Exhibition dates: 1st April – 24th July 2016

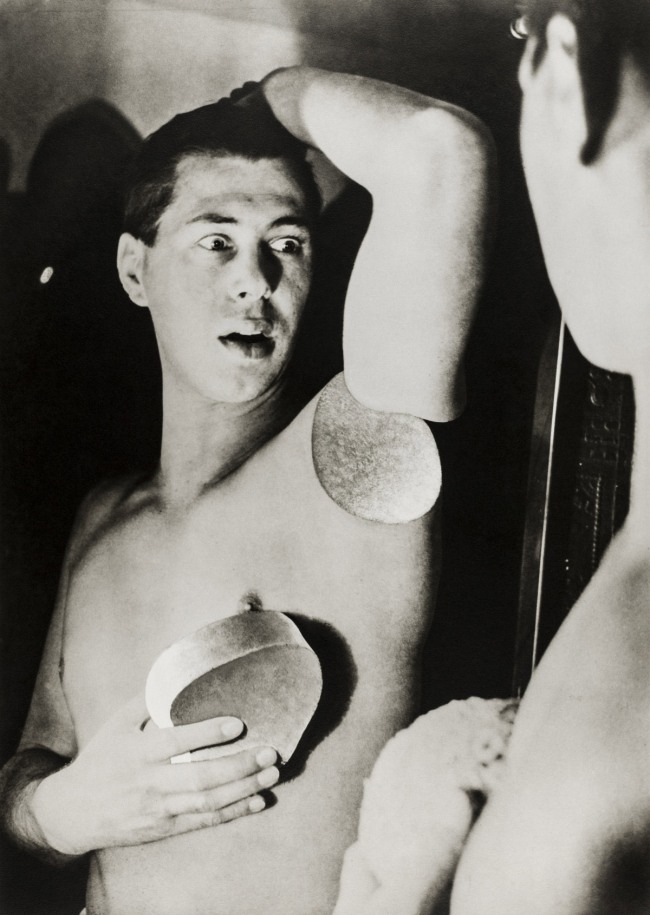

Albert Renger-Patzsch (German, 1897-1966)

Self portrait

1926/1927

Gelatin silver paper

16.9 x 22.8cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder, München

© Albert Renger Patzsch Archiv / Ann und Jürgen Wilde, Köln / 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich

