Exhibition dates: 28th June – 5th October 2014

Installation view of the exhibition The Museum of Photography. A Revision at Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest

The ghost of the photography museum. The ghost of the machine.

Marcus

.

Many thankx to Museum Ludwig for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

Installation views of the exhibition The Museum of Photography. A Revision at Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest

Marcus A. Root (American, 1808-1888)

Daguerreotype of a Mother and Child

1840

Museum Ludwig

Photo: © Rhenish image archive

Marcus A. Root

Born in Granville, Ohio in 1808, Marcus Aurelius Root moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in the early 1830s to study painting with Thomas Sully. Sully’s lack of enthusiasm for his pupil’s artistic skills led Root to open a penmanship school before he turned to the new medium of daguerreotyping as a way to earn his living. Root seems to have whole heartedly committed to this new endeavour since in 1844 he reportedly had daguerreotype studios in Mobile, AL; New Orleans, LA; St. Louis, MO; and Philadelphia. By 1845 he had resettled back in Philadelphia with a studio at 140 Chestnut Street. Root headed up one of the city’s most esteemed studios attracting well-known patrons including failed presidential candidates Henry Clay and Winfield Scott as well as local Philadelphians. In 1849 in partnership with his brother Samuel, he opened a New York City gallery located on Broadway and remained part of that business for several years.

In 1856 Marcus Root’s life took an unexpected turn when he was severely injured in a train accident. Root began writing a book, The Camera and the Pencil, during the long years spent recuperating from his accident. Published in 1864, The Camera and the Pencil provided a history of photography along with technical information about the medium, but primarily focused on promoting the aesthetics of the practice. Root wanted photographers to be considered equal to painters and argued for the importance of a pleasing studio environment for the sitters and an artistic eye for the operators. Good photography, Root argued, was not merely the successful mechanical operation of a piece of equipment. Root also wrote extensively for photographic journals including Philadelphia Photographer, Humphrey’s Journal of Photography and the Allied Arts and Sciences, and Photographic and Fine Arts Journal.

Anonymous. “Marcus Aurelius Root,” on the Luminous-Lint: History, Evolution and Analysis website [Online] Cited 20/06/2021.

