Exhibition dates: 14th August – 25th October 2015

Curator: Dr Marta Weiss

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Portrait of Julia Margaret Cameron by her son

about 1870

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The road less travelled

It was a flying visit to Sydney to see the Julia Margaret Cameron exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The trip was so very worthwhile, for I had never seen JMC’s large contact photographs “in the flesh” before, let alone over 100 vintage prints from the Victoria and Albert Museum collection. They did not disappoint. This exhibition is one of the photographic highlights of the year.

When you think about it, here is one the world’s top ten photographers of all time – a woman, taking photographs within the first twenty five years of the birth of commercial photography, using rudimentary technology and chemicals – whose photographs are still up there with the greatest ever taken. Still recognisable as her own and no one else’s after all these years. That is a staggering achievement – and tells you something about the talent, tenacity and perspicacity of the women… that she possessed and illuminated such a penetrating discernment – a clarity of vision and intellect which provides a deep understanding and insight into the human condition.

Annie; ‘My first success’ (1864, below) points the way to the later development of her mature style. Although not entirely successful, the signature low depth of field and wonderful use of light are already present in this image. Compare this to Lady Adelaide Talbot (1865, below), only a year later, and you can see that her development as an artist is phenomenal. JMC pushes and pulls the face of the sitter within the image plane. In a sequence from the exhibition (enlarge the installation image, below) we have (from left to right), female in profile facing right with light from right Sappho (1865); female lower 2/3rds right with light from front above Christabel (1866); female looking at camera, soft, dark moody lighting hitting only one the side of the face and embroidered cap Zoe / Maid of Athens (1866); now a different tilt of the jaw, lighter print Beatrice (1866, below); a frontal portrait with dark background, pin sharp face and hair to the front and back of the face out of focus Julia Jackson (1867, below), then female portraits facing left, the head filling the upper left corner; looking down in three-quarter profile with light from the right, filling the frame; and then upper right, small face, with the rest falling off into darkness.

There is something so magical about how JMC can frame a face, emerging from darkness, side profile, filling the frame, top lit. Soft out of focus hair with one point of focus in the image. Beautiful light. Just the most sensitive capturing of a human being, I don’t know what it is… a glimpse into another world, a ghostly world of the spirit, the soul of the living seen now before they are dead.

While it is very interesting to see her failures, or what she perceived as her failures – not so much a failure of vision but mainly a failure of technique: cracking of the plates, under development, defective unmounted impressions – presented in the exhibition, plus all her techniques for developing and amending the photograph – double printing, reverse printing, scratching onto the negative and painting on the print (all techniques later used by the Pictorialists) – it is the low depth of field, wonderful tones and the quality of the light that so impresses with her work. Her portraits have a real but very fluid and ethereal presence. Material, maternal, touch, sublime, religious, allegorical, mythological, and beautiful. She would focus her lens until she thought is was beautiful “instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon.”

She has, of course, been seen as a precursor to Pictorialism, but personally I do not get that feeling from her photographs, even though the artists are using many of the same techniques. Her work is based on the reality of seeing beauty, whereas the Pictorialists were trying to make photography into art by emulating the techniques of etching and painting. While the form of her images owes a lot to the history of classical sculpture and painting, to Romanticism and the Pre-Raphaelites, she thought her’s was already art of the highest order. She did not have to mask its content in order to imitate another medium. Others, such as the curator of the exhibition Marta Weiss, see her as a proto-modernist, precursor to the photographs of Stieglitz and Sander and I would agree. There is certainly a fundamental presence to JMC’s photographs, so that when you are looking at them, they tend to touch your soul, the eyes of some of the portraits burning right through you; while others, others have this ambiguity of meaning, of feeling, as if removed from the everyday life.

Unfortunately, her legacy and her baton has not been taken up in contemporary photography, other than through her love child Sally Mann. One of the main problems with contemporary portrait photography, perhaps any type of contemporary photography, is that anything goes. And what goes is usually linked to the photographer’s desire. It is not about the reality of the subject, but just a refraction of the desires of the photographer reflected in the subject. Many photographers today are not real photographers at all… they are just a pimp to their own ideas. There is a 100% co-relation between their vision and their work which leaves no room for ambiguity. There is no longer the interesting and lovely space between what is attempted and how the photographer would like it to be, as in JMC. Where the shortcomings are welcomed (she embraced flaws, cracks, thumb prints) and it all seems a marvellous activity. She was dedicated to the task of extracting the beauty of this ambiguity, through taking hours preparing plates, through sitting, developing and washing. She took her shortcomings and folded them back into her work so that there seems to be a type of perfection to it. Of course, there isn’t. These fulfilled her photographic vision, a rejection of ‘mere conventional topographic photography – map-making and skeleton rendering of feature and form’ in favour of a less precise but more emotionally penetrating form of portraiture. By contrast, the surface in contemporary “topographic” photography is just a paper thin reflection of the photographer themselves, nothing more.