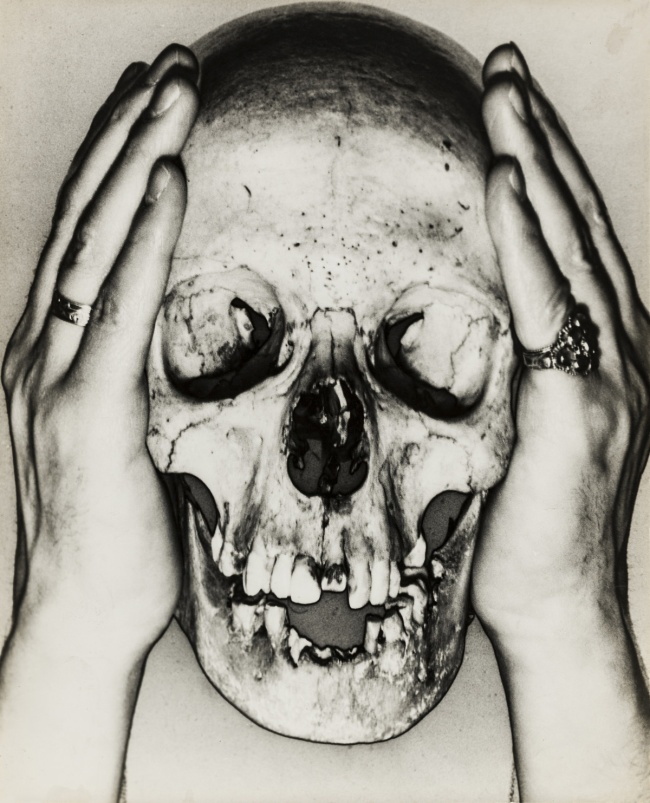

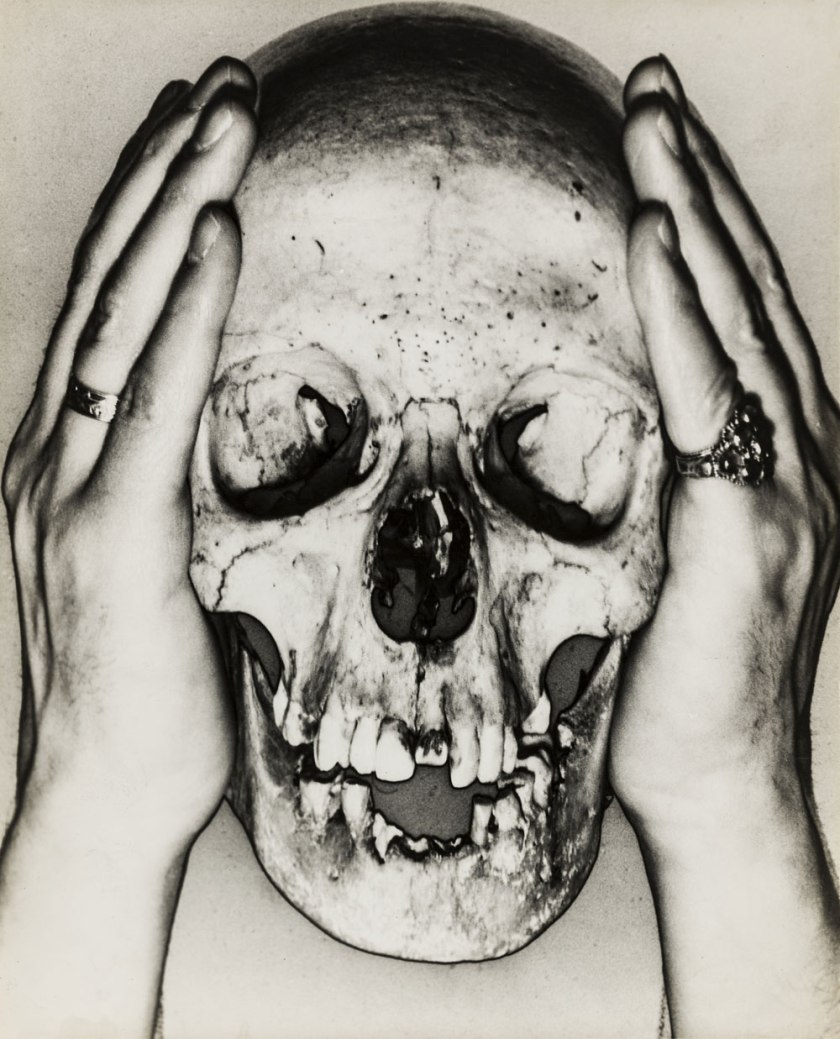

I loved putting the Florence Henri and the skull together. Too exhausted after a long day at work to say much else!

Marcus

Many thankx to Museum Bellerive for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image.

“I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak.”

André Breton

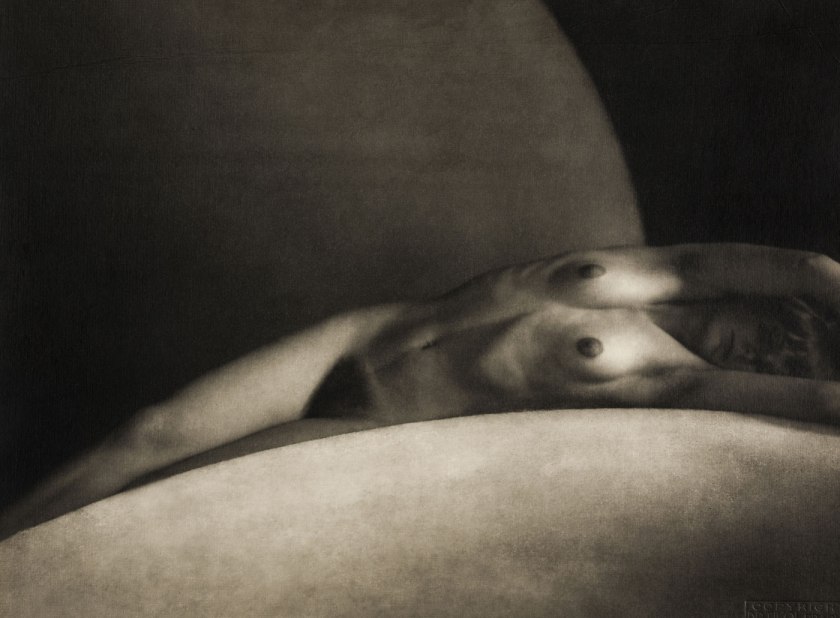

František Drtikol (Czech, 1883-1961)

Kreissegment [Bogen] / Circular segment (arch)

1928

Pigment print

21.3 x 28.7cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder, München

© František Drtikol – heirs, 2015

Brassaï (Hungarian-French, 1899-1984)

Gelegenheitsmagie (Keimende Kartoffel) / Occasional magic (Germinating potato)

1931

Gelatin silver print

Foto: © ESTATE BRASSAÏ – RMN

Grete Stern (Argentinian born Germany, 1904-1999)

The Eternal eye / Das Ewige Auge

c. 1950

Photomontage

Gelatin silver paper

39.5 x 39.5cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder, München

© Estate of Grete Stern Courtesy Galeria Jorge Mara – La Ruche, Buenos Aires, 2015

Grete Stern (Argentinian born Germany, 1904-1999)

In 1930 Stern and Ellen Rosenberg Auerbach founded ringl+pit, a critically acclaimed, prize-winning Berlin based photography and design studio. They used equipment purchased from Peterhans and became well known for innovative work in advertising. The name ringl+pit is from their childhood nicknames (Ringl for Grete, Pit for Ellen).

Intermittently between April 1930 and March 1933, Stern continued her studies with Peterhans at the Bauhaus photography workshop in Dessau, where she met the Argentinian photographer Horacio Coppola. In 1933 the political climate of Nazi Germany led her to emigrate with her brother to England, where Stern set up a new studio, soon to resume her collaboration there with Auerbach.

Stern first traveled to Argentina in the company of her new husband, Horacio Coppola in 1935. The newlyweds mounted an exhibition in Buenos Aires at Sur magazine, which according to the magazine, was the first modern photography exhibition in Argentina. In 1958, she became a citizen of Argentina.

