Exhibition dates: 29th March – 4th August 2024

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Dora Maar

1936

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Henriette Theodora Markovitch (22 November 1907 – 16 July 1997), known as Dora Maar, was a French photographer, painter, and poet. Maar is very well known for her role as Picasso’s lover, subject, and muse. He abused her. Maar photographed the successive stages of the creation of Guernica. It is the gelatin silver works of the surrealist period that remain the most sought after by admirers: Portrait of Ubu (1936), 29 rue d’Astorg, black and white, collages, photomontages or superimpositions.

Man Ray is hailed as one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century, but I admit I have no real liking for most of his work.

I remember seeing the first large-scale exhibition of Man Ray’s photography to have been presented in Australia at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2004. In text about the exhibition the NGV states, “Man Ray produced some of the most iconic photographs of the 20th century: eloquent portraits, dreamy solarised nudes, divine fashion photography and enigmatic images that continue to delight and astonish… A superb technician and a highly inventive artist, Man Ray always denied that he had any ability with the camera or in the darkroom. However, as the exhibition reveals, this is clearly not the case. The exhibition emphasises Man Ray’s techniques of framing, cropping, solarising and use of the photogram to present a new ‘surreal’ way of seeing, which continues to fascinate audiences today.”1

I came away from that exhibition thinking what a great technician Man Ray was, almost like a photographic scientist, an alchemist from another world conjuring small, intense images of clinical focus, but where was the emotional power of the images, where was their … what am I trying to enunciate … where was their vibrational energy. They were ice cold.2

I feel that Man Ray’s greatest artistic expression, his greatest music, were his photograms, “which he coined “rayographs” after himself. He explained that working with light in the darkroom allowed him to free himself from painting.” (Press release) As Man Ray himself said of his rayographs, “Like the undisturbed ashes of an object consumed by flames these images are oxidised residues fixed by light and chemical elements of an experience, an adventure, not an experiment. They are the result of curiosity, inspiration, and these words do not pretend to convey any information.”3

“What the rayographs do not deny, however, is the subjectivity of the artist, his skill at placing the objects on the photographic paper, expressed in their dream-like nature, both a subjective ephemerality (because they could only be produced once) and an ephemeral subjectivity (because they were expressions of Man Ray’s fantasies, and therefore had little substance). Through an alchemical process the latent images emerge from the photographic paper, representations of Man Ray’s fantasies as embodied in the ‘presence’ of the objects themselves, in the surface of the paper.”4

(See a section of my paper “The Delicious Fields: Exploring Man Ray’s Rayographs in a Digital Future” (2004) below in the posting).

On a final note, while it is fantastic to see such a large group of Man Ray’s photographs together in one space I am amazed, flabbergasted even, at the blue and yellow colour scheme on the floor of the gallery. What were they thinking? How can you appreciate black and white images, which are never actually black and white but always have subtle colours of either brown and blue, warm and cool, which need to be appreciated in a neutral colour space … when throughout the gallery your eye is constantly overwhelmed (by reflection from the gallery lights or subconsciously, even) by a sea of blue and yellow tiles. It makes no sense aesthetically, empirically or emotionally.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Anonymous. “Man Ray,” on the National Gallery of Victoria website Nd [Online] Cited 18/07/2024

2/ This coldness can be seen in the photographs from the book at the bottom of the posting, where borders frame faces and are inverted, where objects in rayographs are paired opposite objective portraits, surface representations a human visage.

3/ Man Ray quoted in Janus (trans. Murtha Baca). Man Ray: The Photographic Image (London: Gordon Fraser, 1980), 213 quoted in Marcus Bunyan. “The Delicious Fields: Exploring Man Ray’s Rayographs in a Digital Future,” published in The University of Queensland Vanguard Magazine: ‘Man Ray: Life, Work and Themes’, 2004, Triad series #2, pp. 40-46. ISBN 0-9756043-0-9

4/ Bunyan, op cit.,

Many thankx to the Photo Elysee for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“There is no eggshell, no thermometer or metronome, no brick, bread or broom that [Man Ray] cannot and does not change into something else. It is as if he discovers the soul of each conventional object by liberating it from its practical function…. [Man Ray] just cannot help to discover and reveal things because his whole person is involved in a process of continuous probing, of a natural distrust in things being “just so”.”

Hans Richter 1966

Installation views of the exhibition Man Ray. Liberating Photography at the Photo Elysee, Lausanne, showing in the bottom image at right, Man Ray’s Nude, Kiki de Montparnasse 1927; Artichokes in Bloom 1934; and Still life Plaster Venus with Fruit c. 1936

© Khashayar Javanmardi and Photo Elyse Plateforme

“To be totally liberated from painting and its aesthetic implications” was the first avowed aim of Man Ray (United States, 1890-1976), who began his career as a painter. Photography was one of the major breakthroughs of modern art and led to a rethinking of notions of representation. In the 1920s and 30s, the photographic medium came to the forefront of the avant-garde movement, and Man Ray soon made a name for himself with his virtuosity. As a studio portraitist and fashion photographer, but also as an experimental artist who explored the potential of photography with the people around him, Man Ray was a multi-faceted figure. Considered one of the 20th century’s major artists, close to Dada and then Surrealism, he photographed Paris’ artistic milieu between the wars.