The road to spirituality is the road less travelled. It is full of uncertainty and confusion, but only through exploring this enigma can we begin to approach some type of inner reality. Julia Margaret Cameron, in her experiments, in her dogged perseverance, was on a spiritual journey of self discovery. In Philip Roth’s Exit Ghost, he suggests Richard Strauss’ Four Last Songs as the ideal music for a scene his character has written:

“Four Last Songs. For the profundity that is achieved not by complexity but by clarity and simplicity. For the purity of the sentiment about death and parting and loss. For the long melodic line spinning out and the female voice soaring and soaring. For the repose and composure and gracefulness and the intense beauty of the soaring. For the ways one is drawn into the tremendous arc of heartbreak. The composer drops all masks and, at the age of eighty-two, stands before you naked. And you dissolve.”

These words are an appropriate epithet for the effect of the photographs of Julia Margaret Cameron in this year 2015, the 200th anniversary of her birth.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

Word count: 1,336

.

Many thankx to the AGNSW and the Victoria and Albert Museum for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

NB: it would have been great to see more of the later work as this exhibition mainly focuses on the period 1864-1869 (probably the bulk of what is in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection). Also, in the expansive, open galleries, some colour on the walls would have been good. When JMC exhibited her work it would have been on coloured walls, probably with multiple mounts of different colours as well. It would also have been nice to see some of the signatures on the work, as some of them reveal intimate facts about the sitter/theme.

When Cameron photographed her intellectual heroes such as Alfred Tennyson, Sir John Herschel and Henry Taylor, her aim was to record ‘the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man.’

‘When I have such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavoured to do its duty towards them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man. The photograph thus taken has been almost the embodiment of a prayer’.

.

Julia Margaret Cameron 1867

‘When … coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon’.

.

Julia Margaret Cameron

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Mrs. Herbert Duckworth

1872

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Julia Margaret Cameron’s powerful portraits of her niece and goddaughter Julia Jackson depict her as herself, rather than a religious or literary character. Cameron generally reserved this approach for her male sitters. This is one of a series of portraits in which the dramatically illuminated Jackson fearlessly returns the camera’s gaze. Cameron’s niece, here given her married name, once again regards the camera directly, but with an air of sadness rather than confidence. Her husband had died after just three years of marriage. Cameron inscribed one version of this photograph ‘My own cherished Niece and God Child / Julia Duckworth / a widow at 24’.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Annie; ‘My first success’

1864

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Julia Margaret Cameron was 48 when she received a camera as a gift from her daughter and son-in-law. It was accompanied by the words, ‘It may amuse you, Mother, to try to photograph during your solitude at Freshwater.’ Cameron had compiled albums and even printed photographs before, but her work as a photographer now began in earnest. Cameron made this portrait of Annie Philpot, the daughter of a local family, within a month of receiving her first camera. She inscribed some prints of it ‘My first success’ and later wrote of her excitement, ‘I was in a transport of delight. I ran all over the house to search for gifts for the child. I felt as if she entirely had made the picture.’

Cameron’s mentor and friend, the artist G.F. Watts wrote to Cameron, ‘Please do not send me valuable mounted copies … send me any … defective unmounted impressions, I shall be able to judge just as well & shall be just as much charmed with success & shall not feel that I am taking money from you.’ This is one of approximately 67 in the V&A’s collection that was recently discovered to have belonged to him. Many are unique, which suggests that Cameron was not fully satisfied with them. Some may seem ‘defective’ but others are enhanced by their flaws. All of them contribute to our understanding of Cameron’s working process and the photographs that did meet her standards.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Lady Adelaide Talbot

May 1865

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Julia Margaret Cameron, 28 & 31 July 1865

