his works held in private and public collections: academic drawings, nude sketches, portrait studies, landscapes, and historical paintings. These paintings bear witness to his exceptional talent and his dedication to his art. Although he was a major figure of his time, he remains relatively unknown today. He embodies the fate of many artists: celebrated in their lifetime, but gradually forgotten by history.

Anonymous. “Alexis Axilette,” on the French Wikipedia website, translated by Google Translate

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Le temps est sublime. Je photographie Lily et Farfalette, mon buste, Puech, Charpentier et Gardet, 20 novembre 1888

(The weather is sublime. I photograph Lily and Farfalette, my bust, Puech, Charpentier and Gardet, November 20, 1888)

1888

Aristotype à la gélatine, papier (Gelatin Aristotype, paper)

11 x 8cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Designed in partnership with the Musée Départemental Ernest Hébert in La Tronche (Isère), where it will be hosted in spring 2026, the exhibition will also be presented at the French Academy in Rome – Villa Medici in autumn 2026, where the exhibition’s curator Marie Robert spent a year in the context of a Villa Medici/ Musée d’Orsay cross-residency.

The exhibition Who’s Afraid of Women Photographers? (1839-1945) presented at the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie in 2015 was a milestone for recognition of women artists in France. One of the many photographers featured was Gabrielle Hébert (1853, Dresden, Germany – 1934, La Tronche, France). Born Gabrielle von Uckermann, she was an amateur painter before marrying Ernest Hébert in 1880, an academic artist twice appointed Director of the French Academy in Rome. She went on to develop an intensive, extremely prolific photography practice, begun at Villa Medici in 1888 and ending twenty years later in La Tronche (near Grenoble) following the death of the man she had idolised, her elder by almost forty years, and whose place in history she largely ensured by supporting the creation of two monographic museums.

In the late 19th century, between France and Italy, like many artists and writers (including Henri Rivière, Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis and Émile Zola) who equipped themselves with a camera to record their and their families’ daily lives, Gabrielle Hébert pursued a private, sentimental photography practice, helped along by the technical and aesthetic revolution brought about by the invention of snapshot photography. At Villa Medici, as the wife of its director, she organised receptions and received elite visitors. She was not long in escaping her assigned duties, however, and acquired a camera. She took a few lessons with a Roman professional and, along with a resident of her own age, set up a darkroom to develop and print her negatives and retouch the results. It was the beginning of an extremely voluminous output of photos, which she consigned to her diaries. Hardly a day passed without her taking a snapshot, interspersing them with remarks that tell us how she set about taking pictures: “Je photo…. Je photographie…”.

Although Gabrielle Hébert shared her taste for society portraits and tableaux vivants with Luigi and Giuseppe Primoli, Princess Mathilde Bonaparte’s nephews and pioneers of snapshot photography in Italy, she explored all photographic genres on her own at Villa Medici, including nudes, reproductions of artworks, landscapes, still lifes and “photographic recreations” … Providing us with the viewpoint of a permanent resident who is dazzled by the palace, the site and its inhabitants (artists in residence, employees, models, dogs and cats) as seen from the inside and in all seasons, her output reveals a completely unknown aspect of life in that artistic phalanstery. Her “diary in images” is the first photo-report on daily life in the institution, a centre for residencies, training and creation by winners of the Grand Prix de Rome (many of whose works are now conserved by the Musée d’Orsay) as well as a laboratory for the new political relationship between France and Italy, which had just been “unified” (1861) and of which Rome became the capital in 1871. It also constitutes a unique testimony on one of the first couples of creators at Villa Medici. Although Gabrielle assisted Ernest with his activities as an artist, posing for him, preparing his canvases, retouching his paintings and even copying them, it was Ernest himself who was the photographer’s real focus. Overturning gender stereotypes, she watched him obsessively and was never tired of capturing him on film. Posing sessions with sitters, progress made in his paintings, moments of conviviality with visitors and interactions with residents, along with walks in the Roman countryside, bathing in the sea and alone in his office: all these aspects of artist, director and husband Ernest Hébert’s life were scrutinised and documented. When she returned permanently to France with him, Gabrielle stopped cultivating her passion for photography, a passion born in Italy and in exile, but nevertheless continued to photograph Hébert until the very end of his life, determined to immortalise him through images. Before that, though, in 1898, she escaped the closed quarters formed by the Renaissance Palace and its eccentric occupants and performed her photographic swansong during a trip to Spain, which she photographed with a resolutely modern eye influenced by the early days of cinema.