Exhibition

Curated from a private collection, the exhibition explores the artist’s extensive social contacts while presenting some of his most iconic works. In addition to providing a dazzling who’s who of the Parisian avant-garde, the works also highlight the innovations in photography made by Man Ray in Paris in the 1920s and 30s.

Artist

He took his first photographs in New York in the 1910s, but it was in Paris that his career took off. Even before opening his studio in Montparnasse in 1922, Man Ray worked for a year in his hotel room. The photographer’s reputation grew, and before long, the artist’s studio was flourishing. Fashion photographs alternated with portraits of the artistic figures of the day who had made Paris’ notoriety: Marcel Duchamp, whom he met in New York in 1915 and who introduced him to the Parisian artistic elite, as well as Robert Delaunay, Georges Braque, Alberto Giacometti and Pablo Picasso, among others, who posed for the photographer. His portraits also included Ballets Russes dancers and guests at the Count de Beaumont’s ball.

As soon as he arrived in Paris in the summer of 1921, Man Ray immediately became part of the Parisian intelligentsia of the Roaring Twenties. He met Jean Cocteau, who was himself a fixture of the Parisian art scene, André Breton, Francis Picabia, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, Henri Matisse and Max Ernst. He also met Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, Igor Stravinsky, Ernest Hemingway, Arnold Schoenberg and James Joyce, whom he photographed for the Anglo-American bookshop Shakespeare and Company. But Man Ray was not merely content to have celebrities pose in his studio or to explore the female nude genre by working with those he considered his muses, such as Lee Miller, Kiki de Montparnasse, Meret Oppenheim and Adrienne Fidelin.

Creative Process

Man Ray also experimented in the darkroom, transforming the photographic medium into a powerful tool of artistic expression, even going so far as to do away with the camera when, in 1921-1922, he began creating photograms, which he coined “rayographs” after himself. He explained that working with light in the darkroom allowed him to free himself from painting, so convinced was he of the visual power of his experiments. Also in the 1920s, he experimented with the moving image and produced four films. The rhythm and freedom offered by the cinema complemented his photographic work, in which he saw a close relationship between film and poetry. This is why he gave his film Emak Bakia (1926) the subheading of “cinépoème”. Without ever abandoning portraiture, he experimented with other techniques in the 1930s: solarisation, overprinting and other distortions.

From the outset, photography has been more than a simple process of reproduction. For him, images were not taken fleetingly, but meticulously realised indoors. Unlike Henri Cartier-Bresson who opted for the spontaneous gesture and saw the street as a privileged playground, Man Ray composed and staged his photographs. The studio provided him with a space in which to explore his imagination. Some of the themes dear to the Surrealists can be found in his work: femininity, sexuality, strangeness, the boundary between dream and reality. His nude studies were part of his artistic research, which he developed in close collaboration with his companions who were part of the Parisian art scene. Kiki de Montparnasse – the woman with the f-holes of a violin on her back – whose real name was Alice Prin, was a dancer, singer, actress and painter who posed for artists such as Chaïm Soutine and Kees van Dongen. Lee Miller, a fellow New Yorker like him, had begun a modelling career in the United States but wanted to move to the other side of the camera. She met the photographer in Paris in 1929 when she was 22-years old, and became active in the Surrealist movement. More than a muse, she became his collaborator, learning photography at his side. Together, they discovered the technique of solarisation. Another artist with whom Man Ray had a professional and romantic relationship was the Swiss artist Meret Oppenheim, who was close to the Surrealist scene before pursuing an independent career as an artist.

Man Ray loved the freedom his photographic creations afforded him, and portraits and fashion photography enabled him to earn a living. It was in his studio that he embarked on a series of visual experiments. His portraits, which are relatively classical in style, testify not only to his commercial success, but also to his great sociability. Artists from Montparnasse, Surrealists, fashion and nightlife celebrities, patrons of the arts, Americans in Paris – the entire artistic elite – passed through his studio, as was the case with Nadar in the 19th century. Almost 50 years after Man Ray’s death, his photographs continue to fascinate us. His impact on the history of the medium is undeniable, and he served as an inspiration to photographers of the caliber of Berenice Abbott, Bill Brandt and Lee Miller. Man Ray remains one of the most famous photographers of the 20th century. He never stopped creating, without prejudice or constraint.