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In this close-up profile, Lady Talbot gazes out of the frame with determination. Instead of a tangle of branches and leaves, the background is neutral. The focus is soft and the light coming from the right traces the sitter’s profile. This photograph looks more distinctively like the work of Julia Margaret Cameron and shows the development of her signature style.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Il Penseroso; Come pensive nun devout and pure, Sober, stedfast and demure; Portrait or rather Study of Lady Adelaide Talbot

May 1865

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Julia Margaret Cameron, 27 September 1865

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Here Lady Adelaide Talbot appears not as herself, but as Melancholy, the personification of pensive sadness, that John Milton evoked in his poem Il Penseroso (about 1631). Draped in a shawl that hides her everyday clothing, her hands form a V on her chest, in a theatrical gesture. Cameron inscribed this print with two lines from the poem, ‘Come pensive Nun, devout and pure, / Sober, stedfast, and demure’.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Christiana Fraser-Tytler

c. 1864-1865

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Mrs Margaret Southam, 1941

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Christiana Fraser-Tytler modelled for other Julia Margaret Cameron photographs together with her sisters. One of them, Mary, an artist and designer, later married the artist G.F. Watts. This print originally belonged to either Watts or his wife. It came from the Watts estate, which was sold after Mary’s death in 1938.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Sappho

1865

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Alan S. Cole, 19 April 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In late 1865 Julia Margaret Cameron began using a larger camera, which held a 15 x 12-inch glass negative. Early the next year she wrote to Henry Cole with great enthusiasm – but little modesty – about the new turn she had taken in her work. Cameron initiated a series of large-scale, close-up heads. These fulfilled her photographic vision, a rejection of ‘mere conventional topographic photography – map-making and skeleton rendering of feature and form’ in favour of a less precise but more emotionally penetrating form of portraiture.

This striking version of Sappho is in keeping with Cameron’s growing confidence as an artist. Mary Hillier’s classical features stand out clearly in profile while her dark hair merges with the background. The decorative blouse balances the simplicity of the upper half of the picture. Cameron was clearly pleased with the image since she printed multiple copies, despite having cracked the negative.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Christabel

1866

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Alan S. Cole, 19 April 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The title refers to a poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge about a virtuous maiden who is put under a spell by an evil sorceress. Cameron wrote of photographs such as this, ‘when … coming to something which, to my eye, was very beautiful, I stopped there instead of screwing on the lens to the more definite focus which all other photographers insist upon’.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Beatrice

1866

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Alan S. Cole, 19 April 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Cameron based the pose, drapery, and sad expression of her model on a painting attributed to Guido Reni. The subject is the 16th-century Italian noblewoman Beatrice Cenci who was executed for arranging the murder of her abusive father. One review admired Cameron’s soft rendering of ‘the pensive sweetness of the expression of the original picture’ while another mocked her for claiming to have photographed a historical figure ‘from the life’.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Julia Jackson

1867

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Mrs Margaret Southam, 1941

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Cameron’s powerful portraits of her niece and goddaughter Julia Jackson depict her as herself, rather than a religious or literary character. Cameron generally reserved this approach for her male sitters. This is one of a series of portraits in which the dramatically illuminated Jackson fearlessly returns the camera’s gaze.

Cameron’s good friend Anne Thackeray Ritchie recalled in 1893, ‘Sitting to her was a serious affair, and not to be lightly entered upon. We came at her summons, we trembled (or we should have trembled had we dared to do so) when the round black eye of the camera was turned upon us, we felt the consequences, what a disastrous waste of time and money and effort, might ensue from any passing quiver of emotion.’

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Hosanna

1865

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Vivien and Merlin from Illustrations to Tennyson’s Idylls of the King

1874

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Vivien and Merlin from Illustrations to Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (detail)

1874

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Installation views of the exhibition Julia Margaret Cameron: from the Victoria and Albert Museum, London at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney

Photos: Marcus Bunyan

Julia Margaret Cameron’s career as a photographer began in 1863 when her daughter gave her a camera. Cameron began photographing everyone in sight. Because of the newness of photography as a practice, she was free to make her own rules and not be bound to convention. The kinds of images being made at the time did not interest Cameron. She was interested in capturing another kind of photographic truth. Not one dependent on accuracy of sharp detail, but one that depicted the emotional state of her sitter.

Cameron liked the soft focus portraits and the streak marks on her negatives, choosing to work with these irregularities, making them part of her pictures. Although at the time Cameron was seen as an unconventional and experimental photographer, her images have a solid place in the history of photography.