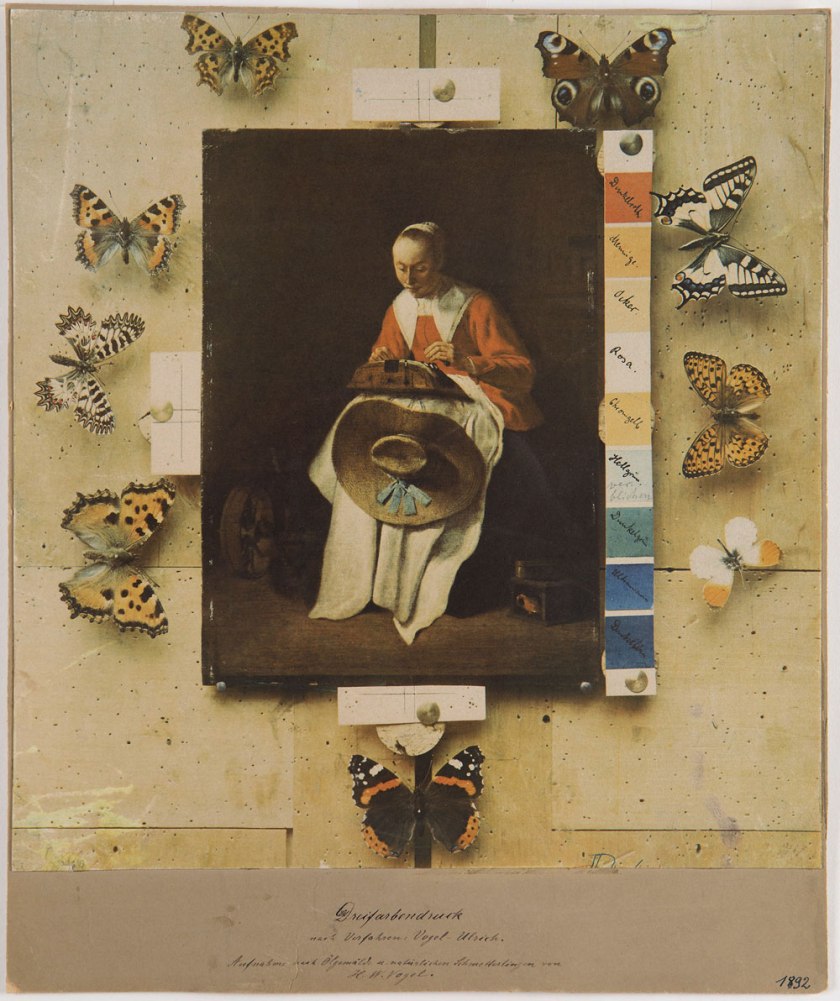

Hermann Wilhelm Vogel (German, 1834-1898)

Three-colour printing process by Bird Ulrich. Uptake by oil paintings and natural butterflies

1892

Museum Ludwig

Photo: © Rhenish image archive

Dye sensitization

In 1873 Vogel discovered dye sensitisation, a pivotal contribution to the progress of photography. The photographic emulsions in use at that time were sensitive to blue, violet and ultraviolet light, but only slightly sensitive to green and practically insensitive to the rest of the spectrum. While trying out some factory-made collodion bromide dry plates from England, Vogel was amazed to find that they were more sensitive to green than to blue. He sought the cause and his experiments indicated that this sensitivity was due to a yellow substance in the emulsion, apparently included as an anti-halation agent. Rinsing it out with alcohol removed the unusual sensitivity to green. He then tried adding small amounts of various aniline dyes to freshly prepared emulsions and found several dyes which added sensitivity to various parts of the spectrum, closely corresponding to wavelengths of light the dyes absorbed. Vogel was able to add sensitivity to green, yellow, orange and even red.

This made photography much more useful to science, allowed a more satisfactory rendering of coloured subjects into black-and-white, and brought actual colour photography into the realm of the practical.

In the early 1890s, Vogel’s son Ernst assisted German-American photographer William Kurtz in applying dye sensitisation and three-colour photography to halftone printing, so that full-colour prints could be economically mass-produced with a printing press.

Text from the Wikipedia website

Gustave Le Gray (French, 1820-1884)

Pier and lighthouse at Le Havre

1856

Museum Ludwig

Photo: © Rhenish image archive

“It is my deepest wish that photography, instead of falling within the domain of industry, of commerce, will be included among the arts. That is its sole, true place, and it is in that direction that I shall always endeavour to guide it. It is up to the men devoted to its advancement to set this idea firmly in their minds.”