Press release from the Photo Elysee

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Black and White

1926

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Larmes (Tears)

1930

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Head, New York

1920

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Alice Prin, known as Kiki de Montparnasse

Around 1925

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Nancy Cunard

c. 1925

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Jacqueline Goddard

c. 1932

Solarised gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Paul Eluard and André Breton

1939

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Few names in the history of photography are as illustrious at that of Man Ray, born Emmanuel Radnitzsky (1890-1976) in the United States. Studio portraitist, fashion photographer and experimental artist, he explored the many potentialities of photography at a time when the medium was asserting itself as the very expression of modernity. Mingling with the Paris art scene of the early 20th century, and a close friend of Marcel Duchamp and André Breton, he was one of the few photographers to be mentioned among the Dada artists and Surrealists.

When Man Ray decided to become a professional photographer, it was primarily because he saw it as a way to earn a living. His studio rapidly became a gathering place for the entire Parisian art scene of its day: Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Robert Delaunay, Alberto Giacometti, Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst, among others. His work includes portraits of the artists, writers and intellectuals in his circle, including Coco Chanel, Paul Éluard, James Joyce, Elsa Schiaparelli, Igor Stravinsky and Virginia Woolf. Not just content to have celebrities pose in his studio, he tried his hand at staging and photographing his female models – Lee Miller, Kiki de Montparnasse and Meret Oppenheim – in a variety of different settings. Following his encounter with the famous fashion designer Paul Poiret, Man Ray also worked as a fashion photographer for French and American Vogue, as well as for Harper’s Bazaar.

Man Ray, whose career spanned more than 60 years, saw the medium as a creative tool that would allow him to go beyond the representation of reality. While always exploring abstraction, he also made relatively traditional portraits of the artists who surrounded him – a circle to which he was introduced by Marcel Duchamp just after he arrived in Paris. He is the creator of Violon d’Ingres [Ingres’s Violin] – the iconic photograph taken in 1924 that can be found in every art history book published in the 20th century. Man Ray remains an important name in the worlds of art, fashion and pop culture, with so many artists referring to the photographs of this iconic figure of modern art.

Curated from a private collection, the exhibition explores the artist’s extensive social contacts while presenting some of his most iconic works.

1. PROOF AND PRINT, A QUESTION OF VOCABULARY

The question of Man Ray’s prints has remained a source of fascination throughout the history of photography. His work went through a series of successive generations of prints over the course of the 20th century, starting with prints made shortly after the photograph was taken: contact prints and more refined prints that highlight his artistic choices. From the 1950s onwards, Man Ray reinterpreted certain photographs to produce new prints, sometimes changing the framing. He also enlisted the services of various photographic laboratories such as Picto, and, in particular, the renowned printer Pierre Gassman, whose lab produced many posthumous prints.

The prolific nature of Man Ray’s work is reflected by some 12,000 negatives from his studio archive that were added to the collections of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The experimental and pioneering nature of Man Ray’s work raises a number of particular questions, especially in relation to the photograms that he produced and reproduced, contradicting their primary characteristics as unique works. All these elements make it more difficult to determine the artist’s intention as well as the aesthetic and historical value of his works, compared to other, more linear authors. The way we refer to Man Ray’s photographs is therefore important, and the notions of proof, print and original are paramount.

Proof

A term from the world of printmaking and sculpture, it was adopted at the birth of photography by François Arago in his 1839 lecture. It designates the object obtained from a matrix, in photography, from a negative.

Original proof

Any copy made under the control of the artist or the holders of his or her moral rights and whose history can be traced. In the absence of this relationship, the object is considered a reproduction and not an original work.

Contact print

A print obtained by placing the negative directly on photosensitive paper. It is generally for the photographer’s use only and is used as a reference for an archiving system and as a tool to read newly printed photographs for the first time. A distinction must be made between contact prints, which are the same size as the negative and on which Man Ray generally cropped his photographs, and contact sheets, which allow the viewer to see the entire photographic film.

Vintage print

A print made during the period when the photograph was taken, and whose formal characteristics (format, tonality, contrast, inscriptions) reflect the artist’s intention. Sometimes, authors – as in the case of Man Ray – revisit their archives and produce new prints from an old negative, years after it was produced. This is known as a late print, or even a posthumous print when made by the artist’s beneficiaries after his or her death. All the posthumous prints in this exhibition are by Pierre Gassman.

Countertype

Countertype is obtained by re-photographing a photographic image. Man Ray often countertyped his original photograms for distribution and even sale.

2. STUDIO

‘To be totally liberated from painting and its aesthetic implications’ was the first avowed aim of Man Ray, who began his career as a painter.

Photography was one of the major breakthroughs of modern art and led to a rethinking of representation. In the 1920s and 30s, the photographic medium came to the forefront of the avant-garde movement, and Man Ray soon made a name for himself with his virtuosity. His photographs were not taken fleetingly, but rather meticulously produced in the studio. Unlike some photographers who see the street as a privileged playground, Man Ray composed and staged his photographs. The studio provided him with a space in which to explore his imagination.