Most of Cameron’s photographs are portraits. She used members of her family as sitters and made photographs than concentrated on their faces. She was interested in conveying their natural beauty, often asking female sitters to let down their hair so as to show them in a way that they were not accustomed to presenting themselves. In addition to making stunning and evocative portraits both of male and female subjects, Cameron also staged tableaux and posed her sitters in situations that simulated allegorical paintings.

Text from the Victoria and Albert Museum website

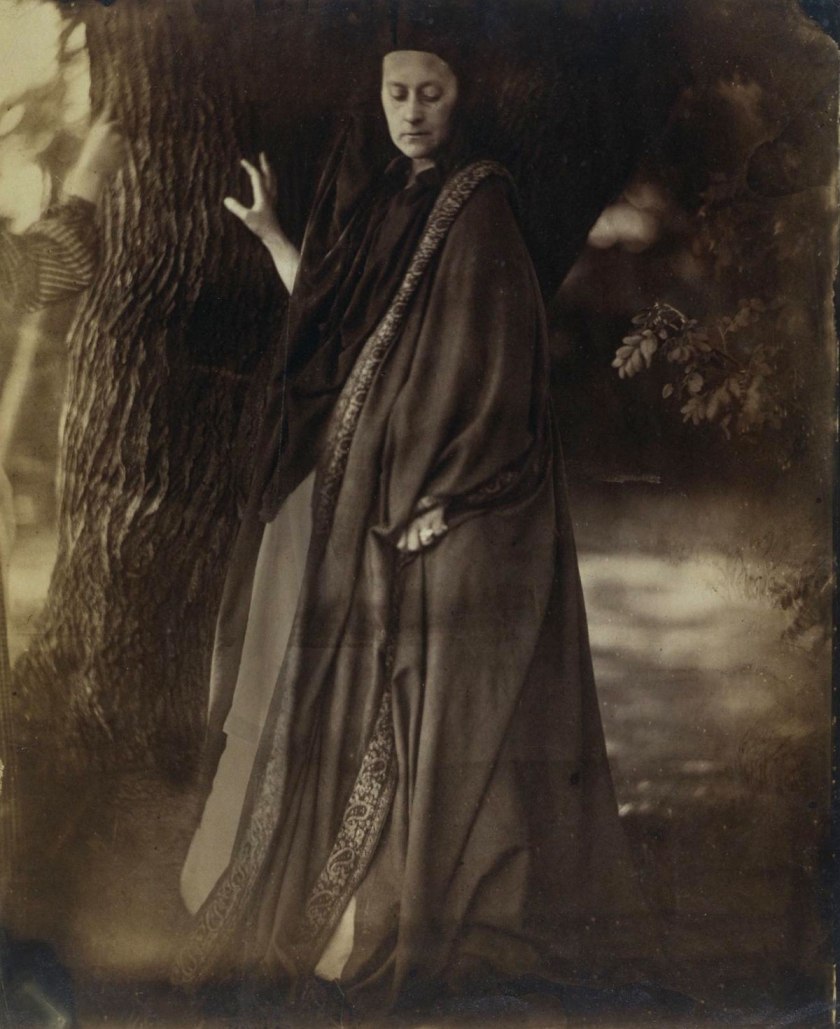

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Lady Elcho / A Dantesque Vision

1865

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Mrs Margaret Southam, 1941

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Julia Margaret Cameron’s earliest photographic subjects were family and friends, many of whom were eminent literary figures. These early portraits reveal how she experimented with dramatic lighting and close-up compositions, features that would become her signature style. In May 1865 Cameron used her sister’s London home, Little Holland House, as her photographic headquarters. Her sister Sara Prinsep, together with her husband Thoby, had established a cultural salon there centred around the artist George Frederic Watts, who lived with them. Cameron photographed numerous members of their circle on the lawn. These included artists, writers and collectors and Henry Cole, the director of the South Kensington Museum.