This chrono-thematic exhibition, from Gabrielle Hébert’s photographic beginnings (1888) to her last images (1908), will seek to present what she made of photography and what photography made of her. Thanks to her images, which she shared and exchanged with her friends and family, she became recognised as an auteur and gained social status in a milieu where artistic creation was the preserve of men. But above all, photography revealed her to herself: through capturing a particularly remarkable geography and era, she effectively invented her own mythology. By doing so, she was Villa Medici’s first photographic chronicler and made a place for herself in the medium’s history.

Most of the works on exhibition are original prints (in 9 x 12 cm format), along with photograph albums created by Gabrielle Hébert, her diaries, boxes of glass plates and cameras she used. Enlargements created from negatives she never printed will add further life to the presentation. The itinerary will be rounded out by drawings and paintings by Ernest Hébert, as well as sentimental relics (palette, medallion and letters), testimony to a story of love for a man and a country.

Text from the Musée d’Orsay website

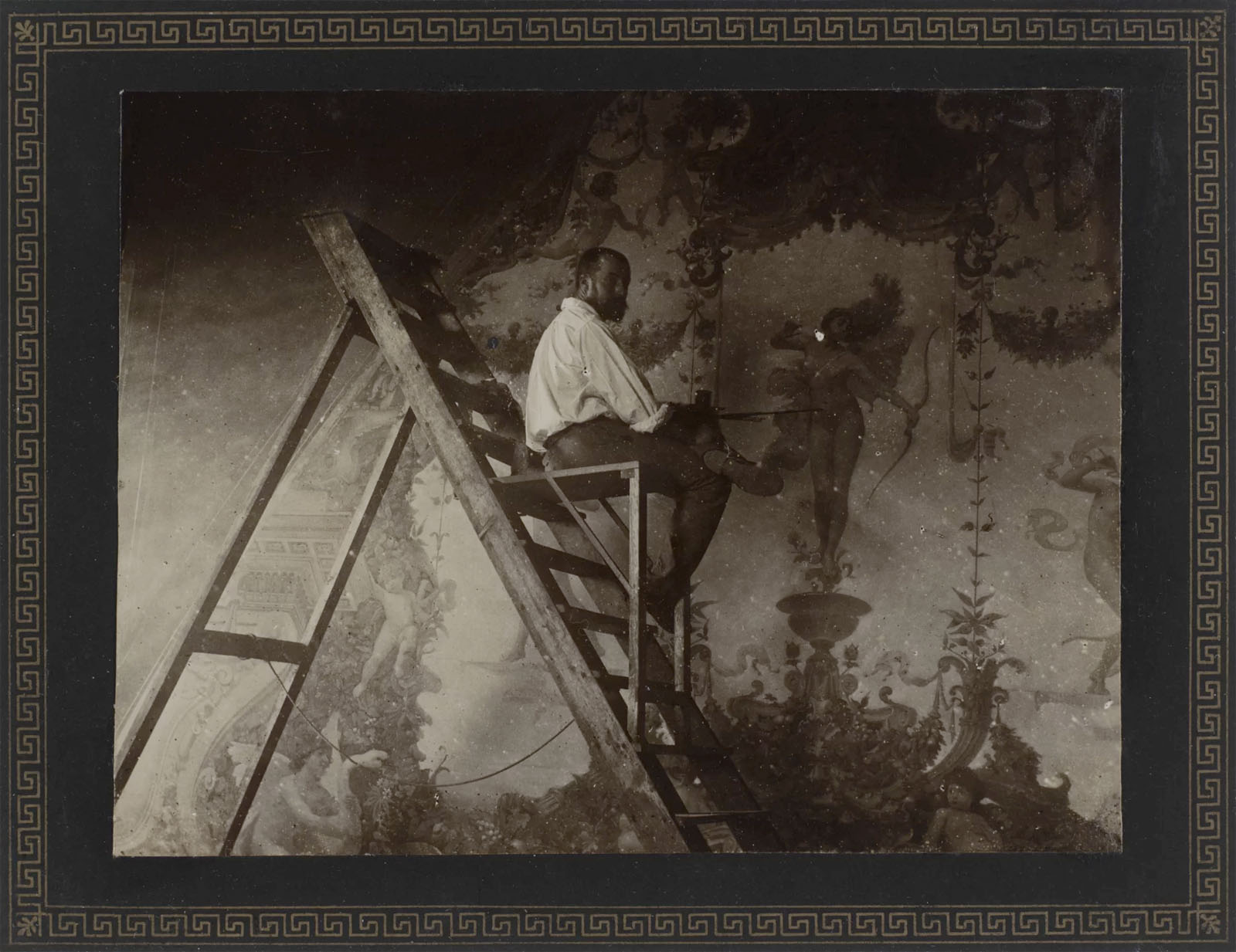

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

L’architecte Hector d’Espouy devant son Projet de plafond pour la décoration de la Villa Médicis

(The architect Hector d’Espouy in front of his ceiling design for the decoration of the Villa Medici)

1889

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

8 x 10.5cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

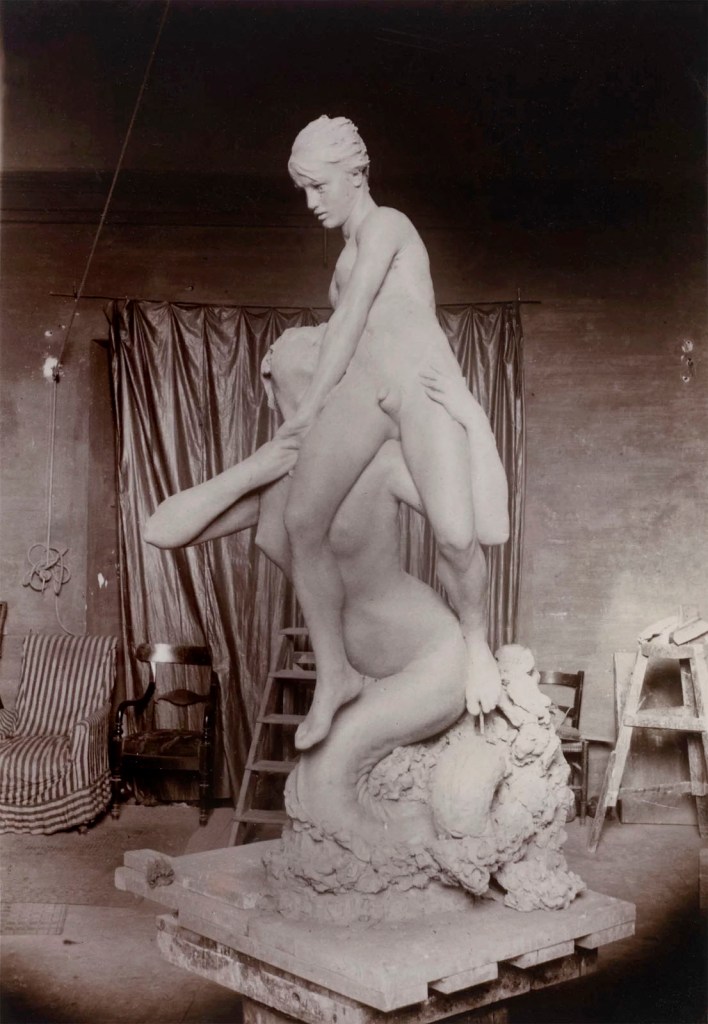

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Esquisse de La Sirène de Denys Puech dans son atelier (envoi règlementaire de quatrième année)