3. ELITE

From the moment he arrived in Paris in the summer of 1921, Man Ray was part of the Parisian intelligentsia of the Roaring Twenties. Even before opening his studio in Montparnasse in 1922, he worked from his hotel room. His reputation as a photographer grew rapidly. He photographed Marcel Duchamp, whom he had met in New York in 1915, and who introduced him to the Parisian artistic elite and to many other painters such as Robert Delaunay, Georges Braque, Alberto Giacometti and Pablo Picasso. He met Jean Cocteau, who was himself a fixture of the Parisian art scene, as well as André Breton, Francis Picabia, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, Henri Matisse and Max Ernst, plus many intellectual figures of his day, including Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, Igor Stravinsky, Ernest Hemingway, Arnold Schönberg and James Joyce.

4. MUSES

Through photography, a medium with multiple possibilities, the Surrealists sought not to reproduce reality, but to sublimate it. Love, as seen primarily by men, was an example of this idea of transformation. An essential notion for Luis Buñuel and Paul Éluard, love was a means of escaping reality and evoking the extraordinary. Femininity, sexuality and the fine line between dream and reality were dominant themes in Man Ray’s work when he was exploring the female nude, having those he considered to be his muses pose for his camera. He photographed Lee Miller, a fellow New Yorker who had begun a career as a model but wanted to move to the other side of the camera; Alice Prin, known as Kiki de Montparnasse, the woman with the fholes of a violin on her back, dancer, singer, actress and painter; and the Swiss artist Meret Oppenheim, who was close to the Surrealist scene before pursuing an independent career as an artist, and with whom he also had a professional and romantic relationship. In the late 1930s, Man Ray had his partner, Adrienne Fidelin, known as Ady, a dancer from Guadeloupe, pose for him.

5. EXPERIMENTATIONS

Man Ray also experimented in the darkroom, transforming the photographic medium into a powerful tool of artistic expression, even going so far as to do away with the camera when, in 1921-1922, he began creating photograms, which he coined ‘rayographs’ after himself. He described this darkroom work as a way of freeing himself from painting, so convinced was he of the visual power of his experiments. By placing objects directly onto photosensitive paper, he could play with shadows and light, fascinated by the abstractions created by this technique and that produced a unique work of art. He experimented with other techniques in the 1930s: solarisation, double exposures and different forms of distortion.

6. CINEMA

For the Surrealists, cinema, an art form that had emerged 20 years earlier, represented a means of transcending reality. Silent, dreamlike and highly suggestive, it resisted interpretation. In the 1920s, Man Ray tried his hand at the moving image, making four films. The rhythm and freedom offered by cinema complemented his photographic production, in which he saw a close relationship between film and poetry. For this reason, he gave his film Emak Bakia (1926) the subheading of ‘cinépoème’.