Cameron clothed Lady Elcho in flowing draperies to suggest a character out of Dante, author of the 14th-century poem the Divine Comedy. Cameron wears the same large, paisley-edged shawl in the portrait by her son. The fragmented female figure at the far left of the frame may have been assisting Cameron.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

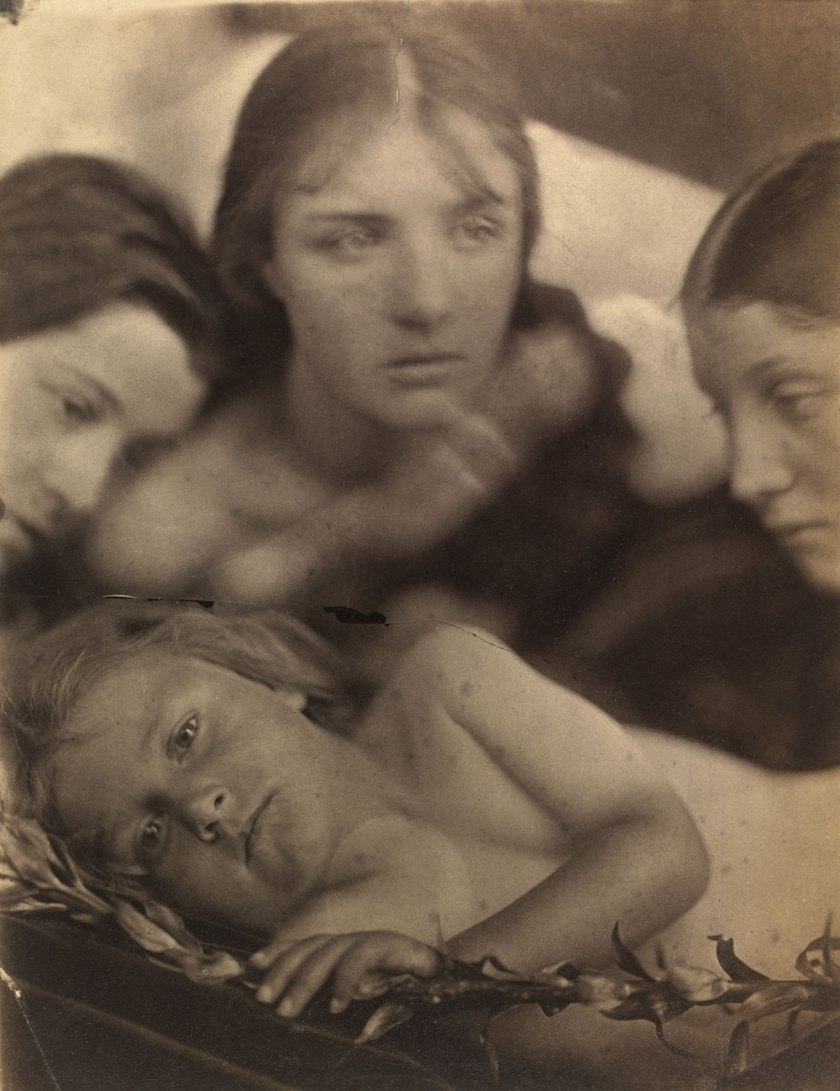

Resting in Hope; La Madonna Riposata

1864

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Purchased from Julia Margaret Cameron, 17 June 1865

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Many of the photographs purchased by the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) from Julia Margaret Cameron were ‘Madonna Groups’ depicting the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ. Her housemaid Mary Hillier posed as the Virgin Mary so often she became known locally as ‘Mary Madonna’. Like many of her contemporaries, Cameron was a devout Christian. As a mother of six, the motif of the Madonna and child held particular significance for her. In aspiring to make ‘High Art’, Cameron aimed to make photographs that could be uplifting and morally instructive.

As in many of Cameron’s depictions of the subject, the Madonna is holding a sleeping child. This had practical advantages as the infant was less likely to move during the long exposure. It was also suggestive of death, a grim reality for many Victorian families and a reference to the Pietà, a subject in Christian art in which the Virgin Mary cradles the dead Christ.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

The Shadow of the Cross

August 1865

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Julia Margaret Cameron, 27 September 1865

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

With the addition of a small wooden cross and female model in drapery, Cameron transformed a portrait of her sleeping grandson into an image of the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ. The mother leaning over the child prefigures Mary mourning over the body of her son, who had died on the cross. The framed pictures and curtain in the background reveal the setting as a domestic interior.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Devotion

1865

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Julia Margaret Cameron, 27 September 1865

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In this unusual horizontal composition, the close-up figures of the sleeping Christ child and the Madonna nearly fill the frame. The title suggests both Christian concepts and the theme of motherhood. Next to the title Cameron wrote: ‘From Life My Grand child age 2 years & 3 months’, making the image simultaneously a religious study and a family portrait.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

St. Agnes

1864

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Purchased from Julia Margaret Cameron, 17 June 1865

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This image may have been inspired by poems by Alfred Tennyson and John Keats based on the legend that virgins dream of their future husbands on St Agnes Eve (20 January). To suggest the night, Julia Margaret Cameron printed the photograph dark and added a moon by hand. The sitter is Mary Hillier, Cameron’s housemaid and one of her ‘most beautiful and constant’ models.