Gustave Le Gray, 1852 edition of his treatise

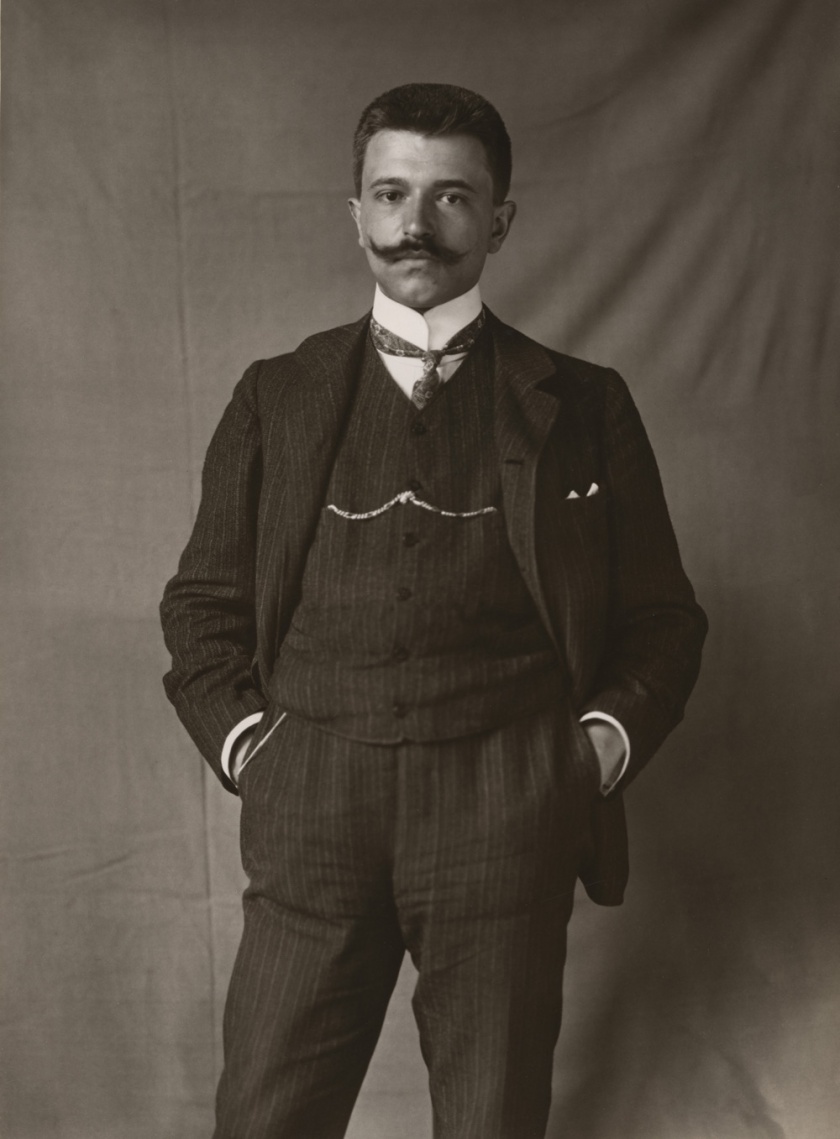

A ghost has been haunting podiums, periodicals, and arts pages for decades: the ghost of the photography museum. “We need one,” say advocates; “really?” counter opponents. Chemist Erich Stenger (1878-1957), a passionate collector of photographs, viewed them not as art, but as technological evidence. Yet the way he envisaged presenting them was in a museum. At an early date he called for the establishment of a (technology-based) museum of photography, accumulating items for it and drawing up a display plan. Among the first collectors of photography, he amassed holdings of nineteenth-century landscapes, portraits, photographs taken by airmen in World War I, portraits framed as decorative items, prizewinning pictures of animals from the first half of the twentieth century, caricatures about photography, and much else besides. As a scientist, Stenger collected data and represented it in the form of tables and diagrams. That is also how he ordered everything relating to photography that he could lay his hands on. He distinguished some one hundred categories, from architecture photography to trick photography. His museum was to resemble an encyclopedia of photography, and in that sense he was very much a man of the nineteenth century. He showed his collection at most major photography exhibitions held during his lifetime, including Pressa in Cologne in 1928.

Stenger’s collection is now integrated into the Agfa collection, which in turn forms an important part of the photography holdings at the Museum Ludwig. The items amassed by Stenger now therefore constitute a museum within a museum – within an art museum, in fact. How is an art museum to deal with a collection of this kind? Individual items and sections from it have been exhibited since the early years of the twentieth century. At the Museum Ludwig it has been represented in Facts (2006), Silber und Salz (Silver and Salt; 1988), An den süssen Ufern Asiens (On the Sweet Shores of Asia; 1989), and many other shows. Stenger’s ideas about his collection are now being spotlighted and presented under one roof. This seems appropriate at a time when museums and archives are the subject of heated debates and intensive self-examination. As institutions, they shape and regulate cultural memory; and photography in museums, in particular, influences our view of the past and the present. This function of the Stenger collection acquired semi-official status in 2005, when it was named a national cultural treasure. That is reason enough to subject it to a reappraisal, re-examining its contents, the criteria governing its accumulation, and the ways in which an art museum might want to approach it today.

The exhibition comprises approximately 250 photographs and objects.

Press release from Museum Ludwig website

Unknown photographer

Portrait Erich Stenger

1906

Museum Ludwig

Photo: © Rhenish image archive

Henry Traut (English, 1857-1940)