Texts: Nathalie Herschdorfer, Sarah Bourget and Wendy A. Grossman

English translation: Gail Wagman

Proofreading: Hannah Pröbsting

Exhibition texts from the Photo Elysee

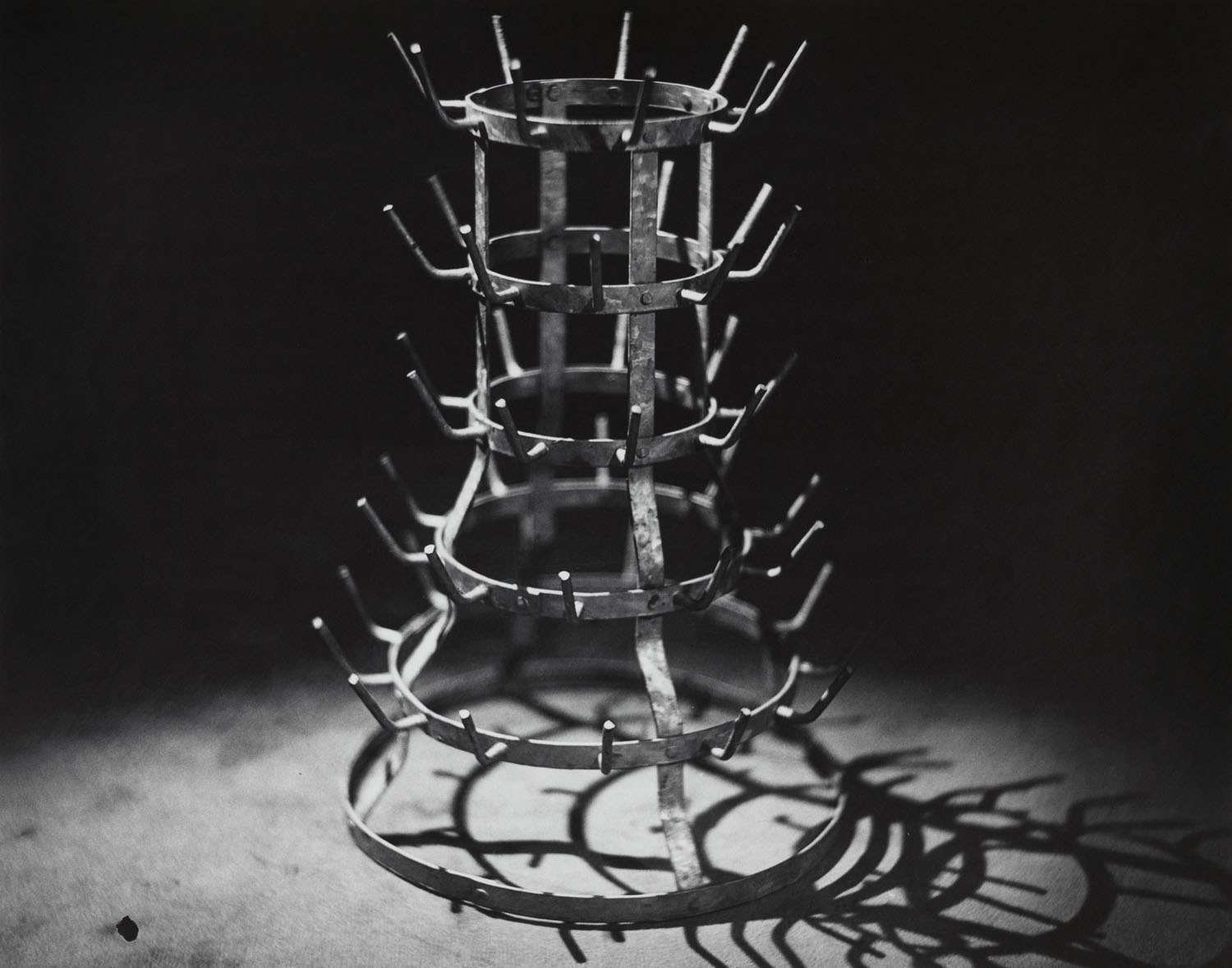

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Bottle-holder by Marcel Duchamp

c. 1920

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Flowers

1925

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

In my early paper titled “The Delicious Fields: Exploring Man Ray’s ‘Rayographs’ in a Digital Future” published in The University of Queensland Vanguard magazine special edition ‘Man Ray: Life, Work & Themes’ (2004) I wrote:

The rayographs

After his arrival in Paris Man Ray started experimenting in his darkroom and discovered the technique for his rayographs by accident. With the help of his friend the Surrealist poet Tristan Tzara, he published a portfolio of twelve rayographs in 1922 called ‘Les champs délicieux’ (The delicious fields). “This title is a reference to ‘Les champs magnétiques’, a collection of writings by André Breton and Philippe Soupault composed from purportedly random thought fragments recorded by the two authors.”1 The rayographs are visual representations of random thought fragments, “photographic equivalents for the Surrealist sensibility that glorified randomness and disjunction.”2 Man Ray, “denied the camera its simplest joy: the ability to capture everything, all the distant details, all the ephemeral lights and shadows of the world”3 but, paradoxically, the rayographs are the most ephemeral of creatures, only being able to be created once, the result not being known until after the photographic paper has been developed. In fact, for Man Ray to create his portfolio ‘Les champs délicieux’ (The delicious fields), he had to rephotograph the rayographs in order to make multiple copies.4

Man Ray “insisted in nearly every interview that the rayograph was not a photogram in the traditional sense. He did something that a photogram didn’t; he introduced depth into the images,”5 which denied the images their photographic objectivity by depicting an internal landscape rather than an external one.6 What the rayographs do not deny, however, is the subjectivity of the artist, his skill at placing the objects on the photographic paper, expressed in their dream-like nature, both a subjective ephemerality (because they could only be produced once) and an ephemeral subjectivity (because they were expressions of Man Ray’s fantasies, and therefore had little substance). Through an alchemical process the latent images emerge from the photographic paper, representations of Man Ray’s fantasies as embodied in the ‘presence’ of the objects themselves, in the surface of the paper. …

Finally, within their depth of field the rayographs can be seen as both dangerous and delicious, for somehow they are both beautiful and unsettling at one and the same time. As Surrealism revels in randomness and chance these images enact the titles of other Man Ray photographs: ‘Danger-Dancer’, ‘Anxiety’, ‘Dust Raising’, ‘Distorted House’. The rayographs revel in chance and risk; Man Ray brings his fantasies to the surface, an interior landscape represented externally that can be (re)produced only once – those dangerous delicious fields.7

Marcus Bunyan. “The Delicious Fields: Exploring Man Ray’s Rayographs in a Digital Future,” in The University of Queensland Vanguard Magazine: ‘Man Ray: Life, Work and Themes’, 2004, Triad series #2, pp. 40-46. ISBN 0-9756043-0-9

Footnotes

1/ Greenberg, Mark (ed.,). In Focus: Man Ray: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1998, p. 28 quoted in Bunyan, op cit.,

2/ Perl, Jed (ed.,). Man Ray: Aperture Masters of Photography. New York: Aperture, 1997, pp. 11-12 quoted in Bunyan, op cit.,