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

The Dream

1869

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Alan S. Cole, 19 April 1913

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

In 1869, Julia Margaret Cameron wrote to Sir Henry Cole, the founding director of the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) of the ‘cruel calamity … which has over taken 45 of my Gems – a honey comb crack extending over the picture appearing at any moment and beyond any power to arrest.’ Cameron blamed her ‘fatally perishable’ photographic chemicals, while members of the Photographic Society suspected the damp climate of the Isle of Wight. Today’s theory is that failure to sufficiently wash the negatives after fixing them caused the problem.

John Milton’s poem On his deceased Wife (about 1658) tells of a fleeting vision of his beloved returning to life in a dream. On this mount she included G. F. Watts’ assessment: ‘quite divine’. Cameron was particularly distraught by the crackling that befell this negative. She seemed not to be bothered, however, by the two smudged fingerprints in the lower right, which form a kind of inadvertent signature.

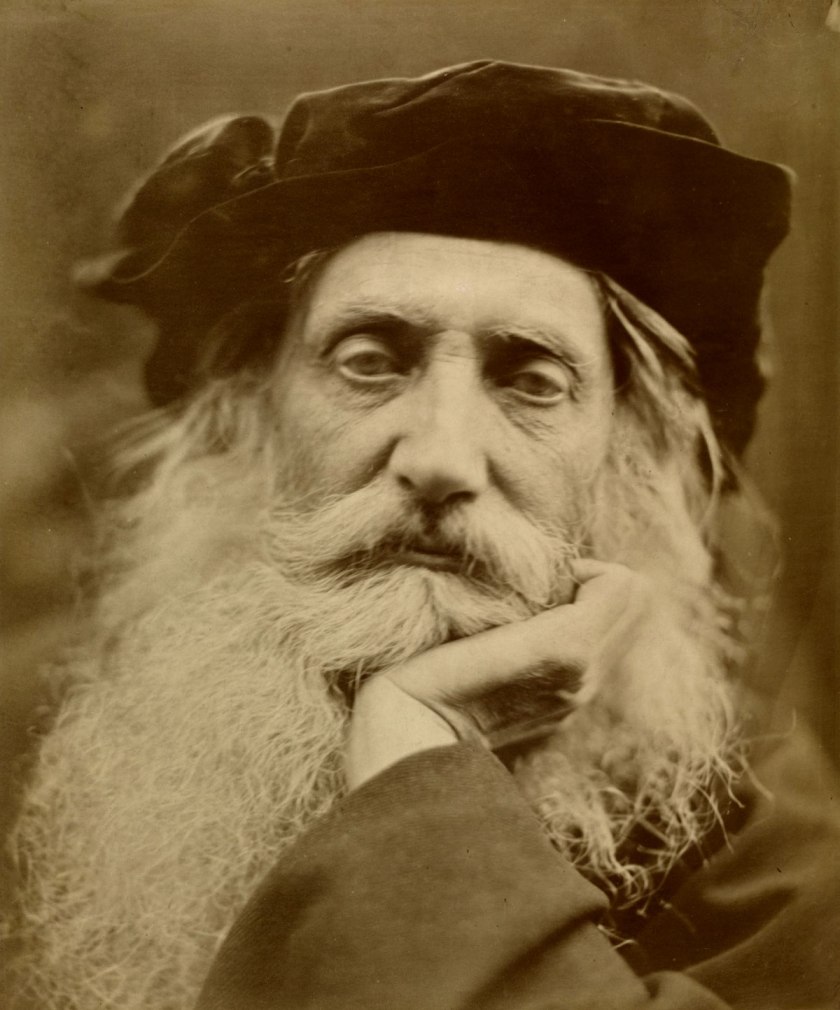

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Henry Taylor

October 10, 1867

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Window & Grove, 1963

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

When Julia Margaret Cameron photographed her intellectual heroes such as Alfred Tennyson, Sir John Herschel and Henry Taylor, her aim was to record ‘the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man.’ Another motive was to earn money from prints of the photographs, since her family’s finances were precarious. Within her first year as a photographer she began exhibiting and selling through the London gallery Colnaghi’s. She used autographs to increase the value of some portraits.