In 1948 Stern began working for Idilio, an illustrated women’s magazine, targeted specifically at lower / lower-middle class women. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Stern created Los Sueños as illustrations for the woman’s magazine Idilio and its column “El psicoanálisis te ayudará” (Psychoanalysis Will Help You). Readers were encouraged to submit their dreams to be analysed by the ‘experts’ as an aid for its readers to find “self-knowledge and self-aid that would help them succeed in love, family and work”. Each week, one dream would be selected, analysed in depth by the expert, Richard Rest, and then illustrated by Stern through photomontage. Stern created about 150 of these photomontages, of which only 46 survive in negatives. Stern’s photomontages are surreal interpretations of the readers’ dreams that often subtly pushed back on the traditional values and concepts in Idilio magazine by inserting feminist critique of Argentinian gender roles and the psychoanalytic project in her images. The Idilio series has often been compared to Francisco Goya’s Sueños drawings, a series of preliminary drawings for his later body of work, Los Caprichos; they have also been directly compared to Los Caprichos themselves.

Stern provided photographs for the magazine and served for a stint as a photography teacher in Resistencia at the National University of the Northeast in 1959 and continued to teach until 1985.

In 1985, she retired from photography, but lived another 14 years until 1999, dying in Buenos Aires on 24 December at the age of 95.

Text from the Wikipedia website

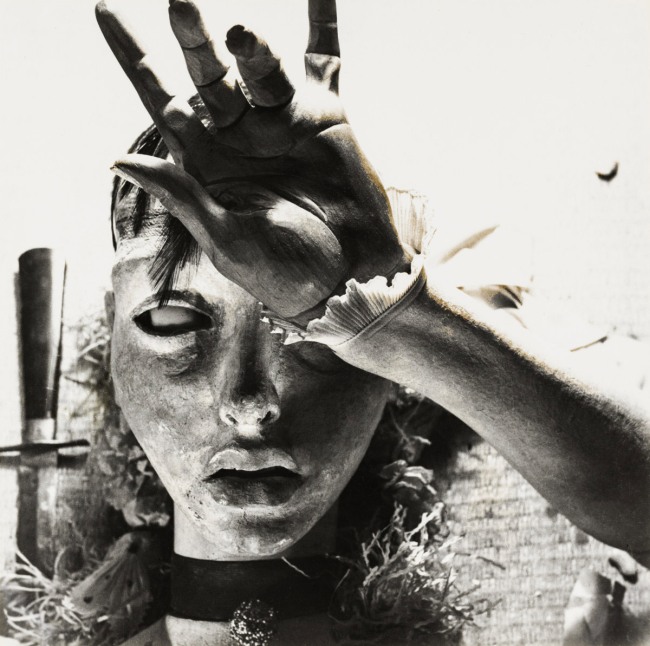

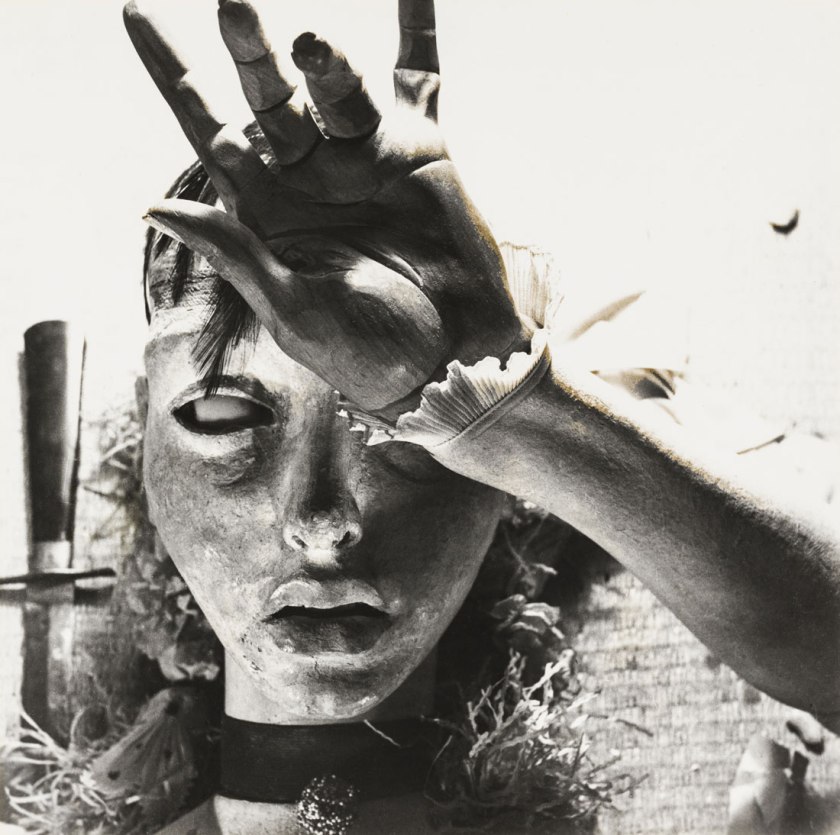

Hans Bellmer (German, 1902-1975)

The Doll / Die Puppe

1935

Gelatin silver paper

17.4 x 17.9cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder, München

© 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich

Avant-garde photographs seem like pictures from a dream world. From new kinds of compositions and perspectives to photomontage, technical experiments, and staged scenes, Real Surreal offers a chance to rediscover the range and multifacetedness of photography between the real and the surreal. The exhibition leads the visitor through the Neues Sehen (New Vision) movement in Germany, Surrealism in France, and the avant-garde in Prague. Thanks to rare original prints from renowned photographers between 1920 and 1950, this exhibition offers a chance to see these works in a new light. In addition to some 220 photographs, a selection of historical photography books and magazines as well as rare artists’ books allow visitors to immerse themselves in this new view of the world. Furthermore, examples of films attest to the fruitful exchanges between avant-garde photography and cinema during this time.