(Sketch of The Mermaid by Denys Puech in his studio (required submission for fourth year))

1889

Aristotype à la gélatine, papier

11.5 x 5.8cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Le jeune modèle Peppino sur l’un des lions de la loggia, 18 juin 1890

(The young model Peppino on one of the lions of the loggia, June 18, 1890)

1890

Aristotype à la gélatine, papier (Gelatin Aristotype, paper)

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

La duchesse de Mondragone et l’une de ses bellessoeurs posent pour une Annonciation, juin 1890

(The Duchess of Mondragone and one of her sisters-in-law pose for an Annunciation, June 1890)

1890

Négatif au gélatino-bromure d’argent sur plaque de verre (Silver gelatin bromide negative on glass plate)

8.4 x 11.6cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

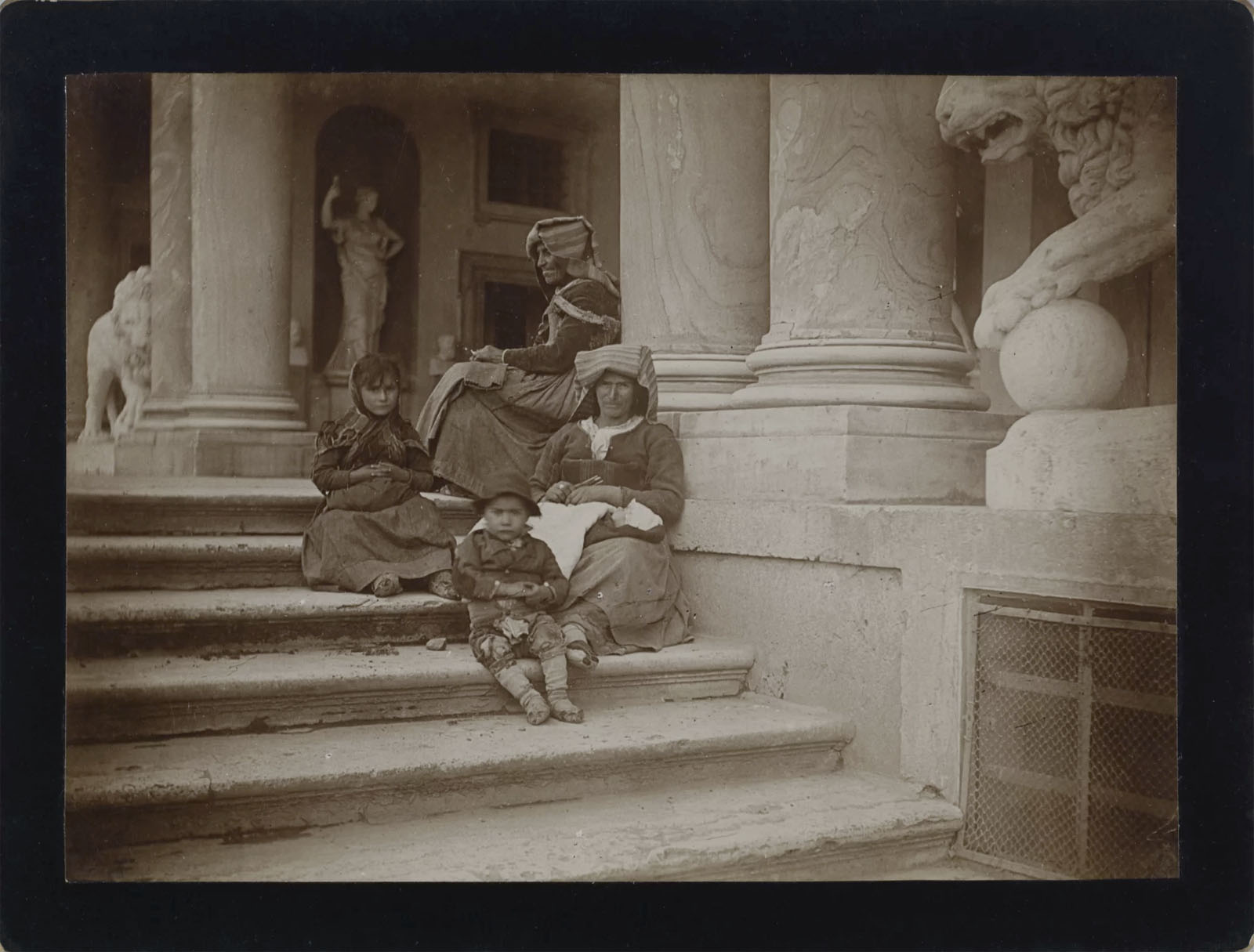

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Modèles ciociare sur les marches de la loggia (Ciociare models on the steps of the loggia)

Around 1890

Aristotype à la gélatine, contrecollé sur carton (Gelatin Aristotype, mounted on cardboard)

8.3 x 11.3cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

“Ciociaria” refers to a historic, rustic region southeast of Rome in Italy, and “ciociara” (singular) or “ciociare” (plural/feminine) describes people, especially women, from that area, known for their traditional leather sandals (ciocie), embodying a simple, rural Italian identity, famously portrayed in the film La Ciociara (Two Women). The term evokes a strong connection to the land, traditional life, and the unique culture of this central Italian territory.

Google AI

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Lys des parterres, juin 1890 (Flowerbed lilies, June 1890)

1890

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