3/ Ibid., pp. 5-6 quoted in Bunyan, op cit.,

4/ Greenberg, Mark (ed.,). In Focus: Man Ray: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1998, p. 28 quoted in Bunyan, op cit.,

5/ Ibid., p. 112 quoted in Bunyan, op cit.,

6/ Ibid., p. 28 quoted in Bunyan, op cit.,

7/ Marcus Bunyan. “The Delicious Fields: Exploring Man Ray’s Rayographs in a Digital Future,” in The University of Queensland Vanguard Magazine: ‘Man Ray: Life, Work and Themes’, 2004, Triad series #2, pp. 40-46. ISBN 0-9756043-0-9

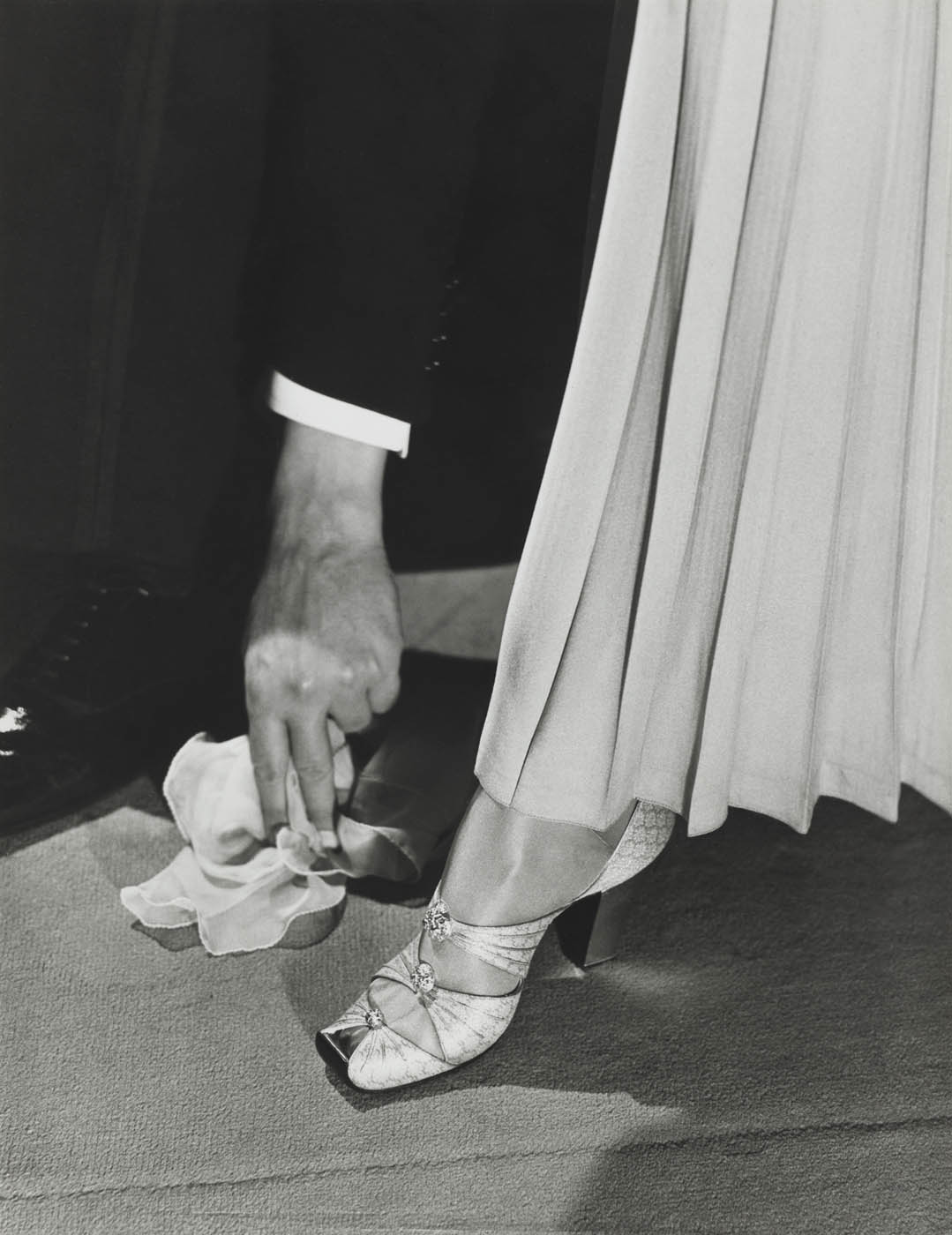

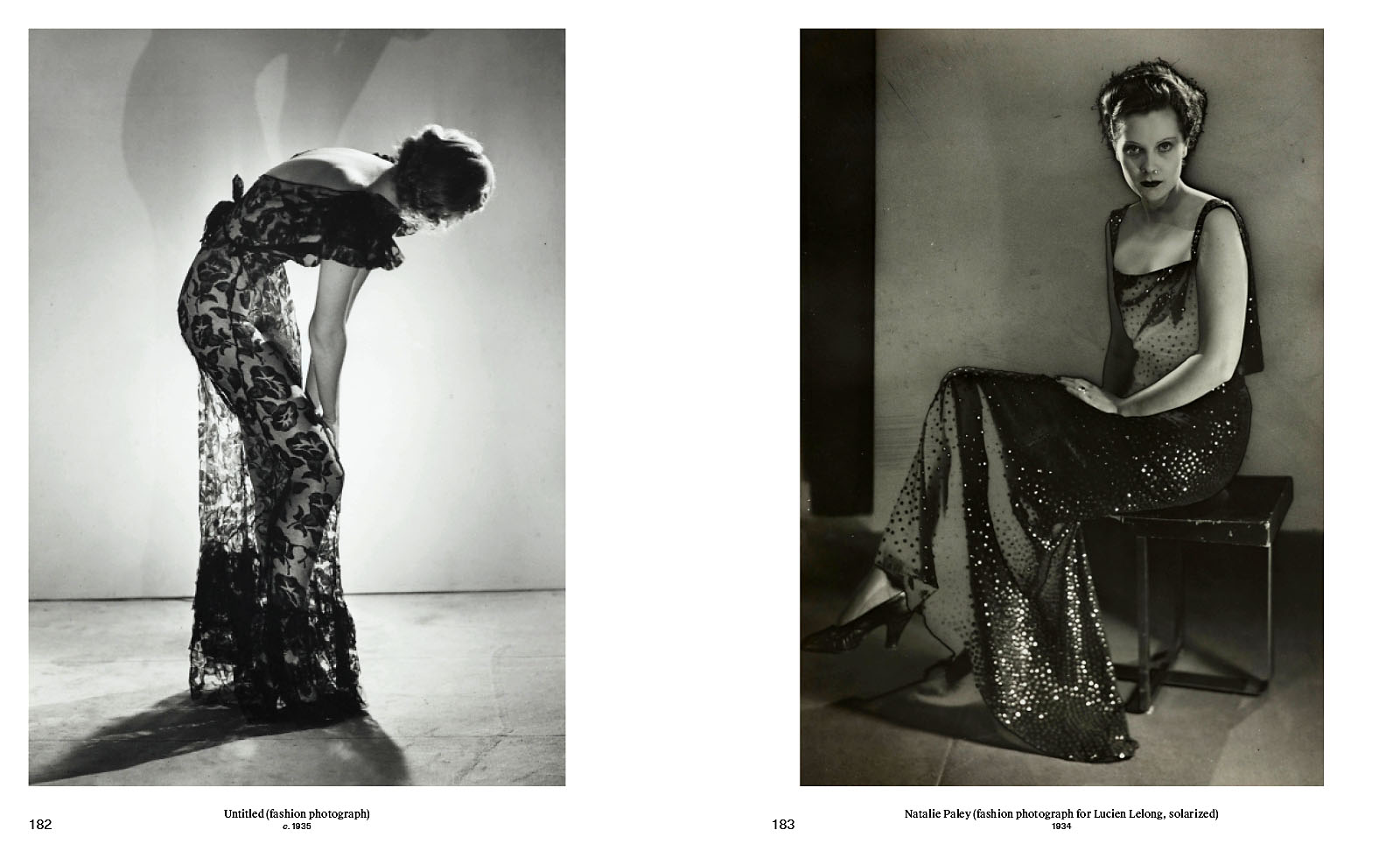

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Fashion photograph

c. 1935

Gelatin silver print

© Man Ray 2015 Trust / 2024, ProLitteris, Zurich. All rights reserved

Without permission from ProLitteris, the reproduction or any use of the individual and private consultation are prohibited

Man Ray. Liberating Photography book cover

Man Ray. Liberating Photography

Nathalie Herschdorfer, Wendy Grossman

Published in connection with an exhibition opening at Photo Elysée in spring 2024, this book presents more than one hundred and fifty of Man Ray’s portraits, primarily from the 1920s and ’30s.

Man Ray (1890-1976) was a man both of and ahead of his time. With his conceptual approach and innovative techniques, he liberated photography from previous constraints and opened the floodgates to new ways of thinking about the medium.

A close friend of Marcel Duchamp and André Breton, he was one of the few photographers to be mentioned among the Dada artists and surrealists. He also worked as a fashion photographer, first for Vogue and later for Harper’s Bazaar and Vanity Fair. Renowned as the creator of Ingres’s Violin – a photograph from 1924 that broke records when it was sold for $12.4 million in 2022 – Man Ray remains an influential figure in the worlds of art, fashion, and pop culture, with many other artists referencing his work.