An exhibition in cooperation with the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg

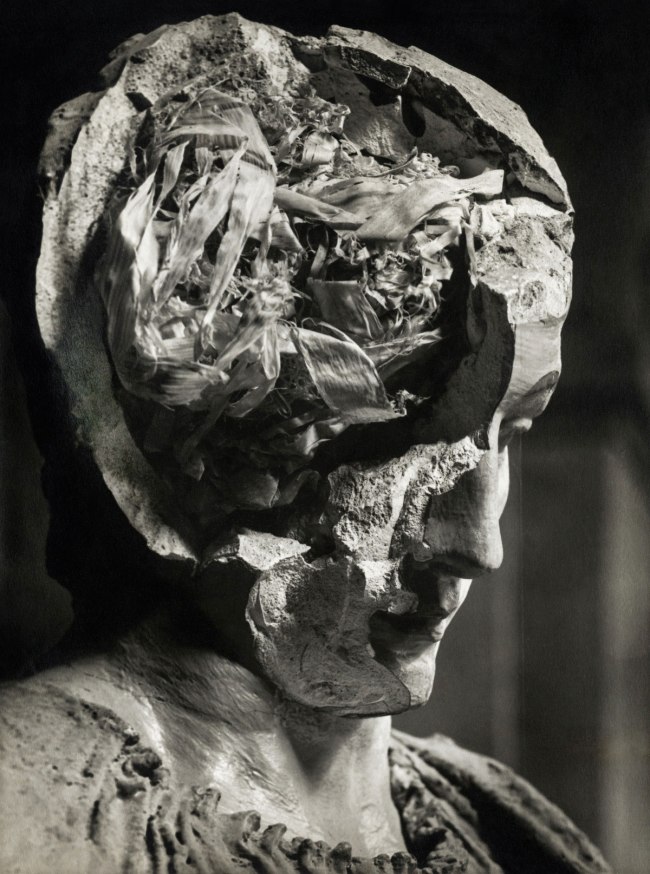

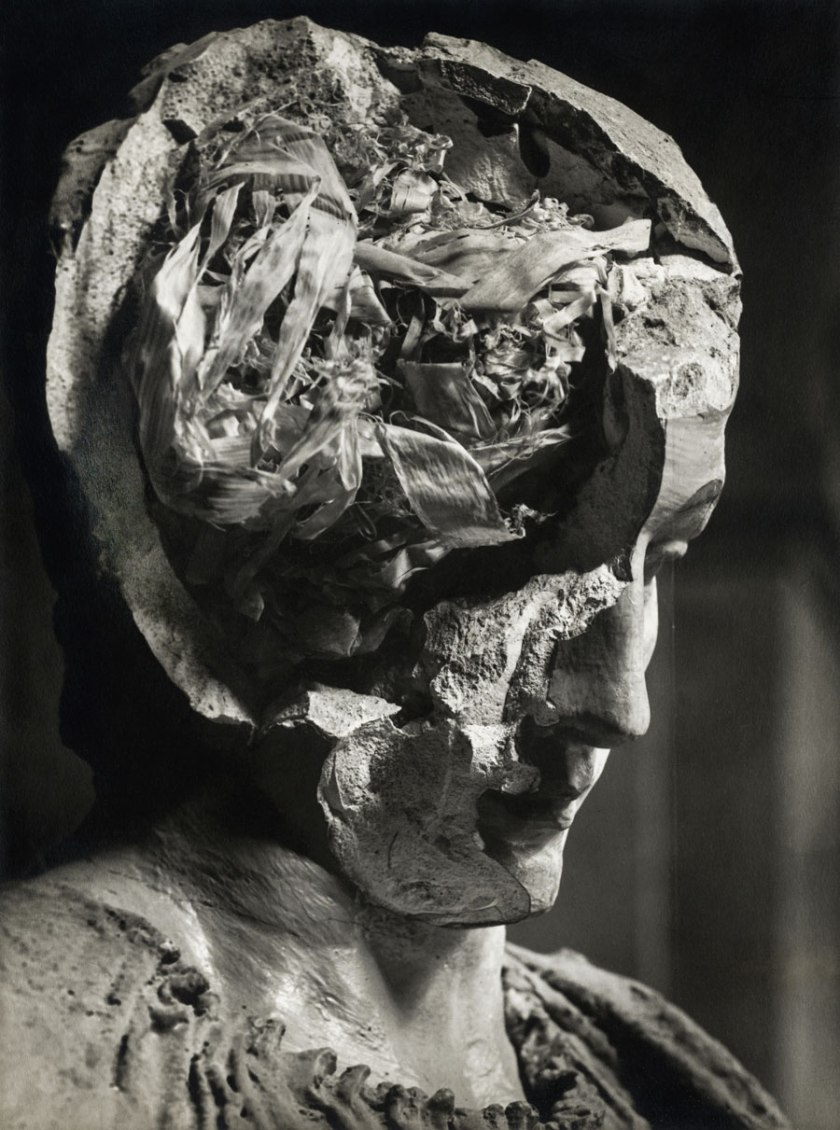

Josef Sudek (Czech, 1896-1976)

Gipskopf / Plaster head

c. 1947

Gelatin silver print

Foto: © Estate of Josef Sudek

Florence Henri (Swiss born United States, 1893-1982)

Porträtkomposition (Erica Brausen)

1931

Foto: © Galleria Martini and Ronchetti, Genova, Italy

Erwin Blumenfeld (American born Germany, 1897-1969)