For this portrait of her close friend, the playwright and poet Taylor, Cameron broke from her practice of photographing male heads emerging from darkness. As with some of her female heads, the sitter’s face fills the frame, while his sleeve and beard flow beyond its confines.

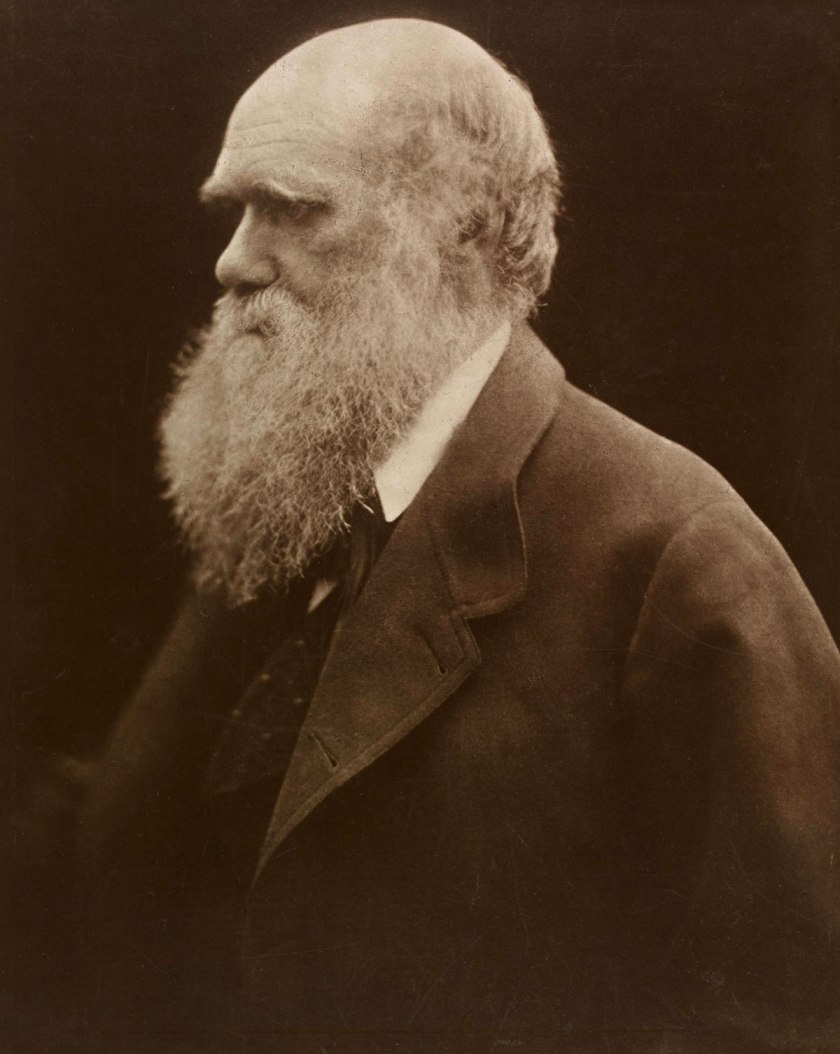

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Charles Darwin

1868; printed 1875

Carbon print from copy negative

Given by Mrs Ida S. Perrin, 1939

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The naturalist Charles Darwin and his family rented a cottage in Freshwater from the Camerons in the summer of 1868. By 27 July, Colnaghi’s was advertising, ‘we are glad to observe her gallery of great men enriched by a very fine portrait of Charles Darwin’. Due to the sitter’s celebrity, Cameron later had this portrait reprinted as a more stable carbon print. When Cameron photographed her intellectual heroes such as Alfred Tennyson, Sir John Herschel and Henry Taylor, her aim was to record ‘the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man.’

Julia Margaret Cameron (British, 1815-1879)

Portrait of Herschel

April 1867

Albumen print from wet collodion glass negative

Given by Window & Grove, 1963

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Herschel was an eminent scientist who made important contributions to astronomy and photography. Cameron wrote of this sitting, ‘When I have such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavoured to do its duty towards them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man. The photograph thus taken has been almost the embodiment of a prayer.’

Art Gallery of New South Wales

Art Gallery Road, The Domain

Sydney NSW 2000, Australia

Opening hours:

Open every day 10am – 5pm

except Christmas Day and Good Friday

You must be logged in to post a comment.