Portrait, Munich

1932

Museum Ludwig

Photo: © Rhenish image archive

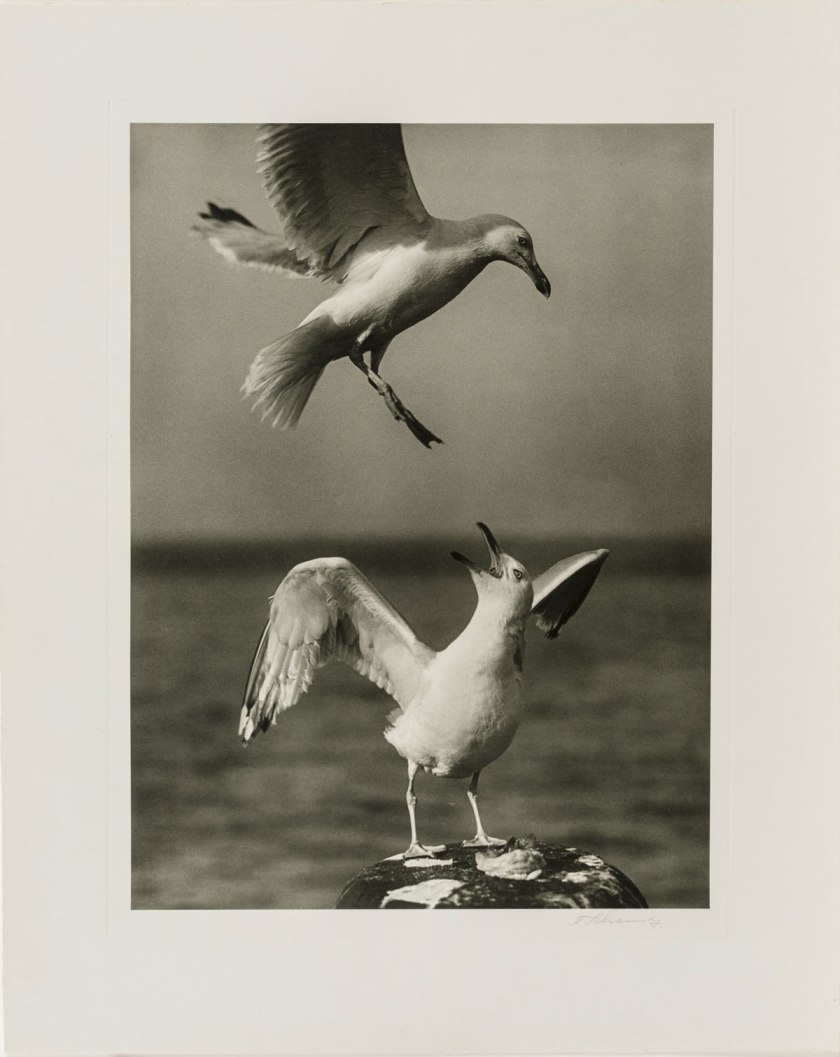

Franz Schensky (German, 1871-1957)

Möwenpaar

1930

Museum Ludwig

Photo: © Rhenish image archive

Franz Schensky

The Helgoländer Franz Schensky one of the pioneers of black and white photography and has a firm place in the German photo-story. In 2003, 1,400 of his glass negatives, believed to be lost, were found in a cellar on Helgoland and processed and digitised by the Museum Helgoland and the museum’s friends’ association in a special laboratory. The focus of these photographs from the period between 1900 and 1950 are the areas of old Heligoland, aquarium, sea and waves, sailing, destruction and reconstruction, people and time in Schleswig.

Franz Grainer (Bavarian, 1871-1948)

Portrait

1920

Museum Ludwig

Photo: © Rhenish image archive

Franz Grainer

Grainer created numerous portraits of the children of the last crown prince of Bavaria, Rupprecht, especially the firstborn Luitpold and the son Albrecht, who was the only one to reach adulthood. In 1919, he was one of the founding members of the Gesellschaft Deutscher Lichtbildner (GDL), the predecessor of the German Academy of Photographs, whose chairmanship he later took over and still held in the power takeover of the National Socialists.

In addition to portrait photographs, more and more nude studies emerged in the 1920s. Works by Grainer are held at the Museum Folkwang in Essen and the Fotomuseum in the Munich Stadtmuseum.

Unknown artist

Template for a photomontage (Royal Bavarian Infantry Regiment)

2nd half of the 19th century

Museum Ludwig

Photo: © Rhenish image archive

Museum Ludwig

Heinrich-Böll-Platz

50667 Köln

Phone +49 221 221 26165

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Sunday 10am – 6pm

Closed Mondays

You must be logged in to post a comment.