Totenschädel / Skull

1932/1933

Foto: © The Estate of Erwin Blumenfeld

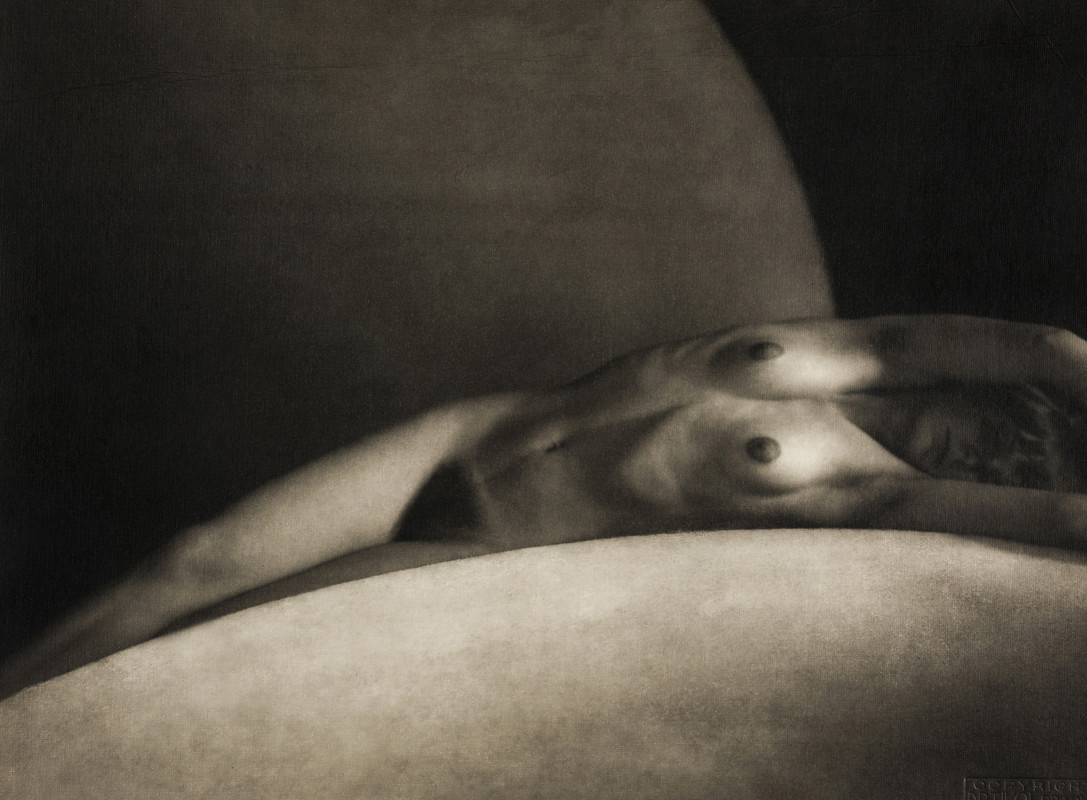

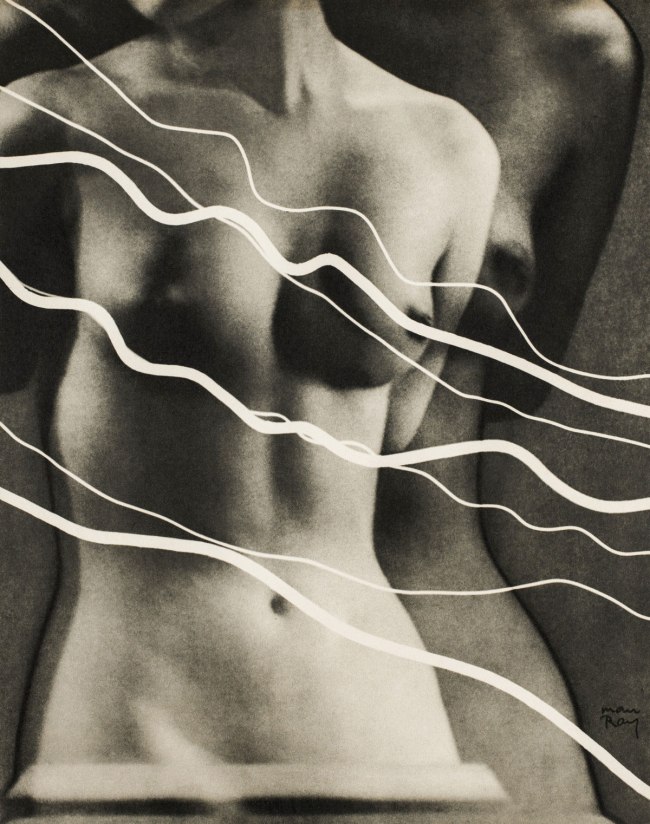

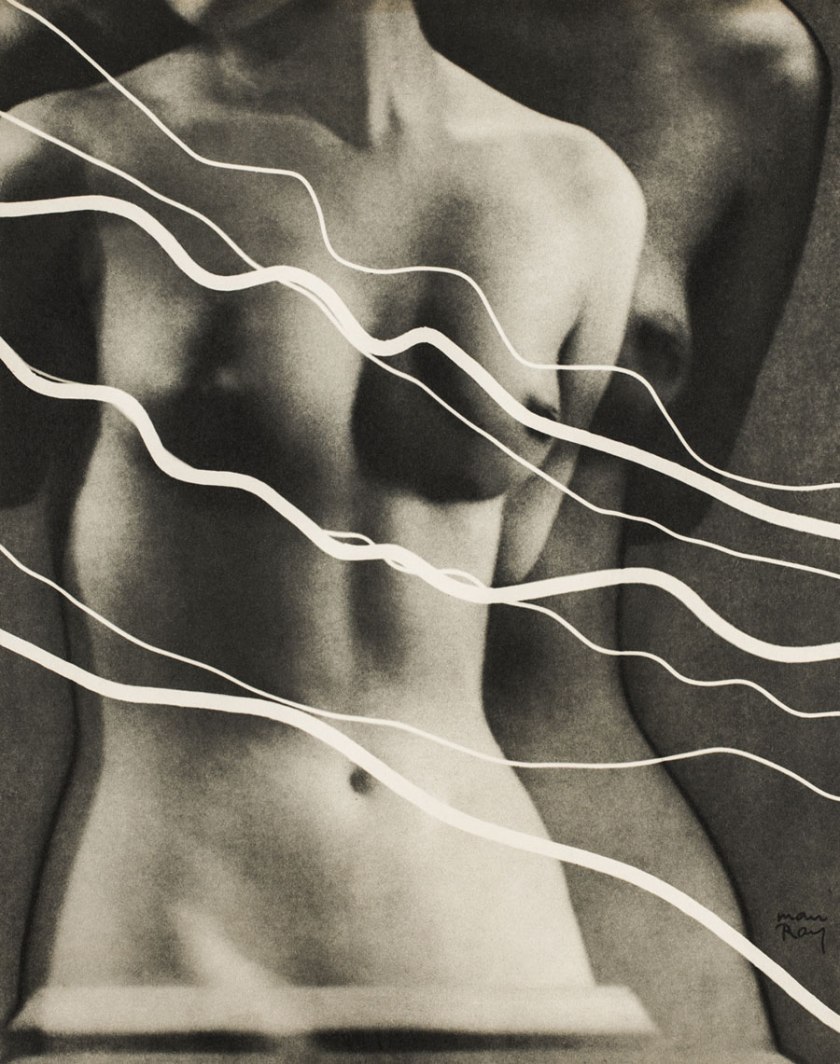

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Electricity

1931

Photoengraving

26 x 20.6cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder, München

© Man Ray Trust / 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich

Man Ray (American, 1890-1976)

Rayograph (spiral)