10.5 x 12.7cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

La duchesse de Mondragone, des photographies de Gabrielle Hébert sur les genoux

(The Duchess of Mondragone, with photographs of Gabrielle Hébert on her lap)

1890

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

8.4 x 11.3cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Étude de lys dans les jardins par le pensionnaire Ernest Laurent et Ernest Hébert, en compagnie du modèle Amalia Scossa, 7 juin 1890

(Study of lilies in the gardens by boarder Ernest Laurent and Ernest Hébert, in the company of model Amalia Scossa, June 7, 1890)

1890

Aristotype à la gélatine, contrecollé sur carton (Gelatin Aristotype, mounted on cardboard)

8.1 x 11.4cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Adaptation of the texts from the exhibition in large print

Introduction

An amateur painter and wife of the artist Ernest Hébert, director of the French Academy in Rome, Gabrielle Hébert began photography intensively and passionately at the Villa Medici in 1888. She abruptly stopped twenty years later in La Tronche (near Grenoble), upon the death of the man she idolised and who was forty years her senior. She will ensure her legacy through the creation of

two monographic museums.

Like Henri Rivière, Maurice Denis, or Émile Zola, who at the end of the 19th century seized upon a camera to record family life, Gabrielle developed a private and sentimental practice, fostered by the technical and aesthetic revolution of the snapshot. As the entries “I take photos” or “I photograph” in her diary show, not a day went by without her taking pictures. Securing her place as an author through these images in a milieu where artistic creation was reserved for men, she discovered herself.

Through the chronicle of her chosen land and happy days, she creates a work of memory and inscribes herself in History.