Published in connection with an exhibition at Photo Elysée and in the centennial year of the publication of André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto, Man Ray presents more than one hundred and fifty of Man Ray’s portraits, primarily from the 1920s and ’30s. It includes portraits of the leading lights of the Paris art scene, among them Marcel Duchamp, Robert Delaunay, Georges Braque, Alberto Giacometti, and Pablo Picasso, as well as a selection of his fashion work. As an innovator of photographic techniques and compositional form, Man Ray found the studio portrait – be it of the artists and writers with whom he had longstanding friendships or of the objects and sculptures he collected – to be the playground in which he could express the visual wit and experimentation for which he is renowned.

Format: Hardcover

Pages: 224

Artwork: 153 black-and-white illustrations

Size: 7.75 in x 9.5 in

Forthcoming: September 10th, 2024

ISBN-10: 0500028117

ISBN-13: 9780500028117

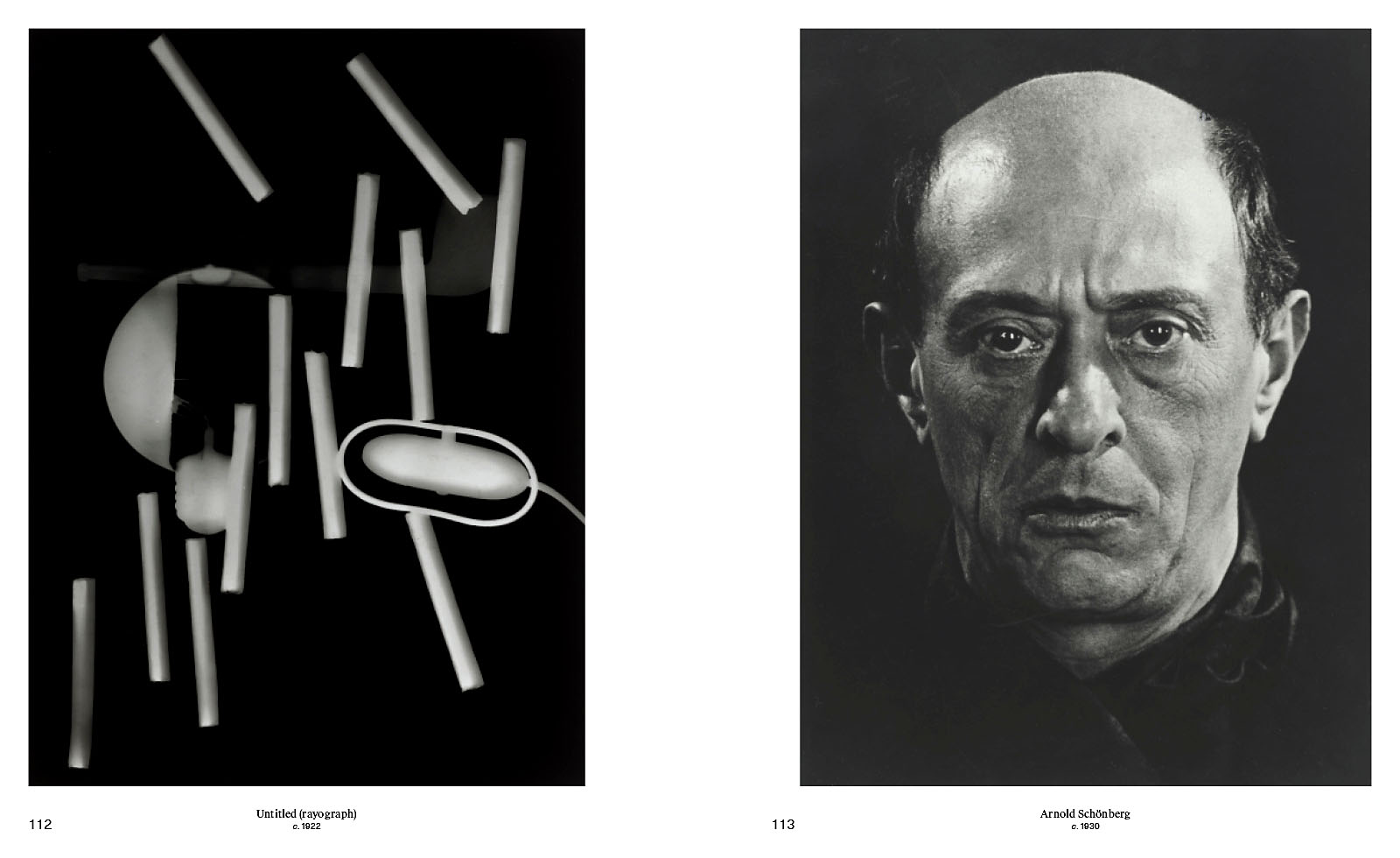

Man Ray. Liberating Photography book pages

Photo Elysee

Place de la Gare 17

CH-1003 Lausanne

+41 21 318 44 00

Opening hours:

Monday : 10am – 6pm

Tuesday : closed (MCBA open)

Wednesday : 10am – 6pm

Thursday : 10am – 8pm

Friday : 10am – 6pm

Saturday : 10am – 6pm

Sunday : 10am – 6pm