1923

Photogram

Gelatin silver paper

26.6 x 21.4cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder, München

© Man Ray Trust / 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich

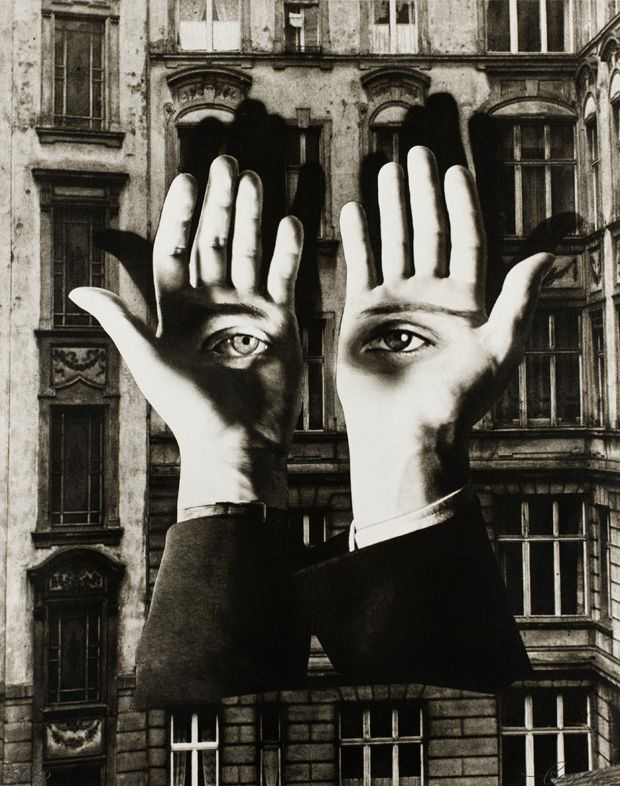

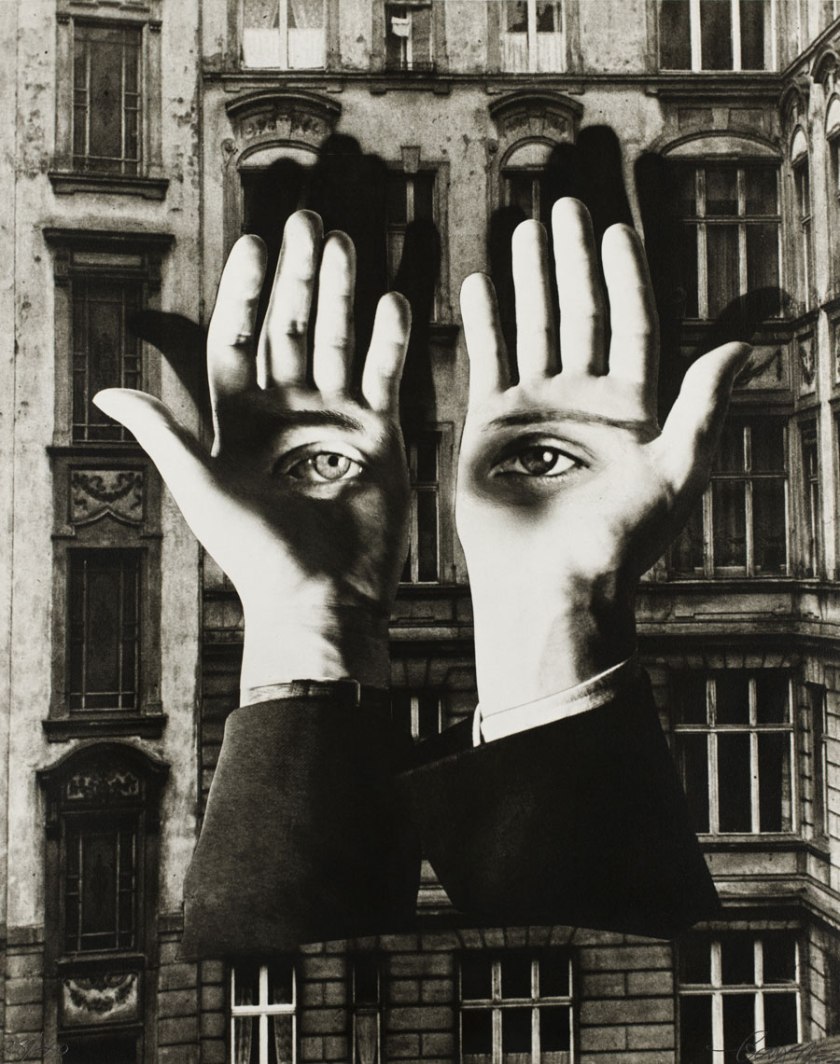

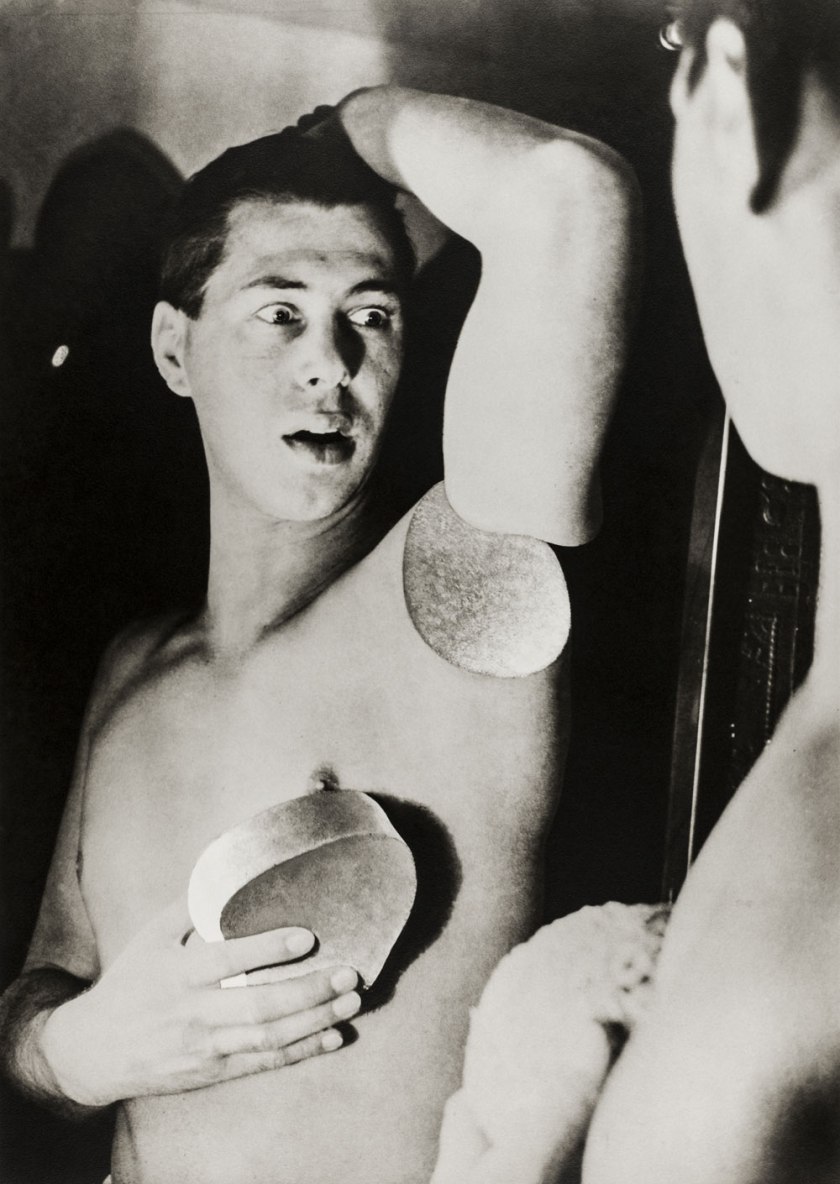

Herbert Bayer (American born Austria, 1900-1985)

Einsamer Grossstädter / Lonely city slickers

1932/1969

Photomontage

Gelatin silver paper

35.3 x 28cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder, München

© 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich

Artistic polymath Herbert Bayer was one of the Bauhaus’s most influential students, teachers, and proponents, advocating the integration of all arts throughout his career. Bayer began his studies as an architect in 1919 in Darmstadt. From 1921 to 1923 he attended the Bauhaus in Weimar, studying mural painting with Vasily Kandinsky and typography, creating the Universal alphabet, a typeface consisting of only lowercase letters that would become the signature font of the Bauhaus. Bayer returned to the Bauhaus from 1925 to 1928 (moving in 1926 to Dessau, its second location), working as a teacher of advertising, design, and typography, integrating photographs into graphic compositions.