A Woman Under the Influence

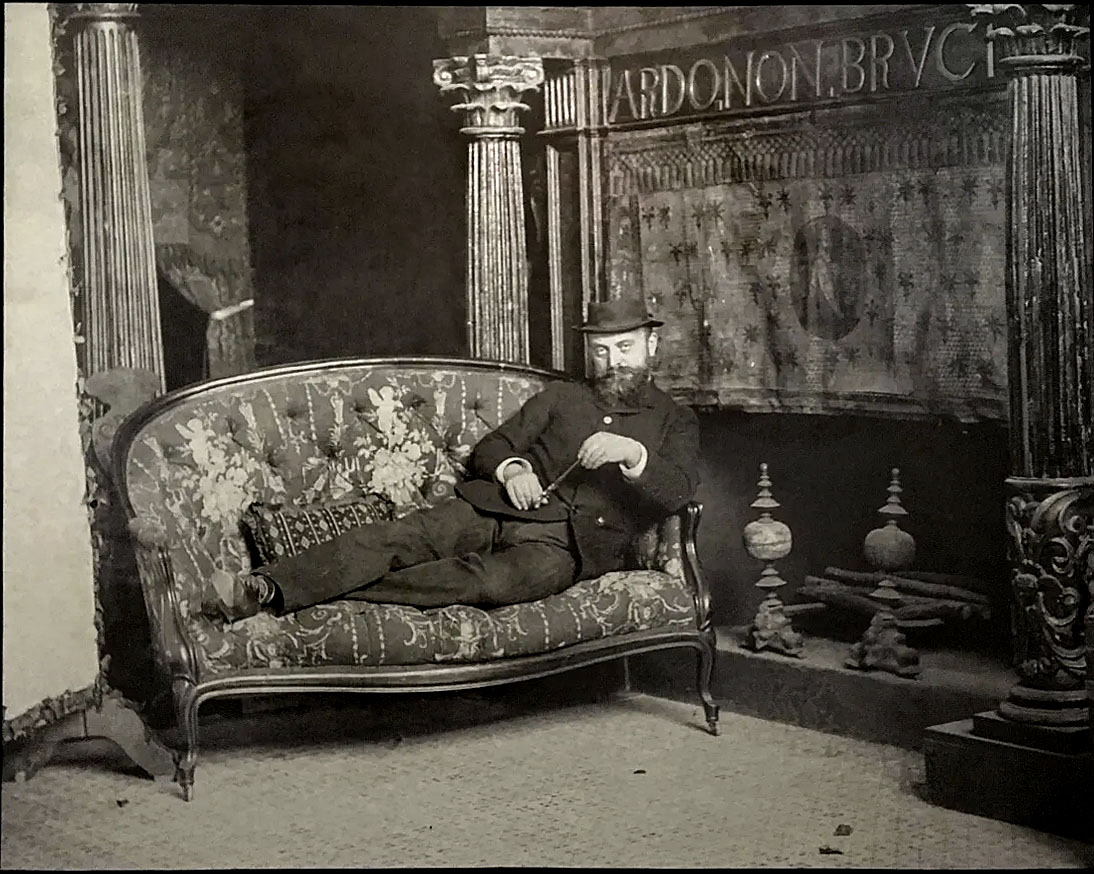

On July 21, 1888, Gabrielle “went out to buy things necessary for photography.” This marked the beginning of an obsessive production of two thousand photographs, mostly taken at the Villa Medici where, as First Lady of a prestigious cultural institution, she organised receptions and received visiting high society. Gabrielle quickly escaped the constraints of her duties: she acquired a camera, took lessons from Cesare Vasari, a Roman professional, and, together with fellow resident Alexis Axilette, set up a darkroom to develop her negatives, print, and retouch her photographs.

She already had an eye for it thanks to her artistic background and her practice of painting and drawing. But it was with the Franco-Italian counts Giuseppe and Luigi Primoli that Gabrielle explored the potential of the instantaneous, becoming the subject of a creative and existential experience: photography.

An art of joy

Gabrielle chronicles the Villa Medici, at once an architectural masterpiece overlooking the Eternal City, a residence for the winners of the Grand Prix de Rome, and a laboratory for a new relationship between France and Italy, newly unified. She focuses her gaze on its inhabitants: artists and models, foreign visitors on holiday, Italian employees at work, flowers, and animals. She enjoys working alongside the “button-pushers” in her circle, as amateurs equipped with handheld cameras are known.

She also observes professionals capturing perspectives of the palace with their imposing camera. “Magnificent weather. I’m photographing the residents”: Gabrielle often associates the day’s weather with an urgent need to act. Present in the world, joyful in her being, she then presses the shutter. Taking the picture is an epiphany. “I photograph, therefore I exist,” she seems to be saying.