He began making his own photographs in 1928, after leaving the Bauhaus; however, in his years as a teacher the school was a fertile ground for the New Vision photography passionately promoted by his close colleague László Moholy-Nagy, Moholy-Nagy’s students, and his Bauhaus publication Malerei, Photographie, Film (Painting, photography, film). Most of Bayer’s photographs come from the decade 1928-38, when he was based in Berlin working as a commercial artist. They represent his broad approach to art, including graphic views of architecture and carefully crafted montages.

In 1938 Bayer emigrated to the United States with an invitation from Alfred H. Barr, Jr., founding director of The Museum of Modern Art, to apply his theories of display to the installation of the exhibition Bauhaus: 1919-28 (1938) at MoMA. Bayer developed this role through close collaboration with Edward Steichen, head of the young Department of Photography, designing the show Road to Victory (1942), which would set the course for Steichen’s influential approach to photography exhibition. Bayer remained in America working as a graphic designer for the remainder of his career.

Introduction by Mitra Abbaspour, Associate Curator, Department of Photography, 2014 on the MoMA website [Online] Cited 01/10/2021.

Herbert Bayer (American born Austria, 1900-1985)

Self portrait

1932

Photomontage

Gelatin silver paper

35.3 x 27.9cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder, München

© 2015, ProLitteris, Zurich

Genia Rubin (Russian, 1906-2001)

Lisa Fonssagrives. Robe: Alix (Madame Grès)

1937

Gelatin silver paper

30.3 x 21.5cm

Foto: Christian P. Schmieder / Sammlung Siegert, München

© Sheherazade Ter-Abramoff, Paris

Genia Rubin (Russian, 1906-2001)

Genia Rubin (actually Jewgeni Germanowitsch Rubin, 1906-2001) was a Russian fashion and portrait photographer and painter .

Rubin left Russia in 1927 and initially assisted the cameraman Karl Freund in Berlin. He then studied photography at AGFA IG Farben. In 1929 Rubin went to Paris, where he worked as a still photographer in the Pathé film studios and as a portrait photographer. In 1931 he returned to Berlin, met the photographer Rolf Mahrenholz and opened his own photo studio on Berlin’s splendid boulevard, the Kurfürstendamm. It was soon discovered and launched by Franz Wolfgang Koebner, editor-in-chief of the popular magazines Das Magazin and Elegante Welt. In 1935 Rubin moved back to Paris, where he met Harry Ossip Meerson; after his departure for America Meerrson took over his studio. During this time Rubin photographed fashion for “Femina”, Harper’s Bazaar and Australian “The Home”. After the war he met the English court photographer Baron (Stirling Henry Nahum); until 1956 he worked alternately as a “fashion guest photographer” in “Baron’s Studios” in London and as a Parisian photo correspondent for the Daily Express.

Rubin had started to paint in Paris at this time. Through his acquaintance with André Breton, for example, he came into contact with contemporary painting in Paris and was among other things. In 1947 he took part in the international surrealist exhibition at the Maeght Gallery .

In 1957 Rubin stopped photographing fashion and took pictures of parks, gardens, palaces and art objects in France, England and Italy for “Maison et Jardin” (“House and Garden”, Condé-Nast ). From 1959 he devoted himself again to modern painting, also as a collector.

Text translated from the German Wikipedia website

Atelier Manassé

Mein Vogerl / My bird

c. 1928

Gelatin silver print

Foto: © IMAGNO/Austrian Archives

Studio Manasse

“… Olga Solarics (1896-1969) and her husband Adorjan von Wlassics (1893-1946) ran the Manasse’ Foto-Salon in Vienna from 1922-1938. Olga seems to have been the one interested in the photographic nude. She (or they) exhibited at the 1st International Salon of Nude Photography in Paris in 1933…”

“… Studio Manasse, which flourished in the 1930s in Vienna, captured more than just portrait photography bursting with erotic charge; it immortalised the fluid state of beauty and the ‘new woman’: confident in her own sexuality as she struggled to redefine her position in the modern world. Each picture offers a conflict of concepts, as provocative poses are presented in such traditional roles that the cynicism intended renders them humorously absurd. Adorjan and Olga Wlassics, a husband-and-wife team, founded Studio Manasse in the early 1920s. The first Manasse illustrations appeared in magazines in 1924, a booming industry at the time, as the movie industry skyrocketed and publications aimed to satisfy a public obsessed with glimpses into the world of glamour. Attracting some of the leading ladies of the time from film, theatre, opera, and vaudeville, Studio Manasse created masterpieces, employing all the techniques of makeup, retouching, and overpainting to keep their subjects happy while upholding an uncompromised artistic vision. Moulded bodies were dreams with alabaster or marble-like skin; backgrounds were staged so that the photographer could control each environment. And as their art found a home, the Wlassics found themselves able to afford a style of life similar to those reflected in their photographs. Their clients ran the gamut, from the advertising agencies to private buyers. When the Wlassics opened a new studio in Berlin, their business in Vienna was managed more and more by associates, until 1937, when the firm’s name was sold to another photographer. Adorjan passed away just 10 years later; Olga remarried and died in 1969… ”

Text from the Historical Ziegfeld Group website Nd [Online] Cited 20/06/2016, No longer available online

Zentrum Architektur Zürich ZAZ Bellerive

Höschgasse 3, CH-8008 Zürich

Phone: 044 545 80 01

Opening hours:

Wednesday – Sunday 2pm – 6pm

Closed Monday and Tuesday

You must be logged in to post a comment.