Mein Alles (My Everything)

Gabrielle focuses her attention on her husband, around whom she circles and whose activities she seems to observe when he is painting or showing guests around the premises. The tender and sensitive portrait she paints of him is that of a director, an artist entirely devoted to his work at his workplaces, or sketching en plein air on excursions. She also captures him in his nakedness, as an elderly man bathing in the sea. She is concerned about his state of health; she notes how he slept or the time he got up.

The couple’s asymmetry, commonplace at that time and in that social circle, is also expressed in their writings: while he uses the informal “tu” with her, she uses the formal “vous” and addresses him with the superlative phrase “Mein Alles”: My Everything.

Travels in Italy

During their eleven-year stay in Italy, Ernest and Gabrielle travelled all over the country.

The artist enjoys returning to favorite places painted during her youth. They take with them a boarder or student, Amelia Scossa, Ernest’s beloved model, or a few friends; the dogs are always present. In 1893, they travel to Sicily, to the Duke of Aumale’s estate, and then explore the ancient sites of Selinunte and Agrigento, and the Greek theaters of Syracuse and Taormina. By escaping the confines of the Villa Medici and its eccentric inhabitants, Gabrielle literally leaves her social milieu.

With an attention full of empathy for popular and regional culture, she manages to get groups of strangers, women

and men, to pose in front of her lens, no doubt placed on a tripod, whom she brings together in an amusing jumble around a fountain or on the steps of a building, arousing in return a certain curiosity.

In Spain, a cinematic perspective

In 1896, the couple left Italy with great regret and sorrow, returning to Paris and La Tronche where they continued to lead an intense social life. Two years later, Gabrielle completed her photographic swan song during a final journey, this time to Spain, which took them both from Burgos to Granada via Madrid, El Escorial, Toledo, Granada, and Seville.

Abandoning her large-format camera for a Kodak, she amplified in nearly three hundred photographs what she had already experimented with: daring viewpoints – notably from a speeding train – a camera in motion, glances towards the camera, the operator’s shadow cast on the ground, motion blur of people and things (smoke, clouds, and waves), truncated figures, and close-ups.

The nascent cinematograph had passed by. She no longer poses her subjects; she captures them on the fly. She seizes fleeting gestures, radiant moments, the stroll of passersby, the burst of laughter. This journey is an enchanted interlude that allows the couple to get back on their feet, one last time.

The tomb of an artist

Upon returning from Spain, Gabrielle ceased to cultivate her passion, born under the Italian sky. Her output diminished significantly, ceasing altogether in 1908, with Ernest’s death.

During his final months, she recorded his last visits and outings in the sun, his walks, and setting up his easel outdoors. She portrayed him as a draftsman and painter to the very end, then staged his posthumous portrait, for eternity. Containing the seeds of anticipation of the end, the photographs of moments lived, places visited, and people met, were in reality intended to be viewed by others besides their sole author.

With her thousands of images, Gabrielle composed a tomb, in the poetic sense of the word, erected in memory of her husband and their love. In the museum she created in Isère, in La Tronche, in honour of Ernest, it would take until the beginning of the 21st century for her photographic work to be discovered by a happy accident.

Marie Robert, Chief Curator, Photography and Cinema at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, translated from the French by Google Translate

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Arrière de la statue d’Apollon vainqueur du monstre Python, 13 mai 1891

(Back of the statue of Apollo victorious over the Python monster, May 13, 1891)

1891

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

8.2 x 10.9cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

La façade du palais sous la neige, 16 janvier 1891 (The palace façade under the snow, January 16, 1891)

1891

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

8.2 x 11.2cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Éléonore d’Uckermann, le modèle Natalina, le prince Abamelek-Lazarev et le chien Farfaletta sur la terrasse du bosco, 5 janvier 1891

(Eleanor d’Uckermann, the model Natalina, Prince Abamelek-Lazarev and the dog Farfaletta on the terrace of the bosco, January 5, 1891)

1891

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

8 x 10.8cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Prince Semyon Semyonovich Abamelek-Lazarev (also Abamelik-Lazaryan; Russian: Семён Семёнович Абамелек-Лазарев; 24 November 1857 in Moscow – 2 October 1916 in Kislovodsk) was a Russian millionaire of Armenian ethnicity noted for his contributions to archaeology and geology.

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Amalia Scossa et Ernest Hébert à sa peinture La Vierge au chardonneret sur la terrasse du campanile

(Amalia Scossa and Ernest Hébert at his painting The Virgin with the Goldfinch on the bell tower terrace)

Around 1891

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

9.6 x 12.3cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

The painting in the photograph is probably La Vierge de Chausseur by Ernest Hébert (c. 1891, below)

Ernest Hébert (French, 1817-1908)

La Vierge de Chausseur

c. 1891

Oil on canvas

73cm (28.7 in); width: 47cm (18.5 in)

Public domain

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Sarah Bernhardt dans le studio aménagé de Giuseppe Primoli, Rome, février 1893

(Sarah Bernhardt in Giuseppe Primoli’s furnished studio, Rome, February 1893)

1893

Négatif sur plaque de verre au gélatinobromure d’argent (Gelatin silver bromide glass plate negative)

9 x 12cm

© La Tronche, musée Hébert

Photo: Musée Hébert, Département de l’Isère

Giuseppe Primoli (Italian, 1851-1927)

Count Giuseppe Napoleone Primoli (in French, Joseph Napoléon Primoli; 2 May 1851 in Rome – 13 June 1927 in Rome) was an Italian nobleman, collector and photographer. …

Giuseppe Primoli lived in Paris from 1853 to 1870. He befriended writers and artists both in Italy and France, and was host to Guy de Maupassant, Paul Bourget, Alexandre Dumas fils, Sarah Bernhardt and others in Palazzo Primoli in Rome. In 1901 he became the sole owner of the palazzo, which he enlarged and modernised between 1904 and 1911.

Primoli was a bibliophile and collector, who assembled a large collection of books and prints. He amassed a collection of books by Stendhal as well as many from the writer’s library.

During the last decades of the nineteenth century, Primoli, an avid photographer, produced over 10,000 photographs.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Anonymous photographer

Giuseppe Primoli in his palace in Rome

c. 1911-1912

Primoli Foundation, Rome

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Femmes à la fenêtre, Taormine (Sicile), mai 1893 (Women at the window, Taormina (Sicily), May 1893)

1893

Aristotype à la gélatine, papier (Gelatin Aristotype, paper)

7.8 x 11.4cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

With photographs like the one above, taken at Taormina, it is likely Gabrielle Hébert would have met Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden (German, 1856-1931) who lived and worked there between 1878-1931.

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Paysans avec leurs chèvres, Sicile, mai 1893 (Peasants with their goats, Sicily, May 1893)

1893

Aristotype à la gélatine, papier (Gelatin Aristotype, paper)

7.9 x 10.9cm

La Tronche, Musée Hebert

© Musée Hébert, Département de l’Isère

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Procession sur le port de Brindisi (Pouilles) (Procession in the port of Brindisi (Apulia))

1893

Aristotype à la gélatine, papier (Gelatin Aristotype, paper)

8.0 x 11.4cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Garçon au coin de la place Zocodover, Tolède, 31 octobre 1898

(Boy on the corner of Zocodover Square, Toledo, October 31, 1898)

1898

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

10 x 10cm

La Tronche, musée Hebert

© Musée Hébert, Département de l’Isère

Gabrielle Hébert (French born Germany, 1853-1934)

Ernest Hébert sur son lit de mort, novembre 1908 (Ernest Hébert on his deathbed, November 1908)

1908

Aristotype à la gélatine (Gelatin Aristotype)

9.5 x 9.8cm

© Musée National Ernest Hébert, Paris

Photo: Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

Musée d’Orsay

62, rue de Lille

75343 Paris Cedex 07

France

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 9.30am – 5pm

Closed on Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.